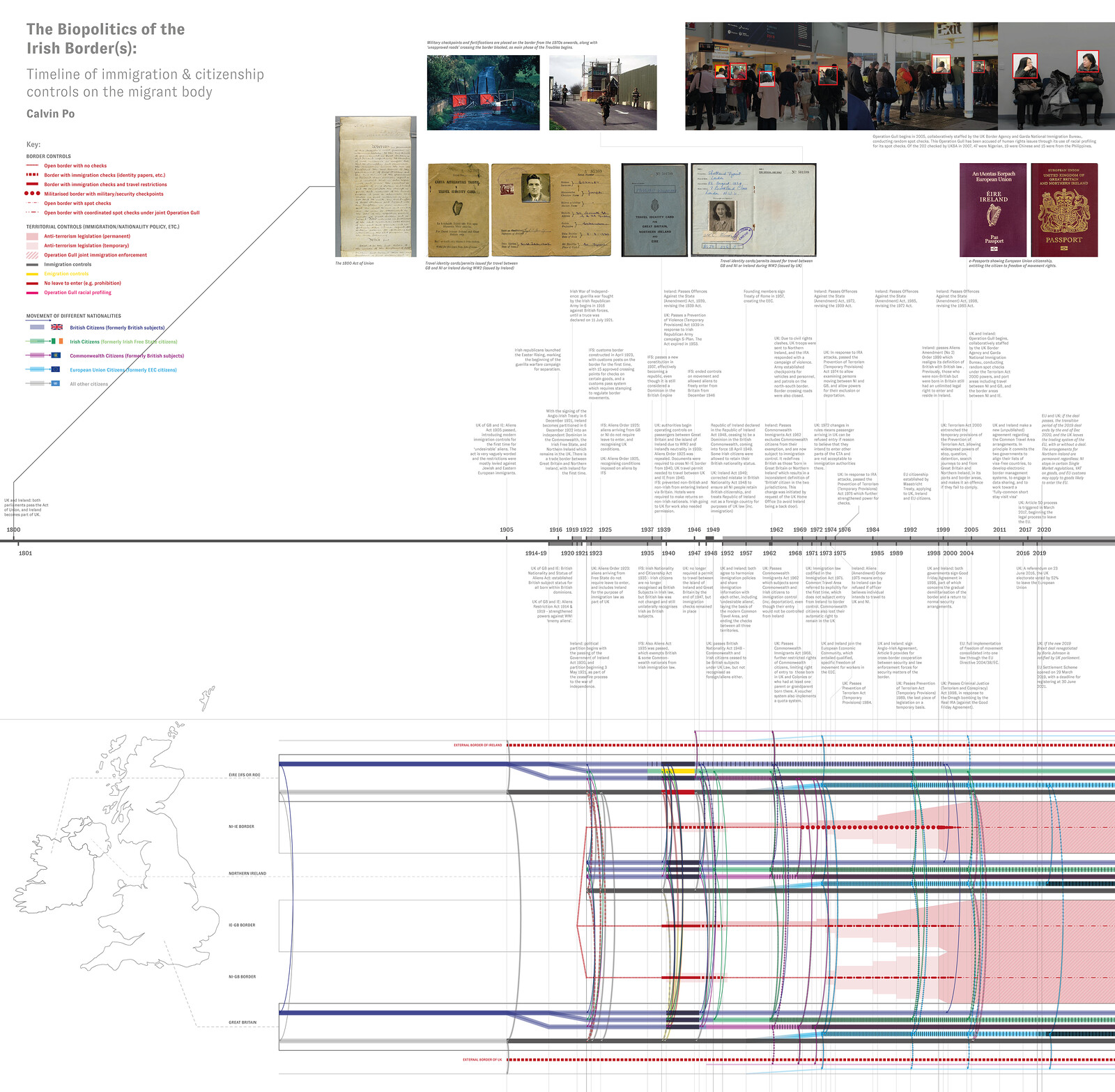

The heraldic symbol of the Red Hand is believed to embody Ulster’s founding legend, in which the first to touch the land in a boat race claims its sovereignty. Exploiting a loophole, one man bloodily severs his own hand and throws it onto the land, thus claiming the territory. This myth contains an echo of the history of Ulster and Ireland’s colonization in what is called the Plantations: from the sixteenth century onward, fertile land was confiscated from the Irish and redistributed to English and Scottish settlers loyal to the British crown(s) who occupied the land through farming, known as “planters.”1 In Northern Ireland’s popular imaginary, the claim of land, notions of sovereignty, territory, and border are all bound to the body, its occupation, and labors on the soil.

During Ireland’s colonization, sovereignty was in constant flux and was determined by the land’s de facto occupation by British or Irish populations. A border, representing an abstract claim of land, was only meaningful as long as it could be enforced and bolstered by these sedentary bodies and their cultivation of the land, and shifted fluidly with the thresholds of actual control. However, when the modern nation-state became formalized as a territorial construct—with sovereignty arising from the soil itself—the border became a de jure threshold of a state’s power. With the sovereignty of territory fixed in law, the body’s act of occupation transforms into an alternate claim on the land. For Northern Ireland’s two divided communities, this comes down to attaining a demographic majority in neighborhoods and counties and culminating in the territory-wide “border poll”: a referendum between the UK retaining Northern Ireland or reuniting Ireland.2 This claim rests on the body’s labor of a different kind: the body’s reproductivity. As the agent of a population’s growth in this reproductive arms race, the fertile body has drawn, and can redraw, the Irish border.

In an equal and opposite reaction, the sovereignty that arises from the soil also translates into the state’s power over the reproductivity of bodies within its territory, through regulating marriage, reproductive rights, and legal gender. In Northern Ireland, this biopower is uniquely magnified. This persisted up until the critical juncture on October 22, 2019 when reforms legalizing abortion and same-sex marriage were imposed by UK Parliament. While this event has emerged from a context where the Irish border has resurfaced as complication of Brexit, the border question of Northern Ireland has deeper roots in the long-standing tension between bodies, soil, territory, and state. With the body’s power to redraw the border, and the border’s power to subject bodies under the state’s biopolitics, the Irish border condition is inscribed by and onto the human body.

The birth of the border

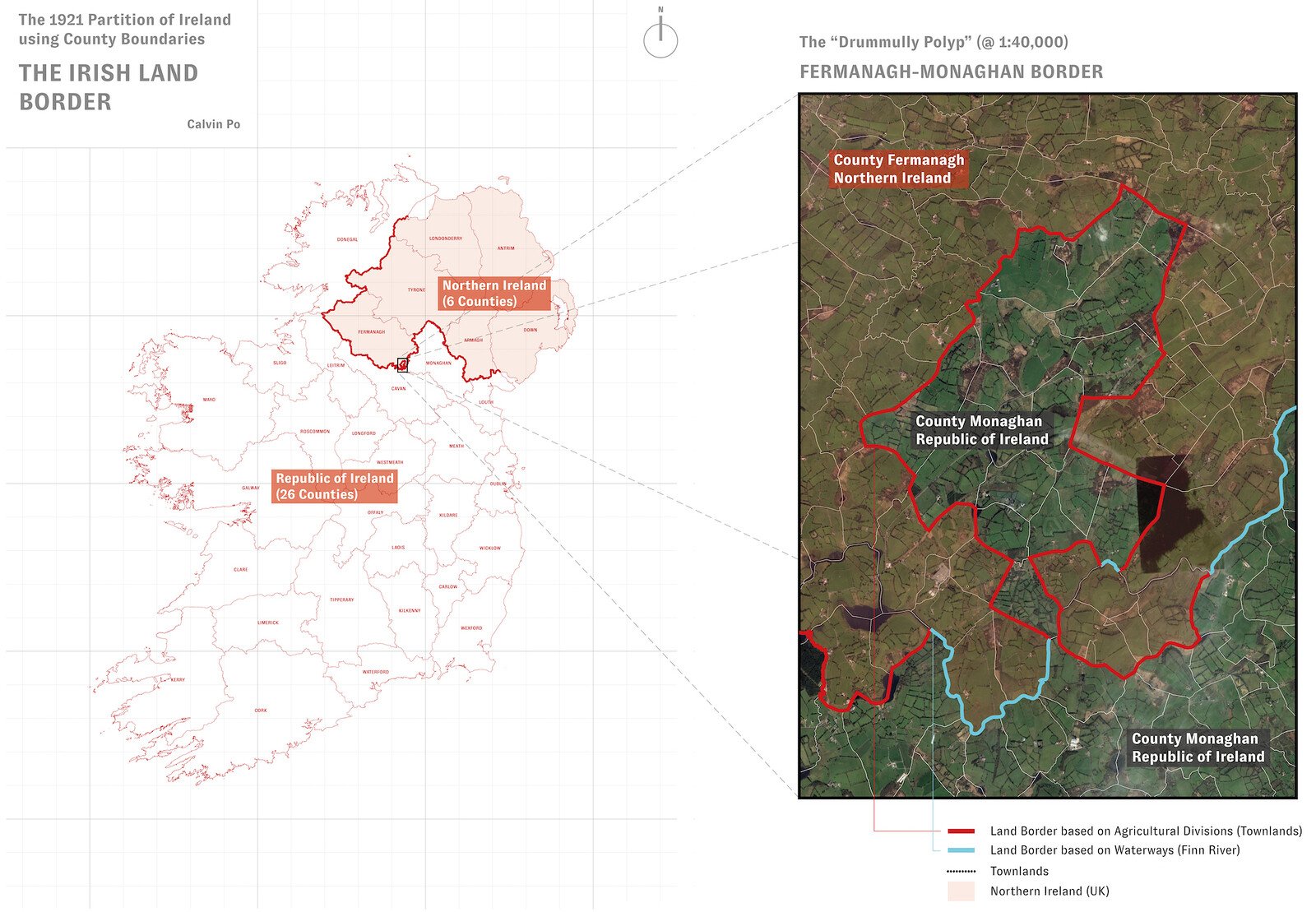

In 1921, Britain’s partition plan carved out six of the nine counties of Ulster to create Northern Ireland, and the Irish Free State became independent from Britain the year after. In the process, Ireland’s divided soils were impregnated with concepts of territorial sovereignty. Now an international border, it is still defined by counties, themselves derived from townlands (baile fearainn), a Gaelic unit of land division tied to the economic and agricultural potential of the land, which is itself based on the fertility of the soil.3 These agricultural divisions, appropriated in the Plantations for mapping, seizure, and redistribution of land, were the basis for the reorganization of the Irish state.

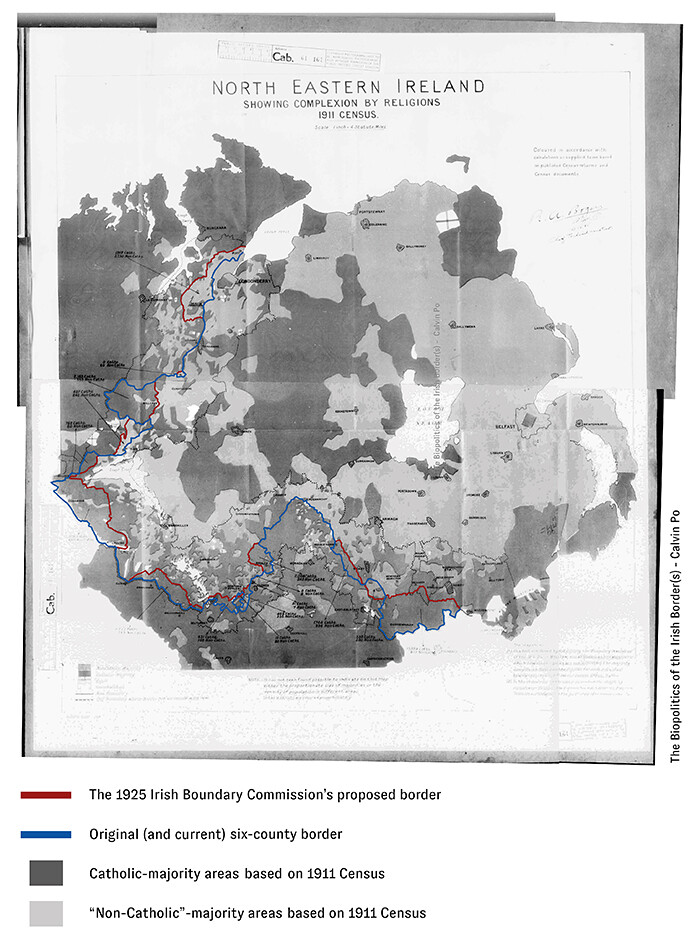

The 1911 Census maps showing interlocked Catholic-majority and “non-Catholic”-majority areas used to draw (and attempt to redraw) the Irish land border. Source: 1925 Irish Boundary Commission, UK National Archive, annotated by Calvin Po.

Traced along these ancient field patterns, a stopgap bureaucratic exercise created the land border to enclose a Protestant, unionist-majority population within its territory to be excluded from a self-ruling, Catholic-dominated polity.4 The legacy of largely Protestant planters (and subsequent settlers from Great Britain) is still legible today in demographic maps, with Protestant populations concentrated in the northeast of the otherwise largely Catholic island of Ireland. The crude simplicity of partition, in carving out a “Protestant-majority” territory, ignored the interlocking, shifting distributions of the Catholic and Protestant populations, leaving sizable minorities on the “wrong” side of the border. This reached a breaking point in Northern Ireland when mutually-exclusive conceptions of the national destiny for this territory—union with Britain (unionism) or reunification with Ireland (nationalism)—co-occupied the same soil and violently disagreed over its rightful sovereignty during The Troubles.5

Since 1998, the Good Friday Agreement has attempted to engineer peace (or arguably, pacification) through a compromise of the uncompromising framework of nation-states. While Britain would retain nominal sovereignty over Northern Ireland, it would be smudged and diluted where possible. Northern Ireland was rebuilt as a devolved legislature and government with power-sharing between unionists and nationalists. New north-south (Northern Ireland-Republic of Ireland) and east-west (Republic of Ireland-UK) forums for cooperation and joint governance were created. The logics of the nation-state—the power to exclude all external interference in its territory’s internal affairs—and the potency of the border—as the device of this exclusion—were eroded in the name of peace.

The Irish land border at Killea, with Northern Ireland on the left, and the Republic of Ireland on the right. Photo by Calvin Po.

The border and its perceptibility have become inconvenient signifiers of which state has actual sovereignty over Northern Ireland. Any tangible sign of the Irish border either on land (signifying British sovereignty) or in the Irish Sea (signifying Irish sovereignty) risks shattering Northern Ireland’s sovereign ambiguity on which this peace is built. From the absence of physical signifiers (border fences and checkpoints) marking the soil, to the erasure of institutional signifiers (the “national” in National Health Service, the “Crown” in Crown Prosecution Service), this indeterminacy is entrenched both at the borders and throughout the territory.6 For the same reason, the “hardness” (namely, the perceptibility) of the Irish borders during and after Brexit stubbornly remains the fulcrum upon which the future relationship of the EU member states and the UK is balanced. Even today, apart from the different units on speed limit signs in miles versus kilometers, or subtle changes in road surfaces, the border is barely perceptible across largely indistinguishable farmland.

Post-Brexit wrangling over trade terms and ongoing tensions reflect the continuing struggle to keep the Irish borders imperceptible to the casual observer. Yet framing the problem through the mercantilist lens of customs and trade ignores the human issue at the crux of the border question. In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt posits that, despite the presumed universality of human rights, they nevertheless depend on a nation-state to be enacted and given meaning. The body’s subjecthood of this framework, its “right to have rights,” is therefore not intrinsic to the body, but is reducible to the body’s inclusion or exclusion within a state’s territorial jurisdiction.7 The “imperceptible” Irish borders then become perceptible as a threshold of rights gained and lost by a body, as it crosses from one sovereign soil to another. Crossing either the land or sea borders around Northern Ireland can entail a change in the body’s age of legal responsibility, employment, sexual and medical consent; rules for same-sex marriages, civil partnerships, deed polls, legal gender recognition; access to cross-gender hormone treatment, abortion rights, maternity leave and pay; and more. A “hard” Irish border may not be marked in the land, but is still inscribed upon each individual body.

Borders in the (re)productive body

The Good Friday Agreement prescribes one route to change the borders—the “border poll”—which hinges on the “consent of a majority of the people of Northern Ireland” to “bring about a united Ireland.” In this, the theater of conflict shifts from a political to a corporeal one, where sovereignty is subject to a reproductive arms race between the unionist and nationalist headcounts, succinctly captured by the firebrand unionist Ian Paisley: “[Catholics] tell us they’ll breed us out. I would say to them Protestants also breed.”8 Predictably, the relative fertility, birthrates, and growth of these religious-political populations is constantly scrutinized and studied. Some claim a 4% higher fertility rate in Catholic versus Protestant women in the post-Agreement decade.9 Others predict an imminent Catholic majority by the time of the 2021 Census (the centenary of Northern Ireland’s establishment as a “Protestant-majority” polity).10

The most tangible effects of Northern Ireland’s supposedly imperceptible borders materialize in the state’s biopower over bodies as reproductive subjects. Underpinning these borders in the body is a biologically-essentialist paradigm of the binary, heteropatriarchal family, with the reproduction of labor power as its metric of productivity. This is further convoluted by the peculiarities of Northern Ireland’s post-conflict settlement, where a lapse of human rights arises from the overlap and semi-inclusion of multiple polities, with both the UK and Ireland making intersecting claims on its body/bodies politic.11 In blurring the border, the Good Friday Agreement created entangled governmental systems where marginalized bodies can fall between the gaps, or be pulled in contradictory directions.

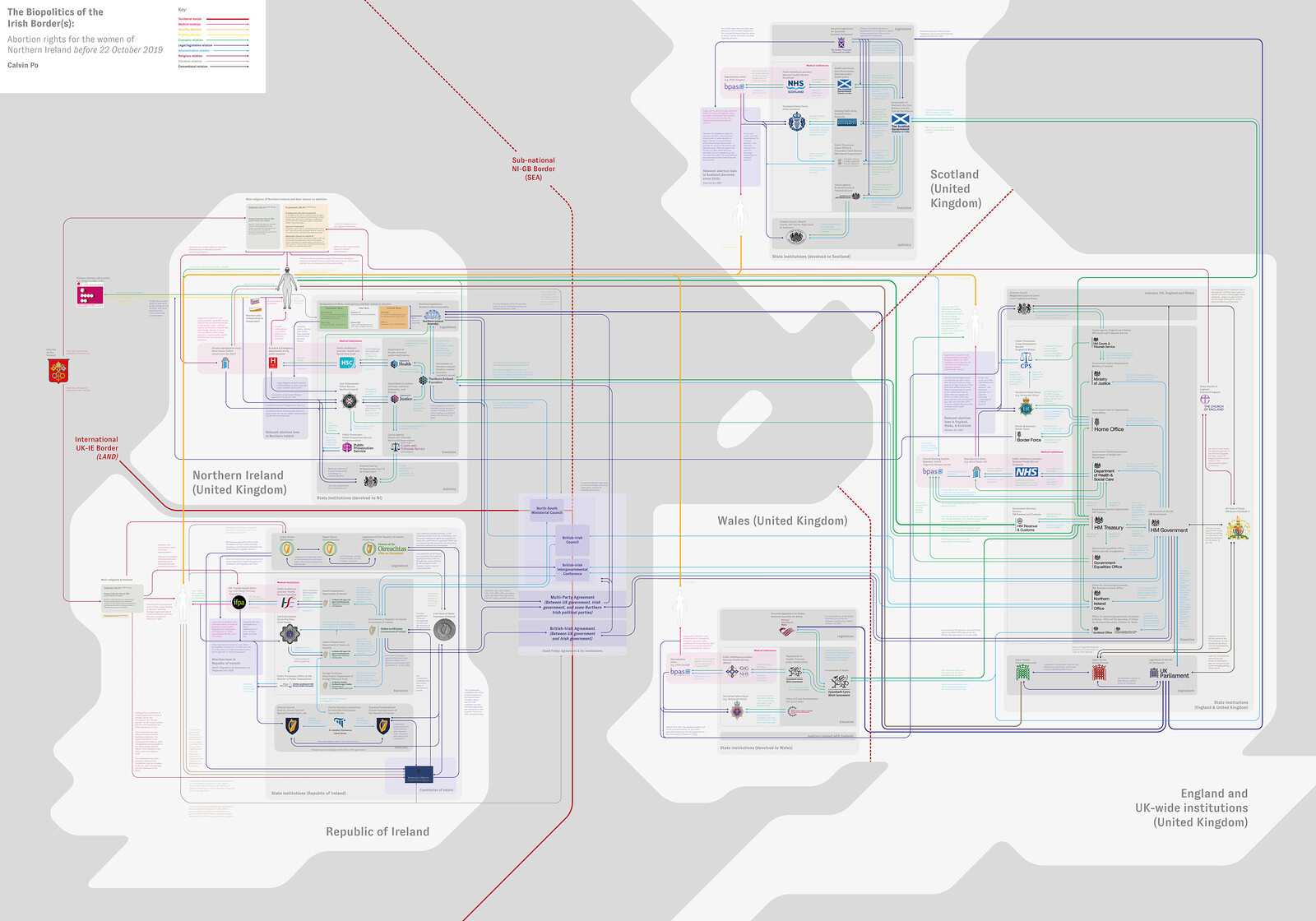

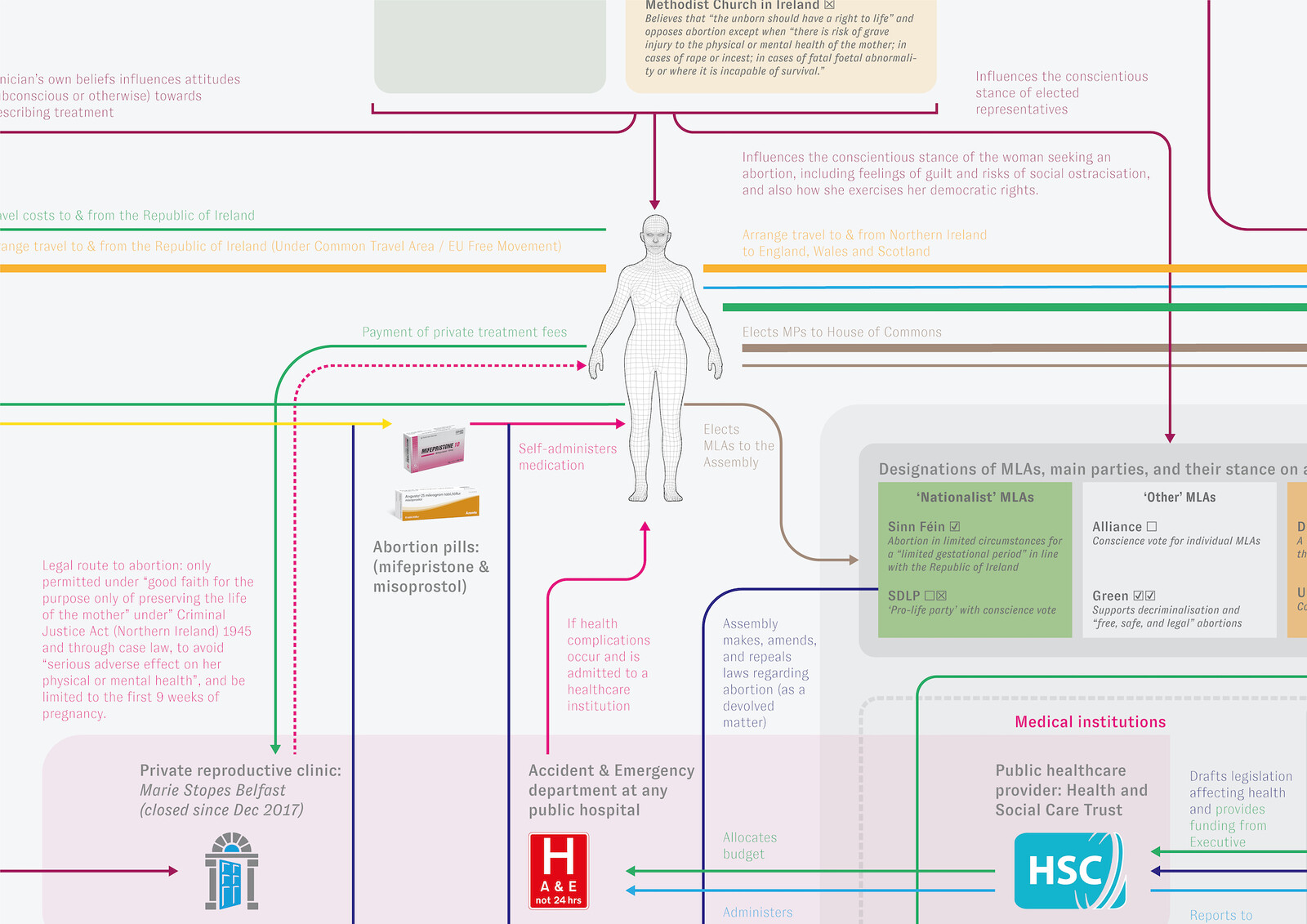

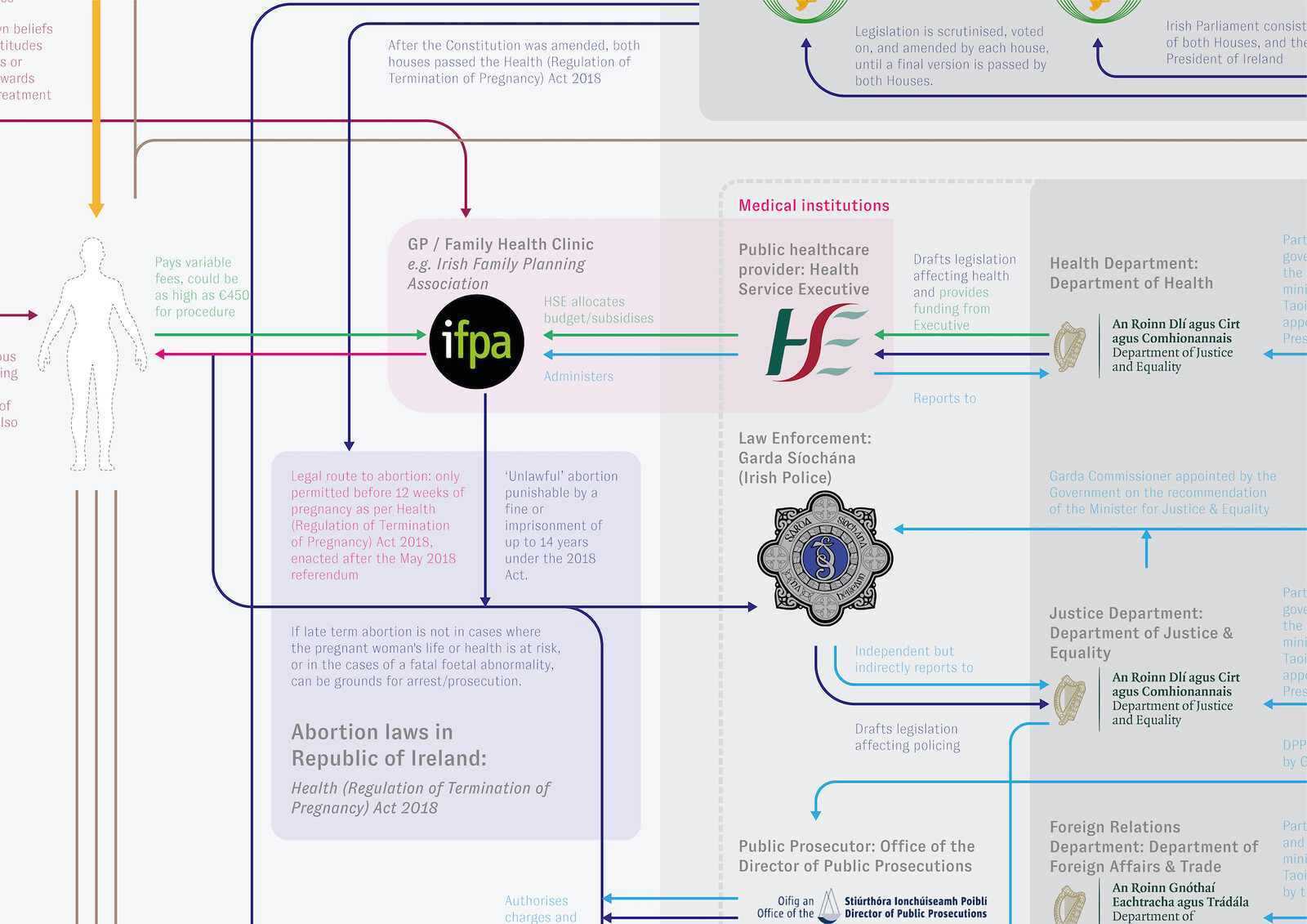

Counter-mapping the border for the child-bearing body: all the apparatuses of the state across the jurisdictions that exercise power over a Northern Irish woman’s journey of reclaiming her right to an abortion. Image by Calvin Po.

Counter-mapping the border for the child-bearing body: obtaining a legal abortion in Northern Ireland was highly restricted in almost all circumstances and not available on public healthcare. Image by Calvin Po.

Counter-mapping the border for the child-bearing body: despite recent legalization of abortion in the Republic of Ireland, it still has lower term limits than Great Britain (12 weeks instead of 24). Image by Calvin Po.

Counter-mapping the border for the child-bearing body: Northern Irish women seeking an abortion in England had to book through a special system and reclaim travel expenses afterwards. Image by Calvin Po.

Counter-mapping the border for the child-bearing body: all the apparatuses of the state across the jurisdictions that exercise power over a Northern Irish woman’s journey of reclaiming her right to an abortion. Image by Calvin Po.

The border in the child-bearing body

For a woman in Northern Ireland seeking an abortion, removing herself from its land and crossing a border—typically crossing the Irish Sea by ferry to Great Britain, where abortion was legalized in 1967—has long been the only viable option.12 The Republic of Ireland eventually legalized abortion after a constitutional referendum in 2018, and in 2019, legislative reforms were imposed on Northern Ireland. Up until then, Northern Ireland had some of the most punitive abortion laws in Europe: legal exception was only made for pregnancies that would threaten the mother’s life or have permanent and adverse effects on her physical or mental health. Abortion was criminalized even for fatal fetal anomaly, despite being ruled by the UK Supreme Court and the Northern Irish High Court to be in contravention of the European Convention on Human Rights.13

This system has been perversely sustained by the mechanisms of the Good Friday Agreement, where abortion law reform efforts in the Northern Irish Assembly have been threatened (regardless of majority support) with “petitions of concern,” a veto procedure originally introduced in Anglo-Irish negotiations to protect a minority community from majority rule.14 Though reproductive rights have since become more accessible on paper, they can be claimed only by navigating complex and contradictory systems, sustaining these bureaucracies as sources of violence towards women. 15 In April 2020, well after decriminalization, women in Northern Ireland were still told to take the ferry across the sea border to seek treatment in England amid the travel restrictions and flight cancelations of the COVID-19 lockdown.16

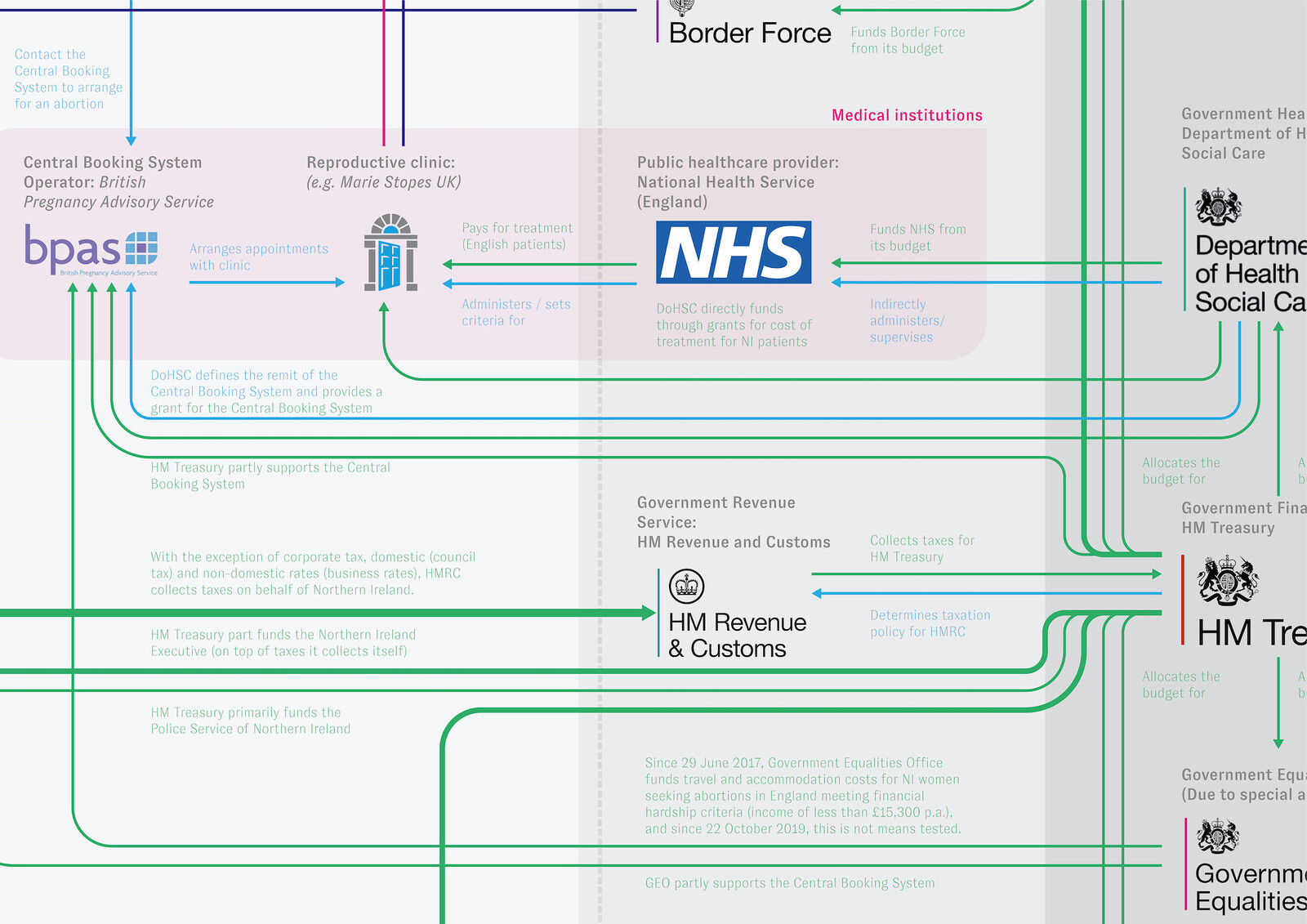

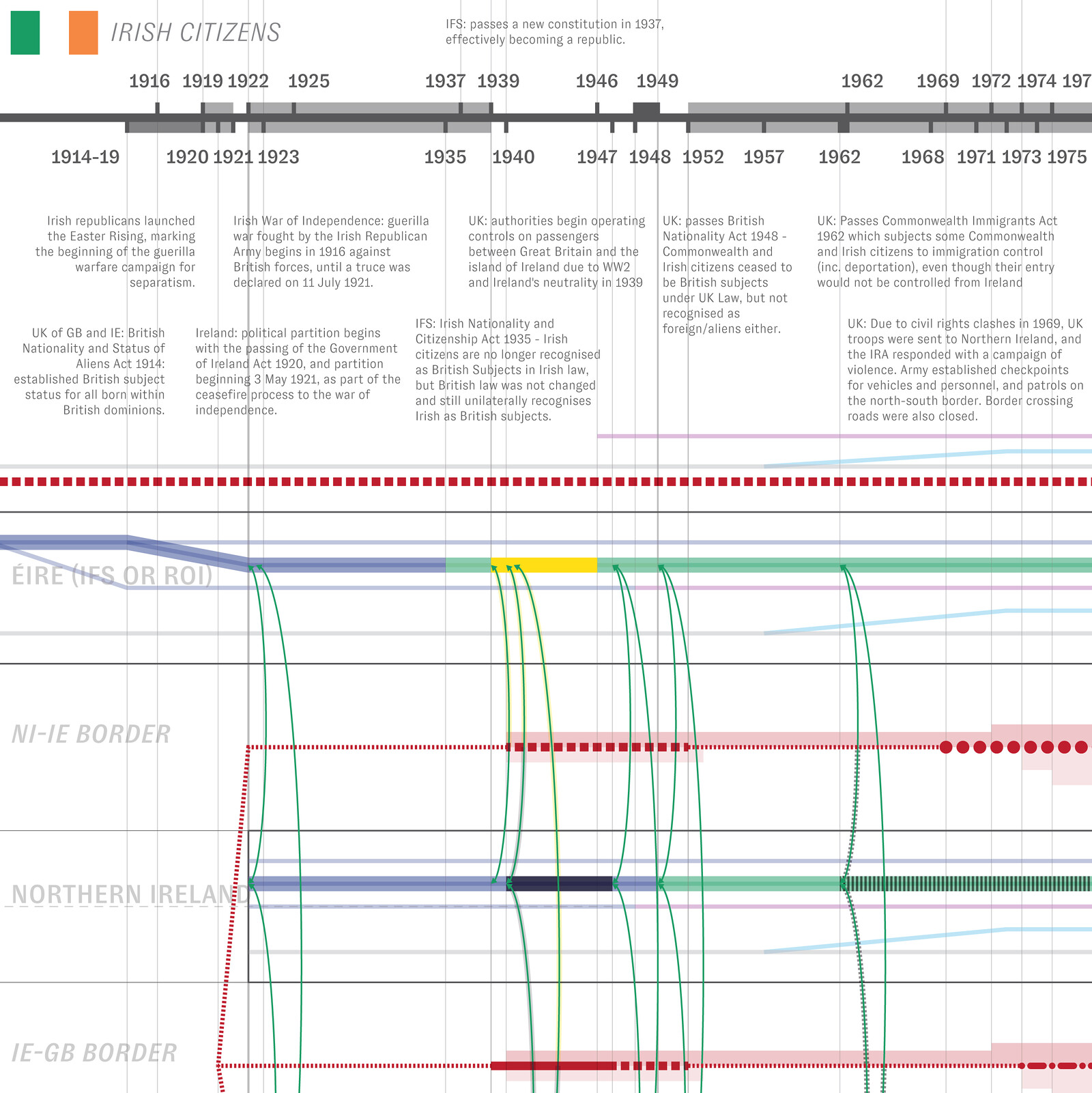

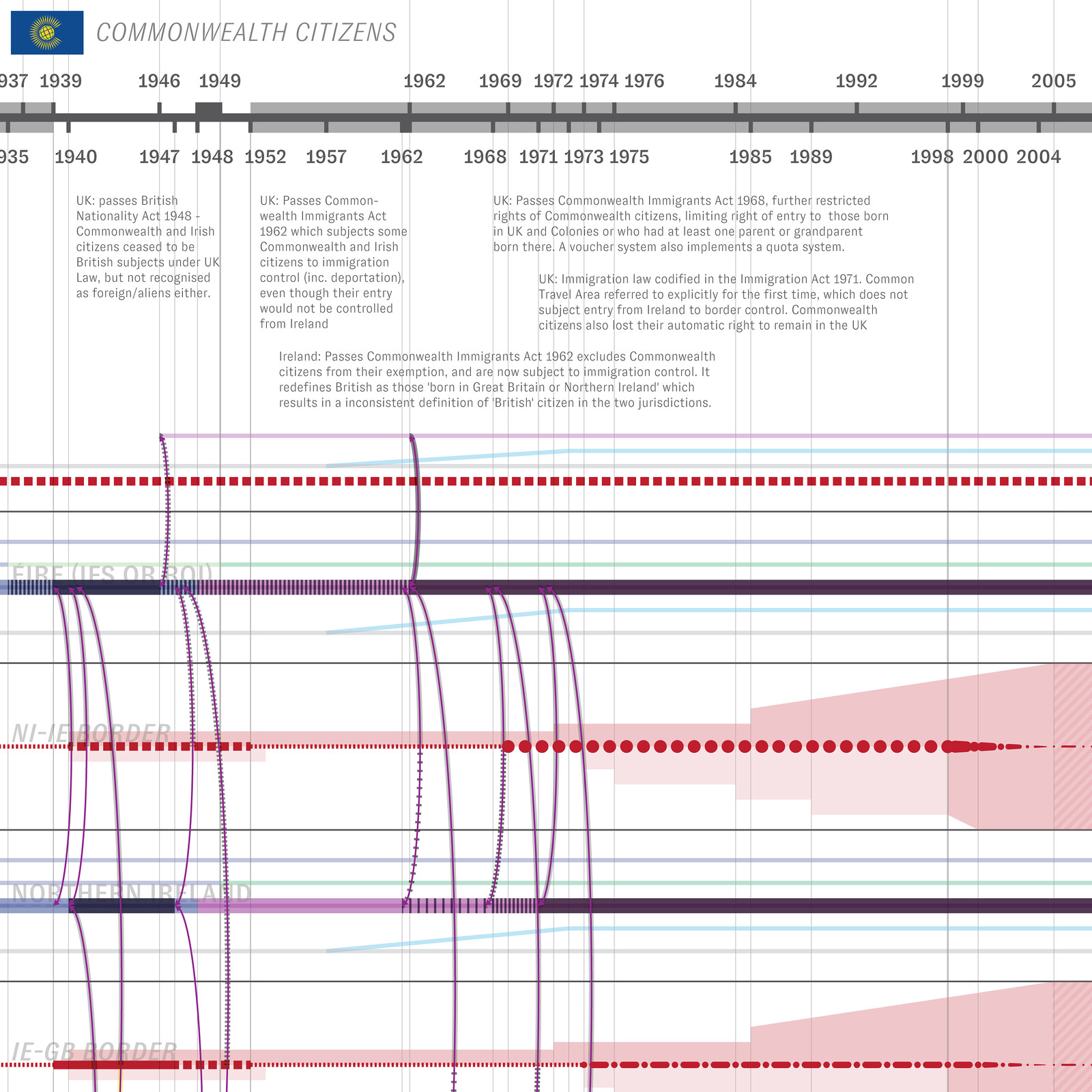

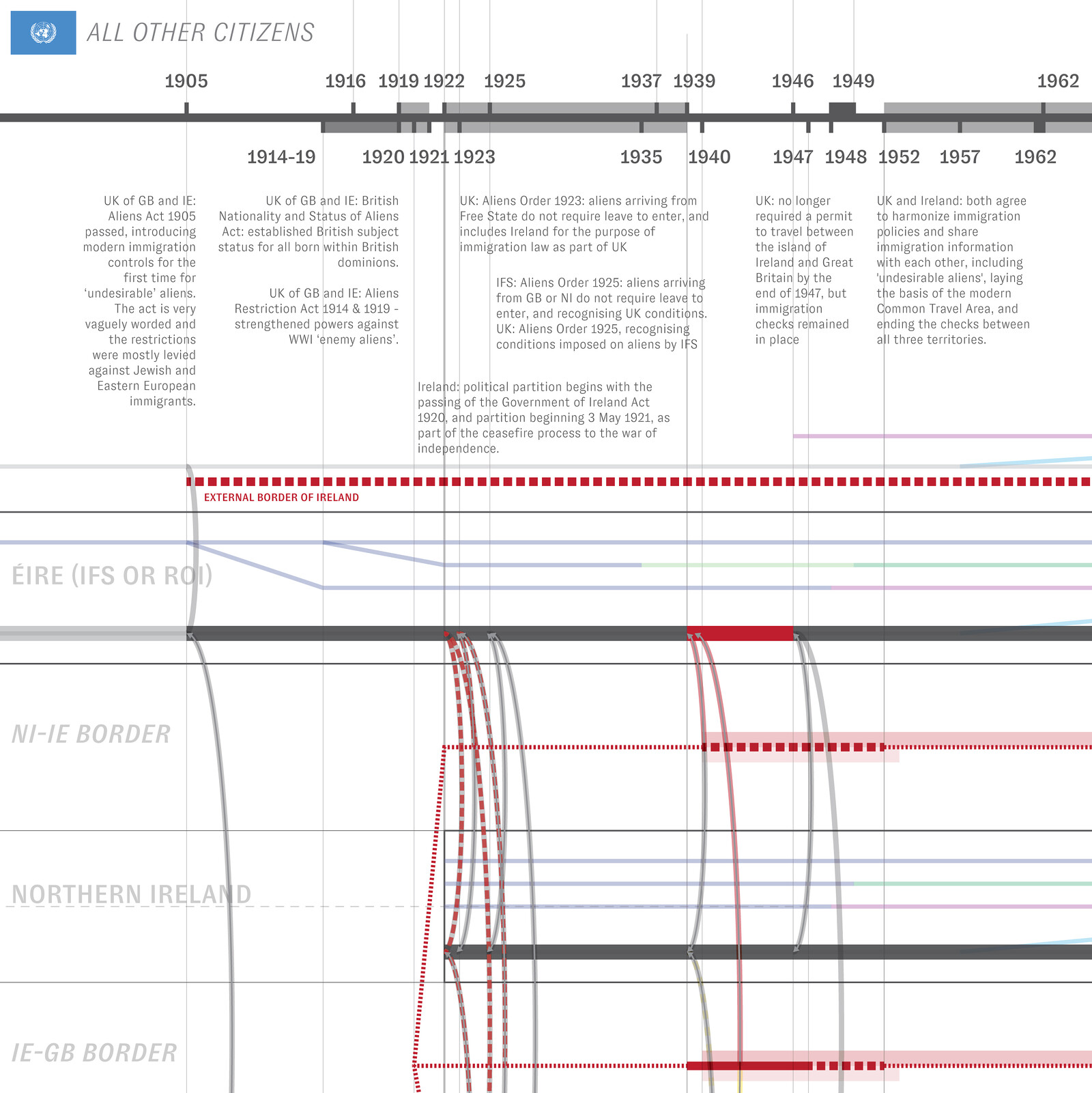

Counter-mapping the border for the migrant body: the “openness” of the borderless Common Travel Area evolved over time, and varies for different nationalities. Image by Calvin Po.

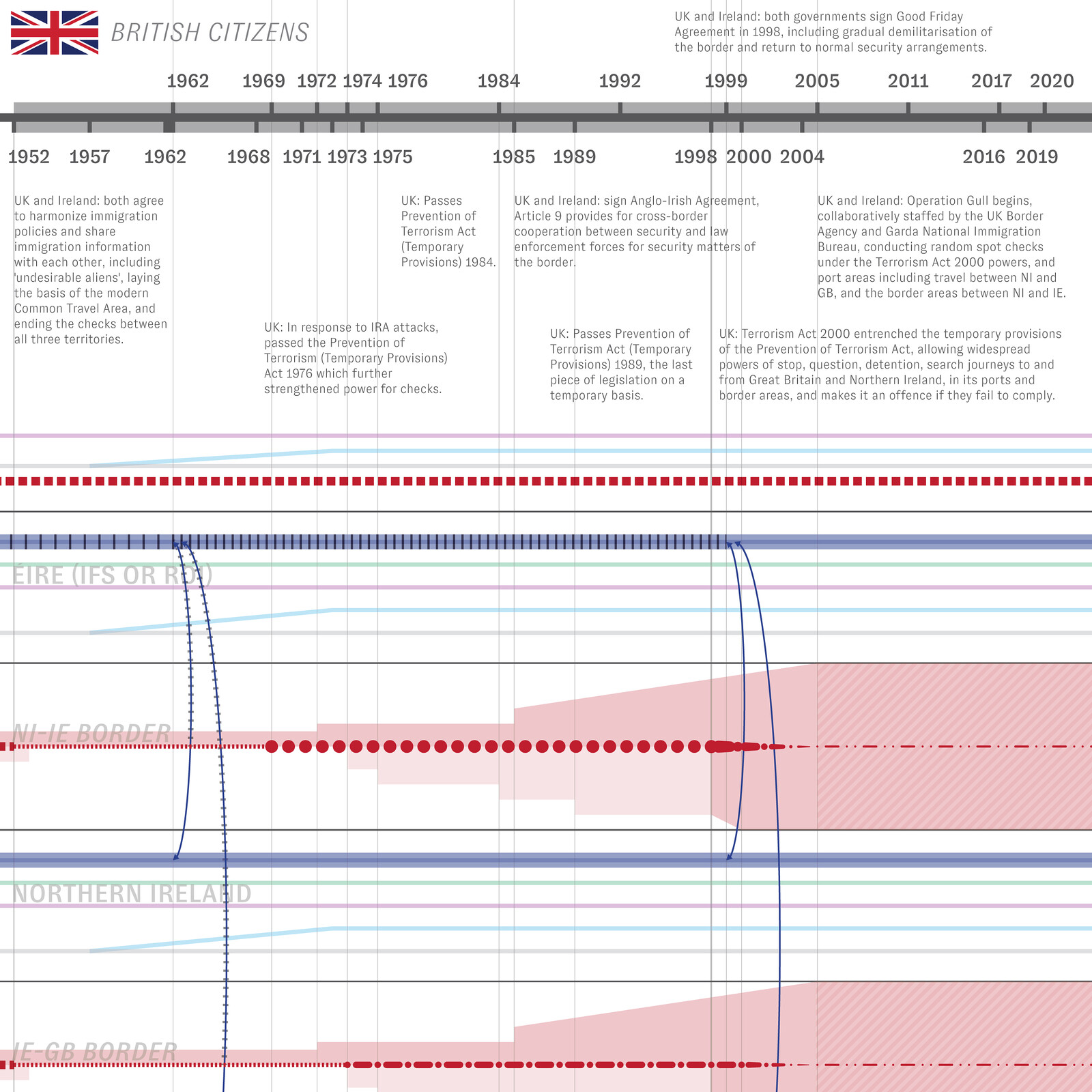

Counter-mapping the border for the migrant body: for the British citizen, the “open” border condition is governed through previously temporary anti-terrorism powers, which extend far beyond the border. Image by Calvin Po.

Counter-mapping the border for the migrant body: for the Irish citizen, their status evolved with independence from British subjects to migrants, subject to unilateral deportation from the UK. Image by Calvin Po.

Counter-mapping the border for the migrant body: for the Commonwealth citizen, their rights were gradually diminished from British subjects to migrants in the UK, and was followed by equivalent Irish policies to preserve the CTA. Image by Calvin Po.

Counter-mapping the border for the migrant body: for all other citizens, the “openness” of the border condition relies on the harmonization of immigration policies of both the UK and Ireland. Image by Calvin Po.

Counter-mapping the border for the migrant body: the “openness” of the borderless Common Travel Area evolved over time, and varies for different nationalities. Image by Calvin Po.

The border in the migrant body

The fertility and productivity of both the body and soil are deeply intertwined in the extractive colonial dynamics that define migration between Great Britain and Ireland.17 By the early-nineteenth century, the colonial confiscation and reform of land imposed by the migrant planters from Britain shifted the agricultural production by Ireland’s poor and dispossessed towards “cottier” farming on small, leftover plots, a subsistence practice highly dependent on seasonal migration for agricultural employment in Britain to pay land rents.18 The potato crop’s nutritiousness and ability to thrive on such small plots, in turn, revolutionized reproductive patterns where younger ages of marriage, higher fertility, and lower mortality drove further subdivision of family land among sons for potato farming.19 This catalyzed a precarious population explosion that was highly reliant on the potato crop, the staple food for three million out of Ireland’s peak population of 8.5 million on the eve of the Great Famine, and enabled the Famine’s apocalyptic depopulation when the potato crop failed.20

Much of the mass exodus of Ireland’s surviving labor force was again reaped by Britain in the first peak of Irish immigration during and after the famine years. This trend was sustained by post-Famine effects on family structures and marital fertility, where a stem family system of inheritance allowed only one son to inherit the unsubdivided farm, displacing the other descendants and encouraging their emigration.21 Even after Irish independence in 1922, “push” factors (the disruptive transition from British economic dependency and reduced labor demand with more productive agriculture) and “pull” factors (Britain’s demand for military, agricultural, and industrial labor in WW2 and beyond, and the post-war economic boom under a newly-established welfare state) all contributed to a second peak in Irish immigration to Britain post-WW2.22

This colonial legacy has shaped how modern immigration regimes have been constructed in the two states. Immigration controls within the British Isles have been minimal under the “open-border” Common Travel Area (CTA) since 1923 (almost as long as Irish independence), one rationale for which being to maintain the supply of Irish workers to Britain.23 Within the CTA, Ireland’s status as a former British colonial possession is still visible in the unequal rights of British and Irish citizens in each other’s territories: UK law still claims Irish bodies (and in fact Ireland itself), treating Republic of Ireland as “not a foreign country” for the purposes of any British law, and its citizens not “foreigners.”24 British citizens, conversely, are exempt from Irish immigration laws, and the UK still reserves the unilateral power to deport Irish citizens (even in Northern Ireland), despite few means to control their reentry across either border.25 Despite their entitlement under the Good Friday Agreement to either or both citizenships, people born in Northern Ireland can have their Irish citizenship ignored or stripped of their British citizenship at the Home Office’s discretion.26

The operation of the open-border area also required mutual enforcement of each state’s external immigration policy, but in effect, involved Ireland adopting British policy.27 In the late 1960s, this included an independent Ireland shadowing Britain’s gradual exclusion of Commonwealth immigrants after the racially-motivated backlash symbolized in Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech. To this day, the external migrant does not enjoy the same borderless travel in the CTA, subject to asynchronous visa policies and racial profiling.28

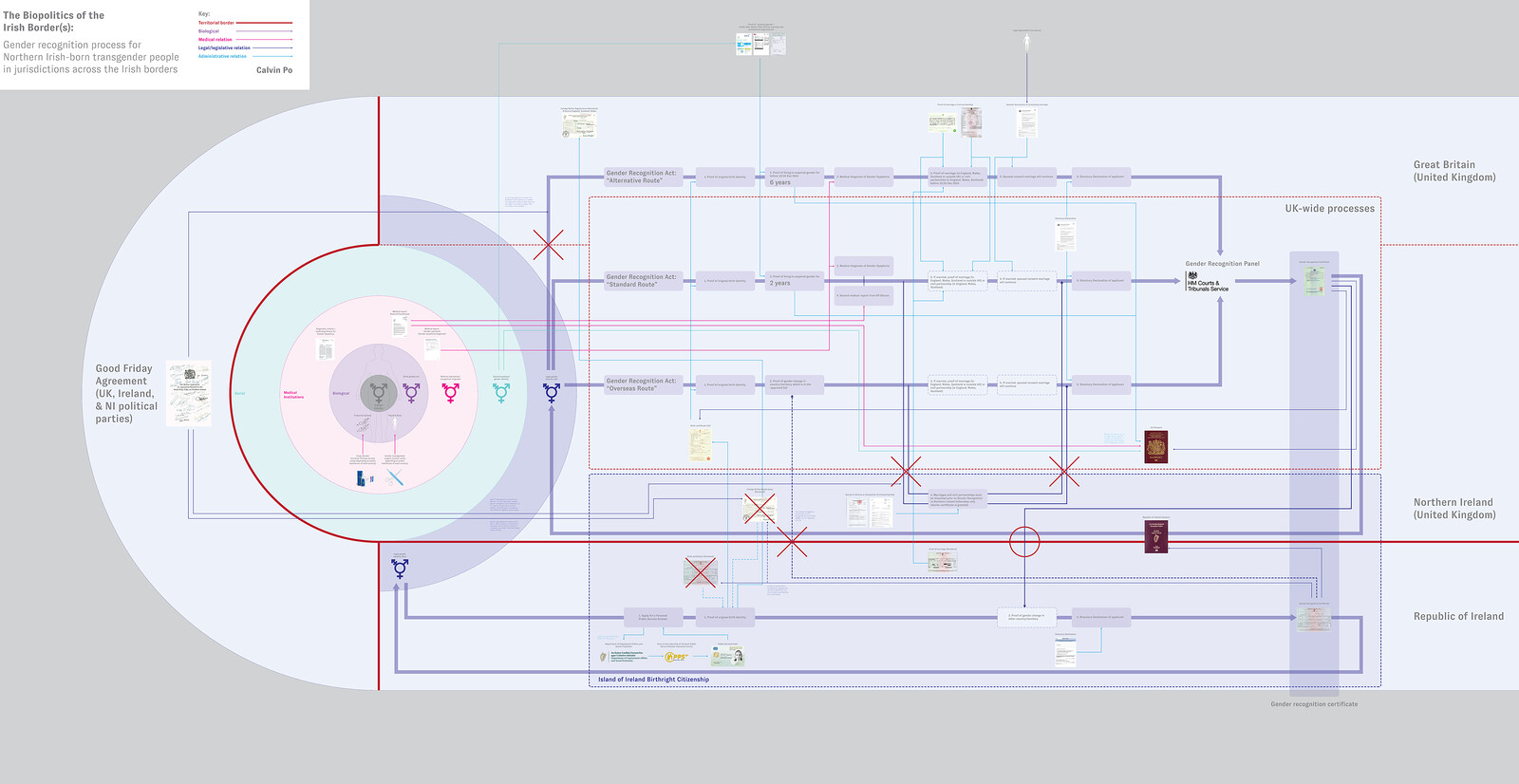

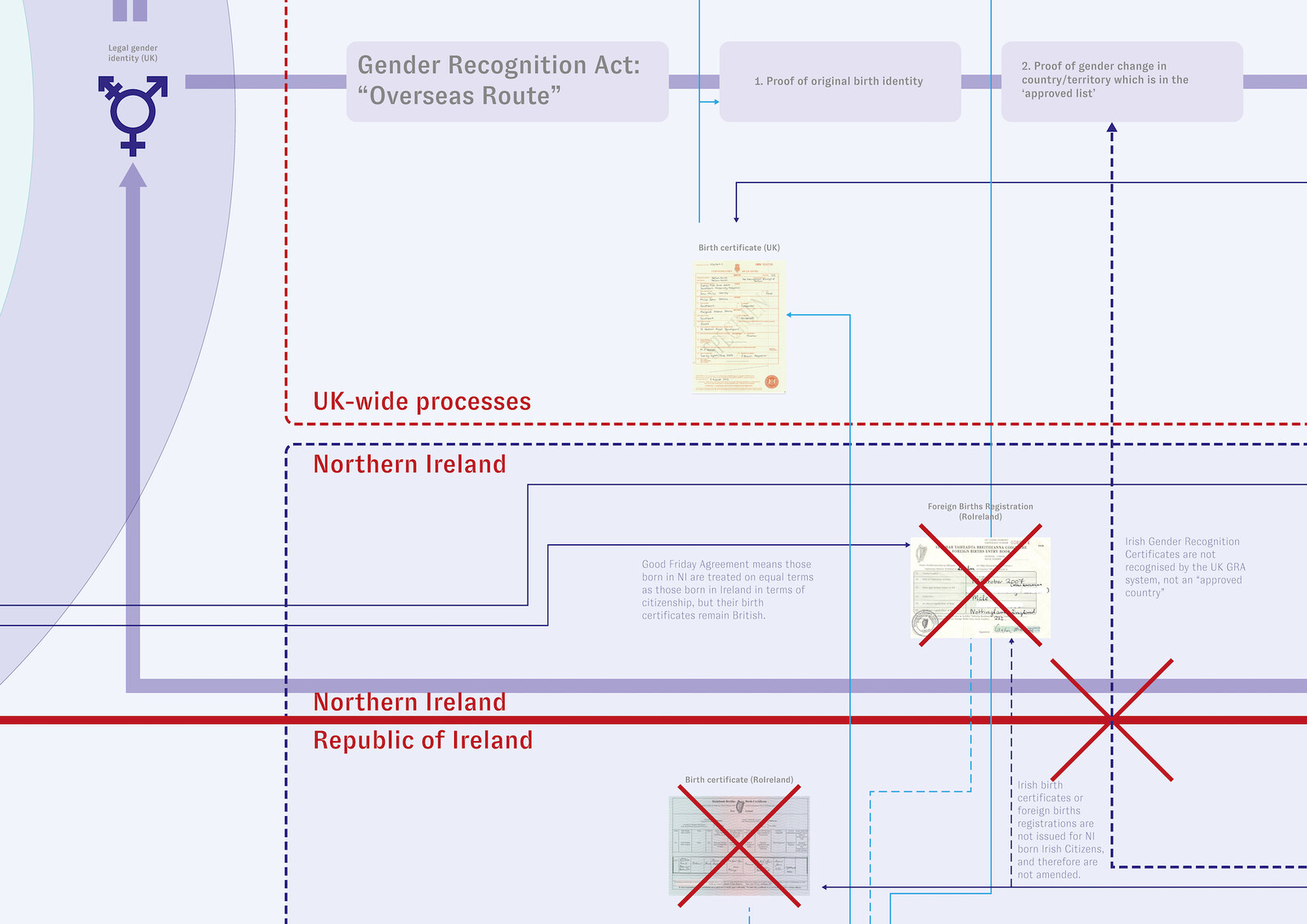

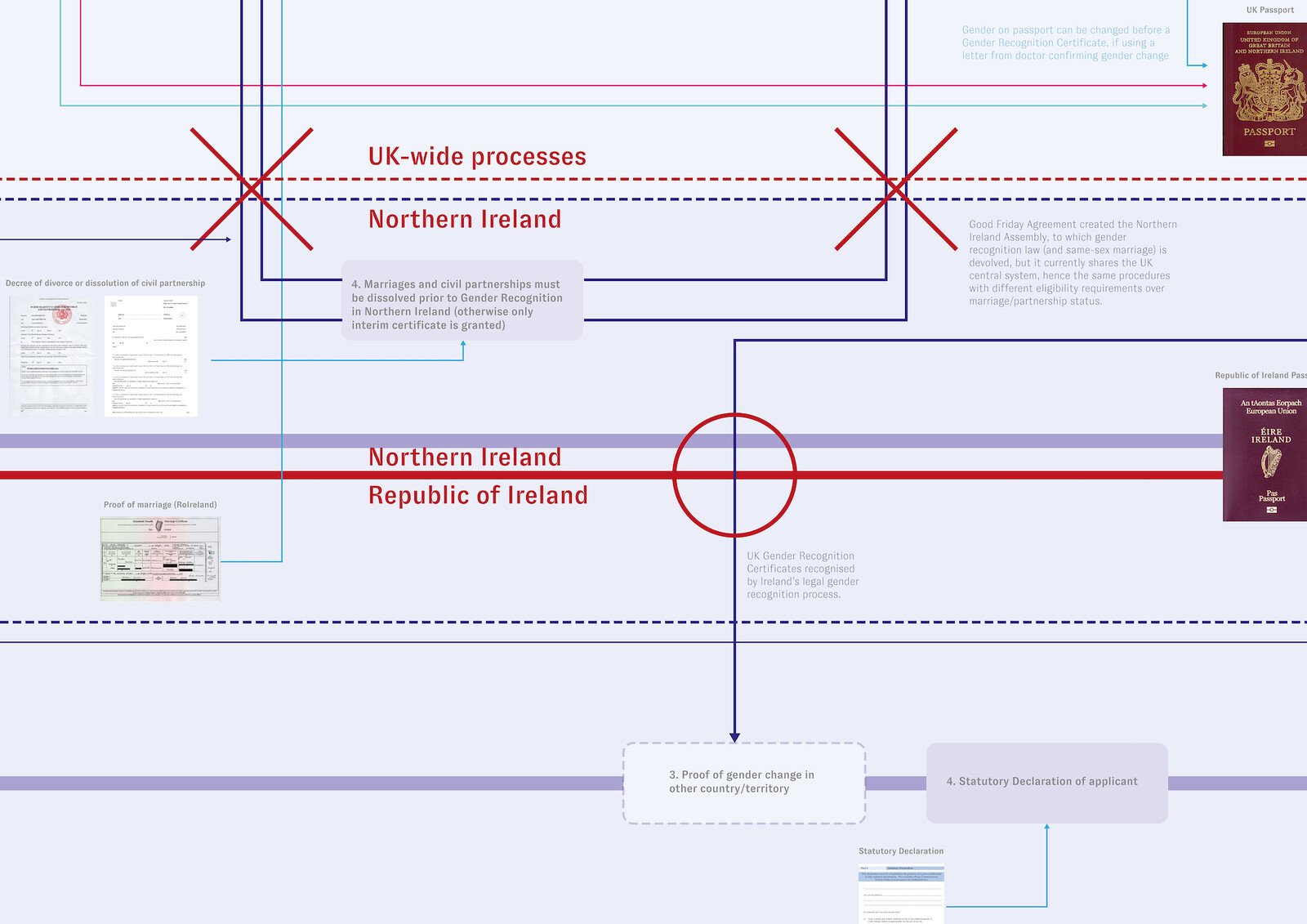

Counter-mapping the border for the transgender body: A system map of the three gender recognition processes, with hard borders running between their bureaucratic processes and paperwork. Image by Calvin Po.

Counter-mapping the border for the transgender body: Northern Irish dual citizens have British birth certificates, which cannot be amended by Ireland’s legal gender recognition process, and their Irish gender certificate is not recognised by the UK. Image by Calvin Po.

Counter-mapping the border for the transgender body: Northern Ireland’s ban on same-sex marriage until 2019 meant the UK’s legal gender recognition process required dissolution of unions for transgender people living in Northern Ireland. Image by Calvin Po.

Counter-mapping the border for the transgender body: A system map of the three gender recognition processes, with hard borders running between their bureaucratic processes and paperwork. Image by Calvin Po.

The border in the transgender body

The Good Friday Agreement enshrines Northern Irish people’s birthright to hold British or Irish citizenship, or both. A transgender dual citizen’s legal gender identity is therefore governed by both states. But these regimes of legal gender recognition are asynchronous and incompatible: the UK unilaterally does not recognize Ireland’s more liberal self-declaratory process of gender identification. The legal truth of the body’s gender(s) produced by the “law’s fictional technologies” of each jurisdiction, ceases to hold once the body leaves its territory, creating a border between a body’s legal gender identity/identities.29 Despite a Northern-Irish-born transgender person’s birthright to choose their citizenship, the legal proxies of their birth gender (their birth certificate) are under British jurisdiction alone.30 As a compromise, Article 2 of Ireland’s constitution, which formerly defined the nation territorially, was revised after the Good Friday Agreement to reframe the Irish nation as a collectivity of persons.31 A person born in Northern Ireland is not issued with Irish Foreign Birth Registration certificates (unlike foreign-born Irish citizens) that can be amended through Ireland’s own gender recognition process; only their Irish passport can be amended. Northern-Irish-born people are considered part of a reunited Ireland for citizenship purposes, but for residency they are not, and thus face obstacles in acquiring an identity number that acts as a proxy for a body’s interactions with the Irish state, including the legal gender recognition process.

The UK’s problematic gender recognition process is already fraught with its own bureaucratic violence, requiring intrusive medical examination and a perverse burden of “proof” for acquired gender, part of the state’s marginalization of deviance from the (re)productive paradigm through medical and psychiatric pathologization. But for a transgender body’s legal gender identity to cross the UK-Ireland border without obstruction, and with legal recognition of their acquired gender in their two countries of citizenship, they must undergo the bureaucratic processes twofold.

Despite the whole UK sharing one legal gender recognition process, crossing the sea border between Great Britain and Northern Ireland can entail a gain or loss of a transgender body’s rights. Same-sex marriage was unlawful in Northern Ireland’s jurisdiction until October 22, 2019, and opposite-sex civil partnerships were not possible until January 13, 2020. Until then, transgender people in Northern Ireland alone could not obtain a full Gender Recognition Certificate if they were married or in a civil partnership, and were required to dissolve their union to complete the process.

From soil to body politic(s)

The perennial tension between the land and body, and the state’s exploitation of both their fertility and productivity, can be traced throughout the story of the Irish borders, from colonization and partition to post-independence and post-conflict settlement. Culminating in “hard” borders in bodies marginalized by the state’s biopolitical, (re)productive paradigm, the presumed borderlessness of “peace” disguises a more violent status quo. In this light, the Red Hand of Ulster’s claim sealed by the moment of contact between the body and the land is not only one of fertile productive potential of land and labor, and of sovereignty, but a claim of subjecthood and of rights. The mythic race between individual bodies becomes a very real reproductive race between populations. Yet in the legend’s pyrrhic victory, it is only part of the body—the bloodied severed hand—that is able to make these claims; the rest of the body is never truly able to reunite with its hand, trapped in a state of liminality. Likewise, the marginalized body in Northern Ireland is never fully able to escape the pull of one biopolitical regime or another.

At its crux, the Good Friday Agreement recognized and attempted to patch over the absurdities in making sovereign soil the locus of a nation-state’s power. The messy, mobile, material reality of the deviant body upends the otherwise complacent simplicity of the map, the territory, and its paradigm of power. In a region that is charged with binaries of Unionist-Nationalist, Protestant-Catholic, British-Irish, majority-minority, territorial-extraterritorial, fertile-infertile, and productive-unproductive, the binary-breaking equivocality of the body remains the constant undertone of resistance.

Éamonn Ó Ciardha and Micheal Ó Siochrú, “A Laboratory for Empire,” History Ireland 17, no. 6 (2009): 10–11.

Settlements in Northern Ireland can be distinctly characterised as Protestant or Catholic by the majority community in their population. This was used to inform the creation of the border of Northern Ireland itself, which was established as a “Protestant-majority” polity.

Michael MacMahon, “Units of Land Measurement,” Clare County Library, February 28, 2003, ➝.

Conor Mulvagh, “How Was the Irish Border Drawn in the First Place?” The Irish Times, February 11, 2019, ➝.

In the context of Northern Ireland, the Protestant population corresponds loosely (though not necessarily) to a unionist political stance in favor of remaining part of the UK (unionism), and likewise the Catholic population loosely to a nationalist stance supporting Irish reunification (nationalism).

In Northern Ireland, the equivalent institutions are instead called Health & Social Care and Public Prosecution Service, which omit references to a nation or head of state.

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1973), 296.

See: Northern Ireland Office, “The Belfast Agreement,” Constitutional Issues, 1(ii), 1998; Ian Paisley, quoted in Cormac Ó Gráda and Brendan Walsh, “Fertility and Population in Ireland, North and South,” Population Studies 49, no. 2 (1995): 259.

Patrick McGregor and Patricia McKee, “Religion and Fertility in Contemporary Northern Ireland,” European Journal of Population/Revue Européenne de Démographie 32, no. 4 (2016): 618.

An ironic fate for a territory predicated on its population’s Protestant faith, but spatially fixed and inert in response to population changes. Paul Nolan, quoted in Gareth Gordon, “‘Catholic Majority Possible’ in NI by 2021,” BBC News, April 19, 2018, ➝.

After the Good Friday Agreement, bodies in Northern Ireland are subject to the influences of the governments of the UK and Republic of Ireland through its provisions for east-west cooperation. Many matters, including marriage, abortions, and legal gender recognition, are devolved by the UK to the jurisdiction of Northern Ireland’s own state institutions. Northern Ireland’s government in its own capacity also works with the Republic of Ireland on certain matters under north-south cooperation.

After crossing, her right to public healthcare was still determined by her territory of residence, making her (until recently) reliant on private funding for her treatment. The cost barriers of childcare, pay during work leave, and financial dependency remain unacknowledged. In 2017, judges on the UK’s Supreme Court narrowly rejected a case that would have entitled Northern Irish women to free abortions through the NHS in England; since then, England, Wales and Scotland have gradually offered NHS-funded abortions to women traveling from Northern Ireland, while treatment in the Republic of Ireland may carry fees, and only permits abortions up to 12 weeks (rather than 24 weeks in Great Britain). Amelia Gentleman, “Supreme Court Narrowly Rejects Northern Ireland Free Abortions Appeal,” The Guardian, June 14, 2017, ➝.

UK Supreme Court, “In the matter of an application by the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission for Judicial Review (Northern Ireland),” Reference by the Court Of Appeal in Northern Ireland Pursuant to Paragraph 33 of Schedule 10 to the Northern Ireland Act 1998 (Abortion) (Northern Ireland), 2018, UKSC 27, ➝; Rory Carroll, “Northern Ireland Abortion Law Ruled To Breach Human Rights,” The Guardian, October 3, 2019, ➝.

Gareth Cross, “DUP Will Use Veto To Block Abortion Rights In Northern Ireland Says Jim Wells,” The Belfast Telegraph, May 28, 2018, ➝. Under the Good Friday Agreement, legislators sitting in the Assembly must be designated as “unionist,” “nationalist,” or “other.”

One perverse consequence is that up until 2019, a woman’s taxes paid to the UK government were used to directly fund the Police Service of Northern Ireland that would have arrested her for unlawful termination, while simultaneously, through a loophole of the UK government’s Government Equalities Office, would have reimbursed her travel, accommodation and abortion cost elsewhere in the UK, all within the same state.

Amanda Ferguson, “Northern Irish Women Told to Sail to England for Abortions despite Pandemic,” Reuters, April 7, 2020, ➝.

Ireland served as Britain’s main migrant labor source from the 1800s until the 1950s, and this colonial dynamic of extraction, of both economic productivity and labor force, continues to shape the borders in the migrant body. Colonialism and Irish migration to Britain was notably used as an example by Marx to illustrate his law of capitalist accumulation in Chapter 25 of Capital, volume 1. See also: Sean Glynn, “Irish Immigration to Britain, 1911–1951: Patterns and Policy,” Irish Economic and Social History 8, no. 1 (1981): 50.

See: “Irish Famine: How Ulster Was Devastated by Its Impact,” BBC News, September 26, 2015, ➝; James H. Johnson, “Harvest Migration from Nineteenth-Century Ireland,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 41 (1967): 99.

Kenneth H. Connell, “The Potato in Ireland,” Past & Present 23 (1962): 57–71.

Phelim P. Boyle and Cormac Ó Gráda, “Fertility Trends, Excess Mortality, and the Great Irish Famine,” Demography 23, no. 4 (1986): 543.

See: Richard T. Schaefer, Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society (London: SAGE Publications, 2008), 205; Edward E. McKenna, “Marriage and Fertility in Postfamine Ireland: A Multivariate Analysis,” American Journal of Sociology 80, no. 3 (1974): 689.

See: Robert E. Kennedy, “Emigration and Agricultural Labor-Saving Techniques,” in The Irish: Emigration, Marriage, and Fertility (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), 86–109; Glynn, “Irish Immigration to Britain,” 69.

Bernard Ryan, “The Common Travel Area between Britain and Ireland,” Modern Law Review 64, no. 6 (2001): 870.

Under the 1949 Ireland Act, c. 41, s. 2(1).

British citizens in Ireland are exempt from immigration law and deportation, under the Aliens (Exemption) Order, 1999. PBC Deb (Immigration and Social Security Co-ordination (EU Withdrawal) Bill), c. 170, February 26, 2019.

Simon Carswell, “Explainer: What Is the Emma DeSouza Case about?” The Irish Times, October 15, 2019, ➝; Simon Cox, “Brexit and Irish citizens in the UK: How to safeguard the rights of Irish citizens in an uncertain future,” The Traveller Movement, December 2017, 15.

Ryan, “The Common Travel Area,” 858.

Some nationals (e.g. Emaswati, Namibian) may have visa-free access in only one country but not the other, and they risk committing an immigration offence when crossing the (uncontrolled) Irish borders. See Nazia Latif and Agnieszka Martynowicz, “Our Hidden Borders: The UK Border Agency’s Powers of Detention,” Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission, 2009, 62. ➝.

Paul Preciado, “My body doesn’t exist,” in Documenta 14 Reader (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2017), 124.

This is because the Agreement’s principle of consent recognizes the sovereignty of the UK over Northern Ireland as the status quo. See: Ellen Murray, “Re: Response to the public consultation on changes to the Gender Recognition Act in England and Wales,” TransgenderNI, October 15, 2018, 3, ➝.

“The national territory consists of the whole island of Ireland, its islands and the territorial seas.” Ireland, Constitution of Ireland, “The Nation,” Article 2, 1937 (until 1998). After the Good Friday Agreement, this was amended in 1999 to: “It is the entitlement and birthright of every person born in the island of Ireland, which includes its islands and seas, to be part of the Irish Nation. That is also the entitlement of all persons otherwise qualified in accordance with law to be citizens of Ireland. Furthermore, the Irish nation cherishes its special affinity with people of Irish ancestry living abroad who share its cultural identity and heritage.” Ireland, Constitution of Ireland, “The Nation,” Article 2, amended 1999.

Exhausted is a collaboration between SALT and e-flux Architecture, supported by L’internationale and the Prince Claus Fund.