Martin Ritt’s 1965 adaptation of John Le Carré’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold opens at Berlin’s Checkpoint Charlie, one of the then-divided city’s few permitted crossing points. From our very first glimpse of the tangled barbed wire atop a roughly cemented cinder-block wall, we feel we are looking at Berlin. The harsh sodium lights glaring upon the glistening cobblestones and poised barrier arms join with impassively waiting soldiers and ominous blockhouses to confirm our supposition. We read “YOU ARE LEAVING THE AMERICAN SECTOR” on the multilingual sign and know we are in Cold War Berlin.

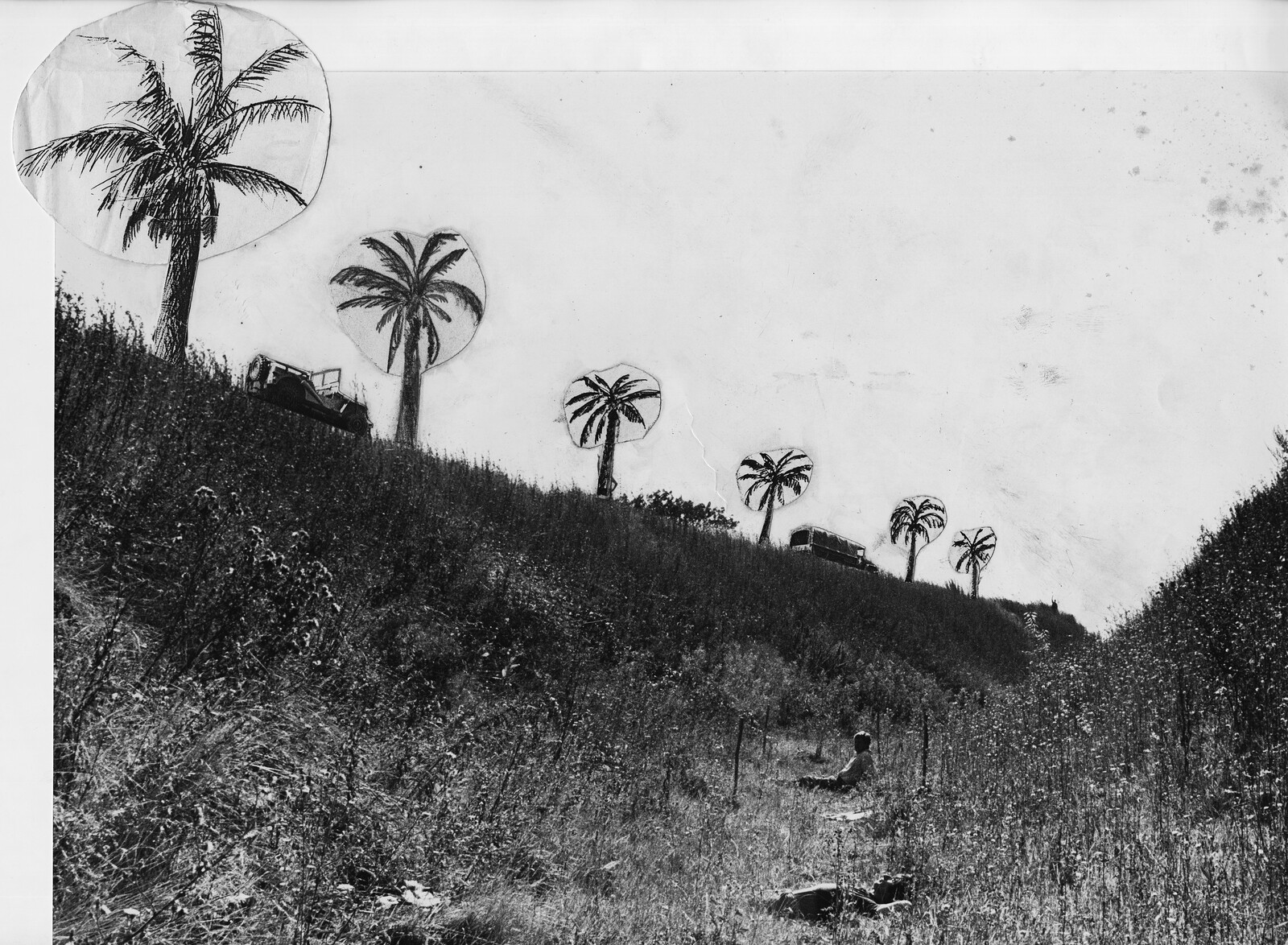

Except we aren’t. This ersatz version of Checkpoint Charlie was built in Dublin’s Smithfield Market Square. It should not be a surprise that the actual Berlin Wall was out of bounds for filming in 1965, especially since the film’s tragic final scene takes place at a different, even more inaccessible locale: the inner, East German side of the wall. While North Dublin in the 1960s may have shared much of Berlin’s sooty grimness and careworn appearance, the re-constructed checkpoint looks very little like the Berlin original. Many of the same elements are present, but their configuration is quite different, as are the neighboring buildings.

Should this inability to precisely reproduce Checkpoint Charlie be seen as a strike again the authenticity and realism of Ritt’s film? Is it an error, one that twenty-first century computer-generated imagery software could easily correct? Of course not. That part of Dublin could credibly stand in for part of Berlin takes us beyond questions of normative film making practice and plausible resemblance. Instead, it highlights the extent to which certain stereotypical features of Berlin’s Cold War landscape circulated around the world through film, television, and other media, to the point that an idea of Cold War Berlin, removed from the immediacy and materiality of any actual place, took hold in the global imagination.1 At a time when the Berlin Wall had largely lowered the city’s temperature and shifted the focus of the Cold War elsewhere, its symbolic presence was multiplied exponentially by films that cemented Berlin’s reputation as a city of intrigue and action.2

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold exemplifies the cinematic construction of an “analogous” Berlin, a term used by the Italian architect Aldo Rossi in his book The Architecture of the City. Rossi illustrated this concept using Canaletto’s Capriccio of Palladian Buildings (1756–59), a quintessential Venetian scene depicting two buildings and a bridge, none of which can be found in Venice. (One is unbuilt and the other two are from neighboring Vicenza.) As Rossi writes, “The geographical transposition of the monuments within the painting constitutes a city that we recognize, even though it is a place of purely architectural references.”3 In other words, our imagination associates certain shapes, symbols, forms, and signs with certain places. Film has done the same with the Berlin Wall, transforming humdrum elements into visual signifiers of a divided city, country, and continent.

One hundred and fifty-five kilometers long, the Berlin Wall stood from 1961 to 1989, providing the most tangible manifestation of the “iron curtain” that divided Eastern and Western Europe during the Cold War. For the historian Brian Ladd, it was “probably the most famous structure that will ever stand in Berlin.”4 The wall’s grip upon the city’s physical geography and collective psyche both predated its construction and has outlived the twenty-eight years of its existence, in no small part thanks to its representation in film. Before the wall was built, East German films such as Gerhard Klein’s Berlin—Schönhauser Corner (1957) warned audiences of the corrupting influence of capitalist West Berlin, thereby making the ideological case for ending the easy movement between the city’s eastern and western sectors. Historian Henning Wrage has similarly argued that film made the case—in both East and West—for the Berlin Wall; films portrayed narratives showing that “the two German societies are incommensurable.”5 As post-1989 Berlin wrestled with the question of whether to preserve sections of the wall against prevailing tides of public opinion, the city continued to export images of its previously divided self through films such as Leander Haußmann’s Sonnenallee (1999) and Wolfgang Becker’s Good Bye, Lenin! (2003). For the former, a section of the wall was rebuilt on the “Metropolitan” backlot of the fabled Babelsberg Studios in nearby Potsdam.6

The surrogate wall erected in Dublin for The Spy Who Came in from the Cold was symbolically charged but militarily impotent. It reenacted the wall’s physical tropes and psychological dramas a safe distance away from the charged border between East and West Berlin. In Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire (1987), this distance collapses to nearly nothing in a jarring yet tender moment of narrative rupture and rebirth. The protagonists in Wings of Desire are the angels Damiel and Cassiel, immortal witnesses to Berliners’ innermost thoughts and proxies for our own experiences as cinematic spectators. While the angels’ historical memory is eternal and their physical mobility is unimpeded by physical barriers, Wenders’ camera was limited by the Berlin Wall, and the film takes on the flavor of the enclave, with its graffitied concrete, open wastelands, and celebrated music scene.7

Bruno Ganz and Otto Sander in Wings of Desire by Wim Wenders © 1987 Road Movies – Argos Films. Courtesy of Wim Wenders Stiftung – Argos Films.

In the film’s most poignant scene, Damiel gives up his wings and becomes mortal. He does so in the no-man’s land, the constantly surveilled “death strip” between the inner and outer barriers—therefore entirely on East German soil—that gave the Berlin Wall its haunting thickness. The filming of this sacrificial act in an inaccessible place could not be done in situ, making this moving scene a strange visual interruption in the film, which otherwise is persistently and precisely grounded in actual Berlin spaces. Here, the analogical power of the wall’s signifiers—even when made out of ersatz materials—reigns supreme, just as it did in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. The geographical transposition this time, however, was far shorter: Wenders’ simulacrum of the Berlin Wall was built only a few blocks from the real thing.

Wim Wenders during the shooting of Wings of Desire by Wim Wenders © 1987 Road Movies – Argos Films. Courtesy of Wim Wenders Stiftung – Argos Films.

For the architect Rem Koolhaas, who studied the Berlin Wall as a student at the Architectural Association in the early 1970s, the wall “was a very graphic demonstration of the power of architecture and some of its unpleasant consequences.”8 Beautiful in direct proportion to its horror, it was the “transgression to end all transgressions.”9 Imprisoning both sides of the divided city, the wall created events, enforced behaviors, and scripted rituals that varied from the mundane and the ridiculous to the tragic. Koolhaas claimed that the wall’s importance was in no way tied to its mass or materiality. Instead, it demonstrated that erasure, absence, and void are just as, if not more, powerful than the presence of an architectural object.10 The production of Wings of Desire confirms the dissociation of architecture’s classical links between mass and meaning. As Wenders relates, “We had to rebuild the Berlin Wall sets after they got wet. Cardboard had been used in their construction and once the rain got to it, it started to warp. So this short time before the Berlin Wall came down, we had to put it up! Twice!”11

Many films, especially those shot on location in West Berlin, were able to feature the actual Berlin Wall. The most fascinating of these do so in ways that emphasize the wall’s incongruity and alterity, rather than its banal actuality. Anthony Mann’s 1968 Cold War spy thriller, A Dandy in Aspic, captures one of the Berlin Wall’s strangest conditions in a scene when the British double-agent Eberlin drives his red sports car alongside the wall on Bernauer Straße. This stretch of the Berlin Wall was made from the remnants of buildings that abutted the border. As a result, while Bernauer Straße was in West Berlin, the buildings on the south side of the street were in the east. Many of their residents—some aided by the West Berlin fire brigade—escaped by jumping from their apartment windows onto the sidewalk and into West Berlin in August 1961. Eventually, the windows of these buildings were bricked-in floor-by-floor, forcing would-be escapees to jump from higher and higher heights until finally all the buildings were evacuated and later demolished—except for their front façades, up to a height of several meters. Their ghostly presence remained until the 1980s.12

Bruno Ganz in Wings of Desire by Wim Wenders © 1987 Road Movies – Argos Films. Courtesy of Wim Wenders Stiftung – Argos Films.

Other films feature the real wall’s most normative conditions. In the 1980s, graffiti transformed the outer wall in West Berlin into a riotous canvas and one of the enclave’s main signifiers, at least for western audiences. This is visible in Wings of Desire when the newly human Damiel begins to explore West Berlin by walking along the real wall near Waldermarstraße in Kreuzberg. He asks a nearby graffiti artist to help him learn the names of the colors by referencing French artist Thierry Noir’s paintings on the wall. In real life, Noir’s graffiti was controversial: on the one hand, it showed defiance towards East Germany. On the other, graffiti seemed to normalize an abnormal condition, turning the wall from an abomination into a surface for counter-cultural self-expression.13

Given James Bond’s status as the ne-plus-ultra Cold War warrior, it is perhaps surprising that only one Bond film is set in Berlin: the largely forgettable Octopussy, directed by John Glen and released in 1983. In this case, the ubiquitous graffiti celebrated in Wings of Desire was a problem, one which could be overcome in a demonstration of the wall’s cinematic malleability. In an early scene, a clown attempts to escape from East Berlin across the wall. Since the eastern side of the wall—the side that never had any graffiti on it—was unavailable for filming, the crew painted over the graffiti on the western side of the outer wall at Potsdamer Platz.14 Here, one part of the wall stood in for another very different part, at least partially modifying its material condition and meaning in the name of cinematic illusionism. After filming was complete, the crew left their own mark, painting “007 Was Here” on the whitewashed wall.

The Berlin Wall rarely appeared in in East German films, which confirms the state’s resolute desire to focus its citizens’ attention inwards on their socialist homeland. Peter Kahane’s The Architects (1990) fictionalizes the disaffection that swept over East German society in the 1980s, and, in particular, the frustrations faced by artists working under sclerotic conditions that slowly beat idealism into despair. The film follows a collective of artists and architects led by the film’s protagonist, Daniel Brenner, as they attempt to beautify the expanses of pre-fabricated housing on East Berlin’s peripheral Marzahn estate through the introduction of public amenities and postmodern forms. The inevitable frustration and failure of their scheme, together with the general malaise plaguing East German society at the time, is communicated through a montage of East Berlin streetscapes in which the wall occupies a mute, yet prominent place. Accompanied by audio of Unsere Heimat, a children’s song praising the supposed beauty of the East German homeland, the montage lays bare the East German state’s failure. For historian Emily Pugh, the “song’s lyrics [in the film] become a commentary … of individuals’ lack of belief in or connectedness to” official ideology.15 Showing these physical manifestations of the regime’s shortcomings, which everyone knew were there but never discussed, was the ultimate sign that the game was up for the East German regime.

Kahane’s The Architects was only possible at a precise, liminal moment in German history, one in which the apparatchiks of East Germany’s state-run DEFA film studio and the Ministry of Culture could countenance and wish to represent reform, but still prior to the regime’s—and, with it, the studio’s—ultimate collapse.16 While the film was first written in 1987 as a brave critique, by the time of its release in June 1990 it had become an unwanted anachronism, seen only by a few thousand theatregoers. Filmed between October and December 1989, The Architects stands as a cinematic representation of the centrifugal and disintegrative forces that quickly eclipsed the fictionalized scenario’s capacity to keep up. While Kahane considered re-working the film to account for ongoing developments, in the end he left it almost entirely as it was envisioned before the wall’s collapse was even imaginable.17 The film thus stands both as a projective fiction and as a remnant of an outdated past.

Still from Peter Kahane, Die Architekten, 1990, showing Brandenburg Gate. Courtesy DEFA-Stiftung.

The possibilities offered by this heady moment, together with the vertiginous pace of change, created a race against time to film the penultimate scene, in which Daniel attempts to glimpse his daughter Johanna—now living in the West—from across the Brandenburg Gate. This section of the wall had been preserved, since it was to be used for a symbolic re-opening of the gate—which divided Berlin’s main east-west axis—by the West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl and the East German Prime Minister Hans Modrow on December 22, 1989. Kahane’s crew received permission to film a few days beforehand, but they had to take care to keep the massive lighting masts set up for the re-opening out of their shots. No longer a place of division, death, and despair, the authentic wall was now reduced to an oversized stage prop. Having come as near as possible to the wall at the very moment it lost its political salience, film now turned to generate its afterlife, which persists to this day. In so doing, cinema echoed the ongoing struggle to knit a once-divided nation back together. As the West Berlin writer Peter Schneider lamented, “it was the Wall alone that preserved the illusion that the Wall was the only thing separating the Germans.”18 Viewed in this light, perhaps the Berlin Wall’s persistence on our screens can help palliate the pangs of reunification by providing an imaginative realm in which this illusion can safely persist.

After filming was complete, these fragments of a pseudo-Berlin Wall were purchased by a local businessman, who erected them in front of his galvanizing plant in Dublin’s Inchicore neighborhood. Thus Berlin’s Cold War landscape continued to circulate both visually and physically throughout 1960s Ireland. Donal Fallon, “The Berlin Wall (In Inchicore),” Come Here to Me! (blog), February 28, 2013. See ➝.

In addition to those mentioned in this article, my favorite Berlin Wall films include: And Your Love Too (Frank Vogel, 1962), Funeral in Berlin (Guy Hamilton, 1966), Cycling the Frame (Cynthia Beatt, 1988), The Legend of Rita (Volker Schlöndorff, 2000), Gaz Bar Blues (Louis Bélanger, 2003), Herr Lehmann (Leander Haußmann, 2003), The Invisible Frame (Cynthia Beatt, 2009), and Rabbit à la Berlin (Bartek Konopka, 2009).

Aldo Rossi, The Architecture of the City, trans. Diane Ghirardo and Joan Ockman (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1982), 166.

Brian Ladd, The Ghosts of Berlin: Confronting German History in the Urban Landscape (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 7.

Henning Wrage, “Politics, Culture, and Media before and after the Berlin Wall,” in The German Wall: Fallout in Europe, ed. M. Silberman (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 59. For Wrage, the quintessential example of a film making the case for the wall before its construction is Günter Reisch and Hans-Joachim Kasprzik’s five-part television miniseries Gewissen in Aufruhr {Conscience in Commotion} (1961). See Wrage, “Politics,” 65–68.

Potsdam itself is home to the “Bridge of Spies” between East and West Berlin featured in Steven Spielberg’s 2015 film of the same name.

Beyond the example discussed in the following paragraph, Wenders’ film transcends the boundaries of West Berlin in two other ways. First, the angels often watch over both East and West Berlin from raised perches atop the Europa Centre or the Siegessäule (Victory Column). Second, Wenders used footage of East Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg neighborhood taken by DEFA cinematographer Thomas Plenert and smuggled across the border by the actor Hans Zischler. The ease with which the angels appear to pass through the wall in this scene is inversely related to the difficulty of acquiring these few seconds of footage. See Conrad Menzel, “Die ganze Stadt,” der Freitag, September 23, 2012. See ➝.

Rem Koolhaas, “Field Trip: (A)A Memoir: The Berlin Wall as Architecture,” in Small, Medium, Large, Extra-Large by Office for Metropolitan Architecture, Rem Koolhaas, and Bruce Mau (New York: Monacelli Press, 1995), 226.

Koolhaas, “Field Trip,” 225.

Koolhaas, “Field Trip,” 228.

Richard Luck, “Angels of old Berlin: An oral history of Wings of Desire,” The New European, October 27, 2022. See ➝.

Ladd, Ghosts of Berlin, 34.

Ladd, Ghosts of Berlin, 26–27.

Julia Nikschick-Röhlig and Marc Röhlig, “Writings on the Wall,” Huntingbond (blog), August 30, 2015. See ➝.

Emily Pugh, Architecture, Politics and Identity in Divided Berlin (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2014), 313.

The internal power struggles in late-1980s DEFA are recounted in Marco Bohr, “The Collapse of Ideologies in Peter Kahane’s The Architects” in Frontiers of Screen History: Imagining European Borders in Cinema, 1945–2010, ed. Raita Merivirta, Kimmo Ahonen, Heta Mulari, and Rami Mähkä (Bristol: Intellect, 2013), 65–90.

Kahane and his crew were filming on the night of November 9, 1989, when the Berlin Wall came down. See Sebatian Heiduschke, East German Cinema: DEFA and Film History (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 125.

Peter Schneider, The German Comedy: Scenes of Life After the Wall, trans. Philip Boehm and Leigh Hafrey (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1991), 13. Quoted in Ladd, Ghosts of Berlin, 30.

Impostor Cities is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and The Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto within the context of its eponymous exhibition, which was initially commissioned by the Canada Council for the Arts for the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale.

Category

I am grateful to Nick Axel, Thomas Balaban, Eve Blau, Hugh Campbell, Joseph Clarke, Dominique Hamel, Brian Ladd, Hannah Paveck, Jessica Schouela, Robin Schuldenfrei, David Theodore, Jennifer Thorogood, and Maria Zinfert for their kind suggestions as I have studied the Berlin Wall’s many cinematic echoes.