I began writing this essay weeks before I left South Africa in November 2019 for good; picked it up again a week after my arrival in New York City and finished it in the midst of the global COVID-19 pandemic, which has forced the issue of “educational space” onto the agenda in ways no one could have predicted.

It’s no use going back to yesterday, because I was a different person then.

—Lewis Carroll1

Yesteryear

The start of the new academic year is always fraught, no matter where you are in the world. Aside from the usual logistical issues (enrolment numbers, fees, readiness of facilities or the adjuncts who got a better offer elsewhere), there are also deeper questions to be asked about the nature and direction of pedagogy: how is this year’s curriculum different from last? In what way are today’s students different from students of the previous decade? What skills and tools do they require in order to face the world? Which world? Whose world(s)? As the number of people enrolled in tertiary education continues to explode and economies slide in and out of recession, the question of what are we training students for is a constant thorn in the academy’s side.

In societies undergoing extreme and rapid changes—whether as a result of political, economic or environmental turmoil—this usual chaos is exacerbated as academic institutions struggle to reconcile two contradictory speeds: that of the world outside, often unraveling before everyone’s eyes, and the slower, incremental speed at which knowledge is generally built, one painstaking experiment after another, one publication at a time.

#RhodesMustFall protest at the University of Cape Town, South Africa.

The Graduate School of Architecture (GSA) was founded on the back of the existing Master’s program at the University of Johannesburg in an extraordinary moment of political crisis brought about by two large-scale student protests. #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall unfolded over several months in 2015 and 2016 and forced the words “decolonization” and “transformation” onto the national consciousness in a society that has always struggled to define itself. Modern? Colonial? Postcolonial? African? South Africa is—bafflingly—all and none of these. Twenty-five years on from the first democratic elections in the country’s history, South Africans are still coming to terms with how they describe themselves, both to each other and to the outside world. In a society still bitterly and intractably divided along race and class lines, it’s worth remembering that the spaces of education designed for apartheid-era white students were eventually opened to include all South African students, mostly by force.

The Bernard & Anne Spitzer School of Architecture at The City College of New York (Spitzer) has a different pedigree and history. Founded in 1969, it is New York City’s first accredited public school of architecture, opening doors to thousands of mostly local (NYC) students, many of whom are first-generation immigrants, recently-arrived newcomers to the United States and DACA students,2 whose ambiguous status is now pending after President Trump rescinded the policy in 2017. This potent mixture of cultures, languages, ancestry, and experiences of Spitzer’s students is both unique and under-explored.

Decolonize! Transform!

It is now five years since #RhodesMustFall began on March 9, 2015. The campaign was initially directed at the statue of Cecil John Rhodes outside the University of Cape Town, but protests quickly spread to other university campuses across the country, sharply dividing public opinion. A month later, the University’s Council voted at night to remove the statue, and on April 9, 2015, Rhodes was hauled off.

While the students’ anger initially appeared to be directed towards the statue, the underlying issues were much more profound. Within days, they began demanding real, deep curriculum changes across all subjects and disciplines. Put simply, they were fed up waiting for the promise of change from an almost exclusively Western, Eurocentric pedagogy to a canon that openly acknowledged, celebrated and explored “other,” non-European histories, experiences, and ways of understanding the world. Those changes, implied if not enacted since South Africa’s momentous move to democracy in 1994, simply had not arrived. A second protest movement, #FeesMustFall, erupted six months later, ostensibly centered on the cost of tertiary education, which effectively excluded poor black students from the academy, opened the same, ugly wound. Class and race, inextricably linked for the past 300 years in the South African psyche and culture, were shown to still be linked, twenty-four years after universal suffrage was finally attained.

Over the past year, however, despite having operated largely from within the internal, somewhat myopic bubble of South Africa’s rocky road to democracy, it has been something of a surprise to me to find the phrase “decolonizing the curriculum” everywhere, not just within South Africa. In conferences from Zagreb to Zürich, the question of what such a decolonized and/or transformed curriculum might look like, what it would feature, and how it might be taught have been discussed, argued over, defended, and explored over and over again. In an opinion piece in Metropolis magazine, the writer and historian, Mario Carpo notes, “the problem is that, once the Western architectural canon has been thrown overboard, together with its now unpalatable ideological ballast, nobody seems to know what else should replace it.”3

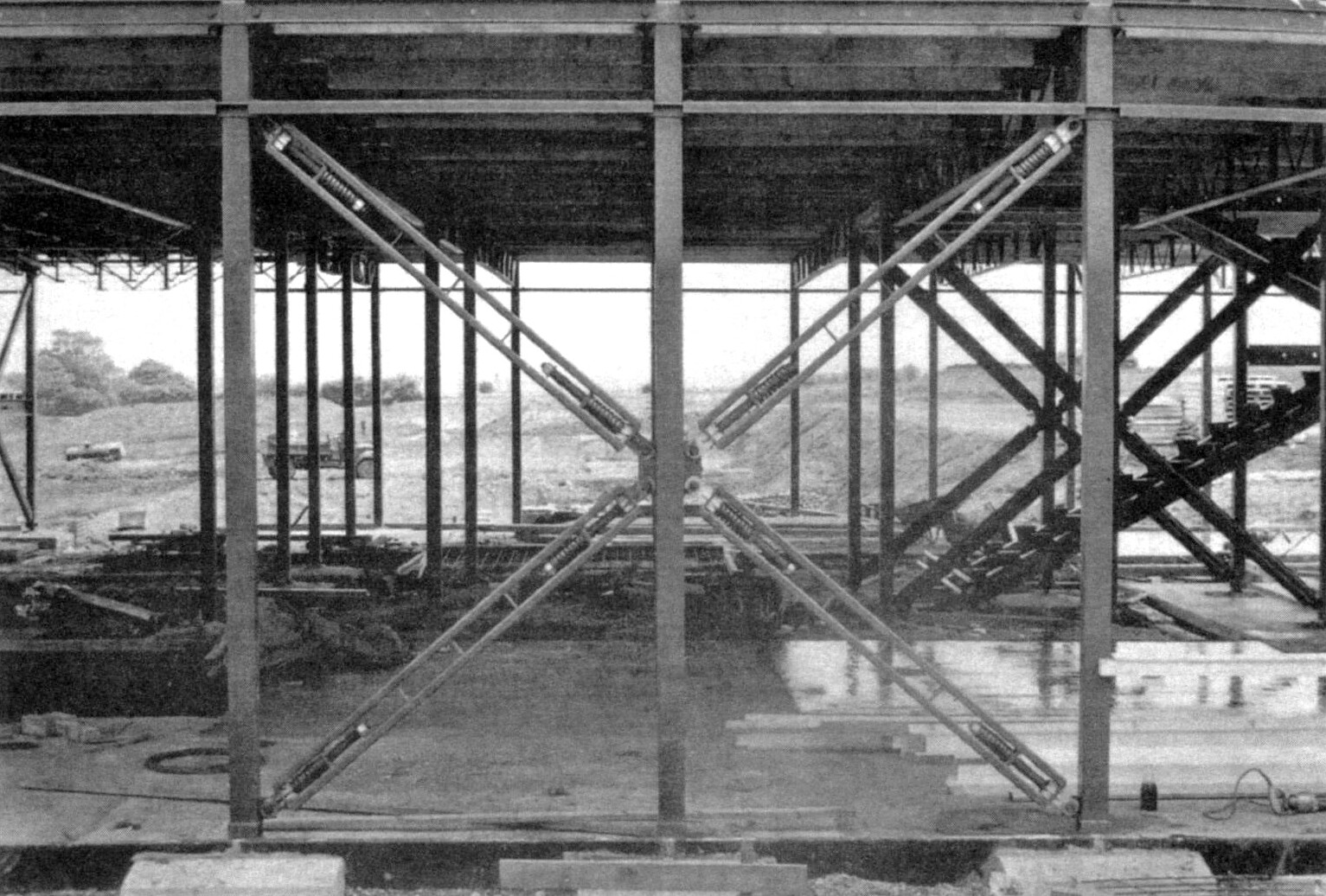

Having started, led, and left the GSA to take up the role as Dean of Spitzer, it comes to me slowly—and not without a twinge of sadness—that a departure is as good a moment as any to reflect on the experiment and experience of pedagogical decolonization. It’s complex, messy stuff, this question of how to undo several centuries’ worth of canon and replace it in time to meet the start of classes. Change requires more than protest, political expediency, or even anger. For real, lasting change to occur, the infrastructure of education must also change, and with it, its architecture, the physical spaces in which instruction takes place.

For most schools of architecture, those physical spaces follow roughly the same pattern—auditoria, lecture halls, classrooms, studios and workshops (and more recently, “fabrication” laboratories, or Fab Labs). In thinking about the ways such spaces might be “decolonized” or “transformed,” the workshop provides an interesting model. As Richard Sennett discusses in The Craftsman, workshops have always been models for sustained cooperation. In both ancient China and Greece, the workshop was one of the most important institutions, anchoring civic life and practicing the division of labor to a far greater degree than farming. Labor was often joined to family value through generations: sons of potters became potters; the daughters of weavers became weavers themselves, and so on. It strengthened the idea that the objects men make cannot be taken from them arbitrarily. It also allowed a certain amount of political autonomy, since most craftsmen were left alone to make their own decisions about how best to practice their craft. As sites of culture as well as production, workshops developed shared social rituals: honor-bound apprentice codes and public oaths of mutual obligation.

Dr. Huda Tayob’s History & Theory Colloquium at the GSA, held in the street, 2019. Photo: Counterspace.

After the American Civil War, freed slaves found themselves in almost exactly the same position as many South Africans today: impoverished farm laborers under the thumb of their former masters. Legal freedom had done little to address economic (and hence social) concerns. Similar to Russian serfs after the 1861 revolution, not much actually distinguished their daily lives as free men from slavery. One of the most famous of all ex-slaves, Booker T. Washington, conceived of an institute in which African American men recovering from the traumas of slavery might leave their homes and farms and develop the artisan skills many had learned during bondage.[i] The Hampton and Tuskegee Institutes in Alabama and Virginia respectively were technical institutes with a difference: through craft and cooperation, Washington hoped a new, free black identity might be forged, one capable of teaching a new generation of black men and woman born after the formal end of slavery but not yet into a world of sustained economic hope. Washington was both a pragmatist and an idealist. He recognized that people are bruised by their chains; from his own slave past, he knew that his master’s humiliations could be internalized as fear, making him suspicious of others, even his own. Yet he made changes that are as astonishing to us now as to someone living in the early nineteenth century. Gender equality was inscribed into the institutes, as well as racial recovery. Crucially, he recognized the workshop as the most important physical space for rehabilitation and ambition.

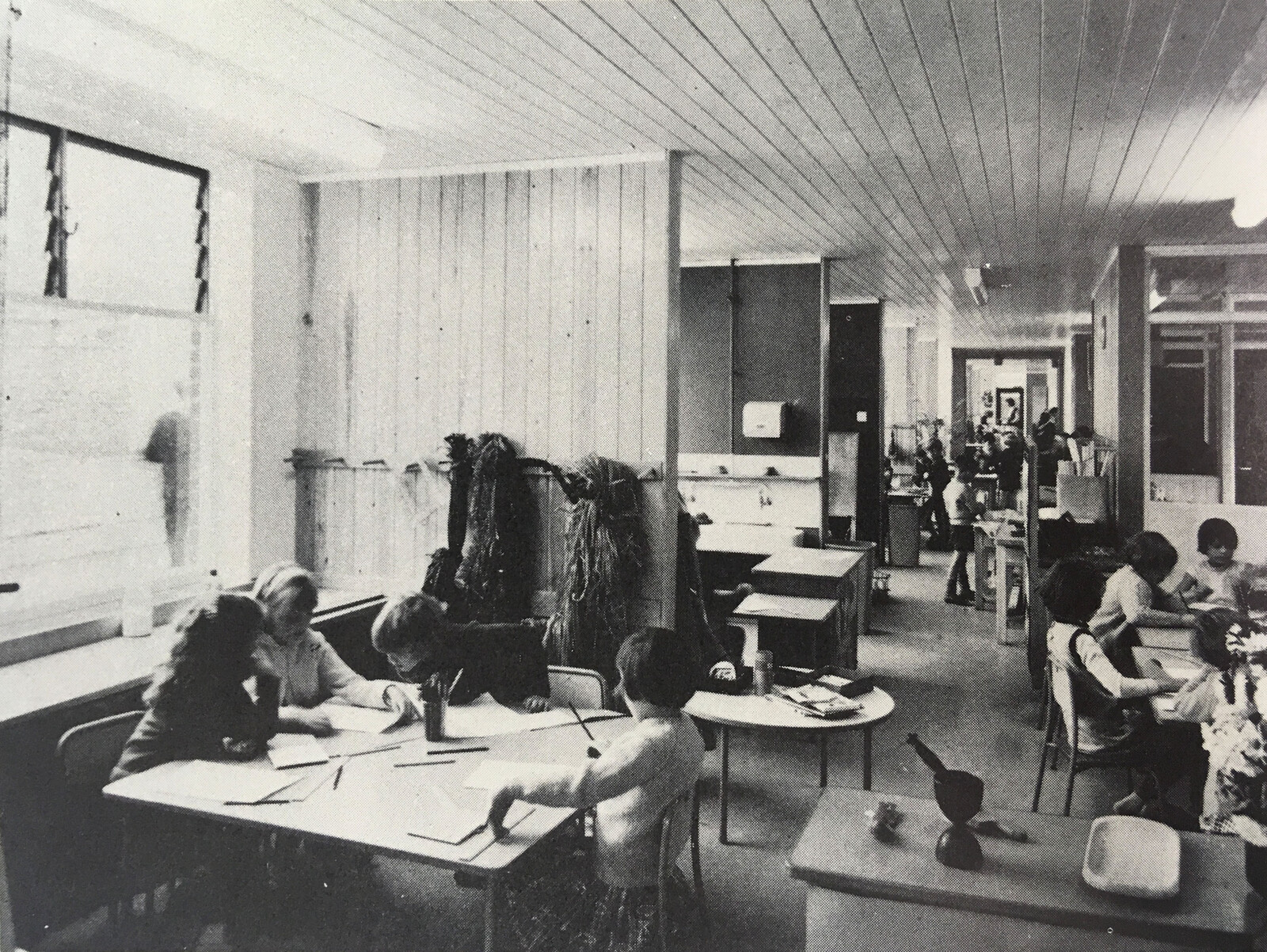

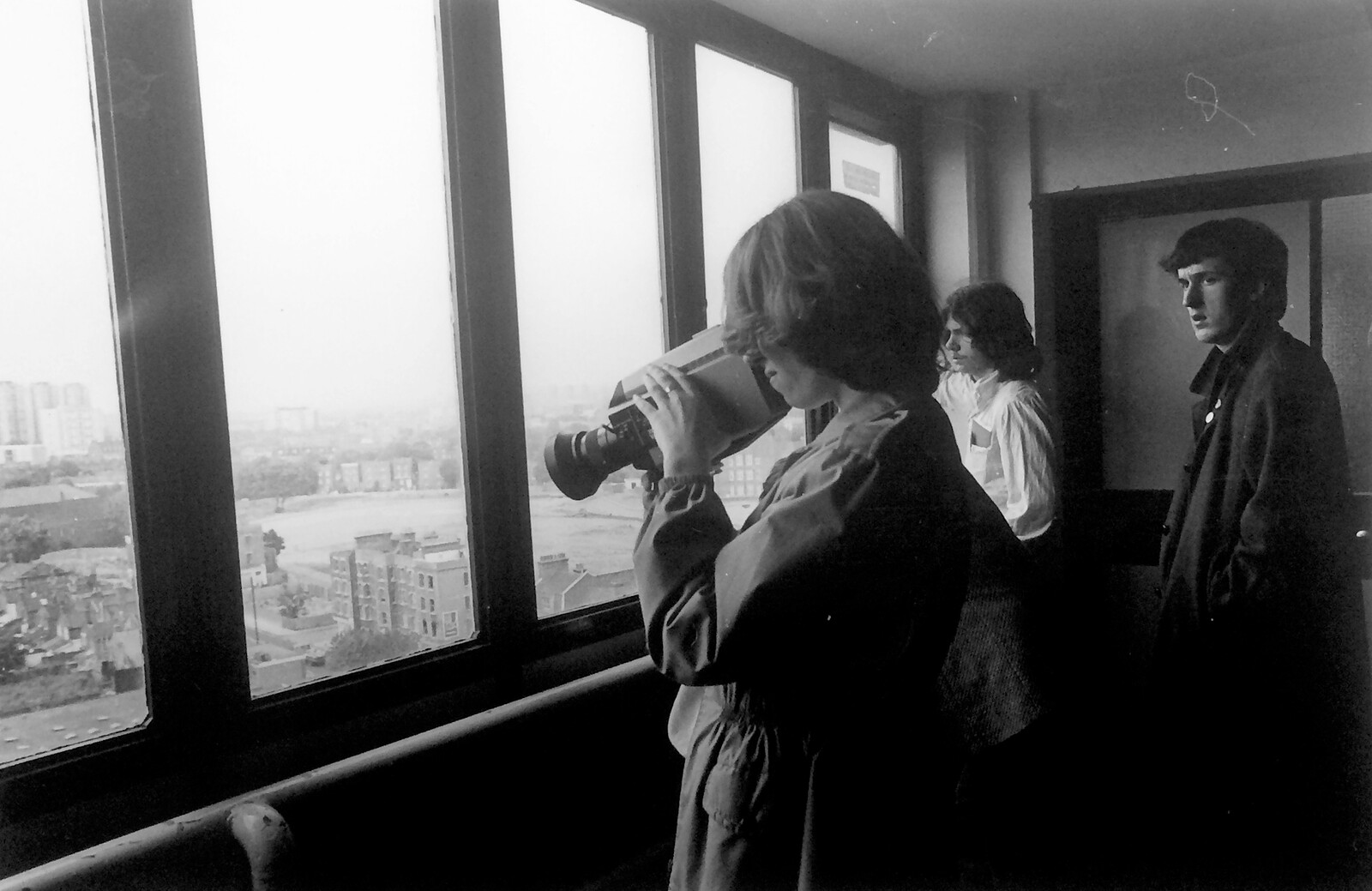

Owing to the school’s sudden and rapid increase in students starting in 2014—with the school doubling, tripling, and quadrupling in size over three subsequent years—the GSA lacked studio space, offices, or a workshop. A spider’s web of spaces around the city thus became the school’s de facto maker and review spaces. From a partnership with a community-based shared workshop enterprise The Coloured Cube to an abandoned laundromat, car repair, countless bedrooms, and garages, students found ever more ingenious ways to make, build, test, and craft projects that sought to transcend the limitations of their largely Eurocentric undergraduate education.4 They branched into storytelling and performance as legitimate modi operandi for a new, transformed, and decolonized curriculum-in-the-making. A History & Theory Colloquium was held in the streets; a global acoustic and building materials company manufactured moveable walls; young, recent graduates took on the role of designing and project managing new office spaces. Students’ work moved into projection, film, installation, and story-telling instead of the traditional essays, theses, and leather-bound portfolios that typically describe an architecture student’s output.

This quality of “make do,” or innovative adaptation, is often described as “African,” or particular to developing countries, where infrastructure and systems are not as fixed or reliable as they are in the West (and, one supposes, increasingly the ‘East’). There’s a truth to that: in places where the supply of electricity and water is patchy, a streak of pragmatic individualism often prevails. Where the municipality or the state is found wanting, individuals or private entities step in, often more inventively and creatively than those tasked with the responsibilities in the first place.

The Space and Time of Instruction

In contrast to the GSA, at Spitzer, the physical infrastructure is robust, up-to-date, and generous. Studio spaces are light-filled; there’s a well-staffed and stocked model workshop and a partially-complete Fabrication Lab with the latest robotics and fabrication tools. Here, the challenges for anyone wishing to implement radical change are different, slippery. Resistance is hidden primarily in the non-physical infrastructure, buried beneath innocuous-sounding words like “curriculum,” “core classes,” “electives,” and most pernicious of all, the “timetable.” It’s hidden in the terminology, but it’s also hidden in the spaces which correspond to that terminology. “Studio” teaching (which takes place in the spaces designated as “studios”) is prescribed on certain days; seminars (held in “seminar spaces or classrooms”) on others. Making is done in maker-spaces; IT instruction in the IT Lab.

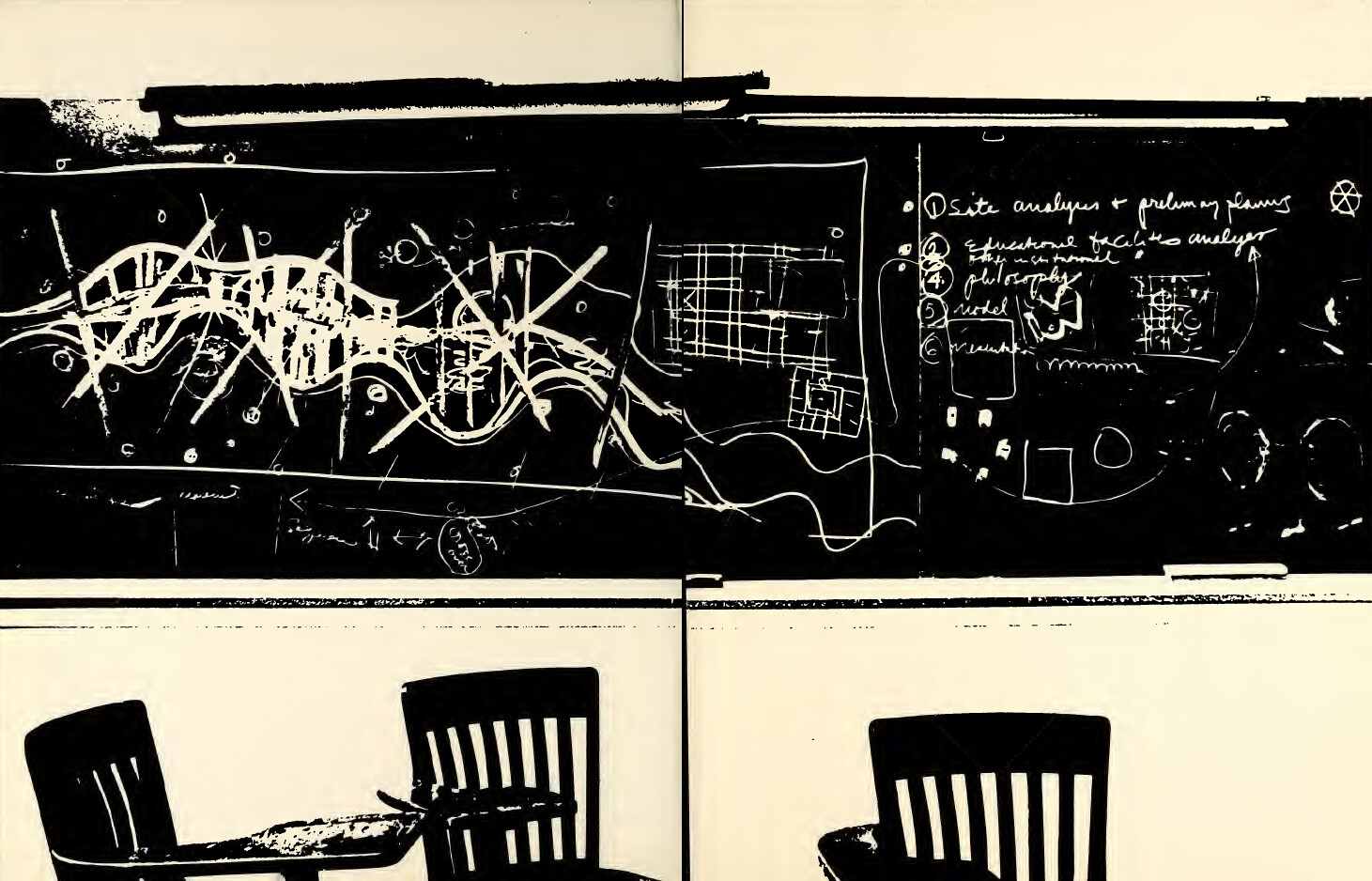

Class schedules dictate more than the stated number of hours spent with a subject or in a lecture hall. The timetable choreographs the progression, combination, and direction of learning. The academic day is carefully parceled into fifty- or ninety-minute slots. Lunch breaks are mandatory. The apparent inflexibility of the spreadsheet dictating timetabling permutations actively and aggressively inhibits cross- or inter-disciplinary learning. Students enrolled on any given program will find it next to impossible to synthesize their learning in anything other than a superficial way, which is counter-intuitive given that architects, in particular, are supposedly trained to synthesize—not fragment—knowledge.

One after the other, options and initiatives very quickly run up against institutional bureaucracy (of which the timetable is only one small part). By the time change, announced so vigorously and optimistically at the beginning of the year, actually hits the ground, it is often not possible to distinguish it from what went before. Plus ça change. As Einstein (is said to have) said, “the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, expecting a different result.” There is a tension between the conceptual aspects of these brave attempts at change and the structural realities of educational systems that, despite protestations to the contrary, are largely engineered to resist change.

To return to South Africa, it’s important to understand that the protests of 2015 and 2016 were not simply—or only—political in nature. They included, albeit indirectly, questions of space and form. Although these were not addressed specifically to architects, architecture was (as it usually is) complicit. Aside from the fact that the protests physically took place on campuses and in city streets across the country, the physical objects under attack—statues, porticoes, boardrooms, lecture halls—were both symbolic and real. Architecture was no innocent bystander; architecture was both perpetrator and aggressor, contemporaneously and historically. As philosopher and political theorist Achille Mbembe says so eloquently:

When we say access, we are also talking about the creation of those conditions that will allow black staff and students to say of the university: “This is my home. I am not an outsider here. I do not have to beg or to apologize to be here. I belong here.” Such a right to belong, such a rightful sense of ownership has nothing to do with charity or hospitality. It has nothing to do with the liberal notion of “tolerance.” It has nothing to do with me having to assimilate into a culture that is not mine as a precondition of my participating in the public life of the institution. It has all to do with ownership of a space that is a public, common good. It has to do with an expansive sense of citizenship itself indispensable for the project of democracy, which itself means nothing without a deep commitment to some idea of public-ness.5

The South African “project of democracy” clearly implies a physical as well as political space, and one in which the question of access is paramount. What will be the physical form of the new decolonized university? What will it look like and where will it be located? What do we mean by “access” and, even more importantly, what do we mean by “belong”?

Unit Systems

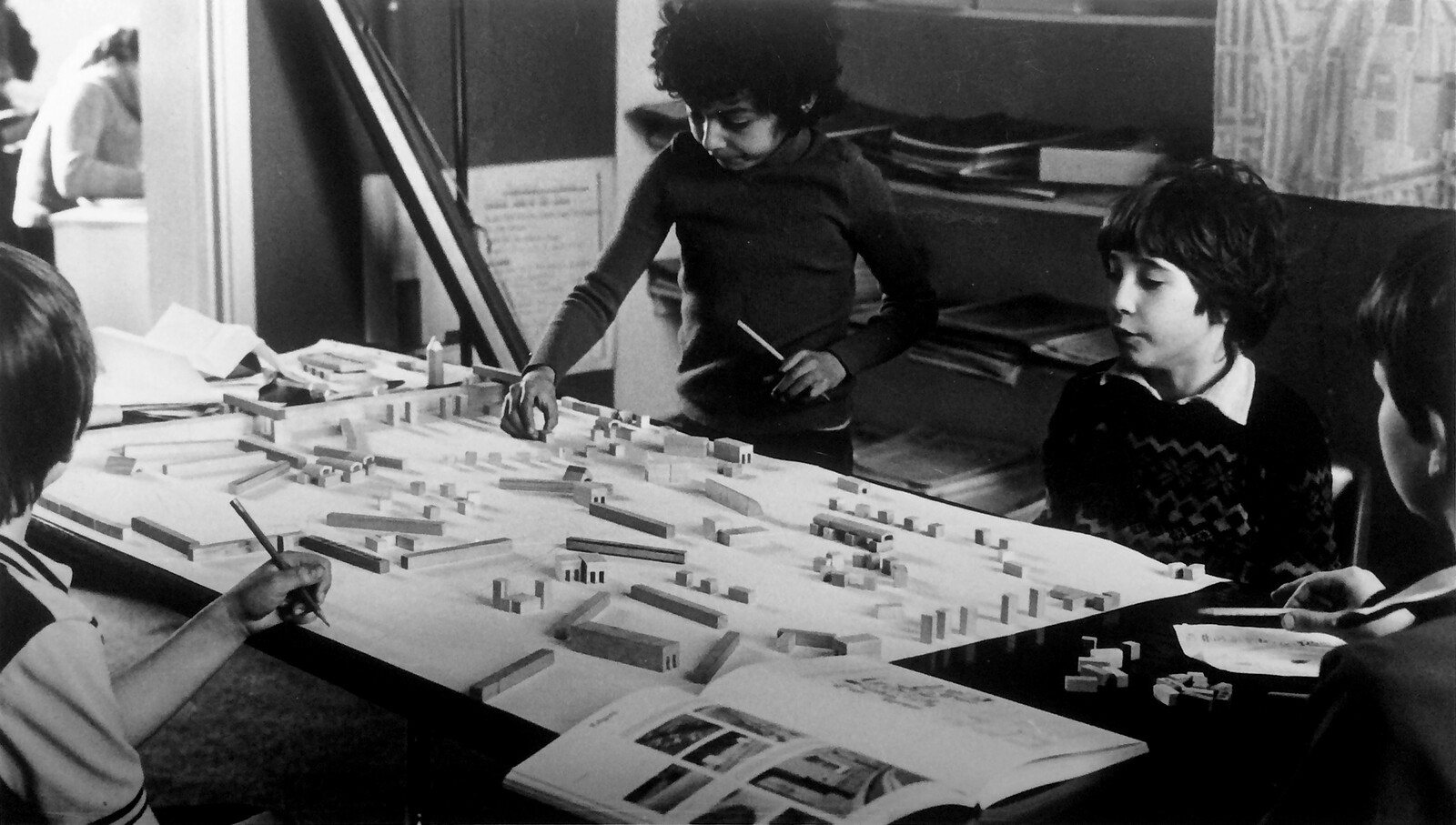

On February 2, 2015, a pedagogical experiment began at the GSA to replace the traditional semester- and module-based curriculum. Unit System Africa looked to Alvin Boyarsky’s radical pedagogical model, begun in London at the Architectural Association (AA) in 1971, for its template. At that time, according to Irene Sunwoo, the most well-known chronicler of Boyarsky’s educational experiment:

After the merger’s eventual dissolution and in hopes of recovering institutional stability, students and staff elected the Canadian-born architectural educator Alvin Boyarsky (1928–1990) as chairman of the AA—an arrival that marked the beginning of a new episode in the school’s history of independence. Accordingly, as an analog to Introduction Week’s scheduled tours of London, students also received a guided tour of the AA’s academic terrain, recently refurbished by its new chairman. Throughout the lecture hall, studios, and other rooms within the AA’s Bloomsbury residence, a series of Georgian townhouses located at 36 Bedford Square, tutors and staff outlined the responsibilities of academic departments and facilities, explained individual teaching objectives, and lectured on their current architectural preoccupations. Even the welcome lunch for Introduction Week—boasting an international assortment of Indian, Greek, Italian and English menus—was “served in different parts of the school.” Indeed, the occupation of the school premises by this programmatic ‘‘menu’’ heralded the institutionalization of Boyarsky’s ‘‘well-laid table,’’ his metaphor for an educational model that confronted the student with a rich selection of divergent theoretical positions and design methodologies. At the AA, Boyarsky’s ‘‘well-laid table’’ indelibly recast the institutional identity of the school, which began to operate as a testing ground for alternative forms of architectural production. Whether exploring ecology or conceptual art, politics or phenomenology, pedagogy both transgressed the limits of professional practice and proclaimed a critical distance from architectural modernism.6

The AA model was transplanted with almost no modifications, directly into the African context. In 2015, in its first year, there were three Units with a total of fifty-two students; in 2019, when I left, there were six Units with a total of ninety-three students. Undoubtedly, the school’s biggest challenge to date has been the lack of available teaching staff with enough experience of, and commitment to, the ideology of a transformative pedagogy. Staffed almost exclusively by adjunct instructors (part-time tutors), many of whom have only just graduated, it has been fascinating to watch this generation of young African architects-in-waiting “see” their own context in ways that the previous two generations cannot. Part of the school’s success stems from the fact that the instructors (tutors) are themselves deeply engaged in the exploration of what it means to transform a curriculum, a discipline, a practice. Through deft mélanges and mixtures of media—film, written word, fiction, oral storytelling, and performance—they lead students towards new ways to describe, craft, and explore space, material, and structure(s), all of which point to their capacity to imagine what is not yet here.

In the student work that results, whether through performance, installations, material investigations, or digital technologies, there are glimpses of combinations of space, material, and form that are difficult to capture, let alone represent, but nonetheless possess a powerful experiential presence. Jiaxin Gong, a third-generation Chinese–South African student, re-imagines the archive as a place of fleeting and kinetic architecture that mimics the daily experience of Johannesburg’s undocumented migrants, always a step ahead of the law, unable to settle. Gugulethu Mthembu’s work draws on poetry, performance, and installation to address issues of gender and African patriarchy. Her projects cannot be drawn in a conventional sense but possess a schizophrenic spatiality which jumps between the spoken word and video; between artefact and installation, perfectly encapsulating the multiple worlds which she, a Millennial black South African woman, must necessarily occupy. Her work is influenced by sources as diverse as German artist Rebecca Horn and American theorist Jennifer Bloomer, yet remains authentically “African” in the way it constantly negotiates and translates material and references from other, disparate sources. Hers is—so far—an architecture of translation, dispossession, and repossession, qualities that she embodies in her everyday existence.

Where these young Africans construct spaces that are fluid, ephemeral, weightless, and even site-less, their day-to-day realities could not be more different. For some, living in an urban conglomeration of over six million inhabitants without an integrated public transport system, getting to and from university is an everyday challenge. During recent xenophobic attacks in downtown Johannesburg, students from neighboring African countries who use the informal shared taxi network to travel around the city stayed at home. Fearful that their accents and inability to speak Zulu or Xhosa would mark them as targets, their relationship to the city became, at best, precarious.

This overriding sense of precarity underrides their work and often translates into delicacy, even fragility, with many choosing to work mostly—or even entirely—in the digital realm. For a continent whose leaders and economists often lay claim to “leap-frogging” fixed-line technology and infrastructure, this is a statement that is simultaneously full of possibilities and dangers.[1] Pliny the Elder is purported to have said, “ex Africa semper aliquid novi” (there is always something new out of Africa), seeking an explanation for the supposed proliferation of strange, hybrid animal species in Africa, citing the leopardus—a maneless male lion which was believed to be a cross between a leopard and a lion—as an example. Yet when used on its own, the phrase is shorthand for the continent’s imagined capacity for producing uniqueness, bringing forth novelties, things of mystery and wonder, equal parts admiration and despair.

In the Fourth Industrial Revolution, things are moving faster than ever. Political dissent, wars, and economic crashes are affected and adopted through the same planetary crunching of time and space, across media and image, as is Beyoncé’s new hairdo. This is the age of wildfire.

—Sarah de Villiers

Unit System Spitzer is in its earliest days of planning, no more than (as I write) an idea. COVID-19 has, undoubtedly, derailed many things, not least the usual “let’s meet and sit and talk this through.” In place of those meetings, virtual tele-conferencing will step in, where the advantageous nuances of tone, body language, persuasion, and debate will be flattened, if not made obsolete. South Africa’s political volatility over the past five years unwittingly created a space in which possibilities to experiment and explore could flourish. The US, in an election year, in the midst of markets and healthcare systems crashing, is a different beast.

Ideas spread like lightning; new trends appear and disappear; ambition and aspiration coalesce. As the world around us changes, so too does the nature and purpose of education. Strange, but also amazing to think that an idea begun in London in the 1970s and transplanted in South Africa in the teens might now be the precursor for a different kind of school sitting on the border between Harlem and Manhattan, embodying all the tensions and opportunities that migration and translation implies.

Lewis Carrol, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (London: Macmillan, 1865).

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Act was signed into law by President Obama in 2012.

Mario Carpo,”We Can’t Go on Teaching the Same History of Architecture as Before,” Metropolis, November 5, 2018, ➝.

See ➝.

Achille Mbembe, “Decolonising Knowledge and the Question of the Archive,” public lecture given at Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 2017, ➝.

Irene Sunwoo, “From the ‘Well-Laid Table” to ‘The Marketplace’: The Architectural Association Unit System,” Journal of Architectural Education 65, no. 12, 2012.

Architectures of Education is a collaboration between Nottingham Contemporary, Kingston University, and e-flux Architecture, and a cross-publication with The Contemporary Journal.