Georg Vrachliotis What are the biggest issues facing housing today?

Nathalie de Vries We have to create livable cities while living together with ever more people, and at the same time keep public services accessible and housing prices affordable.

GV Architectural experimentation has always been a central component of housing. Today, experimenting seems increasingly difficult in the face of global building standards and norms. How do you deal with this in your practice?

NdV It is very important for architects to use any and every space for experimentation that we can. In our work, we split research between studies of the near future, which allow us to dream about possible futures, and day-to-day projects, where we always try to experiment with at least one aspect of the design. We’ve found that one of the most important aspects of the design of housing today is its transformability, that its functions can change and evolve over time. What kind of structures and designs do we need for that? We can learn from architects such as Frei Otto here, who put research into structure at the core of his designs, which allows a lot of freedom for other aspects of buildings.

MVRDV, Markthal, 2014. The apartments follow strict Dutch laws regarding natural day-light: all rooms that require natural light are situated on the outside. Kitchens, dining rooms and storage are placed along the internal envelope, establishing a connection to the market.

GV Which architects and projects have influenced you personally on questions of housing?

NdV My personal starting points were J.J.P. Oud, who combined ideas about standardization with affordability and urban design. I was also greatly inspired by Gerrit Rietveld and Truus Schröder, for their radically different approach to floorplans and the relationship between interior and exterior.

GV Housing is often treated as an anthropological constant. Nevertheless, change happens. What are some of the biggest recent changes that you have seen?

NdV A house can be used in so many more ways than just for a typical nuclear family. As a consequence, we need more undetermined spaces, more freedom to subdivide and combine rooms, more shared spaces with neighbors and co-inhabitants of buildings; more mingling of different types of people and less traditional thinking about living and family structures. On an individual level, the idea of a comfortable dwelling might have timeless qualities, but there is still much to learn about what it means to live comfortably today. Our traditional homes are holding us back in our possibilities to dwell.

GV From the very beginning, housing has been a central and consistent focus at MVRDV. How has your approach changed over the years?

NdV When we started, we focused on two things. One was the possibility to densify with higher quality, and the other was the possibility to offer more variety for finding an ideal home. For example, in our Silodam project in Amsterdam, we designed numerous differently-styled yet same-sized apartments, and clustered them in mini-neighborhoods. Over time, we have worked on advancing the possibility for inhabitants to personalize their homes. Our Niewe Leyden project in Leiden allowed for hyper-personalized townhouses in a strict masterplan of blocks. We have experimented with this further via software-aided design programs like Village Maker, where people can co-create towers made of individual and freeform homes. And our Almere Oosterwold masterplan allows people not only to build their own dream home but also to create their own surroundings.

GV Programming seems to play a major role in how you position housing in society. Your projects increasingly create a radical mix of housing and other functions.

NdV Mixing housing with other functions has turned from a theoretical ideal, as we originally proposed it in Farmax (1998), to a fundamental part of all our designs as executed today. For example, in the Market Hall, in Rotterdam, two slabs bend to meet at the top to form a new covered space that becomes the market hall. Rather than optimizing space by just piling functions one on top of another, we always try to form a new hybrid solution, creating extra possibilities, often in the (semi-)public realm. This is important for creating lively cities. Overall, we want to apply strategies of densification while at the same time creating more space for housing in every price range.

GV What is the housing situation like in the Netherlands today? What do you feel are some of the most important aspects shaping its future?

NdV Three of the biggest issues we are facing today are how to make housing more sustainable, how to build more affordable houses and solve the enormous housing shortage without destroying our last open areas, and, lastly, how to deal with demographic changes like an aging population and lack of diversity in certain areas. These problems are not exclusive to the Netherlands alone. It remains important that housing is not just left to the market but also taken up as a serious public, architectural, and urbanistic task. The role of Dutch housing corporations, however, which used to push avant-garde design and address these types of issues, has unfortunately been lost.

GV In the history of architecture, the question of housing is often seen as an interface with other disciplines: technology, for example, when it is about infrastructure or climate; sociology, when it is about the connection to the city or to public space; economics, when it is about social housing or the privatization of city centers; or even psychology, when it is about the perception of interiors. How do you find this situation today? Which other disciplines play a role in contemporary housing?

NdV Nowadays, building technology is very important. We are at the brink of a huge paradigm shift in how we build. More sustainable and transformable building systems are necessary, as well as new standards for materials, which should be re-usable, but without becoming too expensive. Secondly, artificial intelligence plays an important role: from digital printing of materials to customization of building parts by users, parametric design, and the internet of things.

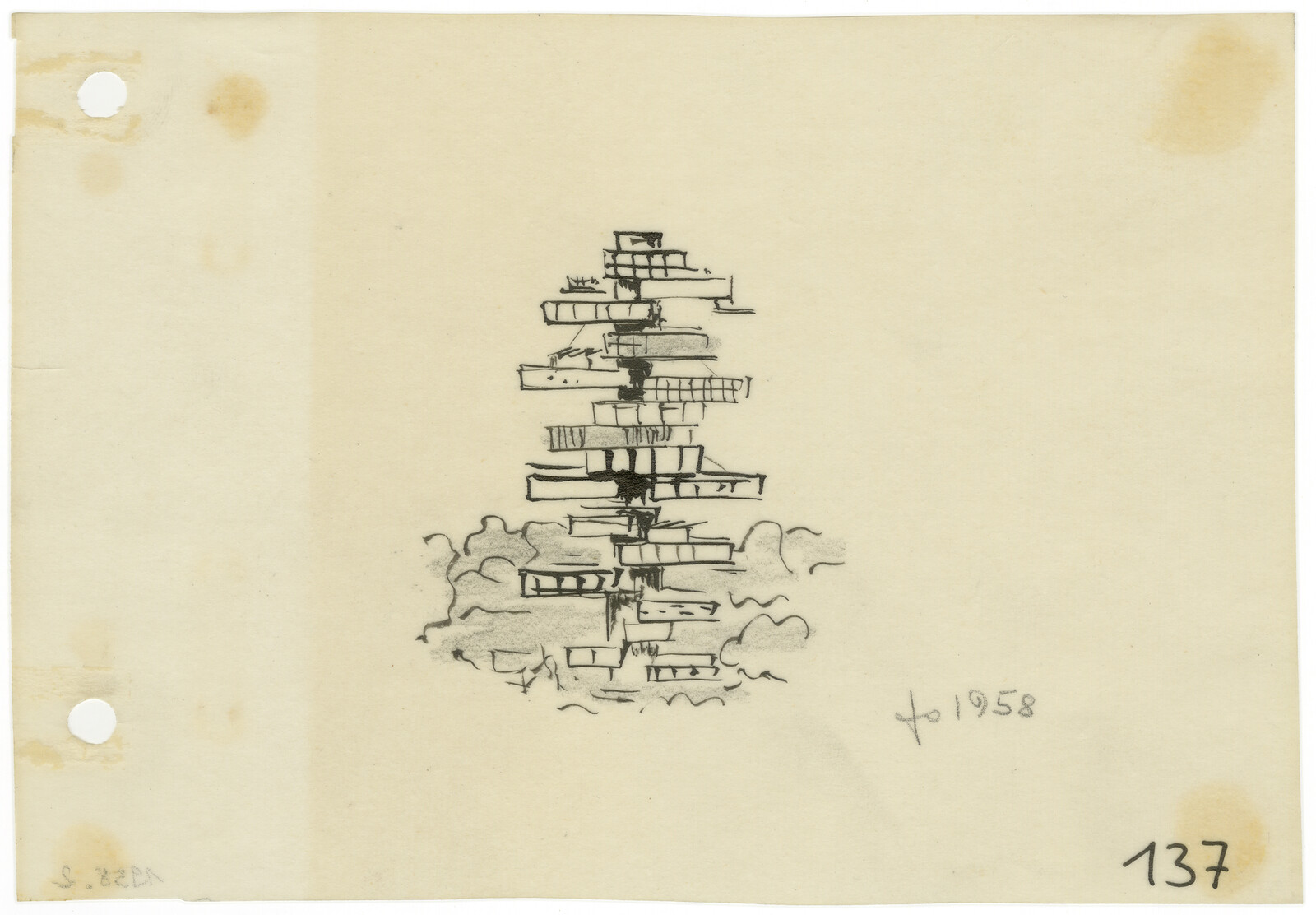

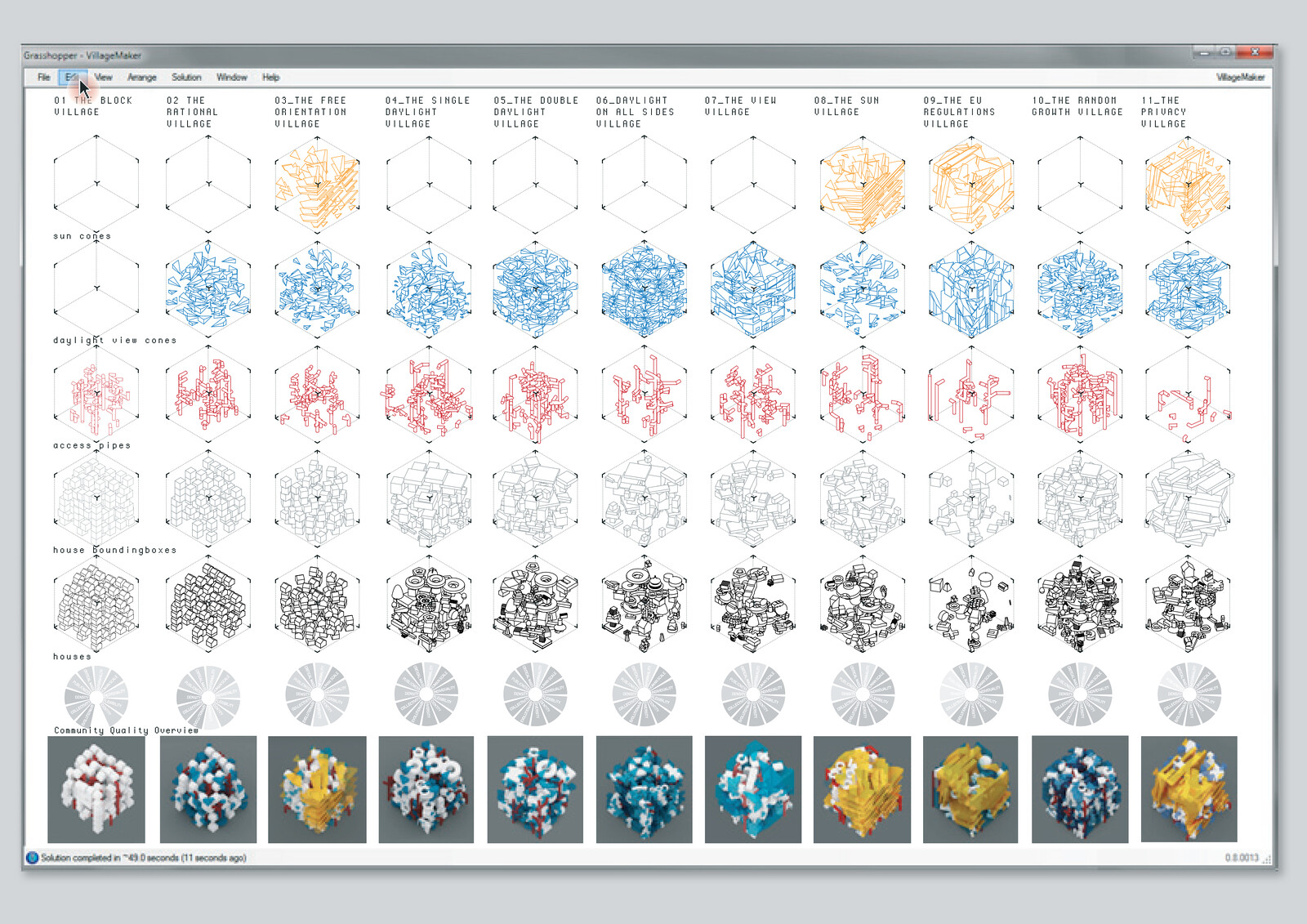

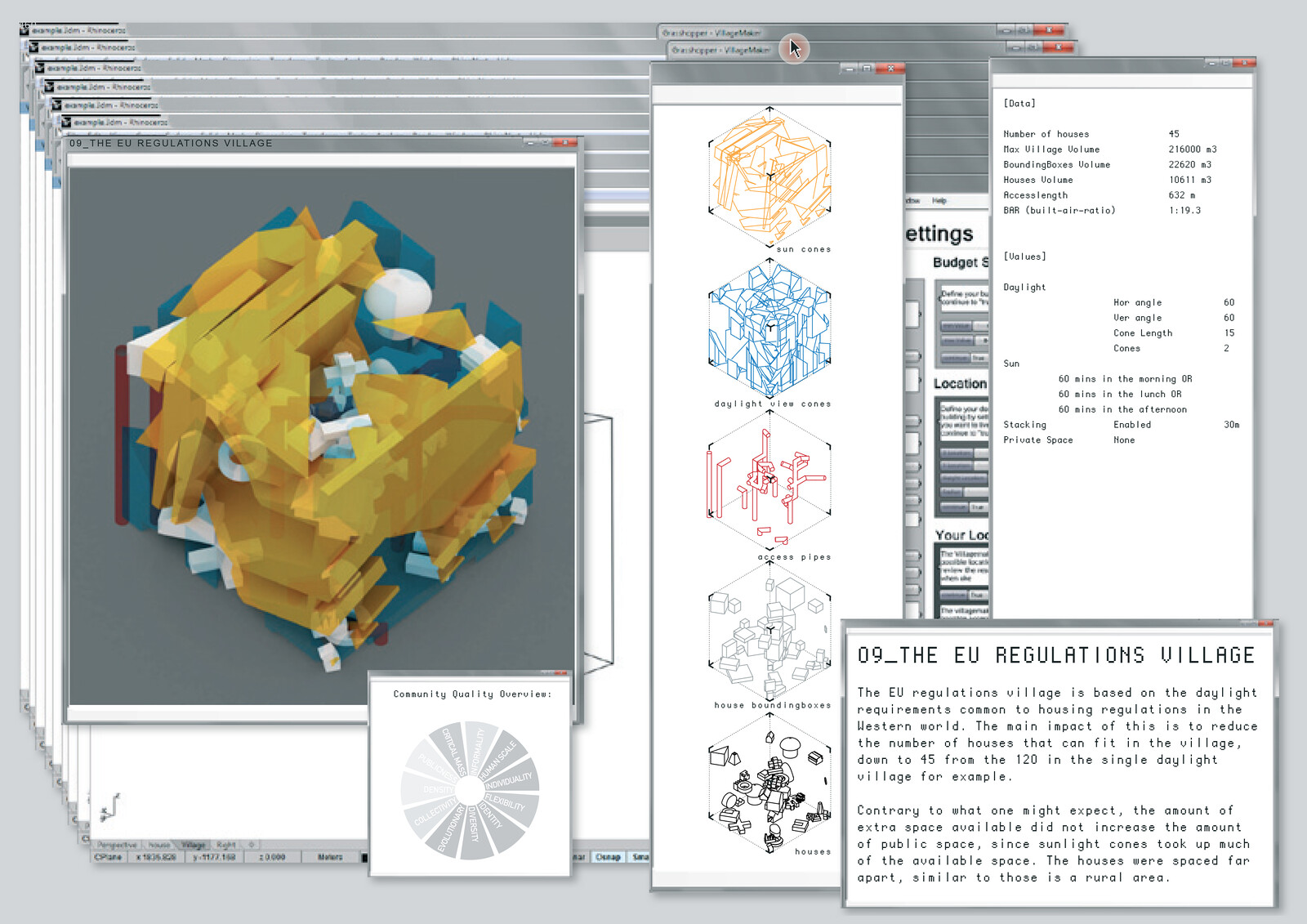

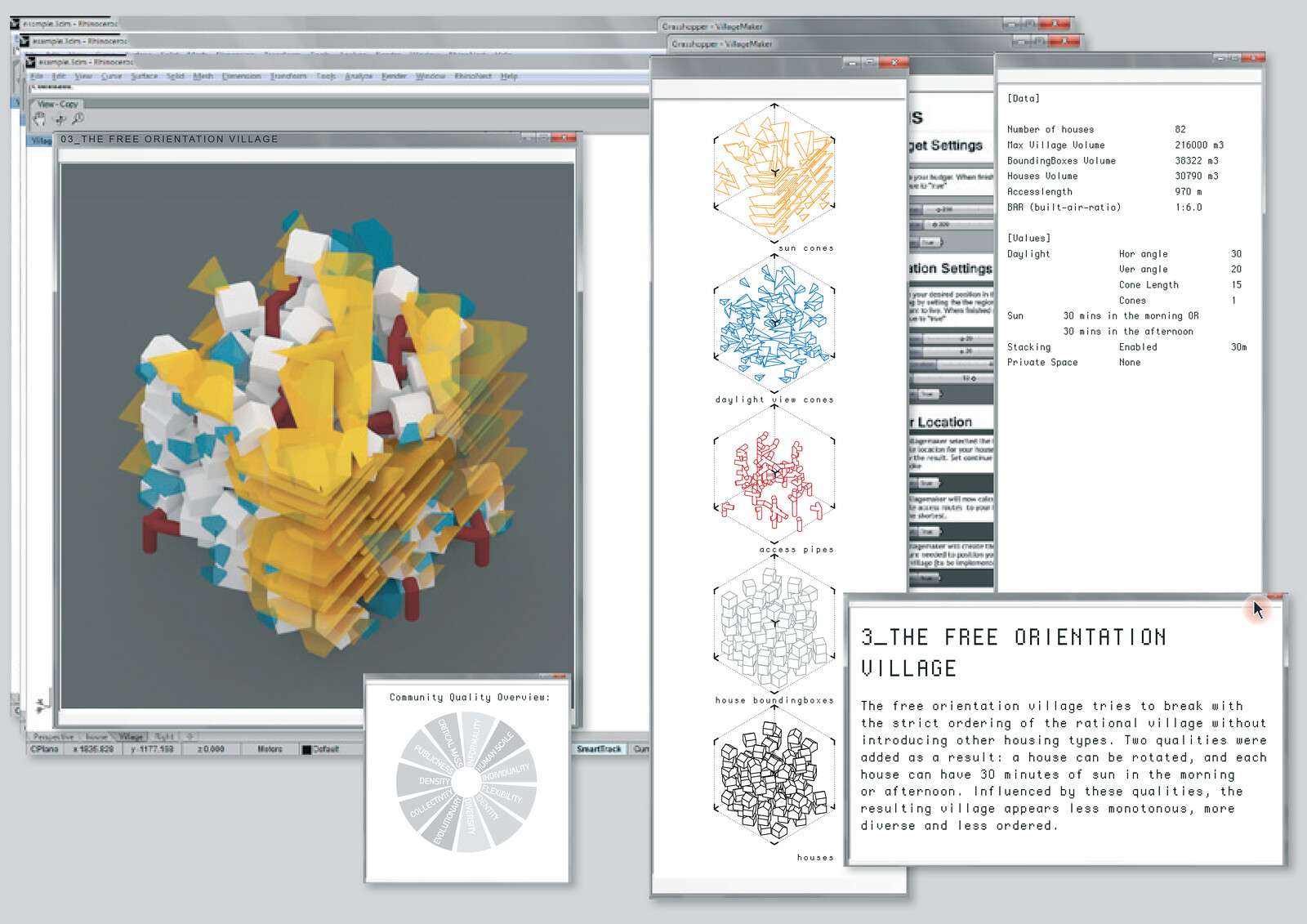

MVRDV’s VillageMaker© is an open-source software program that allows future inhabitants to collectively develop a vertical village in an evolutionary way. The program is a tool for supervision and a platform for negotiation, without the need for a masterplan or the involvement of urban planners. After setting user criteria for sunlight, view, privacy and preferred area, the program shows where the house could be built, and specifies the associated costs.

MVRDV’s VillageMaker: The EU Regulations Village.

MVRDV’s VillageMaker: The Free Orientation Village.

MVRDV’s VillageMaker© is an open-source software program that allows future inhabitants to collectively develop a vertical village in an evolutionary way. The program is a tool for supervision and a platform for negotiation, without the need for a masterplan or the involvement of urban planners. After setting user criteria for sunlight, view, privacy and preferred area, the program shows where the house could be built, and specifies the associated costs.

GV The digital transformation of society has changed not only cities, but also ideas around housing. To what extent has digitalization created new forms of housing, or updated old ones?

NdV Office work can now be done everywhere, so there is a blurring of spatial functions, as well as a fluidity in our lives. The worker’s home has become a relevant question again. But in general, digitalization means more for how we use our cities (we still need meeting places) and for interiors than for buildings per se. I hope this will lead to a more open floorplan becoming the norm, with fewer fixed uses and furniture configurations in mind.

GV MVRDV was one of the first offices to deal intensively with datafication. How has the discussion about data changed in architecture in general, but with regard to the housing question in particular?

NdV Data-driven design is really important, as it helps us optimize our designs. We also try to deal aesthetically with the datascapes that arise from this optimization. A second important application is the possibility for participation, offering users the possibility to interact with and change our designs via software and apps. This is still in its early stages, but it could potentially become the dominant way of designing homes and neighborhoods. For architects, it is increasingly important to engage in the creation of these design tools and softwares. Smart building systems can help both architects and users learn more about the performance of buildings. Key to this, however, is for designers to maintain access to the information produced by smart buildings. Smart building systems also call for a completely new type of building code and new regulations to be developed.

Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture.