“Before” and “after”: no expressions can be more commonplace, yet none, when you come to think about it, can be more perplexing. Imagine you are standing in a queue. There are people standing ahead of you; they arrived before you did, and are that much closer to the future towards which we are all shuffling. Then there are people behind you; they arrived after, and are that much further away. The former came early; the latter came late. Perhaps, if we were to enlarge the scale of our metaphor, we could imagine generations queuing up like this. There are people of your generation, lined up in a row. Ahead, in serried ranks, lie the generations of your forebears. Behind lie generations to come, preparing to make their way. Not all of these people, of course, may still, or yet, be alive. But even those who have “passed,” as we say, continue to cast their shadows over their followers, just as those who have yet to be born will emerge in the shadows of our own generation. But here’s the puzzle. For we are just as likely to say, of ancestral generations, that they lived in times past, and of descendant generations, that they will be the denizens of times future. The generations ahead of us, whom we had followed, are now behind; those behind, who had followed us, are now ahead. Before and after, it seems, have switched places. What can account for this curious reversal of fortune?

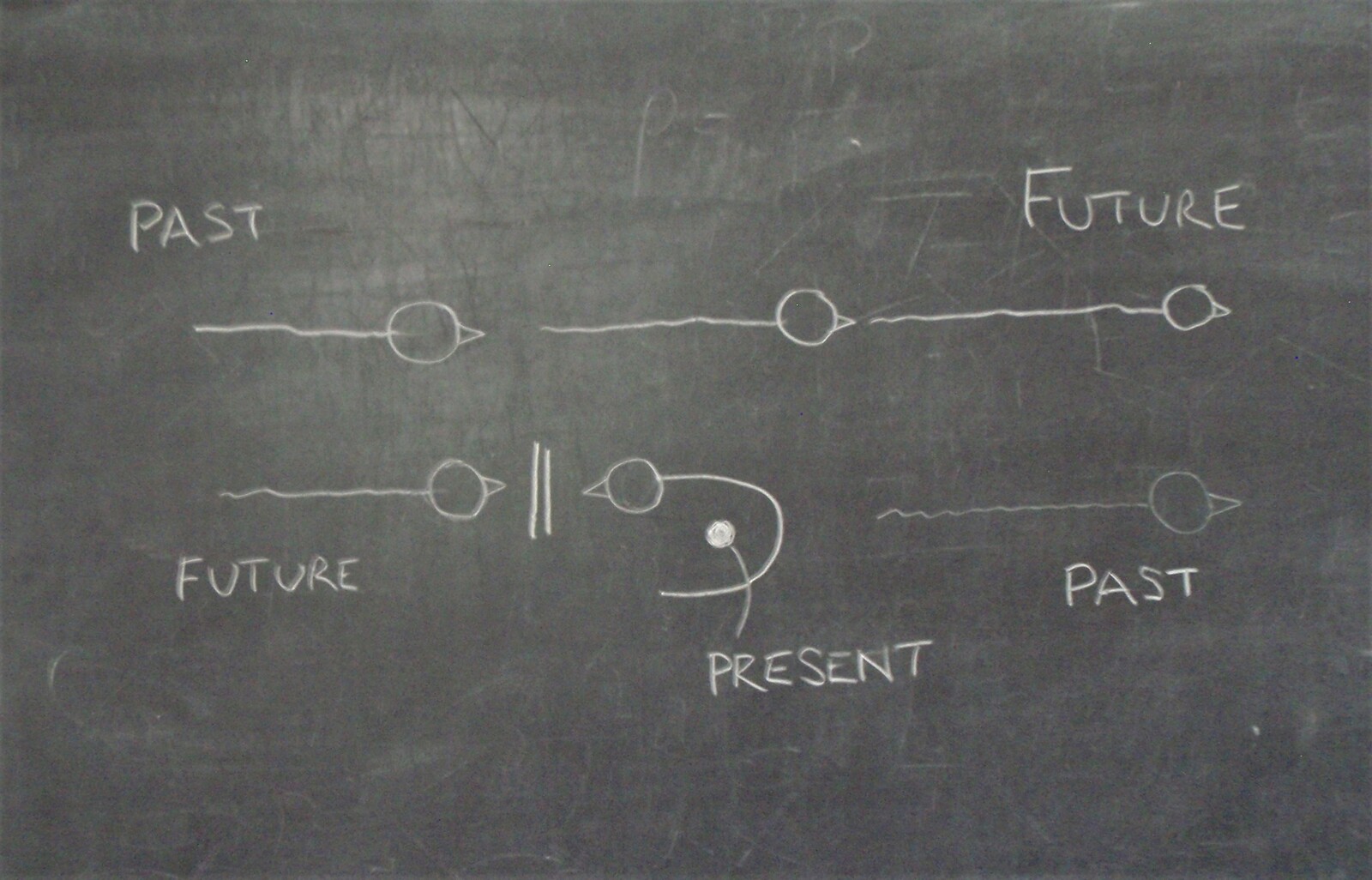

The answer seems to lie in a certain switch of perspective. The first perspective, which sees ancestors ahead and descendants behind, is taken from a position in the queue. Like everyone else, you are shuffling along through life, measuring out your days in steps towards a future which, like a spatial horizon, nevertheless recedes as fast as you approach it. But now suppose that you turn around, through 180 degrees. The people who once went before you are now at your back, while you now find yourself face-to-face with those who were once following after. The future, which had formerly stretched away into the distance, along ancestral paths, now appears to be heading, on a collision course, straight towards you. Meanwhile the ancestors, upon whom you have now turned your back, recede ever further into the past. Their time is over. The very act of turning, then, stakes a claim for the present. There is no present in the ever-moving queue, only the future’s past. The present is a hold-up, an attempt to arrest the passage of time. But no generation can hold its ground indefinitely. Eventually, the press becomes too great, and it is either pushed aside or forced to move on, to make way for the next generation that promptly does the same, turning its back on the one preceding only to face its own successor. The moment it turns, it takes the stand of a new present. History, then, reappears as a punctuated series of turning points, each a present moment.

To join the queue is to observe a tradition. The proper meaning of tradition is not to live in the past but to follow those who have gone before you into the future. You may be retracing old ways, but every tracing is an original movement to be followed in its turn. It is the same with storytelling, in which every tale picks up the threads of previous narrations and pulls them through, in a looping movement, into current life. Strictly speaking, then, to turn your back on tradition is not to relinquish what is already past. It is rather to deny the promise that tradition offers for the future. In other words, the “pastness” of tradition is not given a priori, but is produced in the very act of turning that stakes a claim to the present. This same turnaround, moreover, creates a future which, from the perspective of those still following traditional ways, is nothing if not backward-looking, sacrificing the possibility of ceaseless beginning for the finality of predetermined ends. We see this in education when the teacher, instead of inviting her students to follow in a gesture of companionship, turns to face them in a posture of instruction. We see it in architecture and design, which aspires not to resume the ever-unfinished work of predecessors but to cast the future as a project for the next generation to complete or discard. And we see it in a science that proceeds not by following the ways things are going but through cycles of conjecture and refutation.

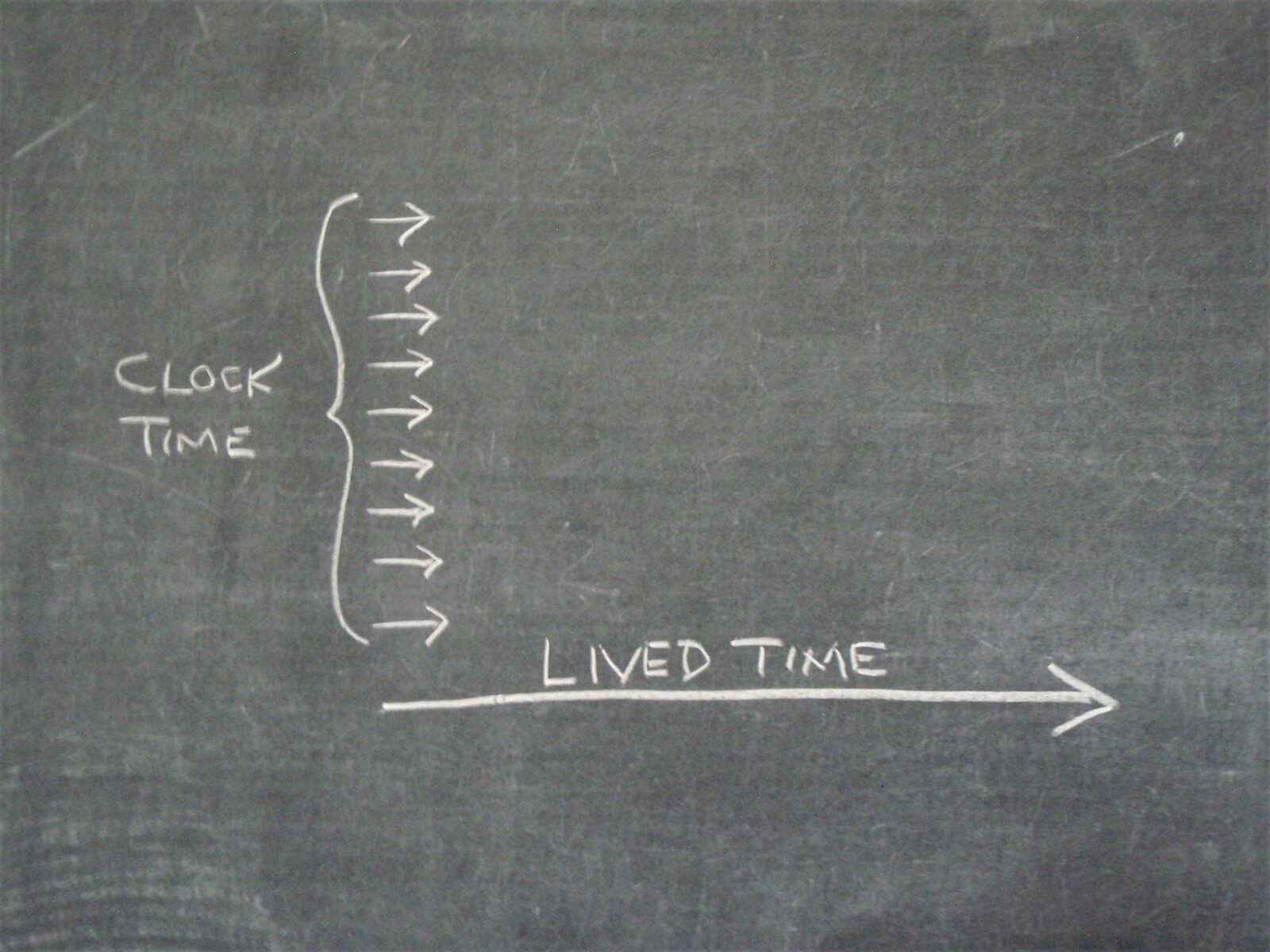

Such is the way of modernity. It is a way that measures time by the clock. Why, after all, does the clock tick? Its revolving movement, driven by the vital force of the spring, which wants always to unwind, or the weight of the pendulum as it gravitates to earth, is periodically stopped on the cog of an escapement wheel by a ratchet, only to be released again. The tick we hear is the sound of the ratchet’s engagement with the cog. And the measured time of the clock lies not in the unwinding of the spring but in the series of stoppages, each marked by a tick. So, likewise, do generations mark time by converting its onward movement into a punctuated series of escapements. With life as with time, the flow becomes a stutter. When life escapes, the entire series shifts by one notch. The foregoing generation, far from moving on into the future, vanishes into the oblivion of the past; while the generation to come, freed from the discipline of instruction, design, and conjecture to which it had once been subjected, pivots to take its place in the present, inflicting its own discipline on its successor. That’s why there is such a compulsion to replace the old with the new: it proves that time is passing and that history is being made. Nothing catches the modern imagination more than the idea of step change. Thus does every present generation, having turned its back to the past, take its place as a gatekeeper to the future.

This future, in the eyes of the present, figures less as a path to be followed than as a problem to be solved. Had it already been solved by preceding generations, now consigned to the past, there would be nothing for the present to do. They would have only to fall into line with a project mapped out for them in advance. Such compliance would amount to the renunciation of any future they could call their own. The present’s ownership of the future, therefore, depends on the assumption that the past got it wrong. This is the default assumption of the modern age: that the road from the past is paved with mistakes. We always know better than they did. Yet the inevitable implication is that our present solutions will, in due course, turn out to be equally misguided. And while the generation that proposes these solutions—that is, our generation—will pass, the effects of their imposition can linger, as have the impositions of generations preceding ours, leaving long-lasting scars not just on hearts and minds but on the world around us. Every generation, then, is fated to live among the ruins of outmoded futures. And although the predicament of coming generations will be no different, in principle, from ours, and ours no different from that of our predecessors, today’s present is perhaps without precedent in the sheer scale of ruination it is bound to confront. Never before have solutions for the future, inflicted by our immediate antecedents, wreaked such destruction on the conditions of earthly life.

Can there be any respite from the cataclysmic chain of ultimate solutions that generation after generation has inflicted on the planet, all in the name of progress? So long as we seek to shape a future perceived as coming towards us, by projecting our designs onto a world our successors are about to enter, the answer can only be no. We would be fated to the endless stuttering of the escapement mechanism. Stuttering, after all, is not a sign that progress is faltering; it is rather the way progress works, by serial replacement. Why else, along with the clock, are its iconic instruments the bulldozer and the crane? The bulldozer clears the ground of the traces of past interventions, leaving none to pick up and follow; the crane lifts new ones into place from above. If any traces remain of what has gone before, they are to be preserved as heritage. Preserving the footsteps of predecessors ensures, in effect, that we cannot ourselves walk in them. It is as though with every step, far from picking up ancestral trails and carrying them on, we roll out a new layer over the old, marked up with its own inscriptions. With each new layer, those already laid, if not obliterated, sink further into the past, never to come up again. That’s why the other side of progress theory is antiquarianism. A land of sedimented pasts can be excavated with impunity, since it can have no bearing upon a future for which it serves only as an inert substrate.

This is not, however, the only side-effect of the layer-by-layer theory of progress. Etymologically, the Latin verb generare, meaning “to beget,” has bequeathed the concepts not only of “generation” but also of “race.” But only since we have come to think of generations of humanity supplanting one another like layers in a stack, each of progressively superior stock, has the idea of race been freighted with the toxic connotations it has today. It was not always thus. Originally, race meant lineage, house, or kindred—people who could trace descent from a common ancestor, along a line of begetting and being begotten. Here, each generation issues from the one before, and into the one after, prolonging the former and anticipating the latter in a linear flow of vitality not unlike that of a running river from its headwaters to the sea. Like the river, the lineage flows downward. But generations, in their modern incarnation, stack upward, as each is slated to supplant it predecessor. Here, the life of each generation is expended in the present it has claimed as its own. No wonder the idea of indefinitely extending the life-span is so popular among those who consider themselves the smartest and most successful humans ever! Such an idea is only thinkable within a paradigm of human evolution that attributes advance to a ratchet mechanism which notches up superior variations while consigning the inferior to extinction. The concept of race, in its modern incarnation, is a specific pathology of this paradigm of human generational history, writ large.

Such a perverse conclusion is not inevitable. There is an alternative, which is to think differently about time and generations. It is to respect the wisdom of ancestors rather than working tirelessly to refute it. What if we were to cease pivoting on the present, and to look for guidance instead to those who have gone before? We and they would then be facing in the same direction, rather than back-to-back. In overlapping our lives with theirs, we could work together with them, not against them, to find a path forward. The alternative, in short, is to reclaim the way of tradition. Critically, this is not a recipe for conservatism. People who continue to follow their ancestors are not backward. All too often, the belief that they are stuck in the past, left behind by history, has been adduced to justify the colonization of their lands. It is a belief that comes, as we have seen, from putting tradition behind us. To join with tradition, facing frontward, promises otherwise, to open a future that, far from converging on any projected end, is indefinitely renewable. This is what it means to say of the future that it is sustainable. A sustainable world affords the possibility for life to carry on, forever. This is not to substitute long-term for short-term solutions. Only in the rearward view of a pivotal present can time appear as a nested series of scales. Genuine sustainability cannot be balanced on any scale, for every moment contains within itself the promise of eternity.

The progressive view of the present generation, as one that casts its projects retrospectively upon an imagined future, while relegating its forerunners to a discarded past, is easy to state but hard to dislodge. While in human history it is more the exception than the rule, it is so deeply embedded in the modern constitution that shifting it will require a wholesale reorientation of our approaches to education, design, and science. In education, the responsibility of the teacher would no longer be to articulate a new world, and to regulate students’ access to it, but rather to introduce them to an old world, allowing them to renew their lives in the very course of following its ways. This is not about the transmission of knowledge, from one generation to the next, but about the growth of wisdom in intergenerational collaboration. In design, it would mean a way of working best described as composition, by comparison with musical works. The designer-composer may be avant-garde, in the forefront, not however because their work is innovative, unlike anything that has gone before, but for precisely the opposite reason, because it is hyper-responsive to the voices of fellow creatures, and answers to their calls. In science, it would mean a procedure not of conjecture and refutation, as required by the logic of positivism, but of opening up to things, as they open to us, by joining with them and following their lead. Science, then would not educate us about the world; it would be the way the world has of educating us.

We cannot leap-frog our way into the future, or jump the queue. There is something illusory about the conceit that we can plan the future from the standpoint of the present, whether in terms of the educational curriculum, the designs of architecture, or the predictions of science. This is because the direction of projection is contrary to the flow of life. It amounts to a hold-up, which can only be broken by shelving the project and installing another in its place. Projection, in this regard, is the precise opposite of storytelling, in which the story and the life of which it tells are oriented in the same direction. To live the story is not to pivot on the present but, at every moment, to follow the thread of the future’s past. It means acknowledging that we are ever behind where we will be, and where others have already been. A sustainable future lies before us, if only we are prepared to keep our eyes on the way ahead, and learn from the lore of those who have gone before. We are like mariners on the high seas. The mariner knows fore from aft, bow from stern, and ploughs a course through the ocean guided by currents, winds, the sun and moon, stars and seabirds. What sensible mariner would place his aft in the future and his bow in the past? Yet this is what we do, whenever we project futures for ourselves. It’s no wonder, then, that we have lost our way.

Horizons is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam.