In the days when the mail arrived in an envelope—franked by a stamp, delivered by a postman, and slid under the door—there used to be pen pals. This was a friendship of strangers, for strangers, by strangers. The more distant, the stranger the proximity.

Friendship creates a rupture. It disturbs the expectations of who can or should or must relate to whom. It represents the disobedient urge in human beings to stray from the familiar, the familial, the filial, the affinal. All friends are strangers, to begin.

Strangers who discover friendship in the interstices of the postal system are saboteurs. They put a spanner in the protocols of hostility and indifferences that rule the world. Even designated enemies who send messages in bottles addressed to agonist shores can end up being friends. Pen pals can always be comrades. They can never be siblings. And that is the point. All men and women need not be brothers and sisters.1

In the days when the mail arrived in an envelope, it took months, weeks, for the letter to get where it was intended to go. The two franking impressions—date and place of dispatch (Rio de Janeiro, Leningrad, Manchester, Nauru, Vancouver, Lagos, or Karachi) and date and place of reception (New Delhi General Post Office, sorting section, and then the neighborhood post office)—indicated an interval of time and a cascading parenthesis of transit (by air or ship or train and finally inside a satchel on the postman’s bicycle) across oceans, deserts, cities, ruins, backstreets. This represented one of humanity’s greatest achievements: the universal postal system.

An embrace across the world suspended between the writing and the reading of a letter, poised on a stamp. These correspondences were complex algebraic equations, with many brackets opening and closing in on themselves, as they moved across latitudes and longitudes, war zones and trading blocs, from pen pal to pen pal.

Usually, these commitments in fountain ink and biro held no expectation of meeting. Pen pal-ship might wilt if pen pals came across each other. The point was knowing that even if a correspondent never crossed the threshold of their addressee’s house, they would always be present in a drawer, or a shoebox, or wherever it was that letters, postcards, bus tickets, or the other paper ephemera that made up a life of hits and misses, were kept safe, for amnesia, or for posterity. They would glow in the dark with the luminosity of a friendship that placed no conditions, set no terms, asked for nothing but a reply, in some time.

Green ink. Purple ink. Ink that was fading. Chain letters that said that they were magical charms. Alphabets smudged by tea stains or tears. Spelling mistakes, the awkwardness of a foreign language that was hard to speak, harder to write.

The occasional photograph. “This is me, I’m 12 years old, I have a red bicycle.” “My father plays chess.” “My brother broke his arm.” “Do you have a favorite ice cream flavor?” “I would like to visit your country and learn your language and climb your mountains.” “We do not have very high mountains in our country, but we have a volcano. It is our ancestor. Here is a picture.”

The picture in the picture postcard—the grandfather volcano, smoking, but benign. And then other pictures in other postcards—animals, landscapes, portraits, city scenes, paintings in museums.

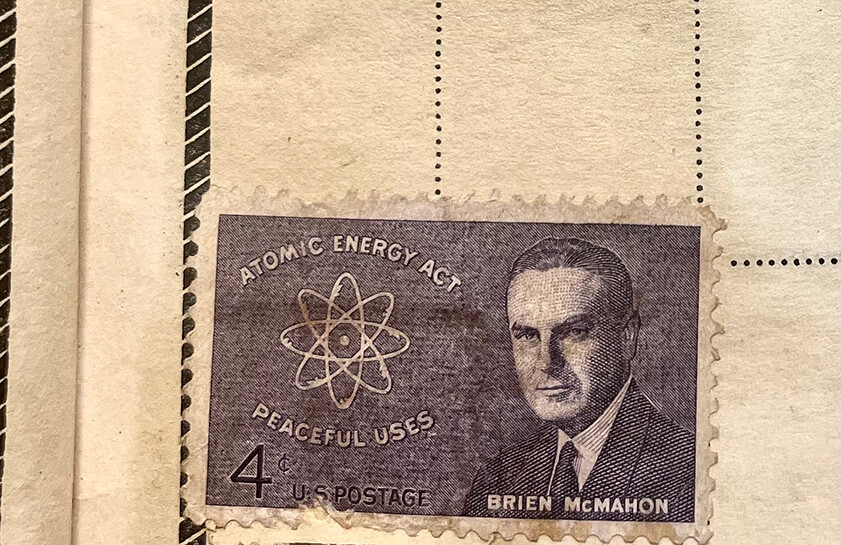

The images in the postage stamps: birds, great men, women, the heads of indifferent monarchs, the tales of bygone times, flora, fauna, folk dances, colorful costumes, cauliflowers and other produce, foraging sheep, lactating cows, ruminating rhinos, coal mines, oilfields, monuments, machines, musicians, mothers, marginalia, vaccinations, veterans, veterinarians, happy children, heroic happy workers, stars (cinematic and astronomical), soldiers, tanks, trucks, tractors, rockets, mountains. Always mountains. And sometimes, a whiff of a distant mushroom cloud.

There is an Indian postage stamp, issued in 1988, of the Nanda Devi mountain. Hidden in the design, inside the image of its snow mantle, there has to be, at least notionally, a “listening” device presumed lost in 1965. That’s a communication device—a stamp—with a communication instrument—a plutonium-battery-powered transponder—hidden in the picture on the stamp of the snowdrifts of the mountain, eavesdropping from on high, on distant nuclear explosions in the place where the Taklamakan desert meets the Chinese-controlled rise of the Tibetan plateau. This stamp is a small, serrated rectangle of paper with an adhesive underside. It carries within it a labyrinth of messages and coded, radioactive histories.

Atoms for Peace stamp. Image courtesy of Mandip Singh Soin/Himali Singh Soin.

Many countries issue stamps with billowing mushroom clouds to mark the atomic bomb explosions in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As if they stood in as iconic markers of the twentieth century. Something we can all share as tiny totems.

Particularly enthusiastic mushroom cloud postage stamp publishers are the island nations of the South Pacific—such as the Marshall Islands, who commemorate not just the 1945 nuclear attacks but also the numerous atomic bomb tests, such as the twenty-three nuclear explosions that took place between 1946 and 1953 on the Bikini Atoll, in the Marshall Islands. The inhabitants of Bikini, whose explosive reputation was mined in the naming of revealing swimwear, were relocated so that the tests could be conducted, as they were told, “for the good of mankind.”

Pakistan has a 1999 five-rupee postage stamp commemorating its (and, perversely, India’s) nuclear weapons tests of that year. India makes do with pensive portraits of atomic scientists and scenic views of nuclear reactors.

These “atomic” stamps have been meticulously cataloged by a philatelist, ex-Royal Air Force (ballooning unit) officer, clergyman, and nuclear test veteran, the Reverend John Walden in a self-published “documentary book” titled The Nuclear Option: A Philatelic Catalog and Reference Book on Atomic Stamps. Turning the pages of Reverend Walden’s book is a lesson in humanity’s obsession with nuclear explosions—as if they were messages in atmospheric bottles from the twentieth century to the future, containing warnings and caveats about Homo sapiens’ newfound capacity for auto-destruction. Each “atomic” postage stamp is a mobile message of nuclear toxicity, working its way around the globe.

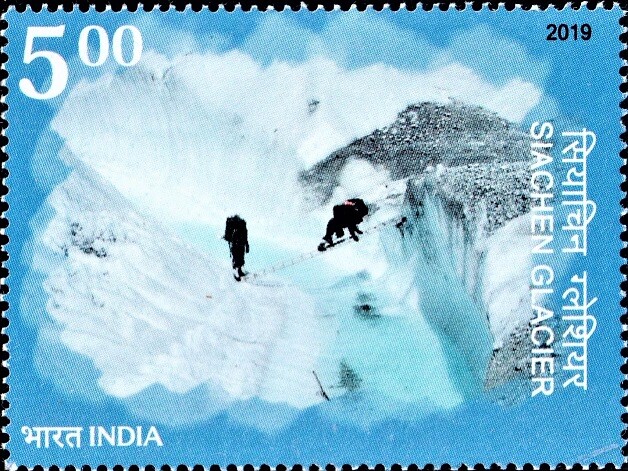

There’s another Indian postage stamp, issued in 2005, of the Siachen Glacier, in the Eastern Karakorum range of the Himalayas. This slow river of ice, currently under Indian control but claimed by Pakistan, is the highest battlefield in the world. In Siachen, sniper fire and gangrene due to frostbite compete as killers. Hostilities never cease. Ceasefires barely hold. But letters reach home, even from Siachen.

A postage stamp carries the imprint (literally) of the power that guarantees its passage and transmission. Nowadays, usually (though not always) that power is a state. A state is an entity that can collect taxes, maintain a standing army, build roads and some schools, put people in prison, and issue postage stamps. Which is why, sometimes, the smallest and least significant of states has the grandest and most beautiful of postage stamps, as if they were overcompensating for the ammunition in their arsenals with the reach (and elegance) of their postage services. On a postage stamp, even a mountain can be a battlefield, a site of victory or defeat.

Siachen Glacier. Source: iStampGallery.

Controlling a glacier or a mountain range with an army is making geological time a subject of geopolitical time. It takes a few million years for a mountain range to form, and for a glacier to take shape. Nation-states, on the other hand, form and dissolve in decades. Under the ecological impact of a social formation that puts armies on mountains and maintains nation-states, glaciers can begin melting in seconds.

The result: flash floods.

Flash floods are called this way for a reason. Videos of the recent flash floods in Pakistan register the incomprehension and the horror in the faces of those who saw their lives wash away in an instant. The geological timescale of a mountain, the temporal compression of a nation-state, and the dissolution of a glacier—these three ways of counting time have been caught in a moment of intersection.

Pakistan has the highest number of glaciers in the world, and even though only some are militarized, they are all susceptible to the consequences of another kind of conflict—the ceasefire violations between the weather and human beings in the now continuous attrition of climate change. The floods in Pakistan are read as a premonition of the actual consequences of global warming. A society that is responsible for less than one percent of global greenhouse gas emissions is still acutely vulnerable, because of its location and terrain, to extreme weather events; as if its people were being punished for consequences they did not cause. Who can configure this unjust algebra?

No state has the capacity to understand the consequences of the planetary transformations that are underway. Mountains, glaciers, skies, and rivers run on one kind of time. Borders and border patrols run on another kind of time. The countdown to a missile launch and the inching inclination of a glacier represent two different temporal orders. When the recently fenced-in communities called nation-states begin trying to alter the time of mountain, sky, and glacier, they embody the logic of the assault of one order of time on another. They may not succeed, but even their failures will have floods.

When a glacier cracks, the slow progress of snow over inches turns into the sudden inundation of ice-melt at the speed of hundreds of kilometers, in a matter of seconds. This force, this speed, this intensity of the experience of time, unties the knots of the discourse of bounded communities. Societies can come undone, swiftly.

What would a letter transported by a Nanda Devi stamp, or a Siachen Glacier stamp, or a South Pacific Mushroom Cloud stamp, from one pen pal to another, tell the world? What would their epistolary disobediences consist of?

Dear Friend,

I don’t know how long it will take for my letter to reach you. The way things are going, I don’t even know what will happen in the next few days. The post is erratic. Still, I thought it better to send you a letter rather than an email. I know, you could aways print what I type and keep the paper in a file. But this letter carries with it the impress of my hand. The alphabets shake when I write because of the chill in my fingers (the heating, like the post, is also erratic … because, as you can imagine, things being the way they are, what with that war that changes shape, the pipelines are short of gas, and it’s very cold, outside and inside.)

I am sending you a picture postcard of my favorite mountain view. This year the storms have been severe, and so have the landslides. Sometimes the fog makes the mountain disappear. There’s actually a gash on the mountainside which is not there in the postcard. Wounded glaciers are sculptors. The mountain is in disguise. But the postcard gives you a good idea of what I look at from my window.

The gash in the mountainside is from a landslide. It is impossible to mend the mountain now. Now, we cannot but think of what unbinds soil, what unsettles rocks, what undoes morphology. There’s no letting go of the injured glacier and the landslide when you’re trying to cross the mountain. There must be another side. Do you remember something I had once written, “The care of life and the care of self are not possible without care with toxicity.” You can’t care without thinking about what causes you to care in the first place.

The world is strange. The mountain seems to laugh. And I must remind myself to water my bonsai orange tree. It has borne tiny fruit. They are very tart.

I hope you are well, regardless. Write, it makes me think you are not that far.

Yours, sincerely.

We grew up listening to the rhetoric of “all men are brothers and sisters” in seemingly endless speeches of the 1960s and 1970s.

Half-Life is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Art Institute of Chicago within the context of its exhibition “Static Range” by Himali Singh Soin.