A Socially Engaged Design Practice

Since 2011, the Studio in Experimental Design at the HFBK Hamburg has been offering support to people in the neighborhood of St. Pauli and elsewhere in the city who, for economic or socio-cultural reasons, do not have access to or are prevented from wielding the agency of design. For the past ten years, we have hosted open Public Design Support sessions every Wednesday from 6–7pm in the storefront space of GWA St. Pauli, a social association that has been doing community work in the community for decades. In these weekly consultations, students pick up requests from local residents and work together with them to address the everyday problems they bring. All kinds of personal or collective issues, ideas, and desires are the starting point for design projects.

In recent years, St. Pauli has undergone unprecedented change, from which its local population has been largely excluded or negatively affected. At the beginning of the 2000s, St. Pauli was the poorest neighborhood in West Germany and characterized by a culture of solidarity between former harbor workers, immigrants, and diverse subcultures, including participants in the Hafenstrasse squatting struggles and the Reeperbahn red light district. Recently, however, St. Pauli has become the most expensive district in Hamburg for new rentals. Through the conversion of tenements into condominiums, new real estate developments, and municipal housing associations focused on maximizing profits, an unmistakable displacement has and continues to take place.

Public Design Support intends to intervene in these urban processes by testing and deploying an alternative design practice. Design can contribute to generating autonomous living conditions and counteracting the powerlessness and dependence people often experience within exclusionary urban development policies. Yet most residents of working-class neighborhoods and others affected by gentrification would typically be unable to afford design, not to mention even think about laying claim to its agency. As a clearly partisan practice, we work with those who are not only excluded from urban development but also from design itself.1 We advocate for the “Right to Design,” which regards design as a fundamental human act and undisciplinary practice by which people can improve their material conditions and social wellbeing, and represent their claims as citizens.2

We have realized about a hundred design projects in St. Pauli and beyond.3 The design consultancy has worked for a pub in trouble, solved a single mother’s storage space problem, co-developed a semi-public dye garden, dramatized a demonstration by refugees, redesigned a drug counseling center, erected a memorial for relatives of concentration camp prisoners, supported rent protests, designed a cozy tutoring room, installed a loft bed with a cat tree, helped move a non-profit counseling center for refugees, renovated a broken trailer, stretched a tent across an apple meadow, laid bricks for a group barbecue, transformed an undemocratic classroom, and more.

Many of these projects ended up either unfinished or not meeting expectations. Some have ended in frustration and exhaustion, while a few others in friendship and fun. But while Public Design Support worked as a pedagogical experiment in an academic context, when viewed as an alternative model to design practice, we by and large failed. The shortcomings of Public Design Support (in terms of its aspirations) become particularly visible when it is classified in the wider category of “Social Design.” It is hard to say if any projects achieved any substantial social benefit, or if they only smooth the experience of poverty, exclusion, and exhaustion. But what they do, I would argue, is problematize our conceptual understanding of the social and the way it grounds design practice.

Once a week, Wednesday from 6 to 7 pm: Discussing while waiting for clients and friends of the neighborhood in front of our Public Design Support Center at GWA St. Pauli. To invite more of them we redesigned and translated our flyer into 11 languages and expanded the old info-leaflet with new pictures. Studio Experimentelles Design, 2011-2023.

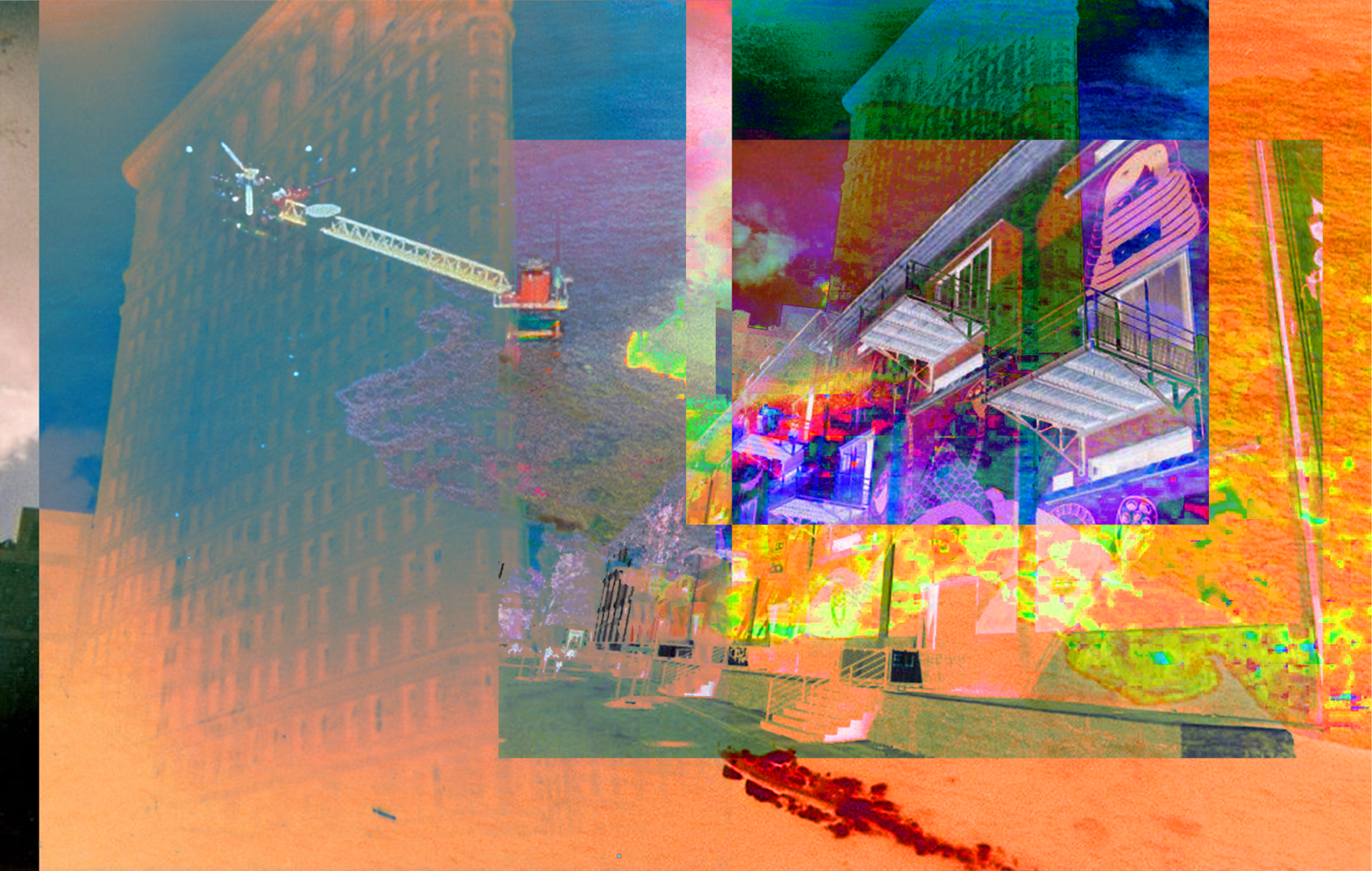

Public Design Support accompanied the planning process for the upper floor of Hamburg’s Golden Pudel Club as a neighbourhood-oriented event space, office and archive, with a series of workshops. The team was supported in intervening in the planning process from the user’s perspective and in developing perspectives for later expansion and use. Steffen Albrecht, Marie-Theres Böhmker, Kim Fleischhauer, Ilja Huber, Gvantsa Jiadze, Dennis Nedbal, Merlin Reichart, Benedikt Schich, Golden Pudel Club, 2017.

Together with the refugees accommodated there and committed neighbors, the design consultancy was able, among other things, to renovate the shower rooms and add curtains to the double bunk beds in the four- to eight-bed rooms for a little more privacy. Jonas Becker, Anna-Maria Resei, Jeffrey Wallner, Mattea Weihe, Philipp Wetzel & Refugee Accommodation Lübeck, 2016.

Once a week, Wednesday from 6 to 7 pm: Discussing while waiting for clients and friends of the neighborhood in front of our Public Design Support Center at GWA St. Pauli. To invite more of them we redesigned and translated our flyer into 11 languages and expanded the old info-leaflet with new pictures. Studio Experimentelles Design, 2011-2023.

The Desire for Community

While embraced by many well-intended designers, planners, (social) workers, artists, and activists, the term “Social Design” is not only problematically underdefined, but also misleading. It is misleading because it implies that there is such a thing as “non-social” design, and thus fails to recognize and even obscures an essential character of design: that it is always socially integrated and operative. While there is design that disavows the social, or has detrimental effects on it, if it is not social, it is not design. Societal effect and its situatedness in social structures are design’s inescapable foundations. As opposed to the term “social design,” then, “socially-engaged design” focuses not so much on the fact of design’s social character, but rather its active, critical, and political engagement with the social’s potential.

Public Design Support is predicated on making the anger, problems, desires, conflicts, and ideas from the St. Pauli neighborhood the starting point of design. Its social engagement is therefore based on design commissions formulated by local groups and individuals. Public Design Support is deliberately dependent on people and their issues, and on being accepted into the existing neighborhood’s social dynamics and conflicts. This, however, is always easier said than done. Language barriers, invisible hierarchies, everyday trouble, misunderstandings, timing, and very tangible difficulties like money and weather create barriers and made us inaccessible to people who have limited resources to engage in the arduous process of co-creation. Further, Covid-19 made us completely lose contact with the neighborhood.

We are currently in the process of rebuilding our relationship with St. Pauli. We are back on site, hanging out and chatting with people. We are informing neighbors with flyers in different languages, and have started to meet more regularly with community organizers and social workers. At the same time, we are reflecting on how we can work in a more accessible and needs-based way. We have extended our opening hours and are making an effort to communicate more simply (and in more languages) what we can offer and how we work. We have invited neighborhood initiatives to informal get-to-know-you talks, and even arranged to meet with the local priest. We desperately want to get to know the district better. We want to open up to the community. We want to be part of the neighborhood. We want to work on local problems.

Statements such as these reproduce tropes that inform and establish the horizon for many contemporary artistic, architectural, and design practices: the community, the local, the neighborhood, the borough. These terms, taken from the arsenal of socially-engaged design practice, point to the fact that the values and criteria that define contemporary design are not the profession, the firm, the academy, the market, consumer desires, or even legal regulations. Rather, it is smaller social units with everyday knowledge and experiences of reality that build design’s contemporary frame of reference. The community, the local, the neighborhood, and the borough ensure a connection to people’s life worlds and make it possible to relate to (and resist) everyday experiences.

In many socially-engaged design and art practices, the concept of “community” often stands in for what was formerly meant by the term “social.” In current approaches like community-based design,4 community-led design,5 community-driven architecture,6 or community-centered design,7 the socio-spatial category of community frames the idea of social engagement and allows it to become practical. In contrast to the “social,” then, “community” seems to evoke emancipatory connotations and allows them to be concretely grasped and located. But the idea of community cannot replace the politics of the social.

We designed the WiQ (We in the Quarter) neighborhood café as a non-commercial meeting place in the Winterhude district to build up a civic network in which people from very different walks of life come together. Together with the initiatives, we developed a large-scale seating module that uses existing chairs and tables from the church’s stock. Benjamin Bakhshi, Béla Dizdar, Mia Lotta Gabele, Jan Wilbert Juchem, Marieke Schröder, Kayoung Kim, Cathrin Zumhasch, 2022.

The Return of the Social as Unsocial

The idea of the social—the “social” as in social contract, social insurance, social state, socialism, social housing, social welfare, and social justice—is based on the promise of a more or less equal, just, whole, and interconnected society. This idea, however, has been buried by neoliberalism’s efforts to confuse us about the power of individualistic market forces. A community, conversely, is sociologically defined as a group of people who share a common history or ethnic background, live in a certain area, cultivate common interests, or feel committed to joint values. While society is a historical agreement that urges compliance in order to bring about togetherness, community often represents itself as something well-arranged and given in advance.

Community often appears natural, instinctive, and plausible. Society, conversely, is generally understood to be constructed, negotiated, formed, accepted, and cultivated. The idea that communities are representative formations of society, however, is just as constructed as claims of national or even international societies. Families, for instance, are kept together by biological chance and patriarchal traditions. Friendship is similarly constructed by uncontrollable love and brutal mechanisms of social selection, biased perceptions, and class distinctions. Colleagues are selected by educational systems, hierarchies, gender, status expectations, and mostly, the labor market. Neighbors are produced by the real estate market, date of birth, milieu-specific choices, and forced (re-)locations due to poverty, war, or the climate crisis. A borough is created by strategic administrative reforms, electoral considerations, urban planning decisions, socio-spatial segregation, gentrification, urban marketing, or romanticized memories. Communities, in short, are not natural.

In recent decades, the idea of community has been subject to wide-ranging theoretical debates about alternative approaches to political space beyond individualism and the state-structured society. In contrast to the affirmative use of “community” in social design and other engaged practices, these reflections share the assumption that community is not a given emancipative reservoir but, on the contrary, a principle that reveals great political ambivalence and has to be carefully deconstructed. The philosopher Joseph Vogl, for example, elaborates on the problematic tendency of communities to seclude themselves, and argues for a “de-totalization” and “de-localization” of the concept of community.8 For Roberto Esposito, it is precisely the tendency of community to function as a locus of identity that requires its permanent deconstruction in order for it to serve as a possible goal of emancipatory politics; he thus argues for community without property, without essence, and without territory, but with lack and a shared obligation.9

In the context of neoliberal efforts to replace the organizational function of politics by the market, the call for local- and community-based dynamics represents not only a potentially essentialist turn but another tool for social deregulation. Neoliberalism always takes place in regional or local contexts and relies on the difference of institutional, social, and political parameters. It positions localized communities in contrast to the state as a dominant place of market governance. This contextualism explains how the “revival of the local” and of community occurs at the very moment “when allegedly uncontrollable supra-national transformations are underway.”10 The shift from society to community should be understood as a technique of governance based on accepting and promoting groups of people with different income, health, education, access to culture, ecological concerns, and standards of life. The rise of community as the new social shifts focus from a comprehensive social space to differentiated and manageable zones of communities.

The spread of community and its subsumption of the social in fields of management, work, administration, and planning must be read against the backdrop of neoliberal power techniques and market arrangements. Already in 1996, social scientist Nikolas Rose observed a market interest to define consumer groups with shared experiences and an interest by planners, pedagogues, police, and politicians to sort people into territories and interests to better understand and target them.11 He proclaims that “Community has become a new spatialization of government: heterogeneous, plural, linking individuals, families, and others into contesting cultural assemblies of identities and allegiances.”12 This new “government though community” is based on the decoupling of social welfare from national strategies of governance, and on the differentiation between “those who are considered to be competent citizens and those who are not.”13

According to Rose, governing through community is articulated in a number of shifts: spatially, from the terrain of the state to the locality of different communities; socially, from regulation and welfare to individual and voluntary community involvement; and subjectively, from state citizens to personally chosen or given identities that derive from direct, emotional, tangible, traditional, spontaneous, and other community relationships.14 These phenomena crucially obscure the distinctly neoliberal ideology of “instrumentalizing the self-governing properties of the subjects of government themselves in a whole variety of locales and localities—enterprises, associations, neighborhoods, interest groups and, of course, communities.”15 These overarching shifts in governance have been mirrored by architects, planners, and designers. Following historian and cultural scientist Christa Kamleithner, current planning tendencies actively strive for a neighborly differentiation of space, and attempt “to guide individuals, neighborhoods, and regions to self-awareness”—as communities.16

Community is a constructed, calculable, and governable form of diversity that allows for subtler management and better market integration. It is an intermediate formation that enables the individual to be governed without the burden or responsibility of managing the whole of society. “Dissociated into a variety of ethical and cultural communities with incompatible allegiances and incommensurable obligations,” community is the opposite of the social.17 Contemporary discourse on community tends to discredit society as a sphere of representation of the social, and thus pushes social issues such as poverty, exclusion, discrimination, climate justice, environmental degradation, and racism out of the field of vision. From this perspective, community is unsocial.

The residents’ initiative Runder Tisch Hansaplatz has been campaigning for years for consumer-free seating and against repressive police interventions like CCTV on Hansaplatz. A weekend-long activist trial sitting intervened in the conflict-ridden situation to try out a new coexistence. Anna Ulmer, Irini Schwab, Maren Hinze, Tatjana Schwab, Tina Henkel, Runder Tisch Hansaplatz, 2022.

The activist refugee group Lampedusa in Hamburg asked us for support in the fight for their location in front of the central station. Together we developed a performative monument to draw attention to the Lampedusa tent and to create a platform for the group’s political announcements. Olivia Amon, Sofia Dos Santos, Veronica Andres, Studio Experimentelles Design, Lampedusa in Hamburg Group, 2022.

The residents’ initiative Runder Tisch Hansaplatz has been campaigning for years for consumer-free seating and against repressive police interventions like CCTV on Hansaplatz. A weekend-long activist trial sitting intervened in the conflict-ridden situation to try out a new coexistence. Anna Ulmer, Irini Schwab, Maren Hinze, Tatjana Schwab, Tina Henkel, Runder Tisch Hansaplatz, 2022.

A Strategically Partial Perspective

Communities, however, do not necessarily have to be understood as the neoliberal antithesis to society. They can also be seen as a relevant and operational dimension of it. For Lisa Peattie, an anthropologist, co-founder in the 1960s of the pioneering advocacy planning group Urban Planning Aid in Boston, and one of the forerunners of the movement that later became known in the US as “Community Design,” communities were at the same time naive and strategic constructions: problematic conceptions, yet necessary to establish, practice, and promote a new political design practice.18 According to Peattie, prior to community design, advocacy planners tended to not only oversimplify issues but also homogenize communities, overlooking their internal contradictions and the multiplicities that result from conflicting interests. They would also often underestimate the political power of their own actions and processes, paternalistically choosing communities and formulating topics.19 For this reason, Peattie and her colleagues never forgot to include the broader context—or, in other words, the social—in their design support for a neighborhood.

From a similar perspective, a recent debate among the youth and the radical left in Germany reflects on the relationship between politics and local initiatives for community engagement. The Berlin Kiezkommune Wedding, Kreuzberg-Neukölln, and Friedrichshain, for example, relate their approach of creating neighborhood-organized communes to political models of organization such as the council system of the Weimar Republic or the Kurdish commune in Rojava.20 Based on concrete concerns for the affairs of their respective communities, they argue that district councils should be organized on a supra-regional basis with a mandate and mechanisms of accountability.21 Another group, called Kollektiv aus Bremen, argues that building self-organized structures of power and resistance in relation to local conflicts can become the starting point of wider struggles.22 In this sense, work, housing, reproduction, health, education, and food are community-based fields of action from which an awareness of everyday issues within a larger social context can be grasped and resisted.23

These activists build on the efforts of tenants, residents, and/or workers to organize concretely for their concerns. In this sense, community understood as grassroots organizing does not disavow but is motivated by a revolutionary claim about society as a whole. Both groups explicitly point out the limitations of a local perspective and see community as a strategic element in a broader struggle. The local or the neighborhood are thus understood as potential sites for the construction of counter-power, with the aim of developing, testing, and strengthening resistant social perspectives and solidarity in everyday practices. In this context, the difference between community and the social is acknowledged, and sociopolitical engagement is not reduced to community work. Rather, societal challenges can be approached via everyday realities that can be experienced and shaped locally, but have broader implications and connections.

For socially engaged design practices, it is essential that well-intentioned references to community do not reproduce the managerial segmentation of the social. A political perspective on design that draws merely from the on-site needs of supposed communities too often ignores underlying contexts and power structures that might not be immediately present or visible. Local neighborhoods may be useful as strategic sites for the exploration of social problems and for the effective binding of design processes to alternative protagonists and issues. However, they do not promise social relevance. Individual experiences and concerns, as well as larger societal upheavals, are not necessarily represented or experienced, let alone adequately addressed and shaped within the framework of community. This particularly applies to questions of social justice, the demand for which cannot be limited to spatially, culturally, or ethnically fragmented spaces, and which presuppose a view of society as a larger whole.

Spatial categories such as community, neighborhood, the local, or the district can only be meaningfully activated as a strategic and political ground for design outside of an essentialist or neoliberal framing. This well-intended approach can only avoid becoming unsocial if community is no longer understood as a substitute for society, but instead as a correlate to the social. A partisan perspective of design must not only take up group interests, but must also avoid assuming the naturalness of their social arrangements. Socially-engaged design needs to directly address concrete concerns and the struggles of groups, networks, districts, classes, initiatives, and neighborhoods precisely at the critical point of rupture between community and society.

The “How to Gestaltungsberatung” online tutorial, developed in 2019 for the Hamburg Open Online University, provides insight into the working methods and thinking space of Public Design Support. See ➝.

See for example the lecture “The Right to Design” by Henric Benesch and Onkar Kular, in Parse no. 12 (Autumn 2020), ➝.

See the project website ➝ and the two books on Public Design Support: Jesko Fezer & Studio Experimentelles Design, ed., Öffentliche Gestaltungsberatung: Public Design Support 2011–2016 (New York, 2016); and Jesko Fezer & Studio Experimentelles Design and Claudia Banz, eds., (How) do we (want to) work (together) (as (socially engaged) designers (students and neighbors)) (in neoliberal times)? Public Design Support 2016–2021 (New York, 2021).

Coopdisco and Mathias Heyden, Community Based Design Center (Berlin: Bezirksamt Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, 2020.

Sasha Costanza-Chock, Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020).

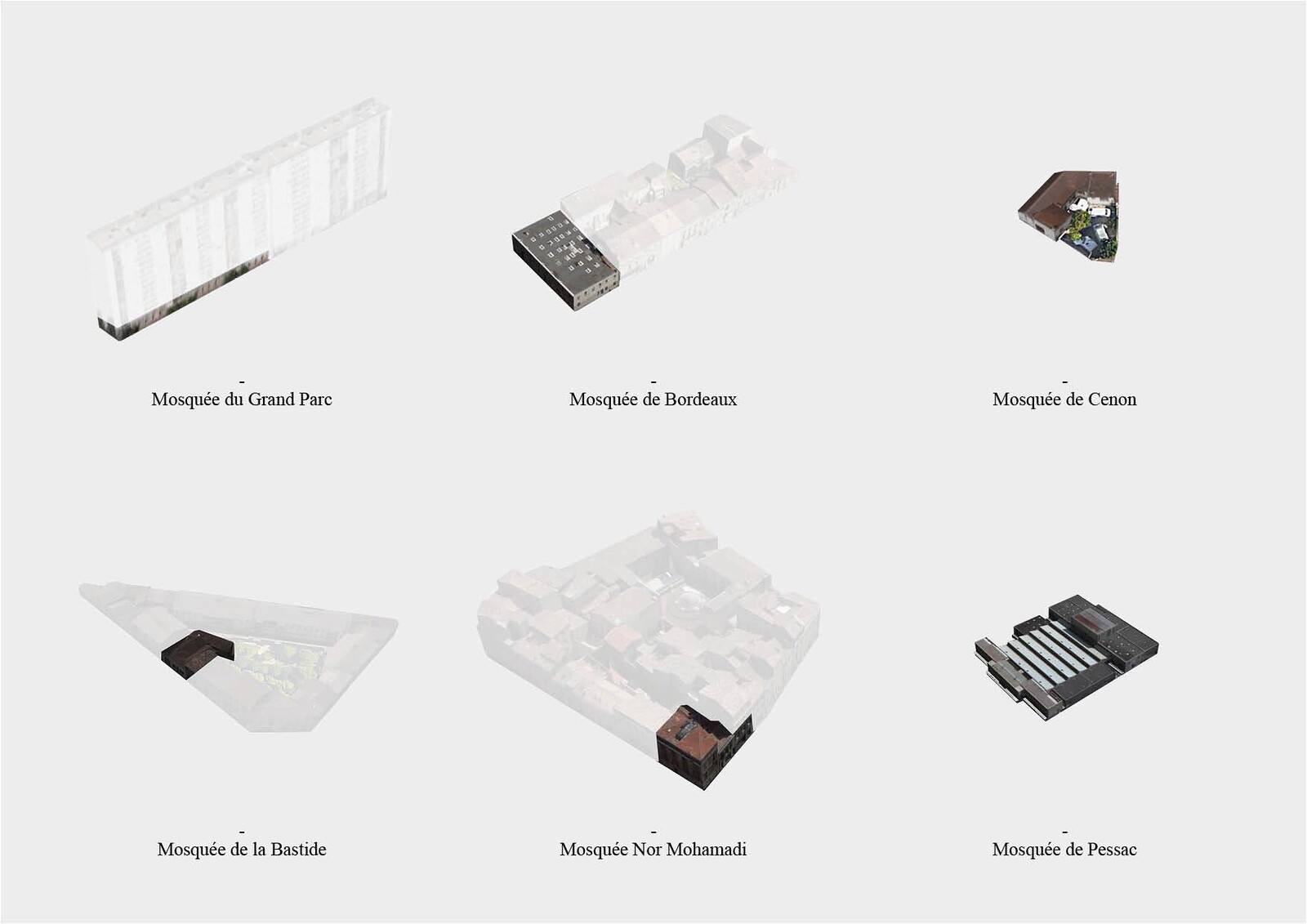

See the exhibition this essay is for: arc en rêve centre d’architecture Bordeaux, “common, community driven architecture,” June 23–September 18, 2022.

Don Norman and Eli Spencer, “Community-Based, Human-Centered Design,” jnd.org, 2019, ➝.

Joseph Vogl, “Communal Spaces / Community Places / Common Rooms: De-totalized Forms of Encounter,” An Architektur no. 10, (Berlin and New York: An Architektur, October 2003). See ➝.

Roberto Esposito, Communitas: The Origin and Destiny of Community (Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2010).

Neil Brenner and Nik Theodore, eds., Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003); Jesko Fezer, “Design for a Post-Neoliberal City,” e-flux Journal no. 17 (June 2010), ➝.

Nikolas Rose, “The Death of the Social? Re-figuring the Territory of the Government,” Economy and Society, no. 3 (August 1996): 327-356.

Rose, “The Death of the Social?,” 327.

Ibid.

“The vocabulary of community also implicates a psychology of identification; indeed the very condition of possibility for a community to be imagined is its actual or potential existence as a fulcrum of personal identity. Yet these lines of identification are configured differently. Community proposes a relation that appears less ‘remote,’ more ‘direct,’ one which occurs not in the ‘artificial’ political space of society, but in matrices of affinity that appear more natural. One’s communities are nothing more—or less—than those networks of allegiance with which one identifies existentially, traditionally, emotionally or spontaneously, seemingly beyond and above any calculated assessment of self-interest.” Rose, “The Death of the Social?,” 334.

Rose, “The Death of the Social?,” 352.

Christa Kamleithner, “Regieren durch Community: Neoliberale Formen der Stadtplanung,” in Governance der Quartiersentwicklung. Theoretische und praktische Zugänge zu neuen Steuerungsformen, eds. Matthias Drilling and Olaf Schnur (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2009), 29-47, 45.

Rose, “The Death of the Social?,” 353.

The 1960’s Advocacy Planning movement that emerged alongside this transferred what was then the new idea of community organizing—a form of active neighborhood support as developed and coined by Saul Alinsky—to the field of design and planning, applying their skills and resources in the service of local groups. See Jesko Fezer, Umstrittene Methoden. Architekturdiskurse der Verwissenschaftlichung, Politisierung und Mitbestimmung in den 1960er Jahren (Hamburg: Adocs, 2022); Lisa R. Peattie, “Communities and Interests in Advocacy Planning,” Journal of the American Planning Association, no. 2, (1995): 151-153.

Lisa R. Peattie, “Reflections on Advocacy Planning,” Journal of the American Institute of Planners, no. 3 (1968): 80-88.

radikale linke berlin, Kiezkommune Wedding, Kiezkommune Kreuzberg-Neukölln, Kiezkommune Friedrichshain, “Das Konzept Kiezkommune: Über Gegenmacht und wie wir sie aufbauen,” Kiezkommune Aufbauen, ➝.

radikale linke berlin et al., “Das Konzept Kiezkommune.”

Kollektiv aus Bremen, “Für eine grundlegende Neuausrichtung linksradikaler Politik: Kritik & Perspektiven um Organisierung und revolutionäre Praxis,” 2016, ➝.

Kollektiv aus Bremen, “Für eine grundlegende Neuausrichtung linksradikaler Politik,” 37.

In Common is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, the Chicago Architecture Biennial, UIC College of Architecture, Design, and the Arts, and arc en rêve within the context of its exhibition “common, community driven architecture.”