Draining the Marshes

In the mid-1970s, a forty-five-minute-long documentary film by Kassem Hawal titled Al-Ahwar (The Marshes) presented a window into the multifaceted existence and vitality of the Ahwari people residing in the Mesopotamian marshes. Nestled within the impoverished southern Iraq between the cities Nasiriyah and Basrah, this wetland expanse provided the backdrop for a portrayal of diverse aspects of Ahwari life, from the roles and experiences of women and social relationships to modes of production and construction, healthcare, and education. The film culminates in footage capturing the exuberance of a wedding celebration aboard a sailing boat. The film was widely screened in theaters in Iraq and across the Arab world until an abrupt stop in 1991.

In March 1991, an unprecedented civil uprising against Saddam’s ruling Ba’ath party regime erupted across the country. It followed the devastating eight-year war with Iran, and only a month since Iraq invaded Kuwait, both of which left the nation ravaged. This was the only nation-wide uprising that occurred during the thirty-five-year dictatorial rule by the Ba’ath party led by Saddam Hussein (1979–2003), and was the largest insurrection in the region until the Arab Spring in 2010. The rebellion first ignited in south of Iraq before radiating outward, gradually spreading across most of the country. Iraqi military forces were immediately deployed to reclaim cities. To seek refuge, Shi’a revolutionaries hid in the southern marshes and Kurdish revolutionaries hid in the northern mountains. Although the environment of the southern wetlands is vastly different from the northern mountain environment, they both stood as natural defensive perimeters, out of the state’s reach. The resistance in the north succeeded in demarcating a Kurdish autonomous zone. However, the resistance elsewhere across the country was brutally suppressed.

The aftermath of the 1991 uprising saw the marshes and their inhabitants subjected to a form of retaliation for their disloyalty that was different than other parts of the country. After all, not only did the marsh environment offer the ideal hideaway, but the indigenous inhabitants of the marshes actively contributed to the uprising, aligning themselves with the forces of the revolution. Rooted in a longstanding history of providing refuge to those oppressed by or who oppose authority—from slaves during the Abbasids rule to factions within the communist party in the sixties—Ahwari people also contested the state and fiercely defended their autonomous modes of existence, one that is intricately intertwined with the marsh environment.1 Far more than mere zones of ecological and cultural richness or biological diversity, the Iraqi wetlands are a complex arena where political agency is articulated and enacted; a space where power is both challenged and reproduced. The unique qualities of the marshes attract attention and aggression, regardless of the regime that holds power in the region.

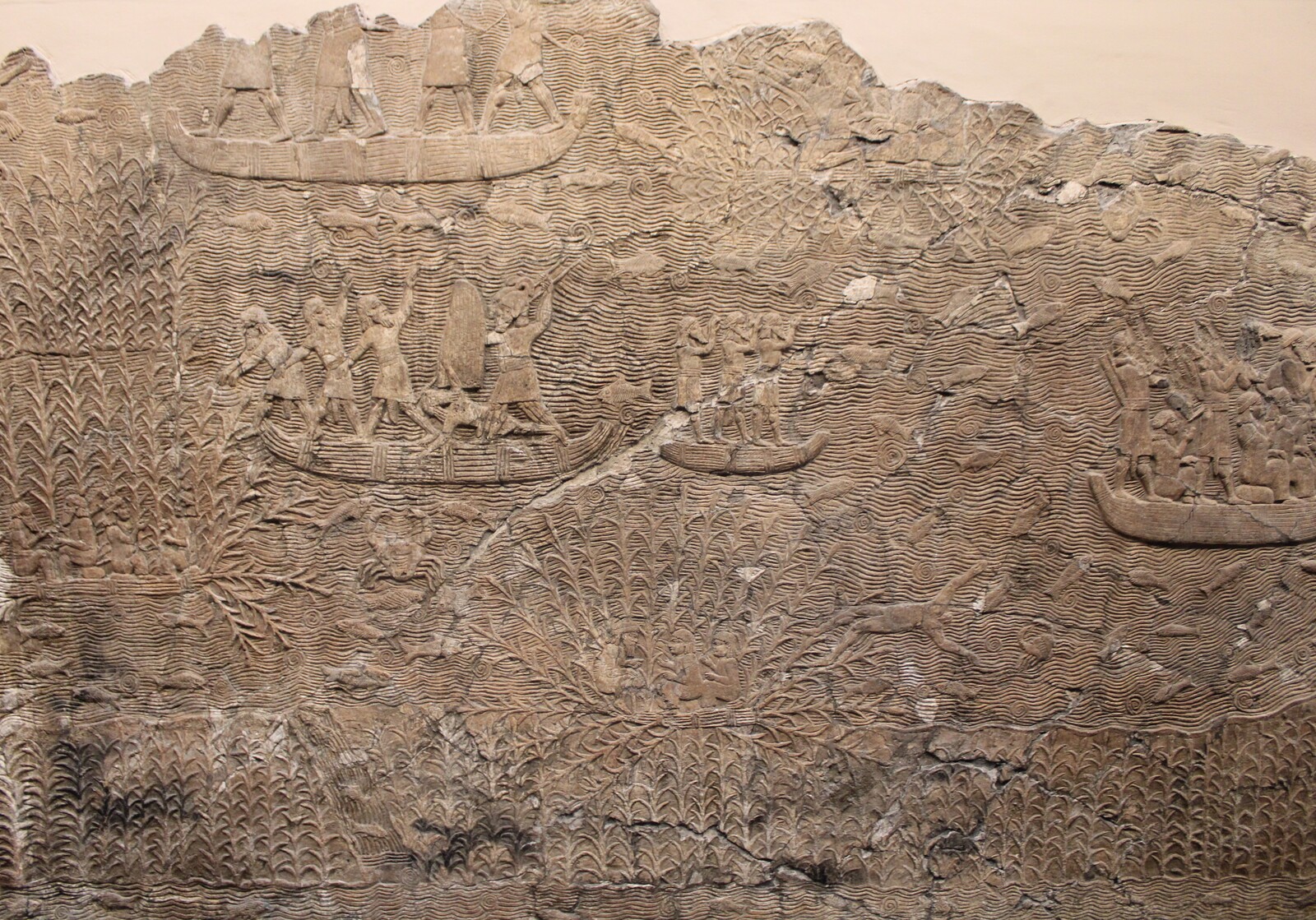

Still from Kassem Hawal, Al-Ahwar (1976). Courtesy of Kassem Hawal and the author.

Still from Kassem Hawal, Al-Ahwar (1976). Courtesy of Kassem Hawal and the author.

Still from Kassem Hawal, Al-Ahwar (1976). Courtesy of Kassem Hawal and the author.

Still from Kassem Hawal, Al-Ahwar (1976). Courtesy of Kassem Hawal and the author.

Still from Kassem Hawal, Al-Ahwar (1976). Courtesy of Kassem Hawal and the author.

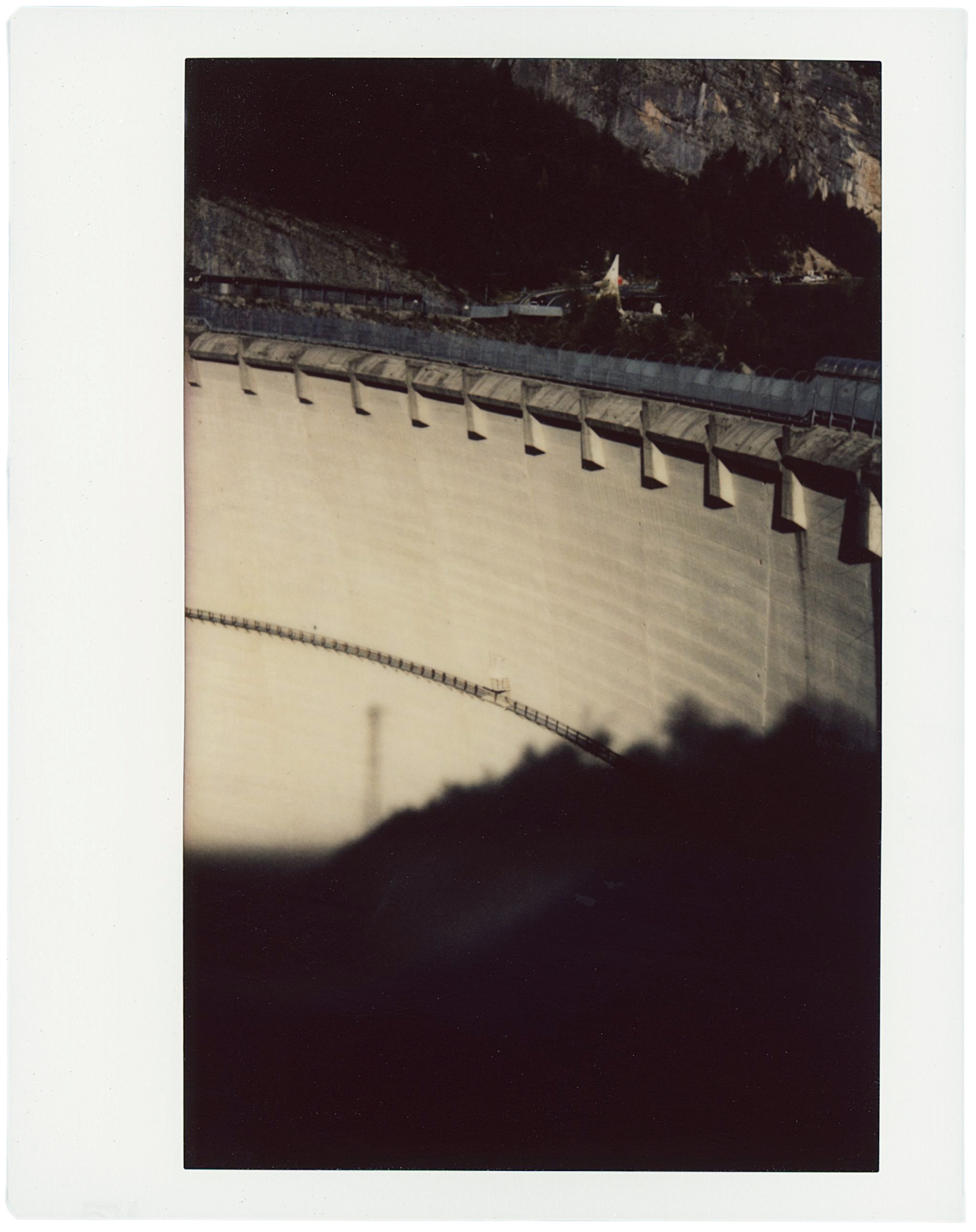

As a response to the uprising, the military electrocuted the water of the marshes, contaminated them with toxic chemicals, burned villages, and blasted the armories spread throughout with depleted uranium, exposing the inhabitants to radiation. In 1993, Explosive Ordinance Disposal (EOD) officials carried out a demolition operation in the marsh villages which resulted in the formation of a massive mushroom cloud, the effects of which continue to have a devastating impact on the health of current and future generations.2 However, to eliminate the breeding ground and waters of resistance, the entire ecosystem was transformed. Despite the fact that Iraq was grappling at the time with crippling sanctions imposed by the United Nations Security Council, a closure of Iraqi airspace, and the aftermath of the Iran and the Gulf war, Saddam ordered the construction of extensive, large-scale, advanced water engineering projects to drain the marshes. Various techniques were deployed to desiccate the marshes once and for all, such as flooding, diverting, evaporating, and blocking water. This involved the construction of dams, canals, sluices, barrages, polders, causeways, artificial lakes, rivers, dikes, and embankments. These infrastructures were justified by the government under the rhetoric of encouraging the economic, social, and cultural revival of the area, all the while giving these developments names that emphasized the state’s victory in repressing the uprising, like “AlQadisia” River (which references a historic battle in which Arabs won over Persians), “Mother of the Battle” River, “Fidelity to the Leader” River, “Crown of the Battle” River, “Glory” River, and “Saddam” River.

Within only two or three years, ninety percent of the marshes were drained.3 The remaining ten percent only survived because the marsh was partially under Iranian state control. The drainage resulted in mass human displacement, the loss of the area’s unique environmental biodiversity, and with it, the lives of countless species of plants, fish, animals, and birds.

Alongside these projects to drain the marshes, in 1991, following the uprising, the Iraqi minister of foreign affairs Tariq Aziz ordered every copy—both positive and negative—of “The Marshes” to be burned.4 Hawal’s film stood as evidence to both the ecocide and genocide that took place in the marshes. Alongside this film, every cultural resource on the marshes was banned or destroyed. The only other copy Hawal stored outside Iraq was in Beirut, which had been previously stolen in 1982 by Israeli forces during their occupation of Lebanon. As Hawal mentions, the film was then transported to Israel and stored in the archives of Israel’s ministry of defense.5

Inhabiting Wetlands

Dating back nearly 6,500 years, the Mesopotamian marshes are one of the largest ecosystems of their kind in Eurasia. They have a direct relationship with the mountains in the north, relying on seasonal snowmelt in Turkey and Iran, and downstream floodwaters through the Tigris, Euphrates, Karkheh, and Karun rivers. By taking in excess water, the marshes function as a natural flood management system. Its three main marshes once covered an area of approximately 20,000 square kilometers, consisting of swampy terrains, waterways, lagoons, reed beds, waterfowls, wildlife, and for thousands of years, the homes of its human inhabitants, the Ahwari people. Within this environment, Ahwari people practice their distinct culture and traditions involving water mobility, production, farming, animal husbandry, politics, and social relations, which as a result of being located on water, are all spatially articulated and designed.

Building an archipelago of artificial islands of floating reedbeds requires a deliberate set of design decisions. The unique, intricately articulated spatial configuration of daily life allows for gender, familial, and societal relations to become unbound by the limitations of modern spatial definitions and divisions. Within each village, each family dwelling is built on a separate floating reedbed. The dwelling’s only sheltered spaces are those designated for resting, hosting, or housing livestock, each of which have a separate detached structure. Hosting, for example, is an integral part of their social and tribal activities and takes place in a dedicated structure called the Mudhif, which serves as a guesthouse and for ceremonial occasions such as births, weddings, funerals, or other important meetings. It is built with far more intricate construction techniques than other structures in the village, and each Mudhif often represents a particular tribe. The building is constructed collaboratively amongst members of the community with woven and bent reeds. Buildings are expanded every few years if not demolished and rebuilt due to the fragile nature of reed. Most other activities are predominantly performed by Ahwari women, from baking and dairy making to cultivating, fishing, animal husbandry, reed cutting, and weaving, all of which take place mostly outdoors on the floating reedbed or on boats in the water.

Mudhif (guesthouse), Hammar Marsh, Iraq. Photo: Ameneh Solati, 2022.

Interior of a Mudhif (guesthouse), al-Chibayish, Iraq. Photo: Ameneh Solati, 2022.

Interior of a marsh dwelling, Hammar Marsh, Iraq. Photo: Ameneh Solati, 2022.

Ceiling of a marsh dwelling, Hammar Marsh, Iraq. Photo: Ameneh Solati, 2022.

Mudhif (guesthouse), Hammar Marsh, Iraq. Photo: Ameneh Solati, 2022.

The Ahwari people’s reliance on a remote wet environment is not coincidence. To build on water and limiting movement to water-based vehicles is a strategic decision to protect the villages from aggressors’ access and movement, and therefore provide a degree of independence and autonomy. The seasonally changing water bodies dotted by villages of floating reedbeds and extensive mazes of reed-lined waterways and swampy lands produce an illegible and unmappable condition. In defying conventional cartographic logics, the marshes are rendered as an impenetrable terrain. The Ahwari people are acutely aware of these unique conditions, and gain the skills that are essential for inhabiting and navigating the marshes from childhood through orally codified ancestral knowledge. Living in a challenging environment is an act of ethnic, cultural, and self-determination.

Taming the Waters, Taming the People

The Ba’ath regime was not the first ruling power to target the marshes and its inhabitants, nor was the aftermath of the 1991 uprising its first attempt to gain control over the area. From Sumerian to Ottoman and British rule, records recount military campaigns dispatched to the marshes to attack “outlaws.” One of the main reason for this could stem from the economic wealth to be gained by extracting the oil that lies underneath some of the marshes, exemplifying the colonial logic that renders a natural environment as terra nulliu to justify its occupation and exploitation. In fact, contrary to Saddam’s typically nationalist and Arab-supremacy ideologies, his plans for draining the marshes were inspired by designs dating back to the 1950’s under the British mandate in Iraq drawn up by British engineers for the British-controlled Iraq Petroleum company to facilitate infrastructural developments.6 The British authorities then were aware that a multi-ethnic region such as south of Iraq would prove difficult to govern, even a threat to sovereignty if not eliminated or divided. The marshes, after all, are neither a homogenous natural environment that could be simply exploited, nor an uninhabited territory that could be easily absorbed into systems of governance. However, the threat of autonomy, resistance, and self-sufficiency of the marsh inhabitants triggered an unprecedented aggression by the Ba’ath party regime far exceeding any strategies necessary to extract oil.

The 1991 drainage projects were predated by earlier campaigns of spatial reform that started once the Ba’ath party came to power in 1968, and notably intensified during the war that Iraq instigated with Iran in 1980, whose damage was concentrated in the south of Iraq.7 The eastern-most marsh, Al Hawizeh, not only overlaps with one of the biggest and richest oil deposits in Iraq, but is also bisected by the Iranian border. As the position of the marsh and its treacherous environment was a point of vulnerability for national security, Saddam started recommending in the 1980s constructing new petrol stations, police barracks, electrical grid connections, irrigation projects to enforce modern agricultural techniques, land surveying and leveling, and paving roads. Modernist technopolitics such as these laid the groundwork for the more radical drainage projects that occurred in 1991, all of which were done in the hope that a more “familiar” dry environment would encourage the water-roaming marsh-dwellers to finally become sedentary, and their movements more predictable.8

Barbarism and Resistance

Historically, the birth of the state coupled with the spread of western notions of civilization and progress helped create both material and subjective distinctions and divisions between different geographies and environments globally. As a consequence, the very concept of law became synonymous with morality, with spaces where the tentacles of state authority exert minimal or no control relegated as lawless and by extension immoral. By applying this logic to either the mountains, forest, ocean, desert or the wetlands, the inherent wildness of the natural environment is extended to its inhabitants, branding them as barbarians. Among these environments, the swampy marshes are one of the lowest on the scale of supposed civility. As James C. Scott argues: “Once we entertain the possibility that the ‘barbarians’ are not just ‘there’ as a residue but may well have chosen their location, their subsistence practices, and their social structure to maintain their autonomy, the standard civilizational story of social evolution collapses.”9 The Mesopotamian marshes is one of many such ecologies that challenge the reductive conceptions of the natural world and those who inhabit it. They offer alternative understandings and disrupt established hierarchies between humans and their surroundings.

Throughout history and to this day, Ahwari practices of resistance and autonomy are perceived as barbaric or uncivil, and often in relation to law, either rebelling against or hiding from it. This logic serves to dehumanize and demoralize the Ahwari people. However, the unique environment of the marshes generates modes of living that defy state hegemony. It has fostered an ecology that values the relationships between nature, humans, and non-humans, and allows the Ahwari people to maintain tribal social structures based on kinship and self-governance. This posed a threat to the Iraqi citizen’s identity that the Ba’ath regime sought to define as part of its nation-building project. Therefore, since the start of the regime’s rule, approaches towards the marshes were always based on two strategies: transforming the environment to influence the subject, and influencing the subject to resettle to a desired environment. Aggressive methods were applied in 1989 such as economic blockades, withdrawing food supply agencies, and banning the sale of fish.10 At the same time, they sought to discipline the Ahwari people into the ideal, homogenous, civil Iraqi citizens. As such, the regime set out to to transform Ahwari modes of living by introducing plans for housing, public health facilities, schools, and marketplaces, all of which were poorly developed or left unfinished. One speaker in the Iraqi parliament even suggested in a 1992 assembly that relocating marshland inhabitants to houses along the highway would make them “good citizens” by providing them with access to electricity, clean water, standardized education, and medical care—similar strategies that were deployed in displacing Kurdish population in north of Iraq.

The various historical efforts by different powers to consolidate ethnic differences in Iraqi society has left a large impact. Since the construction of one of the earliest dams in Iraq in 1939, Ahwari people have been displaced to other parts of Iraq and subjected to oppressive and discriminatory practices—from isolating them on the margins of cities dedicated mostly to ethnic minorities such as the Thawra (Sadr City) in Baghdad, to limiting their access to public services and basic human rights.11 Additionally, resettlement and displacement forced the Ahwari people to adopt new skills and modes of survival. Ahwari culture and traditions that are tied to their watery environment are rapidly eroding after decades of displacement.

The Flood

Despite extensive efforts to eradicate the marshes and its inhabitants, as soon as the government began to crumble and the United States invaded in 2003, the marshes were the first site to be liberated by its own people. They did not wait for American troops, nor for the transitional Iraqi government to welcome them back: they took matters into their own hands, breaching sand dikes and dams. With the help of neighboring tribes and some machinery and tools, they initiated the re-flooding of the marshes. Despite a ban on returning to the marshes put in place in 1991, the uncertainty of the future, and the risk of explosive mines planted en route, Ahwari people were determined to bring back the water that was essential for their return. In a few years, seventy percent of the water in the marshes returned, as did some Ahwari people, living in various proximities and relations to the marsh water.12

In 2006, Kassem Hawal received a phone call informing him that a negative of “The Marshes” was miraculously found. A few years later, the film was restored and again screened in theaters locally and internationally, only this time reminiscent of a place that used to be. The returning of both the water and the Ahwari people to the wetlands was a fleeting joy, as American and European governmental and private sector companies soon descended upon the region, eagerly investing in new oil field stations in the area. Despite the marshes being listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2016, little was done to maintain the water levels and quality in the marshes. In fact, the designation did more harm than good, limiting the freedom of the Ahwari people to sustain their particular modes of living in the face of a rapid decline in water levels, due in part to changes in rainfall patterns and humidity, rising temperatures, stronger and dryer winds, and toxic dust.

Given that the hydrology of the marshes relies on rivers that originate beyond the area or even the national borders of Iraq, the scarcity of marsh water is not just a result of climate conditions. It is also a consequence of hydropower developments in Turkey and Iran that effectively weaponize water to advance those countries’ political and economic agendas. The Tigris and Euphrates rivers, for instance, have most recently been affected by Turkish water infrastructure projects like the Ilisu Dam, which is part of the Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP) consisting of twenty-two dams and nineteen hydraulic power plants.13 In addition to devastating impacts within Turkey, including the displacement of 80,000 people, the completion of the Ilsu Dam in 2018 has also significantly reduced the hydrological flood processes of upstream flood water that the marshes rely on for its survival. Similar river-based infrastructural developments in Iraq have also altered the geographic distribution of water so that it is distributed in central Iraq for agriculture and urban use before it even reaches the marshes in the south.

Visions for the Future

The future of the marshes is a subject of much debate and speculation. Jassem al-Asadi, a native who worked for the Ministry of Water Resources for thirty years before co-founding Nature Iraq, a non-governmental organization dedicated to Iraq’s environmental health, was instrumental to virtually all research that has taken place about the marshes over the past decade.14 In his capacity as a managing director of the NGO’s Chibaish office, within the marsh region, Al-Asadi created and disseminated baseline representations of the marsh environmental conditions by surveying, monitoring, and documenting the area.15 Al-Asadi argues that the climatic challenges and water scarcity confronting the marshes, which extend beyond Iraq’s sphere of control in a region bereft of water resource agreements, render the preservation of the entire wetlands an implausible objective.16 Instead, he advocates for a pragmatic and attainable approach: the identification and designation of a specific manageable area within the marshes as a nature reserve. By directing all resources and endeavors towards protecting this demarcated zone, he hopes that water demands can be mitigated and at least one marsh area’s survival guaranteed.

Others, like Abu Haidar offer an alternative vision for the survival of the marshes. Abu Haidar is an independent Mashhoof (traditional canoe) tour guide and native to the region who returned to the marshes after the fall of the regime in 2003, choosing to establish a home on solid ground by the shores of the marshes. He argues that the only way for the marshes to survive is to develop cultural- and eco-tourism in the area.17 Highlighting the economic value of the area will, he claims, compel the government to engage more vigorously in regional water negotiations and prompt improved management and equitable distribution of water resources at a local level. Abu Haidar elaborates how the development of eco-tourisim in marshes can provide new economic opportunities for the locals, many of whom currently live beneath the poverty line: villagers could offer unique guest accommodation in their homes on floating reedbeds; fishermen could supply fresh local catch; bakers could make fresh bread; dairy farmers could milk water buffaloes and make geimar (thickened cream); weavers could fashion rugs and baskets from harvested reeds. The experience would be enriched by traditional poetry recitals, harmonized with a symphony of water, rustling reeds, croaking frogs, and melodious bird songs.

Conventional narratives in history and anthropology often treat subsistence, kinship relations, and cultural practices as fixed entities, assumed to be ecologically and culturally predetermined, and therefore easily replicable. However, these intricate environments and their corresponding ways of life are intricately woven into interconnected ecological rhythms, consistencies, and harmonies that defy simplistic recreation. While Al-Asadi’s vision leaves the fate and role of the inhabitants within a nature reserve uncertain, Abu Haidar’s leaves them reliant on tourism for their sustenance, an industry that is highly sensitive to unstable climatic and security conditions, both of which Iraq suffers from. Furthermore, tourism would both render the Ahwari people as props in an open-air museum and threaten the marsh ecology with required infrastructural developments. Both visions provoke contemplation on the ramifications of introducing novel dependencies, industries, and regulations to the marshes, and the potential impact on both the ecological system and the autonomy and self-reliance of the Ahwari people.

Echoes of Violence

In February 2023, reports emerged that Jassem al-Asadi had been abducted.18 His brother testified that Al-Asadi was forcibly removed from his car in broad daylight on the highway between Hilla and Baghdad by armed individuals masquerading as civilians who operated with military-level skills. Both the abductors and government officials remained silent for two weeks, with neither public condemnation nor demands, which caused widespread distress in the Iraqi environmental and local marsh communities. Against the backdrop of countless activist deaths both within Iraq and beyond, Al-Asadi’s fate appeared ominously grim. But finally, he was released, and immediately left Iraq to be treated for the torture he endured during captivity. Despite the threat to his life, Al-Asadi decided to return and continue his work to protect the marshes. These echoes of the 1991 uprising remind us of the inextricable relation between environmental resistance and violence.

See: Faisal Al-Samir, Thawrat al-Zanj (Baghdad, Maktabat al-Manār, 1971); Johan Franzén, Red Star Over Iraq: Iraqi Communism Before Saddam (Hurst, 2011), 179.

Ryan Manya, “’The Hidden story’: Life as a young Marsh Arab,” Substack, ➝.

UNEP, Early Warning and Assessment Technical Report, The Mesopotamian Marshlands: Demise of an Ecosystem (2001), ➝.

Kassem Hawal, Al-Ahwar (The Marshes): Film Scenario and Experience (Tunisia: Nathar Publishers, 2019).

As a rejection to the dictatorial Ba’ath party rule, Hawal left Iraq as they came to power and joined the Palestinian Resistance Movement in Lebanon. He was later perused to return temporarily to Iraq to film the marshes. Hawal sought political asylum in the Hague where he currently lives.

UNEP, Early Warning and Assessment Technical Report.

C. Jones, M. Sultan, E. Yan, A. Milewski, M. Hussein, A. Al-Dousari, S. Al-Kaisy, R. Becker, “Hydrologic impacts of engineering projects on the Tigris–Euphrates system and its marshlands,” Journal of Hydrology 353, no. 1–2 (2008): 59–75.

Ariel Ahram, Development, Counterinsurgency, and the Destruction of the Iraqi Marshes (International Journal of Middle East Studies, 2015).

James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (Yale University Press, 2009), 8.

In a panel discussion held at New York University on October 26, 2004, cosponsored by Carnegie Council, Environment Conservation Education Program, New York University, the Al-Khoei Foundation (UK), and the Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies, New York University, Joanne Bauer quoted Max van der Stoel, Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Iraq, who briefed the UN General Assembly in response to the internal inter-agency memorandum ordering the destruction of the marshes.

Ryan Manya, “The Marsh Arabs and their Conflict with the Modern State,” Middle East Voice (November 9, 20222), ➝.

NASA Earth Observatory, “World of Change: Mesopotamia Marshes,” ➝.

Roz Price, Environmental risks in Iraq (Institute of Development Studies, 2018), ➝.

“The National Atlas of Marshes and Wetlands in Iraq,” Nature Iraq, ➝.

These studies have been fundamental for further comprehensive research endeavors in the area spanning archeology, anthropology, biology, and environmental sciences

Jassem al-Asadi, phone conversation with author, January 23, 2023.

Abu Haidar, conversation with author, December, 2022.

“Jassim Al-Asadi: ‘kidnapped’ environmental activist campaigning to preserve the marshes in Iraq,” BBC Arabic (February 5, 2023), ➝.

Hydroreflexivity is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and “Fertile Futures,” the Portuguese Pavilion at the 18th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia curated by Andreia Garcia with Ana Neiva and Diogo Aguiar.