Most philosophers—in fact, most people—would agree that use presupposes property; that in order to use something legitimately, one needs the authority to exclude all others from it. For Immanuel Kant, to cite the most philosophically sophisticated justification of private property, the legitimacy of law itself rests on this belief. Kant argues that human freedom is inconceivable without the use of “external objects.” Everyone, therefore, has a rational and rightful entitlement to a universally binding system of rights that ensures ownership over said external objects. In “Doctrine of Right” in The Metaphysics of Morals, Kant defines property as “[permission] to constrain everyone else with whom he comes into conflict about whether an external object is his or another’s to enter along with him into a civil constitution.”1

However, other approaches have contested the axiom of the necessary connection between use and property. For example, in his pamphlet What is Property? the French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon fundamentally attacks the institution of property by advocating the exact opposite thesis: that property is not a condition to use, but an obstacle. “Roman law,” he writes,

defined property—jus utendi et abutendi re sua, quatenus juris ratio patitur—as the right to use and abuse a thing within the limits of the law … The proprietor has the power to let his crops rot underfoot, sow his field with salt, milk his cows on the sand, turn his vineyard into a desert, and use his vegetable garden as a park: are these acts “abuse” or not? In matters of property, use and abuse are necessarily indistinguishable.

—Pierre-Joseph Proudhon2

Today, it is legally permissible (and constantly happens) that owners leave fruit rotting on the stalk or sow salt in the earth. Or, to take more relevant examples, it is possible for homeowners to leave their apartments empty, for banks to withhold food from markets in order to speculate, and for pharmaceutical companies to prohibit poor countries from producing affordable medicine due to patent law. Such phenomena are not accidental occurrences in a decadent society, but rather express the essence of modern property as such. The authority to exclude others from using a thing and thus also from having a say in its use is constitutive of property. The owner has the right to prohibit interference. The right to property authorizes personal caprice and revokes the possibility of external (not just ethical or moral, but perhaps more importantly, legal) intervention.

How exactly should we understand Proudhon’s thesis that the “use and abuse” of property are “necessarily indistinguishable?” Does the abuse authorized by property lie only in a certain inappropriate manner of use? Can there be such a thing as non-abusive use? Is there a particular element that brings property into abuse, and are there means to counteract it? Two influential critiques of property can help explain its abuse observed by Proudhon, as well as point towards the potential for a non-abusive use. The first critique is social, and claims that the problematic aspect of property results from its exclusive character, through which other members of society are excluded from using and deciding on all the resources that are privately controlled. The second is ethical, claiming that the problem with property does not lie in its exclusivity, but already in the appropriation of an object as such. According to this critique, which has its origin in the Franciscan ideal of poverty, an appropriating attitude towards the world leads to an emptied form of subjectivity and intersubjectivity, ultimately incapable of use.

The social critique of property

Private property, as Marx notes in his Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, is “the specific mode of existence of privilege, of rights as exceptions.”3 The nature of private property essentially involves removing something from the community. It is the right to the exclusive use of a thing, thereby excluding all others from using the same thing. Unlike Proudhon, however, Marx does not stop his critique there. He goes on to explain that such a property regime, once it extends to the social means of production, inevitably leads to exploitation. Private ownership of the means of production allows capitalists to appropriate the surplus value produced by others. This leads to the well-known fundamental contradiction between labor and capital: the wealth of society is socially produced, but privately appropriated.

Marx’s focus on exploitation marks a significant shift of emphasis in relation to the thesis of the indistinguishability of property’s use and abuse, which he spells out in various ways.4 The most obvious dimension of abuse is injustice: the sheer fact of exploitation is unjust because it leads to an unequal distribution of both material wealth and social power. The annual study on global inequality commissioned by Oxfam regularly reminds us of the extent of this injustice; according to its 2019 report, the twenty-six richest people on the planet own as much as the 3.8 billion poorest people.5 One does not need a sophisticated theory of justice to recognize the obscene character of such an arrangement, but the most important aspect here is that these twenty-six people are able to remove a large part of the available resources of the world from use by the rest of humanity. Private property is therefore an obstacle to use.

Another dimension of the critique is that of dysfunctionality: capitalism is inherently unstable and crisis-ridden. A system where private parties compete with each other at the pain of their own demise is systematically based on the devaluation of the social, political, and—perhaps most importantly today—ecological conditions of their own success. This, in turn, has devastating effects, even when considering just the consequences of climate change and human-induced natural disasters, which regularly hit the poorest parts of the world the hardest. The abusive character of property is demonstrated here, for example, in relation to the question of sustainability: the dysfunctionality of capitalism has led to a situation in which the current use of natural resources has seriously threatened their future use, or even already rendered it impossible forever.

A third dimension concerns the alienation caused by capitalism. The young Marx in particular tried to show that a society based on the private ownership of the means of production, and thus on exploitation, leads to a deformed, distorted, and therefore deficient subjectivity. Under capitalist working conditions, the worker develops a one-sided, impoverished emotional and intellectual life. This is determined, in Marx’s words, by the fact that in his work he “does not affirm himself but denies himself, does not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind.”6 This critique no longer concerns the objective but the subjective capacity for use. The deformation produced through alienation means that the worker can no longer enjoy even the little she receives in return for her work because, as Marx puts it, in alienated labor she has lost her own self. This oft discredited point of critique (due to its latent essentialism) can be easily substantiated with reference to current socio-psychological diagnoses: phenomena such as depression, exhaustion, burnout, and acceleration show that neoliberal working conditions, which claim to enable self-realization and creativity, are also increasingly undermining a meaningful use of the goods acquired through work.

These three dimensions of the social critique of property concern only private property in the means of production, not property in itself. Every society, Marx claims, has some form of property order; there never was and never can be a society that does not in some way regulate the appropriation and ownership of goods. “True property,” Marx writes, can only exist under communism. Communism will make it possible for proletarians to appropriate what they produce and thus enable them to become owners. Communism, therefore, is not the negation, but the negation of the negation of proletarian property. Max Horkheimer aptly describes this conception of communism as a “gigantic joint-stock company for the exploitation of nature.”7

The social critique of property does not fully exhaust the radicality of Proudhon’s thesis concerning the indistinguishability of property’s use and abuse. Marx aimed to establish conditions of universal usability through common property, but he did not question his bourgeois presupposition of the reciprocal implication of use and property. The unsatisfactory consequences of this adoption of bourgeois premises has been pointed out by critical theory: a classless society conceived like this runs the risk of reproducing the domination of the external and internal nature of human beings, and thus of reproducing deficient relationships to the world and to oneself.8

The ethical critique of property

In his book The Highest Poverty, Giorgio Agamben develops another critical strategy that productively supplements and questions the social critique of property. Agamben reminds us of one of the most important but often forgotten theoretical debates concerning property in the history of Europe: the dispute around poverty within the Catholic Church in the second half of the thirteenth and first half of the fourteenth century. The starting point of this controversy was an eminently theological issue raised by the Franciscan doctrine of apostolic poverty. The Franciscans assumed that Jesus and his disciples did not possess anything at all, either individually or collectively. Thus, as followers of Jesus, the Franciscans also saw it as their duty to live a life without money or any form of property. Hence, the Regula Bullata, composed under the direction of St. Francis himself, states: “The friars are to appropriate nothing for themselves, neither a house, nor a place, nor anything else.” For the Franciscans, poverty was not a matter of economics or politics, but ethics; only a life that in no way enters into an appropriating relationship with the world can be an ethically perfect life. This maxim was provocative, not only because it questioned the secular power and monetary wealth of the Church, but above all because it sought to realize a way of life completely outside any established legal order.

The poverty controversy has a long and fairly convoluted history, with several competing factions, each with various interests and theoretical arguments. In 1245, the pope claimed ownership of all Franciscan properties, thus allowing the friars to use them without technically owning them. According to one of the most important Franciscan theologians, Giovanni di Bonaventura, the friars rejected not only some property rights, but all rights to objects in general, and limited themselves to simple de facto use (usus facti or usus simplex). Another Franciscan theorist, Bonagratia di Bergamo, tried to make this de facto use plausible with an analogy to animals: when a horse eats its oats, it does not first have to claim ownership over them; rather, its simple use is completely indifferent to and incommensurable with the juridical order of property.

This Franciscan practice and the papal worldview eventually became too heterogeneous for peaceful coexistence. A direct confrontation finally broke out between the friars and the Holy See when Pope John XXII, who firmly opposed the view that Jesus and his disciples were completely without possessions, took over the pontificate in 1316. With his 1322 bull Ad conditorem canonum, John XXII revoked the ecclesiastical administration of Franciscan possessions, effectively forcing the friars to become legal owners of all the things they wished to use. The Pope also declared the Franciscan ideal of poverty heretical, thus driving the most important members of the order into exile.

“What is in question, for the order as for its founder,” Agamben concludes, “is the abdicatio omnis iuris (‘abdication of every right’), that is, the possibility of a human existence beyond the law.”9 These efforts to remain outside the law appear rather counterintuitive, considering that many political conflicts today are about equal inclusion under the law. Hannah Arendt speaks prominently of a “right to have rights,” i.e. a (pre-juridical) right to be part of a political community and to participate in its social practices.10 Yet a problem just as significant as exclusion from the political community is the phenomenon of forced inclusion, that is, the imposition of a legal or political order against someone’s will. Against such forced inclusion, the Franciscans insisted on their right not to need rights.11 Although it seems at first that no one can be harmed by being granted legally secure control over the things they need to satisfy their fundamental human needs, from the Franciscan perspective, John XXII’s bull must have appeared as an act of violence. The act seriously damaged the Franciscans’ ability to self-determination, because it turned them into subjects they simply did not want to be.12

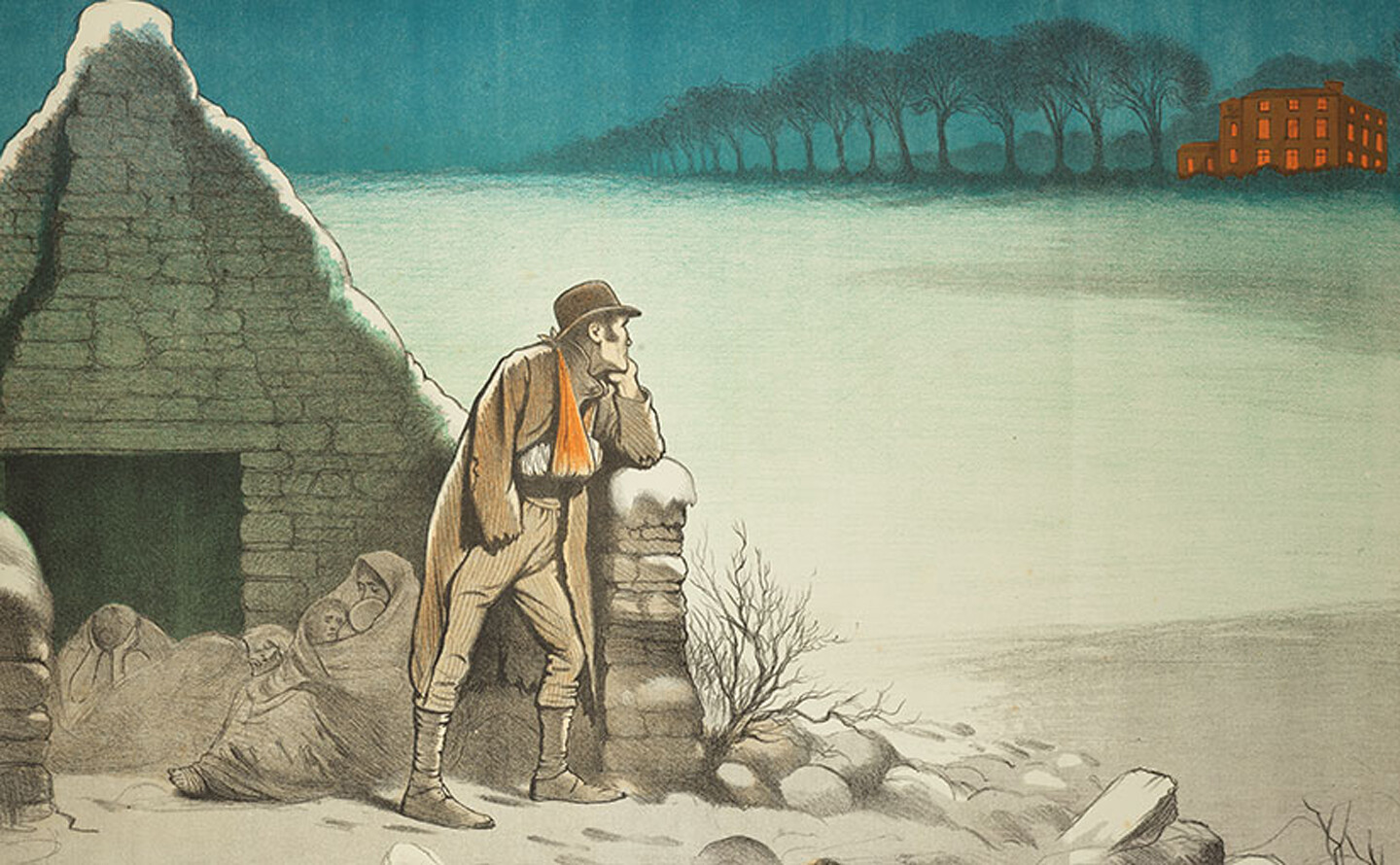

The Franciscans’ conviction that an ethical life is only possible when one does not become a legal subject is not just some religious quirk. The problem of forced inclusion becomes obvious in the case of colonization, within which European states succeeded in extending the Roman property regime to the entire planet and thus eliminating the possibility of living without property (rights) without also falling into deep material need. The violence inherent in this does not (only) consist of a violation of law (although it is regularly accompanied by this), such as breaches of treaties, expulsions, and physical violence, but rather lies deeper, encompassing the implementation of a normative order within which property conflicts can be conducted at all; i.e. in the establishment of law as such.

The colonial order often forces indigenous populations to relate to their environment as their property in the first place. Such an involuntary imposition of a legal order therefore constitutes a form of violence, even if it does not involve taking away anything materially from those affected. Rather, the violence of law consists in damaging the ethical substance of an autochthonous community by coercively transforming it into an alien social grammar, and thus devaluing preexisting knowledge and local practices. In some cases, opposition to such a conversion may have mythical or religious reasons, while, in others, the prevailing views of the tribal community or traditions are more important. But, in every case, the establishment of a property order is accompanied by a fundamental intervention in the affected parties’ relationships between themselves and the world. This means, among other things, that under colonialism, members of indigenous groups were forced to transform their subjectivity into that of legal persons—especially in order to defend themselves precisely against that colonization.13 In turn, socializing institutions were set up to manufacture legal subjects in the first place. The colonial experience thus cannot be fully grasped without the theoretical instruments of a social critique of property alone.

In addition to the general commitment to keep open the possibility of a life beyond law, and against the internal and external expansions of right, the Franciscans also developed a particular critique of property in terms of content, one whose philosophical significance and political implications have still not been fully appreciated. While the debate between the Franciscan theorists and curial jurists gravitated around the highly specific theological question of whether Jesus and the apostolic community lived completely without property, it has implications that extend far beyond the realm of theology.

As Annabel Brett recognizes, the ideal of poverty is by no means just about poverty—the Franciscans could have remained poor within the existing legal order and lived in peaceful coexistence with church and society. Rather, the friars wanted to develop a subjectivity opposed to power, empire, and mastery.14 What they lacked, however, was a sufficiently large imaginary of concepts and images to outline such an anti-sovereign subjectivity. Initially, Franciscans were instructed to simply occupy a position opposite to domination, namely the subject or slave, as the safest measure to not become masters themselves. But Franciscan ethics seem to open up other possibilities beyond a humble resignation to fate.

In addition to the metaphors of submission, the concept of “minority” is essential for Franciscans. Franciscans are minorities, or Friars Minor, and, from a purely legal point of view, like children. Just as minors are under the guardianship of their parents, so are Friars Minor under the guardianship of the Church.15 This acceptance of the minoritarian position also seems at first like a simple inversion of the terms of domination: instead of sovereigns, they want to be subjects; instead of fathers, children. Yet the idea of valuing and practicing a minoritarian perspective has different theoretical and practical implications than simply valorizing subaltern positions. Minoritarian perspectives open up new possibilities for action, as Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari have shown. Becoming minority here refers to the affective engagement that creatively resists the temptation, the desire, to dominate others, including that of the revolutionary.16 From here it is only a small step, following the Franciscans, to identify poverty as a prerequisite for democracy. If one understands the people (in the sense of plebs or multitude) not simply as the self-identical subject of popular sovereignty, but as the “part with no part” for whom the distance to domination is always already subjectively inscribed, then it becomes clear that real democracy can only be determined as the government of minorities.17

Another, more speculative and experimental point of property’s ethical criticism concerns the impossibility of “true” use under the auspices of law. One of the few treatises of the time that deals directly with the advantages and disadvantages of different ways of handling material goods—that is, without a detour through legal-philosophical or theological discussion—was written by the Conventualist wing of the Franciscans to illustrate the negative psychological effects of property. For the Conventuals, the figure of the miser expresses the true essence of property, for the miser loves to have something but not use it. Better still, the more the miser loves his riches, the less he dares use them.18

For the millionaires and billionaires produced by today’s global order of inequality, it has become completely impossible to use everything they own. Yet miserliness is not a privilege of the rich. Rather than Scrooge McDuck and his money bin, the miser is represented by the normal “honest man of recognized credit,” whom Max Weber cites to support his analysis of the essentially Protestant “philosophy of avarice” as one of the main characteristics of the spirit of capitalism. According to this ideology, violations of the maxims of thriftiness, i.e. abstinence in the use of one’s own wealth, are no longer regarded as personal folly but as an ethical breach of duty, and are sanctioned accordingly.19 That is to say, capitalism produces social wealth only by producing at the same time a mentality and affective structure that renders taboo and devalues the enjoyment of this wealth.

In light of today’s culture of affluence, which is hardly marked by a Protestant ideal of asceticism, a different approach must be taken in order to prove the general unusability of produced goods. Especially in light of the decadent wastefulness of late capitalism, Agamben claims that one can no longer even enjoy the things consumed in consumption.20 Agamben’s remark does not go beyond this brief suggestive call for a critique of consumption, yet it could be easily complemented with a wealth of material from cultural criticism. The commodity fetishism of today’s consumer culture seems to coincide strangely with a simultaneous disregard for the product. On the one hand, commodities are becoming more and more libidinally infused, while, on the other, their lifecycles seem to be getting shorter and shorter. In a Marxist vocabulary, this means that the use values of commodities are increasingly becoming consumed by their exchange values.

Like the social critique, the ethical critique of property has its own problems and limitations. It is no coincidence that the Franciscan experiment did not last, and was ultimately defeated by the Curia, both practically and philosophically. In the language of Nietzsche, the Franciscans are characterized by an extreme slave morality.21 They withdrew from law but could not establish an alternative way of using the potencies available in the world. Thus, their retreat from law is at the same time a retreat from the possibility of influencing the course of the Western history of being. The social and ethical critiques therefore mutually point out their respective blind spots. The ethical critique deciphers the fundamental damage that the paradigm of appropriation inflicts on our relationships to ourselves and to the world, while the social critique enables us to think of an alternative use of the enormous wealth and multitude of possibilities that capitalism has produced up to now.

For a political critique of property

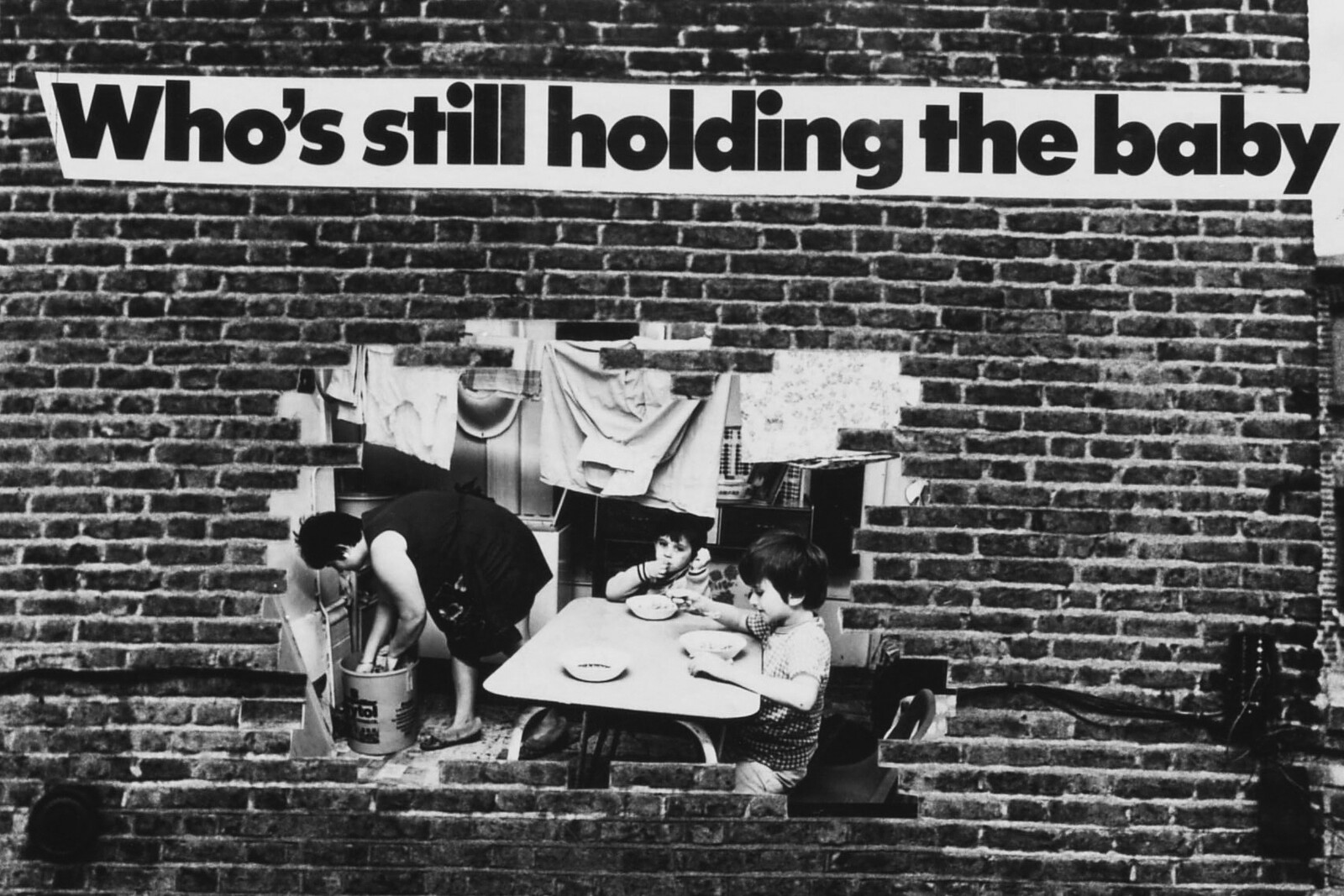

Registering the failure of their critique, Agamben claims that Franciscans should have advocated for the creation of general social conditions that would allow them to “make use of things without ever appropriating them.”22 Such a critique manifests itself paradigmatically in the practice of squatting: the squatter uses a building or territory without ever owning it. She profits from the potential invested in a given structure without entering into a relation of appropriation with it. Her treatment of the squatted building or land is also inherently gentle or even restorative, creatively challenging the prevailing link between property and abuse with a new link between occupation and use. This practice is not simply social or ethical, but political insofar as it seeks to confront those who wish to maintain exclusive control over their property and whose power and wealth is therefore threatened by precisely such action. The squatter revokes the owner’s private caprice and forces her to give at least a basic general justification, which can only be achieved through communication and democratic deliberation. While the social critique of property aims at expropriating appropriation, and the ethical critique at non-appropriation, the political critique aims at ex-appropriation, that is, at establishing conditions under which no one can exclusively appropriate the world anymore.

The example of squatting as a practice of the political critique of property can be generalized. This is one of the promising aspects of the current debate on the commons: it allows us to escape the limits of the Western property tradition and instead to see property no longer as a condition but an obstacle to the common use of shared resources.23 This becomes obvious in the example of open-source software, in which programmers challenge the dictates of exclusive property rights, such as copyright and patents, and work cooperatively on a common project. The goods produced in this way are not only freely available and thus usable for everyone, but are also often of better quality, which means they are better to use.

Commoning is not limited to immaterial goods. The commons were put on the agenda with the Zapatista uprising in 1994, which fought to preserve an article in the Mexican constitution that made guarantees to individual communities that part of the land must remain in the form of commons, that is, in public ownership.

The knowledge gained in open-source software, therefore, that common and free cooperation not only creates better working conditions but also better results, can be transferred to the field of hardware. While the production of commodities under conditions of market-mediated competition of independent private labor is fundamentally oriented around exchange value (production for exchange), commons-based production can be oriented around use value (production for use).24 In this way, products can be produced that are attractive to users not only because they are actually free, but also because they last longer, have fewer safety defects, and are generally better at meeting their needs.

Today, struggles over commons encompass many areas of public infrastructure, such as free access to basic needs, including general access to land, water, and air, as well as public duties such as education, healthcare, and more far-reaching struggles for social welfare including free public transport, swimming pools, sports facilities, and cultural institutions.

The commons operates within given legal systems. It is not an anarchic structure. Above all, the commons often sees itself as a form of common property (in contrast to private and state property). However, these legal forms often have only a strategic and thus provisional character. Constructs such as the Creative Commons License serve only to prevent private appropriation of the corresponding product and to guarantee that it remains in the public domain. The Creative Commons License is a property right that simultaneously pushes the idea of property rights as such to its limits and undermines it; it serves solely to ensure the general conditions of non-appropriability. Commoning thus unites both the social and ethical critique of property. The commons makes it impossible to privately appropriate what is socially produced, thus blocking exploitation and related forms of injustice, dysfunctionality, and alienation.

At the same time, the commons does not simply aim at an alternative form of appropriation through common property, as was the case with the social critique, because commons-based production is not universalizing. It is prescribed neither by state nor economy, but rather allows an exit from those state and economic dictates. It also renders impossible both the development of an imperial possessive individuality, as well as the fetishization of consumer goods. At the level of subjectivity, there is much more reason to hope that the non-egoistic coordination and cooperation practiced in commons can mobilize or cultivate quite different affective-habitual resources than would necessarily be the case under capitalist competitive conditions. Commons thus seem to correspond exactly to the demand to use the world without appropriating it.

Epilogue

In the aphorism “Refuge for the Homeless” in Minima Moralia, Theodor Adorno develops the famous verdict that the wrong life cannot be lived rightly. He derives this from a moral paradox in regards to modern dwelling:

It is part of morality not to be at home in one’s home. This gives some indication of the difficult relationship in which the individual now stands to his property, as long as he still possesses anything at all. The trick is to keep in view, and to express, the fact that private property no longer belongs to one, in the sense that consumer goods have become potentially so abundant that no individual has the right to cling to the principle of their limitation; but that one must nevertheless have possessions, if one is not to sink into that dependence and need which serves the blind perpetuation of property relations. But the thesis of this paradox leads to destruction, a loveless disregard for things which necessarily turns against people too; and the antithesis, no sooner uttered, is an ideology for those wishing with a bad conscience to keep what they have.

—Theodor Adorno25

The aporia described by Adorno is only aporetic because he did not (yet) know the practice of squatting. Squatting opens up the possibility of updating and expressing exactly what Adorno pinpoints: “that private property no longer belongs to one,” but without however falling into paralyzing “dependence and need.” The moral imperative of “not being at home in one’s home” is thus rehabilitated as a political imperative. It cries: Occupy.

Immanuel Kant, The Metaphysics of Morals, in Immanuel Kant, Practical Philosophy, ed. Mary Gregor (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 256 (§8).

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, What is Property? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 35.

Karl Marx, “Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right,” Marx & Engels Collected Works 3 (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1975), 109.

The distinction between the three dimensions follows the proposal made in: Rahel Jaeggi, “What (if anything) is wrong with capitalism? Three approaches to the critique of capitalism,” Southern Journal of Philosophy 54 (2016): 44–65.

“5 shocking facts about extreme global inequality and how to even it up,” Oxfam International, ➝.

Karl Marx, “Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844,” in Marx & Engels Collected Works 3, 274.

Quoted in Theodor W. Adorno, Lectures on Negative Dialectics (Cambridge: Polity, 2008), 58.

Admittedly, there are also passages in Marx that are more compatible with the ethical critique of property outlined below. For a generous reading of Marx, see John Bellamy Foster, Marx’s Ecology: Materialism and Nature (New York: Monthly Review, 2000).

Giorgio Agamben, The Highest Poverty (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013), 110.

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (New York: Harcourt, 1973), 296.

Werner Hamacher coined this phrase, before Agamben’s rediscovery of the Franciscans; see Werner Hamacher, “The Right Not to Use Rights: Human Rights and the Structure of Judgments,” in Political Theologies, eds. Hent de Vries and Lawrence E. Sullivan (New York: Fordham, 2006).

For a trenchant critique of contemporary subjectivities as marked by the property regime, see Eva von Redecker on phantom possession: Eva von Redecker, “Ownership’s Shadow: Neo-Authoritarianism as Defense of Phantom Possession,” Critical Times 3, no. 1 (April 2020): 33–67.

On the anticolonial critique of property, see groundbreaking interventions by: Brenna Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018); and Robert Nichols, Theft is Property! Dispossession and Critical Theory (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019).

Annabel Brett, Liberty, Right and Nature: Individual Rights in Later Scholastic Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 12.

Compare Agamben, The Highest Poverty, 111, 125.

Compare Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 105–6.

Jacques Rancière, Hatred of Democracy (London: Verso, 2006); Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Commonwealth (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 44.

Agamben, The Highest Poverty, 129.

See Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (London: Routledge, 1992), 7.

For him, the true essence of the concept of property only reveals itself in mass consumption: today’s products can no longer be used, and property rights only lead to abuse. See Agamben, The Highest Poverty, 131.

Compare Friedrich Nietzsche, On The Genealogy of Morals (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967), 22.

Agamben, The Highest Poverty, 144.

See, for example, Silvia Federici, Re-enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons, (Oakland: PM Press, 2018).

For a convincing argument on transferring the principles of peer production to the material economy, see Christian Siefkes, From Exchange to Contributions (Berlin: Edition C, 2007).

Theodor W. Adorno, Minima Moralia (London: Verso, 2005), §18.

Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture.

Category

This text was translated from the German by Jacob Blumenfeld, and is a summary of some of the central arguments from the book Der Missbrauch des Eigentums [The Abuse of Property] (Berlin: August-Verlag, 2016).

Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture.