Nick Axel: Your recent work in Italy looks at renovation beyond the material condition, towards a more historical, political, and almost metaphysical condition. Can you start by introducing your project at Borgo Rizza and the Entity of Decolonization?

Alessandro Petti: A series of villages were built during the fascist regime in Sicily by a governmental agency called the “Entity of Colonization of the Sicilian Latifundia” (Ente di Colonizzazione del latifondo Siciliano). These “entities” were built with the specific idea of colonizing the countryside, which was understood as underdeveloped and in need of modernization. One of these towns is called Borgo Rizza, which is in between Catania and Syracuse. This new town was supposed to work as a part of a network of small rural settlements, which usually featured a nucleus of approximately seven or eight buildings, including a post office, school, church, a Casa del Fascio (which at that time substituted for the municipality), and a building called the “Entity of Colonization of the Sicilian Latifundium.” After working in Palestine for more than a decade around decolonizing architecture, it became interesting for us to look at Europe and its difficult heritage: problematic histories that have gone unacknowledged, or whose processes of reconciliation have been interrupted. In architecture, one example of this is Italian colonial–fascist architecture.

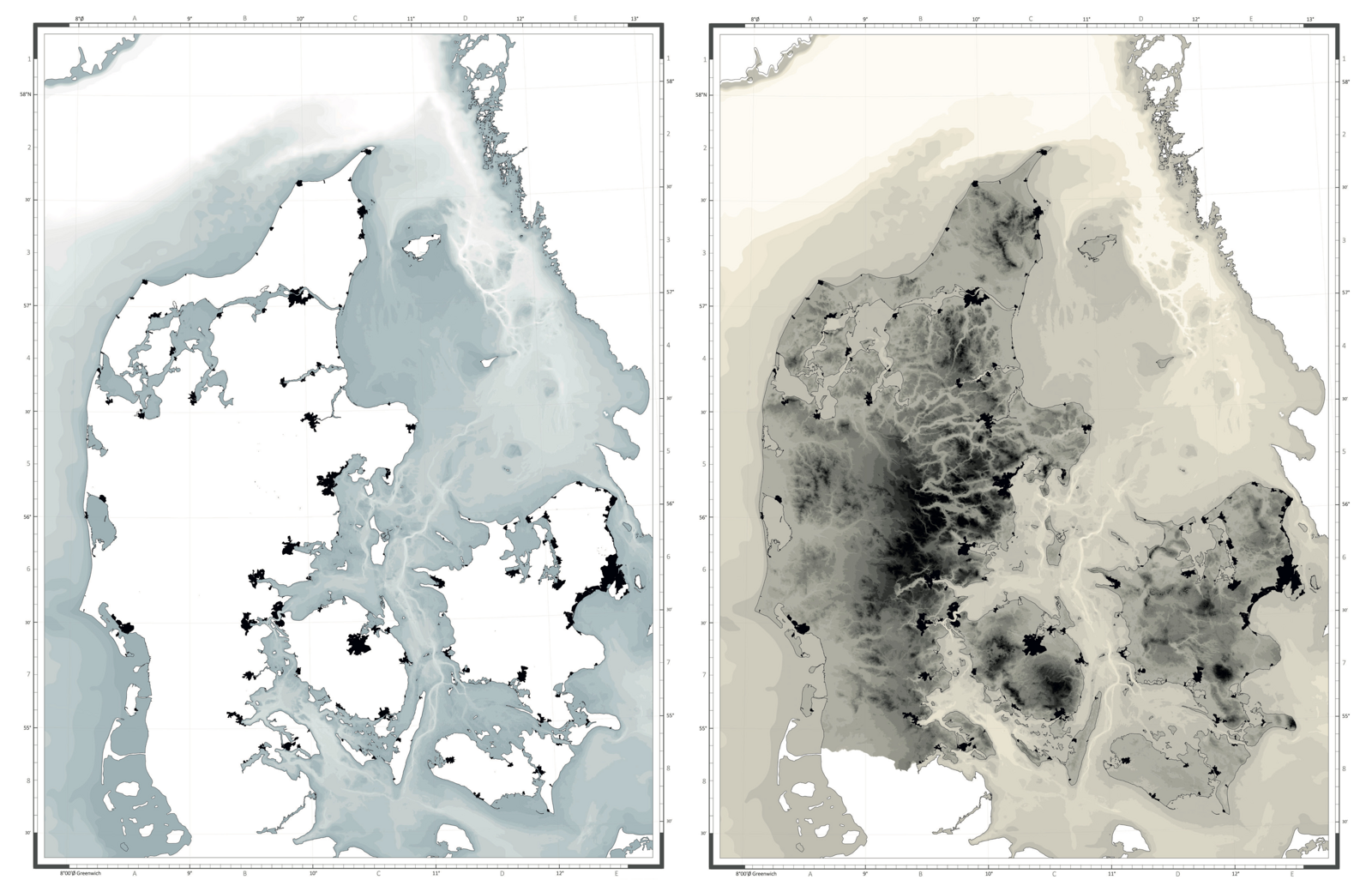

Sandi Hilal: When we began working in refugee camps in Palestine, we realized that decolonization necessitated a rethinking of the entire aid system, which often renders people as mere victims, neglecting their agency and political subjectivity. What would it entail to decolonize Europe with a similar approach? Although Sicily is part of Italy, it was deemed backward by the Fascist regime and subjected to colonization, veiled in the rhetoric of “progress.” The architectural interventions implemented in Libya were replicated in Sicily, even by the same architects. Europe holds a deep history of internal colonization, often overlooked, yet that is manifested in its architecture. Our initiative involved transforming the former Entity of Colonization in Borgo Rizza into a space to think about practices of decolonization in Europe.

NA: You reflect on the task of decolonization within Palestine as something that obviously goes beyond any sort of formal structure—that it requires dismantling systems and subjectivities. In Sicily, are there analogous systems and subjectivities, beyond the ideology of fascist architecture?

SH: When we got to Sicily, we checked out local NGOs helping migrants as a possible point of departure for rethinking decolonization in Europe. But we realized it’s not just about bringing refugees here to think about decolonization in Europe. Europe has already colonized much of the world—now, are we expecting refugees to solve Europe’s decolonization issues? It felt like the only option at first, but we instead decided to start with ourselves. Alessandro is Italian, and I am Palestinian. I have Italian citizenship, but I feel that the fascist façade of the Entity of Colonization tells me that I will never become Italian. Fascism firmly distinguished between who can be Italian and who cannot. Our goal is to question and destroy that kind of frame.

AP: Entities of Colonization had the task of providing infrastructure and housing for those colonizing land that was understood as empty, unproductive. In that sense, one can read the formal qualities of their modernist architecture as a response to this imaginary “tabula rasa.” During the Fascist regime, Entities of Colonization were built both in Sicily and Libya, and their aim was the same. There were even ways of speaking Italian at the time to say that Sicily was similar to “Africa.” But then, at the end of the Second World War, Italy lost its colonies at the same time as the Fascist regime fell. Paradoxically, this interrupted a (potential) process of decolonization, and, shortly thereafter, the process of defascization was interrupted as well. Decolonization never took place because Italy simply lost its colonies, and processes of defascization were stopped in the 1950s due to fears of Italy becoming a communist country. But in the context of Italy, decolonization and defascization are intimately linked.

Italian fascist colonial architecture in Asmara, Eritrea. Photo: Luca Capuano, 2019. Courtesy DAAS.

NA: We can see that with increasingly clarity as we watch the resurgence of fascist ideology in Italy today.

AP: It never left. Most of its architecture is still there. It’s not uncommon, for instance, to enter into a post office in Italy and see a statue or plaque of Mussolini with an imperial declaration, as was typical at that time. What has happened since then, however, is that fascist architecture has become normalized. One of our goals at Borgo Rizza is to de-normalize this architecture; to critically reflect on the very fact that this architecture was not demolished. Today, most of it is actually in need of restoration. And it’s almost 100 years old, so technically, it’s about to officially become Italian heritage. The trick that architectural historians have used to evade problematizing this difficult heritage has been to separate its formal aspects from its political, social, and environmental motivations. With our interventions at Borgo Rizza, we’re attempting to reconnect this architecture to the historical moment when it was produced, but also to reintroduce it into the present. At a time in which migrant populations continue to arrive in Sicily from former colonies (Libya, Eritrea, and Ethiopia), it is necessary to ask, who has the right to use this colonial–fascist architecture?

NA: What happened to Borgo Rizza after it was abandoned? How would you describe its context today? What kinds of relationships do people have with the site?

AP: What we have heard from residents from the nearby town of Carlentini is that, before the invention of shopping malls, people would gather at Borgo Rizza in the summer on hot afternoons to eat watermelon and watch the sunset. It was also a place where people from Carlentini getting married would go and take photos. It was a place for social gathering, but it was never really reinhabited. That said, the municipality has constantly promised to renovate and somehow reuse it. One of the reasons this political promise has never been realized, we believe, is because its histories has never been fully acknowledged. But this means that when we went to the municipality of Carlentini and started to talk with them about working on the site, the mayor said “yes, please, we were waiting for you.” We’ve organized three annual gatherings there so far, but the municipality has also started a process with local associations to think about how to continue using the site.

During the third annual Difficult Heritage Summer School at Borgo Rizza in 2024, a new plaque was erected to the new Entity of Decolonization. Photo: Herman Hjorth Berge.

NA: What did it take, and what has it meant to reuse the structures at Borgo Rizza for these gatherings?

AP: The first building that was reactivated was the former Entity of Colonization building, which we renamed the Entity of Decolonization. The second was the post office, which we have turned into hostel, a place where students, for example, stay for free when they visit. The third was the former school, which is now used for exhibitions. Every time we gather, we try to physically renovate some of the buildings. But this has been a somewhat complicated process. When we clean and fix these building, we need to make sure that we are not simply restoring them as fascist architecture. Instead, we reappropriate them for different uses.

SH: Working in places like refugee camps, we have been confronted with the condition of permanent temporariness and the imperative to act in the present while defending one’s own past and striving for a just, better future. When we arrived at the municipality of Carlentini in the summer of 2020, we proposed initiating a summer school, without waiting for funding to come through.1 We acted upon what we had. We believed we needed to begin using the site immediately to demonstrate its potential. Understanding the importance of this place to the local government is crucial. Borgo Rizza is public—it’s owned by the municipality. Despite its significance, the municipality has been frustrated by its inability to utilize it fully. We supported each other in transforming the former Entity of Colonization into an Entity of Decolonization, open to practices engaging with difficult heritages.

NA: How did you begin to do this?

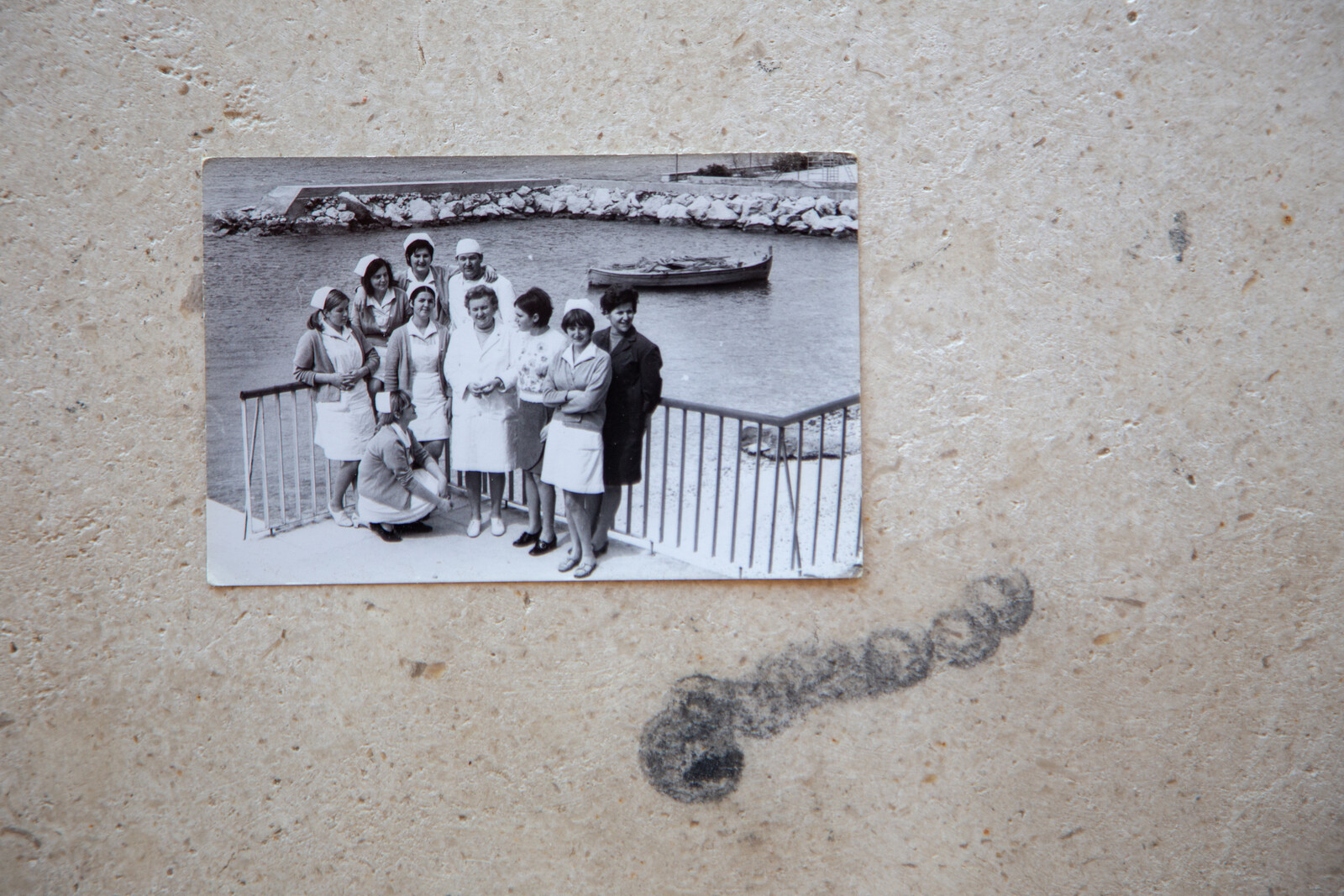

SH: The first action we did was ask the municipality to collect all the old furniture that people from Carlentini did not need and moved it to Borgo Rizza. Many people donated different kinds of items, including tables, chairs, lamps, sofas, carpets, and more. When we put everything in front of the buildings, tons of people from the village came and started to share stories, identifying which furniture used to belong to members of their family. This made people feel like they had the right to be there and take part in the conversations. But beyond this, it created a sense of intimacy with the place. We brought everything that was usually kept private out into the public. Then we brought watermelon, and parents began to share memories with their children about how this is what they used to do, how they spent their summer when they were young. This started a process in which people and the municipality alike started to recognize this place not as a distant memory or a burden, but as something present. Being there, people began to face the history of the site.

NA: Your idea of renovating this place seems to be predicated on a practice that needs to be embodied and performed. Ultimately, it’s a question of use. You mentioned that there are a number of these other towns that are being renovated under a very conventional regime of renovation, which ultimately serves either exploitative tourist industries or politically questionable and amnesiac pride. How do you see what you’re doing in relation to these other regimes of renovation?

AP: Another similar village, called Borgo Bonsignore, was actually renovated by Google in 2015 because they wanted to recreate the atmosphere of the 1930s for one of their annual meetings. Today it’s really popular for some reason with French tourists. Colonial nostalgia is still very attractive for some people. This gets even more complicated in a place like Asmara in Eritrea, which was nominated as a World Heritage Site in 2017 specifically for its colonial–fascist architecture built by Italians. This kind of aestheticization is now embraced by the right-wing in Italy and used to legitimize contemporary neo-fascist or post-fascist political movements. What we propose, in opposition to all this, is to profane this architecture, which means to reintroduce it to common use. Fascist colonialism was essentially a form of expropriation, even though it was done by the state. Entities of Colonization were built as propaganda; they were just a façade for parades. Their interior program was not actually defined, because it didn’t really matter what happened in them. They were only built for photographs and to show that the regime was modernizing. Fellini used a lot of fascist buildings in his movies because their façades were like stages; all you had to do was add people. So, in this sense, to actually use them, to make them tangible, inhabitable, to change their image, is an act of profanation.

Eating and sitting on the artist’s copy of Ente di Decolonizzazione: Borgo Rizza in front of the Entity of Colonization in Borgo Rizza. Photo: Herman Hjorth Berge.

NA: These interventions and acts of renovation that you’ve done have been quite light, but also very effective. But do you feel that the façade can remain as is?

SH: To present the project outside of Borgo Rizza, we actually reproduced the façade of Borgo Rizza’s Entity of Colonization, but deconstructed it in a way to make it a place to sit, eat, and talk. This has allowed us to take the ghost of Borgo Rizza to meet other ghosts of colonization or modernization. During this year’s annual gathering, we brought the façade back to the site and burned it.

NA: You burned the reproduction of the façade at Borgo Rizza? Like in effigy?

AP: When you burn something, it’s often in order to create a new beginning. We didn’t burn Borgo Rizza or the Entity of Colonization itself, but instead a model of it, as a way to bring the Entity of Decolonization into being. Burning is a kind of ritual. The ritual of burning is involved in dealing with death. Burning also creates ashes, which carry their own meaning and have their own set of rituals. They can be spread to create and fertilize something new. It is the closing of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

The third annual summer school at Borgo Rizza in 2024. Photo: Rehaf Batniji.

SH: The installation Ente di Decolonizzazione: Borgo Rizza is a part of the permanent collection at the Museo Madre in Naples, and is currently being exhibited at the Museo delle Civiltà in Rome.2 The artist’s copy, which was burned in Borgo Rizza, aims to breathe new life into the installation by using the ashes to fertilize new projects. It is important for us to establish a connection between the artwork preserved in the museum and the actual intervention on site. In this case, we hope that visitors to the museum will feel encouraged to visit Borgo Rizza, and that the inhabitants of nearby towns will feel supported by the museum in their ongoing and open-ended practices of reappropriation and subversion of their fascist colonial heritage.

The Difficult Heritage Summer School is a collaboration between the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm (DAAS), Royal College of Art (RCA) School of Architecture in London, IASPIS (the Swedish Arts Grants Committee’s International Programme for Visual and Applied Arts), DAAR (Decolonizing Architecture Art Research), Museo delle Civiltà in Rome, and the Municipality of Carlentini.

Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza is a project by DAAR – Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti in collaboration with Emilio Distretti, Sara Pellegrini, Matteo Lucchetti, and Husam Abusalem. It was co-commissioned and co-produced by La Loge—Brussels, the Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, Madre Museum—Naples, and the Comune di Albissola Marina. The project was supported by the Italian Council (10th Edition 2022) program to promote Italian contemporary art in the world by the Directorate-General for Contemporary Creativity for the Italian Ministry of Culture.

Framing Renovation is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Ljubljana within the context of the 2023–24 LINA Architecture Program.