Space is governed by a diverse, contingent, and often contradictory set of policies, practices, and physical artifacts that determine who gets to live or hang out, where and for how long. While access to parks, plazas, sidewalks, and other inland urban spaces is controlled through things like loitering ordinances, curfews, sidewalk management plans, busking bans, and uncomfortable furniture, the beach comes with its own set of exclusionary devices. The beach might be synonymous with fun and sun, and where millions escape to on hot, summer weekends, but don’t be fooled by this carefree, breezy edifice. The beach where you are building sandcastles, body surfing, and sunbathing is built on a battlefield.

The battle lines were drawn in 535 AD, when the Byzantine Emperor Justinian declared in his Institutes that:

By the law of nature these things are common to all mankind—the air, running water, the sea, and consequently the shores of the sea. No one, therefore, is forbidden to approach the seashore, provided that he respects habitations, monuments, and the buildings, which are not, like the sea, subject only to the law of nations.1

This “public trust doctrine” establishes rivers, oceans, and other bodies of water as a commons to be enjoyed by all citizens equally—for recreation, fishing, navigation, and commerce. Accordingly, jurisdictions that have adopted the public trust doctrine (which includes the United States) are responsible for maintaining their accessibility and preserving their ecological integrity. Public trust lands typically extend to the “mean high tide” mark, which is the average elevation water reaches at high tide. The lands beneath waterways cannot be bought and sold either, except under circumstances where the public stands to benefit from their privatization. Public and private landowners may own properties adjacent to or even slightly past the mean high tide line, but they may not keep the public from accessing it.

That doesn’t mean they won’t try, as any beachgoer who has encountered a “PRIVATE ACCESS: RESIDENTS ONLY” sign knows. Residents who assume—wrongly—that the right to the beach is theirs and theirs alone will go to great lengths to defend it against perceived outsiders. In 1995, Michael Moore’s short-lived newsmagazine television show TV Nation staged an experiment: what if, on a hot summer day, a busload of racially diverse New York City residents tried to access the “public” beaches of wealthy, white Greenwich, Connecticut? After an unsuccessful attempt to enter the beach from the parking lot, the group boards a tugboat and, a mile offshore, gets into dinghies to start paddling toward the idyllic coastline. Minutes later, the Greenwich police arrive and form a barricade, prompting the New Yorkers to jump in the water and swim to the beach, where they are booed, accused of ruining a holiday, and threatened with arrest. “If you like the lovely beach why don’t you buy some property in Greenwich, pay taxes, and come here and enjoy it,” exclaims one beachgoer. “I don’t see why we’re making a big fuss over this,” says another. “Just get ’em out. Have ’em arrested and throw ’em out.2

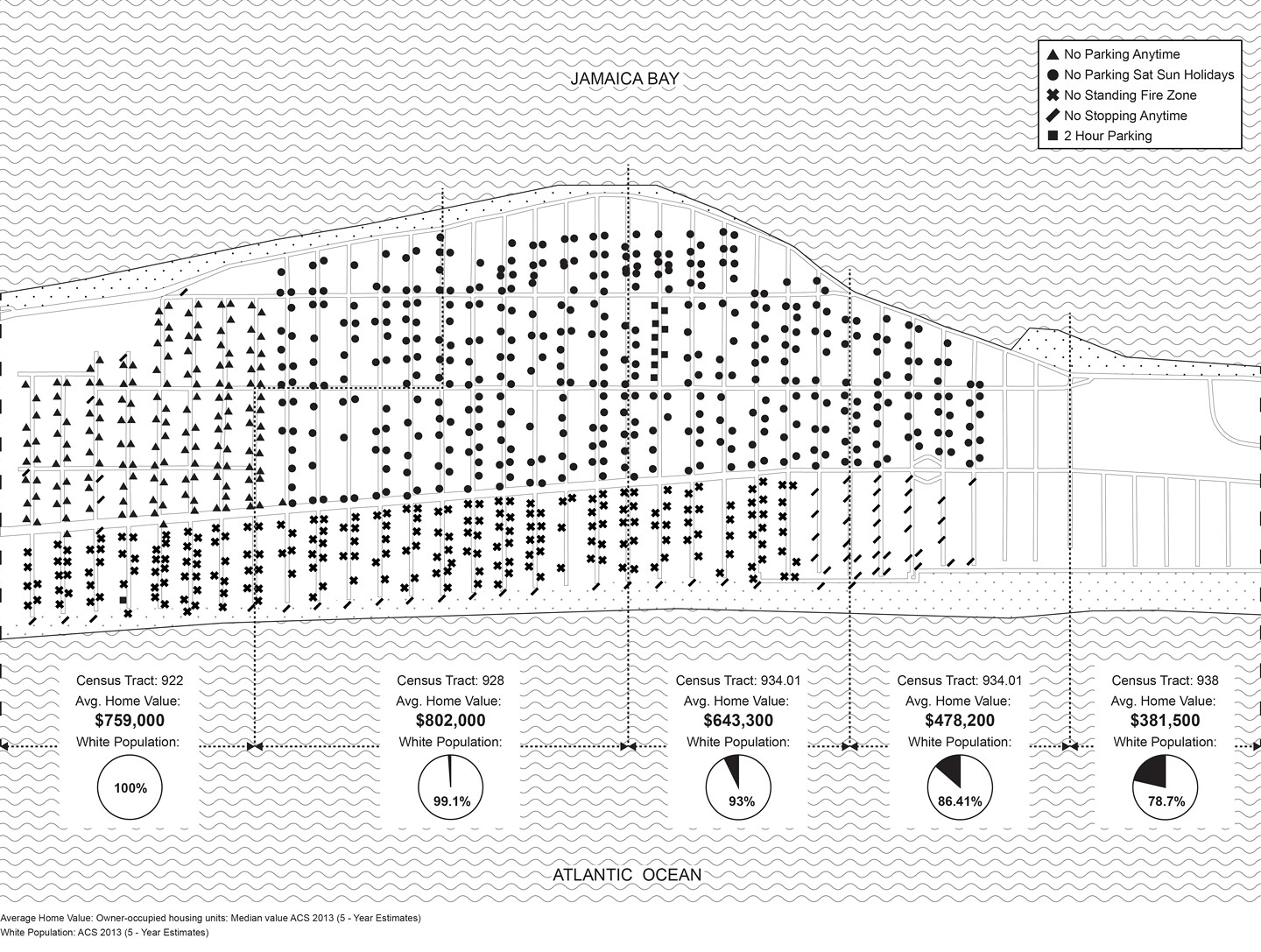

A map showing the location of restrictive parking signs in the Rockaways. As average home values and white population percentage decrease, so do the number of “No Parking” signs.

In the interest of not attracting the attention of beach access advocates, other actors use more subtle tactics to defend “their” beach. Beachfront communities in most cases do nothing illegal when they institute a “residential parking program” on their streets, don’t provide public parking, or pass on a bus or rail stop that might provide non-residents with beach access. Maximum one- and two-hour parking spots are another way to offer public parking without allowing them to be “gobbled up by beachgoers,” effectively preventing a nonresident from having his or her day at the beach.3 Or consider the “FIRE ZONE” signs that are so abundant on Queen’s Rockaway Peninsula. Belle Harbor and Neponsit—two of the whitest, most affluent neighborhoods on the peninsula—share a pristine strip of beach that has been owned and managed by New York City’s Department of Parks and Recreation since 1939.4 On most residential blocks, signs declare that street parking is banned from May 15 to September 30; on others, parking is prohibited during weekends and holidays.5 And on more than twenty blocks of dead-end streets abutting the beach, “NO STANDING: FIRE ZONE” signs forbid parking anywhere at any time. Transportation officials claim that if cars were allowed to park on the street, there would be no room for emergency vehicles like fire trucks to turn around.6 If this claim were true (it is not), then why are there no such parking restrictions the parallel streets in the poorer, less-white neighborhoods to the east? They too are dead-end streets that abut the beach and have roughly the same width as those in Belle Harbor and Neponsit.7 Interestingly, the city’s Department of Transportation website has no record of most of the “NO STANDING: FIRE ZONE” signs even existing.

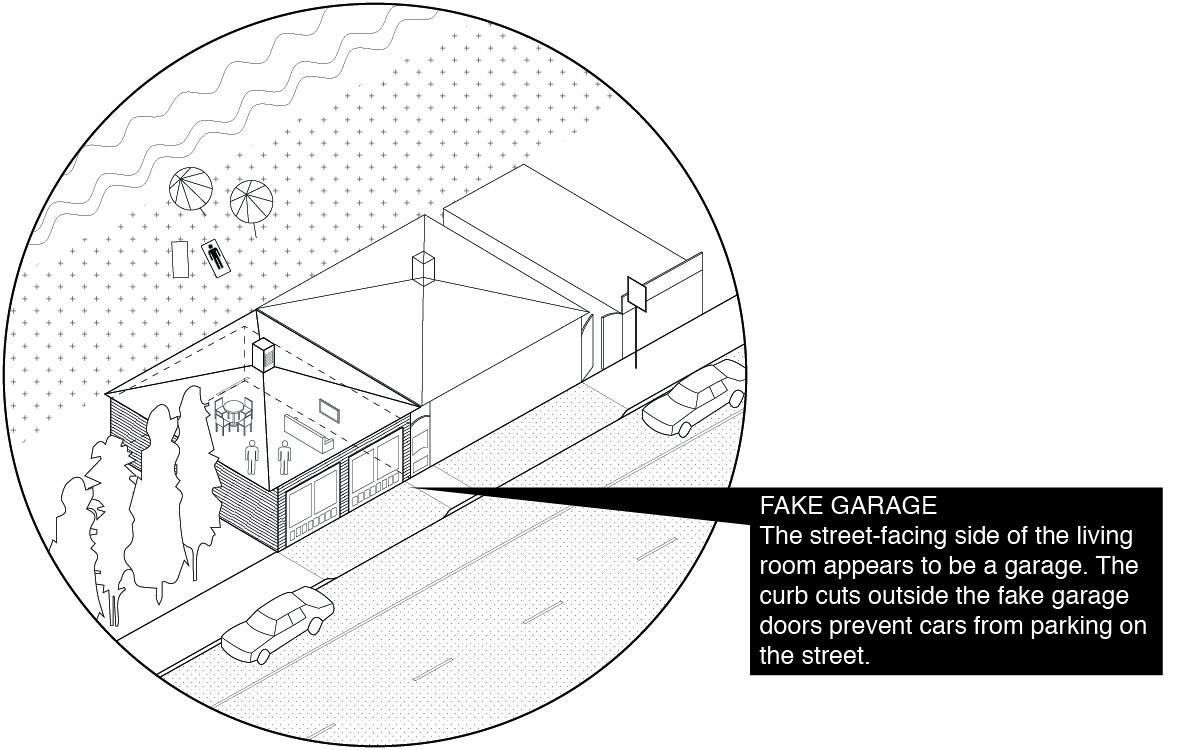

West-Coasters can play this game too. For those outside the one percent, accessing Malibu’s public beaches can feel a lot like breaking the law. Hundreds of fake “NO PARKING,” “NO TRESPASSING,” and “PRIVATE PROPERTY” signs litter the coastal strip. But fake signs are not the only decoys deployed by Malibu residents against the beachgoing masses. Media mogul David Geffen’s beachside mansion notoriously features a fake four-car garage with false garage doors but very real curb cuts that prevent beachgoers from parking near the discreet public access path located directly next to the celebrity’s home.8

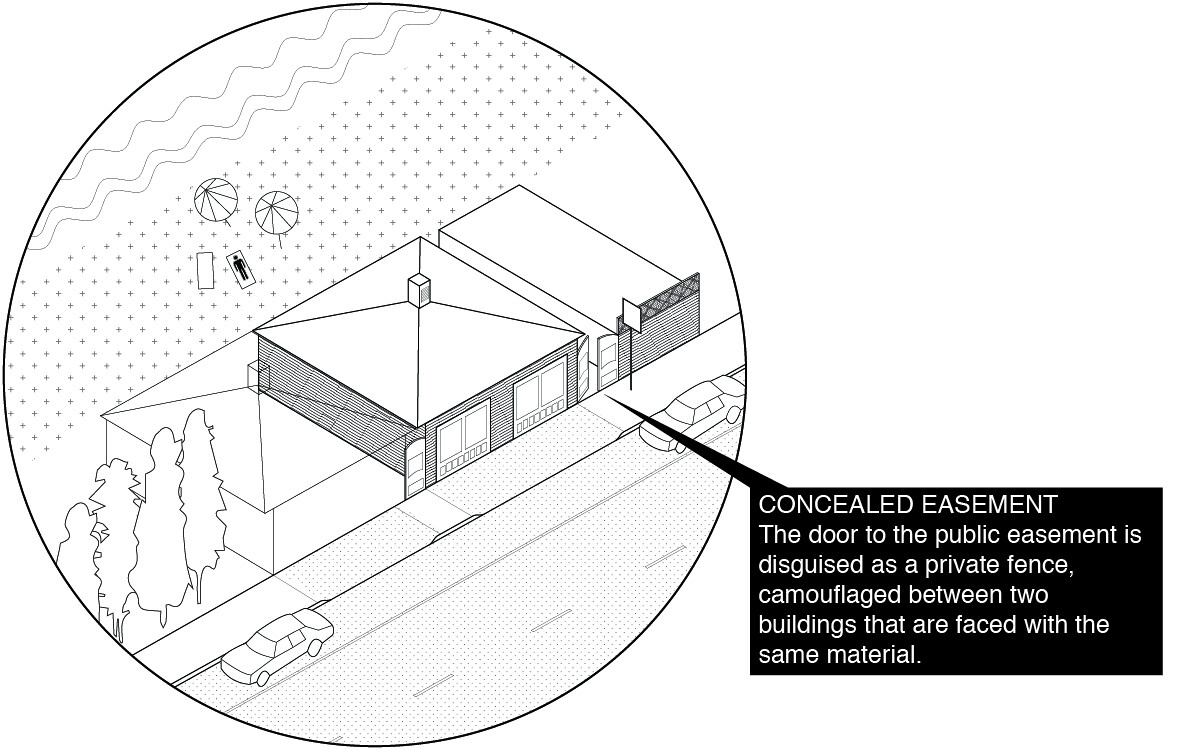

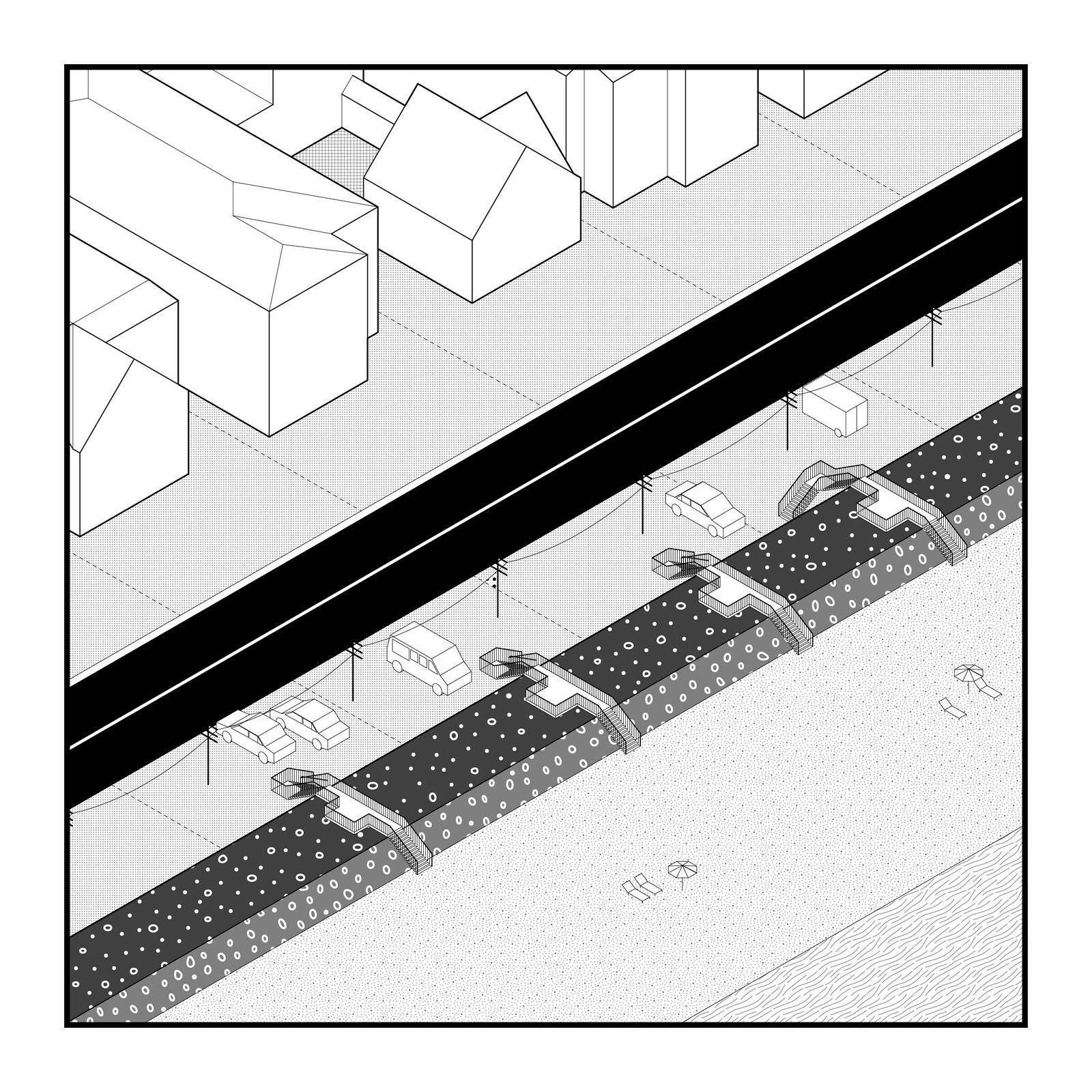

Concealed easements in Malibu, CA.

Fake garages in Malibu, CA.

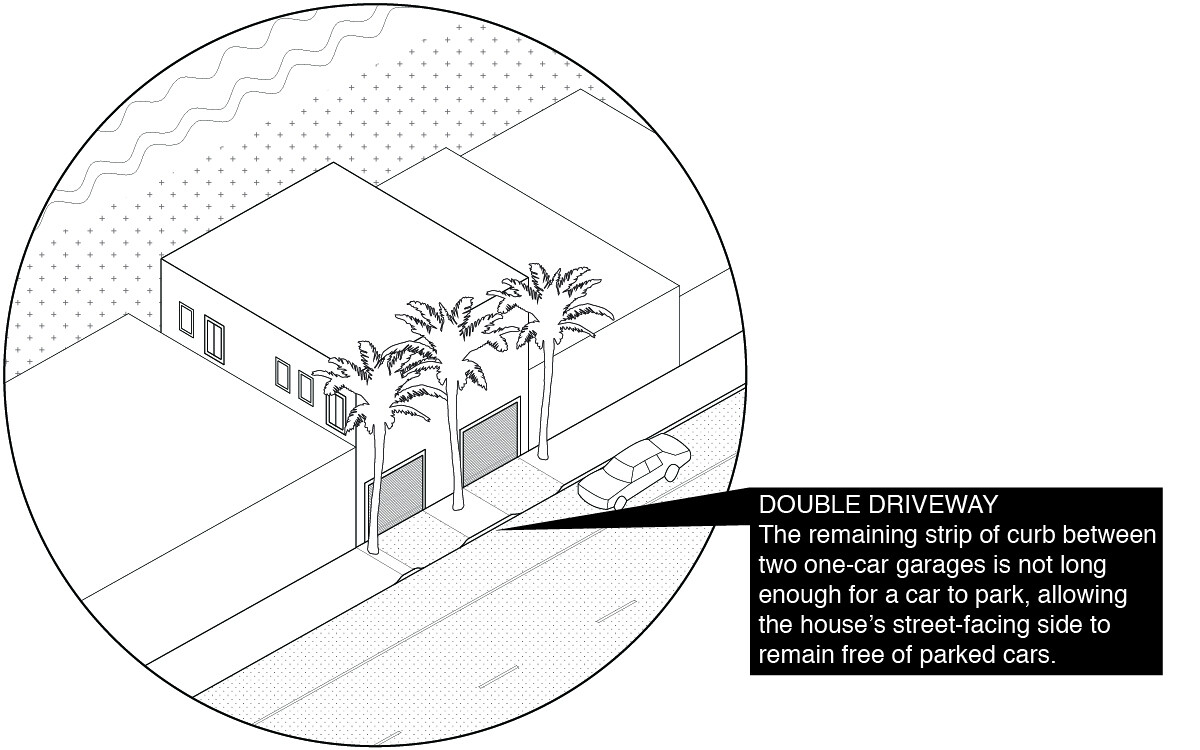

Double driveways in Malibu, CA.

Concealed easements in Malibu, CA.

Not all communities are so clever. Most don’t need to be. A much more tried and true weapon of beach exclusion is the beach badge, paid permits that provide access to beaches, swimming pools, and other recreational amenities to residents and their guests, dues-paying club members, or hotel and resort patrons. As historian Andrew Kahrl has written, while the use of beach badges was first adopted in the 1960s and 70s by wealthy and upper-middle-class suburbs in the densely populated northeastern corridor stretching from New Jersey to Connecticut, their use has since become commonplace.9 Kahrl notes that legal challenges invoking the public trust doctrine—many of them inspired by the open beaches movement that spread across the US in the 1960s—largely failed, losing out to the argument that “the cost of maintenance and staffing warrants their use and that without restrictive access policies, beaches would become overcrowded and, as a result, suffer environmental damage.”10 In the 1972 decision The Borough of Neptune City v. The Borough of Avon-by-the-Sea, the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that municipalities may charge fees to access public beaches so long as they don’t discriminate between residents and nonresidents.

Some communities have garnered a reputation for their sand shenanigans. Sea Bright—a thin sliver of a barrier island in New Jersey—is one such place. “Private” beach clubs routinely post phony “PRIVATE PROPERTY” signs and hire security guards to shoo and intimidate people away from public beaches. But more egregious is the town’s history of shirking state and federal mandates to provide beach access in exchange for aid. A 2006 state complaint pointed out that the Borough of Sea Bright had not paid for any of its portion of federal- and state-funded beach replenishment work that was completed in 2003, had backed out of its agreement to operate a public beach on state-owned land, and had neglected repairs at municipal parking lots promised in exchange for public beach aid.11 In the same complaint, the Attorney General accused nine private Sea Bright beach clubs of barring the public from adjacent beaches while profiting from years of publicly-funded beach replenishment and improvement efforts. (The replenishment has cost taxpayers $29 million to date.) The state’s lawsuit, filed in amicus with the American Littoral Society and Citizen’s Right to Access Beaches (CRAB), led to settlements with the Borough of Sea Bright and six private beach clubs who agreed to contribute money into the state-managed Sea Bright Public Access Fund to finance public access improvement projects.12

In recent years, Sea Bright’s private beach clubs and residential developments have begrudgingly provided public access points, but many are so far from where visitors can park that they are more or less useless to anyone arriving by car (some determined beach visitors now hitch bicycles onto their cars so that they can ride to the beach from their distant parking spots).13 After Superstorm Sandy, Sea Bright proposed purchasing the wrecked Anchorage Apartments to convert the site into additional public parking for beachgoers,14 but after staunch opposition from residents, the site was instead converted to a public “passive park”: an empty yard, completely enclosed by a fence, utterly devoid of parking—and, for the most part, the public.15 And when the town repaired a portion of the seawall that was breached by Sandy, it downright neglected to include any parking spots or walkovers whatsoever, even though the site was formerly publicly accessible.

A private walkover with deck in Sea Bright, NJ.

Many walkovers in Sea Bright now feature locking gates to prevent public access to the seawall.

This public beach access point in Sea Bright is hidden behind a utility building. The no parking sign and unpaved lot makes it difficult for visitors to access.

A “no trespassing” sign discourages visitors from reaching a Sea Bright public beach access point beyond.

Signs and barriers at this Sea Bright walkover send a clear message: public stay out!

A private walkover with deck in Sea Bright, NJ.

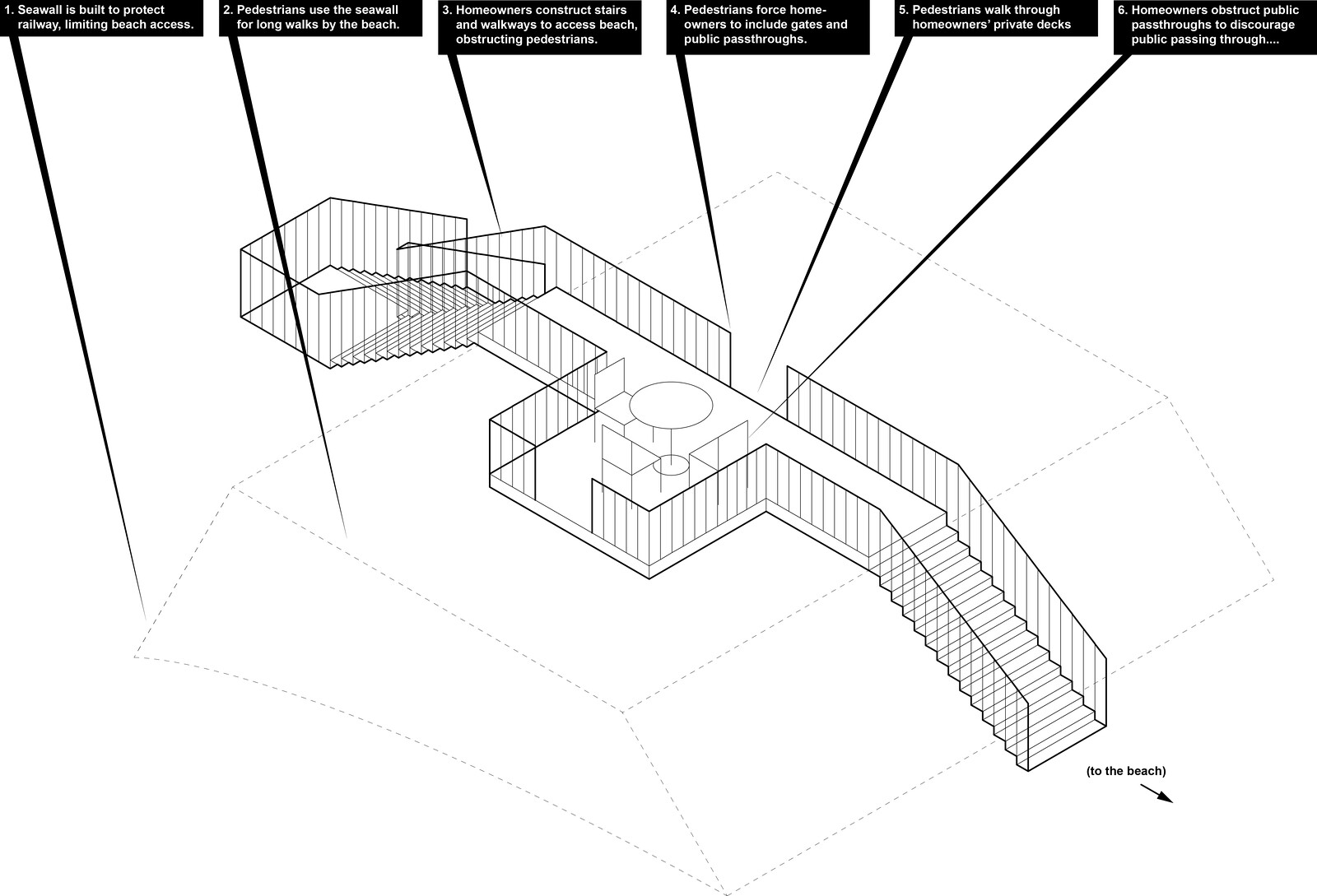

Sea Bright’s homeowners can be just as cunning. Sea Bright’s twenty-home Tradewinds development was approved in 2004 on the grounds that it would offer beach access and on-street parking for beachgoers. There is indeed free parking on one side of Tradewinds Lane (the other side is a fire lane), but Tradewinds residents fill these public spots with their own cars, instead of parking in their own driveways and garages—effectively ensuring that the public spots won’t be used by beachgoers.16 And then there is Sea Bright’s “walkover” saga. Further up the beach, many homeowners have taken to constructing walkovers: private, wooden staircases that allow people to traverse the seawall that separates Sea Bright from the beach. At the top of most walkovers, one can find fenced-in decks that allow the homeowners to take advantage of the ocean view that the top of the sea wall affords. A lawsuit led by the Littoral Society on behalf of people who walk along the seawall (which functions as a sort of public promenade) resulted in a compromise: homeowners who built walkovers with decks would be required to include gates that enable wall walkers to pass through. The story could have ended there but didn’t: in recent years homeowners have started building labyrinthine walkovers that obscure the seawall path, creating something of an obstacle course. The result is a rather curious artifact: a sort of Rosetta Stone whose markings reveal a series of conflicting attitudes—and analogous rules and regulations—about who has the right to be where, when, and for how long.

Beach battles in places like Sea Bright often boil down to the question: does the community’s need for safety and climate resiliency outweigh its desire for exclusive, quasi-private beaches? Some wealthier communities like to think that they have the luxury to reject aid outright, preferring to invest private dollars in replenishment and resiliency projects rather than open their shores to the huddled masses. Mantoloking, a seaside haven for millionaires fifty miles north of Atlantic City, has a long history of resisting publicly-funded beach replenishment projects, citing increased access requirements that would come with the replenishment as a cause. Even after Sandy devastated the barrier island—every one of Mantoloking’s 520 homes sustained water damage and several were swept out to sea—homeowners still resisted any aid that would require increased public beach access.17 A 2012 “Beach Replenishment Fact Sheet” distributed by the Borough of Mantoloking attempted to reassure homeowners that restoring the beach would not mean more public access, ending in all caps:

IT IS IMPORTANT TO NOTE THAT THE BOROUGH’S PROPOSED PLAN DOES NOT INCLUDE ANY ADDITIONAL RESTROOM FACILITIES … OUR PLAN IS FOR BEACH ACCESS TO REMAIN THE SAME—IF THE PUBLIC WANTS TO CONTINUE TO USE THE BEACH, THEY WILL HAVE TO USE PUBLIC ACCESS POINTS WITH THE REQUIRED BEACH BADGE.18

In 2013, the Borough resorted to threats of using eminent domain to seize oceanfront parcels from holdouts blocking recovery and replenishment efforts, but to little avail: three years later, the Borough Council was still mailing letters begging holdouts to grant the necessary easements and allow recovery work to begin.19 A letter in February 2016 promised homeowners that the general public would remain “quite a distance from your home,” separated by “a massive dune” that would be kept “free of beach-goers” by the police.20 This summer, five years after Sandy, relief projects are finally slated to begin in Mantoloking as part of a $128 million replenishment effort for Ocean County, NJ.21 And more good news for would-be beachgoers: the borough also plans to lift its famously strict two-hour beach parking restrictions.22 But rest assured, the battle of the beach continues to rage—the neighboring communities of Bay Head, Point Pleasant Beach, and Berkeley Township soldier on, still resisting recovery projects and the beach access stipulations that come with them.23

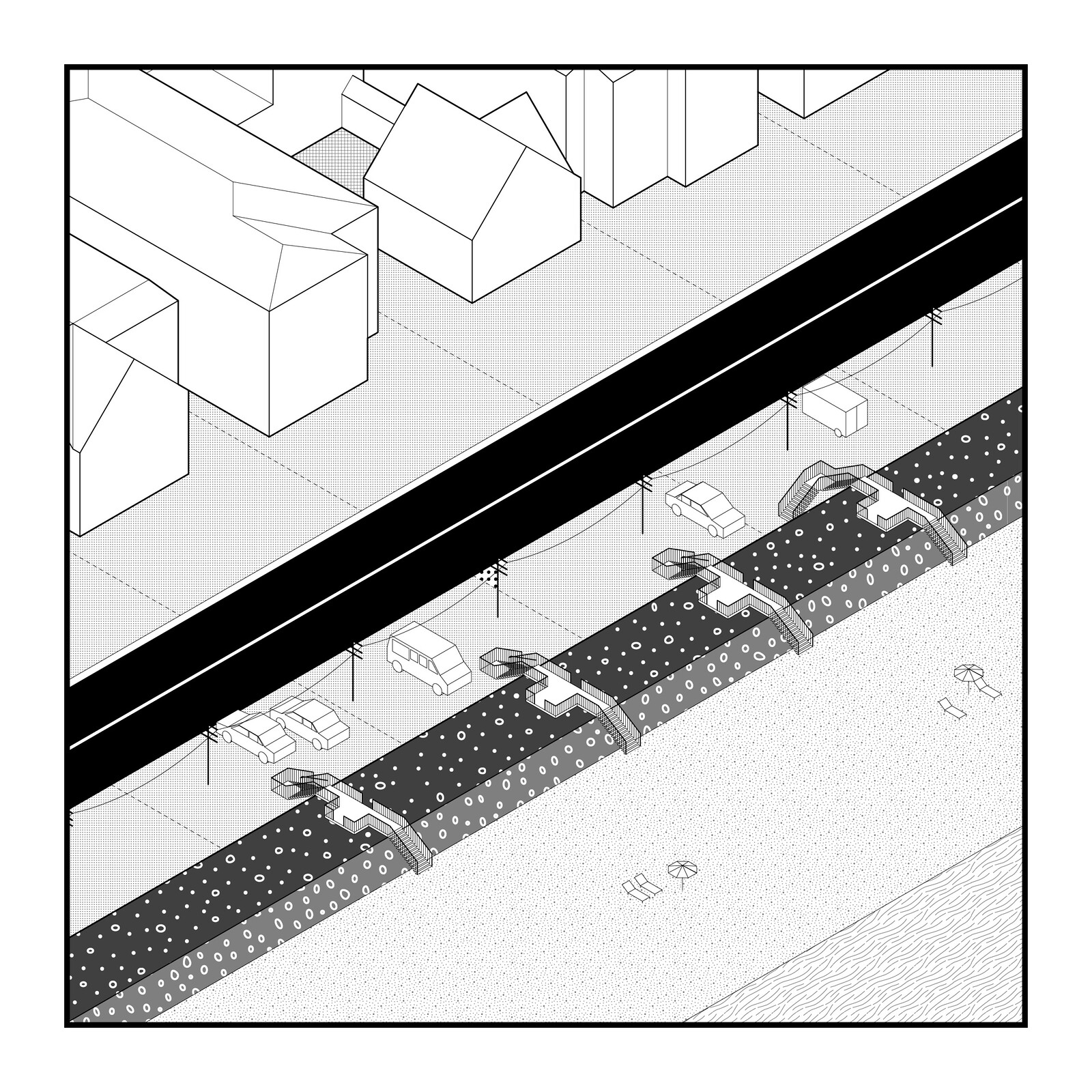

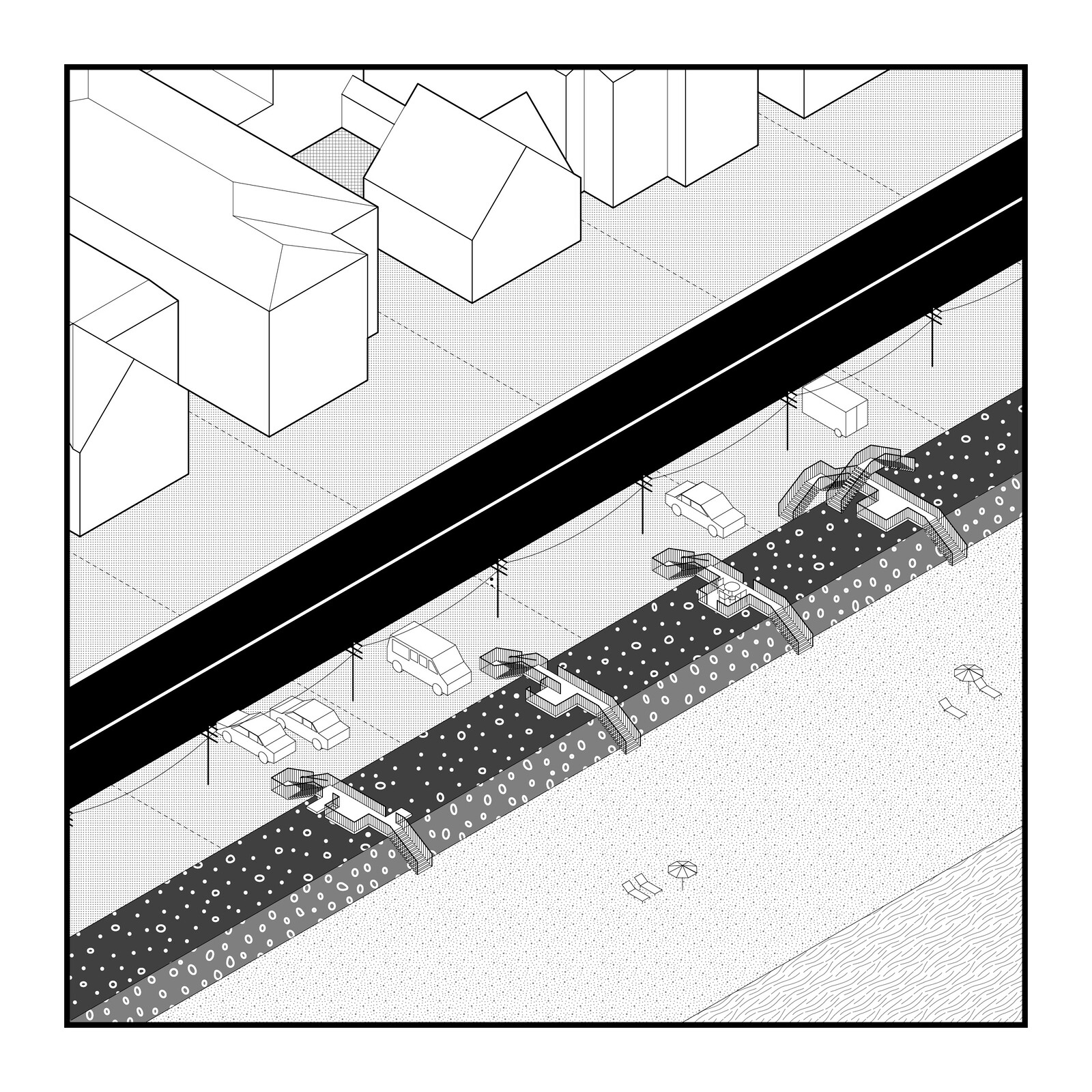

1890: The New Jersey Southern Railroad runs along the Jersey Shore, passing through Sea Bright. A continuous sea wall is built in the following decades to shelter the railroad from storms and erosion.

1990: The railroad is long gone, and houses line the former route. Homeowners have taken over the rail right-of-way, using it for private parking and storage. Some have extended their claims all the way to the water, building wooden “walkovers” to easily reach the beach from their homes. People who used to enjoy strolling along the top of the seawall are not pleased to find their path obstructed.

2013: Sea Bright has been rebuilding following Superstorm Sandy. Most homeowners have started building deluxe walkovers that include private decks. Walking along the sea wall is now completely impossible. Wall-walkers are furious. Can this be legal?

2016: Following lawsuits, Sea Bright homeowners are ultimately allowed to keep their walkovers and decks. However, there is a compromise. Private walkovers must include gateways that allow the public to pass through freely. A truce—for now… but what stormy seas lie ahead?

Today: Creative homeowners can still find ways to kick sand in the faces of the sea-wall-walking public, while still obeying the new law. They have built the required passthroughs, but they don’t have to keep them clear. Misaligned passthroughs force a meandering walking path, gateways slow down pedestrians’ progress, and impeding deck furniture makes it clear that pedestrians are crossing through private property.

Anatomy of a Sea Bright walkover: a peculiar artifact of the battle for the beach.

1890: The New Jersey Southern Railroad runs along the Jersey Shore, passing through Sea Bright. A continuous sea wall is built in the following decades to shelter the railroad from storms and erosion.

It’s crucial to remember that, thanks to the effects of climate change, places like Belle Harbor, Neponsit, Malibu, Sea Bright, and Mantoloking will soon be uninhabitable. They may be able to hold back waves of beachgoers, but they won’t be able to hold back the sea. Why not get a head start and convert these precarious enclaves from beach resorts for those who can afford them into beaches for everyone? As the urbanist David Rusk puts it, “For any responsible citizens or any responsible public officials who are not slaves to their own four-year re-election cycle, the rational long-term policy must be to gradually phase out permanent, man-made structures on the barrier islands and convert them into state and national parks.”24 He continues: “Decade-by-decade, the barrier islands must shift from being based on fixed, permanent, hard infrastructure (houses, stores, offices, etc.) to being based on removable, temporary, soft infrastructure (marinas, houseboats, trailers, tents, food trucks, etc.) to, in a century’s time, a chain of state and national parks and wildlife refuges where there is no permanent human presence.”25

In fact, an excellent precedent for this sort of environment can be found just ten miles south of Mantoloking. Occupying the southern half of the Barnegat Peninsula is Island Beach State Park, one of the largest barrier reserves in the US. Maintained by the New Jersey Division of Parks and Forestry, the park gives beachgoers a taste of what all of New Jersey’s coast could have looked like with more enlightened land management: a pristine, white sand beach flanked by robust dunes, a healthy, functioning tidal marsh, and a maritime forest, all serviced by a two-lane access road and parking lots and bathrooms spaced at regular intervals. Because there are no residents, it’s a territory free of phony no-trespassing signs, fake garages, and other resident-inspired shenanigans.

Actually, there is one resident. Soon after purchasing the land that would become the park in 1953, the State of New Jersey established the house that had occupied the 2,694-acre estate as a vacation residence for the state’s governor. In the summer of 2017, during the long July 4th weekend, Governor Chris Christie and his family were photographed on the (very empty) beach in front of the residence. Reclining awkwardly in a folding beach chair and sporting sandals and a black baseball cap, Christie was oblivious to the uproar that was soon to follow (and to the #beachgate hashtag, which trended heavily in the days to come). Owing to a government shutdown triggered by an unresolved state budget, the park entrance was closed that day, rendering the beach inaccessible to everyone except the Governor and his family (a fact that is well-evidenced by the acres of empty sand that surrounded the Christie encampment). The symbolism made for a memorable meme: an unpopular politician enjoying his day at the beach while the public is deprived of theirs thanks to said politician’s perceived incompetency. The internet ate it up. Political opponents, too, saw raw meat. As we write, two bills are being debated by the New Jersey Senate: one that forces the governor’s beach house to close during a shutdown and another that would keep state parks open during a shutdown. Christie, however, saw no problem. “Let’s be really clear. That’s our residence and we have a right to be there whenever we want to be there” he told reporters. “The governor has a residence at Island Beach; others don’t … Run for governor and then you can have the residence.”26 As if getting to the beach wasn’t difficult enough.

In this context, one has to wonder: what good are accessibility measures in the face of the remarkable tenacity of the exclusionary impulse? Where there is a will to keep the public from the beach, people will find a way. Rising seas and more powerful storms will make establishing permanent homes and private communities on barrier islands increasingly expensive, risky, and impractical. Private owners of all those seaside habitations, monuments, buildings, and cottages may never retreat out of respect for the public good, but after enough Atlantic dousings, they may choose to abandon their cottages and head for the high ground. Enter Justinian again: “Accordingly, it is true to say that anything which is seized on, when abandoned by its owners, becomes the property of the person who takes possession of it. And anything is considered as abandoned which its owner has thrown away with a wish no longer to have it as a part of his property, as it therefore immediately ceases to belong to him.”

Dotty E. LeMieux, “The Public Trust Doctrine: Venerable and Besieged,” On the Commons (October 19, 2005), ➝.

”Michael Moore, “We’re #1,” TV Nation Season 2, episode 1, Fox Broadcasting Company (July 21, 1995).

Gregory Beyer, “A Beach Shared by a Tight-Knit Clan,” The New York Times (September 4, 2009), ➝.

Norimitsu Onishi, “Parking Bans Keep Outsiders from Queens Sand and Surf,” The New York Times (August 4, 1996), ➝.

Elizabeth A. Harris, “Rockaways Parking Bans Please Residents but Irk Visitors,” The New York Times (September 3, 2012), ➝.

Harris, “Rockaway Parking Bans.”

Martha Groves, “Scouting Out Malibu Beaches? There’s an App for That,” Los Angeles Times (May 27, 2013), ➝.

Andrew W. Kahrl, “Beach Tag” in The Arsenal of Exclusion and Inclusion, ed. Tobias Armborst, Daniel D’Oca, Georgeen Theodore, and Riley Gold (New York: Actar Publishers, 2017), 54–48.

Kahrl, “Beach Tag.”

New Jersey Office of The Attorney General, “State Complaint Seeks to Make ‘Private’ Beaches in Sea Bright Available to General Public,” (September 22, 2006), ➝.

New Jersey Office of The Attorney General, “Acting Attorney General, DEP Announce Settlement of Beach Access Suit with Six Private Beach Clubs in Sea Bright,” (January 13, 2010), ➝.

Pim Van Hemmen (Assistant Director, American Littoral Society), interview by Andrew Wald, August 7, 2017.

MaryAnn Spoto, “State eyes Sandy-ravaged Sea Bright condominium complex for beach parking,” NJ.com (June 11, 2013), ➝.

MaryAnn Spoto, “Sandy-ravaged condo property sold for $3M to become Sea Bright park,” NJ.com (March 9, 2015), ➝.

Bonnie J. McCay, Debbie Mans, Satsuki Takahashi, and Sheri Seminski, “Public Access and Waterfront Development in New Jersey: From the Arthur Kill to the Shrewsbury River” (Keyport, NJ: NY NJ Baykeeper, 2005), ➝.

MaryAnn Spoto, “Residents of Sandy-devastated Mantoloking finally heading home,” NJ.com (February 20, 2013), ➝.

Borough of Mantoloking, “Mantoloking Beach replenishment Fact Sheet” (December 2012), ➝.

Associated Press, “Mantoloking prepares to use eminent domain to turn homeowners’ property into dunes,” NJ.com (April 23, 2013), ➝.

Borough of Mantoloking, Chris Nelson to Homeowners of Mantoloking (February 16, 2016), ➝.

MaryAnn Spoto, “Long-awaited $128M Jersey Shore beach replenishment to start next month,” NJ.com (May 11, 2017), ➝.

Jean Mikle, “Mantoloking to ease parking restrictions for beach project,” app (June 19, 2017), ➝. See also Borough of Mantoloking, New Jersey, Borough Code, Chapter VII: Traffic.

MaryAnn Spoto, “Long-awaited $128M Jersey Shore beach replenishment to start next month.” NJ.com (May 11 2017), ➝.

David Rusk, “‘It’s Not Nice to Fool Mother Nature’: Beaches for Everyone through Managed Relocation on the Jersey Shore” Rebuild by Design (Unpublished, June 20, 2014).

Rusk, “‘It’s Not Nice to Fool Mother Nature’”.

Ryan Hutchins, “Christie spent night with his family in shuttered Island Beach State Park,” Politico, July 2, 2017, ➝.

Future Public is a collaboration between the New Museum’s IdeasCity initiative and e-flux Architecture for IdeasCity New York, 2017.

The Shore Wars project team is Tobias Armborst, Daniel D’Oca, Georgeen Theodore, Riley Gold, and Andrew Wald, with Jihwan Han, E. Talbot Schmidt, and Kathryn Sonnabend.

Future Public is a collaboration between the New Museum’s IdeasCity initiative and e-flux Architecture for IdeasCity New York, 2017.