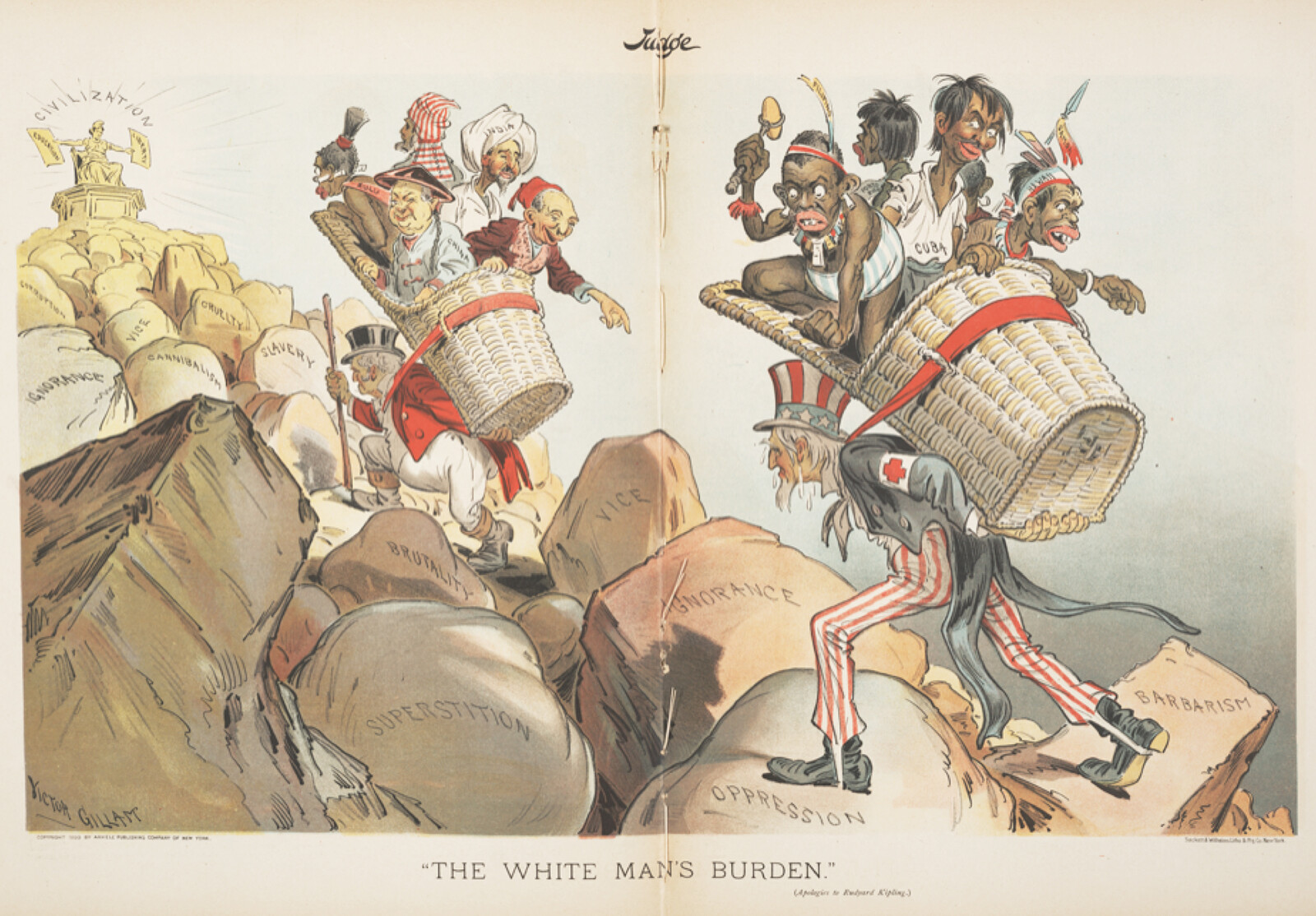

The question what “history” means and why it should be studied is a periodic topic. Ever since Friedrich Schiller treated it in an exemplary way in his inaugural lecture on universal history at the University in Jena in May 1789, it has not ceased to occupy scholarly minds.1 German historian Reinhard Koselleck and sociologist Niklas Luhman both taught us that the image modern society makes of its past is always a contemporary product of its own reflection.2 Thus history, always needing to be rewritten and reshaped, has an open future. This, of course, is a narcissistic mortification to any historian, because it means that their work (as objective as they might think they are) has a temporary character and will never achieve the status of durable truth. If the dimensions of time—past, present and future—do not have any ontological character because they are themselves exposed to temporality, it means that the images of the past and future from past and present societies have to be distinguished. This means that the past’s present is not identical with the present’s past, the contemporary present is something different from the both past’s future and the future’s past, and the present’s future is not the same as the future’s present. The reflexivity of time that Kosseleck and Luhman remind us about allows us to ask: When does history begin? Does it exist before the ascent of modern historiography? And when does it end? When does the present start? With “Modernity”? With the “Post-Modern”? Before? After?

Designing History

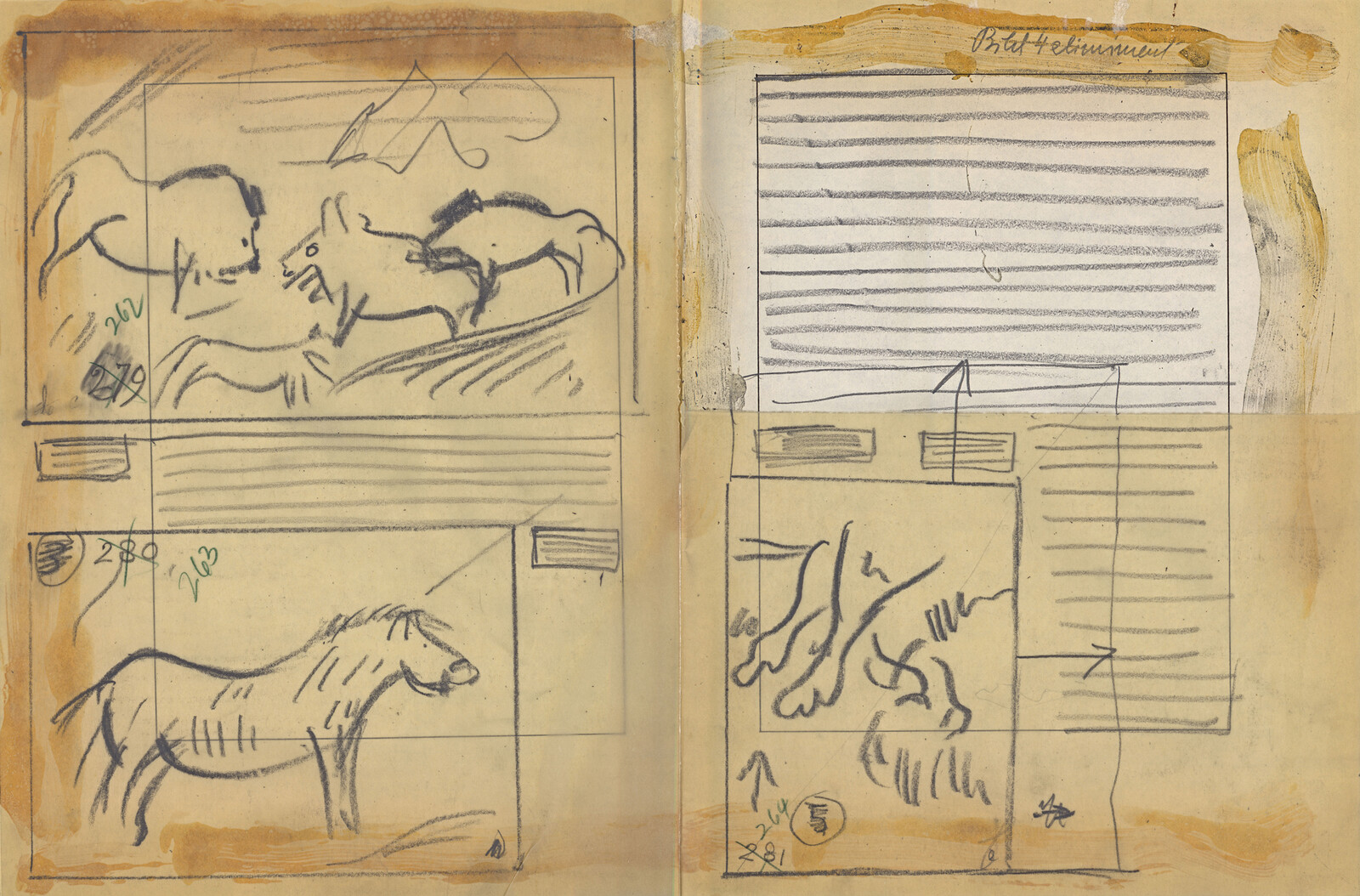

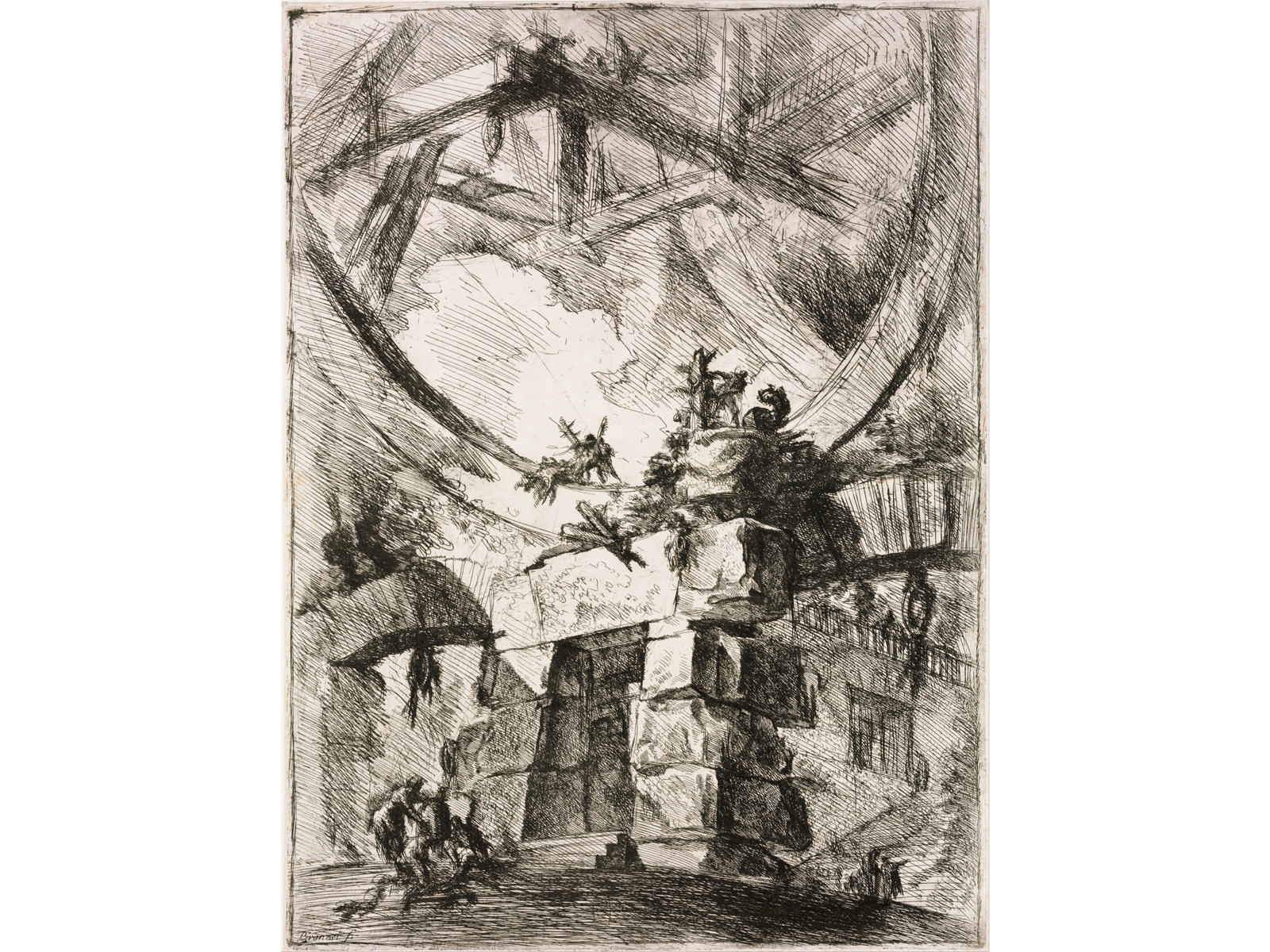

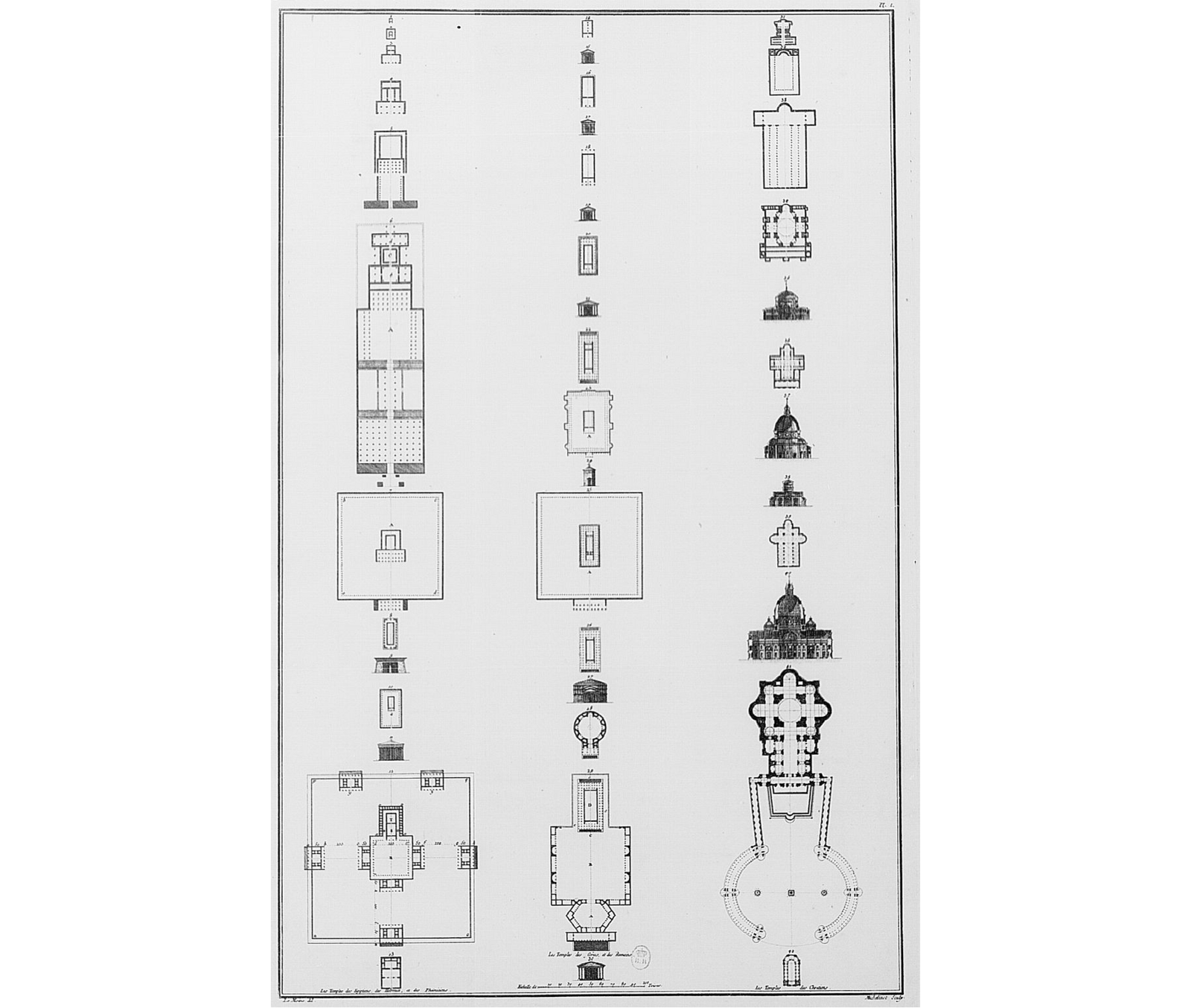

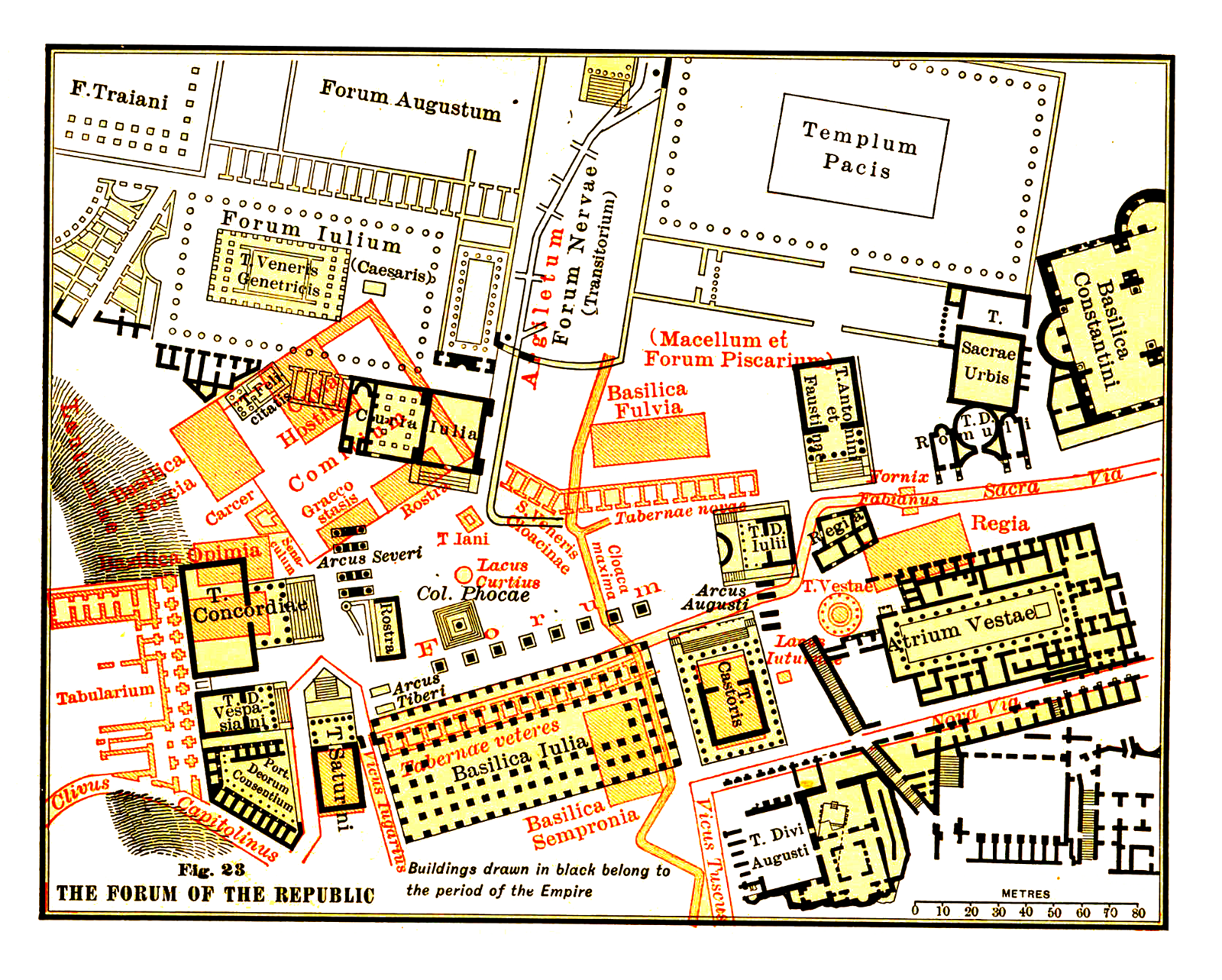

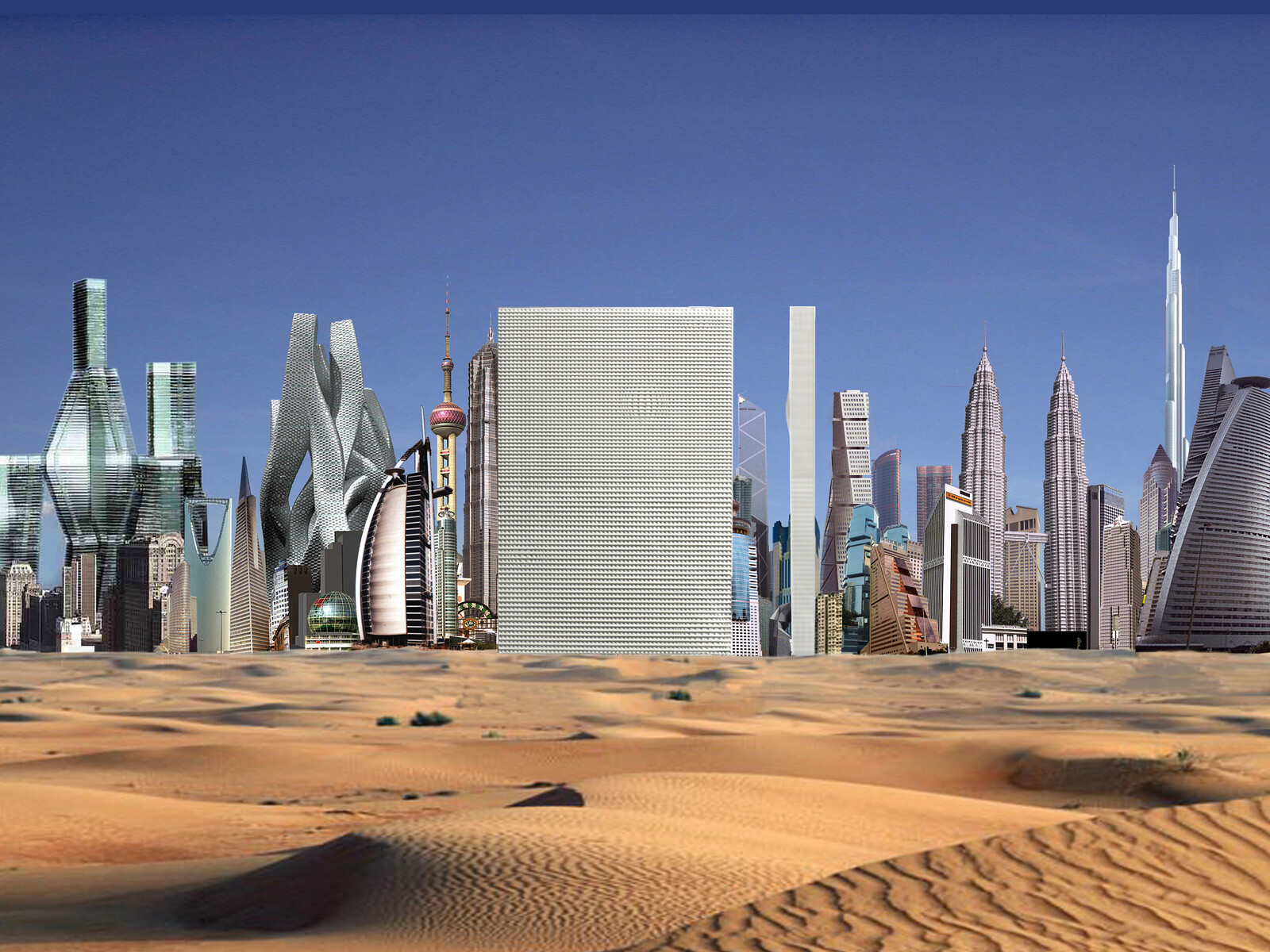

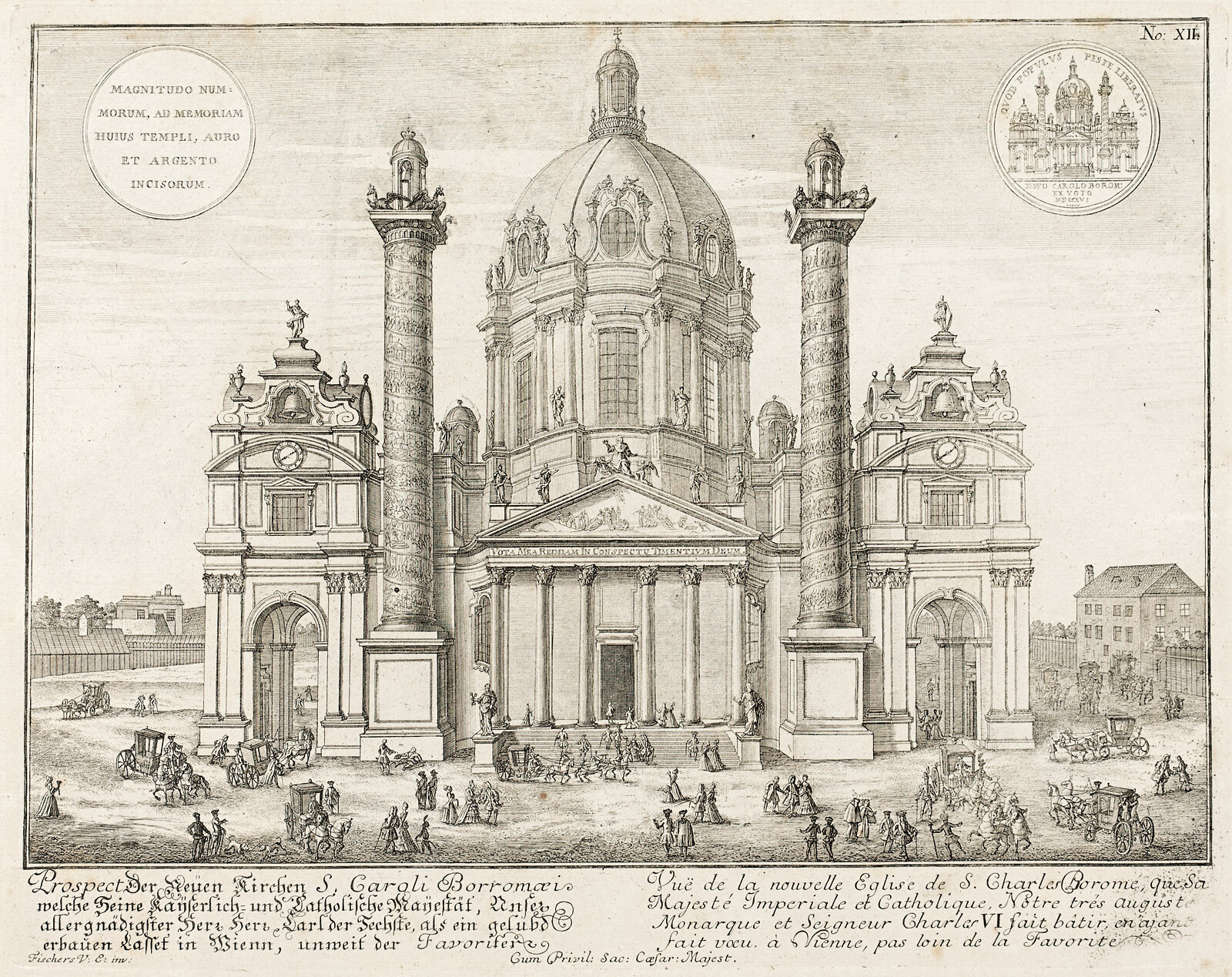

In 1721, Johann Fischer von Erlach published his “Plan of the Civil and Historical Architecture” in Vienna. This book, an engraved architectural history of the buildings and monuments of different ages and civilizations, is considered to be the first pictorial, comparative study of world architecture. Its subtitle reads: “In the Representation of the Most Noted Buildings of Foreign Nations, Both Ancient and Modern: Taken from the Most Approv’d Historians, Original Medals, Remarkable Ruins, and Curious Authentick Designs.” Fischer was soon considered to be “a pioneer as a historian of architecture, for he tried to be archeological as far as the limited knowledge of his time permitted … He was not a scholar in the full sense of the term; he ‘intended,’ so he wrote, ‘to please the eye of the amateur by some examples of different ways of building and to inspire artists to inventions rather than to inform the erudite.’”3 Even though von Erlach claims archeological and philological reliability, his collection of architectural designs, which includes Babylonian, Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Islamic, and Asian examples (as well as some of von Erlach’s own), is tendentious, eclectic, and—excluding any example of French architecture, for instance—selective. Von Erlach was well aware that French architecture under Louis XIV was dominated by national pretensions, and his choice to not include it might have been influenced by that fact. But his own “system” was as well, in that he considers world architecture to provide the ingredients for an imperial architecture, the most impressive result of which is Fischer von Erlach’s own design of the church of St. Charles in Vienna, the Karlskirche.4 We might understand this book as a political statement—which architectural history always is, of course. But we might also learn from it that each generation’s view of the (architectural) past is conditioned, speculative, manipulated, and manipulating, for political, but also, often for purely aesthetic reasons.

Rediscovery

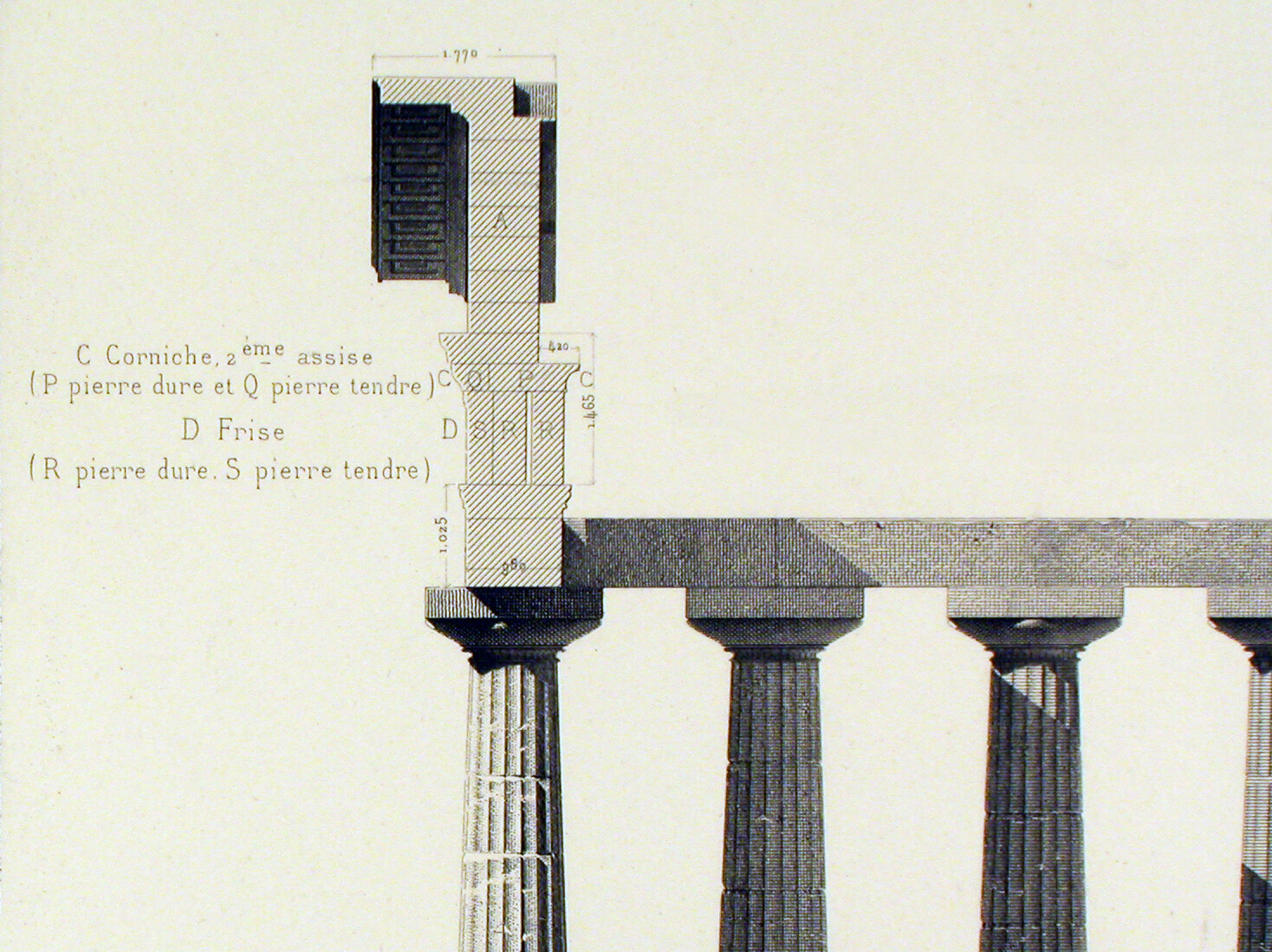

The Temples of Paestum have stood in the region of Salerno since the fifth and sixth centuries BC, but fell into historical oblivion for the large part of their existence. The region was avoided because of malaria, but for as massive as the ruins are, it is undeniable that the temples could have been seen from afar. They were simply “overlooked.” It was only in the mid-eighteenth century that they were “rediscovered,” not because they suddenly re-appeared from the ground, but because the aesthetic sensitivity of the early neo-classical era evaluated them as relevant. After his visit to Paestum in 1750, for instance, the French architect Jacques-Germain Soufflot wondered why the temples had been ignored for such a long time.5 Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the first German to inspect the site in 1758 exclaimed: “Isn’t it astonishing that nobody has written about it?”6 This is just one of many examples that can help to understand how our view of the past is determined by politics, aesthetic selectivity and taste. A more current example of rediscovery is, in fact, the architecture of Andrea Palladio, who unlike in Great Britain, the Netherlands, or the United States, had virtually no historical impact on building practice in German speaking countries until recently. His Four books on Architecture were translated long ago into French and English, but an integral German version was only released in 1983, and was largely spurred by the post-modern turn towards historical architecture.7 If we acknowledge this selectivity, if we better understand the temporality of our own “historical” choices, we might not come closer to historical “truth,” but we can understand more about ourselves and our present. Of course, “history matters,” but it matters in the way we shape and understand it, and critically observe our choices to do so.

Correct?

A brief look at the practice of architectural restoration helps to understand how volatile all certainty in assuming “correct” historical interpretation is. In the last thirty-five years, for example, Palladian Architecture has been re-shaped and restored in many different ways. And at any one time, restorers and historians alike have been convinced to be authoritative on the matter, at least until the next squad of restorers arrived. The question whether brickwork of the Loggia del Capitaniato in Vicenza was buried under stucco or meant to be bare has divided specialists.8 Historical evidence in this case is somehow equivocal. I, personally, would tend to see the façade plastered, so that it would correspond with the Basilica Palladiana standing opposite, Palladio’s radiant white sequence of Loggias—the “Serlianas”—covering the medieval town hall of Vicenza. But currently the bricks are left naked, which produces an irritating effect not only with the more famous neighbor, but with the capitals and bases of the Loggia’s half-columns themselves, worked in stone, like the other elements of its decoration.

Of course, restoration does not only concern the surface. The reconstruction of the Humboldt Forum, the castle of Berlin which was partly destroyed during World War II and torn down in 1950 by the GDR government, currently has tensions running high in German public debate. Is it the version that the architect Andreas Schlüter designed from 1699 on that should be reconstructed, or should the reconstruction be completed according to later interventions, like the central dome, which was executed by Friedrich August Stüler between 1845–1853? And should this dome be embellished by its original cross—despite the fact that no mass will ever be celebrated underneath—or, as the directors of the Forum have already decided, should artworks from beyond Europe be put on display instead?9

Learning

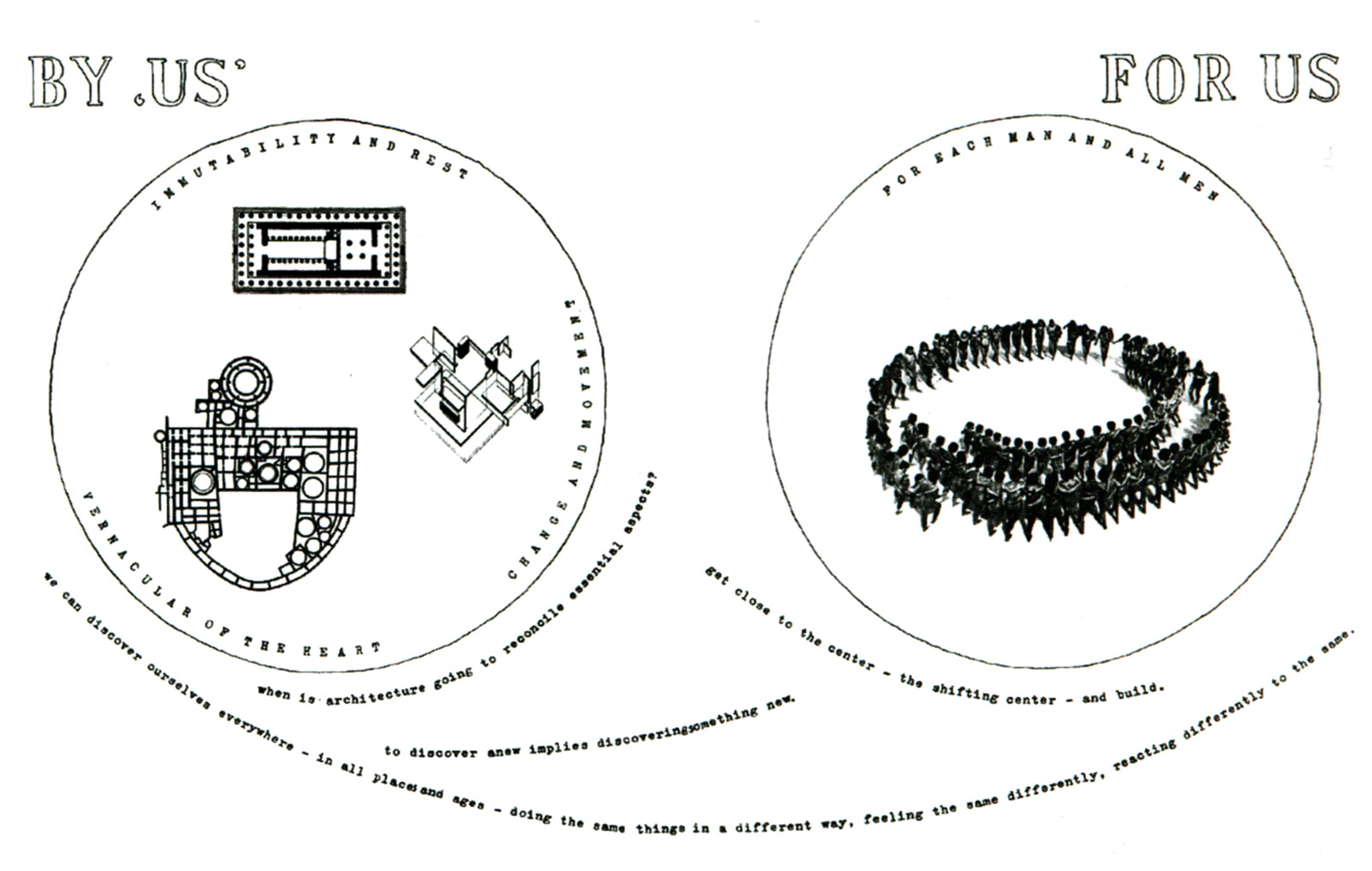

I have never been able to attracted young architects when using the word “history” in the title of my courses. But when calling them “Schauen im Bestand” (“Looking into the stock”), seats were rarely left empty. This subtle shift in name served as an invitation to choose, to look for correspondences, for interesting solutions (aesthetic and practical alike), for elective affinities, without any teleological narrative. It was an avowal of freedom in front of the often-hermetical mass of architectural relics. “History” became astonishingly alive.

Yet from when something can be called “historical” remains a crucial question. After twenty years? Is it a question of generations? Is something historical only when it ceases to exist? But doesn’t Palladio’s Villa Rotonda or his Palazzo Chiericati in Vicenza, di Bartolomeo Michelozzo’s Palazzo Medici in Florence or Mies van der Rohe’s Nationalgalerie exert influence on a young architect’s sensitivity? The non-simultaneous are in simultaneity; the dissimilar are contemporaneous. Yet this is not a new phenomena: we have always been, and always will be in the midst of it. And at the same time, there will always be phenomena and practices that both “exist” and are “historical,” yet without anyone knowing it.

Friedrich Schiller, “Was heisst und zu welchem Ende studiert man Universalgeschichte?” Jena (1789).

Reinhart Koselleck et al., “Geschichte, Historie,“ in Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe 2 (Klett-Cotta, 1975), 539–717; Niklas Luhmann, “Weltzeit und Systemgeschichte. Über Beziehungen zwischen Zeithorizonten und sozialen Strukturen gesellschaftlicher Systeme,” Soziologische Aufklärung 2 (Westdeutscher Verlag, 1975), 103–133. See also: Aloys Winterling, “Antike Antike. Zu Temporalisierungen des griechisch-römischen Altertums,” in Die Präsenz der Antike in der Architektur, eds. Andreas Beyer and Andreas Tönnesmann (Berlin: de Gruyter, forthcoming).

Eberhard Hempel, Baroque Art and Architecture in Central Europe (New York: Viking Adult, 1977), 90.

Hanno-Walter Kruft, Geschichte der Architekturtheorie (München: Verlage C.H. Beck, 2013), 205–207.

Jean Mondain-Monval, Soufflot: Sa Vie, Son Oeuvre, Son Esthetique (Paris: Alphonse Lemerre, 1918), 104.

Susanne Lang, “The Early Publications of the Temples at Paestum,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 13, 1/2 (1950), 48–64.

Andrea Palladio, Die Vier Bücher zur Architektur. Nach der Ausgabe 1570, trans. Andreas Beyer und Ulrich Schütte, (Zürich/München: Verlage für Architektur Artemis, 1983).

M.T. Franco, “Tra conservazione e restauro: progetti tra Otto-Novecento per opere palladiane,” in Andrea Palladio. Il testo, l’immagine, la città, catalogo della mostra, ed. Lionello Puppi (Milano: Electa, 1980), 93–94.

The Humboldt Forum, which Italian architect Franco Stella and his collaborator Michelangelo Zucchini are going to complete soon, will teach us a lot about contemporary handling of historical architecture. See Andreas Kilb, “Eine neue Symboldebatte um das Humboldtforum,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (May 24, 2017), ➝.

History/Theory is a collaboration between the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zürich and e-flux Architecture.

History/Theory is a collaboration between the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zurich and e-flux Architecture.

.jpg,1600)

.jpg,1200)