Support’s first operational feature is its proximity. No support can take place outside a close encounter, getting entangled in a situation and becoming implicated in it. A desire emerges, an offer opens … it is not a word but a call, a longing; it cannot rely on intellectual awareness or abstract information, but requires a proximity and intimacy.

—Céline Condorelli, Gavin Wade, and James Langdon1

In response to the worldwide economic recession of 2008, the housing cooperative La Borda was born from the desire of a community of people to create a dignified living environment. The specific conditions of the real estate bubble that burst in Spain was created by more than a decade of rising house prices and by families across the country taking on growing levels of debt. The beginnings of this situation can be traced back to the death of Franco in 1975, when the establishment of a democratic state and the approval of the new constitution in 1978 triggered a period of economic growth. Culminating in the late 1990s under the government of Jose María Aznar, deregulation and privatization policies led to a major construction boom by private developers and the promotion of home ownership over rental housing by public administrations. As debt became the new norm and the crisis struck, many defaulted on their mortgages and were forcibly evicted, resulting in a severe housing crisis.2 Within this context, different groups of activists emerged and organized around the struggle for housing as a human right. The most well-known manifestation of this is the Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (Platform for People Affected by Mortgages, or PAH), which has been working for over a decade to stop and transform the legal frameworks for foreclosure and evictions.

It is not easy to define the precise contours of how the complex, emancipatory process that underpins La Borda started. But what can be said is that it emerged from a series of informal encounters in 2011 and 2012 between members of the architecture cooperative Lacol, the labor cooperative La Ciutat Invisible, the association Sostre Cívic, and other associationist movements in the area of Sants, a working-class neighborhood of Barcelona with a long tradition of cooperatives. The collective of collectives that became La Borda drew from the neighborhood’s heritage of popular self-organization and autonomy and from its worker and farming co-ops, co-op schools, and service-based co-ops, among others. Over the next two years, there were many assemblies, workshops, and innovative proposals for how to subvert the conventional property ownership system that dominates access to housing in Spain. In 2014, La Borda was officially founded as a housing cooperative, and, in November 2015, they successfully obtained a seventy-five-year leasehold from the Barcelona City Council for a plot of land classified as state-subsidized housing (HPO).

The year 2015 was a turning point in the politics of the city when Barcelona en Comú (Catalan for “Barcelona in Common”), a new leftist political party won city council elections, and Ada Colau, the former spokeswoman of the PAH, was elected mayor. Many of Barcelona en Comú’s founding members were active participants in social and political movements, including the PAH and the anti-austerity Indignados 15M movement, among others. Thus, there was great interest in supporting social and cooperative housing initiatives from the very beginning. The seventy-five-year leasehold for state-subsidized housing that La Borda obtained from the Barcelona City Council that year was the first time such an arrangement had ever been established with the city. Considering Spain’s history of public policies favoring privatization and the indebtedness that resulted, the subversive power of such an initiative immediately provoked further interest in Barcelona and beyond. Many newspapers and news platforms reported on this economic model of leaseholds, which was already popular in other countries (like Ándel in Denmark or FUCVAM in Uruguay). In Spain, it has since been replicated in various other cities.

La Borda is the result of a series of assemblies in which various working groups, including ones focused on cohabitation, legal policies, solidarity economies, communication, design and architecture, and internal management, focused on elaborating—separately first, and then jointly—different elements of the housing cooperative. The project is grounded in a form of collective ownership that avoids the possibility of speculation. But this was only possible by collaborating with financial entities that share the same values and ethics. Learning from and working with the cooperative bank Coop57, as well as La Dinamo foundation, the group experimented with novel financing and economic models including microcredits, grants, housing loans, and participatory loans. This was necessary to allow future residents to pay their share and become part of the cooperative within the context of a financial crisis and economic austerity.3

La Borda did not merely seek to rethink the financial politics of housing. As the overall process of design (architectural, but also of the ethics and protocols of conviviality) was based on assemblies and communal decision-making processes, the cooperative knew who was going to live in La Borda long before construction started. This allowed the architects to respond directly to their needs, one of which derived from the fact that most future residents did not have a car and preferred to use bicycles to get around. Existing parking regulations and other related land use policies, however, were designed for the standard imaginary of a citizen who owns a car, and were therefore inapplicable or unnecessary for residents of La Borda. Instead of complying with these unnecessary regulations, the collective successfully made the case that these regulations should not only not apply to them, but also that they needed to be changed more widely. New municipal legislation was approved in 2017 that significantly reduced the required number of spaces in underground car parks in new buildings. While the Superior Court of Justice of Catalonia (TSJC) unfortunately rescinded this regulation in 2021, many similar ideas promoted in La Borda are aligned with new City Council policies regarding mobility and the use of public space, like the municipality’s Superblock project.4

According to Lynn Segal, “As the world becomes an ever lonelier place, it is sustaining relationships, in whatever form they take, which must become ever more important. An act of defiance, even.”5 The political agency of architecture can thus be narrowed down to the scale of the building itself, with the relationships that have been built over the past ten years inside and around La Borda representing a powerful act of resistance.6 Opened in fall 2018, La Borda is a project built not only of wood and glass, but also by care and affect. Spaces of conviviality and interdependence in this twenty-eight-unit housing project include a common laundry and kitchen, which are not just spaces of encounter for residents, but also where they share household appliances and materials, as well as organize the maintenance and cleaning of the building and its facilities.7 There is also a common cupboard on each floor with shared tools and cleaning appliances, which helps avoid overfilling individual smaller units.

The building comprises apartments of three different sizes (forty, sixty, and seventy-five square meters) as a way to promote diversity and respond to different needs. This is particularly important given the fact that the concept of the traditional nuclear family leaves aside other structures of kinship and coexistence that are becoming increasingly common and urgent. As a result, the group of residents is heterogeneous, from young couples and seniors living alone to a few families with young kids. The motto of La Borda is “we build housing to build community.” By taking care of each other, residents constantly cultivate an ethics of solidarity and interdependence. People cook for each other. Elderly residents take care of kids to allow their families to go shopping.

Conversations on balconies respecting social distance. Courtesy of La Borda.

La Borda common kitchen put to use during Covid-19. Photo Álvaro Valdecantos.

Young resident skating in the building during lockdown. Courtesy of La Borda.

Conversations on balconies respecting social distance. Courtesy of La Borda.

Covid-19 challenged the politics of affect and principles of care. For La Borda, however, it was a perfect testing ground for all the theories that went into the project and community since its inception. The building’s main communal spaces—the kitchen and dining room, the laundry, and the open roof—were scarcely used in the first year after people moved in. This was in part due to the fact that they were the last to be finished. But it was also because they were built collectively, as a process through which residents got to know each other and discover what it meant to create communal space. When social distance and other pandemic-related health measures were implemented, neighbors used these spaces to support one another. Daycare was collectivized, for instance, whereby small groups of adults took turns taking care of children and allowing their families to spend a few hours working from home. Residents also organized in small groups to cook for everyone, thus minimizing the number of people who would need to go grocery shopping and reducing the risk of contagion.

Cristina Gamboa, a member of Lacol and resident of La Borda, explains that, today, the common kitchen is still being used following the practice started in 2020 when a group of four residents cooked for everyone else. These weekly dinners are open for all who sign up in advance, which allows the group to organize the tasks of shopping, cooking, and cleaning. Weekly cooking shifts also implicate and expose the residents to political issues such as gender roles, family structures, and notions of hospitality. Despite their efforts, however, Gamboa explains that the tapestry of voices inhabiting La Borda is not as diverse as they would like. The educational level of the residents, their leftist ideas, and their interest and active participation in political struggles—such as access to housing—gives the group a certain homogeneity. By living together, solidarity emerges, and a feeling of belonging becomes stronger. For this reason, it is important to remain aware that things can still be improved, and everyone must keep working together to shape the future they long for and have not yet experienced.

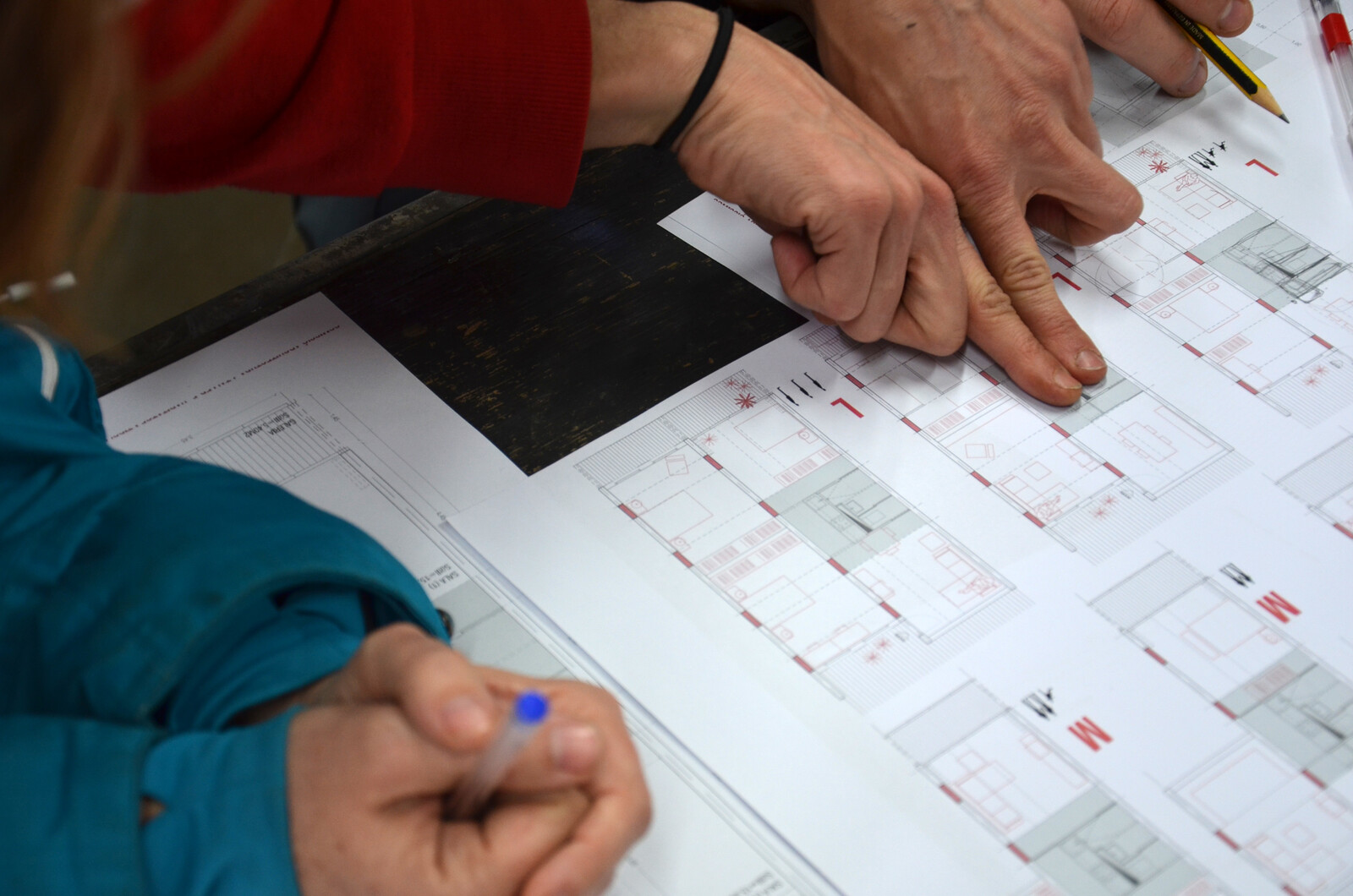

Participative workshops done by Lacol for the design of La Borda. Courtesy of La Borda.

Participative workshops done by Lacol for the design of La Borda. Courtesy of La Borda.

Participative workshops done by Lacol for the design of La Borda. Courtesy of La Borda.

Participative workshops done by Lacol for the design of La Borda. Courtesy of La Borda.

As these past years have shown, in moments of vulnerability, gatherings are spaces to share not only fears and fragility, but also hopes and possibilities. The bonds created there can teach us that what connects us is more powerful than what divides us. Because as Donna Haraway puts it, “it matters what relations relate relations. It matters what worlds world worlds.”8 The collective construction of the city by citizens that starts from the relations with our own neighbors can be a catalyst for living otherwise. It can be the support structure needed to create, inhabit, and share worlds that don’t deny vulnerability, but rather embrace it as just another component of our daily life. And with that embrace, these worlds might allow us to create—and become part of—a community that will change and hold us accountable.

Céline Condorelli, Gavin Wade, and James Langdon, Support Structures (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2009).

Ethel Baraona Pohl, “Cooperative housing as a means more than an end,” in Together! The New Architecture of the Collective, eds. Ilka Ruby, Andreas Ruby, Mateo Kries, Mathias Müller, and Daniel Niggli (Berlin: Ruby Press, 2017).

See ➝.

Lynne Segal, Radical Happiness: Moments of Collective Joy (London and New York: Verso, 2018).

Segal, Radical Happiness.

The Care Collective, The Care Manifesto: The Politics of Interdependence (New York and London: Verso, 2020).

Donna Haraway, “Receiving Three Mochilas in Colombia: Carrier Bags for Staying with the Trouble Together,” in Ursula K. Le Guin, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (London: Ignota, 2019).

In Common is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, the Chicago Architecture Biennial, UIC College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts, and arc en rêve within the context of its exhibition “common, community driven architecture.”