For almost all of human history, reproduction was inexorable, unimpeded, and imperative, as well as socially and medically dangerous. Reproduction reflected and structured the viability of a geographical location for sustained human settlement. Reproduction was the most important factor defining a population’s ability to meet its labor and security needs. And reproduction structured the development of sexual, gender, and family norms, the contours of punishment, property, and power; the meaning of status and status differences, the preserve of religion. Reproduction occupied the space where all of these matters intersected, as human society depended on reproduction, and reproduction defined society.

As long as human societies have functioned, authorities have regarded reproductive female bodies as tools for shaping society in ways that fit leaders’ concepts about how power and other resources should be accrued and distributed. For millennia, women survived under this regime. Over time, enslaved women generally gave birth to the next generation of enslaved persons, providing the key mechanism for sustaining and extending the life of slavery regimes. Free women gave birth to free children, a process that defined both freedom and slavery. Women suffered community ostracism and worse as a consequence of sex, pregnancy, and maternity under unconventional conditions, including coercion. They died from pregnancy and childbirth; countless newborns did not survive.

The outcomes of sex, pregnancy, and maternity were matters that women exercised little to no control over. They lived under layers of authority that forbade them to legally control the circumstances of sexual intercourse and its consequences, as well as the conditions of pregnancy and maternity. Women frequently and surreptitiously improvised and experimented with methods to interrupt the inexorable connections between sex, pregnancy, and maternity. But before the nineteenth century, with urbanization and the invention of mass-producible substances appropriate for the manufacture of contraceptives such as the male “sheath,” improvisation and experimentation were by definition unpredictable, and also, in most societies, elusive, illegal, blasphemous, or all three. The consequences for women were civic degradation and domestic subordination, as a matter of religious dicta, civic codes, and family norms.

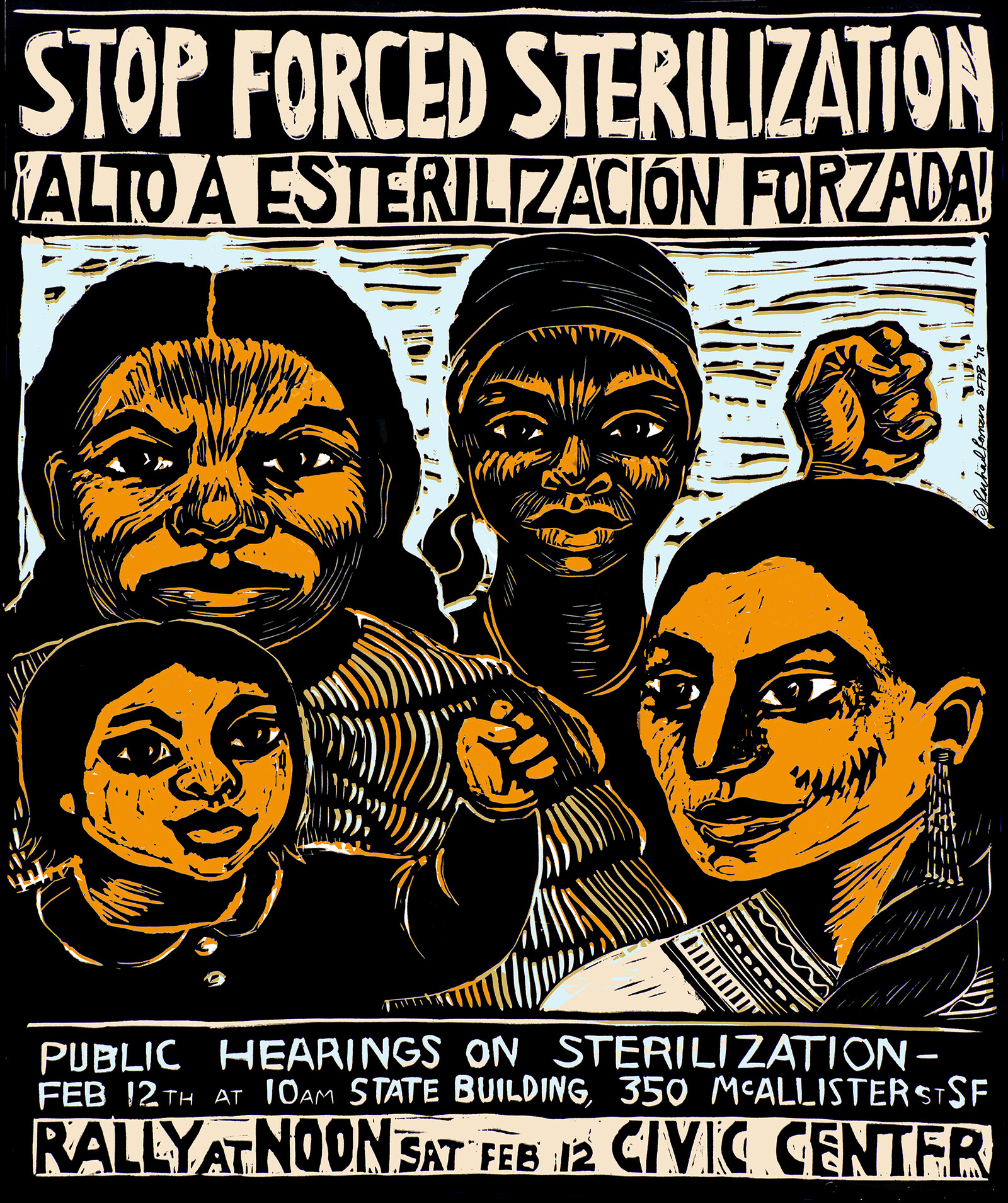

In the United States (and elsewhere), beginning in the mid-twentieth century, ideas and ideologies about female heterosexual sex, fertility, and reproduction were reborn. It’s not that the United States had previously eschewed white supremacist language, politics, and policies regarding “fit” reproduction and “fit” reproducers. The founders’ nationalist ambition to people the continent, the centuries-long commitment to the enslavement of Africans, the decimation of Native Americans, and the determination among white leaders to build and preserve a white, Christian country, created successive, robust, racialized population regime. But in the 1960s, we see the beginnings of a new regime. Many white people hated or were deeply uncomfortable with the outcomes of the Civil Rights Movement, and deployed racialized ideas about legitimate and illegitimate motherhood to express their resentments. At the same time, African Americans, Latinas, Native Americans, and other people of color brought bold claims about these matters into the public realm, forcing the country to hear new analyses that explained the relationship between contemporary, forced sterilization and slavery, and plumbed the relationship between citizenship and bodily integrity.

In the final third of the twentieth century, new technologies, white supremacy, and feminism all valorized reproductive individualism in the US, centering a racialized concept of “individual choice.” With the advent of the birth control pill and then legal abortion, politicians, policymakers, feminists, and others defined the reproductive consequences of heterosexual sex in marketplace terms: as the “choice” of the individual woman, who could choose, or not, to purchase and use anti-natalist materials (contraception) or procedures (abortion) to forestall conception and birth. The new dicta proclaimed that getting pregnant, and becoming a mother, was her choice, her legal and rightly choice.

Defining all women as choicemakers in the marketplace of reproductive options seemed to disassociate reproduction from demographic, economic, environmental, and racial matters, as well as politics. Starting in the 1980s, public-policymakers and politicians targeted the many aspects of society and of women’s lives (housing, welfare, education, and public health policy and settings, for example) that they deemed legitimate locations for erecting barriers to the choicemaking of certain women, whittling and qualifying the roster of females who could be designated “free” in the marketplace of reproduction. At the same time, they validated, and sometimes enlarged the reproductive freedom of those who had the wherewithal to enter into the consumerist arena where “choices” were considered appropriate.

In this era, public policy promoted measures that divided girls and women into good choicemakers and bad ones, using race and class as key markers. The public ideology of individualism and public slogans championing individual choice gave cover to a white public that did not wish to vocalize racial distinctions. “Choice” did not interfere with this white public’s naturalized commitment to the position that “poor women have no business becoming mothers.” And despite the fact that the birth control pill and legal abortion were introduced as triumphs of reproductive individualism and choice, by law, both required women to submit to the authority—to seek the permission of—a white, male-dominated medical profession that was largely disinterested in or hostile to these new opportunities for female self-management and reproductive dignity.

In these years, politicians, policymakers, and public health facilities pressed Black and Brown women to accept their new duty to control, constrain, and terminate reproduction. At the same time, white women assertively defined themselves as imbued with a new right to sexual and reproductive freedom. This distinction persisted. In 2017, for example, Tennesee Judge Sam Benningfield offered to reduce the sentence for any woman who accepted a hormone implant. At that time, Black people constituted 18% of the state’s residents but 36% of the people in jail and 42% of people in prison. In addition, the number of women in jail had risen 1,431% since 1980, and the number in prison 796%.1 Judges thus might sentence a woman of color convicted of petty crimes to a prescription for the birth control pill, or later, a contraceptive inoculation, in lieu of sentencing her to prison, and even might deny her public assistance because, while poor, she made the “bad choice” to become a mother. At the same time, the media valorized white girls and women for using their new reproductive choices to underwrite participation in the colorful, exciting “sexual revolution,” and for their responsible use of The Pill and legal abortion. White women were praised for translating “choice” into educational training and professional careers uninterrupted by unexpected pregnancy, as well as constraining childbearing in order to maximize the comforts and joys of the carefully curated middle-class family. The Black woman, on the other hand, remained enmired, officially marked as a member of a problematic “population” via her sexuality and reproductive life.

These updated, racialized distinctions were key to defining “race” in the United States. White females accrued value that depended on racially ascribed sexual and reproductive definitions; women of color, by definition, lacked this value. Naturally, the “value” of the children born to white women followed the value assigned to and assumed by their white mothers, and the “valuelessness” of the children of color reflected and perpetuated their degraded “race.” These features of mid-to-late twentieth-century reproductive politics were consistent with and supported a resurgence of anti-immigrant sentiment among white people. Since 1965, politicians have been consistently unwilling to extend the program of immigrant reform policies initiated by the Immigration and Naturalization Act passed in that year.

Toward the end of the twentieth century new, restrictive federal and state laws, funding cuts, and Supreme Court and lower court decisions have hindered women’s access to contraception and abortion. This, combined with widespread white hostility to funding the kinds of public services that all families require, has left reproductive rights and family supports in tatters. And as usual, when rights and freedoms are eroded in the US, the first and most severely affected are those with fewer resources and options: women of color, poor women, and their children. Expressing profound frustration with endless compromises, the erosion of established rights, robust, virulent Republican opposition to women’s rights and full citizenship status, a group of African American activists articulated the Reproductive Justice framework and launched the Reproductive Justice movement in 1994. The framework recognized that “choice” hadn’t lifted up women as a class. “Reproductive rights” and “choice” had not promoted safe, dignified reproductive individualism. Rather, these claims had sustained old—and stimulated new—expressions of white supremacy, population-control policies, and violent, crabbed religion in the public sphere.

According to the Reproductive Justice framework, reproductive dignity and safety can never be defined or achieved by focusing exclusively on the “right” or the “choice” not to get pregnant, not to stay pregnant, not to be a mother. This focus on avoiding conception and reproduction had, of course, been the focus of the white, feminist-led reproductive freedom movement, from the 1960s forward. But within the Reproductive Justice framework, an adequate understanding of reproductive rights, or reproductive justice, has to embrace the right to reproduce as explicitly and tightly as the right to refrain from reproducing. The Reproductive Justice movement speaks about the right to parenthood for millions whose human right to have children and to raise them had been historically brutalized during the slavery regime and its long aftermath. This claim is crucial because many women’s identities as persons, under white supremacy, had necessarily been constructed as lacking the qualities and rights of white parents. Destroying white supremacy requires reproductive justice. Reproductive justice cannot be achieved in the context of white supremacy.

The Reproductive Justice framework further explains that in itself, possessing the human right to reproduce or not is insufficient. Even when one adds the indispensable right to raise one’s children, in order to reproduce with dignity and safety, one needs the wherewithal to do so. How, for instance, can anyone safely reproduce and then raise a child with dignity and safety in a neighborhood near a seeping toxic dump, with underfunded educational institutions and poor medical facilities, inadequate and dangerous housing, and no grocery stores? (What does “choice” mean in this context?) How can a child be safely raised in a white-supremacist environment? How can the decision to have a child be made freely and safely if the potential parent knows that the environmental conditions into which the child will be born will harm the parent, the child, and their community? Reproductive Justice requires and depends on a person’s access to the resources necessary to raise a child. Without those resources, white supremacy and other toxicities flourish.

The Reproductive Justice framework and movement was the brainchildren of African American activists, but its vision lifts up everyone, mapping out the conditions of both reproduction and justice that communities and societies can depend on for decency and can embrace to achieve the conditions for fairness and full citizenship. Reproductive Justice has reshaped aspects of reproductive politics in the United States. Most legacy reproductive rights organizations have adopted the term, replacing 1970s-era language of “rights” and “choice.” Many US organizations, service providers, politicians, activists, and others have articulated and pursued reproductive-justice inflected goals, strategies, and programs. Reproductive Justice has deeply marked many contemporary working definitions of women’s health, community health, human rights, and citizenship. But still, in the third decade of the twenty-first century, the United States still largely operates under the model of the individualistic, reproductive health marketplace, one that only serves consumers/citizens who possess “adequate” resources.

There are still persistent, dramatic racial disparities in rates of maternal and infant mortality. Women of color are two to three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women.2 This phenomenon is not simply a matter of lack of money to pay for medical care, because the disparity occurs across class. The pregnancy-related mortality rate for Black women with a college degree is about five times that of similarly educated white women.3 Experts have identified implicit bias in healthcare—the persistence of white supremacy—as a key factor in structuring patient-provider interactions and health outcomes. The US Center for Disease Control and Prevention states that “the majority of [these] deaths—60% or more—could have been prevented” by addressing the causes of racially disparate pregnancy-related deaths. The rate of infant death per one thousand live Non-Hispanic Black babies before the first birthday is 10.8%, while for Non-Hispanic White babies it is only 4.6%.4

Trump-era attacks on the provision of reproductive healthcare to low-income people, including support for contraception and abortion, meant that girls and women lost access to care that had only rarely been sufficient in the past. Policies, practices, and slashed government support limited an individual’s range of choices, exposed provider bias as well as the effects of inequitable health insurance coverage, and reduced the provision of evidence-based standards of care.5 Reproductive health burdens were particularly harsh for immigrants whose access to services have diminished dramatically in recent years.6 No progress was made in broadening access to sexual and reproductive healthcare for other reviled members of society, including people with disabilities, young people living in foster care, incarcerated people, and the unhoused.

Covid-19 further exposed the ways that white supremacy disproportionately ruins the health and threatens the communities of people of color, endangering reproductive health and reproductive outcomes. In New York City, for example, Black people constitute 14% of the population and 23% of deaths from the virus. In Washington DC, the percentages are 45% and 76%, respectively. National, regional, and local analyses show that Black and Hispanic people have been receiving smaller shares of the vaccination relative to their share of total infections and deaths. The impacts of Covid-19 promise both short- and long-term negative health consequences in these communities as well as a greater need for supports for reproductive health, family well-being, and community viability.

Reproductive Justice lays out the conditions for reproductive dignity and safety for all reproducing persons, their families, and communities. The process of building a broad political embrace of its vision and institutionalizing its precepts will be long and arduous, in the United States and around the world. Nothing less than Reproductive Justice (and its adaptations) will lay the ground for decoupling reproductive bodies from the brutality of shifting political programs, including religious, white-supremacist, nationalistic, misogynist, anti-immigrant, neoliberal agendas. Only Reproductive Justice allows us to imagine and act in the name of the reproducing person as someone who is living in community with human rights.

“Racial and Ethnic Disparities Continue in Pregnancy-Related Deaths,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, September 5, 2019, ➝.

“Infographic: Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pregnancy-Related Deaths—United States, 2007–2016,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ➝.

“Infant Mortality,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ➝.

Osub Ahmed, Shilpa Phadke, and Diana Boesch, “Women Have Paid the Price for Trump’s Regulatory Agenda,” Center for American Progress, September 10, 2020, ➝.

Nuestro Texas, ➝.

Exhausted is a collaboration between SALT and e-flux Architecture, supported by L’internationale and the Prince Claus Fund.