How do you make a home in the context of displacement? What is a home in a country marked by high levels of urban violence? How is a sense of belonging maintained in the face of being confronted as “other” and “out of place”? For migrants and refugees, home is often a series of places, including those left behind, present-day temporary accommodation, and a hoped-for destination, which might also be a return. For Sara Ahmed, in the context of displacement, home is “often that which exists in the failure of memory.” When an individual sense of home is lost and no longer exists, it is at times replaced by a collective sense of place.1 Making home is a practice of creating a common space with the presence of many other pasts. Home is always both present and distant; a difficult and contested terrain that must be worked towards and maintained.

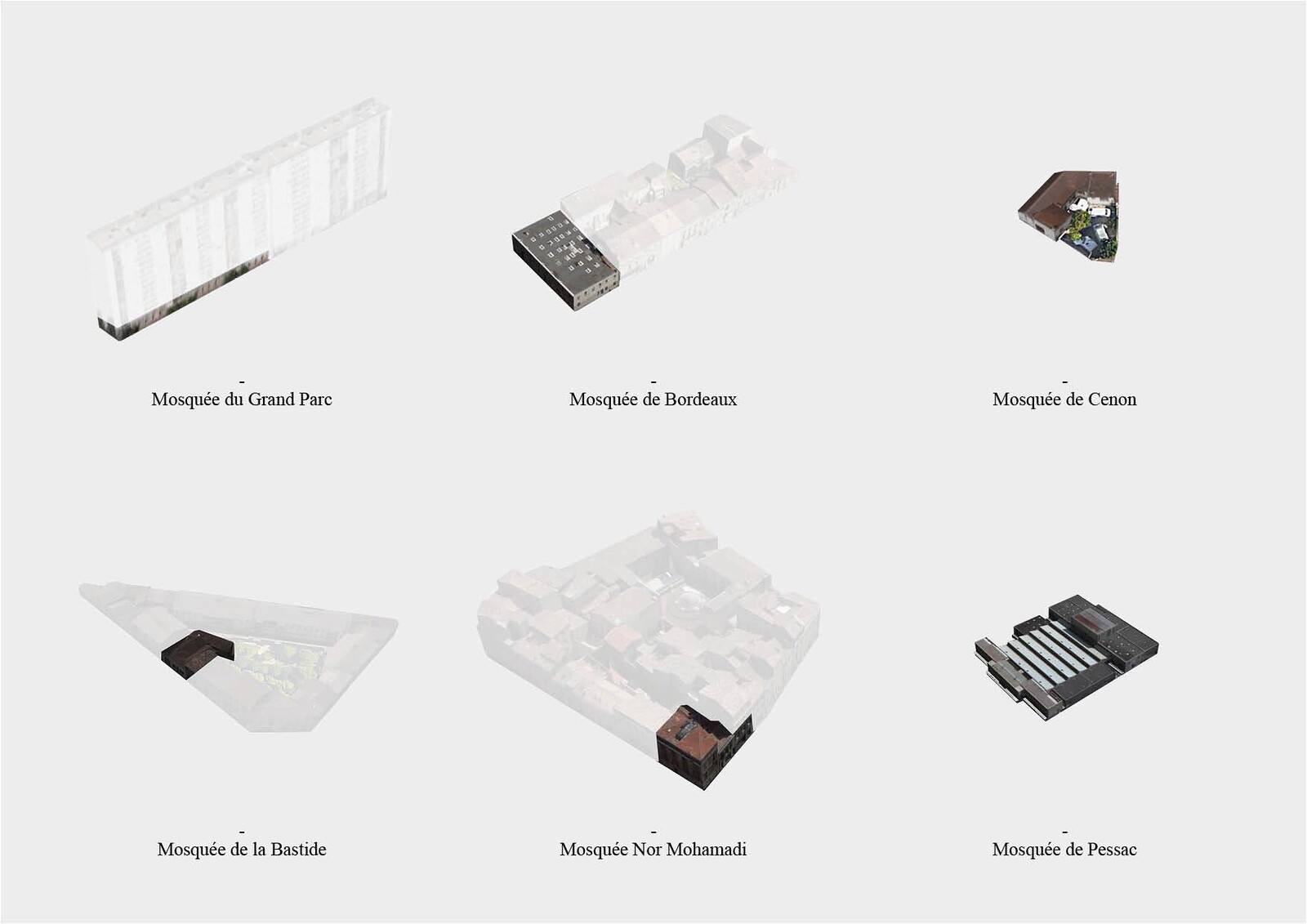

For East African refugees in Cape Town, the “Somali mall” often acts as a form of home. These multi-story sites include shops, residential accommodations, and services, all acting as a social and physical infrastructure for new arrivals, and as a place to meet for those already living within the city. They are also intimately connected to similar sites elsewhere, creating a dispersed geographic intimacy across cities from Nairobi to Lusaka, to Cape Town, and Minneapolis.2 Shops in Somali malls draw distant sites into relation. They become homes in contexts of displacement, sites of precarious possibility.

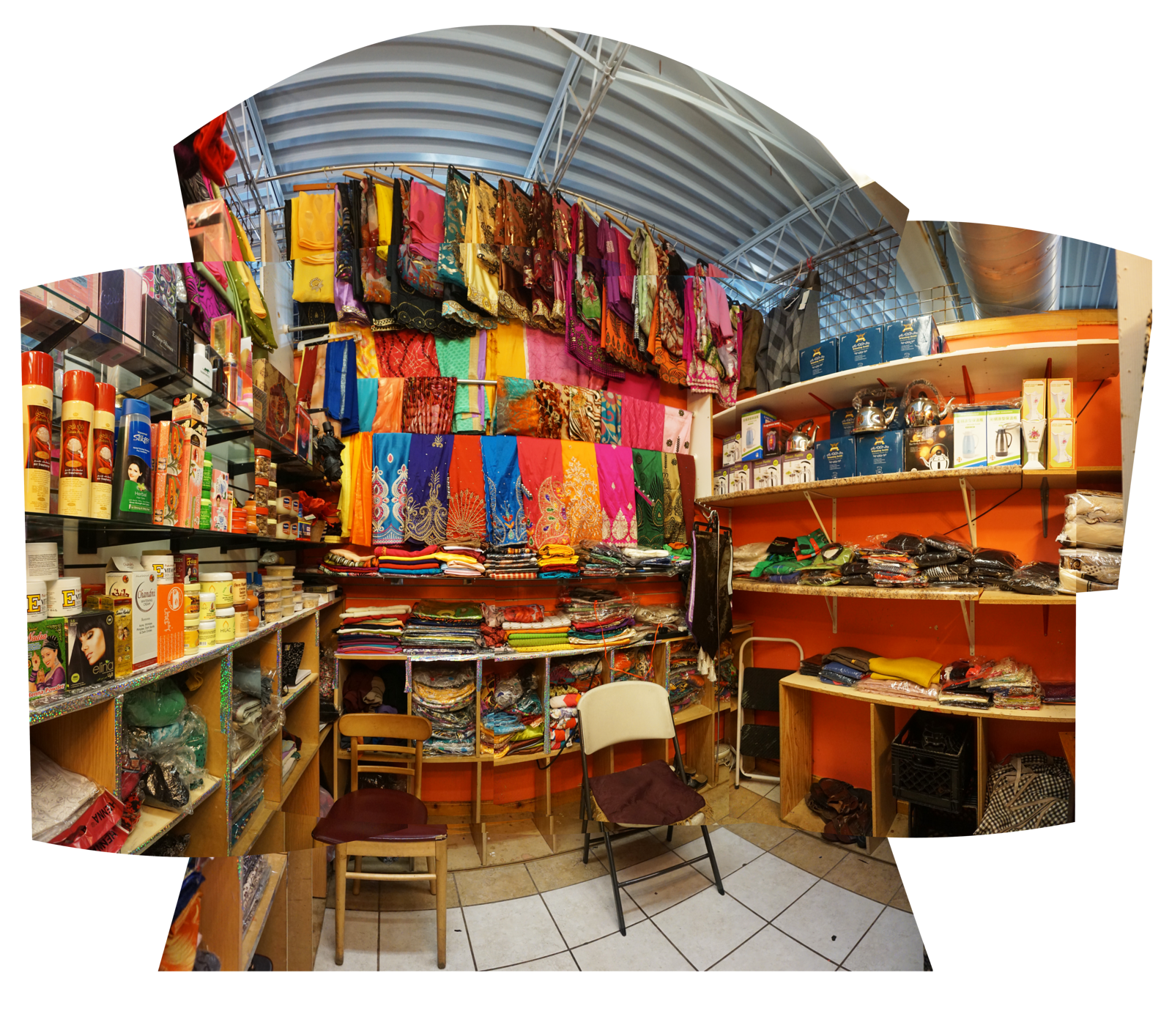

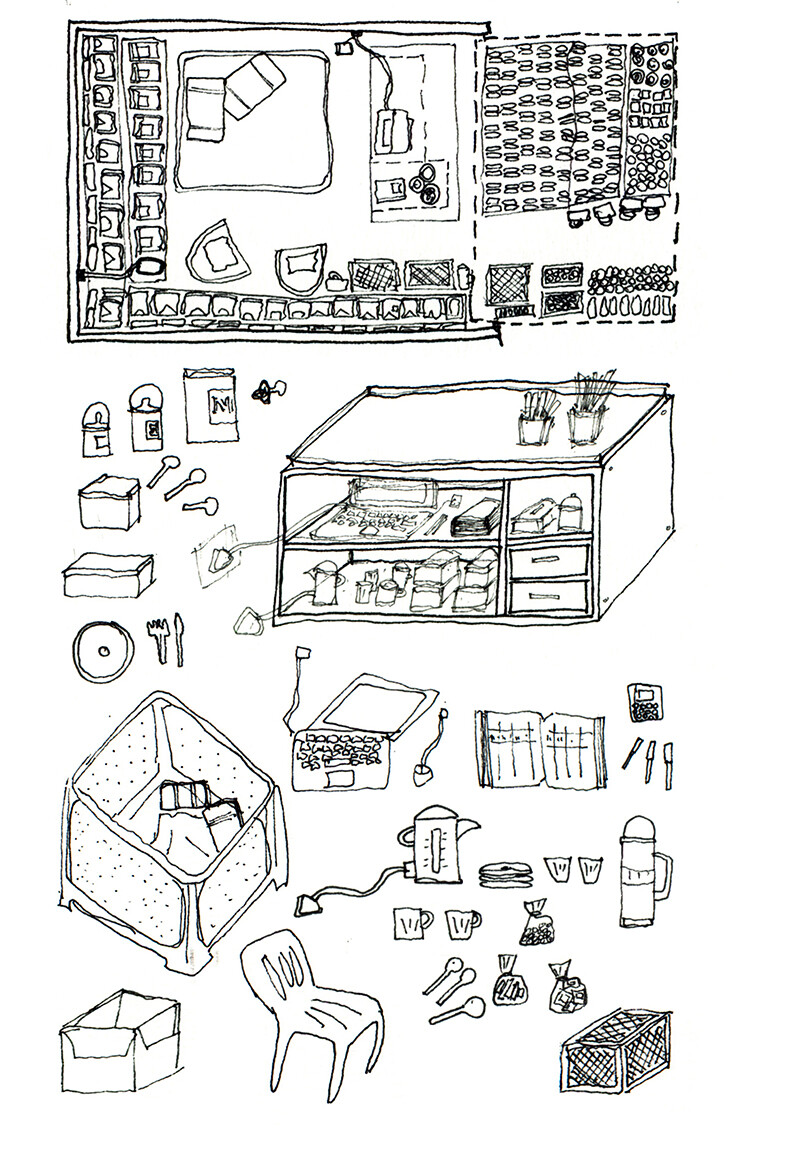

Fatima’s Shop, Bellstat Junction, Cape Town. Drawing by Huda Tayob, 2014-2015.

Fatima’s shop, Cape Town

Fatima’s shop is a small clothing store that she opened in 2010 in Bellville, a northern suburb of Cape Town that is increasingly known for its growing pan-African population.3 Fatima fled to South Africa from Somalia as a refugee in 1997. Her small shop is within Bellstat Junction, one of numerous Somali malls in the area. It is only around two and half square meters in size, and every interior surface is used to display goods for sale. Shirts, t-shirts, pants, and jeans hang from hooks lining the walls and ceiling, while socks, belts, caps, and leather sandals are laid out on tables and counters. The front of the store leans out into the walkway with a wooden board resting on crates. Here, items described as “Somali food,” including various packets of unlabeled spices, soup stock, and oils, sit among bags of rice, sticks of incense, boxes of sweets, and small bottles of perfume. This makeshift table is a curated display aiming to draw the passer-by in, with careful attention given to its arrangement. At the end of each day, all the goods are brought inside and the steel roller-shutter is drawn down over the front of the store and padlocked to the ground.

Apart from the hooks and storage shelves that line the edges of this small store, there are two larger items of furniture that define the space: a cabinet and a cot. The cabinet, which likely had a former life in someone’s living room, marks the threshold between the interior and exterior and serves as a countertop. It holds Fatima’s accounting book, where she notes all items bought and sold; a tin of money where she keeps small change for customers; a kettle for boiling water; and a thermal flask, along with small packets of cardamom, cinnamon, and cloves to be ground for tea. Inside some drawers there is also food for Fatima’s one-year-old son, as well as packed breakfasts and lunches for herself and her older daughter, who often joins her at the shop after school. At the center of the shop is a cot, where her son sleeps and plays over the course of the day. There are also always several plastic chairs and crates in the vicinity, which are pulled out and rearranged to accommodate visitors who stop by.

Fatima is the main earner for her family. She spends most of her time in this space: at least ten hours most days, seven days a week.4 As she is also her family’s primary caregiver, Fatima’s shop plays an important role in her family life. Her shop is not just a place for her family in Cape Town to gather, however. It is also a place through which she stays connected to extended family—and practices of sociality—in other parts of the world. Many of the goods in the store are sourced through family networks and personal relationships from outside of South Africa, in her case mostly Kenya and Dubai.

Although neither Fatima nor her family sleep in the shop—which is common practice in the area and among refugees in the city—it acts as a kind of home. It is where most daily meals are eaten. When I would visit during fieldwork, Fatima was often cutting meat, vegetables, or onions for her family’s evening meal. One evening, Fatima and the neighboring stall owner prepared food together to send to a new mother who had just given birth. On another, they were making paper decorations for a wedding celebration nearby. Fatima’s days were regularly punctuated by prayer intervals and guests dropping by bringing news, be it of the latest violence in townships, births and deaths among common acquaintances, events in Kenya or Somalia, or the latest update on UN resettlement cases. Most afternoons, Fatima’s older daughter completes her homework between helping customers or running small errands.

These domestic practices within small stores and Somali malls are not unique to Fatima’s shop. Many of the shops in Somali malls are run by women and are central to enabling a sense of being-at-home in the city.5 These “kinds of spaces,” in the way that Mary Douglas describes home, are characterized by the regularity of peoples, spatial practices, and things; of social visits, feeding children, preparing food, and doing homework, activities that might be assumed to take place behind the closed doors of a family home.6

While there is a sense of domesticity in these shops that is at once intimate and immediate, they are also part of wider social networks and gendered inhabitations of publicness. When passing by, there is always a crate, a box, or a plastic chair at hand to draw near for a quick (or long) visit, along with an invitation to join for tea. Sometimes there is a flask with tea from home, along with a few cups for visitors. But if not, there is always a tea or coffee shop nearby where an order could be placed, or a group of roving tea traders with flasks of black or milk tea. Drinking tea within the shop emphasizes the gendered nature of the markets and these small shops, as the numerous coffee shops within Somali malls were largely male spaces.

Fatima’s shop is like many other spaces in the area, yet one that I became particularly familiar with over the course of 2014–2015. I spent many hours in this small stall talking to her and drinking tea with her friends and family. Her shop is central to her ability to create a sense of domesticity in Cape Town and a place where she can provide for her family and friends. The shop is a space through which she reconstructs a displaced domesticity, which involves preparing food, cooking, socializing, and caring, out of the series of homes lost on her journey to South Africa, all in this small space within a Somali mall.

Fatima’s shop sits within one of the many new Somali malls that have been established in Bellville since the early 2000s.7 The particular building where Fatima’s shop is located, Bellstat Junction, is one of the few that was renovated specifically for its purpose. Until 2008, the building was a large, run-down warehouse that had been subdivided for multiple traders. Following an increase in xenophobic violence, however, growing demand for shop space led to the building’s renovation in 2009, in what can be described as a practice of slow, quiet, and small additions that accumulated into a larger change within the area.8 The renovation created a series of small shed-like stores structured by a walkway, with single story stalls in the middle and double story shops around the outer edge. Fatima’s stall is one of the single-story spaces that opens onto this walkway.

The shop’s heavy metal door and padlocks are a direct response to memories of violence both within and beyond South Africa’s borders. Fatima had moved to Bellville to live and work after a series of violent experiences in other parts of the Cape Peninsula, in Worcester, Khayelitsha, and Hannover Park. Her shop, as a space for being-at-home, is one in a series of sites that Fatima and her family has occupied, following serial displacements in Somalia to refugee camps in Kenya and then to shops and homes around the Cape Peninsula.

Hajra’s shop, Minneapolis

About two years before my research, in 2012, Fatima’s family was officially approved for third-country resettlement in the United States, yet at the time of meeting they were still waiting for confirmation of a relocation date and site. They were hoping for resettlement in Minneapolis, where Fatima’s sister had been relocated several years before. As the site of the largest Somali refugee population in the US since the early 1990s and the onset of civil war in Somalia, Minneapolis was often mentioned as a hoped-for destination of resettlement among people I spoke to in Cape Town. Minneapolis is also home to several well-known Somali malls, including Karmel Souk and Village Mall, which initially started in unused industrial sites in central Minneapolis. Unlike the generic markets in Cape Town, Karmel Souk clearly announces its presence as a Somali mall, with a street-facing mural referencing the East African coast and the Middle East. Karmel has an old and new part to it; the old part was created within an existing mill building and had thirty-five shops when it initially opened in 1998, while the new part was specifically designed for its current purpose.9 Village Mall, or “24” as it is more commonly known due its location on 24th Street, was opened soon after. The shops in 24 occupy a former bakery mill that has been subdivided into small shops, restaurants, and office spaces. In both sites, the majority of shops are run by women.

I travelled to Minneapolis in 2015 and again in 2018 to meet family and friends of contacts in Cape Town. Hajra is Fatima’s cousin and, at the time I met her in 2018, she was running a shop in 24 alongside working as a part-time carer in a retirement home. Hajra had lived in South Africa, in Pretoria and Johannesburg, for fifteen years before being resettled in Minneapolis in 2009. Hajra had a larger store than Fatima’s, about double the size. In addition to the cosmetics and small food items, she also sold carpets, curtains, clothes, and blankets, all of which appeared to be the exact same kinds of goods as those sold in Somali malls in Cape Town. One of the reason for this is that, as in Cape Town, most of Hajra’s items are sourced via cross-border traders, namely women who are known through family networks.10 And Hajra, like many of those running these shops in Minneapolis, previously ran a similar kind of space in South Africa. In many ways, Hajra’s store in Minneapolis was made with the memory and knowledge of her previous stores, with connections across the various markets she has worked in and actively maintained by female cross-border traders.

Household goods, such as curtains, carpets, and food items, point to women as primary home-makers, and these stores serve as both points of recognition for a particular kind of subject-position, and sites of possibility for women to make a home that is familiar beyond the mall itself. These small shops within Somali malls are therefore interiors within a network, or along a trajectory of similar spaces. They are spaces of being-at-home, where the maintenance of transnational networks enables and constitutes a spatial intimacy across sites and geographies. As Cawo Abdi has noted, Somali refugees are actively remaking the idea of “home” in different countries of settlement around the world. While this is shaped by refugee policies, border regulations, and local contexts, it is also importantly shaped by the “imagination” and sense of place that is carried with those who move. As she notes, “how desired destinations are imagined is crucial in how migration is experienced.”11 Somali malls across sites such as Cape Town, Minneapolis, and elsewhere are not only defined by a linear relationship of “fleeing” and “arrival,” but also forms of connection that endure in less tangible ways through desire and a sense of possibility.

What kind of a home is this?

Urban violence in South African cities reflects long histories of racialized violence and displacement and is increasingly mobilized against non-citizens as “foreign others.” This is matched with growing xenophobic sentiment that positions “foreign” Africans as an easy outlet for the failed promises of the new South Africa.12 In 2008, xenophobic violence spread throughout the country; sixty-two people were killed and 150,000 were displaced.13 For both Fatima and Hajra, 2008 was a moment of violent displacement along a longer trajectory. Fatima and her family were displaced from their home in Khayelitsha at the time, spending several weeks at a temporary refugee camp, and later moving to stay and work in Bellville. Both Hajra’s shop and home in Pretoria were attacked, which led to her family’s resettlement in the US the following year. The expansion and growth of Bellstat Junction, along with other Somali malls in the area from 2009, was in many ways a response to the 2008 violence.

2008 was also the year that the High Court of South Africa granted an eviction order in what has since been described as the largest judicially sanctioned post-Apartheid eviction process. On March 10, 2008, all inhabitants of the informal settlement Joe Slovo were ordered to be removed to make way for a new housing project, the N2 Gateway Housing. Despite the fact that the N2 Gateway Housing project has largely been seen as a vanity project meant to hide Cape Town’s poverty from visitors traveling into the city along the N2, the freeway that runs from Cape Town International Airport to the city, the ruling was upheld on June 10, 2009 by the Constitutional Court.14 This resulted in the displacement of 20,000 residents to what was termed a “Temporary Relocation Area,” known locally as Blikkiesdorp, an area thirty kilometers outside of the city that mirrors Apartheid planning, revealing of a myriad of failed promises.

To make and maintain home in the context of South African cities requires a reading across registers and sites. Present histories of violence and racialized inequality persist and are reworked to continue disenfranchising vulnerable populations, citizen and non-citizen alike. For multiple generations of forcibly displaced people, home is often experienced as a trajectory of spaces, as sites of possibility and precarity. As Asef Bayat recognizes, an informal life is also often an insecure life.15 Returning to 2008, as a time of multiple violent displacements, is a reminder to work against the reproduction of enclosure, and towards other possible guides for the imagination.16

In Cape Town, histories of forced racial disenfranchisement and displacement map onto developer-led inequalities and coincide with new forms of racialized exclusions. For many, home is often a practice of quietly making and claiming a place in the city, as well as an active struggle for belonging. This “quiet encroachment” might not be an overt form of resistance, yet is vital to forming livelihoods and finding ways of living in urban areas with limited resources.17 Acts of gathering together make home, and often coincide with small additions, extensions, and adjustments to the built environment. Paying attention to these quiet practices that often take place within the unfolding and overlapping of violence and precarity draws out other ways knowing, doing, and existing in the city.18

Sara Ahmed, “Home and Away: Narratives of Migration and Estrangement,” International Journal of Cultural Studies 2, no. 329 (1999): 341.

Huda Tayob, “Transnational Practices of Care and Refusal,” Coloniality of Infrastructure (e-flux Architecture, 2021), ➝.

Part of this essay will be published in Huda Tayob, “Transnational Home-making in Somali Malls: Cape Town and Minneapolis,” in The Urban Refugee, eds. Kivanç Kilinç and Bulent Batuman, (Bristol: Intellect Press, 2023). The drawings have previously been published in Huda Tayob, “Can Drawing ‘Tell’ a Different Story?,” Architecture and Culture 6, no. 1 (2018): 203–222; and Huda Tayob, “Drawing out Home-Making,” in Architecture and Feminisms, eds. Helene Frichot, Catharina Gabrielsson, and Helen Runting (London: Routledge Critique Series in Architectural Humanities), 265-269.

As I’ve written elsewhere, drawing is a means of drawing out and paying attention to these small spaces where the abundance of detail is apparent all at once. See Huda Tayob, “Opaque Infrastructures: Black Markets as Architectures of Care,” Public Culture 34, no. 3 (2022): 375-384.

Ahmed, “Home and Away,” 341.

Mary Douglas, “The Idea of a Home: A Kind of Space,” Social Research 58, no. 1 (1991): 287-307.

Tayob, “Transnational Practices of Care and Refusal.”

Asef Bayat, Life as Politics: How Ordinary People Change the Middle East (Redwood City: Stanford University Press), 57.

I have since heard that Old Karmel was demolished and a new structure is being built on the same site.

Interview with Hajra (Minneapolis, 2018); interview with Sara (Cape Town, 2016); interview with Abida (Minneapolis, 2018). See also where I have written about cross-border traders as an infrastructural system and cross-border trading networks among Somali malls, Huda Tayob, “Architecture-by-migrants: The Porous Architectures of Bellville,” Anthropology Southern Africa 42, no. 1 (2019): 46- 58.

Cawo Mohamed Abdi, Elusive Jannah: The Somali Diaspora and a Borderless Muslim Identity (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 8.

Jean Pierre Misago and Loren Landau, “Running Them out of Time: Xenophobia, Violence and co-Authoring Spatiotemporal Exclusion in South Africa,” Geopolitics 28, no. 4 (2022).

Tayob, “Transnational Practices of Care and Refusal.”

Lilian Chenwi and Kate Tissington, “’Sacrificial lambs’ in the quest to eradicate informal settlements: The plight of Joe Slovo residents: Case Review,” Sabinet 10, no. 3 (2009).

Bayat, Life as Politics, 60.

Bayat, Life as Politics, 94.

Asef Bayat’s concept of “quiet encroachment” recognizes the importance of everyday and ordinary practices. Bayat, Life as Politics, 57.

Denise Ferreira da Silva, “Toward a Black Feminist Poethic” The Black Scholar 44, no. 2 (2014): 81-97.

In Common is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, the Chicago Architecture Biennial, UIC College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts, and arc en rêve within the context of its exhibition “common, community driven architecture.”