It’s August, 1971. Things are generally quiet on campus at Simon Fraser University (SFU), the newly constructed modernist icon from architect Arthur Erickson, set upon a grand hill overlooking Vancouver’s downtown core and its backdrop of the ocean harbor and north shore mountains. A Universal Studios production team has moved in to take advantage of the summer lull in student activity (and government incentives for foreign film production) to shoot their sci-fi thriller The Groundstar Conspiracy. It’s about a man named Bellamy (Michael Sarrazin) whose memory has been wiped and face surgically reconstructed to take on the identity of a man named Welles to serve as part of an investigation into espionage against a covert government operation known as Groundstar. The base of the operation is housed at a top-secret military establishment, played by the campus itself with its distinctive elevated Academic Quadrangle that resembles the architecture of the Pentagon. This film was an important precedent for Vancouver’s eventual branding as Hollywood North, and the inevitable disguising of the city that came along with it. SFU never plays a university on film, and Vancouver rarely plays itself.

Groundstar offers ample points of identification for “insiders” who can see through the projected “placelessness” of the narrative to view the film as a goldmine of documentary footage of a city on the cusp of the major changes that so many post-war urban centers were undergoing at this time.1 Yet this identification is challenged by the film’s continual aims to erase that veracity in favor of narrative demands, not unlike the plight of the protagonist whose own memory has been wiped to service a political narrative. “I still don’t know who I am,” he laments at the end of the film surrounded by Erickson’s modernist concrete angles. This statement could have just as easily been uttered by the city itself as it set about defining its own path in the wake of ubiquitous post-war modernization across the border.2

Members of the World Soundscape Project in 1973 from left to right: R. Murray Schafer, Bruce Davis, Peter Huse, Barry Truax, Howard Broomfield. Photo credit: World Soundscape Project.

At the same moment as Groundstar’s production, a team of SFU researchers, under the direction of composer R. Murray Schafer, was busy forming what they called the World Soundscape Project (WSP).3 Their goal was to study the particularities of specific locales through their sonic characteristics, and their first case study was Vancouver. “This is a portrait of your city,” Schafer wrote in The Book of Noise, the WSP’s first publication in 1970. “Listen to it closely. Perhaps you have never really listened before.”4 One of their critiques of the modern city was the pervasiveness of generic impositions on the sonic environment from things like traffic and ventilation systems mobilized by newly constructed freeways and skyscrapers of the day. Cities were losing their distinctiveness and starting to all look and sound the same, an argument echoing Jane Jacobs’s warnings about “the self-destruction of diversity” as a hallmark of what can kill a successful city.5 Such homogenization posed a threat to what Kevin Lynch refers to as “imageability,” the capacity for a city to render a coherent image of its structure for those who navigate its spaces.6 But the similarities across North America’s modernizing cities were gold to Hollywood filmmakers who wanted to shoot on the cheap up north while convincing their audience otherwise. Generic urbanity makes for easy substitution.

In the wake of influential works on urban planning by critics like Jacobs and Lynch, the WSP set out to answer questions about a city’s identity by way of extensive sound recordings, revealing what we might call its sonic imageability. The work began in Vancouver in 1972 and continued in regular intervals over the next four decades. It was therefore possible that the Groundstar crew might have crossed paths with the original WSP researchers as they taught themselves how to use portable tape recorders around campus before their official recording project began. This overlap in time also opens the possibility that Schafer and his team saw the completed Groundstar film and the presentation of their city through Hollywood sound conventions before the bulk of their Vancouver recordings were complete. There is fertile ground to consider how the representational impulses across these two fields compare to each other.

Copy of The Vancouver Soundscape LP (1973) in the World Soundscape Project tape library at SFU. Photo credit: Randolph Jordan.

The WSP began as staunch documentarists, making observational style recordings that attempted objective presentations of the city’s particularities. Their first Vancouver Soundscape publication (1973) consisted of a double LP and accompanying book in which they presented raw recordings of environments they considered to be indicative of the city, gently edited into sequences that carry listeners through different quarters. But the team skewed heavily toward the musician/composer side of the sonic research spectrum, and over the years their compositional instincts began to shape the way they presented their recordings for official release. Their second Vancouver-focused release, Soundscape Vancouver 1996, contained a selection of compositions that were the result of inviting composers working in the tradition of electroacoustic music to offer their interpretations of the recordings in the archive. One can muse about the possible influence of Vancouver’s bloom into a major filmmaking center in the years between those two releases, augmenting the WSP’s interest in reshaping their city rather than simply representing it. There is a provocative tension between the representational modes at work in Hollywood films that want to simultaneously exploit and disguise the identity of their foreign locations, and the WSP’s interest in promoting locational specificity, albeit through the compositional potential of their documentary recordings.

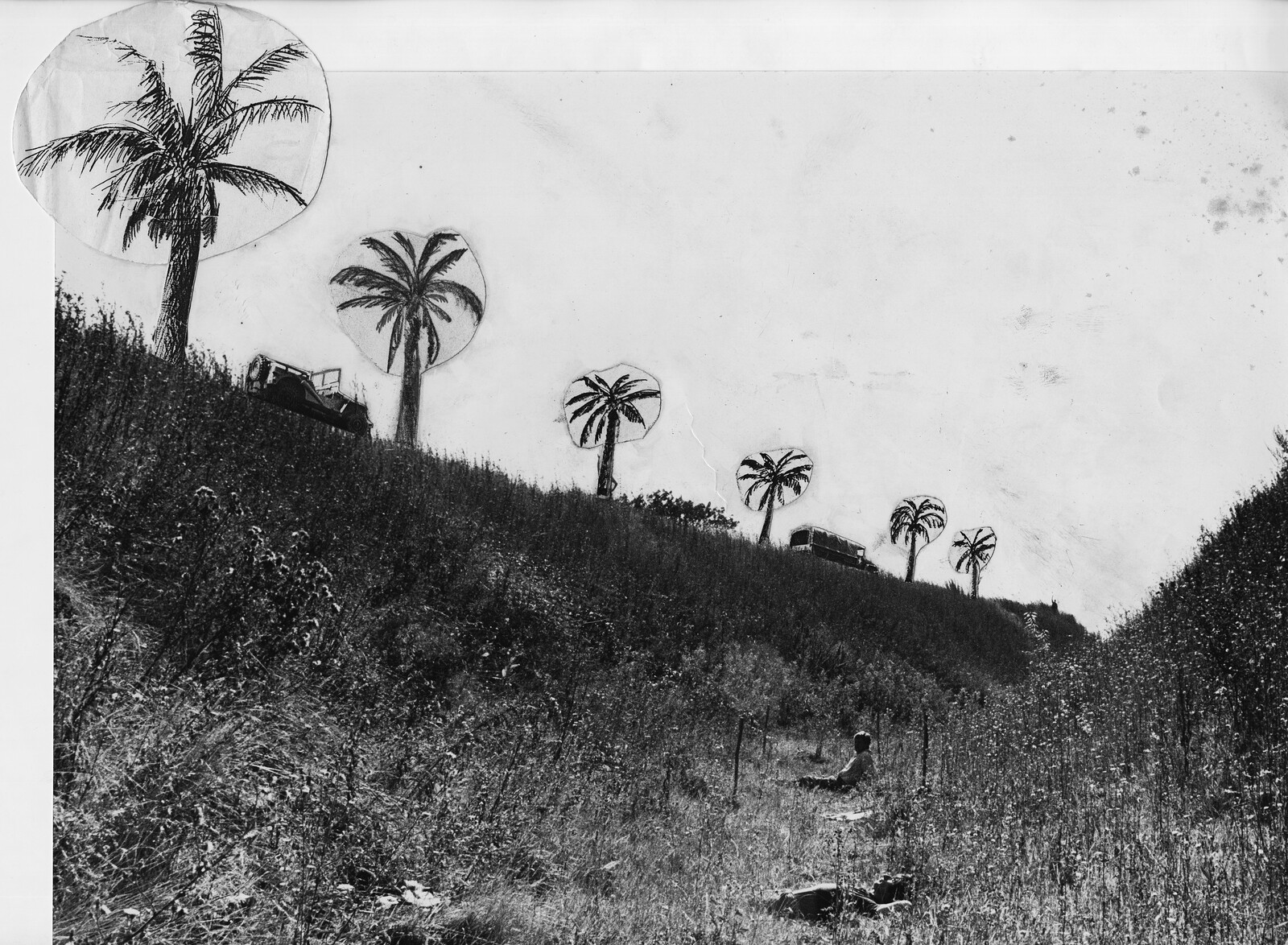

Still from The Groundstar Conspiracy (1972).

In their presentation of the SFU campus, the filmmakers of The Groundstar Conspiracy revel in the visual dynamics of Erickson’s design, going out of their way to frame the building in continually inventive ways. In one scene, for instance, a high-level government investigator named Tuxan (George Peppard) arrives at the facility to meet with project-head Frank Gossage (Tim O’Connor). Before going inside, Tuxan converses with a colleague next to the pond at the center of the Academic Quadrangle, with the extreme horizontality of the CinemaScope frame accenting the lines of the building’s structure. The dubbed dialogue is unnaturally clear and dry amidst sounds of a light breeze and trickling water. Tuxan then enters the building to meet with Gossage, whose office spaces sit right next to the pond with wall-length windows that offer broad views out into the courtyard. Gossage hands Tuxan his phone and asks if he can hear anything strange. The visual plane is open to the outside, but the sonic environment tells us we are inside: as we listen to Tuxan listening, the water is inaudible, but hushed background office noises like typing can clearly be heard.

Still from The Groundstar Conspiracy (1972).

Still from The Groundstar Conspiracy (1972).

Still from The Groundstar Conspiracy (1972).

Still from The Groundstar Conspiracy (1972).

The shot-reverse shot construction of this scene bounces us back and forth between views that are framed through multiple panes of glass in deep space, but we hear only what is directly in front of us. Gossage asks for confirmation that his phone has been tapped. Tuxan all but admits that this was done by his orders, asserting that he is now in charge of the Groundstar project while the investigation persists. Built into the narrative, then, are concerns over surveillance that are mirrored by the visually open design of Erickson’s modernist use of glass, while also commenting on the sonic containment and expectations for privacy within their enclosed spaces.

The paradox of glass in real-world physical spaces is that it is visually transparent and sonically opaque. Schafer was critical of these modernist architectural environments, describing them as “glazed soundscapes.” “Plate glass shattered the sensorium,” Schafer writes, and “[replaced] it with contradictory visual and aural impressions.” “Framing external events in an unnatural phantom-like ‘silence’ … craves reorchestration” to make these spaces “more sensorally [sic] complete.”7 Reorchestration often comes in the form of piped-in sound, creating a contradiction between inside and outside that Schafer likened to the artificiality of film: “The world seen through the window is like the world of a movie set with the radio as soundtrack.”8

For the materiality of glass to disappear, however, the frame of the window has to be deemphasized, which Ann Friedberg identifies as the modernist project of “dematerialization” in expanding the size of glass panes used for construction.9 These effects are at their peak, Friedberg says, “in the paradigmatic modernist ‘glass box’” in which windows give way to transparent walls, such as Gossage’s office.10 Here the window frame is expanded, diverting attention away from itself to create a greater sense of transparency, while containing and keeping the other senses intact. And these “dematerialized” visual spaces come with highly materialized acoustics. As Emily Thompson notes, “Walls of expansive glass and hard, thin plaster partitions resulted in uncomfortably reverberant spaces that easily transmitted sound.”11 The visually appealing design of modernist glass enclosures have to be rendered sonically acceptable through supplementary acoustical treatments that effectively banish reverberation, leaving a quiet and direct sound. These spaces contain sound, isolate it from the context of its surroundings, and as such, make the perfect vessels for filling in with electroacoustically transmitted material.12 But for Schafer, this situation was audibly distasteful. “Beautiful view—but awful sound.”13

Gossage’s office, with its border to the outside visually dematerialized, remains quiet enough to listen for minute details in the sound being piped in through his telephone. In moments like these, Groundstar highlights some key aspects of the WSP’s very own working environment, their real-world offices located not far from where Gossage’s office was shot. Schafer’s equation of glazed soundscapes with the contrivance of movie sets speaks volumes about the biases that informed the WSP’s attention to sonic environments: that filmmakers and architects alike make pretty objects that force human beings into a fragmented state of spatial experience, blank slates that must be filled in artificially. The WSP were particularly critical of two manifestations of piped-in sound: Muzak and other intentional electroacoustical reorchestrations, and the amplification of unintentional sounds that were the byproducts of isolationist design like ventilation systems, necessary for natural air circulation due to inoperable windows.14 Though the WSP did not record much on campus in their initial documentation, a tour of the SFU library was framed with close-up recordings of ventilation ports.15 Such recurring and unwanted sounds were featured in additional recordings from across the city as a demonstration of the increasing threat to the ideal “hi-fi soundscape,” which privileges a high signal-to-noise ratio that allows one to hear far into the distance.16

WSP members Bruce Davis and Peter Huse making sound recordings on SFU campus near a ventilation shaft in 1972. Photo credit: World Soundscape Project

The WSP was transparent in its distaste for such lo-fi masking sounds of the modern city, a sentiment actually shared by Hollywood, as this aspect of local soundscapes is the first thing to get dumped in a narrative film. When we listen to the SFU campus in Groundstar, we hear little evidence of the sonic byproducts of urbanization or other realities of location: whether outside or inside, background sound is kept to a minimum so as to privilege maximum dialogue intelligibility and not impede verbal communication. While the difference between the interior and exterior of Gossage’s office is denoted by a shift in the kind of background sounds present—water outside and typing inside—the treatment of these sounds in the mix is identical. In this sense, the convention of dialog intelligibility is an auditory equivalent to the visual continuum between inside and out.

There, however, is a difference in staging across the WSP’s documentation of these unwanted sounds and their banishment from Hollywood films. The former doesn’t like lo-fi situations, but is committed to documenting their existence as evidence of the need for better acoustic design; the latter doesn’t like lo-fi situations either, but they are not bound to accuracy in their representation of place, picking and choosing what stays and what goes in any bit of location recording. The tension, then, lies in the difference between the representational practices of documentary and fiction. But underlying this tension there is agreement in their shared desire for hi-fi soundscapes. The WSP hoped for architects and urban planners to solve the problem of lo-fi spaces through better practices in acoustic design, while filmmakers were free to design the acoustics of their onscreen spaces as they saw fit. Eventually, the WSP would embrace their own capacity for the creative rendering of real-world space through the art of soundscape composition, but they differed in one important way from their Hollywood counterparts. Their interest in reshaping the world in front of their microphones was never put in the service of disguise: they wanted their creative treatments of actuality to open space for the contemplation of locational identity.

The ideological commonalities and tensions between WSP practices and Hollywood film conventions became the guiding premise for my work as sound designer on the Impostor Cities project. Blending documentary sound recordings made on sites like the SFU campus with the fictionalized soundscapes designed for the films in which they appear, I aimed to reflect the ways in which both Hollywood and the WSP highlight the city’s distinctive features while reshaping those features to suit their own ends. When I visited the SFU campus in December 2019, during the winter holiday, the courtyard of the Academic Quadrangle was barren, but the ventilation shafts were blowing deep and loud. I stood with my recording equipment close to where Tuxan stood, next to the pond outside Gossage’s offices. In this central position, in the middle of the Quadrangle, there was a reflective quality created by the surrounding surfaces that blended the ventilation with other environmental sounds, particularly the calls of crows flying, their voices echoing in response to each other as well as off the walls of the building.

Ambisonic microphone used by the author to make sound recordings on SFU campus in 2019. Photo Credit: Randolph Jordan.

The Quadrangle functioned like a multichannel mixing console, gathering all sounds in the environment, layering them over one another while assigning trajectories of reverberant movement through the space, all against the backdrop of the rumbling ventilation system. This recorded environment, captured with an ambisonic microphone to deploy into a multi-channel array, was then used as the base layer for the soundtrack that accompanies the SFU sequence in the exhibition featuring scenes from Groundstar along with other productions that have been filmed there like Battlestar Galactica (2004–2009), and Stargate SG-1 (1997–2007). Across the SFU sequence, features of the sonic treatments of this space as presented in these films are mixed in to offset the location-specific realism of my own recordings. In this way, the language of Hollywood’s sonic fabrication reveals the mediation at play in their spatial representations and exposes the tension between simultaneously exploiting a particular location for its existing qualities and advocating for their disappearance.

Still from a draft version of the four-screen layout for the Impostor Cities exhibition (2021).

The duality in this sonic representation of real-world spaces mirrors the duality with which these spaces are treated in films. At the heart of the relationship between disguise and revelation is the issue of imageability: to what extent do the appearances of highly distinctive architectural sites connect with the mental image that people have of real-world spaces? And on a broader scale, how do all of these Canadian sites function within the imageability of the nation as a whole? One recurring motif built into the sound design explicitly references the exhibition’s theme of the fragmentation of Canadian identity across global screens: renditions of “Oh Canada” that weave in and out of the mix across locations in various forms, sometimes melodically legible, other times deconstructed. It appears in the form of air horns atop the BC Hydro building in Vancouver, as a music box programmed with the tune but turned slowly enough to challenge recognition, and as bells tuned to the correct pitches but presented out of sequence. This continual reshaping of the national anthem calls attention to the fluctuating imageability of the country’s architectural identity, sometimes imposing a fragmentary experience, and at other times reinforcing a sense of unity. This treatment functions as a fractalized unit of the broader combination of documentary and fictionalized sounds and capitalizes on the exhibition space as a glazed environment, within which screens emulate a series of windows framing views out onto the Canadian architectural landscape while preventing physical passage, and whose interior is filled in with electroacoustic treatments that reorchestrate our understanding of that landscape from afar.

Amidst this swirling interplay of materials, the audience is put in the position of Bellamy confronting Tuxan in The Groundstar Conspiracy, a conversation that might be interpreted as Canada confronting Hollywood, or perhaps the WSP confronting post-war urban planners. “When you can take a man’s identity,” Bellamy says, “his face, his mind, his memory, and use it for something you consider more important, that scares me. Nothing scares me more except the willingness to let you do it.” Canadians are complicit in the erasure of our identity on the world stage, but Tuxan reminds us of the upside of this: “You’ve got something nobody in the world has: a chance to start over, clean, fresh.” The sonic juxtapositions of the Impostor Cities exhibition suggest Canada as a blank slate awaiting its next disguise, with Hollywood filmmakers already seeking out the audible glaze that coats architectural sites for their imageability. Yet we can’t escape the knowledge that, somewhere underneath the veneer of each overwriting pass, there lie truths that we must hold onto.

Sarah Matheson, “Projecting Placelessness: Industrial Television and the ‘Authentic’ Canadian City,” Contracting Out Hollywood: Runaway Productions and Foreign Location Shooting (Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005), 117-139, 113.

This essay is revised and expanded from material first presented at the Music and the Moving Image conference at NYU in 2021 and in the conclusion to my book Acoustic Profiles: A Sound Ecology of the Cinema (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023).

For a comprehensive historical overview of the work of the WSP, see the timeline in Sound, Media, Ecology edited by Milena Droumeva and Randolph Jordan (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

R. Murray Schafer, The Book of Noise (Wellington: Price Milburn and Co., 1970), 2.

Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Vintage Books, 1961/1992), 241.

Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1960), 9.

R. Murray Schafer, Voices of Tyranny, Temples of Silence (Indian River: Arcana Editions, 1993), 71–73.

Ibid., 73.

Anne Friedberg, The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 117.

Ibid.

Emily Thompson, The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in North America, 1900–1933 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002), 209.

Ibid., 228.

Originally in French as “Bellevue, mais mauvais son.” R. Murray Schafer, The Tuning of the World (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1977), 222.

Here we find a measure of sonic homogeneity to match the borderless feeling between inside and out afforded by the transparent walls: whether inside or out, the steady flow of moving air through ventilation shafts is always nearby.

Notes on these recordings are available here, ➝.

Schafer, The Tuning of the World, 43.

Impostor Cities is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and The Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto within the context of its eponymous exhibition, which was initially commissioned by the Canada Council for the Arts for the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale.