Since the 1950s, most Western European countries have experienced a major migration from rural areas towards larger cities. In most cases, this tendency is caused by a decline in employment in agriculture and its associated industries, as well as the centralization of public institutions.1 In the Danish context, rurality is now marked by depopulating villages with unsellable, abandoned houses and decommissioned public institutions. This disenfranchisement of the rural fuels a reluctance to renovate as an alternative to demolishing and building anew. Furthermore, there is so much rural building stock available and no relevant programs to convert it into.2 While real estate prices have plummeted in the countryside, property prices in larger cities have skyrocketed, with developers demolishing even protected buildings to build anew in order to maximize economic return.

The Danish government is currently taking an approach of “strategic demolition” in an attempt to ease the symptoms of dilapidation in rural villages. In light of all this, the prospects for renovation practices in rural Denmark are challenging. Yet the built rural environment has great significance to society in general, even in its present state of abandonment and devaluation. There is a strong, albeit latent, relationship between the local identities of village communities, collective memories of place, and abandoned buildings. The potential for renovation in these rural villages is not so much about restoring derelict buildings to their original state, but rather rebuilding community cohesion through their transformation.

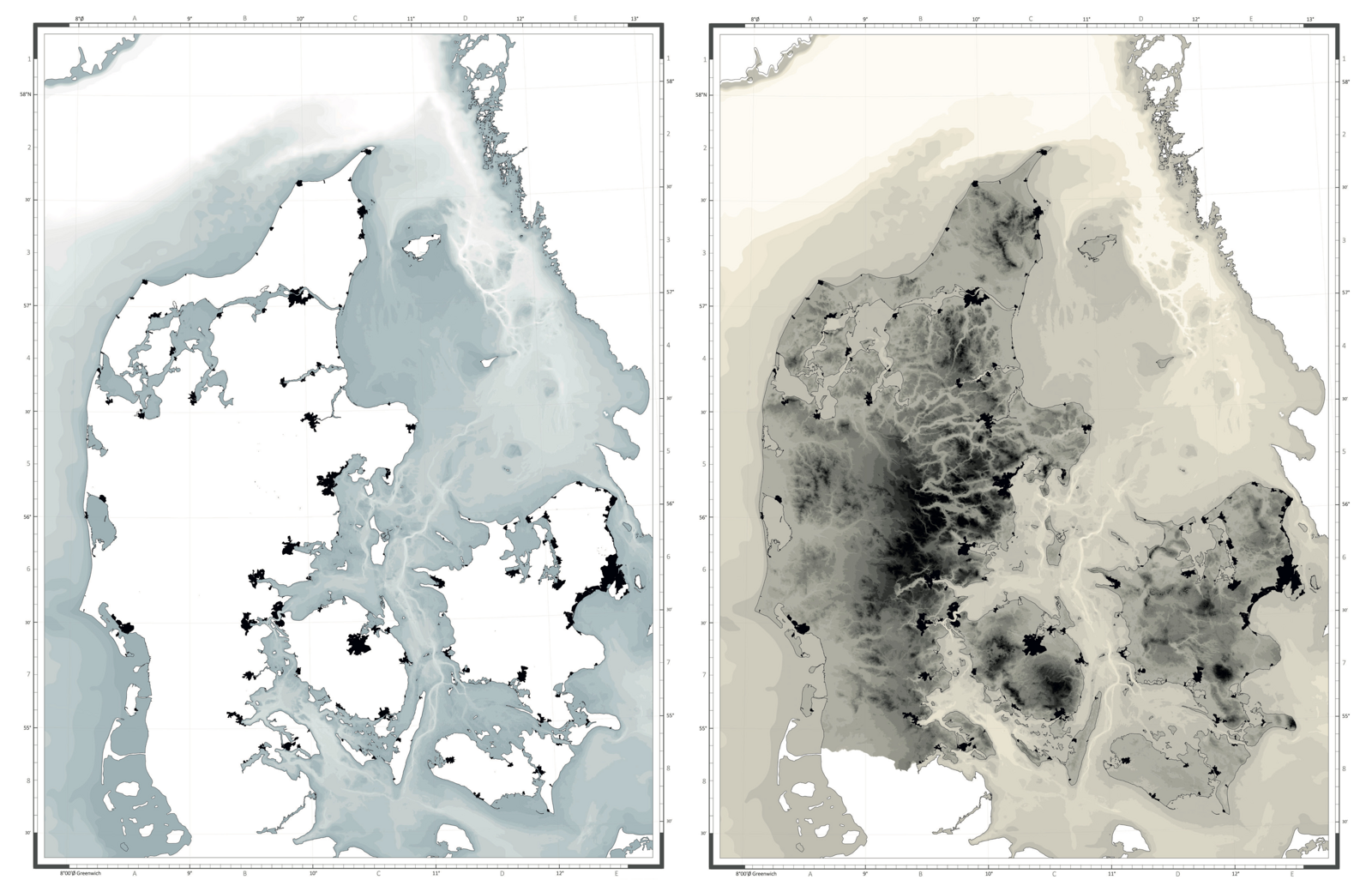

Section of the grocery store in Vestervig showing multiple historic layers. Photo: Mo Michelsen Stochholm Krag, July 2016.

The Grocery Store

In the medieval village of Vestervig, a 150-year-old grocery store used to play an important role in the community as an informal gathering point for local residents. However, it was abandoned in the late 2000s, and in 2010 it was condemned to demolition. Before it was destroyed, however, the local municipality allowed students from the Aarhus School of Architecture to dissect the building with the goal of learning about scale, spatial relations, and materiality.

Partly inspired by the work of Gordon Matta-Clark, we started by cutting the building in two.3 Due to its age, splitting the building in half revealed its entire history as a series of accumulated layers. The grocery store had undergone several renovations throughout its lifespan, and each layer represented a new era, or a major event, in the building’s life. At various places within the building, cinder blocks had replaced or altered the original solid brick walls. At some point in time, the openings in its storefront had been reduced, indicating a transformation of the interior spaces towards more private uses. Newer hollow bricks were also used to expand the building. All these histories were previously invisible, hidden behind plaster and paint.

The continuum of alterations over time was predominantly based on additions and not subtractions. Hence, when a new layer was added, it encapsulated and preserved the previous one. The innermost layers were the oldest, and were primarily structural elements such as brick walls, trusses, and wooden beams. Conversely, the newer layers were closer to the interior as well as the exterior spaces. The ceiling was an accumulation of reinforced plaster, wooden panels, and plaster boards, whereas the floor contained multiple generations of floorboards layered one on top of each other.4 The floor separating the ground level from the first floor consisted of no less than thirteen material layers.

When we started cutting the building, residents from the neighboring community unexpectedly started showing up in large numbers. As they watched the intervention take place, they shared their personal memories of the people who used to live there and their role in the local community. For instance, a father, accompanied by his ten-year-old daughter, instantly recognized his grandfather Wagner Hansen’s signature on the underside of a floorboard, alongside the number 1933, which presumably referred to the year the floor was installed. This ignited a dialogue between father and daughter, in which the merits of Wagner Hansen’s carpentry were passed on to his great granddaughter. All together, these memories represent a collective narrative of the building’s historical role in the community.

While revealing strong relationships between physical buildings and their more immaterial, mnemonic dimensions, this intervention also showed how these memories prove particularly vulnerable. The memories that were revealed along with the layers of the building are site-specific and represent cultural heritage that cannot exist without their material anchor points. The government-led eagerness to demolish what appears obsolete poses a threat to these memories of place, which are important for local identities and, thus, community cohesion. While difficult to identify and therefore easy to lose, their values should be taken into account prior to any act of renovation, conservation, or even demolition.

The Sexton’s House

In the rural village of Snedsted, the local sexton lived in a single-family house on the edge of the cemetery. Originally built at the beginning of the twentieth century and expanded a number of times, it was bought in the autumn of 2013 by the local parish council from its latest occupant, an elderly man who had already moved out and was living elsewhere. The parish council bought the building with the intention to demolish it: they feared that it would continue to decay and become an eyesore next to the medieval church, which was the pride of the village community. Despite this, the parish council, with the municipality’s support, agreed to let the house be used to prototype experimental forms of preservation.

The building had no function and was without any realistic prospect of being converted into anything new. The plan, then, was to leave a neatly curated constellation of remnants to decay. A gentle, precise, and partial demolition process focused on the removal of the building’s lightweight structures, like its roof, ceiling, and windows, as well as minor segments of the brick walls. What remained represented different eras within the building’s lifespan, from 1970s wallpaper- and tile-covered interiors to an exterior with original wall-fragments, foundations, and concrete floors.5 The different eras were easy to identify, as craftmanship, fashion, and changing building codes helped date their origin. One particular room contained a blue, tile-covered bathtub from the 1960s. The exposure of such an intimate space prompted a discussion on the merits of privacy among the local residents. The blue bathtub has since been redeemed as a focal point of the space, and is visible from more than a kilometer’s distance.

The blue bathtub exposed as a result of the intervention. Photo: Mo Michelsen Stochholm Krag, April 2014.

The blue bathtub in decay. Photo: Mo Michelsen Stochholm Krag, March 2015.

The blue bathtub, re-inhabited by the neighboring village community. Photo: Mo Michelsen Stochholm Krag, August 2016.

The blue bathtub, overgrown and turning back to nature. Photo: Mo Michelsen Stochholm Krag, August 2021.

The blue bathtub exposed as a result of the intervention. Photo: Mo Michelsen Stochholm Krag, April 2014.

The intervention intentionally utilizes natural processes of decay and dilapidation as a creative and transformative force. The remnants were left exposed to the climate, which resulted in an acceleration of time. When the unprotected brickwork was exposed to the frost of the first Danish winter, the consequences were severe and prompted an immediate response from the local community. These residents, to whom the ruin was a reminder of better times that were lost, did not carry any affection or romanticism for the structure. As a result, they decided to clean the place up, add plants and benches, and turn the structures into a supplemental recreation space for the neighboring cemetery. The local community still maintains the site today as a recreational space, thus allowing it to continue acting as a site to exchange place-specific memories.6

The Station Town

Bedsted is a rural Danish railway station town with a population of about 830 people. Bedsted dates back to the late seventeenth century, although it was not until the 1880s that the station and the inn were built to accommodate the newly arrived railway, and the town began to flourish. Since the 1950s, Bedsted has suffered from depopulation not unlike many other rural small towns. The question of renovation within the context of Bedsted cannot be reduced to an individual building or set of buildings, but must be thought of at the scale of the town as a whole.

In 2018, an old neighboring forest was planned to be expanded as part of the national Danish afforeststation plan.7 As such, our intention was to redirect and utilize this afforestation to bring the wilderness into the town and interweave the village with the nearby national park. Diluting the boundaries between nature and the built environment has the potential to form new conditions of rural identity, based on plurality and coexistence, which can serve as an alternative to urban life.

Over the course of several decades, abandoned buildings in Bedsted will be transformed into controlled ruins, in a pace corresponding with the speed of the town’s depopulation. Some of these buildings will be reduced to minor remnants such as concrete slabs and wall fragments, which merely testify that something used to occupy this place. Others, however, will be left as larger remnants, and are programmed to maintain clearings in the young forest. These clearings will gradually become cultural and historical gathering points for the local community, as well as resting places for people walking through the forest. Beyond this, a few of the abandoned buildings will serve as portals into the emerging forest.

The gardens of these abandoned properties act as mediators between the condemned buildings and the forest. They weave the two together by allowing cultivated arrangements to dissolve over time and merge with trees of the forest, creating a hybrid nature.8 Ideally, over time, the continuum of spared building remnants will constitute a preserved imprint of the historical town structure that is interconnected by a mesh of forest paths and clearings. Slowly but surely, the controlled ruins will dilapidate and dissolve completely, while the forest and its clearings will continue to mature and change.9 All together, these measures will speed up the transition from station town to low-density forest town, and maybe even generate new formats of re-inhabitation.

Resurrecting aesthetics of decay and repair

Village communities exist in a fragile equilibrium that can be thrown off by strategic demolitions carried out en masse.10 The loss of material and immaterial armatures of local identity often goes unnoticed, as they are difficult to identify and almost impossible to preserve or activate. However, these armatures are of utmost importance in the aftermath of the neoliberal era, in which history is neither valued for its own sake, nor for its bearing on communal matters. Such a deliberate oblivion also applies to the existing urban built environment, as it is constantly under pressure from economic interests.

The grocery store in Vestervig is a reminder that buildings of a certain age represent a fragile spatial-material accumulation of history. What is necessary is an increased awareness of what is already here, as there is always a latent risk of irreversibly eradicating certain historic layers in the quest to safeguard others. The rapid decay of the sexton’s house in Snedsted may also be a reminder that decay is a condition of everything. Thus, it may be time to revive or reintroduce aesthetic ideals that allow for repair, and hence present buildings as historical assemblages. In that sense, Bedsted provides an opportunity and a testing ground, for developing not only re-habitation, but also rewilding, from which new rural identities can grow out of what is already present.

N. B. Grimm et al., “Global Change and the Ecology of Cities,” Science 319, no. 5864 (February 8, 2008): 756–60.

Mo Michelsen Stochholm Krag, “Transformation on Abandonment, a new critical practice?” (PhD dissertation, Aarhus School of Architecture, 2017).

Gloria Moure, Gordon Matta-Clark: Works and Collected Writings (Barcelona: Ediciones Polígrafa, 2006).

Statistics Denmark, ‘Thisted Kommune,’ 2017. See ➝.

Mo Michelsen Stochholm Krag, “Encountering Rural Transformation: A Catalyst for Exchanging Narratives of Place?” Architecture and Culture 5, no. 1 (2017).

Maurice Halbwachs and Lewis A. Coser, “On Collective Memory,” in The Heritage of Sociology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

The Danish Ministry of Environment, “Danmarks Nationale Skovprogram,” (Copenhagen: Miljø- og Fødevareministeriet, 2018).

Mo Michelsen Stochholm Krag, “RURALITY OF RUINS” in Concepts of Transformation (The Nordic Association of Architectural Research, 2023).

Mo Michelsen Stochholm Krag, “A Reality of Rurality” (AR: Arhitektura, Raziskave, 2021).

Pieter Versteegh and Sophie Meeres, eds., Alter Rurality: Exploring Representations and “Repeasantations” (Arena, 2015).

Framing Renovation is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Ljubljana within the context of the 2023–24 LINA Architecture Program.