Staircases can be perspicaciously complex. The staircase is one place where architects visually and physically connect people within buildings, and where they can directly reveal critical thinking in relation to a building’s form and its function. The staircase is a significant form of public space, not to be underestimated in creating or curtailing human activity and engagement. No multi-story building can avoid them. Staircases are unequivocally shared. Within them, individuals interact not only with the physicality of the building but with each other, directly: acknowledge one another, look at each other, talk to one another as they causally pass by one another. They are spaces where people move together, even if awkwardly, going up and down. Unlike a façade, which typically has a singular function to protect the interior from the exterior, the stair enables a multitude of uses and experiences.

Staircases form spaces for shelter, interaction, performance, exercise, conversation, play, protest, etc. More than a straightforward connection between two adjoining spaces, staircases—particularly in housing—represent the importance of equitable and just access as a passage from the street to interior common spaces to living spaces. How a staircase is treated reflects societal concerns, both inwards towards its residents and outwards towards society as a whole. The staircase is a place of motion and encounter, and therefore of politics. It is fundamentally different, in this sense, from any other element of a building. An internal staircase has different politics than an external staircase; an enclosed stair is different than an open stair. Staircases are limiting to those who cannot physically use them, and require the proximate location of an elevator. While it’s the norm in housing projects to wall off either use from the other, thus segregating their respective user groups from one another—all due to “fire protection”—this need not be the case. With staircases, politics is a question of design.

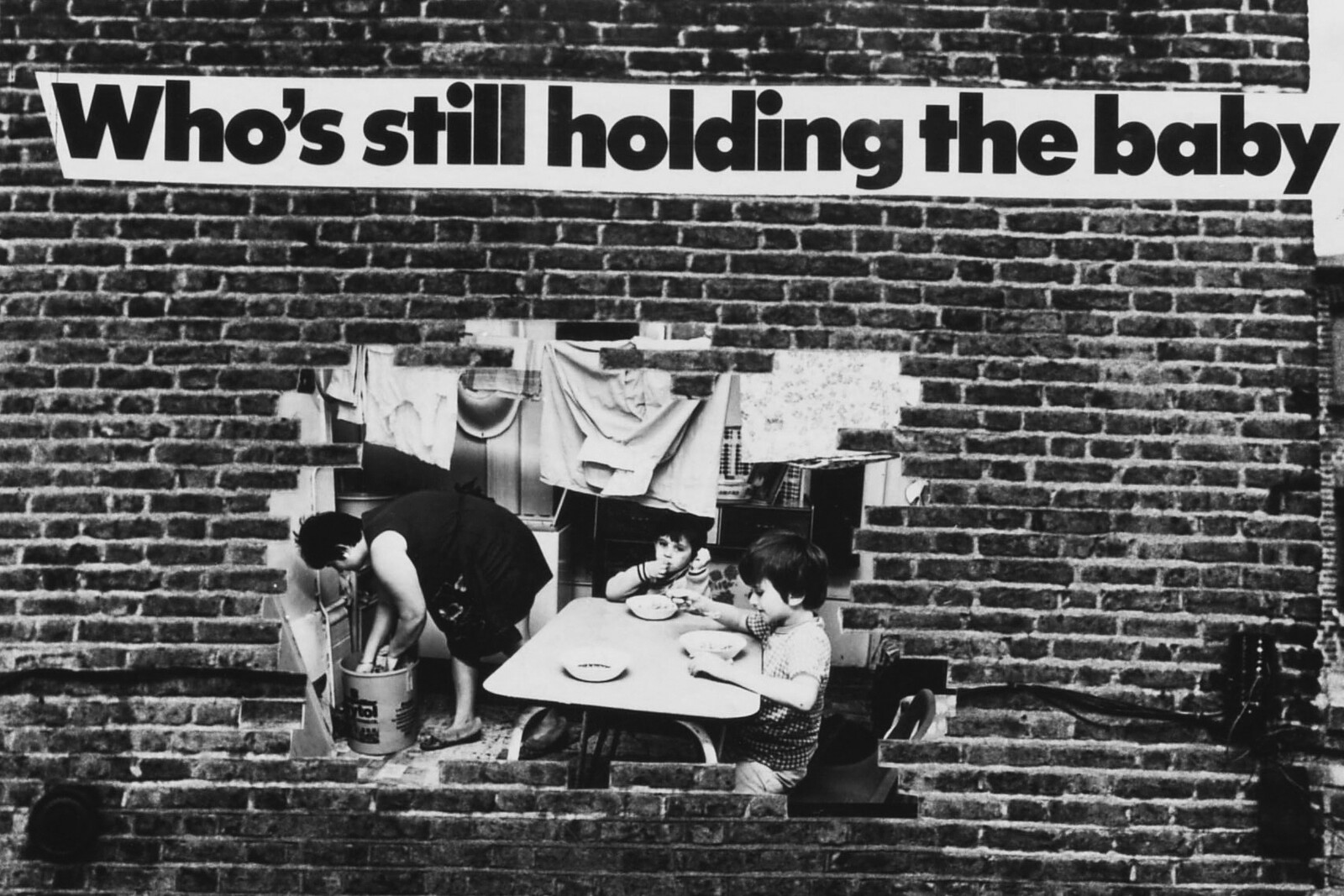

Staircases in housing suffer harsh critique, particularly in social housing where particular burdens are placed upon them. They are frequently discussed and devalued for their failures. Staircases might be poorly maintained; they may be too dark, too small, the least designed, unheated, avoided, underused, unoccupied, and potentially dangerous. Inherent to this critique is a belief in the staircase’s potential to create a space for positive communal exchange. Concerns around housing tend to focus on living spaces—the apartment—yet circulation space is the first space anyone must pass through before arriving to an apartment. Circulation space should not be a secondary concern, but a primary one, and staircases should be treated as if they are as important as elevators and ramps when designing the inclusivity of space.1

Staircases are discrete elements within any building. Particularly in housing, the various forms and locations they take significantly impact the design and ultimately the use of the building as a whole. The economic model of affordable housing in the United States, for instance, strives towards a minimum of 85% rentable or purchasable floor area, thus constraining circulation spaces to a bare minimum. However, numerous typological alternatives to the code-dictated minimum of two closed-off egress stairs exist in the history of architecture. Alternatively conceived, staircases can make a positive difference in the perception and actuality of a collective. At the same time, they can impede its formation.

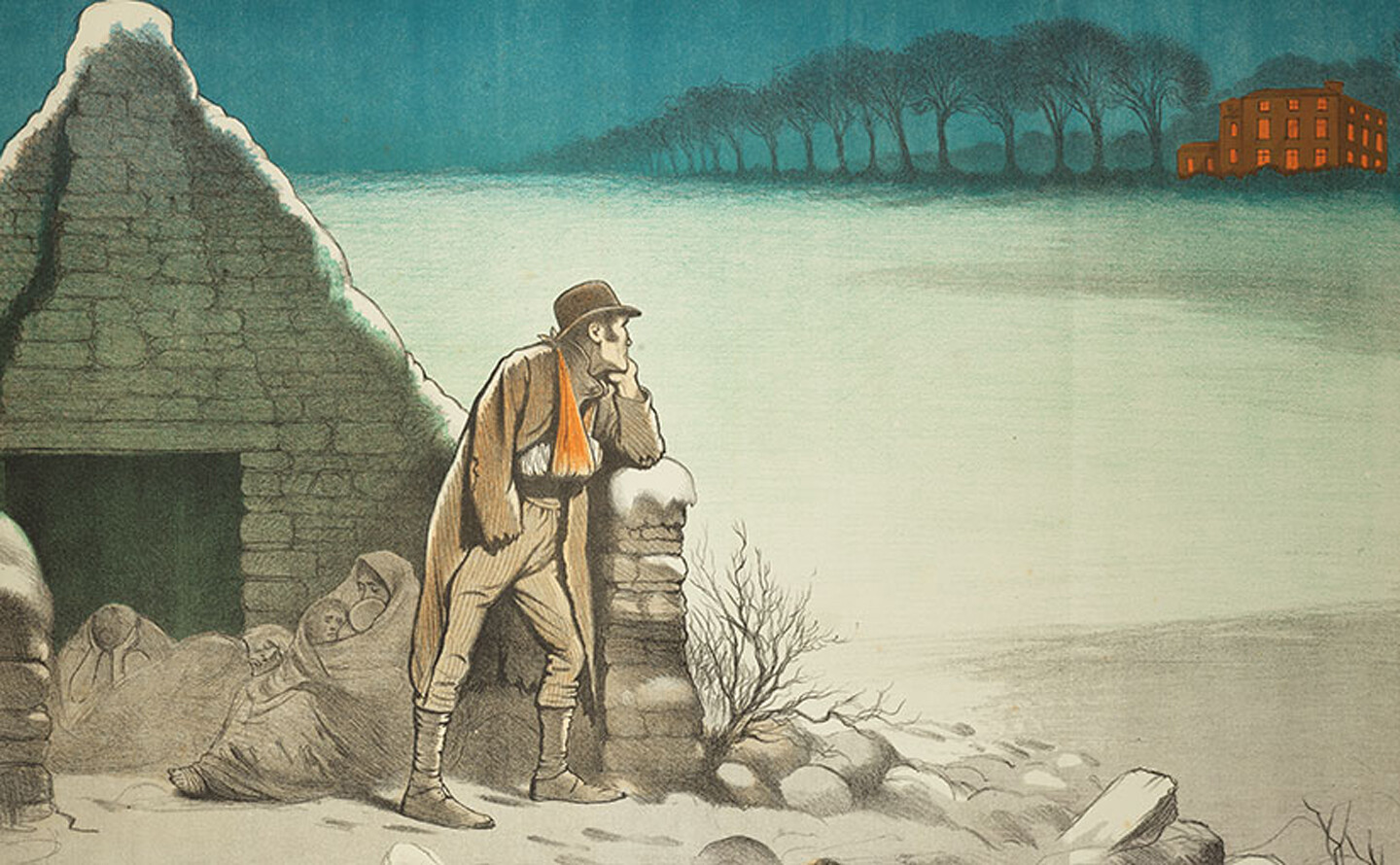

Housing should be a universal right. In order for that to become a reality, housing needs be interpreted in the broadest of terms, meaning not only as a group of interior, enclosed, protected dwelling spaces, but also the public spaces that connect them and make them a whole. It isn’t enough to provide only a minimum number of units or “products.” If people have the right to housing, it should be possible to observe and experience the enactment of those rights across all scales of a built form. The right to housing should include well-designed, well-lit, well-formed, accessible circulation spaces. Staircases offer an opportunity to reimagine how society can live.

Staircases structure peoples’ interaction with one another, both those residing there and those visiting. There are many states of staircases. A stocktaking of staircases in residential buildings offers a look into architecture’s relationship to circulatory systems and other building systems. With the invention of mechanically supported circulation such as escalators or elevators, the staircase has not been “superseded,” but is still “rendered a nuisance and built to the minimum that code permits.”2 Staircases reveal the nature of buildings to be beyond a formal disciplinary problem. The staircase is the place for a careful making or a difficult unmaking of a community or collective.3

What follows is a series of notes from an ongoing design research project, one that began through investigations into housing’s complimentary spaces. What happens when it is no longer possible to climb stairs, or what is the experience of a building if that use is lost? What experience is needed in its place? What happens to the community of a building in the absence of shared circulation, or of a lack of motion? As architects execute services, there are often limitations on what can be designed or built. Understanding not only why but also how certain stairs are designed and constructed is useful for rethinking contemporary and future practice. Further research on stairs as important cultural artefacts is needed.

Santos Prescott and Associates, Iona Street Apartments, Cape Town, South Africa, 1971. Source: Santos Prescott and Associates.

Santos Prescott and Associates, Iona Street Apartments, Cape Town, South Africa, 1971

This thirteen-unit, twenty-foot-wide residential building built for students and an artist by architect Adele Santos was carefully designed around a sloping bridge for a street-level entrance and open-air exterior corridors to transverse the length of its narrow site. Building upon principles of both European architectural modernism and local vernacular designs, the all-white PVA-covered concrete-and-glass building also has a set of stairs that meets the city sidewalk, and an inclined ramp for vehicular access and parking. Internal staircases protrude out into public corridors, demarcating each unit’s form. They are stacked to produce a rhythm in the main façade along the open-air shaded corridors. In the interior of the units, the staircases separate utilities from living space. The staircases themselves serve as an entry, the transition space between each unit and the corridor, physically and acoustically separating the private from the public.4 As an abstract form, the undulating modules of the stacked stairs give shape to a dynamic public space where residents can commingle and convert what would typically be enclosed and private space into an opening towards neighbors.

Frei Otto and the future inhabitants of Oköhaus, ca. 1982. Source: The Offbeats/L’architecture engagée - Manifeste zur Veränderung der Gesellschaft.

Frei Otto, Oköhaus, Berlin, Germany, 1982

Prior to its construction, Frei Otto worked intensively with the future residents of his Ökohaus project to design their individual units or houses. A photograph of one of these collective workshops captures a group of people gathered around an architectural model with a simple, generic structural frame, infilled with diverse designs. Another photograph shows a similar scene, but adjacent to the building models are two model staircases. Apparently modeled out of paper, they stand in contrast to the bricolage approach taken to the rest of the model, and ultimately the building as a whole once built. While the models suggest that the staircases are not integral to the overall design of the building, and could seemingly fit in where needed, it is the one part of the building where residents would interact and confront one another. The staircase is not only representative of the participatory design process as a whole, but also it is the only inhabitable space of Ökohaus not designed by the tenants, but by Otto himself. They are ultimately the very thing that enables the housing project to create a physical community.

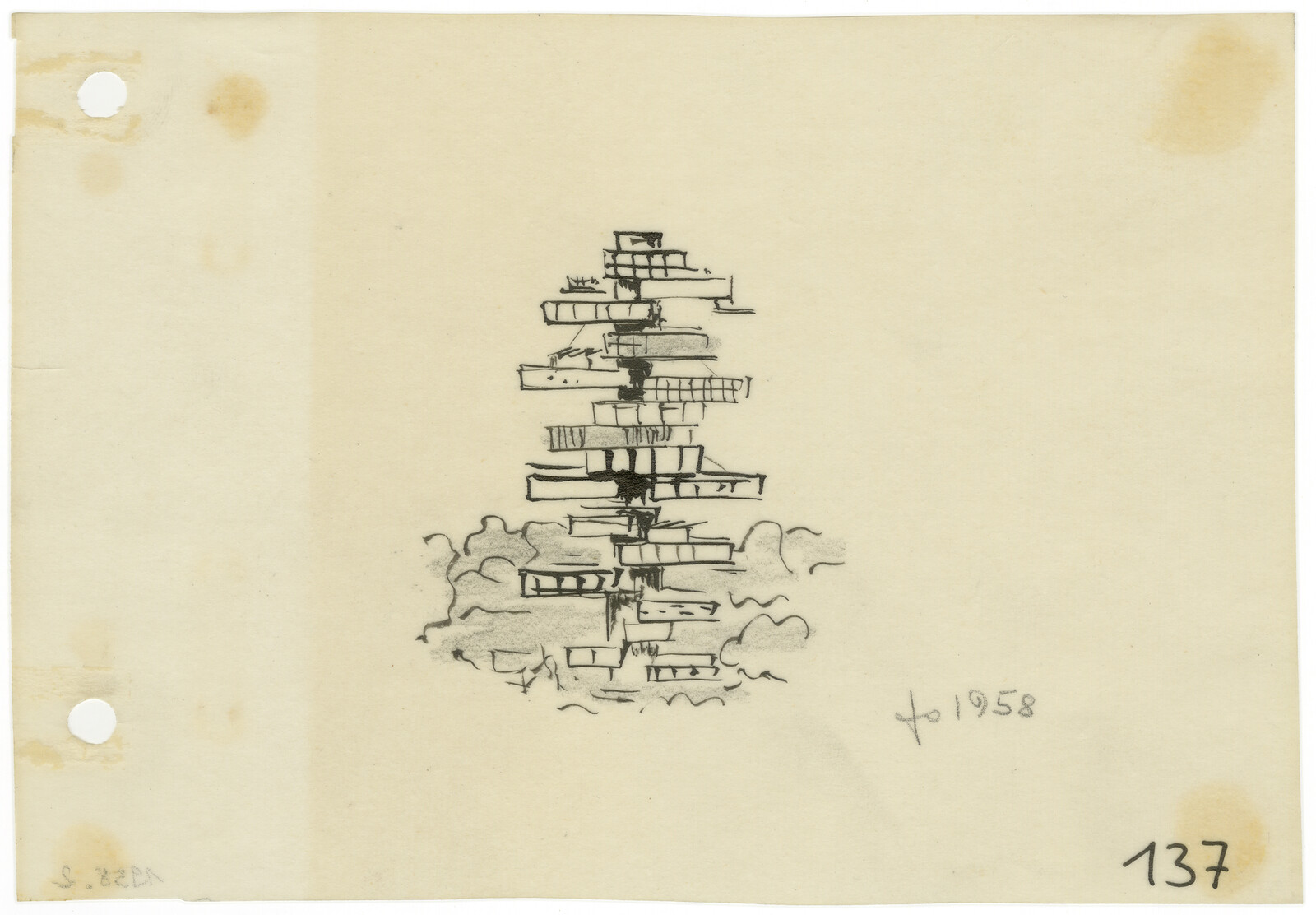

Incomplete plan drawing of Guild House in Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966).

Robert Venturi, Guild House, Philadelphia, USA, 1963

In Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, Robert Venturi’s design for the “elderly housing” Guild House project is presented only through an incomplete plan drawing.5 In the accompanying written description, however, nearly every part of the building is described, but not the stairs, or any other form of vertical circulation.6 The symmetrical plan has the left side drawn in more detail than the right, which is reductive to the point of omitting the lines of the staircase; only the outline of the stairwell walls remain. This suggests that Venturi understood these stairs to be singular in their function. A staircase is a staircase is a staircase. People go up and down. Interestingly, however, he notes later in the book that one remarkable element of a Victorian house is that its staircase is more flexible and open to alternate uses than a public staircase, despite the openness and comings and goings of many people.7 A private space with a stair can accumulate things and activities; it can entertain clutter and unplanned use.

Adjaye Associates, Sugar Hill, New York City, USA, 2015

Affordable housing projects often suffer from a lack of cultural or educational public experiences in their programs; too often their ground floors are filled with commercial spaces that are likely to become vacant, rendering the building incomplete and isolated. At Adjaye Associates’ Sugar Hill, ground floors are filled with educational and cultural programs that extend out and invite the local community and neighborhood in. This affordable, below-market-rate residential building includes housing for formerly homeless people, an early childhood education center, a Children’s Museum of Art and Storytelling, offices for the developer Broadway Housing Communities (BHC), and an urban garden welcome space.8 The building is situated on a steep sloping site in the historically-significant African-American Sugar Hill neighborhood in Harlem, at the crossroads with a Latino community. It is designed using graphite-tinted precast panels with an embossed rose pattern that recalls the neighborhood’s tradition of ornamental detailing, while the building’s sawtooth and stepped form references the brownstones nearby. Residents are required to sign in when entering the building—no guests are allowed—and amenity spaces are limited, other spaces are given to the residents elsewhere. The efficiency of the plan of the 124 residential units above—a double-loaded corridor and typical fire stairs—enables public spaces below to be enlarged. The museum’s street-level entrance lobby and bookshop contain seating and connect to a wide wooden stair. Its interior landing, which feels like a balcony and brings light into the working spaces below, serves as a transitory gallery before terminating in a large open space with built-in auditorium-like seating for events and rest. From this stair it is possible to be a part of the museum and look out over the city at the same time.

Mario Pani, CUPA (Centro Urbanos Presidente Miguel Alemán), Mexico City, Mexico, 1949. Source: vladimix/Wikimedia Commons.

Mario Pani, CUPA (Centro Urbanos Presidente Miguel Alemán), Mexico City, Mexico, 1949

All 800 units in Mario Pani’s CUPA complex are connected through open-air corridors and switchback staircases. It is possible to traverse the zig-zag building from end to end without ever touching the ground. Small sets of stairs between buildings navigate slight shifts in the building’s floor elevation, allowing the buildings to move in response to seismic activity. The staircases, located at the end of each corridor, are wide enough for people to comfortably pass one another. Each corridor is enclosed with a guardrail that contains planter boxes for each tenant and, at the intersection of staircase and corridors, a space for potted plants creates a lush environment set against the brick, concrete, and stone walls. The staircases are not only a means of moving up or down, but, in contrast to the linearity of the corridors, they offer continuously changing views of both the immediate surroundings, the city, and the mountains in the distance. The staircases are offset from the plan, and their landings allow for a measurable pause. The majority of the residences have internal staircases, furthering this movement as residents ascend to a living room with horizontal windows looking up and outward, or descend into kitchens and work spaces that are more inwards and closed. While the building is also serviced by elevators, the scale of the building requires continual movement by walking.

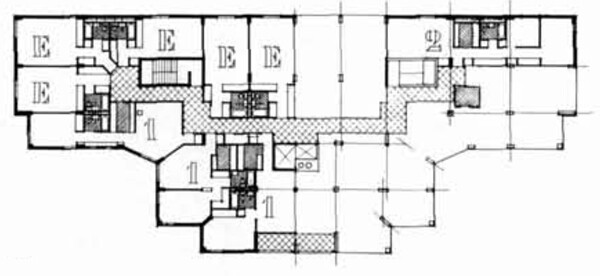

O. M. Ungers, Block 1 IBA, Berlin, Germany, 1987. Source: Raumgestaltung RWTH

O. M. Ungers, Block 1 IBA, Berlin, Germany, 1987

Outwardly uniform, symmetrical, cubical, and repetitive, O. M. Unger’s Block 1 IBA is anything but predictable or familiar in the interior. The organization of the plan is not, as might be typical of a form like this or a building of this size, around a double-loaded corridor. Rather, it favors floor-through unit plans with natural light on both sides. The architect’s focus on the repetition of a variety of residential units creates interrelationships that are not immediately visible but can be understood with careful study.9 The six-story, forty-eight-unit residential building consists of more than fifteen different unit types, all organized around a central, shared, open-air courtyard with four staircases, one at each corner, like the traditional Berlin block. Each staircase, in turn, serves a select set of apartments, thus breaking down the building into smaller clusters. Smaller groups of residents share an entry, an elevator, and a staircase to their individual apartments. Tenants might not know everyone passing through the courtyard, but they would at least likely know their neighbors all the more.

Alvaro Siza, Punt und Komma, The Hague, Netherlands, 1986–1988. Source: Archipicture.

Alvaro Siza, Punt und Komma, The Hague, Netherlands, 1986–1988

In order to achieve other spatial and material economies, social housing often sends it residents through lengthy sequences of interior spaces to access units, at the expense of security and community. Alvaro Siza has said about stairs: “When you enter a building there’s a moment when you come to a stair and you have to stop. Then you must make the effort to position your feet, and then hold onto the handrail, otherwise you’ll fall. For this reason, it’s a crucial episode in a building and this is always extraordinary.”10 In this four-story collective housing project in the Hague, Siza reimagines this philosophy of stairs in transitioning from a series of public collective spaces to private living spaces, all the while responding to the domestic and urban needs of the neighborhood’s diverse residents of Islamic, Dutch, and Southern European heritage. Ensuring security by increasing visibility of residents coming and going from their homes, each unit is accessed either by doors directly facing onto the street or by overly-wide outdoor staircases that puncture the façade and move into the depth of the plan. Leading up to elevated landings with multiple entrances, each one forms a kind of sheltered townhouse stoop, typical of Dutch housing.

Alvaro Siza, SAAL Bouça Social Housing, Porto, Portugal, 1972–2007

Rows of rectilinear stucco housing units stand adjacent to one another across a series of open courtyards in Alvaro Siza’s SAAL Bouça Social Housing project in Porto. One courtyard offers direct ground-floor access to lower-level duplex units, while the next is lined with more than twenty open-air staircases, one for each upper-level duplex unit. Connecting directly with the city’s sidewalk network, neighbors come and go for all to see in these staircase-lined courtyards, which are frequently used by residents for collective celebrations, festivals, and holidays. In contrast to the wide and accommodating external staircases or open-air balcony-type lateral hallways typical to social housing, these unusually narrow and steep staircases—with the thinnest of handrails—dignify the threshold experience of leaving the city and entering one’s own home.

Farshid Moussavi Architecture, Îlot 19 La Defense, Nanterre, France, 2017. Source: Farshid Moussavi Architecture.

Farshid Moussavi Architecture, Îlot 19 La Defense, Nanterre, France, 2017

In Farshid Moussavi’s Îlot 19 project in Paris, a multitude of discrete staircases with elevators repeat across the ground floor plan to provide private entrances for pairs of individual units, mostly for students, thereby eliminating the need for common corridors and minimizing collective interaction between all residents.11 Smaller groups are favored to larger ones. As a result, horizontal circulation can be turned inside out and recast at the building’s perimeter in the form of deep covered balconies, giving residents expansive views of the city from the upper part of the building. With a range of apartment types, including seventy-two affordable units, nine social housing units, and a singular level of maisonette penthouses, the building is purposefully designed to segregate tenants with different lifestyles, allowing them to live collectively within one building but maintain their autonomy. In a complete reversal of housing projects that often make units specific and public spaces generic, however, durable materials of anodized aluminum, glass, concrete, and hardwood flooring are used in spaces of circulation, while the dwelling units are left bare for residents to make them their own.

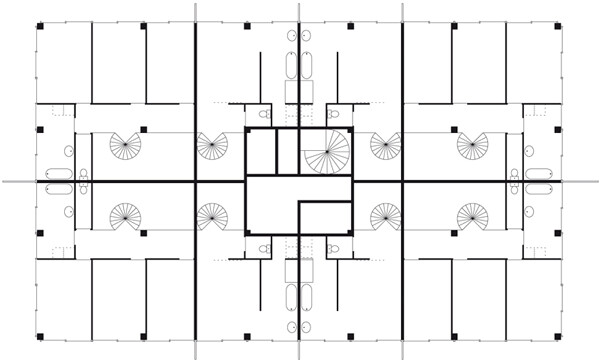

Lacaton & Vassal, Housing Hérouville-Saint Clair, second-level duplex plan, Caen, France, 2000. Source: Lacaton & Vassal.

Lacaton & Vassal, Housing Hérouville-Saint Clair, Caen, France, 2000

Lacaton & Vassal designed a series of units with individual interior spiral stairs, as well as a central fire stair at twice the radius of their proposal for housing at Hérouville-Saint Clair. Across a field of rectangular units, the regular circular markings of the spiral stairs abstract the plan and turn it into a repeating geometric pattern that complements the circular profiles of existing cylindrical water tanks adjacent to the site. The floorplans of the individual units have a noteworthy efficiency, provided by the tight radius of the spiral stairs. In duplexes, the second-floor landing is compressed to such an extent that the stairs directly lead out onto to the bedrooms beyond. Repetition and variation afford a wide variety of lifestyle and domestic arrangements, even within this constrained “kit of parts.” The spatial economy of the core affords unusually broad exterior terraces around the full perimeter of the residential floors.12 Here ground floors are converted into open spaces or parking with spiral stairs

Kazuyo Seijima, Gifu Kitagata, Gifu, Japan, 1996.

Kazuyo Seijima, Gifu Kitagata, Gifu, Japan, 1996

Kazuyo Seijima’s design for the Gifu Kitagata residential building was part of a large-scale public housing reconstruction project coordinated by Arata Isozaki & Associates. Staircases connect the open-air ground-floor parking spaces to the 107 maisonettes and other two-story units hovering above on pilotis. Metal staircases continuously ascend along the façade and provide access to exterior corridors that connect and provide access to each of the individual units. Interior stairs are located at the perimeter of the window wall and lead to the terrace in each unit. The glass and visibility activate the building, forming a dynamic public identity. “The silhouettes of people moving inside will be visible on the south façades just like on a cinema screen.”13

LOT-EK, Drivelines Studios, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2019

Working in the Maboneng neighborhood of Johannesburg, LOT-EK used abandoned shipping containers to build 100 apartments. Stacked as two independent bar buildings forming a “V” shape, external staircases look out over an internal courtyard and associated public spaces. The faded brands and original colors of the seventy containers used set the backdrop for the oversized, perforated metal staircases and corridors. The staircases themselves have enlarged landings that serve as viewing platforms towards the brutalist architecture of the city’s central business district. While they have the potential to host crowds of people commingling, the shared corridor balconies can be apportioned to each unit when not in more collective use. The stairs enable an expanded life for the apartment building that is at once enclosed and secure within the courtyard, while also allowing for an ebb and flow of common spaces and occasionally a cascade of people.14

Thank you to Thomas de Monchaux for reading and making suggestions on the working text.

John A. Templer, The Staircase: History and Theories (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1992).

Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain: Making and Unmaking the World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987). See also the American with Disabilites Act, ➝.

This project was built for a family member, who lived in the building and rented the remaining spaces to students. Thanks to Adele Santos for the interview, and to Mario Gooden for recommending Ilze Wolff’s important blog, ➝.

Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (New York: MoMA, 1966), 116.

There is no mention even of the elevator, which would be needed to ascend to the highest floor and the main room where residents were to watch television overlooking a framed view of the Philadelphia skyline.

Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, 130.

Susanne Schindler, “Architecture vs. Housing: The Case of Sugar Hill,” Urban Omnibus, September 3, 2014, ➝.

O.M. Ungers: Works in Progress 1976-1980, eds. Kenneth Frampton and Silvia Kolbowski (New York: Rizzoli, 1981).

Kenneth Frampton, Álvaro Siza Vieira: A Pool in the Sea (IITAC Press, 2018), 40.

Farshid Moussavi, “Îlot 19 La Défense,” ➝.

Lacaton & Vassal, “23 dwellings, Trignac,” ➝.

Joseph Lluis Mateo, Global Housing Projects: 25 Buildings since 1980 (Barcelona and New York: ETH/Actar, 2008).

Karen Eicker, “Drivelines by LOT-EK,” Architectural Record, October 1, 2018, ➝.

Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture.