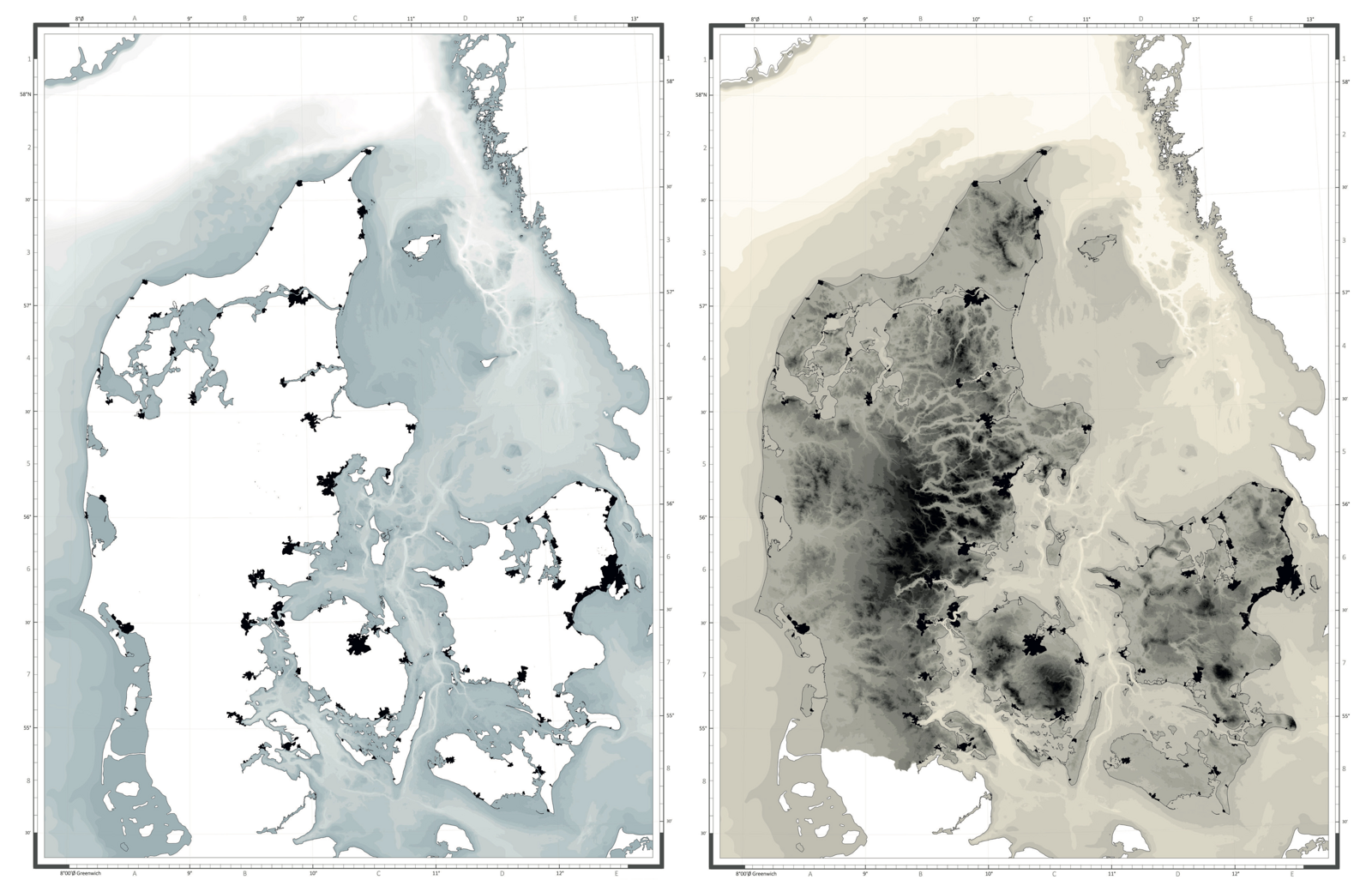

The speed and magnitude of rising sea levels are the cause of considerable levels of uncertainty and flood risk in coastal communities.1 Approximately 10% of Earth’s population live in coastal areas less than ten meters above relative sea level, and 40% live within 100 kilometers of the coast.2 Denmark has followed global trends in concentrating new urban development in low-lying former wetlands and land that has been reclaimed from the sea, both of which are flood risk zones. According to a 2023 report from the Danish Economic Council, “In the period 2009-2020, 8,000 more homes were … built in areas that are at risk of flooding in the future than in areas that are expected to be safe in this respect.”3 Despite the countless reports that indicate the steady increase of sea-level rise and storm surges, many Danish coastal cities have been developing their harborfronts in ways that make them unnecessarily vulnerable to these changing conditions. Out of fifty-four case studies of Danish coastal cities studied in the Little Blue Atlas research project at the Aarhus School of Architecture, all have built in flood risk zones since 2011, and the majority have plans for further urban development in these areas.4 If they continue to follow this trajectory, these cities may reach a so-called “point of no return” that could necessitate massive reinvestment in costly protection measures such as dikes, sluices, sea walls, and pumps.

Smaller coastal towns in Denmark have largely mirrored the approach to urban development and the types of projects built in larger cities, which feature a flamboyant use of building materials in multistorey, heavy, concrete buildings. When sited upon wetlands and swampy ground, these kinds of buildings require significant amounts of material for foundations, which, beyond other issues, creates high carbon emissions.5 That small coastal towns build in the image of larger, prospering cities is perhaps not surprising. However, their exposure to flood risk differs, as smaller towns have fewer economic interests and a smaller tax base, and therefore less capacity to adapt to a changing climate than larger cities. Settlement patterns and building typologies on the Danish coast currently represent a “one size fits all” approach, where similar urban development patterns and building trends are applied without attention to landscape characteristics, such as terrain and soil conditions or local urban characteristics.

Building on former wetlands and reclaimed seabed comes with a cost, particularly in terms of material use, and, thus, greenhouse gas emissions, as business-as-usual building practices require considerable foundations. The diagram shows a building named The Lighthouse in Aarhus. It is 142 meters high, with a sub-surface span deeper than 70 meters.

The consequences of neglecting landscape characteristics and dynamics have been well described by planner and landscape architect Ian McHarg,6 as well as landscape architect Anne Whiston Spirn, who coined the term “landscape il-literacy.”7 Even though methods for designing with nature have been well-documented and elaborated for over half a century, these understandings, methods, and principles are generally not applied in urban development. For example, coastal towns sited in low-lying areas, such as Lolland Island or by the Wadden Sea, will have to find solutions within this lower terrain—such as designing for disassembly, waterbased structures, island-based urbanism, or retreat—whereas the Eastern Jutland Fjord cities are located near higher ground, and therefore have the more simple option of building there instead. Thus, one size does not fit all when it comes to climate adaptation. The landscape in itself presents different potential responses to rising sea levels. Perceiving the coast as a dynamic zone is key to recontextualizing and changing urban development, planning, and building practices in coastal cities.

The coast as a line or a zone

Rising sea levels challenge the notion of the coast as a line. The coast is a zone in constant flux with different temporalities and spatial implications, from tidal movements and lunar cycles to storm surges and sea level rise. Rising sea levels create a condition called “coastal squeeze,” in which species living in lower coastal waters need new habitats and are forced to migrate further inland. However, if the future coastal zone is blocked by hard, steep edges, migration is not possible. The spatial characteristics of a harbor edge or other hard protective structures can make the consequences of coastal squeeze more severe for biodiversity.

Climate change and the biodiversity crisis create an urgent need to improve the practices of co-habitation between human beings and more-than-human species in urban developments along the coast. As opposed to what is often the case in larger cities, many smaller towns have relatively large areas of former or continuing harbor industries. These “leftover” or surplus areas are strategically well-sited to provide nature-based solutions to rising sea levels, such a wetland buffer zones that attenuate waves during storm surges at the same time that they provide space for other species and accommodate sea-based recreation.

Early nineteenth century painting of the coastal town Vejle, showing the typical siting of coastal towns in Eastern Jutland; that is, on a hill surrounded by buffer wetlands and a ford, with convenient access to the fresh- and salt-water needed for vital functions as well as for transportation and trade. Image: Søren Lange (c. 1821), © Statens Museum for Kunst.

Settlement patterns of building flood risk

The reclamation of former wetlands for urban development leaves less room for water coming from the hinterland, as the compaction of soil and construction of impermeable surfaces hinder the sponge effect of soil and natural wetlands. Furthermore, building on swampy, unstable soils requires considerable numbers of heavy, deep, concrete pillars, which take up valuable space under the surface and contribute to subsidence. This all diminishes the potential of wetlands to be used for the common good, for example, by relieving other areas of excess surface water or by offering nature-based solutions for adaptation, mitigation, and biodiversity. Additionally, if there is severe sea level rise, urban relocation or retreat may very well become necessary. If there is a need for future abandonment, not only will these investments be left behind, but so will these underground infrastructures, which are too deep and inflexible for reuse.

Former industrial areas or newly-reclaimed harborfronts tends to have hard edges and be sited on lower grounds. Originally, hard edges responded to the practical need for vessels to load and unload goods, and the lower ground facilitated railway connections. When these harborfronts become dense residential and mixed-use areas, however, those functions likewise become obsolete. Hard edges increase the energy with which waves hit, in addition to increasing coastal squeeze and flood risk. Given the fact that dense concrete buildings are capital intensive and hard to move, further hard structures such as larger dikes and seawalls might be necessary to protect them from rising sea levels in the future. In smaller cities with a smaller tax base, such costs could be overwhelming for future citizens, which may lead to cuts in welfare systems such as public schools or health care. As a result, building dense neighborhoods in flood risk zones in smaller coastal towns can lead to intergenerational inequity. It also raises questions about who is financially responsible for the long-term consequences of buildings on low-lying and wet areas.

Flexible land use designations, as well as rental contracts that either allow for land-use adjustments to keep expansion in check or a “spatial timeframe” based on the pace of groundwater or sea level rise, would each provide opportunities to build more responsibily in former industrial areas or newly-reclaimed harborfronts. These areas are also suited for adaptation and mitigation through the use of trees or salt marshes that function as carbon sinks and keep moist in dry seasons, in addition to providing circulation, recreational sites, and public health benefits. Beyond this, however, urban development can be incentivized elsewhere, like in the historical centers of harbor cities, which are often nearby harborfronts but on higher ground. And when development does take place on the harbofront, it could be done as infill with light construction and light foundations: a light and adaptive urbanism.

Underestimated Potentials

While coastal cities face an increasing urgency to adapt to rising sea levels, contemporary construction of dense urban development in low-lying coastal ares and flood risk zones exceeds the pace of adaptation measures. Harborfront development often takes place on reclaimed land, such as former wetlands or seabed, which further increases flood risk in areas where climate adaption is already needed, leaving the consequences for future generations. It is time to incorporate dynamic and nature-based solutions into the design of coastal cities.

Small towns have considerable transformative capacities. Smaller coastal towns could choose a more contextualized approach to urban development, one focusing on transformation that takes into consideration local and regional landscape characteristics, as well as the existing building stock. If they would, there is significant potential for a renewed, climate-sensitive approach to light urban development with space for both humans and non-human species.

Katrina Wiberg et al., The Little Blue Atlas (Det Lille Blå Atlas: Undersøgelser på Danmarkskort af relationer mellem hav, kystby og land) (Arkitektskolens Forlag, 2022), see ➝, is part of a shared research project “Coastal Cities and the rising sea – new solution spaces” by Aarhus School of Architecture, Copenhagen University, and Danish Technical University.

“Factsheet: People and Oceans. The Ocean Conference, United Nations, New York 2017”, United Nations, June 5, 2017, see ➝.

Carl-Johan Dalgaard, Mette Ejrnæs, Lars Gårn Hansen, and Jakob Roland Munch, “Boligejere med havudsigt bør betale mere,” De Økonomiske Råd, Feburary 10, 2024, see ➝. Translation by author.

The selection follows a report on expected storm surge damage costs over the next hundred years in 48 Danish Coastal cities (COWI, Byernes udvikling ift. udfordringerne med havvand og stormflod (Realdania, 2017); COWI, Byernes udfordringer med havvandsstigning og stormflod (Realdania, 2022)). The number of case studies, however, increased from 48 to 54 to include a pool of cities that have participated in the project “Cities and the rising sea-levels” by Realdania in order to make further use of existing knowledge from this project.

With increasing urbanization and projected population growth in coastal zones—and with only 15% of the world’s natural coastlines intact—these practices are also of concern in the biodiversity crisis. “Population Facts. The Speed of Urbanization around the World,” United Nations Department of Economic & Social Affairs, Population Division, December 2018, see ➝; “World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision,” United Nations Economic & Social Affairs, 2018, see ➝; “Factsheet: People and Oceans,” The Ocean Conference, United Nations, New York, 2017; Douglas Brown, “Only 15% of the World’s Coastlines Remain in Their Natural State,” World Economic Forum, February 15, 2022, see ➝.

Ian L. McHarg, Design with Nature (New York: Doubleday, 1969); Anne Whiston Spirn, “Woodlands New Community: Guidelines for Site Planning” (1973), see ➝; Frederick R. Steiner and Ian L. McHarg, eds., Design with Nature Now (Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy in association with the University of Pennsylvania School of Design and The McHarg Center, 2019).

Anne Whiston Spirn, “Ecological Urbanism: A Framework for the Design of Resilient Cities” (2012), see ➝; Anne Whiston Spirn, “Deep Structure: On Process, Form, and Design in the Urban Landscape,” in City and Nature : Changing Relations in Time and Space (Odense: Odense University Press, 1993), 9–16; Anne Whiston Spirn, “The West Philadelphia Landscape Plan: A Framework for Action” (Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning at the University of Pennsylvania, 1991), see ➝; Anne Whiston Spirn, The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design (New York: Basic Books, 1984).

Framing Renovation is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Ljubljana within the context of the 2023–24 LINA Architecture Program.

Category

Subject

The essay is based on research conducted at the Aarhus School of Architecture: What are we building on the edge to the future? (Katrina Wiberg, project lead, Martin Odgaard, Amalie Lykke Baadsgaard, Eirni Angeli, and Jakob Ørum), and The Little Blue Atlas (2022) and Postcards to the Future (2022) (Katrina Wiberg, project lead, and Tom Nielsen, with Sissel Sønderskov Rasmussen and Simone Stellô Stelsø Lauridsen as research assistants).

The Atlas and Postcards projects are part of the research Coastal Cities’ Solution Spaces over Time (Kystbyers løsningsmuligheder over tid), a joint project between the Danish Technical University (DTU), Copenhagen University, and Aarhus School of Architecture. The research is co-funded by the philantrophic foundation Realdania.