Historically, the idea of home has mirrored a faithful image of society’s deeper social structures. Consequently, housing has often been used as an effective tool for the ideological construction of power relations. Albeit traditionally thought of in the west as a protective apparatus against externalities, by serving as a vehicle for the capitalist division of productive and reproductive labor, the archetype of the home has played a central role in the creation of gendered relationships within domestic and social spheres.

The apparent refuge of the home is inseparable from the immense economical, technological, and political structures that produce it. In particular, the technological changes fostered during the industrial revolutions have transformed not only the way housing has been designed, but the way it is seen and who it is meant for. Its development throughout the past two centuries has reinforced hetero-patriarchal asymmetries and increased the commodification of everyday life.

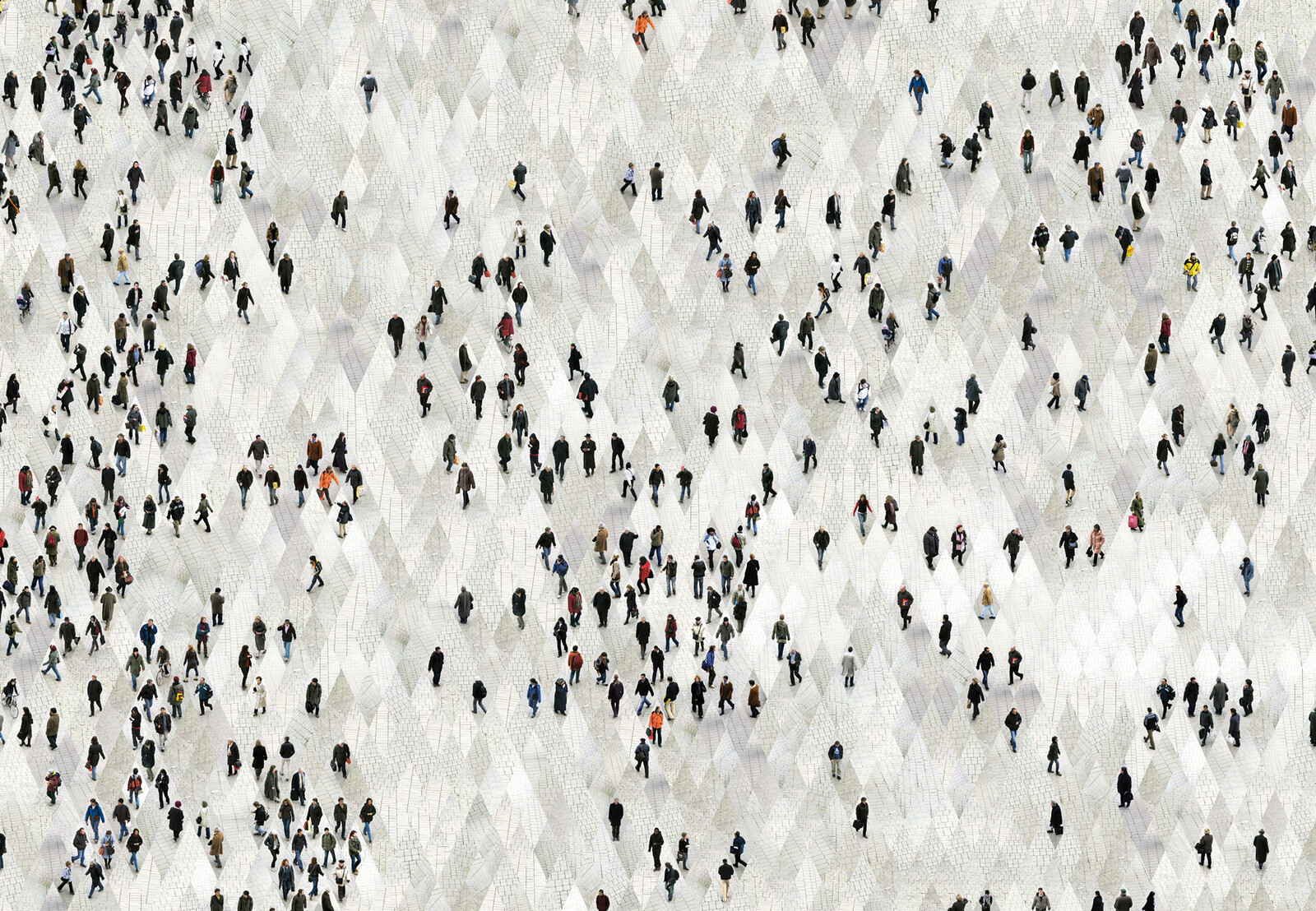

Today, due to the liquified structures and technologies of late capitalism, the limits of the domestic sphere have become blurred. Increasingly, our houses connect to a vast and growing digital sphere. This invisible territory into which our homes and the lives we live in them advance has turned the entirety of the built environment into an endless domestic landscape, one defined less by buildings or public spaces and more by objects and technologies. With the design of these new domestic apparatuses, notions of privacy and publicity, as well as productive and reproductive labor, are being dramatically redefined. Gradually, the home has become a diffuse entity, one supported by different services and spaces that do not necessarily occur within the same bounded domain. The home of today is where the domestic and the urban, labor and leisure, private and public, all converge into an enigmatic and problematic entanglement.

Historical and conflicting definitions of productive and reproductive labor shape domestic architecture and its related economies in different ways. Describing reproductive labor and its effects on both bodies and architecture can not only reveal how the relationship between space and gender has evolved alongside social and economic systems, but also provide crucial entry points for critically engaging with and reimagining the present.

Georg Friedrich Kersting, Woman Embroidering, 1811. Source: National Museum in Warsaw/Wikimedia Commons.

The Spatial Division of Productive and Reproductive Labor

Marx characterized the transition from feudalism to capitalism as a process of primitive accumulation: the progressive concentration of land and the emergence of the independent worker. But, as Silvia Federici recalls, the transformation from feudalism to capitalism not only requires the transformation of the body into a wage earner—a free laborer, independent from the land and predisposed as his own means of production—but also the submission of women for the reproduction of the workforce.1

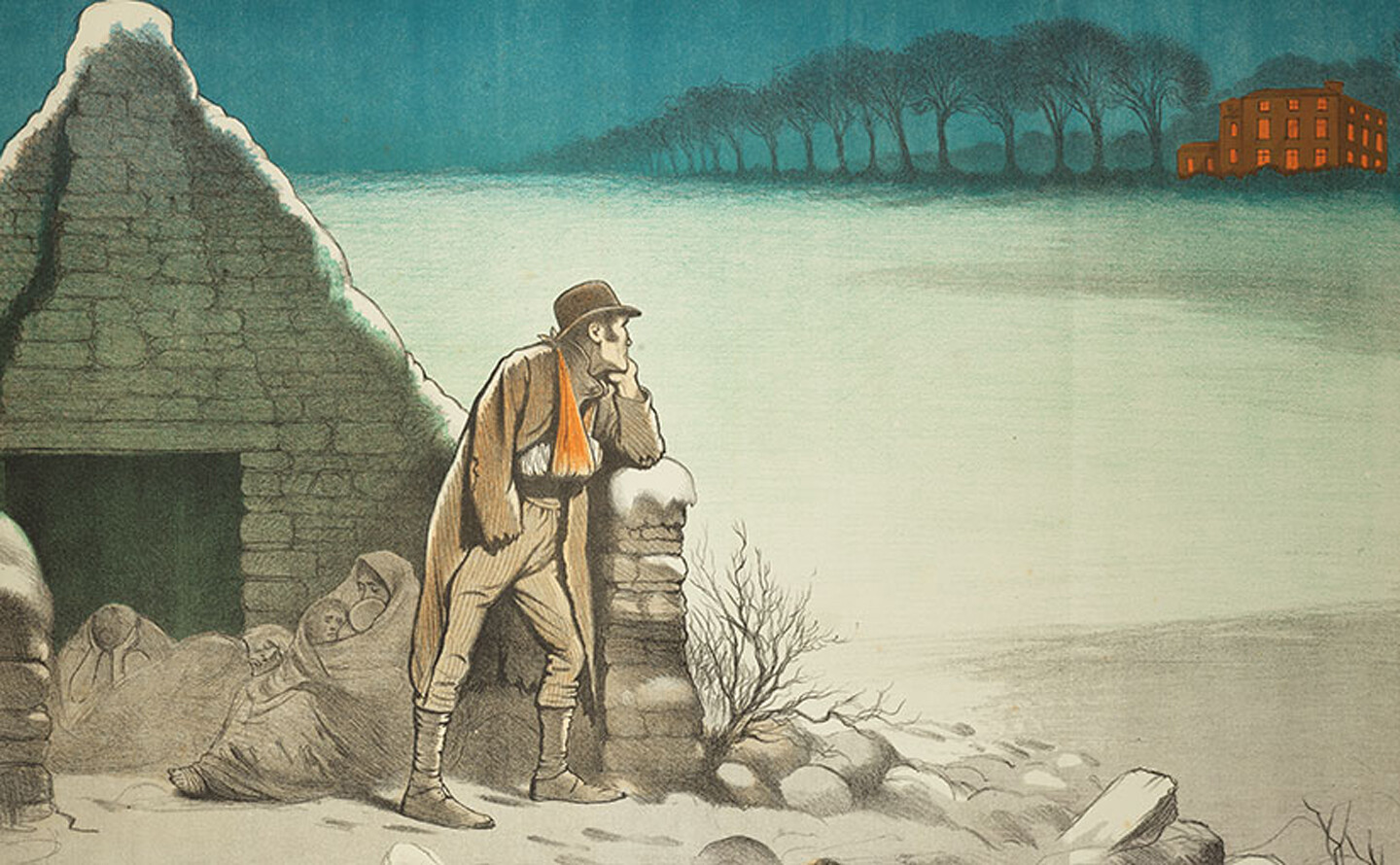

In this sense, primitive accumulation requires not only the accumulation of goods, but also the accumulation of differences and divisions within the working class, in which hierarchies built on gender, race, and age become constitutive of the proletariat. Amidst and in the image of this, the idea of the home was gradually built, dividing and progressively separating the productive workspaces occupied by men from the spaces of domestic reproduction, occupied by women.

Throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, homes were steadily stripped of and detached from workshops, stores, and other similar “productive” spaces. This followed a wider process of zoning and categorization that eventually crystallized in the advent of the modern, functional city plan. As the idea of the home became detached from direct economic production, it started to be understood as an extension of the female body, and therefore redefined as a place of care.

Diagrams of an inefficient and efficient kitchen, from Christine Frederick’s 1919 book Household Engineering. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Wellcome Library London.

Home, Gender, and Industrial Revolutions

Each industrial and technical revolution has had its effects on the definition of the home and the relationship between productive and reproductive labor. During the first industrial revolution, the space of reproduction was progressively segregated from the space of production. Mass housing—a then-novel phenomenon that arose in response to the centralization of the workforce in factories—divided and redistributed labor along gendered lines.

From the mid-nineteenth to the twentieth century, new forms of energy boosted the technification of the house and turned it into a space for efficient housekeeping. During this period, Taylorism and other productive methods derived from mass production and economies of scale were implemented in the home. Although productive labor remained detached from the domestic sphere, its ideology of efficient production was progressively introduced to the household. At the beginning of the twentieth century, for instance, “domestic engineering” emerged as a movement and spread a belief in the potential for imminent liberation from domestic constraints and a radical reduction of chores, all thanks to salvific technology.

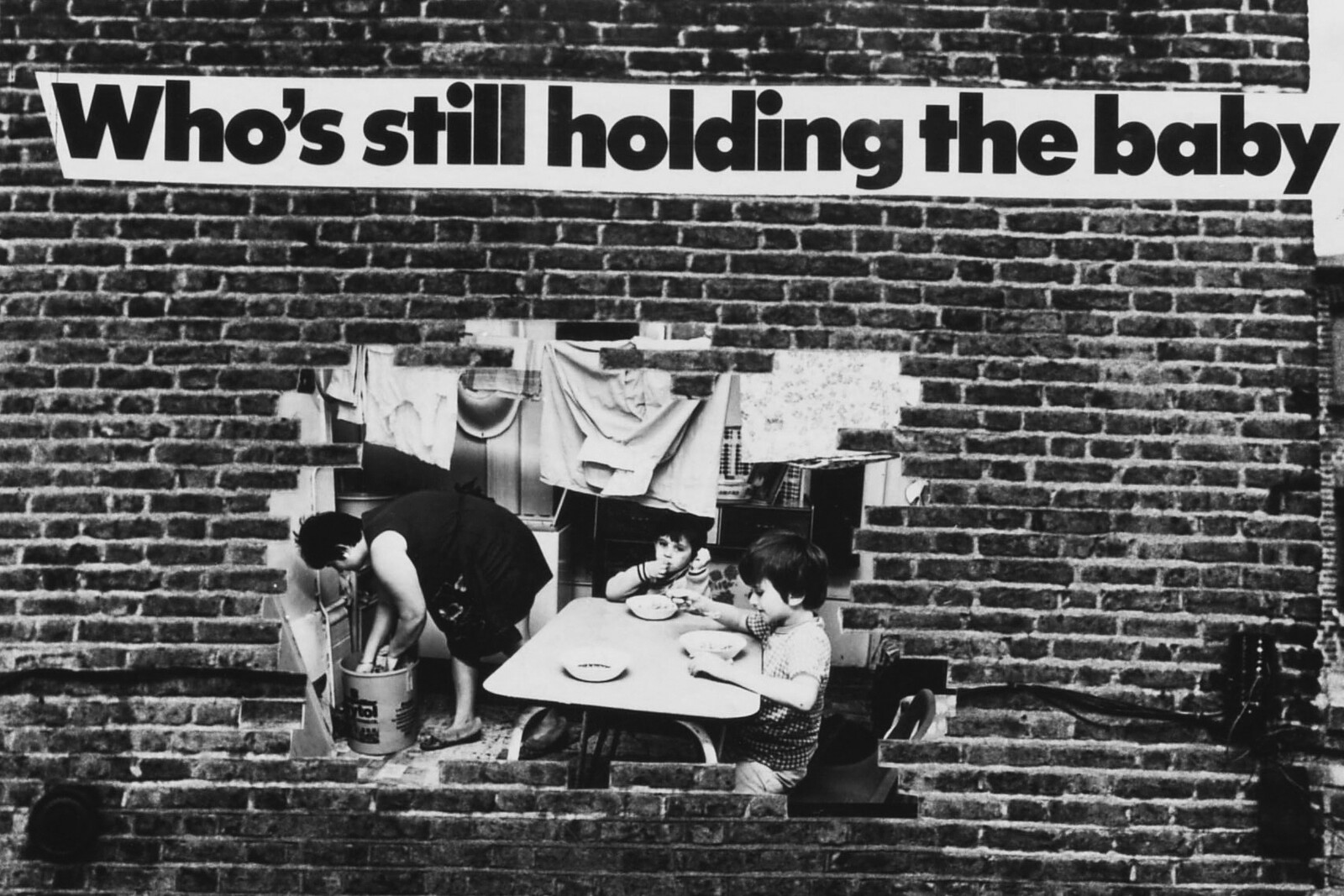

The engineering of the home was concurrent with the progressive inclusion of women into the labor force, particularly during the two world wars, when men were mobilized to fight and women were called upon to fill their job vacancies. In order to overcome the incompatibility between housekeeping and business hours, new, “magic,” almighty devices for the modern house were developed and used. Such domestic technologies sold the idea of reproductive labor not as a burden but as an effortless, light, and even desirable activity. While reconfiguring and reinforcing the heteropatriarchy of the home, from then onwards, women allegedly became able—and thus expected—to undertake both forms of labor—productive and reproductive—at once.

During those years, many articles were published about Christine Frederick’s domestic scientific methods as a doubled-edged attempt to provide women with the opportunity to earn a “domestic engineering” degree. While trying to elevate the category of housework to a science, it also tried to normalize and standardize its inequality. As Dolores Hayden points out, domestic engineers’ work fell into an unsolvable contradiction: they tried to apply scientific methods based on the division of work and specialization, but only on a single person; relying on the housewife as the sole keeper of the house made such a division of work impossible. With this contradictory promise, productive and reproductive labor started to converge under a highly biased gender asymmetry.

Blurring the Limits

With the spread of broadcasting technologies in the mid-twentieth century, new domestic media became central to the biopolitics of the home.2 The normalization of radio and television was, however, only the beginning of the transformation of the domestic realm into one of multimedia production and control. With the interconnection of interior spaces, the idea of privacy—so commonly associated with the domestic—started to mutate and, along with it, all other binaries that once defined the idea of modern life.

The hyperconnectivity of homes today allows us to understand new forms of domesticity. The diffuse house is one who’s physical and immaterial limits do not match. Digital technologies have changed the way we live in our homes and created new ways of belonging, behaving, and relating to others.

Not that long ago, families would regularly gather around the TV. Today, however, a new social reality is emerging with the atomization of devices and the increasing demand for services and spaces. Programmatically speaking, on both urban and domestic scales, different uses and functions have begun to merge. The house is no longer just an unchanging space for our belongings and a space for care. Instead, it is a transient, productive, and networked space that can—and must—answer to whatever need arises.3 As Paul B. Preciado has recently claimed:

Well before the appearance of Covid-19, a process of global mutation was already underway—we were undergoing social and political changes as profound as those that transpired in early modernity. We are still in the throes of the transition from a written to a cyber-oral society, from an industrial to an immaterial economy, from a form of disciplinary and architectural control to forms of microprosthetic and media-cybernetic control.4

The nature of the house today is cybernetic. Productive and reproductive labor, the spaces in which they take place, and the bodies that carry them out, are once again being reshaped and redefined.

Digital platforms allow people not only to work from home, but also to market themselves, their possessions, and their services online with ease. In this sense, houses have become urban. In certain circumstances, this realignment can contribute to new symmetries, new forms of reconciliation, and reduced demands on energy and time. In others, however, it only makes more visible the precarity upon which daily life depends.

Indeed, these new social patterns and economic logics have flourished online without regulation, and have often only furthered patriarchal-colonial and extractivist regimes. Contemporary domestic economic practices that defy the business model of traditional companies, from renting rooms to selling meals online, are endlessly debated and discussed while labor rights continue to erode and wealth continues to be concentrated.

With the emergence of the diffuse house, urban infrastructure is increasingly being shaped by domestic spaces. At the same time, domestic spaces have been forced to become more generic, reprogrammable according to the ever-changing demands of capital. Reproductive and productive spaces are reuniting once again. While this may have been heralded by a slew of contemporary crises, anxieties, and breakdowns, the new technologies that have brought this about in the first place still might allow new social and economic structures to emerge. The only question is how to use them to reestablish and redistribute power.

Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation (Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 2004).

Paul B. Preciado, Pornotopia (New York: Zone Books, 2014).

Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (London and New York: Verso, 2013).

Paul B. Preciado, “Learning from the Virus,” ArtForum, April–May 2020.

Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture.

Category

Thanks to Guillermo Lopez for his thoughtful comments.

Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture.