A 2016 report in Nature Climate Change states that climate change will make much of the Arabian Peninsula too hot for humans, pushing past limits of adaptability by the end of the twenty-first century.1 Not only will air conditioners run at increasing rates, but residents of the region will also suffer from freshwater scarcity.2 If they remain oil-rich, states like Saudi Arabia will manage to supply the necessary electricity to keep indoors temperatures cool, but outdoor activities will become nearly impossible in such intense heat and humidity.3 Conversely, if oil runs out or loses its value, these countries might no longer be able to afford such infrastructural solutions, resulting in what the report bleakly describes as “premature death of the weakest—namely elderly and children.”4 As the report concludes, “A plausible analogy of future climate for many locations in Southwest Asia is the current climate of the desert of Northern Afar on the African side of the Red Sea, a region with no permanent human settlements owing to its extreme climate.”

As such dire climate change predictions circulate, so do announcements about mega and giga projects that seek to offer inexhaustible energy and desalinated water.5 In 2017, Saudi Arabia’s Mohammed Bin Salman announced NEOM, envisioning a master-planned region spanning 26,500 square kilometers—an area comparable in size to the state of Massachusetts—that would straddle Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan and Israel. Situated in the Tabuk district in northwestern Saudi Arabia, the free trade zone will contain three separate cities housing nine million people by 2045: Trojena, Oxagon, and the much-advertised The Line. With a compound name that merges Greek word “neo,” meaning “new,” and the Arabic word “mustaqbal,” meaning “future,” NEOM supports the Saudi Vision 2030, which lays out the country’s aspirations for reducing its dependence on oil exports and developing new sectors for generating wealth.6 In a context of uncertainty about the political, economic, and environmental future of the Arabian Peninsula, marketing and promotional material for NEOM plays a vital role, demonstrating that Saudi Arabia will diversify its economy away from fossil fuels and overcome possible ecological, social, and financial crises with the help of new design solutions, business models, and technological innovations. In doing so, it helps secure future legitimacy for the country’s rulers, promising progress and stability.

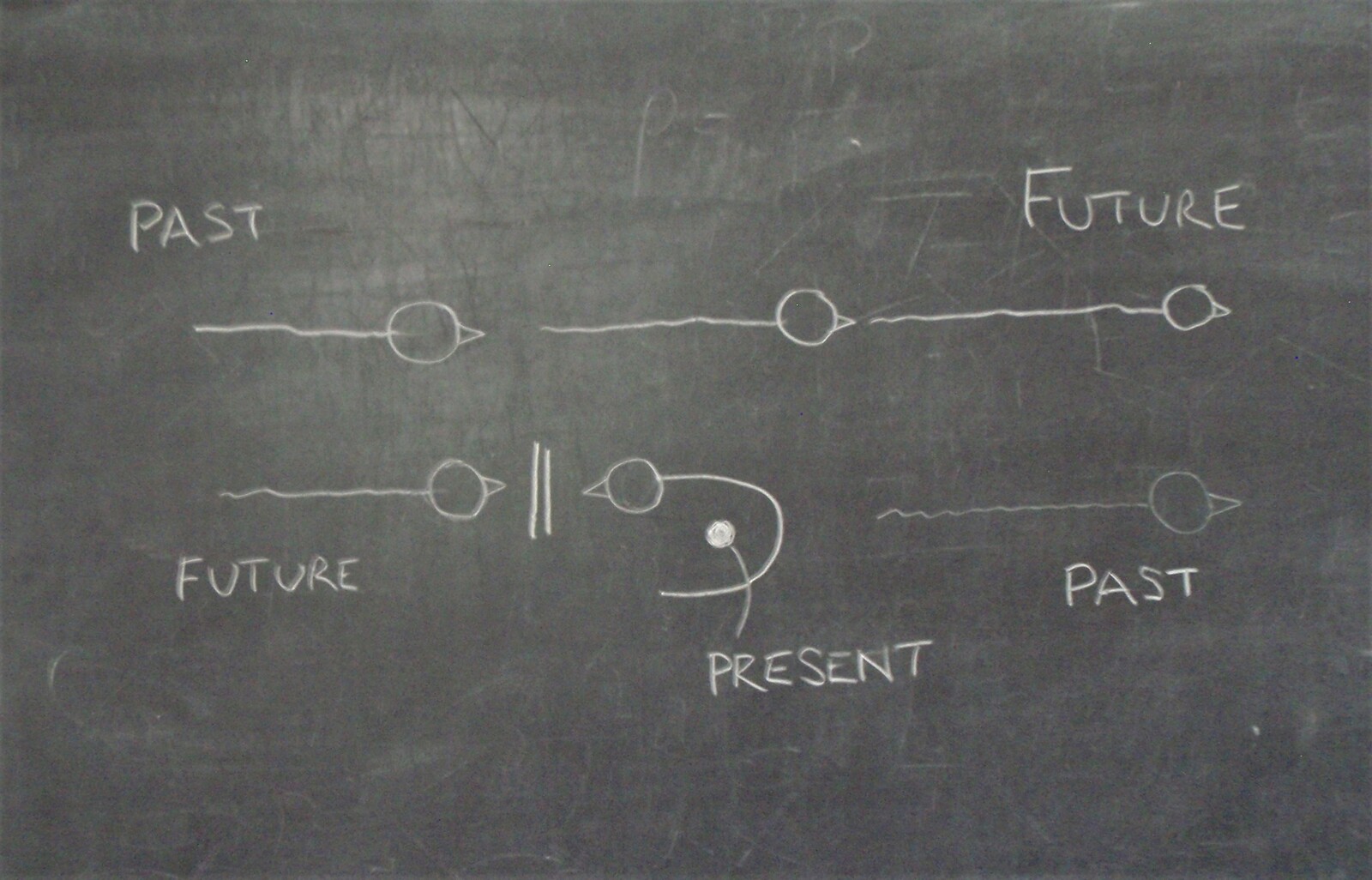

In financing NEOM, oil-rich Saudi Arabia has no choice but to extract and export more fossil fuels for an eager global market, prolonging the harmful effects of carbon emissions. As literary critic Stephanie LeMenager contends, the “petrotopia” will “repress the violence it has performed,” in an effort to conserve its present form.7 Inside NEOM, the benefits of twenty-first-century living will be perfected through what Saudi Arabia’s rulers have called “a civilizational revolution.”8 As Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman outlined in his launch announcement for The Line in January 2021, outside such spaces, time will inevitably move towards catastrophe. “By 2050, one billion people will be displaced due to rising CO2 emissions and sea levels,” Mohammed bin Salman exemplified.9 NEOM’s cities seek to remain isolated from what happens outside, both spatially and temporally. It is perhaps no surprise then that The Line is essentially a monumental wall.

Yet according to NEOM’s advertising material, The Line is much more than a wall. Its promotional videos describe the future city as a space “that delivers new wonders for the world.” Originating from a work by Philo of Byzantium written in 225 BC called On the Seven Wonders, and made known by the late Roman writers Martial and Cassiodorus, the “Seven Wonders of the Ancient World” were the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Colossus of Rhodes, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, the Temple of Artemis, the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, and the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.10 Of these seven, the Great Pyramid of Giza is the only one that survives today. In parallel with The Line, these ancient artifacts of the Mediterranean world enliven contemporary imaginations through their many renditions. Yet many of them do not materially exist, and therefore indefinitely remain inaccessible to human experience. As historians of science Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park remark, “wonders… registered the line between the known and the unknown,” determining the limits of possibility.11 By positioning The Line as a project that will create new wonders, developers employ such mythical histories as an endorsement of their work in Saudi Arabia, projecting monumental grandeur onto an abstract future and disseminating these visions within a present in which they cannot be held fully accountable for their projections. The Line’s ambitions lie in the interstitial space between the known and the unknown.

Philips Galle (after Maarten van Heemskerck), “Kolos van Rhodos” (1572). Source: Rijksmuseum.

While the slogan “new wonders for the world,” may provide the mythical bedrock for The Line, it also references the birth of new generations of humans inside the city, constituting such ordinary new wonders in themselves. In one marketing video which covers Louis Armstrong’s 1967 single “What a Wonderful World” as its soundtrack, a young woman, seemingly bored of her gray, congested life in a metropolitan city, crosses through a silver pinwheel-shaped gate only to find herself floating through the lush and pristine spaces of The Line.12 The young woman has now become an Alice in Wonderland, defying gravity. As she lands on a rooftop, a group of children are attending a class in the background, evidence of cultivated future generations sprouting in The Line. A boy playing with a robot figurine in his family’s living room notices her as she flies by their apartment’s windows. The video instructs its viewers that while some of the pioneers that NEOM seeks to attract will move there from metropolitan cities (and perhaps become airborne with the intensity of this new experience), others will be raised inside the Line. In abiding by the city’s technocratic norms, future generations will themselves emerge as wonders.

NEOM’s marketing material not only temporalizes its ambitions by drawing on elusive histories and reproductive futures. It also frames the Tabuk region as an empty, unexplored terrain where innovative modes of living will emerge with the arrival of NEOM’s new population. A promotional video broadcast in October 2017 foregrounds the region’s boundless potential: “You can look at these ancient hills and see nothing. Or you can see nothing to hold you back. No set ways of thinking, no restrictions, no divisions, no excuses. Just endless potential. This is the blank page you need to write humanity’s new chapter.”13 Many colonialist and settler colonialist projects have regarded arid lands as blank or ruined spaces, which can be fixed with the help of technology and proper governance.14 As geographer Diana K. Davis shows, European colonizers conceptualized the desert as a geography that has been generated due to misuse by its native peoples, and therefore needs to be improved.15 For colonizers, the desert was terra nullius, an uncultivated frontier, open for experimentation by settlers of all kinds.16 As one NEOM marketing video from September 2021 announces: “You see the desert. We see opportunity.”17

In a 2007 essay on urban development in the Gulf, Rem Koolhaas echoes this vision. “We live in an era of completions, not new beginnings. The world is running out of places where it can start over,” he writes. “Sand and sea along the Gulf, like an untainted canvas, provides the ultimate tabula rasa on which new identities can be inscribed: palms, world maps, cultural capitals, financial centers, sport cities…” Koolhaas situates the Gulf as a region that had yet to be been discovered, and therefore has the potential to serve as the destination for novel ambitions; where the world can “start over.”18 According to these perspectives, the arid territories of the Gulf are the ultimate “empty space” upon which novel ideas can be imposed. And yet, by perceiving these territories as a frontier for capital accumulation, the developers of real estate projects have in fact exacerbated the very ruin the early generations of colonizers projected onto such arid landscapes.

The premise of such experimental and insulated real estate projects is not new to Saudi Arabia, even though the infrastructures of insulation may have changed over the past decades. In fact, as political scientist Robert Vitalis lays out, segregationist urban forms that were products of the Jim Crow era United States were exported to the Arabian Peninsula in the 1950s through the founding of oil-towns, the most iconic being Aramco’s Dhahran in Saudi Arabia.19 Test-beds for perfecting segregation, these company towns relied on the assumption that people from diverse backgrounds could not cohabit cities, and offered separate living quarters for workers with different ethnic, racial, and educational characteristics. Amenities such as air conditioning were only available to American executives, for instance, and blue-collar workers could not freely move around the compounds. In preparing for a post-oil future, projects such as NEOM follow this genealogy, but replace oil with alternative industries such as artificial intelligence technologies, robotics, and machine learning. In the same way oil company towns formed the basis of the fossil fuel industry, NEOM seeks to facilitate the emergence of a Silicon Valley future, what one marketing video for Oxagon calls “a cognitive city.”20

NEOM’s future centers on automation. As such, it promotes the emergence of smart cities populated by humanoids. Its marketing efforts foreground how robots will outnumber humans in the city, automating every form of labor possible and enabling surveillance and cyber security. A report from 2019 suggests that NEOM “should be an automated city where [the decision-makers] can watch everything, where a computer can notify crimes without having to report them or where all citizens can be tracked.”21 In collaboration with Chinese technology company Huawei, Saudi Arabia has launched the National Artificial Intelligence Capability Development Program which will service these broader goals. Israeli NSO group, known for its spyware Pegasus, also participates in the construction of NEOM’s digital infrastructure.22 As an enclave that will not be governed by the Saudi government, but rather managed by a chief executive officer, the city promises to produce a seamless, flexible, technocratic space, ideal for drone deliveries and driverless transport, where all citizens can be tracked effortlessly.

In this projection of a robot-run future, some humans may constitute a nuisance. Members of the Huwaitat tribe, inhabitants of the area that now constitutes NEOM, have already been evicted to make space for future robot populations. News reports show how those who have protested evictions have been shot and killed by Saudi State Security.23 But it is not only the indigenous Bedouin populations of the area that are undesirable. According to NEOM’s marketing material, the working-class immigrant labor force who over the last decades has built real estate developments and infrastructure projects throughout the region will not be providing services inside these new cities. Instead, renderings for Oxagon, the industrial heart of NEOM, depict fully automated factories and ports, operated by an international group of people that NEOM’s advertising calls “pioneers.”24 And in taking the initial steps to achieve the goal of replacing workers with robots, Saudi Arabia granted citizenship to a humanoid called Sophia as she addressed the audience at the Future Investment Initiative in Riyadh in October 2017, the launch event for NEOM. The countries of the Arabian Peninsula are known for their strict immigration policies, which make permanent residency and naturalization very difficult if not impossible for immigrant humans, rendering the act of extending citizenship to Sophia especially poignant.25

While discussions on automation and surveillance are prevalent globally, both as something to be feared and as something to be desired, not every automation project has shared this divisive view of social life. Scholars have criticized the ways in which automation may result in worker deskilling and the centralization of decision-making on factory floors, especially underlining how it reinforces hierarchical organizational forms.26 Others, however, have argued that automation can lead to the distribution of decision-making across the work floor, generating more egalitarian power relations between employers and employees. As historian of science Eden Medina explains, Stafford Beer, a cybernetician involved in Project Cybersyn in Chile in the early 1970s, had imagined his efforts to “change how management decisions were made, whose knowledge was used to make these decisions, and how workers, technologists, and managers interacted.”27 According to this perspective, educating workers about automation systems and involving them in decision-making would not only improve the computer system, but also increase productivity.28 In light of such debates, the Saudi model of replacing workers with a carefully engineered humanoid population points to a specific aspiration for total control, where the yearned for robots are expected to be epiphenomenal to existing social relations—a conclusion that the literature on automation would reject. Regardless, as it is supported by global corporations and expertise, NEOM now provides a testing ground for experimenting with this particular technocratic longing for total control.

When recruiting white collar workers for NEOM, job descriptions sometimes include references to the science fiction classic Blade Runner (1982), and commentaries with titles such as “Blade Runner in the Gulf” abound.29 Blade Runner is set in Los Angeles in 2019, a sprawling global metropolis. Its narrative centers on a group of synthetic humans, which have been bioengineered by the Tyrell Corporation to work in outer space colonies, who manage to find their ways back to earth. Deckard, a blade runner who specializes in eliminating these replicants, is given the responsibility to track them down. While sketching novel forms of transportation and urban planning, Blade Runner is a dark critique of authoritarian environments, characterized by irreversible ecological degradation, absolute corporate control, and unrestrained police violence. Yet regardless of the film’s dystopian nature, urban projects in the Gulf, such as NEOM, remain associated with Blade Runner both by the developers of these projects and by their critics.

Superstudio, Il Monumento Continuo, Positano (1969). © Centre Pompidou, Mnam-CCI.

The irony is not only that Blade Runner is nightmarish, but also that it is nearly half a century old, indicating an imagination of a future that has itself become historical.30 In its imagery, NEOM draws on and reproduces a retro-future dating back as far as the 1960s. For instance, a critical inspiration for NEOM’s 200-meter-wide, 500-meter-high, and 170-kilometer-long city The Line is the Italian architecture office Superstudio, a pioneer in the radical architecture and design movement of the late 1960s. The Continuous Monument, which today forms the basis of The Line, was first shown in Graz in 1969 as a critique of modernist urban planning. At the time, members of Superstudio conceived The Continuous Monument as an unbuildable project that critically amplifies the sharp divisions between the built environment and its exteriors. The Line, however, positions such sharp divisions as an asset: “The Line is designed as a series of unique communities, providing equitable views and immediate access to the surrounding nature.”31 The mirrored glass façade of The Line not only cuts through the landscape but also repels the environment outside, highlighting how the massive building is context-free and placeless. Even though the city is insular and self-contained, human and nonhuman outsiders who may happen to pass by and attempt to peek in will not encounter any outer walls. Instead, they will see their own reflections, embedded in the yellow of the environment that surrounds this continuous monument. In a 2021 interview which touches upon The Line, the Superstudio member Gian Piero Frassinelli remarked to The New York Times: “seeing the dystopias of your own imagination being created is not the best thing you could wish for.”32 The imagery for Superstudio’s The Continuous Monument might appear identical to The Line, but the historical and political contexts in which the two projects circulate endow them with contradictory meanings, generating competing claims about the correct readings of such monumental forms.

By situating NEOM in such retro-futures, the developers of these projects allude to the aborted promises of modernity. In the twenty-first century, carbon-based imaginaries of the future that laid the foundations of mid-twentieth century modernisms and drew on the assumption of infinite oil are perhaps foreclosed. But NEOM positions its audience back in the mid-twentieth century, claiming that the expectations of progress that belong to this former era are still available in Saudi Arabia despite their apparent disappearance from the global North. Perhaps this is one reason why NEOM attracts so much attention in international media, producing a kind of nostalgia for a bygone time. Yet in doing so, NEOM helps generate a specific modality of governance, one which will protect the collective from existential threats such as energy shortages, water scarcity, and climate change. In subscribing to these ideals of progress, however, humans will have to mimic automatons, closely following the mandates of the technocracy in which they are encapsulated.

In a post-oil future, life in the Arabian Peninsula may be characterized by temperatures beyond human habitability. Absence of groundwater sources will generate a climate that the inhabitants of the region have not experienced before. Yet NEOM’s marketing and promotional material seeks to demonstrate that the inhabitants of these enclaves will not have to confront the consequences of the fossil fuel economy, enjoying nothing but its potential. Despite mounting environmental pressures, NEOM’s advertising offers the promise of stability against the disruptive consequences of climate change in a highly securitized test-bed.

Jeremy S. Pal & Elfatih A. B. Eltahir, “Future temperature in southwest Asia projected to exceed a threshold for human adaptability,” Nature Climate Change 6 (2016): 197–200.

Gökçe Günel, “The Infinity of Water: Climate Change Adaptation in the Arabian Peninsula,” Public Culture 28, no. 2 (2016): 291–315, ➝.

Air conditioners consume about 70% of the electricity produced in the GCC. For an analysis, see Gökçe Günel, “The Backbone: Construction of a Regional Electricity Grid in the Arabian Peninsula,” Engineering Studies 10, no. 2–3 (2018): 90–114, ➝.

Pal and Eltahir, 199.

My book Spaceship in the Desert (Duke University Press, 2019) investigates the temporal and spatial characteristics of Masdar City in Abu Dhabi, another significant project in the Arabian Peninsula. There are many conceptual similarities between Masdar City and NEOM, and the analysis in this piece parallels some of my work on Masdar City. Yet the projects embody different scales. For instance, Peter Terium who leads the Energy, Water and Food sector of NEOM, told me on a NewCities Foundation panel in August 2021 where we were both panelists that NEOM “is not a spaceship” and that “it is a region.” Yet both Masdar City and NEOM aspire for technocratic transformations that take their references from the 1960s, and project new kinds of potential onto arid landscapes. I discuss the conceptual similarities and differences of these two developments and trace their genealogies in a forthcoming article: “The Future of Temporality in the Arabian Peninsula.” In: Chad Elias eds., Futures Uncertain (Duke University Press, forthcoming).

First publicized in April 2016, Saudi Vision 2030 draws on a McKinsey report from December 2015, titled “Saudi Arabia Beyond Oil: The Investment and Productivity Transformation,” ➝.

Stephanie LeMenager. “The Aesthetics of Petroleum, after Oil!” American Literary History 24, no. 1 (2012): 59–86.

“HRH Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman announces designs for THE LINE, the city of the future in NEOM,” ➝.

NEOM, “Launch Announcement of The Line,” YouTube, January 10, 2021, ➝.

See for instance: Paul Lunde “The Seven Wonders” Saudi Aramco Magazine (1980): 14–27, ➝.

Lorraine Daston and Katharine Park, Wonders and the Other of Nature: 1150-1750 (New York: Zone Books, 2001), 13.

NEOM, “NEOM | THE LINE - New Wonders for the World,” YouTube, July 25, 2022, ➝.

ArchDaily, “NEOM, The Futuristic Mega City Saudi Arabia Is Planning,” YouTube, October 26, 2017, ➝.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the English word “desert” is derived from the Latin word “desertum,” meaning “abandoned, deserted, left waste.” The Arabic Word for desert, “صحراء” refers to the color of the sand instead, and is etymologically linked to words red and yellow.

Diana K Davis, The Arid Lands: History, Power, Knowledge (MIT Press, 2010). Samia Henni’s 2022 edited volume Deserts Are Not Empty also explores this history (Columbia University Press, 2022).

For another example, see Emilio Distretti, “Titanic in the Desert,” Cabinet Magazine 63 (2017): 53–61.

NEOM, “This is NEOM,” YouTube, September 16, 2021, ➝.

Rem Koolhaas, “Last Chance?,” Al Manakh (Archis, 2007), 7.

Robert Vitalis, America’s Kingdom: Mythmaking on the Saudi Oil Frontier (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2007). For another analysis of segregationist urban forms, see Pascal Menoret, Joyriding in Riyadh: Oil, Urbanism, and Road Revolt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

NEOM, “What is OXAGON?,” YouTube, November 16, 2021, ➝.

Justin Scheck, Rory Jones, and Summer Said, “A Prince’s $500 Billion Desert Dream: Flying Cars, Robot Dinosaurs and a Giant Artificial Moon,” Wall Street Journal, July 25, 2019, ➝.

James Lynch, “Iron net: Digital repression in the Middle East and North Africa,” European Council on Foreign Relations, June 29, 2022, ➝.

See for instance: Frank Gardner, “Saudi tribe challenges crown prince’s plans for tech city,” BBC News, April 23, 2020, ➝.

NEOM, “NEOM Pioneers,” YouTube, December 6, 2019, ➝. Surprisingly one of the main features of the NEOM Pioneers video are a plane wreck and a shipwreck. For a brief explanation of why the plane wreck is there, please see: “Why is there a seaplane in the middle of the Saudi Arabian Desert,” Esquire Middle East, ➝. For an overview of the shipwreck, see: Seema, “What is Georgios G Shipwreck?,” Neom City Guide, March 15, 2022, ➝. Both of these wrecks are from 1960, and are being framed as tourist attractions. “GEORGIOS G. SHIPWRECK,” Desert Paths, ➝.

See Noora Lori. Offshore Citizens: Permanent Temporary Status in the Gulf (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Shoshana Zuboff, In the Age of the Smart Machine (New York: Basic Books, 1988). Also see Zuboff’s recent book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (Profile Books, London, 2018), where she reviews the contemporary practices of “informating” and profiting from big data. See also Jesse LeCavalier, The Rule of Logistics: Walmart and the Architecture of Fulfillment (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 176–178.

Eden Medina, Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende’s Chile. (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011), 160–161.

Ibid, 282.

Vivian Nereim, “MBS’s $500 Billion Desert Dream Just Keeps Getting Weirder,” Bloomberg, July 14, 2022, ➝.

Based on Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the film Blade Runner was released in 1982, three years before Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman was born.

NEOM, “NEOM | What is THE LINE?,” YouTube, July 25, 2022, ➝.

James Imam, “Architects Dreaming of a Future with No Buildings,” The New York Times, February 12, 2021, ➝.

Horizons is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam.