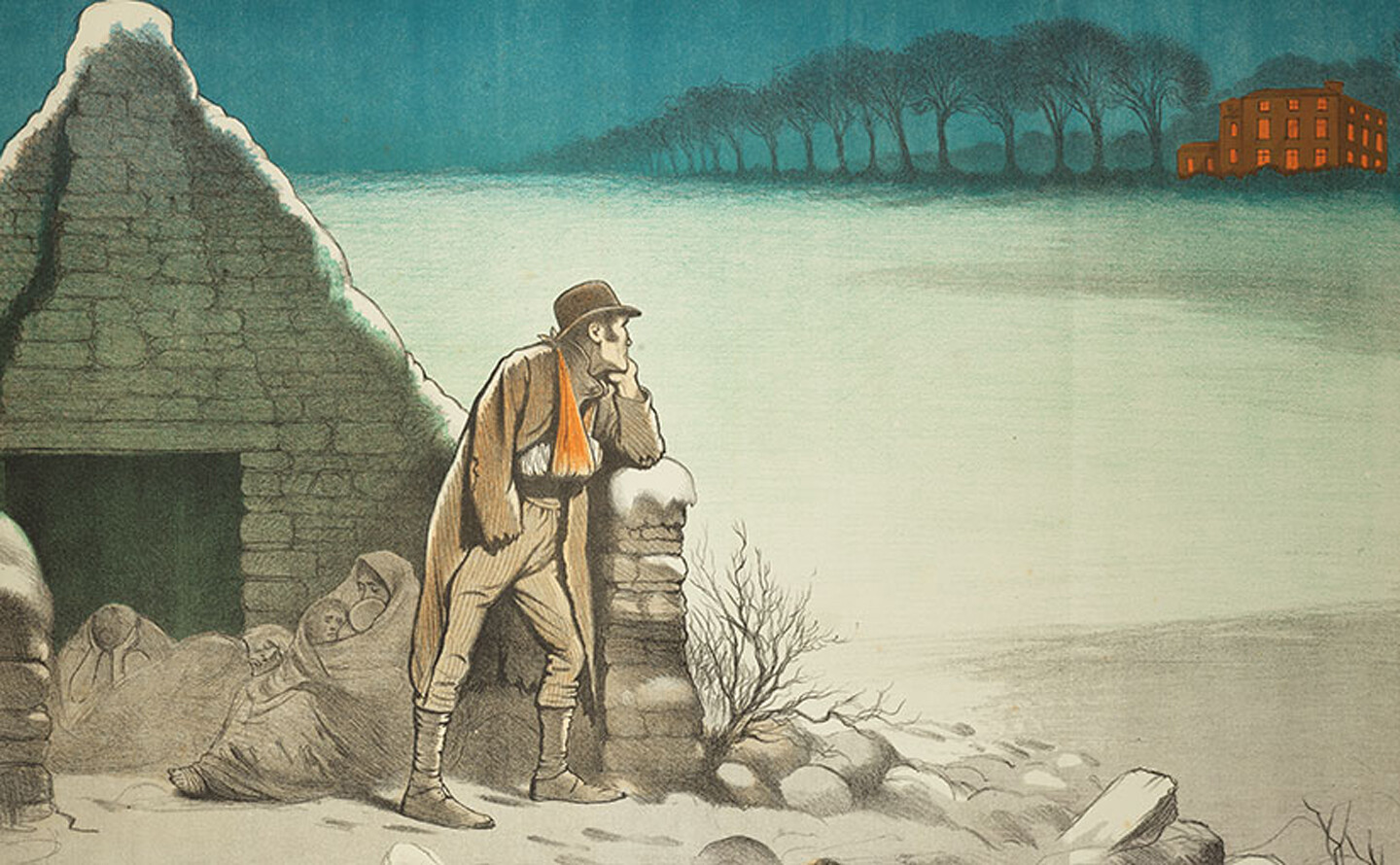

There is a contradiction at the core of contemporary urbanization. Cities and urban regions are expanding rapidly and exert a growing political and economic dominance, but, at the same time, they are steadily cannibalizing their own foundations. Cities are more populous and powerful than ever before, but they are also becoming more unequal, more segmented, less accessible, and less welcoming for all but the very wealthy. Working-class and poor communities provide the labor upon which cities depend, but at the same time they are being expelled from city centers. For new households, new migrants, and others who contribute to urban growth, securing a place in the city is increasingly difficult, and many are forced to improvise on the margins. The age of advanced urbanization is built on an unstable, crisis-prone underpinning.

This self-undermining quality of contemporary urbanization is best illustrated by the struggle for housing, which is a major problem in nearly every big city. Especially, though not exclusively, in globalizing metropolises like London, New York, Hong Kong, Sydney, or Toronto, unaffordable and insecure housing is driving displacement and precarity on a grand scale. Housing and other components of the built environment are becoming increasingly commodified, privatized, and financialized, making them more responsive to the needs of investors and financiers and less attuned to local social conditions and residential needs. Social housing and other partially decommodified alternatives are under attack as states see them as assets to be sold and real estate sees them as opportunities to be seized.

There are many ways to trace the harms caused by the acceleration of commodification and precarity in housing. The approach to political economy known as social reproduction theory can help grasp an essential part of it: not only is housing an unequally distributed consumer good and a globally-traded investment vehicle, it’s also a site of labor in itself. Capitalism could not exist without the constant work of maintaining workers, and much of this happens at home, unwaged. But when housing becomes precarious, the work of reproduction that occurs within it is disrupted. This causes specific forms of misery for households. Social reproduction and its associated networks of care and support are the precondition for all formal economic activity. The neoliberal transformation of the housing system therefore threatens one of the foundational processes that keep urban life going and introduces a force of instability at the core of contemporary urbanization.

Social reproduction is the process of continually maintaining and remaking people, which also entails the continual remaking of labor power, class structures, and society at large. The term originates with the Physiocrats, Enlightenment-era economists who used the phrase to denote the process by which social patterns reassert themselves through economic cycles. Both criticizing and building on earlier usages, Karl Marx generally used the term in a broad sense to refer to the reproduction of capitalist society, even as he recognized the constant reproduction of labor as a challenge that capital, and indeed any economic formation, needs to meet. But the idea of social reproduction has been more fully developed by feminist political economists like Margaret Benston, Meg Luxton, and Lisa Vogel, and especially by intellectuals and activists working within the tradition of autonomist feminism, such as Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Selma James, and Silvia Federici. Social reproduction theory reflects this intellectual heritage as well as practical engagement with Wages for Housework, Black Power, various forms of labor organizing, and other movements and mobilizations that seek to politicize reproductive work.

The basic insight of social reproduction theory is that the realm of production and wage labor is itself produced by particular kinds of labor: the labor of producing, maintaining, and caring for workers, most directly, but also the labor of producing the contexts and infrastructures that make wage labor possible as an institution. As the historian and activist Tithi Battacharya puts it: “If workers’ labor produces all the wealth in society, who produces the workers? … What kinds of processes enable the worker to arrive at the doors of her place of work every day so that she can produce the wealth of society? What role did breakfast play in her work-readiness? What about a good night’s sleep?”1 The work of sheltering, feeding, and supporting workers enables them to get up every morning ready to head to their job and have their surplus value extracted for one more day. Without this labor of caring and maintenance, no economic formation could last.

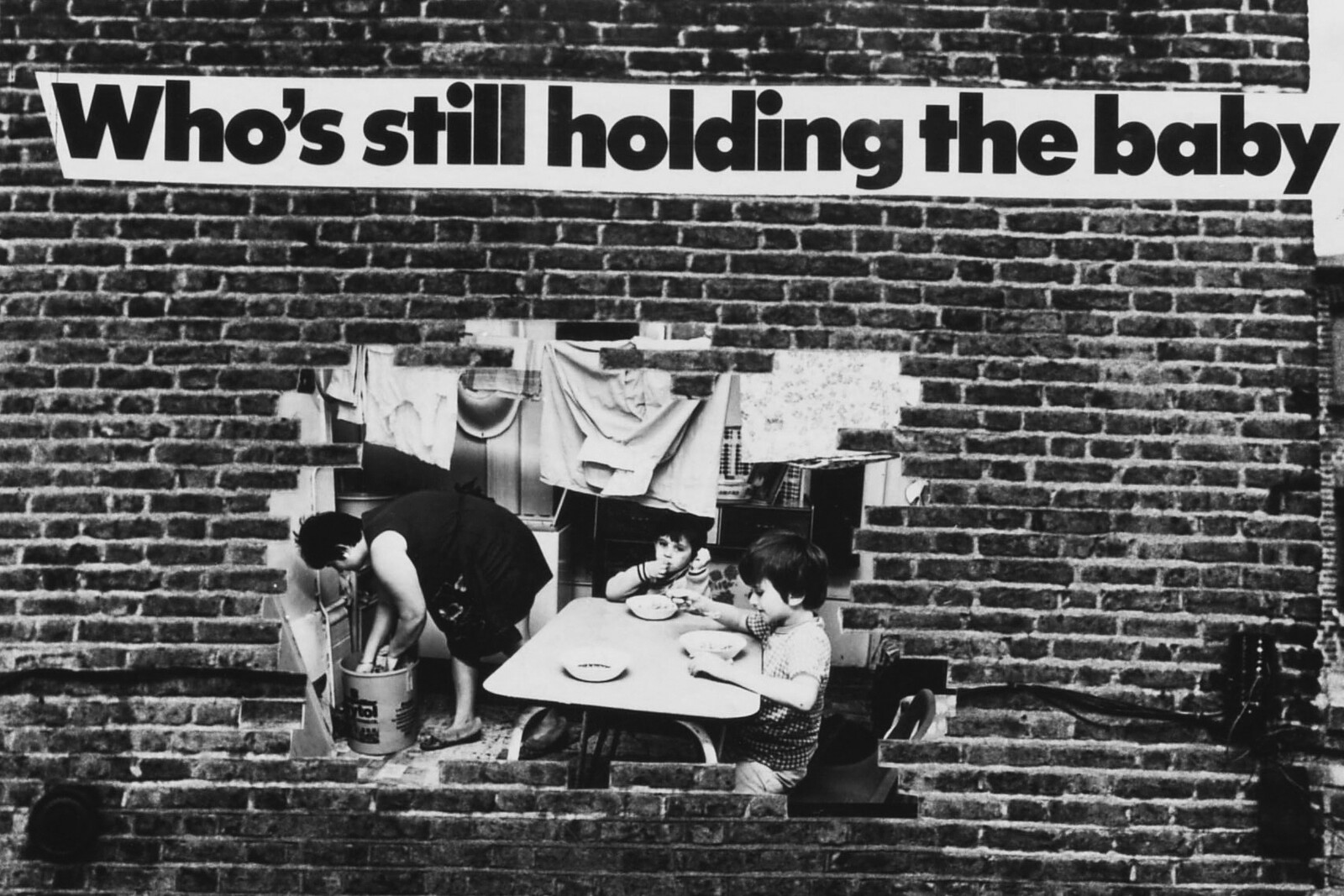

The work of social reproduction is performed in a wide variety of ways—waged and unwaged, formal and informal—and has complex interfaces with other political-economic realms. Whatever form it takes, capitalism in particular, at least insofar as it requires a host of manual, affective, and cognitive skills, cannot exist without the labor of social reproduction. Workers can’t be brought up to participate in the labor market in the first place, much less continuously toil in it for decades, without an extensive infrastructure of care and sustenance. The significance and cost of this work has traditionally gone unnoticed for an obvious reason: throughout most of the history of capitalism, the unending daily labor of social reproduction has overwhelmingly been performed by women as opposed to men, and not infrequently by migrants and people of color. It has been subsumed within patriarchal, nativist, and white-supremacist structures, undervalued and often unacknowledged, and, until recently, often missed by radical political-economic critics.

If economic activity rests on a foundation of reproductive and care work, today this foundation is an increasingly unstable one. What has become known as the “crisis of care” refers to the diminishment of social reproductive capacities and the dismantling of infrastructures of social support.2 In various ways, postwar welfare states did try to socialize some aspects of care and reproductive activity, but as the threads of their safety nets have been unraveled, responsibility for reproduction has been forced back into family contexts, leaving households to fend for themselves. Nancy Fraser, who offers a systematic account of the contradictions of care and capital, describes the contemporary care regime as a “dualized organization of social reproduction, commodified for those who can pay for it, privatized for those who cannot.”3 It’s not that the means of care are disappearing; like so much else today, it’s a matter of unequal distribution and access. Elites are generally able to buy all the care that they need. But for most people, this quotidian but necessary activity is becoming more difficult. The crisis of care is an ongoing source of anxiety and instability in both domestic life and larger-scale economic circuits more generally.

The crisis of social reproduction and the politics of care are inextricably linked to housing. The home is a strategic site for social reproduction: it’s where social reproductive labor happens—not exclusively, but to a significant extent. When housing is overcrowded, poorly maintained, or otherwise inadequate, social reproductive processes are placed under strain. Care requires space, and sufficient domestic space is increasingly hard to come by.

Care also requires time, which is a disappearing resource for working-class and poor households. Insecure tenancies and steadily rising rents mean constantly moving from one temporary lodging to another. The housing problem speeds ahead at a frantic pace, with time marked by cycles of investment and speculation, rent checks and mortgage payments, overdraft fees and eviction notices. This clashes with the steadier rhythms of support and mutual aid. Every time a public housing development is demolished or a household is evicted, some piece of care infrastructure is shattered and needs to be rebuilt at cost. The contemporary city is battered by a relentless churn, which forces households to repeatedly build and rebuild structures and networks of social support.

The atmosphere of the housing system today is one of frenzy. The basic work of making and remaking a household under accelerated, financialized capitalism is exhausting. The daily dramas of domestic life—attending to the specific needs of children or the elderly, keeping up physical and mental health, sustaining relationships and emotional wellbeing, getting oneself and the other members of ones household to where they need to be each day and back again—are becoming, in the words of the anthropologist and feminist scholar Laura Briggs, “impossible stress storms because only a very few of us any longer have the time or resources to do reproductive labor while also earning the wages it takes to keeps us all alive, never mind thriving.”4 These conflicts, she adds, are “where neoliberalism lives in our daily lives.”5

Adding to this exhaustion is the fact that housing is not only a locus of social reproduction, but it is also the object of reproductive labor. Domestic chores, home repairs, fixing the manifold consumer objects that routinely break under flexible consumer capitalism, maintaining neighborhood spaces and institutions: all add to the omnipresent to-do list of necessary reproductive work. And in today’s political-economic formation, they’re increasingly the sole responsibility of households, with no socialized support forthcoming.

An analysis of housing in New York City in 2018 found that more than half of all renter households—and nearly 80% of very low-income renters—were rent burdened, paying more than 30% of their pre-tax income on rent.6 The fact that housing is so expensive today comes with its own particular costs in terms of reproduction and care. When household members need to work multiple jobs or put in extravagant amounts of overtime to pay the rent or make the mortgage, care suffers. Under these conditions, the burdens as well as the joys of care work tend to become unequally distributed. And strategies for finding more affordable housing options often include trade-offs, such as long commutes, that eat into the time available for unwaged activities of all sorts.

Expensive and precarious housing also increases the need for care in the first place. A recent survey by the British housing charity Shelter found that more than one in five respondents had experienced mental health problems stemming from a housing issue.7 Nearly 70% of people who had recently experienced housing problems thought that it had negatively impacted their mental health. Around one sixth of respondents linked housing problems to physical symptoms like nausea, hair loss, and fatigue. The housing problem is driving up the need for care, even as it undercuts the likelihood of receiving it.

For people relegated to the bottom rungs of the urban social hierarchy, the crisis of care is an acute daily reality. For migrant laborers sleeping in bunk-bedded dorms or warehouse workers living in their cars, home has been reduced to the most threadbare form, supplying only a bare minimum of time and space to repose and repair between shifts. Others are forced into care debt, subtracting from the future to meet the needs of the present through financial, physical, and affective means. Millions of households are racking up substantial debt just to achieve some semblance of functional domestic life.8

Plenty of middle-class households also experience exhaustion and “depletion through social reproduction.”9 They may also be spending punishingly large proportions of their income on housing and find it difficult to afford childcare, elder care, or medical care. As a result, they too may feel stress, anxiety, and other symptoms. They may be understood through the notion of “work-life balance,” “burnout,” or some other depoliticized narrative, but they are ultimately manifestations of an underlying political-economic condition. Middle-class households have more of an economic buffer than do their working-class and poor counterparts, but they are not immune to the crisis. Their sense of being drained or squeezed is a consequence of the neoliberalization of everyday life. The best way to channel discontent with this state of affairs is to use it as a basis for cross-class and intersectional solidarities.

Social reproduction theory reveals the unsustainability of contemporary urbanism. It’s not possible for a city to survive for any extended period of time if it only meets the needs of a small, wealthy minority. Even the most abstract financial service work depends upon an infrastructure of waged and unwaged care labor; even unoccupied trophy housing requires ongoing maintenance to keep deterioration at bay. A relative handful of high-wage jobs and so-called high-net-worth individuals cannot keep a city going, to say nothing about questions of justice. Without social-reproductive work the entire edifice will collapse (which suggests that a social-reproductive strike could be an effective form of protest).

Given the crisis of reproduction and care, then, and the evident inability of the housing system to meet the social need for housing, how are contemporary cities still functioning?

One answer is that they don’t actually function. Neoliberal capitalist cities are already in a state of unrecognized collapse, the consequences of which are perpetually deferred only by depleting the social resources of the powerless. It’s not the hedge fund managers who need to take three buses to work. It’s not their progeny who lack childcare and live in a small apartment with multiple other families. The secret of the survival of neoliberal urbanism is that it finds ways to ensure that the least powerful city-dwellers are the only ones who bear the harms that stem from its contradictions. If elites were made to feel the consequences, the political balance of power might well be different.

Another answer is that as much as cities and urban life are harmed in the long run by the crisis of social reproduction, particular strategic actors profit from it in the short run, and endeavor to continuously find small temporary fixes to keep it going. Unmet domestic needs are themselves, predictably, seen as new frontiers of profitability for entrepreneurs in real estate, technology, and other sectors. A variety of expensive solutions are sold as ways to lessen the burden of the crisis of care, such as private childcare facilities in luxury housing developments and digital platforms for vetting and managing nannies. But these are just individualized stopgap measures available to those who can afford them. As long as the basic shape of urban capitalism remains the same, no for-profit innovation will actually solve the problem.

Neoliberal urban society is also still living off of the hard-fought social accomplishments of generations of activists, reformers, and radicals who succeeded in building a public infrastructure of care. This resource—social housing, common spaces, public transportation, social rights, health facilities, and other collective resources—is rapidly being drawn down through privatization and austerity. This devouring must be halted. And a new generation of urban care infrastructure must be created that addresses the specific forms of insecurity, precarity, and depletion found in contemporary cities.

Together, the relentlessness of contemporary capitalist urbanization and the competitiveness of the contemporary housing system are exacerbating and exploiting a crisis of care. If urbanism is to have any kind of viable future, the connections between housing and social reproduction need to be both better understood and radically changed. The housing crisis and the crisis of social reproduction are not identical, but they are firmly intertwined and co-constitutive. Together, they shape urban life itself in a foundational way. The dominant model of urban development creates these crises but is also being undone by them. How these contradictions will play out remains to be seen. They might spur new efforts to use urbanism as a tool for addressing actual human needs and for making life better for the majority of city-dwellers. The alternative is that the contemporary urban political-economic model continues its zombie-like existence, lurching forward, decaying and undead, leaving a trail of destruction in its wake.

Tithi Bhattacharya, “Introduction: Mapping social reproduction theory,” in Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping class, recentering oppression, ed. Bhattacharya (London: Pluto Press, 2017), 1–20.

Ruth Rosen, “The Care Crisis: Working mothers are told to pamper their stress away, but the ‘balancing act’ needs a political fix,” The Nation 284, no. 10 (2007): 11–16; Sarah Leonard and Nancy Fraser, “Capitalism’s Crisis of Care: A conversation with Nancy Fraser,” Dissent 63, no. 4 (Fall 2016): 30–37.

Nancy Fraser, “Contradictions of Capital and Care,” New Left Review 100 (2016): 104.

Laura Briggs, How All Politics Became Reproductive Politics: From Welfare Reform to Foreclosure to Trump (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017), 10.

Briggs, How All Politics Became Reproductive Politics, 10.

NYU Furman Center, State of New York City’s Housing and Neighborhoods in 2018 (2019), 24, ➝.

Shelter, The impact of housing problems on mental health (2017), ➝.

Adrienne Roberts, “Household debt and the financialization of social reproduction: Theorizing the UK housing and hunger crises,” Research in Political Economy 31 (2016): 135–164.

See Shirin M. Rai, Catherine Hoskyns, and Dania Thomas, “Depletion: The cost of social reproduction,” International Feminist Journal of Politics 16, no. 1 (2014): 86–105.

Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture.