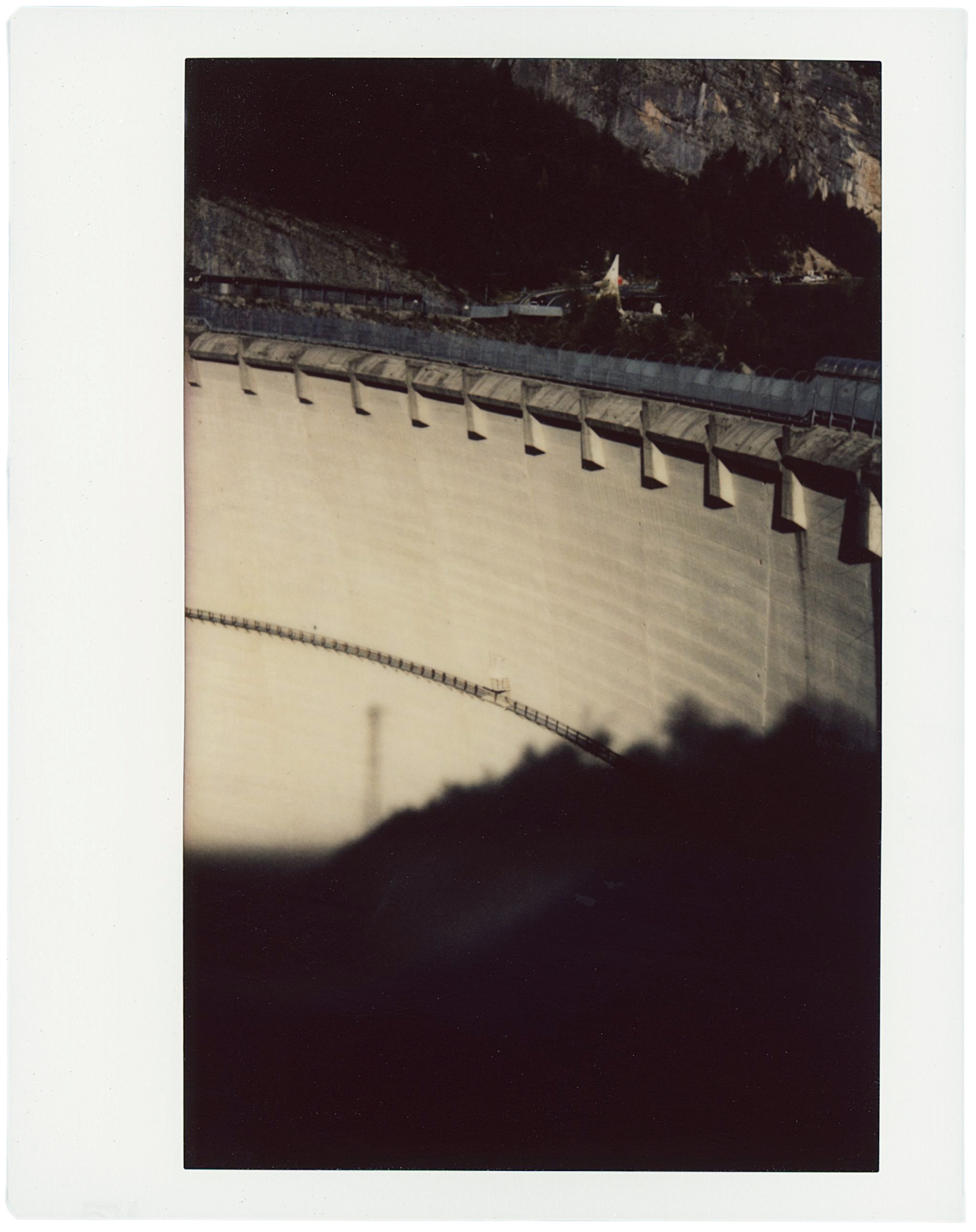

The construction of the Santa Clara dam (1963–73) on the Mira River created a 12,000-hectare “irrigation perimeter” for hydro-agricultural exploitation along a 41-kilometer strip of Portuguese coast in the southwest of Alentejo, between Vila Nova de Milfontes and the village of Rogil. Located within the Vicentine Coast Natural Park, water within this zone is controlled upstream and distributed by a low-energy gravitational system. Given that water, once diverted, cannot flow back, the system requires careful monitoring of the water that goes into the general distribution channel. In line with the flow of the water, irrigation of various points in the network takes place according to a stipulated timetable: some points earlier, others later.

It is this water that supplies the “pluriurban areas” around the municipalities of Odemira and Aljezur. The water is used for domestic consumption, small-scale horticultural production, and extensive summer plantations of sweet potatoes and peanuts. These activities also occur in more “precarious areas,” lands outside the irrigation zone that rely on water from the same reservoir. The management of this water supply system falls under the aegis of the Mira Beneficiaries Association (Associação dos Beneficiários do Mira, or ABM), which is made up of representatives from different “beneficiaries” and supervised by the Ministry of Agriculture. This model, which was first established in the 1970s, remained more or less stable until 2017, when Driscoll’s, the world’s largest producer of soft fruits, expanded its 30-hectare holding, first established in 2004, to 1,000 hectares. Together with other horticultural and flower businesses, the ultra-intensive agroindustry today covers a total of some 3,000 hectares in the area.

Agroindustry companies operating within the irrigation perimeter of the Mira River benefit from packages of “fiscal incentives” on top of the turnover they generate. When they set up new production units, they can usually count on the support of the current prime minister, whose manifesto guarantees state support for this production model. As a result, representatives of the agroindustry have come to control the ABM. Their crops have substantial water needs throughout the year, which have led them to substantially reduce the share of water allocated to small-scale farmers. In 2023, the ABM exacerbated the existing conflict between traditional farmers and the “beneficiaries” of agroindustry by trying to exclude “precarious areas” from receiving water. As a result, and in an attempt to assuage the social tension in the area, the Ministry of Agriculture replaced the ABM management.1

Because the region has cyclical droughts and scarce water supplies, Alentejo has always recorded the lowest water consumption in the country. It has historically been sustained by dry farming, the frugal use of water for irrigation, and the selection of seed stocks adapted to dry conditions. Traditional farmers in the region therefore have a perspective on drought, climate change, and water scarcity that differs from that of both the government and the media. These farmers once supplied Lisbon with vegetables and dried fruit for export. Yet there has never been such a wide area under cultivation as there is today, nor has so much water ever been consumed. In 2023, summer wildfires consumed a 9,000-hectare area of houses, forests, and agricultural plots around the municipalities of Odermira and Aljezur. Only after this did the government, under pressure from business, local merchants, cooperatives, and local authorities, overturn its 2017 decision to authorize the expansion of the irrigation zone from 3,000 to 5,000 hectares.

Traditional societies, environmental awareness, and agribusiness

There is no diplomatic resolution for the tension between traditional societies and the socio-environmental complex of agribusiness.2 On the one hand, hegemonic techno-capitalism evades dialogue with other modes of understanding and acting in the world, revealing a seemingly unlimited capacity to absorb and manipulate foci of resistance. On the other, local populations are often unable to perceive processes whose causes and aims are not themselves local. In the case of the soft fruit business, water and soil are the only local factors of production. The rest are, in the words of Paulo Barriga,

Wholly imported under the strict provisions of the respective patents, from the plants and irrigation systems, through the metal and plastic frames used in the polytunnels, to the fertilizers and even the substrate where the raspberry bushes grow … to the agronomic methods, the fruit picking, the packaging … to the marketing of the product which fixes the market price.3

In other words, the entire machinery of this new, irrigated agriculture is shielded from local reality and in constant flux. Furthermore, the product of this labor is immediately exported (95% of the produce goes directly to markets in England, Germany, and Scandinavia) and the labor force is imported, mostly from Asia. Only the ground remains stable. Although the raspberries are not cultivated in the soil but, rather, hydroponically, their occupation of the land and their use of water breed anxiety.

Before the expansion of ultra-intensive agriculture around 2007, there had already been a marked change in the social make-up of the region. In the last two decades of the twentieth century, an impressive diversity of people from urban communities around Portugal, as well as northern and central Europe, settled in the area. The restrictive construction policies of the natural park have largely left the Alentejan Southwest out of the circuit of mass tourism. As a result, the coastal area has gained the status of one of the best-preserved coastlines in southern Europe. This, in turn, has brought about an increase in so-called “nature tourism,” which has been driven largely by new residents.

The relationships that have emerged between these new residents and local populations have brought changes to the territory. Apart from an appreciation of local products and the landscape through outdoor activities such as surfing, hiking, and cycling, new agroecological and permaculture projects have been developed that call on traditional agricultural knowledge and are rooted in a scrupulous respect for one’s surroundings, a perceptive understanding of place, reading the cycles of the earth and crops, and selecting seeds that are well adapted to the local ecosystem.

This development has empowered traditional agriculture in the face of a more industrial one that, sustained by chemical and mechanical processes, rejects traditional practices as outdated and civilizationally backward. According to Manuela Carneiro da Cunha and Mauro W. Almeida, “the surprising change of ideological course” for traditional agriculture and its advocates, from laggards to the forefront of modernization and the guardians of the future, is accompanied by other conceptual changes.4 The categories of “ecosystem” and “earth,” so central to the corpus of biology, geology, and Earth sciences, here take on a political dimension. Knowing as we do that the system of mass production acts as a geological force, the Anthropocene calls into question not only our way of life, but the architecture of scientific knowledge that is based on the separation of natural and social sciences. The separation of nature and culture, and the idea of politics as centered solely on human power relations and decision-making processes, is no longer sustainable.

In 2009, activists in Alentejo, together with the local populace, created the Juntos pelo Sudoeste (“Together for the Southwest”) movement to fight against the uncontrolled advance of extractive and intensive farming in the natural park, as well as against the construction of a desalination plant that industrial agribusinesses were demanding and the state was considering. The current irrigation system of the Mira is bolstered by a number of more or less illegal boreholes that pump water from the water table, but that cannot keep up with the exponential growth of business. With the desalination plant, the agroindustry sought to circumvent the perverse effects of its intensive practices, and render its destructive consequences productive.

This way of acting stems from the belief that a techno-economic mutation generated by the system itself will not only save us from ecological collapse, but will generate an ecopolitical order of material abundance.5 The argument for a substantial reduction in the area of industrial farming, for a slowdown in both consumption and economic growth, for a life less artificial—for a life rooted in the inextricable connection between human and non-human life—all of which are made by the activists of Juntos pelo Sudoeste, is the greatest ideological enemy of these agribuisnesses. Meanwhile, conditions on the ground show signs of changing even faster than technical superstructures or Earth’s regenerative capacity. In the words of Deborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro:

The willful acceleration of the capitalist machine posited as the solution to our present anthropological misery finds itself in a position of objective contradiction to a wholly unintentional response, the relentless process of environmental transformations. … There are serious grounds for fearing that a globalized post-capitalism will not arrive quickly enough to avert the slow collapse of the planet’s ecology.6

Carlos Dias, “Guerra pelo acesso à água intensifica-se no perímetro de rega do Mira,” Publico, July 8, 2023. See ➝.

The expression “traditional societies” does not mean adherence to a tradition, which is contradictory to current anthropological knowledge, but refers to the environmental impact of the ways of life of small rural communities whose agricultural and ecological knowledge is based on a detailed understanding of the place, as opposed to the model of industrial agricultural production generated by the explosion of the chemical and petroleum industries triggered by two world wars.

Paulo Barriga, “No mundo secreto das estufas (In the secret world of polytunnels)” Sábado, July 13, 2021.

Manuela Carneiro da Cunha and Mauro W. Almeida, “Populações tradicionais e conservação ambiental (Traditional Populations and environmental conservation),” Cultura com aspas e outros ensaios (2009).

On the different expressions of accelerationism and technological genius see: Deborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Há mundo por vir? Ensaio sobre os medos e os fins (Lisbon: Antígona, 2023).

Danowski and Viveiros de Castro, Há mundo por vir?, 117.

Hydroreflexivity is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and “Fertile Futures,” the Portuguese Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia curated by Andreia Garcia with Ana Neiva and Diogo Aguiar.

Category

Subject

Translated by Russell Shackleford.