All of architecture took on the same utopian idea, where each new building became a blueprint for utopia in the future, but ultimately was in competition with the city, and with every other building.

—Dan Graham1

1.

Architecture is the art of creating objects that distinguish themselves from their environment and from the mere production of buildings. As a definition, it seems obvious enough: different from what exists, architecture summarizes cultural problems spatially and functionally. This allows architects to work critically: they don’t just do what is expected, but they are stubborn enough to reject options, point out alternatives, or reveal what wasn’t visible. Rather than appearing as one of many products from the culture industry, a building can show a way out of dominant and troublesome practices. In a conversation from 2000 with Jean Nouvel, Jean Baudrillard said: “A work of art is a singularity, and all these singularities can create holes, interstices, voids, et cetera, in the metastatic fullness of culture.”2 Nevertheless, Baudrillard was pessimistic: when nearly everyone has become a cultural producer, when almost everything is incorporated or encapsulated, and spectacular in nothing but tame and superficial ways, the singular is not easy to accomplish. “We are stuck in an unlimited, metastatic development of culture, which has heavily invested in architecture. But to what extend can we judge it? Today it’s very difficult to identify, in a given building, what belongs to this secret, this singularity that hasn’t really disappeared. I think that as a form it is indestructible but is increasingly consumed by culture.”3

2.

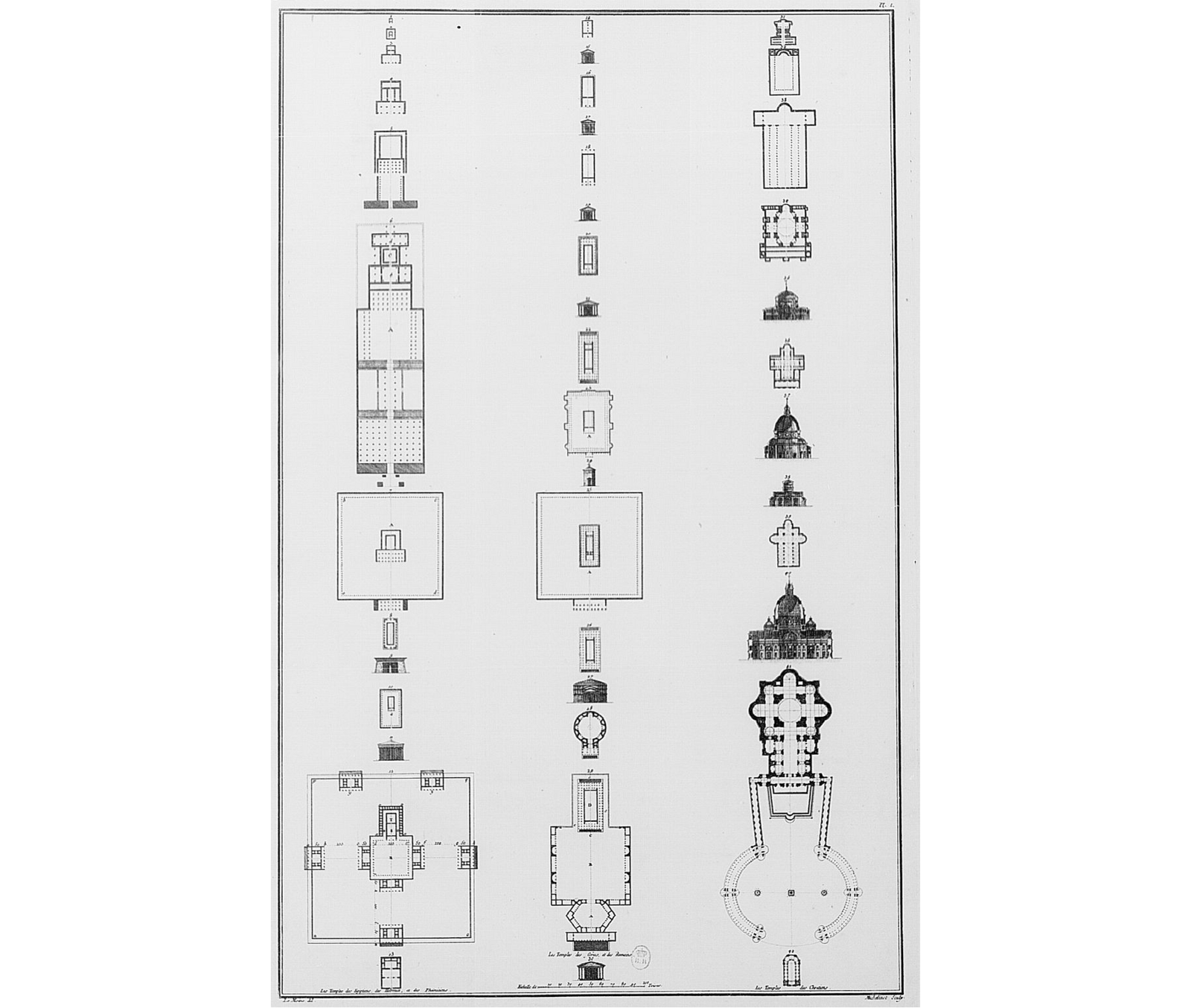

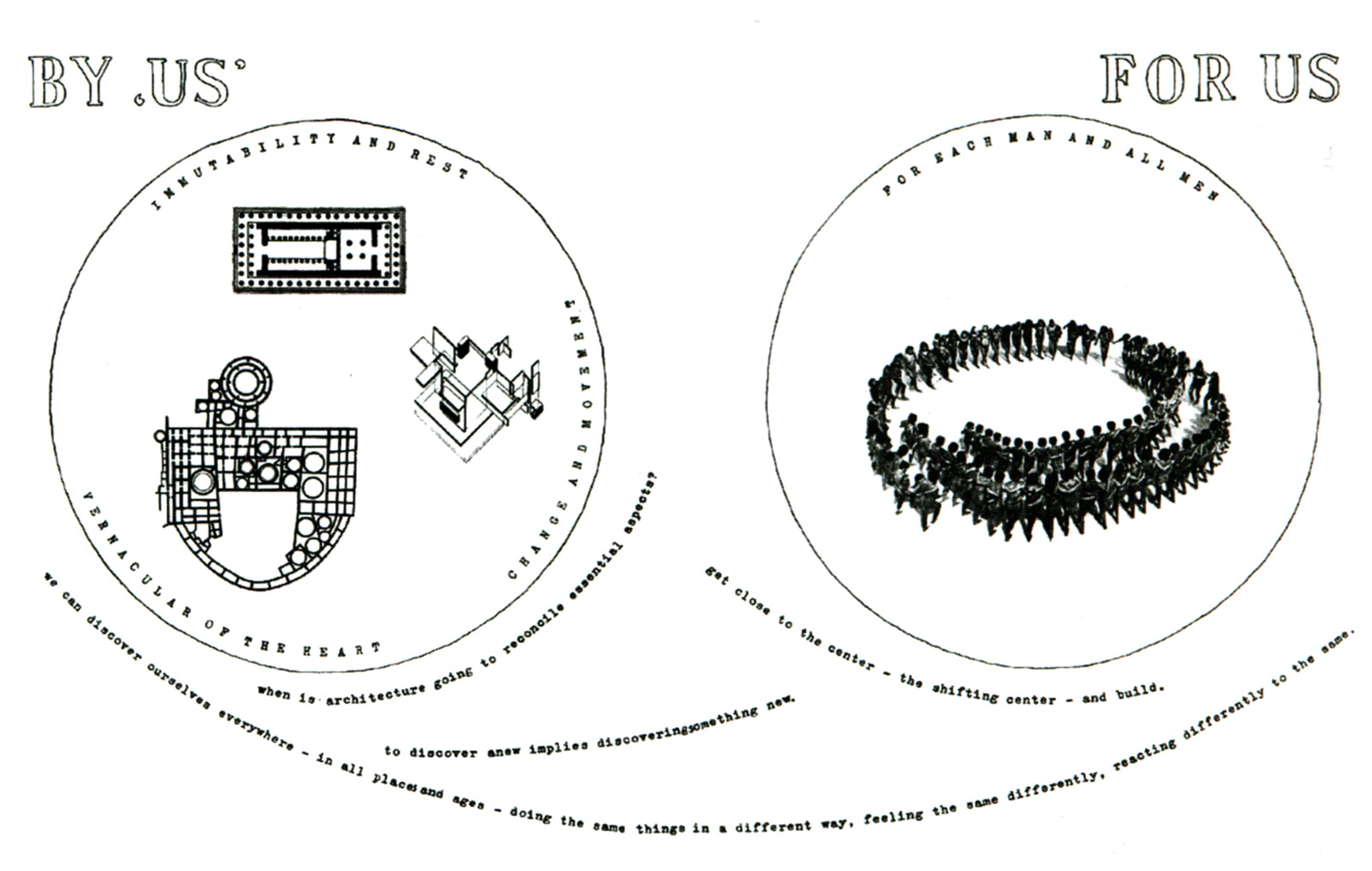

Postwar architects have largely worked within this tradition of accomplishing, with each building, something completely different. Three theories from the sixties, written by prolific architects, illustrate this. Although large discrepancies exist between the work of Aldo Rossi, Rem Koolhaas, and Aldo van Eyck, they did agree on one thing: architects create places, spaces, and interruptions in the urban tissue, which is not “woven” by architects but that comes about, seemingly naturally, throughout history. Cities are not designed as coherent wholes, but they do benefit from punctual interventions.

In The Architecture of the City, first published in 1966, Rossi wrote about the importance of “the individuality of urban artifacts” and those aspects of urban reality that “are the most individual, special, irregular but therefore also the most interesting.” Only singular buildings can, according to Rossi, help to avoid “artificial and superfluous theories.”4 Aldo van Eyck had something similar in mind when in 1962 he emphasized the importance of impressive but useful places because they interrupt urban monotony. These “identifying devices,” Van Eyck wrote, “should be structurally bolder and far more meaningful than those which satisfy architects and urbanists today. They must, above all, be of a higher order of invention, so that the congeniality and human immediacy of the small, intimate configuration can become of a higher order through them.”5 Yet these devices, Van Eyck warns, tend to lose their power over time, which is why it is necessary to continually “invent” new ones—the raison d’être of architects.

That architecture doesn’t stay unique, and that cities need new buildings that attract everyone’s attention, is something that Koolhaas has also stressed, when he opened a 1969 text entitled “The Surface” with these sentences: “A city is a plane of tarmac with some red hot spots of urban intensity. These red hot spots radiate city-sense. If not taken care of properly, it tends to quickly ebb away.”6 For a long time, this remained the central question in Koolhaas’s writings, from Delirious New York to “Bigness” and “Genericy City”: how can buildings reinvigorate the city? How can architecture escape from predetermined meanings and become something fascinating that provokes interpretation? How can it be avoided that a city becomes generic, exchangeable, empty and meaningless? And how can architecture be new? Ever since 2000 with “Junkspace” he may have lost his faith, but during the nineties Koolhaas still kept an eye open to contemporary buildings conceived by architects for their potential to intervene in the city. At a conference in Delft in 1990, he presented Il Palazzo, a hotel recently designed by Aldo Rossi in Fukuoka, Japan, by saying: “though shocking and not particularly attractive, still I have yet to see another recent building that makes such astounding and ingenious use of the cultural and technical potential of a given moment.” The building is a closed, threatening, and towering volume with a massive, blind facade, composed of red columns and zinc green beams. Koolhaas emphasized how this building was positioned in a “typically Japanese piece of town: one totally chaotic layer of bamboo,” which made its uniqueness as an architectonic exception in the growing chaos of Fukuoka its most important characteristic.7

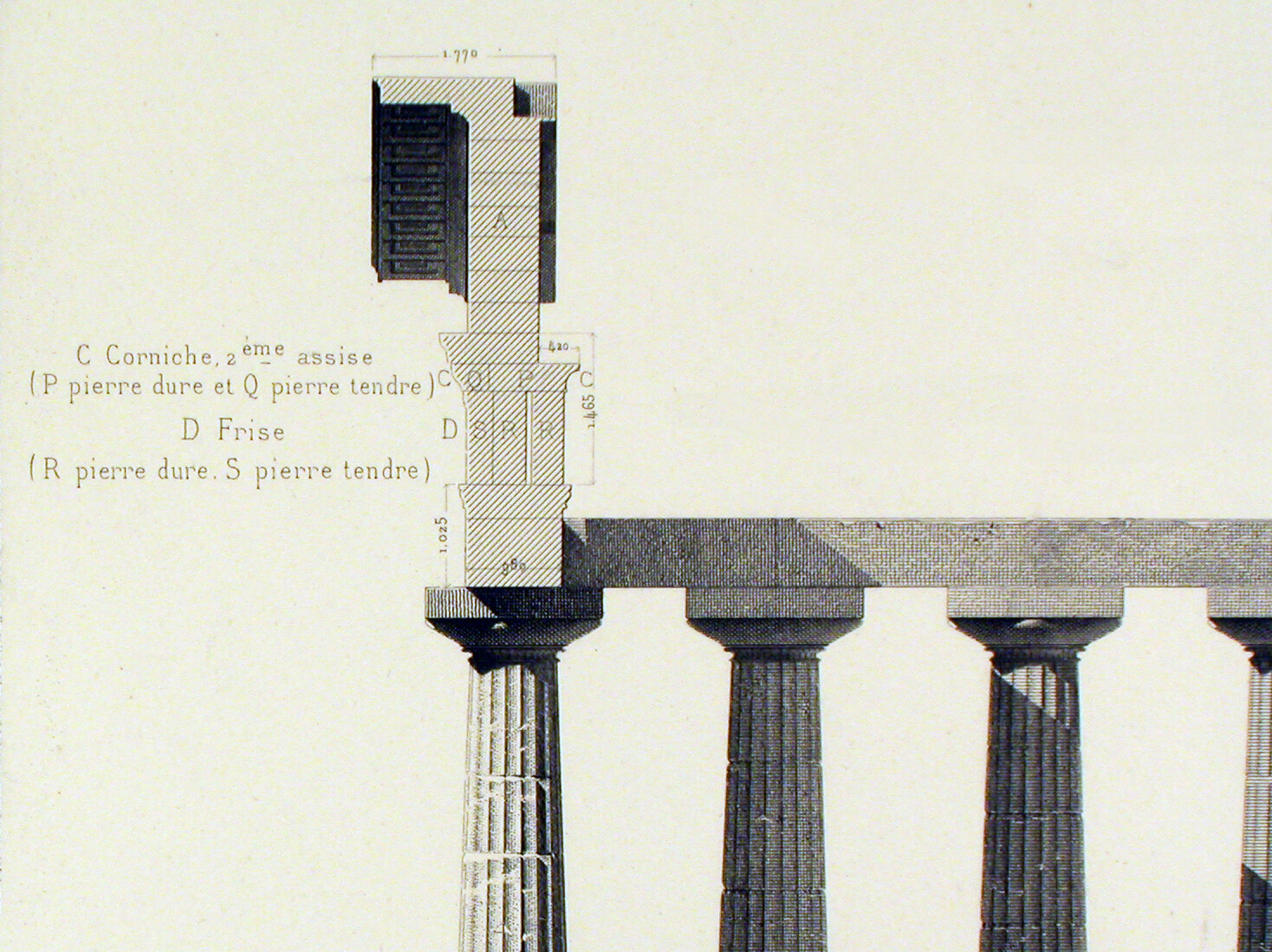

architecten de vylder vinck taillieu, l-o-ke-renn, 2008.

3.

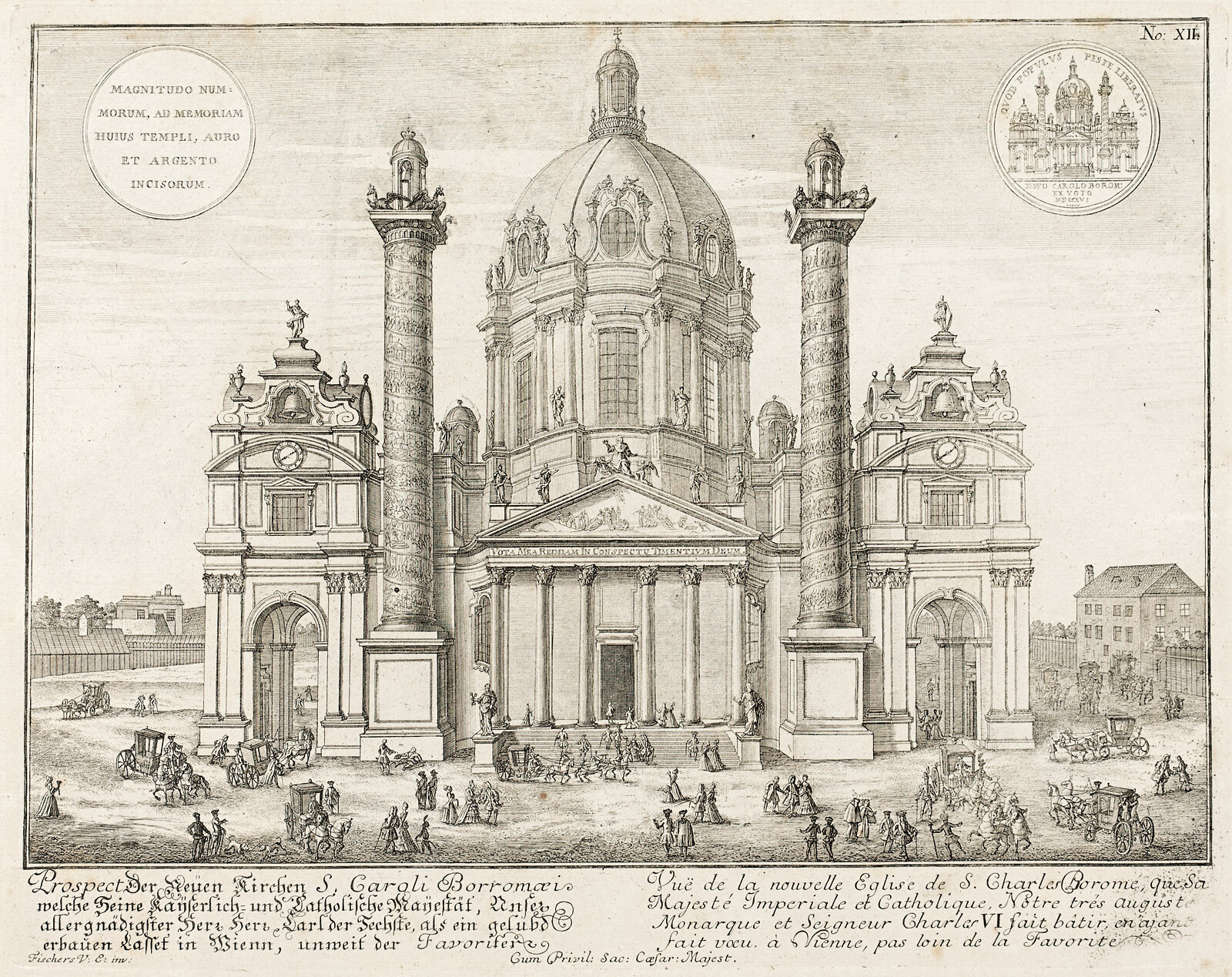

Rossi connected the value of urban artifacts with religious places in the way they derive their character from “a particular event that occurred there at some time or an infinite variety of other causes, both rational and irrational. Even within the universal space of the Church, there is still an intermediate value that is recognized and sanctioned, the possibility of a real—if extraordinary—idea of space.”8 Rossi affirmed that this “idea” can be connected with the uniqueness of urban artifacts, because it is not easy to explain how these exceptional spaces “function” or manifest themselves.

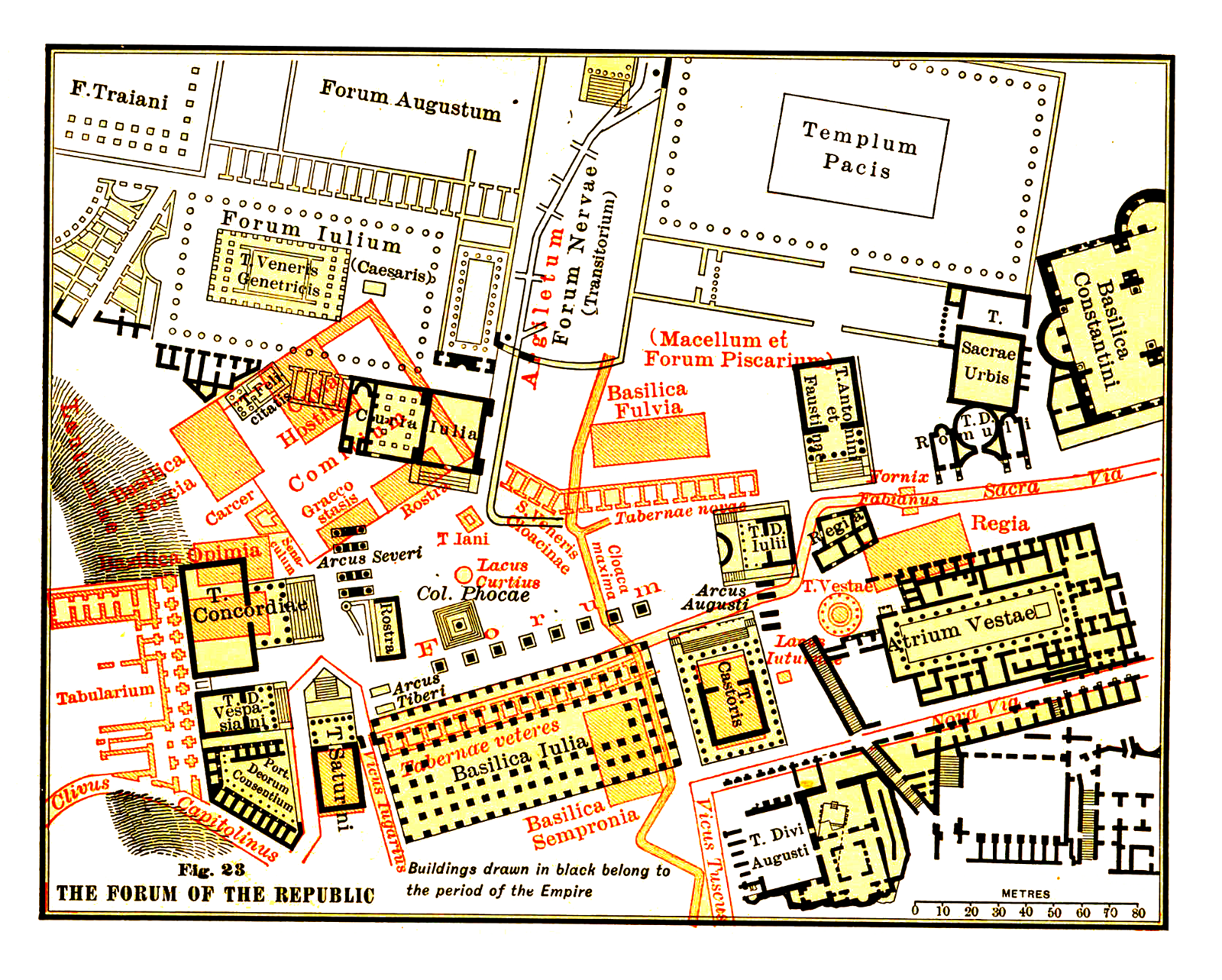

The experience of a singular place is essential for the practice of religion. According to Mircea Eliade, religious life takes place in a world that is ordered thanks to the distinction between the sacred and the profane.9 This distinction that establishes itself spatially, such as in the case of a medieval city with its chaos of houses and streets, yet one collectively shared center: the church. Without places that are valuable and important for everyone, the world becomes incoherent, unreadable and frightening: “In the homogeneous and infinite expanse, in which no point of reference is possible and hence no orientation can be established, the hierophany reveals an absolute fixed point, a centre.”10 Eliade emphasized how this experience is part of everyday life: “In each case we are confronted by the same mysterious act—the manifestation of something of a wholly different order, a reality that does not belong to our world, in objects that are an integral part of our natural ‘profane’ world.”11

The times in which cities were collectively organized around a church belong to the past. But that environments in which people live are ordered by the desire for collectivity and for architectonic objects, can—following Eliade—be considered essential, for even the daily life of the most “advanced” people is determined by events, places and patterns with a religious kernel: “The majority of the ‘irreligious’ still behave religiously, even though they are not aware of the fact.”12 Using or “reading” modern architecture and having a religious experience, are in this sense part of the same tradition. The critical value that Baudrillard attributed to architectonic objects is even a remnant of this, insofar as it deals with the recognition of a place that is different than the norm, the lifestyle or the current fashion, for which reason becomes meaningful and directional.

4.

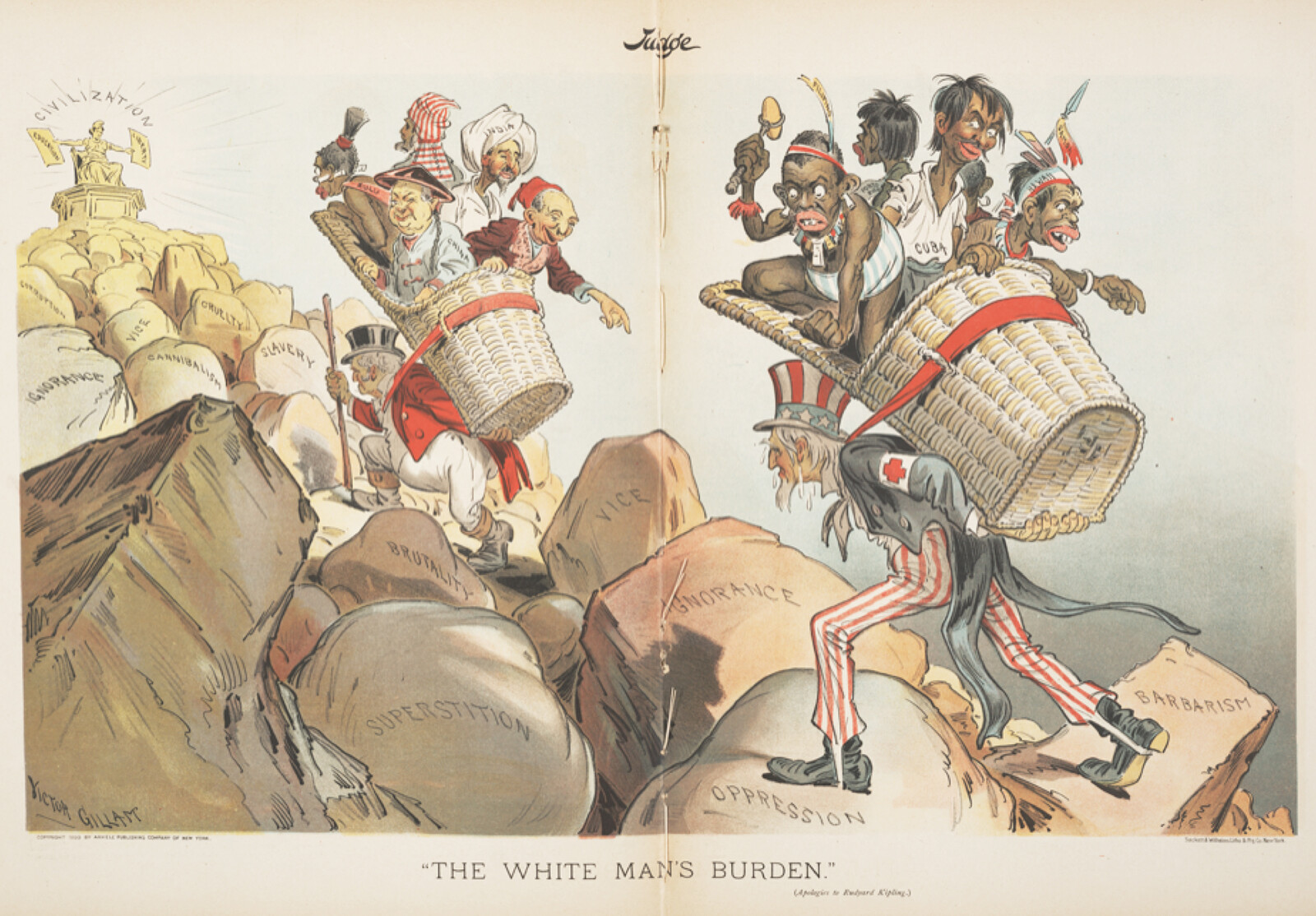

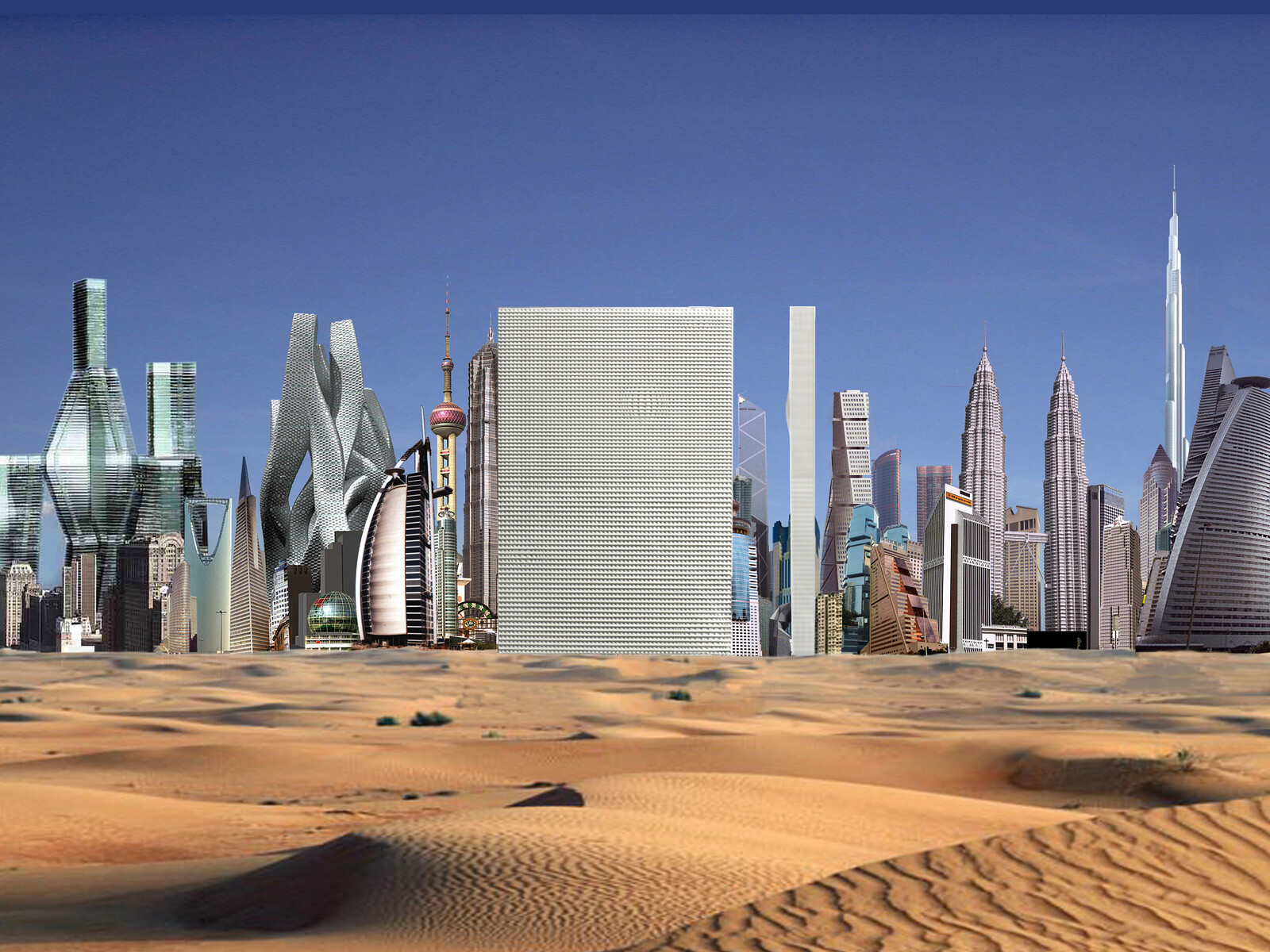

Isn’t it naive to think that some buildings not only have a collective character, but also, at the same time, a different or critical value? How can you collect people according to a crypto-religious logic if they are individuals unbound by rules or goals, only interested in their own well being? And what is the value of a center, an urban artifact, an identifying device, or a hotspot when cities become reduced to factories of the spectacle, collections of spaces that offer themselves as experience—unique, special, unmissable, and unforgettable? Architecture no longer makes a difference, simply because there is too much difference, too much architecture around. But architecture also no longer makes a difference because it no longer stands to change or reorganize life.

Eliade expressed that “Modern man’s ‘private mythologies’—his dreams, reveries, fantasies, and so on—never rise to the ontological status of myths, precisely because they are not experienced by the whole man and therefore do not transform a particular situation into a situation that is paradigmatic. Modern man’s anxieties, his experiences in dream or imagination, although ‘religious’ from the point of view of form do not … make part of a philosophy of life.”13 In other words, whoever tries to bring a collectively experienced order into cities by means of architecture is living in a fairytale rather than reckoning with and expressing the characteristic of modern, contemporary life. “Properly speaking,” Eliade admits, “there is no longer any world, there are only fragments of a shattered universe, an amorphous mass consisting of an infinite number of more or less neutral places in which man moves, governed and driven by the obligations of existence.”14

If anyone has made an architectural critique of singularity that can be deduced from this understanding of what it means to live today, it would be Manfredo Tafuri, when he looked back on the modern movement, criticized the possibilities for communication of postwar architecture, and recognized its emptiness. In writing about the work of Ludwig Hilberseimer in 1973, Tafuri wrote: “Architecture loses it specific dimension, at least in the traditional sense. Since it is ‘exceptional’ in respect to the homogeneity of the city, the architectural object is completely dissolved … The architect as producer of objects has indeed become an inadequate figure.”15 For Tafuri, it was because of this that twentieth-century architects became cynical opportunists, neo-expressionist sculptors, or unworldly blusterers. He used Benjamin’s concept of aura to claim that buildings no longer have an auratic singularity. The traditional definition of architecture has been abolished, and Tafuri suggested that architects should remove the building-as-an-object from their considerations and instead—as Hilberseimer did—try to find ways of imagining the whole city as a process.

5.

Despite its damnation and critique, the unique object is still a means of intervening into the city at large, and on a theoretical level as well. Elia Zenghelis summarized this in 2007 as “acupuncture with a big needle,” and the work of Pier Vittorio Aureli can read in a similar sense, yet one in which singularity is defined not therapeutically but politically; as a realization of an agonistic struggle, and as a withdrawal from everything that is urban.16 But the question remains whether this split regarding the agency of architecture’s singularity doesn’t change due to the qualitative difference of cities and society in the twenty-first century. One major, undeniable difference is the existence of a digital culture of images and the idea of a “global architecture,” in which the internet serves as both the context and prominent site for dissemination of production. Although the web hasn’t replaced the city as a working and living environment, it does increasingly impose its logic. Regardless of whether architects are trying to rescue or to escape singularity, their work ends up in an infinite reservoir of images in which unique buildings are transformed into generic images, and vice versa. But the normalization of singularity this entails is not just a feature of the contemporary moment; it is also fundamental for modernity. Think of Kafka’s passage in The Trial in which the painter Titorelli presents K. with a beautiful landscape, and when K. likes it, he receives another one, and another one, and another one, ad infinitum. Titorelli’s studio is full of beautiful landscapes, but in the end, all of them are identical. “In the time of hell,” Benjamin wrote in reaction to this scene, “the new is always the eternally selfsame.”17 Is architecture in the twenty-first century merely the art of creating images that feed our endlessly attentive appetite for distraction, for a newness that never changes anything?

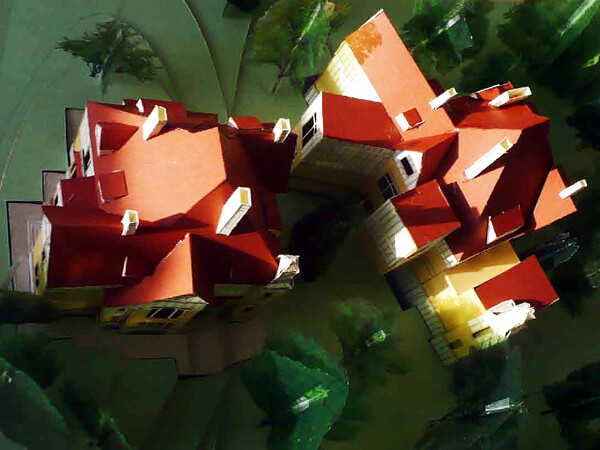

architecten de vylder vinck taillieu, bern heim beuk, 2011. Photo: Filip Dujardin.

6.

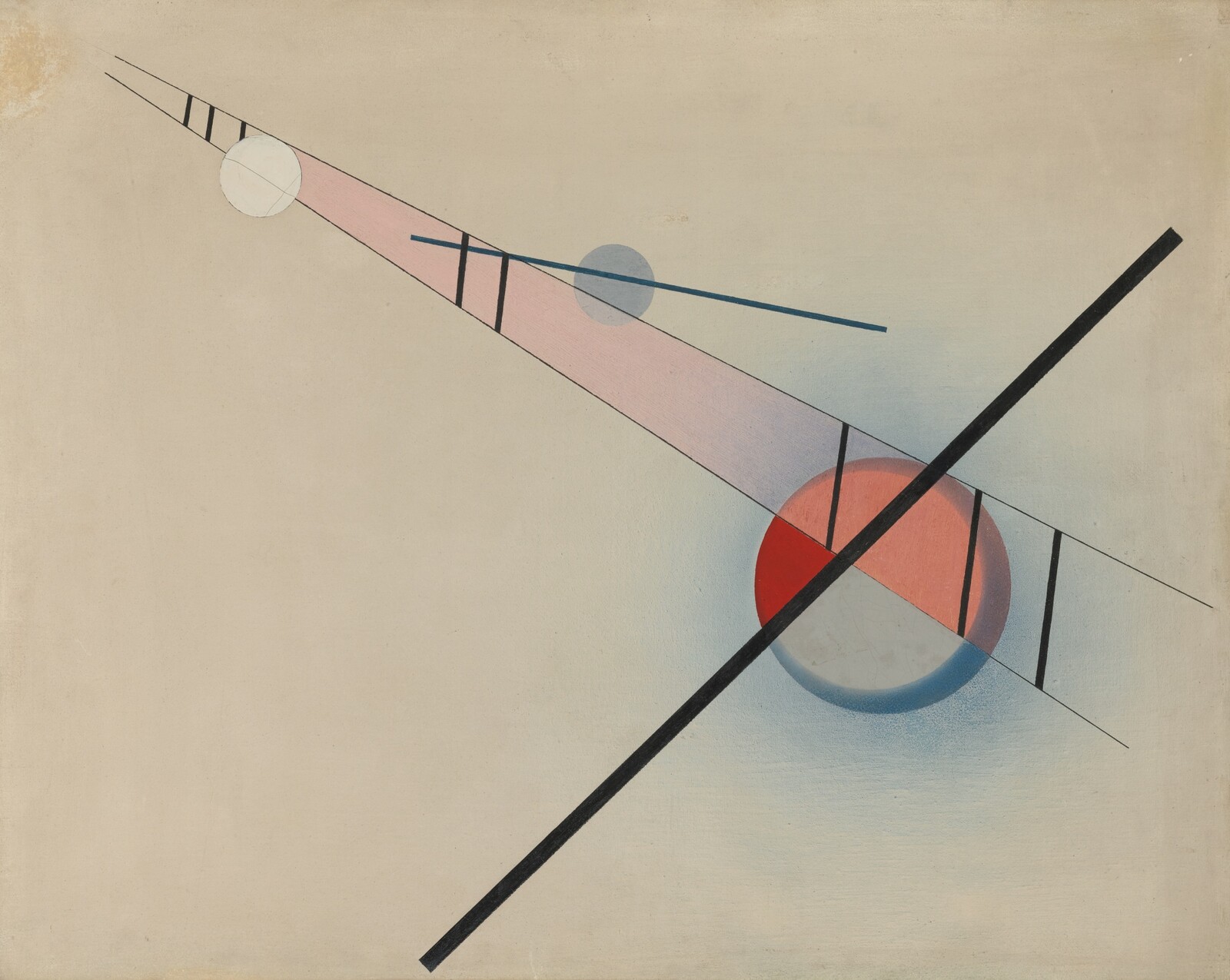

If singularity is the originary architectural thesis and the generic is its antithesis, their synthesis may be something like a secret or silent singularity, one that subtly exposes its own conditions without destroying the system within which it operates. Two contemporary practices, both originating in Belgium, illustrate what an silently singular architecture might be.18 The work of architecten de vylder vinck taillieu (advvt) can incite peevishness because of the way complexity is produced often artificially. Nearly every aspect of their buildings become manneristic, such as colorful collages of “wrong” or vernacular elements that are transformed or “misused,” yet comes together in an intriguing form that remains functional. As Kersten Geers has written, advvt have a particular way of dealing with the cultural or physical surroundings of their buildings. Instead of trying to heighten contrast, they appropriate what is present: “the context itself becomes the project, or at least part of the project. If the context is redrawn, it is transformed and taken over.”19 Emblematic of this is bern heim beuk, where a large tree becomes part of a house—not inside a patio, like in Lina Bo Bardi’s Glass House, but as a brutal interruption. It is as if the house was there first, and the tree grew through it, breaching the roof. At the same time, the main structural element of the house is a concrete column with beams as branches, modelled on the existing tree. The architects play humorously with the absurdities of architectural invention. Seeking out the singularity of their projects literally means defining what is different (and what is new) and what not; what did the architects devise, what was already there, and what did they simply take over from the context? These questions are also provoked by an unexecuted project for a music conservatory from 2008, entitled l-o-ke-renn, in which the existing building—a villa from the late-nineteenth century—is used as a model to build another one, accurately copied but slightly improved. In the end, two objects come about, and the obligation to build “surprisingly,” is teasingly evaded by producing the seemingly selfsame.

7.

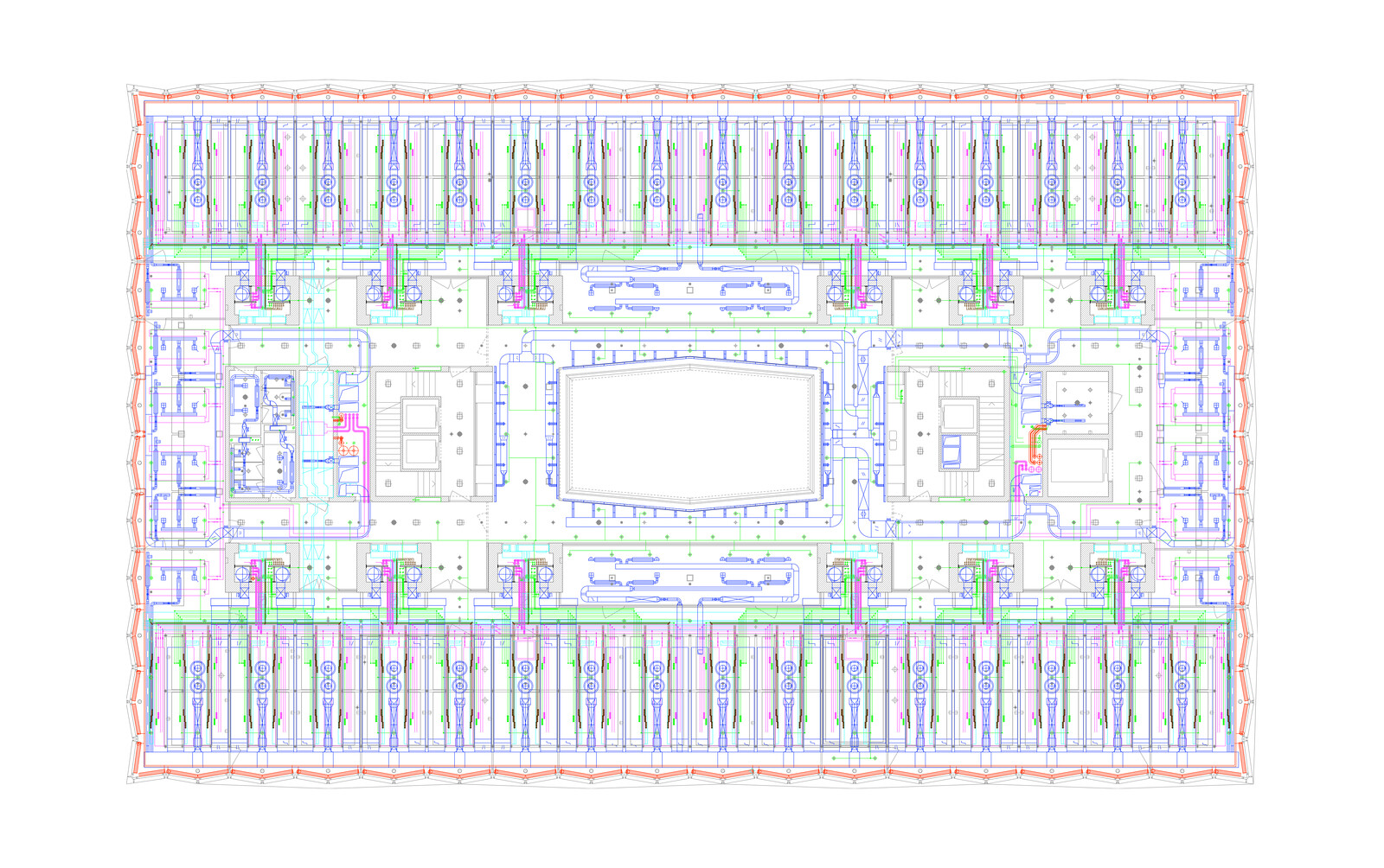

The practice of OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen is in this sense diametrically opposed: where advvt tries to confuse and ironize the conditions of its own authorship by blurring the boundaries between old and new, the work of OFFICE is as precise as possible and unmistakably the result of an explicit intention on which no doubt can exist. What is obvious is strengthened instead of avoided, and the clarity of the projects is not there for functional or technological reasons, but because of the own internal, formal and compositional logic. Their architecture works within the tension between a chaotic world without order and a small and clearly defined cutout in which only architectonic rules seem to be valid. This does not mean that absurdities or incompatibilities don’t occur. On the contrary, OFFICE marks out a small zone in which they will operate and then they stage the clash between their own nearly classicist method and the obstinacy of the context, which does not, will not, cannot simply adjust itself to the will to form of the architects. OFFICE 61, an office building in Kortrijk, might by now be a classic example of this relationship between architecture and the city. Conceived in a V-shape, the building frames the landscape with a glass façade facing the street. The first floor of this almost platonically perfect object is, however, seemingly buried inside of the sloping terrain, as if the context hasn’t been a consideration at all. Here, singularity is achieved by means of compositional perfection, but also by the inclusion of the moment in which the desire for harmony crashes into the contingencies of reality. Another example is OFFICE 45, Kortrijk XPO, a disordered exposition complex unified and framed by a rectilinear gallery running around its perimeter. A small entrance building has its own compositional grid, but its façade trapped within the frame of the gallery, resulting in a white beam passing in front of the windows. When I visited this project some years ago, an architect I was with honestly thought that this was an unintentional and unforgivable mistake—a result of the rigid formal assumptions of the architects that weren’t brought to a successful conclusion.

Whereas in the work of addvt the logic of architectonic singularity is brought about by doing what seems so strange that it is often no longer recognizable as architecture, the projects of OFFICE restore difference by faithfully using the generic elements and compositional methods of the modernist canon, even if it may lead to apparent—but of course carefully staged—mistakes. In both cases, architecture is not just simply a cultural product, but also a work that transcends by affirming the constraints of contemporary architectural praxis.

Dan Graham, Two-Way Mirror Cylinder Inside Cube and a Video Salon (New York: Dia Art Foundation, 1992/2017).

Jean Baudrillard, Jean Nouvel, The Singular Objects of Architecture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), 20-21.

Ibid., 20.

Aldo Rossi, L’architettura della città (Venezia: Marsilio, 1966), 8.

Aldo van Eyck, “Steps Towards a Configurative Discipline”, Forum 16, no. 3 (1962): 93.

Gabriele Mastrigli, “Modernity and Myth: Rem Koolhaas in New York”, San Rocco 4, no. 8 (2013): 86.

Rem Koolhaas, “How Modern is Dutch Architecture?” in Mart Stam’s Trousers. Stories From Behind the Scenes of Dutch Moral Modernism, Crimson, Michael Speaks, and Gerard Hadders eds. (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 1990), 165–166.

Aldo Rossi, The Architecture of the City (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1982), 103.

Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and The Profane (New York: Harcourt, 1957).

Ibid., 21.

Ibid., 11.

Ibid., 204.

Ibid., 211.

Ibid., 23-24.

Manfredo Tafuri, Architecture and Utopia (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1976), 105–107.

Elia Zenghelis, “For A New Monumentality,” in Pier Vittorio Aureli, Brussels, A Manifesto. Towards The Capital Of Europe, ed. Véronique Patteeuw, Joachim Declerck, Martino Tattara (Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2007), 226; Pier Vittorio Aureli, The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011). On Dogma, see: Christophe Van Gerrewey, “How Soon Is Now? Ten Problems and Paradoxes in the Work of Dogma”, Log 35 (2015), 27–47.

Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (Cambridge: The Belknapp Press of Harvard University Press, 1999), 548.

On OFFICE, see also: Christophe Van Gerrewey, “Order, Disorder. Ten Choices and Contradictions in the Work of OFFICE”, in: OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen. Volume 2, ed. Ellis Woodman (Köln: Walther König, 2016), 7–14. On advvt: Christophe Van Gerrewey, “Hard to Explain. Ten Opinions and Misunderstandings about the Work of advvt,” 2G 66 (2013), 5–13.

Kersten Geers, “Architecture with Delay,” in architecten de vylder vinck taillieu 1 boek 2, Jan De Vylder, Inge Vinck, Jo Taillieu eds. (Ghent: MER Paper Kunsthalle), 49.

History/Theory is a collaboration between the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zürich and e-flux Architecture.

Category

Subject

History/Theory is a collaboration between the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta), ETH Zurich and e-flux Architecture.