The renovation of rural, abandoned villages does not need to entail a radical, metamorphic transformation of their functions and physical configuration. Rather, it can take place through a slow, continuous practice of inhabitation. Instead of planning and intervening, renovation can be conceived of as a restoration of relationships between a place and its dwellers. The techniques of such renovation practices include observation, listening, and, most importantly, staying. Staying with the place demands that we do not simply stay in the place—that we are not merely physically present somewhere—but that we stay in the sense of committing to and actively engaging in the dynamics of a place.

Since 2017, we have developed a series of spatial practices of staying in relation to the village of Topolò/Topolove, where we are based. We have taken space in the village, inhabiting different houses, occupying some others, transforming public and private spaces into commons, and building affinities with the inhabitants already living here. We have organized our everyday lives so that we are dependent on each other, sharing tools, spaces, knowledges, and infrastructures. We collectively practice care-taking of the village by considering its public space, its abandoned ruins, the ruderal landscape, and the spaces between as our (collective) house.

As an alternative to living in capitalist ruins, we might find ways of inhabiting and staying with capitalist leftovers, places that have morphological, architectural, and cultural qualities that were spared by processes of modernization.1 In the case of abandoned rural villages, staying means attempting to find modes of inserting oneself in a place’s already-established networks. Grounding ourselves in the village and its landscape, we formed a collective and “actively became in context,” a process that Jeanne van Heeswijk defines as a “balancing act between making emergent and re-rooting.”2 Key to this has been discovering historical, social, and physical facts about the place, which can provide entry points for reconfiguring its metaphysical connective tissue.

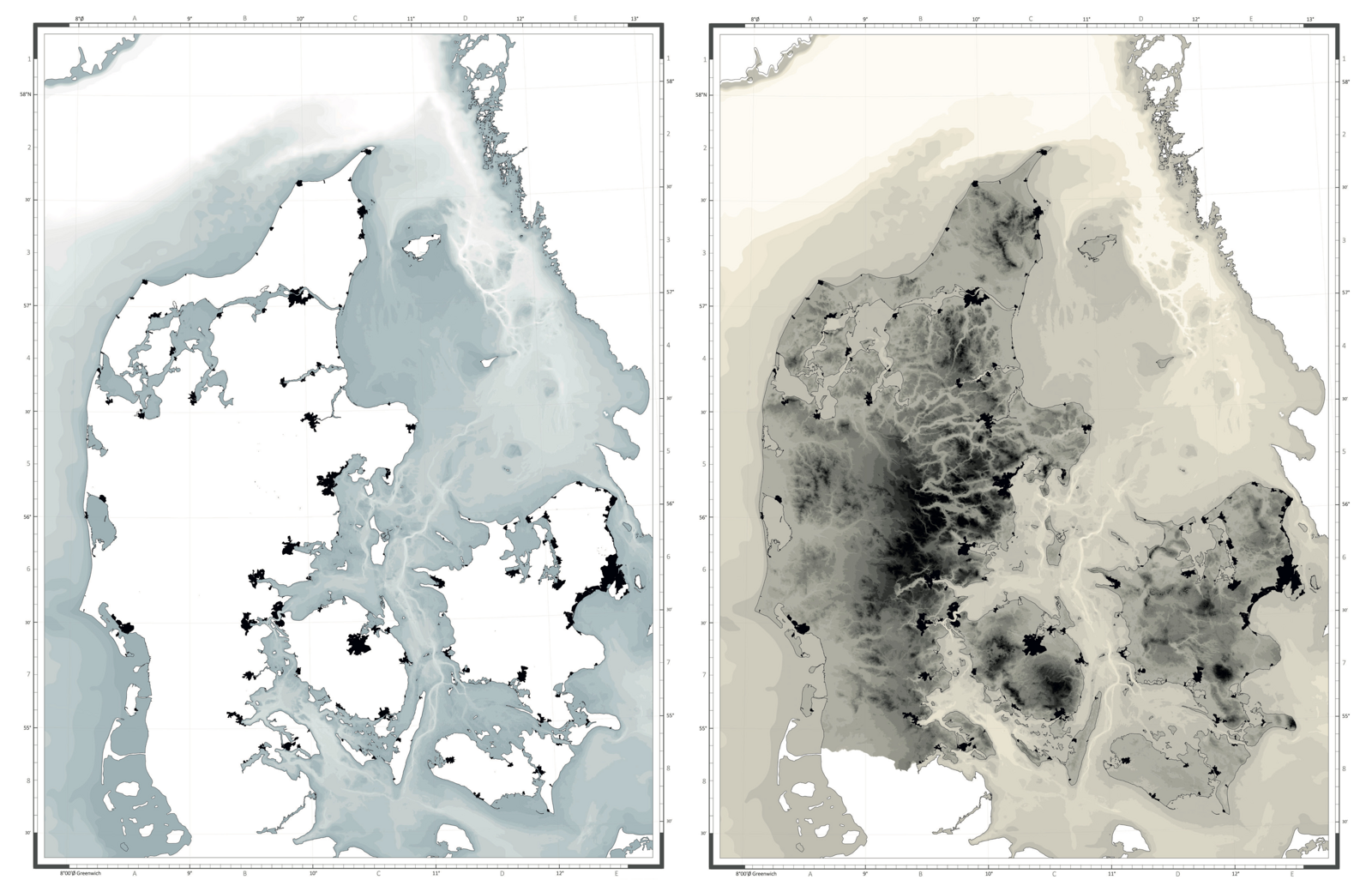

Map of Robida in Topolò/Topolove by Janja Šušnjar.

A Village on the Border

Topolò/Topolove is a village with twenty-five inhabitants located in the mountainous region of northeastern Italy, very close to the Slovenian border. Topolò/Topolove is in Valli del Natisone/Benečija, an area where ethnically-Slovene people have and continue to live, today as a linguistic minority.3 In the eighteenth century, Valli del Natisone/Benečija first passed from the hands of the Republic of Venice to the Habsburgs, and, in 1866, following the Venetian plebiscite, was annexed by the Kingdom of Italy. This area has been heavily impacted by geopolitical conflicts throughout the twentieth century. During the First and Second World Wars, for instance, it was the site of violent military operations, and the Slovene population was forcibly “Italianized” by the Fascist regime. Following the end of World War II, the borderland was transformed into a military zone. The area initially fell under the control of Gladio—the Italian clandestine “stay-behind” operation organized by the Western Union (the European military alliance established between France, the United Kingdom, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg)—and then by NATO (and the CIA), all in order to maintain control of the border between West and East. These turbulent events resulted in a significant decline in population, the erosion of the Slovene language and cultural identity, and the fragmentation of the community.

One of the primary political instruments that has since shaped the present-day reality of Topolò/Topolove has been the border, in both its physical and symbolic sense. In an attempt to maintain strict control over the so-called titini (Titoists) on the other side of that border, Italy— with the help of Gladio—tried to systematically force the people who lived in mountain villages in the border region to move out. They did this with the help of local spies, who kept note of what the local Slovene population spoke about. Other systematic measures were also undertaken, such as the deliberate construction of industrial complexes in the valleys, or the posting of financial police officers (Guardia di Finanza) who were tasked with preventing basic goods from being smuggled across the border. Planning regulations were also severely restricted. Inhabitants of the nearby village Lusevera/Bardo had to go to Padua (almost 200 kilometers away) to get permission to cut down trees in their own forests, as each tree apparently played an important role on the military playground. All of this can be understood as a proliferation of the border, which not only delimited the space between two countries, but also implanted itself into the space and life of the village. As a result, the people of this area became alienated from their environment, which only further inhibited the social, cultural, economic, and political activities of the Slovene community.

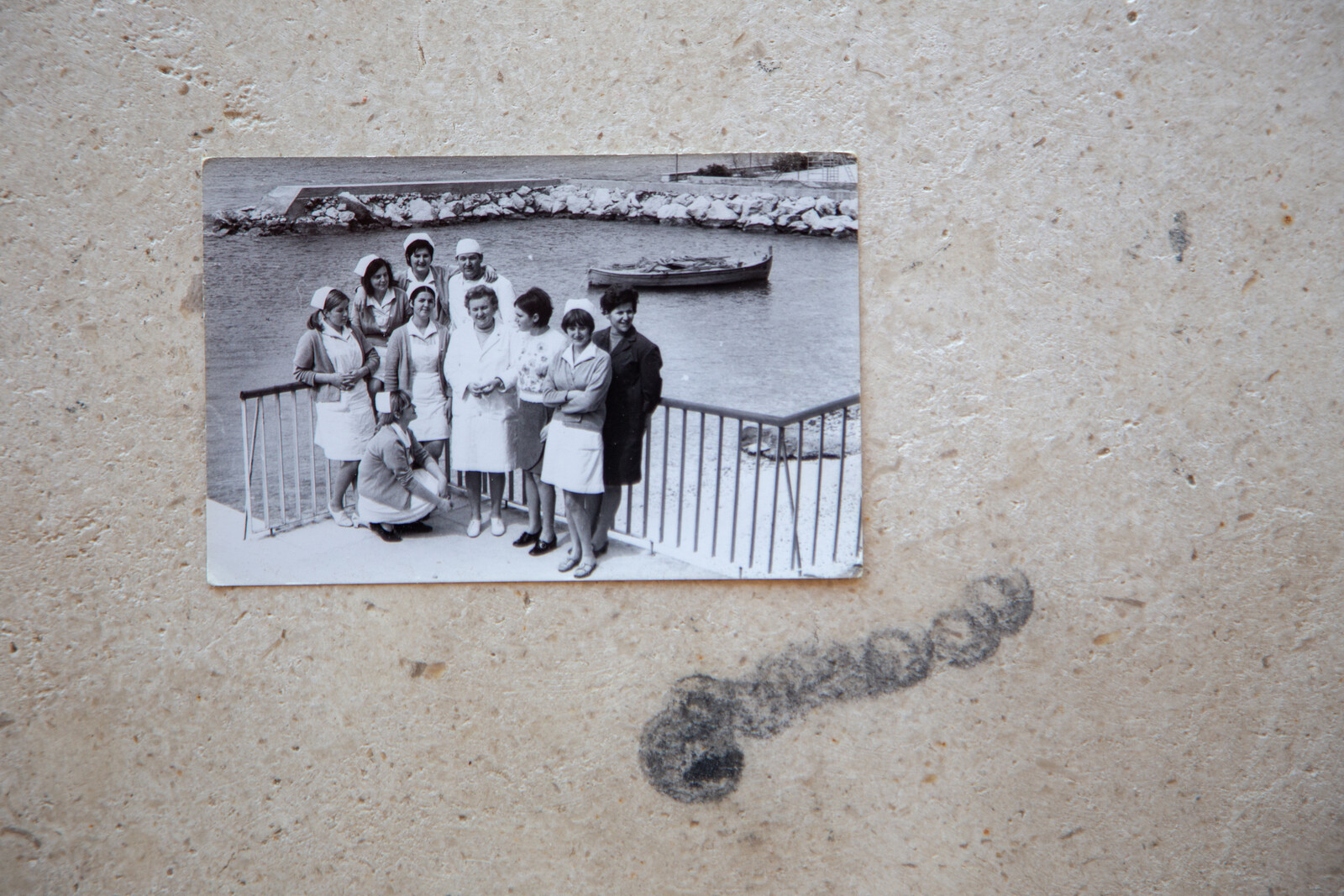

Scenes of life in Topolò/Topolove courtesy of Robida.

Scenes of life in Topolò/Topolove courtesy of Robida.

Scenes of life in Topolò/Topolove courtesy of Robida.

Scenes of life in Topolò/Topolove courtesy of Robida.

Scenes of life in Topolò/Topolove courtesy of Robida.

Scenes of life in Topolò/Topolove courtesy of Robida.

Scenes of life in Topolò/Topolove courtesy of Robida.

At the same time, these communities have long related to the concept of the border in ways other than division and separation, namely through its enabling of mixture and translation. With the neighboring villages on the other side of the hill—which not only demarcates two countries, but also two climates, one Mediterranean and the other Alpine—Topolò/Topolove has formed a kind of ecotone, the site of “a complex interplay of life forces where plant communities, and the creatures they support, intermingle in mosaics or change abruptly.”4 The area has long been a space of porous in-betweenness, where stable and fixed ethnic and national identities have been subverted as people from communities on both sides of the border share everyday activities such as grazing livestock in common fields, trading agricultural products, or falling in love and marrying.

In Topolò/Topolove, both aspects of the concept of the border—as division and as connection—have formed fertile ground for what Walter D. Mignolo calls “border thinking,” which entails “thinking from dichotomous concepts rather than ordering the world in dichotomies.”5 Renovating places that have been subject to the border therefore requires deconstructing their historically formed divisions and placing that which had formerly been alienated into radical proximity. “I am where I think,” Mignolo adds, so it is essential that these places are not holed up in themselves, in nostalgia or victimhood, but rather infused with urgent discourses and suffused with re-imagined dwelling practices.6 According to Jeanne van Heeswijk, the local is “not a specific place, but a condition that embodied global conflicts site-specifically.”7 As such, small, isolated, depopulated, and marginal villages can be sites for the development of reparative and imaginative spatial practices.

Village as House, Village as Ecology

Before moving there, Topolò/Topolove was a place that we—at the time a group of young people from the area and some friends—had all already developed a special affection for. As children, we would visit yearly and participate in the art festival Stazione di Topolò/Postaja Topolove. There, we met some important teachers and learned how a small, marginal village on a border could both become the center of contemporary art practices and be a place to meet the world.8 Through this collective yearly ritual of visiting the festival, we grew attached to the village, and we eventually began imagining ourselves moving there after our studies in different cities across Europe.9 When we finally began moving there in 2017, some of us only imagined it as a temporary solution—to avoid paying high rents in cities—and so decided to live in an empty house that already belonged to family. A few bought houses for very cheap, while others playfully imagined occupying an abandoned house, only to find a key to it in the family house that was just now being inhabited again.

At the very beginning, the houses in which we were living were humble. Some even lacked basic infrastructure, like electricity and water, while others were missing bathrooms. Only one had internet. As a result, we would move from house to house for daily activities. To bake, we would use the house with the oven; to print, we would go to the house with the printer; to wash, to the one with the washing machine; to hang clothes, to the one with the sunniest balcony. The things we brought, like tools or books, were shared and spread between different houses. We spilled over into outdoor spaces when our houses were too small to host bigger dinners. We took care of all of our houses, as well as the spaces in between. Our houses were always open, and we moved through them as if moving through rooms. Pedestrian paths became open air corridors. The village became our house.10

Robida having dinner. Photo by Elena Rucli.

Robida’s Academy of Margins in 2022. Photo by Elena Rucli.

Robida meeting. Photo by Tanja Marmai.

Robida having dinner. Photo by Elena Rucli.

Each space morphs with the change of seasons. In the summer, our houses are corridors, squares, almost-public bathrooms, and common kitchens. The dining room is a green lot with a big table—the only outdoor shaded space—and in the evenings becomes a cinema. The living room is the small pebbled streets, the low walls, the garden. The shower is the stream in the valley below the village. In the winter, however, the house shrinks. With only a wooden stove for heat, most of the rooms are too cold to be used and remain empty, waiting again for spring and summer. In winter, life is still, and, in this stillness, we plan and desire the fullness, commonality, and publicness of summers. What we use and understand as a house is cyclically expanding and retracting with the rhythm of the air’s temperature. A wide, branched out house, decentralized in many outdoor and indoor interconnected spaces in summer becomes an intimate, curled up space in winter. As temperatures follow the seasons, our house breathes.

We also take care of the landscape, cutting brambles, small trees, or ivy growing in abandoned terraced fields. While we originally did this solely for the pleasure of discovering grown over dry-stone walls, these eventually became common spaces to be used and maintained, though without any productive goal. We occupied wild pieces of land and transformed them into common gardens, which feed our many summer guests. By creating and tending to the garden, our older neighbors came to understand that we were planning to stay, that this was not merely a temporary phase between the end of our studies and the beginning of our new lives. The garden became a sign of our presence, care, and rootedness.

In 2023, we introduced three colonies of honeybees in Topolò/Topolove.11 The apiary quickly became a place where old and new inhabitants, guests, and friends would gather. As such, it is a place where people share tasks, tools, and words. But the bees also do their own form of gathering, bringing pollen and nectar to their hives to create honey, and with it the smells and tastes of the landscape. Bees thus also partake in maintaining and renovating the landscape. While we maintain the old orchards, take care of their dry-stone walls, cut the grass growing between fruit trees, and plant new trees, the bees pollinate the flowers, encouraging fruit production and stimulating biodiversity.

Heavily depopulated and surrounded by a prosperous forest, only a minority of the inhabitants of Topolò/Topolove are human. Village residents share and negotiate space daily with salamanders, ants, brambles, and ivy. The dense, young, and humble forest embraces the village. There are liminal spaces where the village becomes forest: ruins of old houses, abandoned agricultural fields, paved paths overgrown by grass, old dry-stone walls still covered by ivy. These traces of human inhabitation leave space for the lively communities of vegetal and animal beings. If our practice of renovation is rooted in staying with the place and restoring relationships, we must recognize the agency of other creatures doing the same—taking up and producing space, moving through it, occupying it, and caring for it. This is not to say that plants and animals are always peaceful collaborators: trees can ruin old stone walls with their roots, wild boar can destroy paved paths by stepping too heavily on them. But if renovation emerges from a continuous and collective process of dwelling, using, and transforming a place, then these animals and plants encourage us to consider retreat—the willingness to withdraw and cede the human landscape back to nature—to be among its reparative set of practices.12

Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016).

Jeanne van Heeswijk, “Preparing for the Not-Yet,” in Slow Reader: A Resource for Design Thinking and Practice, eds. Ana Paula Pais and Caroline F. Strauss (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2016), 45.

The Protection Law for Slovenians in Italy was passed by the Italian Parliament in 2001.

Florence Krall, Ecotone: Wayfaring on the Margins (New York: State University of New York Press, 1994), 4.

Walter D. Mignolo, Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 85.

Mignolo, Local Histories/Global Designs, xiv.

van Heeswijk, “Preparing for the Not-Yet,” 47.

The art festival Stazione di Topolò/Postaja Topolove, whose artistic directors were the founder Moreno Miorelli and the architect Donatella Ruttar, was established in 1994 and ended in 2022.

A documentary film from 2011 about Stazione di Topolò/Postaja Topolove, by the film director Anja Medved, portrays some young Robida members in their teenage years already dreaming of moving to the village and living there. Anja Medved, “Postajanja_Postaja Topolove /Stazione di Topolò 2011 by Young Topolonauts and Anja Medved,” YouTube, August 26, 2018. See ➝.

The definition “village as house” comes from the master’s thesis of Janja Šušnjar, member of Robida collective, who lived in the village for six months. In her thesis, she interpreted this concept as a renovation methodology of rural villages. See Janja Šušnjar, Projektna študija novih oblik prebivanja v kraju Topolò/Topolove, master’s thesis (Ljubljana: Faculty of Architecture, 2019).

Village as Ecological Entity: Introducing Bees in Topolò was a workshop initiated by Rosario Talevi and guided by the beekeeper Erika Mayr. It aimed to question the role and relation between human and other-than-human inhabitants in the village by welcoming 30,000 new inhabitants, the bees, to the village and landscape.

About this topic see Rosetta S. Elkin, Landscapes of Retreat (Berlin: K. Verlag, 2022).

Framing Renovation is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Ljubljana within the context of the 2023–24 LINA Architecture Program.