We will never again shout, sneeze, or cough unmasked without provoking anger and fear. We will never again hug each other without the thrill of shared danger. We will never again approach a street corner without awaiting potential murder. Even when the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is over, we will never forget that breath and touch can turn into lethal weapons—at least for the sick and the elderly. To overcome that feeling we will avoid them altogether.

Or will we? The AIDS crisis in the 1980s tells us quite the opposite. Many continued to have unsafe sex even though an HIV infection was expected to be fatal. It often didn’t even feel like playing with fire. It was just a bit more pleasurable, a bit more intimate. HIV also didn’t increase the discrimination of gay, bisexual, or highly promiscuous people. If anything, HIV made them more visible and normal.

Then again, different from SARS-CoV-2, it is completely safe to interact with people who are HIV positive in all ways except for “unsafe” sex. And even now that there is a reliable treatment to prevent AIDS, sex rates are steadily going down all over the world. People are hooking up more casually and are more reserved about sex. Sex is gradually losing importance. Obvious reasons could be improving masturbation devices, free porn, virtual sex, less urge to reproduce, less urge for a steady partner, and an increasing number of alternate joys and distractions.

These reasons could also make us avoid physical closeness altogether. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic could work as an exercise in social distancing that will prevail when the danger vanishes. Did most of us comply rather easily to self-isolation because—wittingly or unwittingly—we had been waiting for this opportunity? Different from our sex rate, our spatial proximity rate has never been researched comprehensively.

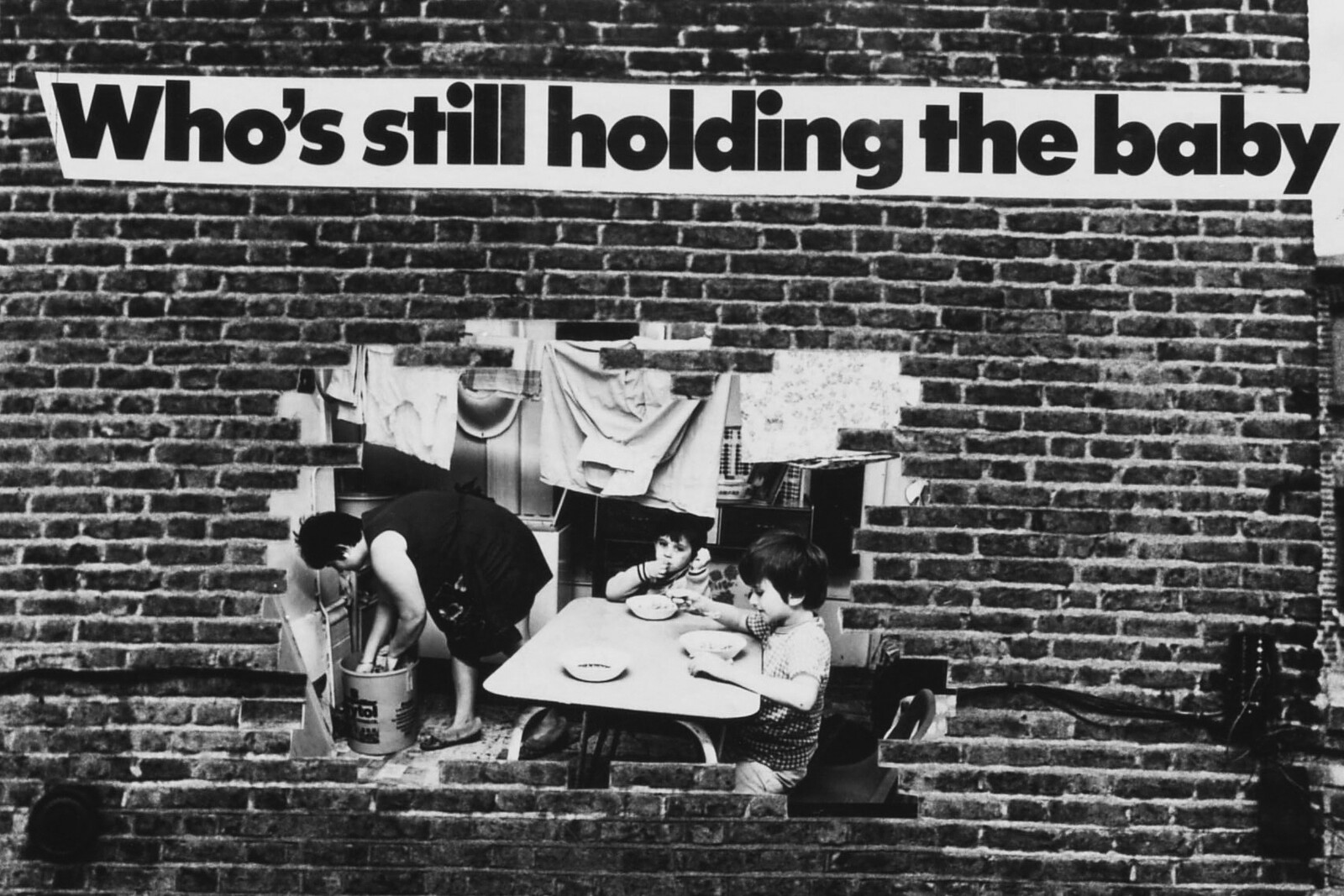

While we continued to congest further and further in streets, public transport, planes, or beaches, it was nothing that we thrived for. While we still frequented stadiums and clubs, sitting and VIP areas were growing. Public spaces were privatized to guarantee some exclusivity. Major political debates shifted from the question of proper distribution to the question of proper distance: from neo-nationalism, neo-protectionism, and mass incarceration to environmental protection and safe spaces.

In the 1980s, trend forecaster Faith Popcorn coined the term “cocooning,” describing it as the “rapidly accelerating trend toward insulating oneself from the harsh realities of the outside world and building the perfect environment to reflect one’s personal needs and fantasies.” Many phenomena she observed back then are still evolving today: gated communities, soft furniture, home cinema, home office, home delivery. Popcorn understood cocooning as a sign of political disengagement. But different from the bourgeois Biedermeier style from the early nineteenth century, the rise of cocooning was not enforced by censorship and authoritarianism. It was rather the other way around: de-politicization allowed for populism and neo-fascism.

At the same time, the private sphere has stopped being a discrete zone, and not just in how digitalization allows for everybody’s in-depth surveillance by states and corporations. With social media, people started broadcasting their private matters to the world. Already in the 1970s, sociologist Richard Sennett observed “the tyrannies of intimacy,” or how socio-political liberalization and economical welfare stirred narcissistic self-expression and undermined the traditional public sphere of impersonal relations. Hippies showered strangers with love, and politicians were elected for their personal traits. People insisted on being addressed not in a general manner but with respect to personal sensitivities. A discourse about trigger warnings and micro-aggressions took shape.

More abstractly speaking: the era of the citizen was about to be replaced by that of the individual. This implied an overall change of society that went beyond tearing down or re-erecting walls between the public and the private or one of the two disappearing. What happened was a remodeling of the private and public spheres. To understand this properly, we have to review the basic concepts and interplays of home and territory:

A) Animals might claim a territory for exploitation or, alternatively, a home for shelter. The territory preexists and caters metabolic supplies; the home serves procreation and recreation and might be to some extent self-created. Some animals also cater metabolic supplies within their home through the division of labor and symbiosis with other animals or plants.

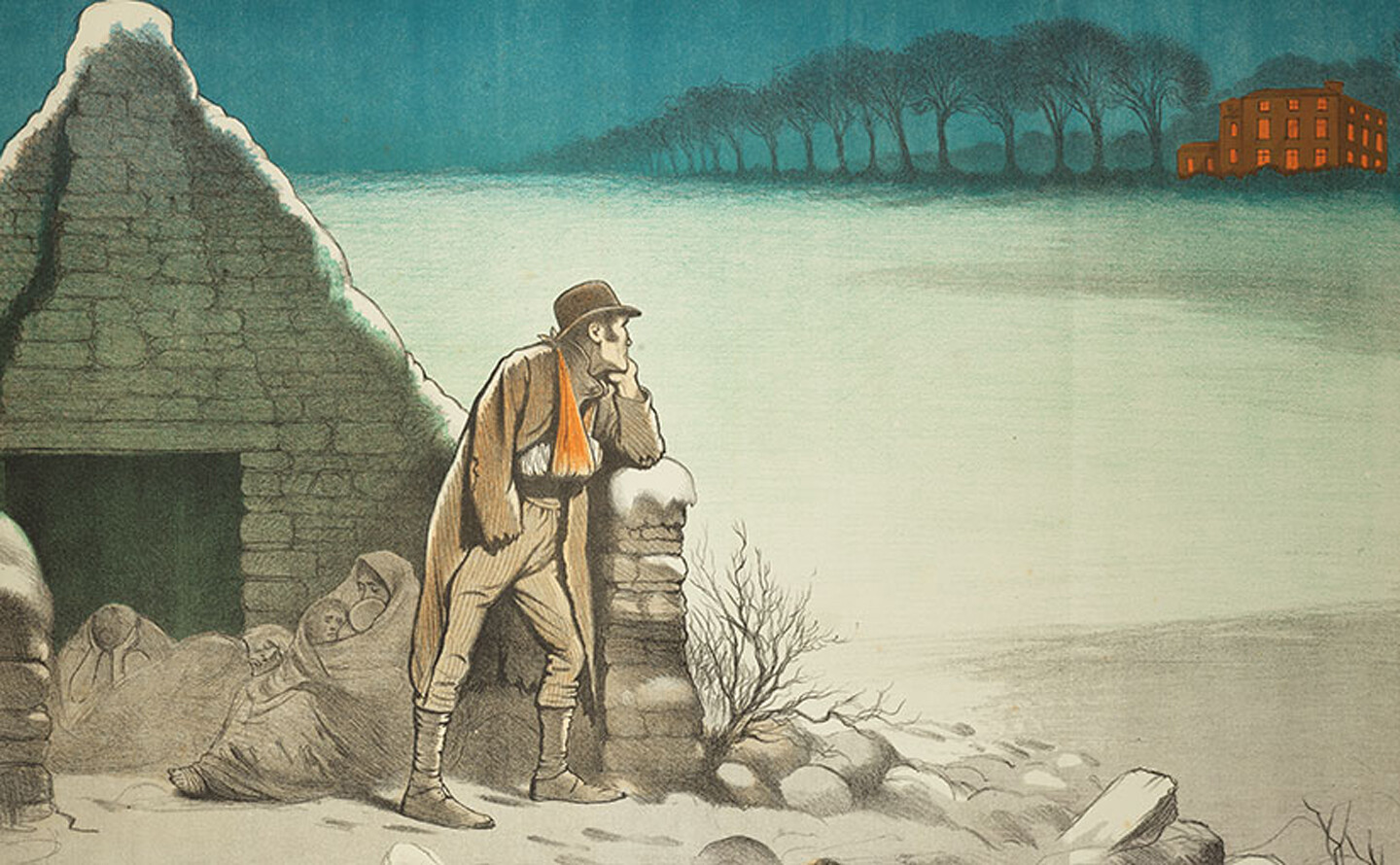

B) Due to the advanced use of tools like weapons, fire, clothing, and paint, human hunter-gatherers claim both a territory and a home. The domestication of plants, other animals, and themselves as serfs—the breeding and training of organic robots—allows for the introduction of agriculture. Peasants do both: they expand the functionality of the territory to the home (husbandry, craftsmanship) and the protectiveness of the home to the territory (fences, weapons).

C) Through the specialization of tools and skills, the division of labor expands beyond a single herd or family. As citizens, humans share a common—public—space with all other citizens to exchange between their territories and homes. This exchange is overseen by a state that is in charge of law and money.

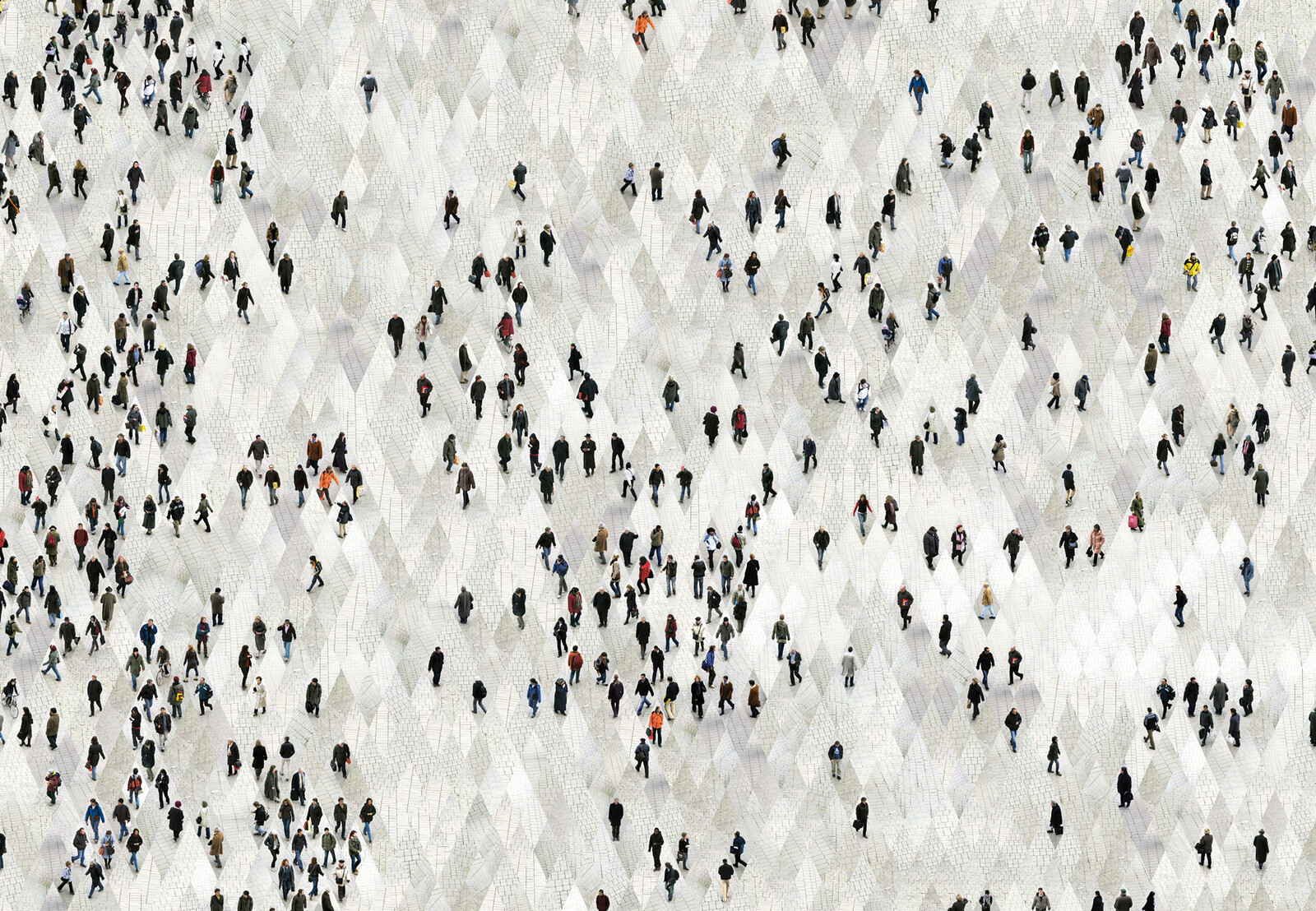

D) With advanced mechanization penetrating all aspects of life, the division of labor not only applies to movable goods. Humans divide their own lives between different temporary or partial homes and territories that they share with alternating others. The congestion of cities allows for a maximal fragmentation of life. Urbanites live next to and with strangers (apartment complex, hotel, flat share), eat next to and with strangers (restaurant, cafeteria), party next to and with strangers (bar, club), have sex next to and with strangers (darkroom, brothel, hook-up), recreate next to and with strangers (park, beach, spa, resort), and move next to and with strangers (trains, planes, public transport, taxi). To overcome the instinctive drive for a safety zone toward strangers, what zoologist Heini Hediger named “flight distance,” urbanites try not to or at least pretend not to notice the others. They treat them as vectorial obstacles, evasive liquid, or as particles of a greater body to unite with.

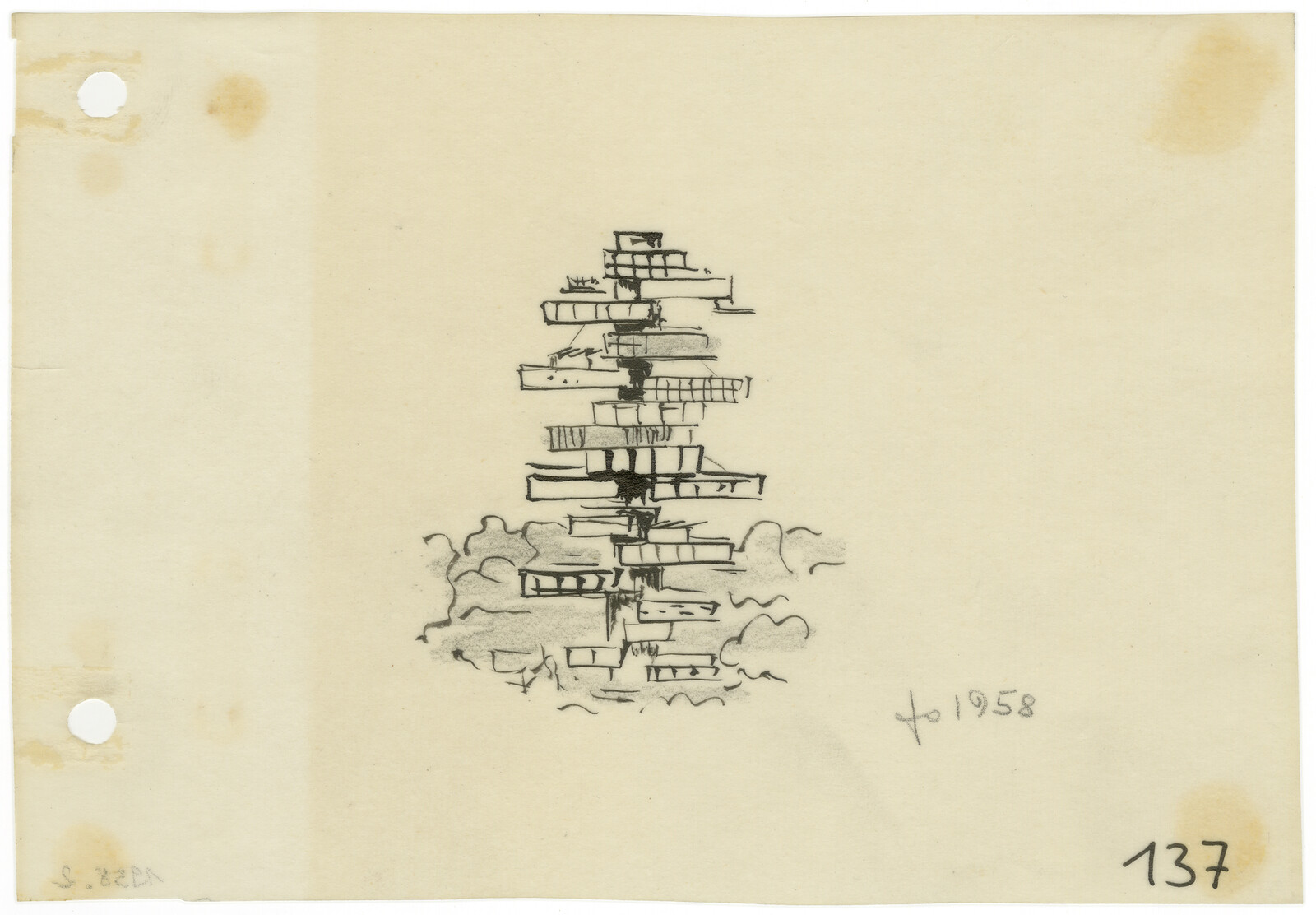

E) Digitalization allows for machines to operate automatically, to shrink in size, to be easily reprogrammed, and then even easily remodeled. Humans reduce their labor and its division, and become individuals. To understand what that means, we can project where the Covid-19 pandemic is taking us: we might live as congested urbanites, but we avoid random encounters. Robots cater, transport, maintain, and satisfy, and communication and entertainment are virtual. However small, our home can be an office, a factory, a farm, a school, a hospital, or a prison. Even when we enter the street in person, we don’t have to meet anybody. We don’t even have to pay attention to the actual street: through a warning system, similar to a parking system, we keep enough distance not to bump into each other or transmit a disease. Through a protection system, we fend off unwanted weather, noise, and pollution. Rather than sharing home and territory we take them with us, or at least create them virtually wherever we are. The parameters of our home and territory don’t change unless we want them to. We are in our own shell even when entering that of somebody else—unless we both approve to unite for a certain period of time. This can happen gradually. There’s an endless range of degrees of convergence between singular and group isolation. Whenever we agree to an intimate encounter—of a physical kind or even just mere communication—all members of our social groups as well as their social groups get notified. Depending on their safety parameters, they might shut us off permanently or just for testing.

As citizens, we follow general guidelines—ranging from universal natural rights to local manners—within which we are allowed to act freely. As individuals, we renegotiate and recalibrate our code of behavior before, during, and after every encounter. Just as explicit violence, the implicit violence of random encounters becomes a matter of choice. On an urban or global scale, this boundless contingency is only maneuverable with computational support. Like farms and cities, states don’t disappear. But for individuals, they become just another cluster within an immense agglomeration of mutual agreements. Citizenship is gaining the character of a membership or a share rather than that of a birth-sign; it’s neither written in stone nor in our genes. From this perspective, “classical” Western democracies are authoritarian systems: their constitutional cores are not meant to be changed.

Another problem with them is their reliance on strict majority rule and the dichotomy it creates between ruling parties and their opposition. Individuals understand themselves as so diverse that a majoritarian rule can only be about what’s in the interest of a majority, not what’s right or wrong for all. This is even more the case as individuals put any eternal law into question—even when it protects minorities and delinquents. Therefore, governments have to ensure wide consent. This can happen either by consociationalism (as in Switzerland, which isn’t led by a president or prime minister but by a federal council that represents almost the entire political spectrum) or by the segregation into more homogenized, populistically ruled states. A combination of both is also possible: more homogenized, largely autonomous sub-states governed under the umbrella of a federal council. Substates don’t require territorial integrity. Zones of territorial exclusivity can be splattered and temporary—depending on the movements and agreements of their current citizens.

Today’s prevalent technological concepts haven’t fully caught up with an individualizing society. While our communication devices are all about connecting and sharing, we tend to fall back on old-fashioned concepts like walling-off or locking down the physical sphere. We isolate ourselves, yet don’t gain any privacy—just the opposite. To fear no harm, we allow our personal data to be mined and make ourselves as predictable as possible. The more we feel observed, the more we become reserved. Openness and social anxiety go hand in hand. We lose our privacy and are lonelier than ever.

The next trillion-dollar enterprise won’t be about connecting, but keeping one’s distance. While social media allows us to get in contact wherever we are without any effort, this endeavor allows us to be by ourselves wherever we are without any effort. Our very own bubble will be protected from observation or interference from people and entities that are not explicitly invited. To all the others we will become a black box. We won’t be seen or heard.

This “automatic” privacy can also be applied to keep humans away from certain animals, in particular during sensitive periods like mating or egg hatching, or to keep predators and their prey at a distance. Both receive signals to shy away from each other: the predators are lured to artificial prey and the prey to birth control.

The earth could become a place where Jainism is not just a personal practice but a general disposition. At worst, two virtual bubbles bounce against each other and drift apart. Over time, this system can become more and more sensitive and include more and more species. An advanced system able to deal with traffic, housing, and vegetation could navigate human and nonhuman interaction on the whole planet.

Housing is a collaboration between e-flux architecture and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Chair for Theory of Architecture.