A “modern” man has nothing to add to modernism, if only because he has nothing to oppose it with.

—Elias Canetti (1989)

The tautological evidence of Canetti’s quote helps to sketch out a field of speculation on the conceptual liaison between modernism and modern heritage, the latter assuming the former as its essential condition. Historiographically speaking, a suggestive contact zone can be established between these concepts when questioning the significance of modern heritage vis à vis architectural history. At the present, the history of architecture is experiencing a strong wave of interdisciplinary regimes. In that respect, is the discipline, when confronted with the rising importance of the modern heritage, reassessing its cultural domain? Should the history of architecture be more inclusive, adding to its terrain a wider set of historical and historiographical approaches? Should scholarly practice be more analytical and allow a different approach to disciplines, formulating new objectives, and recipient of cross-pollination formulations?

In relation to heritage, memory plays a role within these exchanges. Nevertheless, memorization almost strangles our faculty of envisioning the future, even in terms of heritage, which is seen as only a token of the past. Paraphrasing David Lowenthal, whose works have been seminal in the field, I would insist on the fact that we live in an age of “memory overload.”1

The work of French historian Pierre Hadot (1922-2010), whose investigation into the development of what he defined as historia magistra, can help establish a common ground for a dialogue between disciplines that acknowledges a pluralism of well-rooted regimes of historicity.2 Hadot’s notion of time is an essential criterion for mapping out heritage. His dictum “le present seul est notre bonheur” (“the present alone is our happiness”), leads one to investigate the issue of the permanent present, or in other words, to look at history as continuum. A tool to legitimize a critical view on the question of temporality and heritage is grounded in the significance of the oxymoron “the present future.”

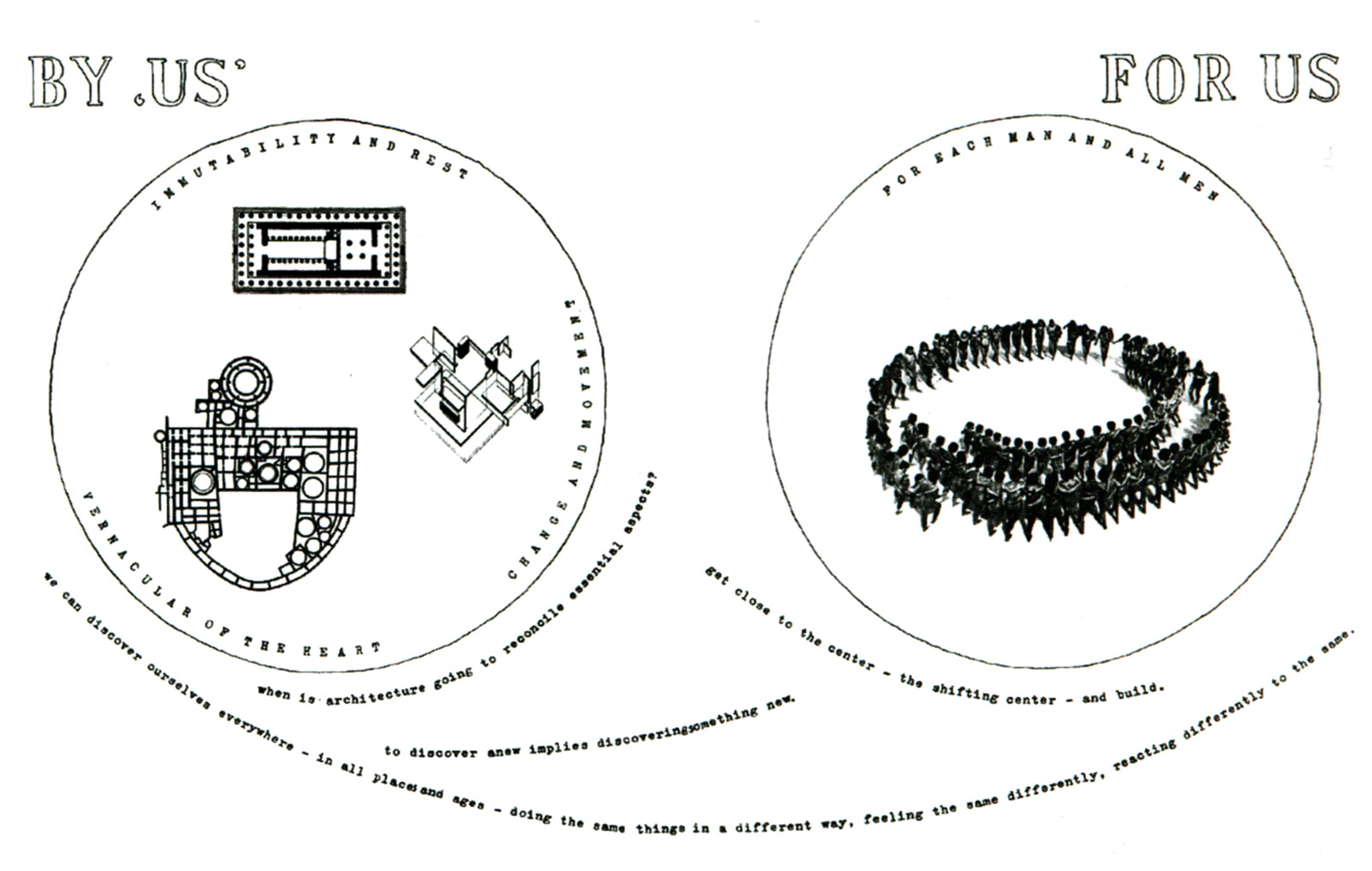

The fact that heritage and temporality are strongly intertwined has been extensively discussed and agreed upon by scholars in various disciplines. Heritage’s axiom is that it is not merely the gathering of significant artifacts that a society designates and in specific temporal conditions to become sign-bearers, but rather that it embodies the form of the relation that a society establishes with its own time. Heritage renders time’s order visible in the sense that it applies to the here and now of the object, to its current status.

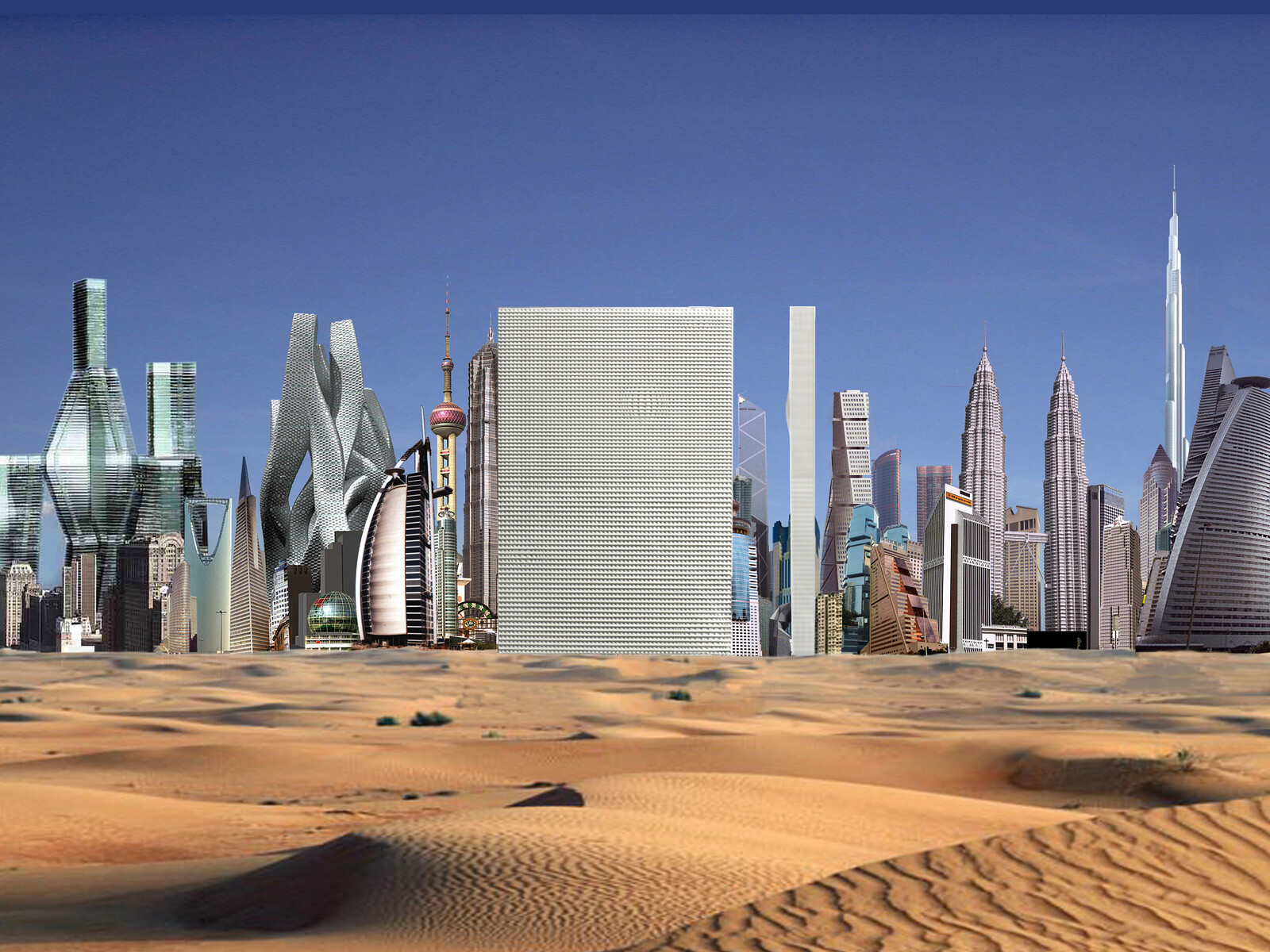

A methodological apparatus frames the exchange between history and heritage. This understanding is clearly remote from both the previous categorizations of the past as a model as well as the traditional received notions of heritage, and can allow for current forms of architectural production to be acknowledged and identified as our future heritage. Heritage can be observed from today’s point of view while also looking forward. Therefore, heritage is a modus operandi of and on the present, which is to say that it also molds and shapes our present.

Authenticity and Squandering

The concept of authenticity is identified as one of the dimensions of heritage, yet the notion of time modifies the cultural framework for questioning authenticity in modern architecture and opens it up in part to an anthropological discourse. Is authenticity also a criterion for attributing values to modern artifacts? In such a context, which expressions of authenticity are adequate as significant parameters in conservation practice? At which level is political negotiation a tool for conservation? Does persuasion through media and public awareness open a new perspective in the reception of modern heritage and in its historicization?

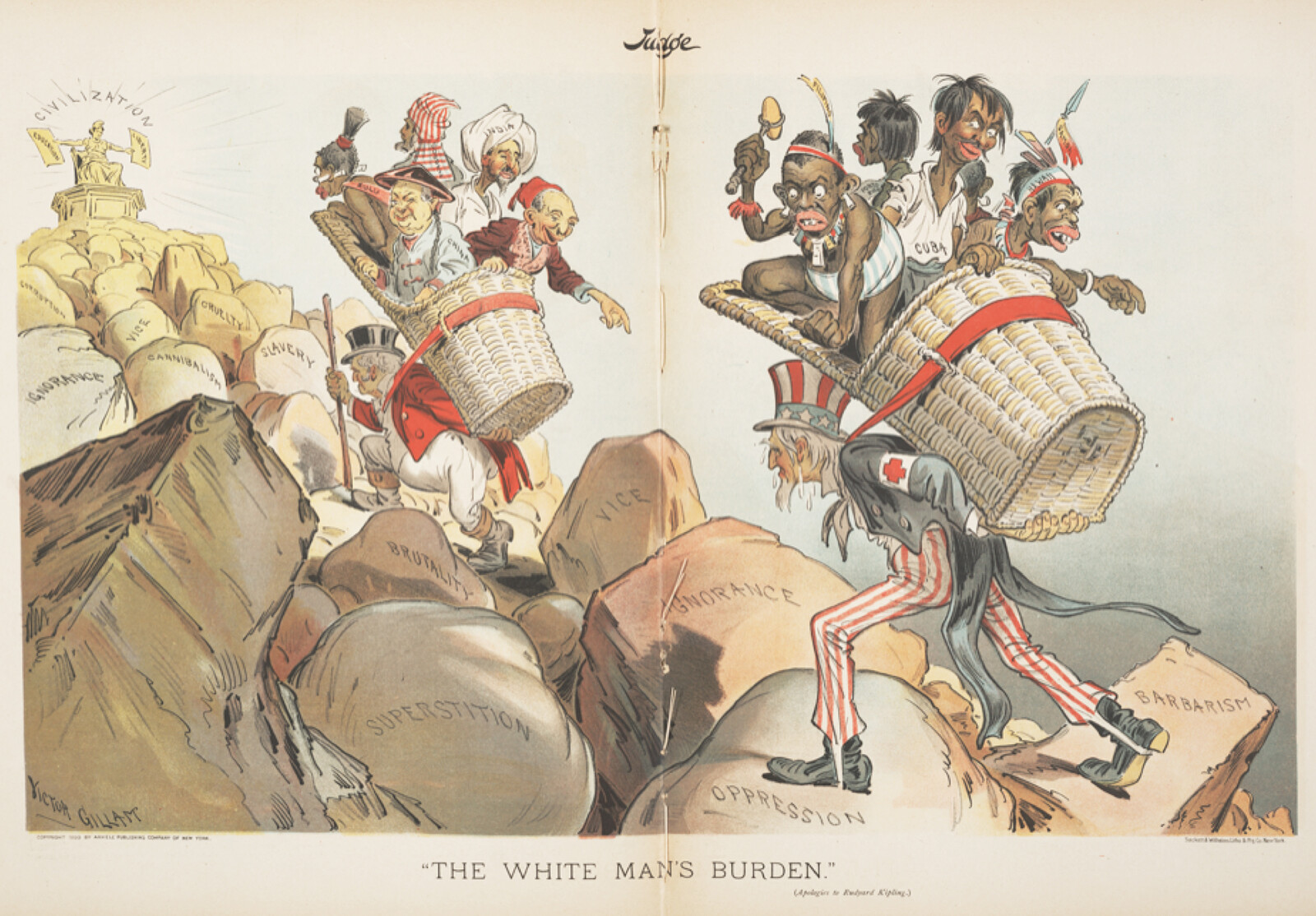

When critical regionalism entered discourse in the early 1980s, the search for identity and authenticity was seen as an archetypal paradigm in the cultural evolution of post-colonial societies.3 The question raised was: In order to get on with modernization, is it necessary to jettison the old cultural past that was formerly the raison d’être of a nation? Here the authenticity of the built artifact seems to be an appropriate criterion to forge a national spirit as well as to reinforce an identity in opposition to the colonial personality.

In our present age, we should take the need for an “ethics of authenticity” under consideration, which I refer to something specific and differing vastly from the traditional search for identical material properties. Authenticity refers to something creative, an authorship, something having a profound identity, but it also carries another concept, which is close and takes into account the historical continuity in the life of the heritage resource, identified by Alois Riegl as “age value.”4

The Nara Statement, the seminal document on authenticity from the Nara Conference, the sixteenth meeting of the World Heritage Committee in 1994, was inspired by the Venice Charter from 1964 on Restoration, and meant to locate authenticity at the apex of the concept of conservation, with the analysis of documentary sources and the increasing professionalization of protection and restoration at its base.

In order to understand the role of heritage within our contemporary society of happenings and communication, we may recall the strategy of reception developed by Umberto Eco in his concept of opera aperta, which may well be suitable to address the rising awareness of heritage in today’s society and also related to the question of authenticity.5 Eco refers to the two components of the work of art: the creative process and authorship, and the plurality of spectators, whose appreciation depends on different time conditions and on cultural and social characteristics. If this is the case, the truth of an artifact, and what we mean by authenticity, is the way the public perceives it. Here a link can be made between Eco’s proposition and the way Martin Heidegger called attention to the relationship of authenticity to art in his writing on aesthetics.6

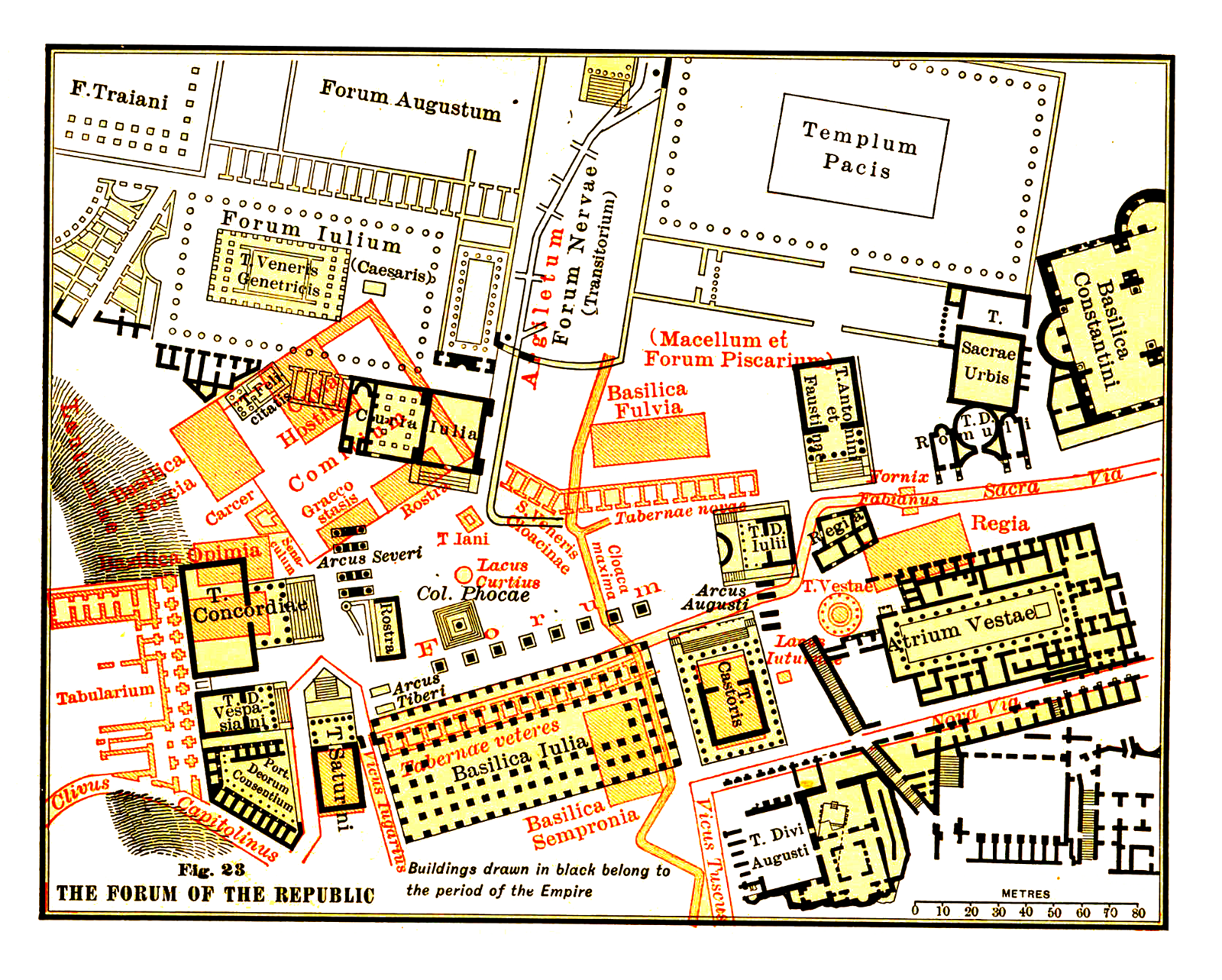

Document and Monument

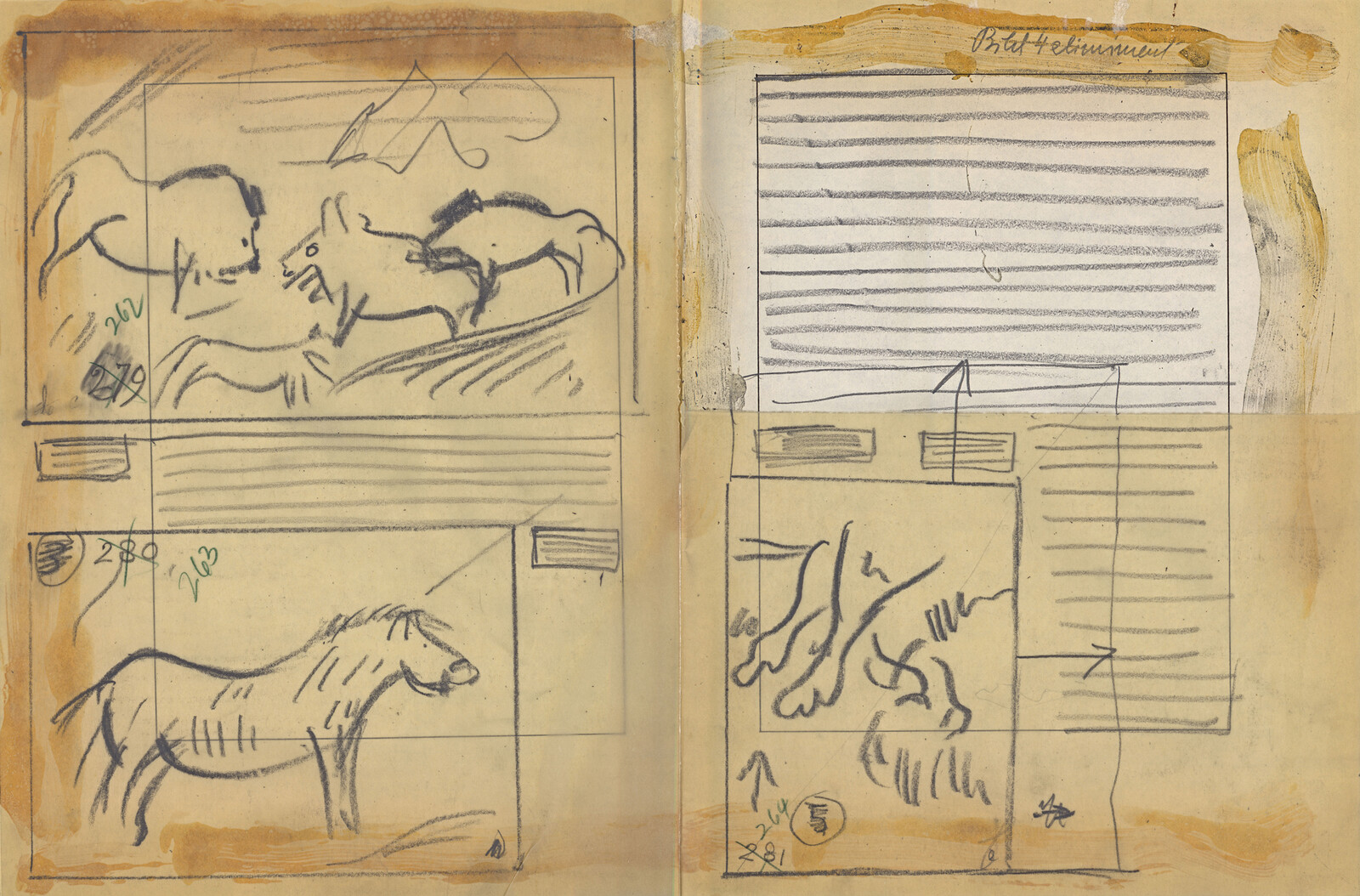

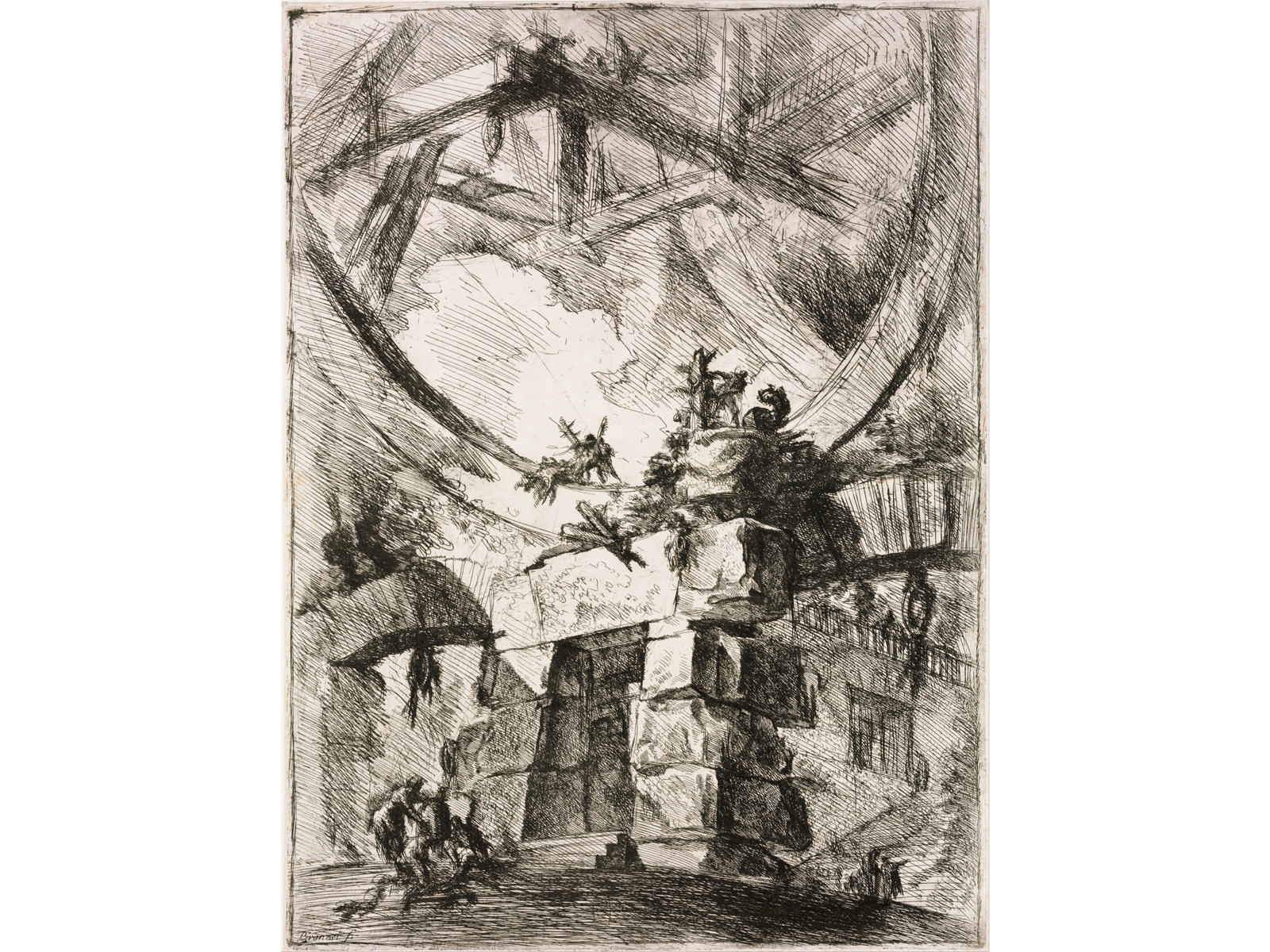

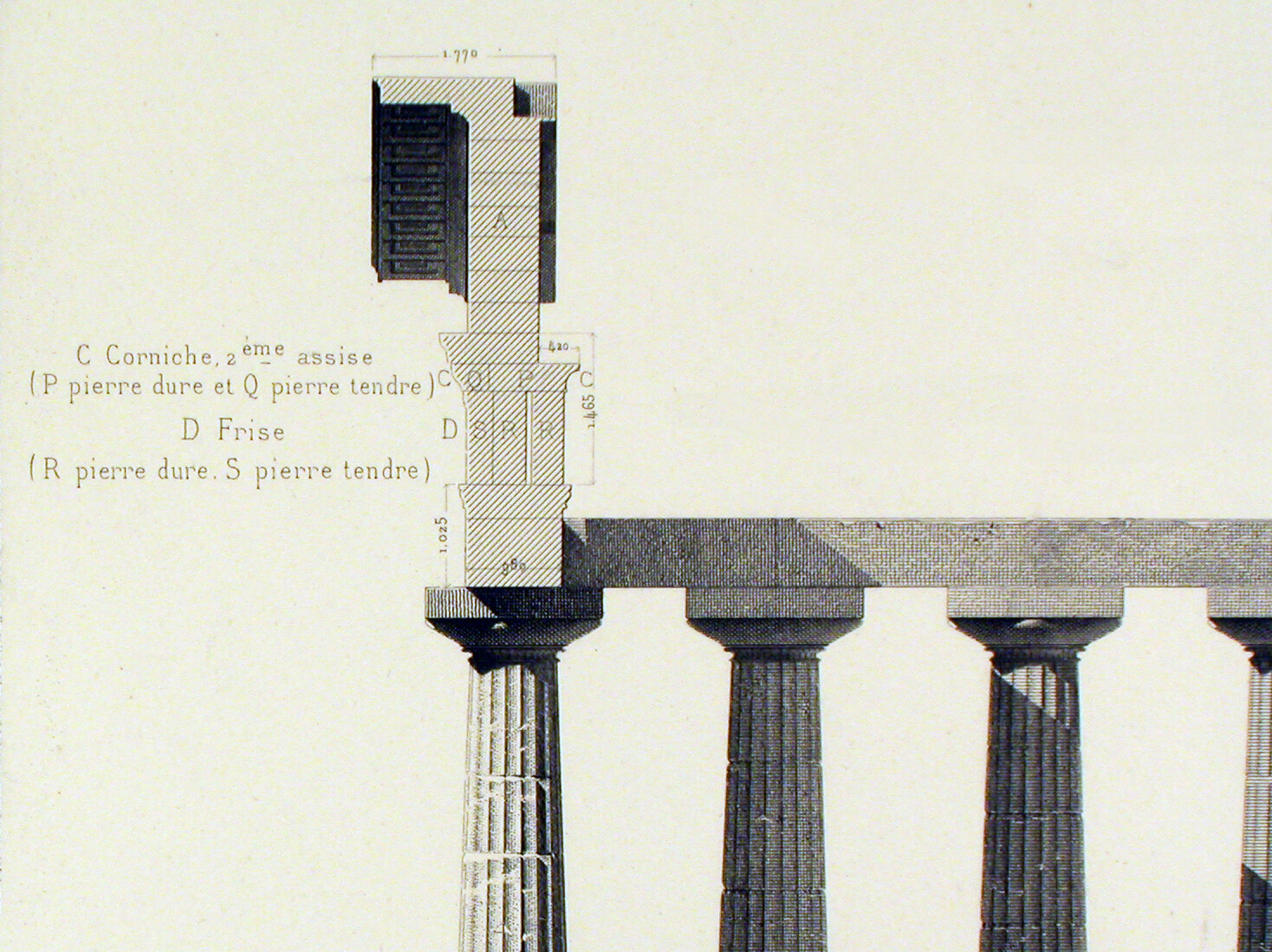

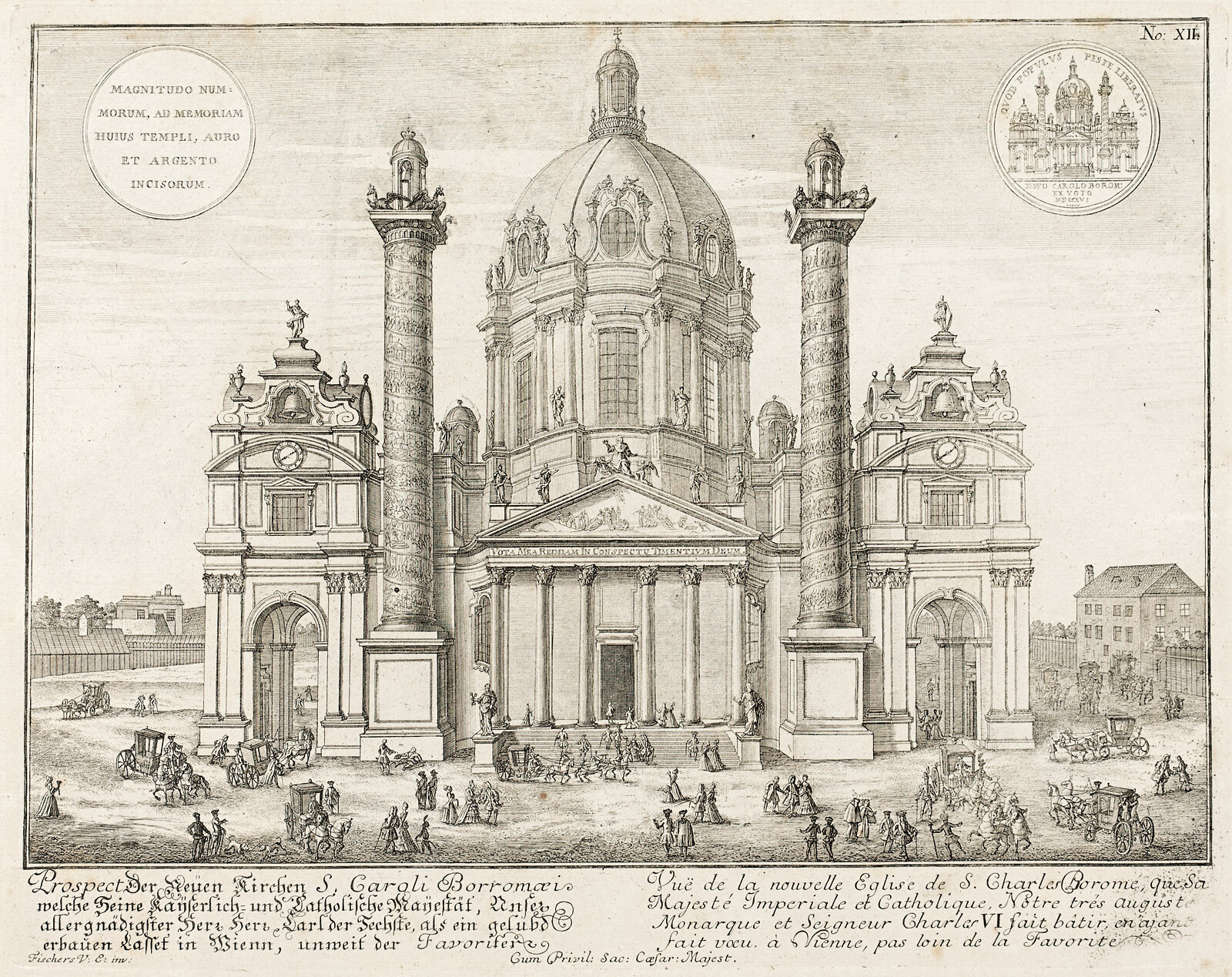

According to French historian Jacques Le Goff, “document” and “monument” are conceptually related.7 Both words share roots in the Latin language. Monument etymologically comes from monere, which means to recall, so monuments are essential tools in the art of memory and act as lieux de mémoire. Document relates to the verb docere, the act of teaching and de facto learning. Therefore, enacting the teaching/learning process, any document, in its written, visual, or built form becomes part of history and consequently of memory. As a matter of fact, any document can be directly referred as a monument. So to say, document and monument form a binary concept, which holds a binomial link to history and memory. This conceptual frame modifies the notion of heritage (and its declination as modern heritage) while establishing new priorities in which the document stands by the monument and substantiates its essential values.

To conclude, it is worth remarking that heritage as subject matter has crossed all the social, cultural, and literary sciences at least for the last thirty-five years. Having introduced the binary relationship document/monument, another possible key to dealing with heritage is the one that binds it with identity.

Heritage evokes beliefs, establishes rules, denies the passage of time, and affirms continuity. One can suggest that heritage exists only as a cultural product. Heritage generates places, as well as identity, mostly as fragments of a history that would otherwise be universal. This is very much the truth for modern heritage, whose season is often short.

A possible declination of heritage and identity also involves the gamut of actors who build the heritage chain and bring the question back to the essence of the games—at time symbolic and power related—conducted to appropriate a space, material, and cultural alike. It is precisely the convergence of heritage and identity practices that helps to explain the use of terms such as “abuse” and “tragedy” in reference to what has rightfully been designated as the fabrication of the heritage. The metaphor of the factory complements that of the assembly line and projects heritage into a productive dimension, fully appropriate for the nature of mechanism and machine that heritage has assumed in our contemporary history.

David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

Pierre Hadot, Régimes d’Historicité: Présentisme et expériences du temps (Paris: Le Seuil, 2003).

This struggle is a common dilemma in developing nations as analyzed by Paul Ricoeur (1913-2005) in his book History and Truth (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1965). Ricoeur’s approach was extensively referred to by Kenneth Frampton in his seminal essay on critical regionalism. See Kenneth Frampton, “Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance,” in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Port Townsend, WA: Bay Press, 1983).

Aloïs Riegl, Moderne Denkmalkultus: sein Wesen und seine Entstehung, (Wien: K. K. Zentral-Kommission für Kunst- und Historische Denkmale, Braumüller, 1903). Translation first published as Aloïs Riegl, ”The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin,” trans. Kurt W. Forster and Diane Ghirardo, in Oppositions 25 (Fall 1982), 21–51.

Umberto Eco, Opera aperta. Forma e indeterminazione nelle poetiche contemporanee (Milano: Bompiani, 1962).

See entries on these subjects in Stanford Enclycopedia of Philosophy.

Jacques Le Goff, “Documento/Monumento,” in Enciclopedia Einaudi, vol. V (Torino: Einaudi, 1978), 38–43.

History/Theory is a collaboration between the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zürich and e-flux Architecture.

History/Theory is a collaboration between the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zurich and e-flux Architecture.