There are three broad structural conditions that bind architects―no matter their philosophical, discursive, or formal affinities―to an increasingly untenable status quo. First is the discipline’s centuries-long cultivation of spatial concepts and organizational principles, at both the architectural and urban scale, that give form to an energy-intensive society. Second is the powerful economic engines that drive the production of built form, enable gentrification and wealth accumulation, and prove that the economy of capitalist development is incapable of producing an equitable and sustainable built environment. And third is the existing mode of architectural practice that harnesses architectural labor towards the production of a built environment that in itself is an obstacle to change.

These problems build on each other, and at the center of them lies the design of the built environment—not only its material artifacts but also its infrastructures, economies, ideologies, and cultures of space. What is required to address these issues is nothing less than a general reorientation and reorganization of social space, away from extractive economies and industrial production, and towards maintenance, stewardship, repair, and care.

This need for reorganization brings up many pressing questions. Who will reorganize? And how can existing social structures be overturned without creating serious and perilous issues around power and equality? New forms of cooperation and labor must emerge in order to deindustrialize, reduce our dependence on global supply chains, and address climate change. The question for architecture will be whether design and spatial planning can support or catalyze these changes.

In this context, alternative land ownership models offer a counterposition to real estate development while creating different points of departure for the formulation of architectural ideas. For example, Community Land Trusts (CLTs) are non-profit democratic institutions that deploy communal land ownership as a strategy for creating affordability. While many CLTs focus exclusively on financial and legal mechanisms, surprising spatial and architectural potentials may emerge should a CLT venture beyond their typical operations. This text envisions a scenario in which a CLT introduces a series of resident-based cooperatives in order to transform how land is occupied and forge new relationships between urban and community systems. In so doing, the CLT serves as an instrument for rewriting the terms of engagement between land and people.

CLTs, however, are not “design projects” in the conventional sense; they are community-driven projects that necessarily eschew top-down development. Nevertheless, through their land-based operations, they could open up unexpected terrain where architecture might participate in transformations of social and spatial form, not by offering design solutions, but by offering alternative models—for land use, for stewardship of the built environment, and for cohabitation—that are meant to be appropriated and deployed by the community itself. In this context, architects might recognize that newly proposed configurations of space and form are not a static end, but rather a platform rife with potential.

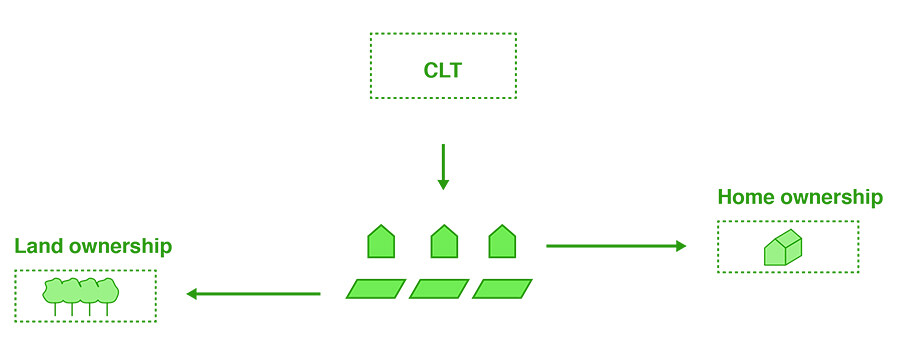

Community Land Trusts create affordability by separating the ownership of land and buildings.

What is a community land trust?

A Community Land Trust (CLT) is a land-owning non-profit organization that offers affordable housing by making an important innovation in the juridical and financial mechanisms of ownership: land held by the organization is held in a trust, and therefore taken off the market, while individual buildings on the land are left available for private ownership. By separating ownership in this way, CLTs decrease the cost of the building and create a guaranteed measure of affordability. In addition, CLTs can adjust the terms of building ownership on their land, such as by placing caps on value appreciation to further protect affordability.

CLTs are also characterized by their democratic governance structures. While they vary a great deal relative to local social and economic conditions, a typical CLT is run by a board that consists of local leaders and residents, becoming an important platform for local governance and self-determination within the community.

These organizations are grassroots, local, heterogeneous, and somewhat rare. They are considered resource-poor and do not conform to our conventional notions of wealth, given that they permanently remove land from the market and intentionally keep home prices low. As nonprofits, they present few, if any, avenues for wealth and accumulation. They are not scalable or easy to run and, as such, are rarely seen as the seeds of paradigmatic change.

Nevertheless, CLTs’ capacity to decommodify land offers the opportunity to see land as something other than property, and to make connections between people and places that are otherwise kept apart by the logic of private ownership. If a CLT were to introduce circuits of cooperative labor to steward the built and natural environment, it could become the core of a new ecosystem of neighborhood cooperation that posits a way of building guided by reformed priorities regarding land, labor, the dissemination of knowledge, and urban form.1

Urban Form

The parcellation of land is an act of abstraction in the service of commodification. Under this logic, land becomes an exchangeable unit to be bought, sold, and traded, severing the rhythms of dwelling from the larger flows of energy and resources that sustain life. Parcellation alienates society from nature while allowing separation and subdivision to become the primary spatial drivers of contemporary civilizational form.

In addition to being parceled, land is further divided into two distinct categories: public and private. Private land is managed and maintained by individuals, families (primarily nuclear), or corporate entities, while public land is managed by municipalities, states, and federal agencies. This division of maintenance is both a social structure and a spatial form: public and private sectors are divided into separate realms and must have a spatially defined jurisdiction where its logic applies. In this way, the city exhibits an unevenness of care, with many urban sites too small for the municipality’s attention and too large for individuals to tend. Latent within the CLT is the potential to operate both within and against these logics.

A CLT is not only a mechanism for parsing ownership of land and buildings, it is also a proposal for rewriting the relationship between land and people. As such, a CLT possesses an untapped potential to subvert the logic of parcellation, both spatially and politically.

San Ysidro, California is an appropriate site for exploring such ideas due to a series of local spatial conditions. First, maintaining large lots is an ongoing issue in the neighborhood, where low-incomes and long workdays prevent individuals from taking on the required labor. These maintenance problems extend to many public areas, where limited public investment has led to large tracts of bare earth and substantial areas of unpaved and underplanted land in the neighborhood. While technically public, this land has nonetheless fallen into the gap between public and private realms, for neither are able to take on the burden of maintenance. These issues will be further exacerbated by climate change, for the low-income residents of San Ysidro will be particularly vulnerable to its effects, not only in the form of fires and extreme weather but also through likely disruptions to global supply chains.

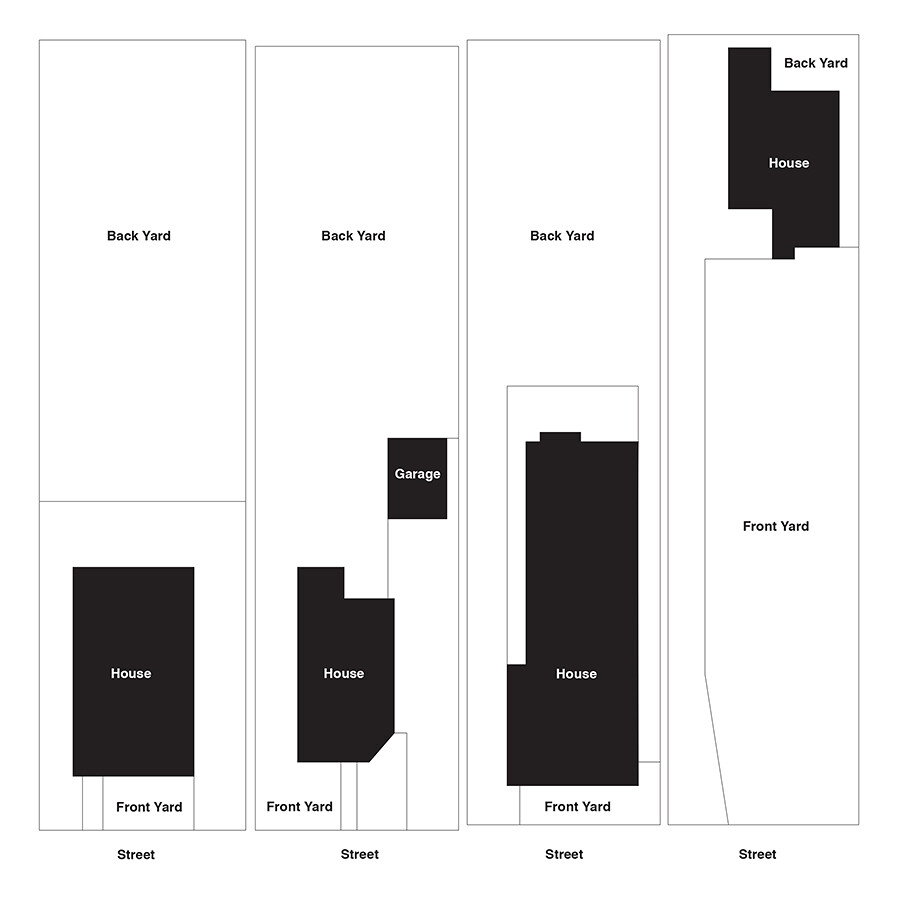

Large lots and single-family homes define the dominant spatial condition of San Ysidro.

In terms of its spatial structure, the neighborhood of San Ysidro is mostly gridded, characterized by a mix of single-family and multi-family dwellings. Individual parcels are large and spacious enough for free-standing accessory units. Building new accessory units would increase density—a change urgently needed, given San Diego county’s characteristic urban sprawl—and do so without demolishing existing homes. This construction itself could also be facilitated by the CLT, granting residents an unusual measure of control over material and labor conditions on building sites. Furthermore, if a CLT owns two adjacent parcels, it can request a lot consolidation from the city, which would trigger different zoning entitlements and allow for higher density on the consolidated lot. A building might thus straddle what was once a property line, defying the inherited system of property.

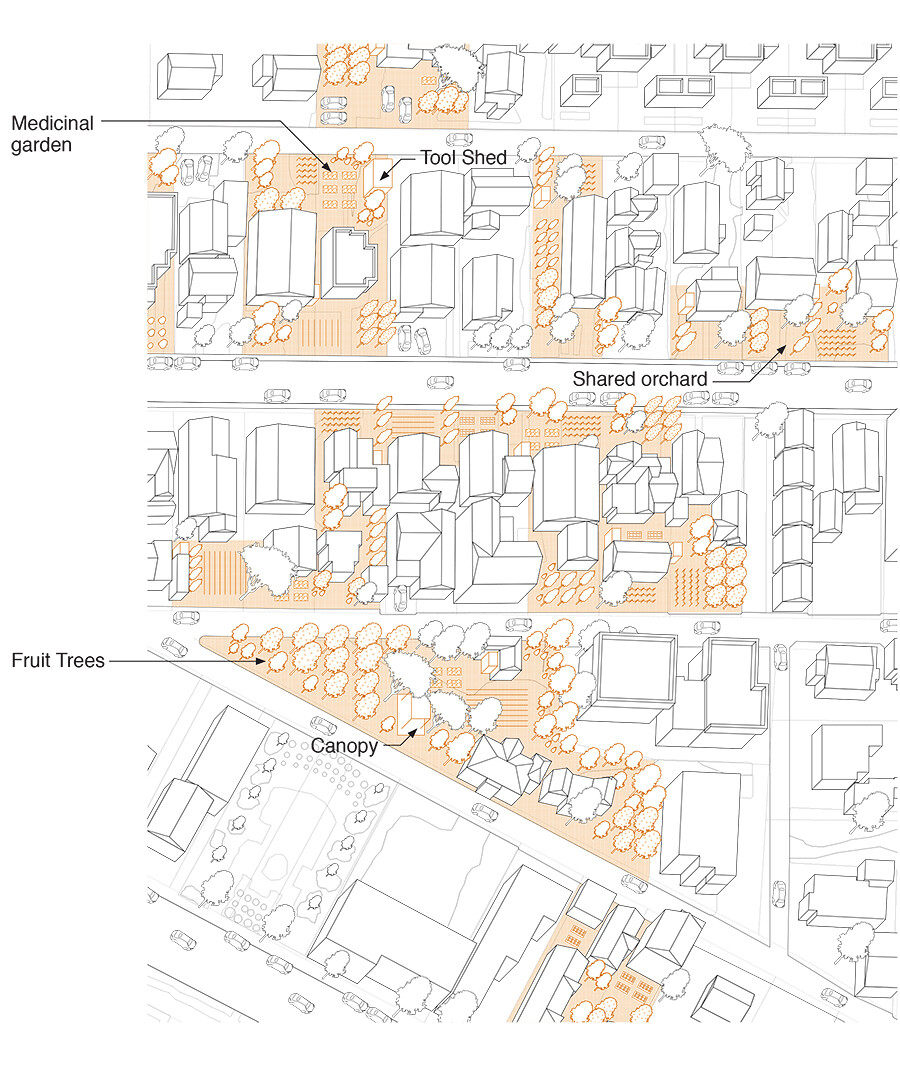

In addition to strategies for densification, a CLT can offer an integrated plan for land stewardship that defies the current division of maintenance stemming from the practice of parcellation. It is not uncommon for CLTs to manage pooled resources to ensure that all members have access to a system of support. For example, CLTs may manage maintenance funds that, when needed, can provide grants to residents for major renovation projects, such as roof replacement. Read spatially, the CLT has the capacity to operate within and across property boundaries, redistributing the burden of maintenance and enabling grander ambitions for land stewardship that would otherwise be inaccessible to individual homeowners due to the high cost of labor and resources. This strategy could be expanded to other areas as well, such as the planting of edible gardens, orchards, and remediation projects that bring biodiversity to the neighborhood.

A CLT-led planting initiative can stitch a patchwork of gardens into the residential fabric, subverting the separation between productive and residential land use typical of conventional urban planning.

As these endeavors take hold, they begin the slow work of transformation. The spatial boundaries of the parcel become less and less definitive—both spatially and socially—and from within an existing urban fabric, a new patchwork of land use emerges, knitting together dwellings, food production, buildings, and community. Together these changes structurally alter the urban form, even as the existing zoning is left undisturbed. As private lots become sites of cooperative labor, neighbors might take down fences along their property lines to create a more densely inhabited and productive neighborhood. Over time, the neighborhood develops in an atypical fashion, with the parcel structure inherent to single-family residential zoning blurred into a heterogeneous landscape of gardens and dwellings.

The dissolution of the parcel through cooperative maintenance is a transformation-in-place, where the value of land is seen through a different lens: its ecological value, its productive capacity, and its ability to create new social bonds through its stewardship and cohabitation. A new form emerges through premeditated planning, although it is nevertheless projected to take an unknown shape in the future. Ultimately, it is this form, the embodied outcome of the CLT’s spatial initiatives, that provides the conditions for development without developers and density without displacement, over time.

Labor

Blurring property lines hinges not only on a CLT’s ability to establish new terms of ownership, but also on residents’ willingness and capacity to engage in acts of maintenance and care. And while the readiness of the community should not be idealized, there is an urgent need to rethink how the built environment is produced. Re-imagining how self-sustaining community systems might alter the urban environment is a starting point. In other words, from the standpoint of design, it is not a matter of assuming that the time and labor of residents is available, but rather of considering how the systems and organizations that produce the built environment can change and might perhaps support new forms of cooperation. A reimagined CLT is central to this, since it can create new social structures that residents can opt into.

The precedents for networks of shared labor are many. Communal labor, for instance, can be defined as labor that is organized by a community for a common objective, following convocation. Individuals and households benefit from the shared resources and a collective effort. Another example is reciprocal labor, a form of mutual aid where people or groups take turns performing labor in order to lighten the burden otherwise placed on any one individual or family. Those who participate benefit from a circuit of reciprocity or mutual aid.2

Incorporating work cooperatives into the structure of a CLT, say, for construction and planting, reinforces the potential to spatially redistribute the burden of maintenance across lot lines. This redistribution may also provide an incentive for residents to join the CLT, since membership would open access to these labor cooperatives. Furthermore, if these cooperatives choose to follow a model of reciprocal labor, residents who want work done on their property would also be required to work on the properties of others.

The work undertaken by CLT-based cooperatives would follow a seasonal flow, both because planting and construction must respond to seasonal weather conditions and because projects are driven by self-initiated community mobilization, which is contingent upon resident availability, capacity, and interest. Change might take place slowly, but, nevertheless, without a market imperative to force unnecessary construction, CLT projects would happen when needed or wanted, with cooperation and collectivism making resources available in new ways. Community workdays would lower the barrier to entry for new projects and create new conditions under which a construction project might take place.

Cooperative endeavors can also operate as a crucial element in the proper functioning of a CLT. In San Ysidro, low-income residents that own their homes may value the intergenerational wealth that owning property can provide. For this reason, they may not be incentivized to accept anything that will limit their home’s long-term appreciation and refuse to join the CLT. However, if membership in the CLT also guarantees access to these networks of cooperative labor, then residents might accept a more conservative appraisal of their home value in exchange for the permanent availability of assistance with maintenance and improvement. The act of decommodifying land, then, is less about taking away what the market would otherwise offer, and more about creating new opportunities, offering what the market cannot.

Knowledge

Construction and stewardship of the built environment require knowledge and skill. Labor cooperatives can offer educational infrastructure as workdays can serve as trainings. The CLT can lend staff support, especially at first, to ensure that all participants have the knowledge and tools needed to begin the work. However, over time, more and more residents would have the ability to lead workdays, showing an increased self-sufficiency and greater potential to earn higher wages in the job market with their new skill set.

Architects might play a role as well, collaborating with CLTs to provide the design and material expertise needed to engage the work of the cooperatives. However, for this to work, the typical architect-client relationship would have to be rewritten. With the decommodification of land, labor, and knowledge as a goal, the CLT would likely be unable to hire an architect for every project. However, an architect could engage the CLT from the onset of the cooperative, not only thinking through the material logics and design configurations that would most effectively achieve long-term transformation, but also providing “design kits” that consist of building details and architectural layouts. Every time a unit addition is built in the neighborhood, members can refer to this series of drawings, or “custom standards,” eventually learning the technique themselves.

The goal of deploying custom standards is not to standardize aesthetics, but to create a method that is teachable and replicable in the community. In other words, the architect becomes an active participant in urban planning and design by offering models, patterns, and techniques that are then appropriated by the community. This, in turn, allows the custom standard to serve as an anchor for a larger cultural project, where culture is defined as the characteristics and knowledge of a group of people, including language, social habits, music, arts, and modes of building. Far from positing an architecture without architects, this way of working seeks to produce a community that re-establishes the significance of architecture as something that is vital for its growth, organization, and preservation, which in turn creates legibility of the community itself and offers a starting point for the development of vernacular knowledge after centuries of its erasure under global industrialization.

The following scenarios portray a reimagined CLT from a resident’s point of view, depicting how one’s engagement with a CLT could begin to transform a site, and eventually, a neighborhood.

Scenario depicting cooperative-run construction projects amongst neighbors.

Scenario A

A San Ysidro resident joins the CLT. To take advantage of their membership, they decide to replace their chain link fence with a hydroponic system provided through the CLT’s custom design standards. They join the planting cooperative and over the course of several weekends, the system is built and the hydroponics are up and running. Eventually, their next-door neighbor joins the CLT as well. Excited by the hydroponic fence next door, they also join and request help from the planting cooperative. After the new system is installed, a continuous and verdant street front is created along both properties.

Neighbor 1 keeps working with the CLT to build an accessory dwelling unit. As part of the CLT’s climate resilience strategy, the CLT is working with local architects to introduce rammed earth building techniques in the neighborhood, with the long-term goal of replacing timber frame construction in this fire-prone area. Local architects collaborating with the CLT provide construction detail standards for rammed earth, which are then used by the CLT’s construction cooperative. Over the course of the summer, the construction cooperative is busy on site, engaging people of all ages to build up the rammed-earth structures and host community build days.

After the success of Neighbor 1’s construction project, Neighbor 2 becomes interested as well. They realize, however, that since both of their lots are owned by the CLT, together they can request a lot consolidation. In doing so, they can connect their unit additions, ultimately getting more square footage. They take down the fence between their properties and prepare to build something together.

The construction cooperative returns to the site, building a new unit addition and a shared laundry space that connects to the first structure. After several years, both neighbors are now avid participants of the planting cooperative. They request assistance from their fellow members, eventually adding a small orchard to their garden.

Scenario depicting the utilization of large dormant lots.

Scenario B

A family with a large but largely dormant lot joins the CLT. In their first season, they work actively with the planting cooperative to plant native vegetation and fruit trees, all of which are very low maintenance once established. These plantings, however, only fill about half of the yard, and they want to rehabilitate more of the currently bare ground. Through the CLT, they learn about the Miyawaki method, a planting technique that creates high-density native mini-forests that absorb carbon and require zero maintenance after three years. Soon, they work with the planting cooperative to plant a low-maintenance carbon sink in the backyard, filling the garden with flowers, butterflies, and birdsong.

After a few years, the neighbor to the south joins the CLT as well. Because both families have low incomes, they discuss the possibility of requesting a lot consolidation and working with the CLT to build rental units in the back. With administrative help from the CLT, the families consolidate their lots and remove the fence between them. They work with the CLT construction cooperative to build a five-unit structure. Each family rents out two units, receiving a new source of income, and the fifth is rented out by the CLT itself. The CLT, through a ground-lease, regulates their affordability. Finally, the mini-forest is expanded to continue the process of environmental remediation and eliminate the need for yard maintenance in the future.

In both scenarios, the CLT supports cooperative initiatives and becomes a hub for generative and regenerative work otherwise made impossible by the existing spatial and juridical order of real estate and property. The political potential is enormous, since these models of collaboration can mobilize social labor in a way that reduces dependence on market forces, increases self-sufficiency in the community, allows for the transfer of knowledge between generations, and supports neighborhood-scale initiatives that are too large for individuals to take on while also outside the scope of municipal jurisdiction. In addition, a deep spatial subversion has occurred. With cooperative labor working over and across property lines, the power of the parcel to atomize and subdivide is diminished, even as the boundaries themselves are legally left intact. Yet the immutable lines of property are nonetheless transgressed, and a new heterogeneous urban form emerges from within the old.

It would also loosen the grip of carbon modernity. See Elisa Iturbe, “Architecture and the Death of Carbon Modernity,” Log 47 (2019).

Massimo de Angelis, Omnia Sunt Communia: On the Commons and the Transformation to Postcapitalism (London: Bloomsbury, 2017).

In Common is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, the Chicago Architecture Biennial, UIC College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts, and arc en rêve within the context of its exhibition “common, community driven architecture.”

Category

Subject

Production assistants: Sara Alajmi, Deo Deiparine, and Andrew Song. Special thanks to Casa Familiar and Andy Sturm.