The late 1960s saw the birth of two radical ideas in the fields of education and environment. In education, the deschooling movement began with a seminar in Mexico entitled “Alternatives in Education.” For the scholars involved, schooling was an institution that perpetrated an unjust social order through a “hidden curriculum” and which had to be changed in order to achieve social justice.1 As a result of their meetings, two years later, Ivan Illich published Deschooling Society, where he advocated the abolition of schools and their replacement with “a new style of educational relationship between man and his environment.”2

For Illich, the physical environment was a freely available resource where people could learn on their own terms.3 He loosely proposed an alternative system of entangled educational networks outside the remit of the school, combining educational objects, peer learning, mentorship, and reference services. His idea was to create a framework “which constantly educates to action, participation, and self-help.”4 The proposals of the “deschoolers”—including Illich, Paul Goodman, and Everett Reimer—were considered utopian and unscholarly at the time, but they became popular among progressive educators and the New Left, fueling a stream of libertarian educational practices worldwide.5

Meanwhile, ecological disasters and the indiscriminate use of natural resources in the US inspired Wisconsin senator Gaylord Nelson in 1969 to organize an environmental “teach-in.” His aim was to encourage people, and especially youth, to become aware and involved in protecting the environment. Instead of taking a top-down approach, Nelson proposed that anyone could organize a meeting to teach others what they knew about the environment.6 A year later, in April 1970, Earth Day triggered a nationwide grassroots movement of peer-to-peer learning that brought millions to the streets, including 10,000 schools and 2,000 colleges and universities. An initiative that started as a local environmental education project created the first North American green generation and propagated the environmental movement.7

The ripples of these two radical ideas reached Britain and materialized in the work of anarchist writer Colin Ward. With a background in architecture, education, and anarchist publishing, Ward combined the ideas of the environmental movement and the deschoolers, initiating a network of people, places, and pedagogies that used the environment as a tool for learning.8 However, rather than concentrating on the natural environment, as most projects did at the time, Ward advocated for the study of urban areas as a path to active citizenship.

One of the initiatives under Ward’s leadership, the Urban Studies Centres (USCs), triggered a grid of more than thirty self-organized urban learning centers across the UK to promote awareness of the built environment. Even though the USC’s main aim was to widen participation in the construction of cities and help people become “masters of their environment,” they also, as a side-effect, proposed a way to “deschool architecture” by making architectural and urban education publicly available.9

1.

After years of shortages and difficulties caused by the Second World War, the 1960s in Britain was a decade characterized by economic prosperity and affluence thanks to postwar recovery and full employment. Cities like Liverpool and London experienced a cultural boom of youth and creativity. Services flourished, legislation was liberalized, and culture was democratized through educational reforms and new media.10 However, changes to Britain’s global position in the economic market and the decline of its empire were two problems simmering underneath the surface that would unleash a crisis in the following decade.

Britain struggled to compete with the strengthened postwar economies such as the USA, Germany, France, Italy, and the Netherlands, due to “her overmanned, undercapitalized and obsolete” industries.11 This, combined with the global oil crisis, pushed the UK into recession and made the 1970s the “most tortuous peacetime years in the modern era.”12 Major industrial cities like Manchester and Newcastle were struck by the recession the hardest.13 Unemployment and inflation quickly rose while growth remained slow. Furthermore, wartime damage resulted in decades of housing shortages.14

Postwar planning doctrines promoted large-scale redevelopment, inner-city urban renewal, and widespread “slum clearance” programs to provide space for high-rise public housing and motorways.15 More than five million people were relocated and established social networks broken up, even when “houses were structurally sound and there was strong local resistance.”16 As a result from these policies, throughout the 1960s planning proposals were increasingly confronted by public rejection, with residents organizing into action groups and associations.17

2.

While protests made clear that citizens were engaged with their local built environment, the government did not know how to transfer this interest into the planning or design process. In 1965, the Ministry of Housing and Local Government set up a Planning Advisory Group to tackle urban unrest concerning new projects, which reported that the root of the problem was “inadequate participation by the individual citizen.”18 As a result, in 1968, the government commissioned Arthur Skeffington to lead a research project to find ways of securing public participation. A year later, the government published the Skeffington Report, which offered local authorities ways to engage with the public.19

Following the report’s publication, community consultation became a required step in the planning process. As geographer and planner Dennis Hardy explained, planning committees were not able to openly dismiss people’s opposition to development plans anymore.20 However, Joan Kean, also a planner and a participant of the urban studies movement, argued that tokenism and failed participation exercises led many to quickly believe that participation was not enough, and that education was a necessary prerequisite.21 Community forums and education in architecture and town planning were then championed as a way of making children and communities conscious of their civic rights and duties, as well as preparing them for participation.22

While the Skeffington Report promoted participation and the study of the urban environment, the Russell Report a few years later promoted adult education “firmly rooted in the active life of local communities.”23 These governmental reports paved the way for two types of educational initiatives than combined public built environment education and local life-long learning. Firstly, several local authority planning departments hired professionals to mediate planning proposals to teachers, children, and communities. Secondly, it pushed organizations related to the built environment to develop their in-house public educational schemes for all ages. One of the most influential organizations in this respect was the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA).

The TCPA is a London-based planning organization originally founded by Ebenezer Howard that has influenced British town planning since the beginning of the 20th century.24 Until the beginning of the 1960s, its strategy was to address and incorporate influential people rather than connecting to the public,25 but after the publication of the Skeffington Report, the TCPA “pioneered community participation and education on planning and the environment.”26 During the 1970s, the TCPA led the debate through innovative initiatives like planning aid, community technical aid centers, the Bulletin of Environmental Education, town trails, and Urban Studies Centres. Part of this institutional capacity was possible thanks to the advocacy of its first educational officer, Colin Ward.

Cover Bulletin of Environmental Education 71, March 1977. Source: Town and Country Planning Association Archives.

Cover Bulletin of Environmental Education 22, February 1973. Source: Town and Country Planning Association Archives.

Cover Bulletin of Environmental Education 61, May 1976. Source: Town and Country Planning Association Archives.

Cover Bulletin of Environmental Education 109, May 1980. Source: Town and Country Planning Association Archives.

Cover Bulletin of Environmental Education 71, March 1977. Source: Town and Country Planning Association Archives.

3.

As explained by education professors Catherine Burke and Ken Jones, Colin Ward was concerned about the “relationships between human beings and the world they have made.”27 For Ward, engagement with the built environment was important not only for its aesthetic dimension but also because it encoded power relations in a visible form.28 Ward combined education and built environment know-how through practice at the TCPA’s education unit.29 The team would later be completed by Anthony Fyson, who had worked in a planning department and trained as a geographer and teacher before joining, and Eileen Adams, an art teacher and researcher who developed a pioneering program in collaboration with council architects.30

According to the TCPA’s director, David Hall, the functions of the association in 1973 were both as a pressure group and an educational body.31 It established the education unit with the intention of disseminating urban education methods through three interrelated initiatives: firstly, a publication called the Bulletin of Environmental Education (BEE), where people could share ideas and best practices; secondly, urban trails to make accessible a place-based educational tool; and, thirdly, the Urban Studies Centres as a space were urban learning would take place.32

The BEE was the structural spine of the urban studies movement, running monthly for twenty years and edited in its first decade by Ward and Fyson.33 For Brian Goodey, the magazine was vital to make available theory and methods for environmental education nationally and abroad.34 According to Roger Hart, BEE inspired many teachers at the time, including himself.35

One of the main achievements of BEE, as explained by Burke, was to depict “the school as a potential site for extraordinary radical change in relations between pupils and teachers and schools and their localities.”36 The magazine also worked as a vehicle for other educational experiments that could be replicated and scaled across the country.37 One of the methods most widely implemented was the urban or town trail; a directed walk in an urban area that pointed out relevant built features with a clear educational purpose, using a map with pictures, data, and statistics.38 While there were plenty of nature trails by the 1960s, BEE and the TCPA played an essential role in disseminating a methodology for teachers and students to easily design urban trails in cities and towns.

Map of 31 Urban Study Centres across the UK in 1980. Drawing: Sol Perez-Martinez.

4.

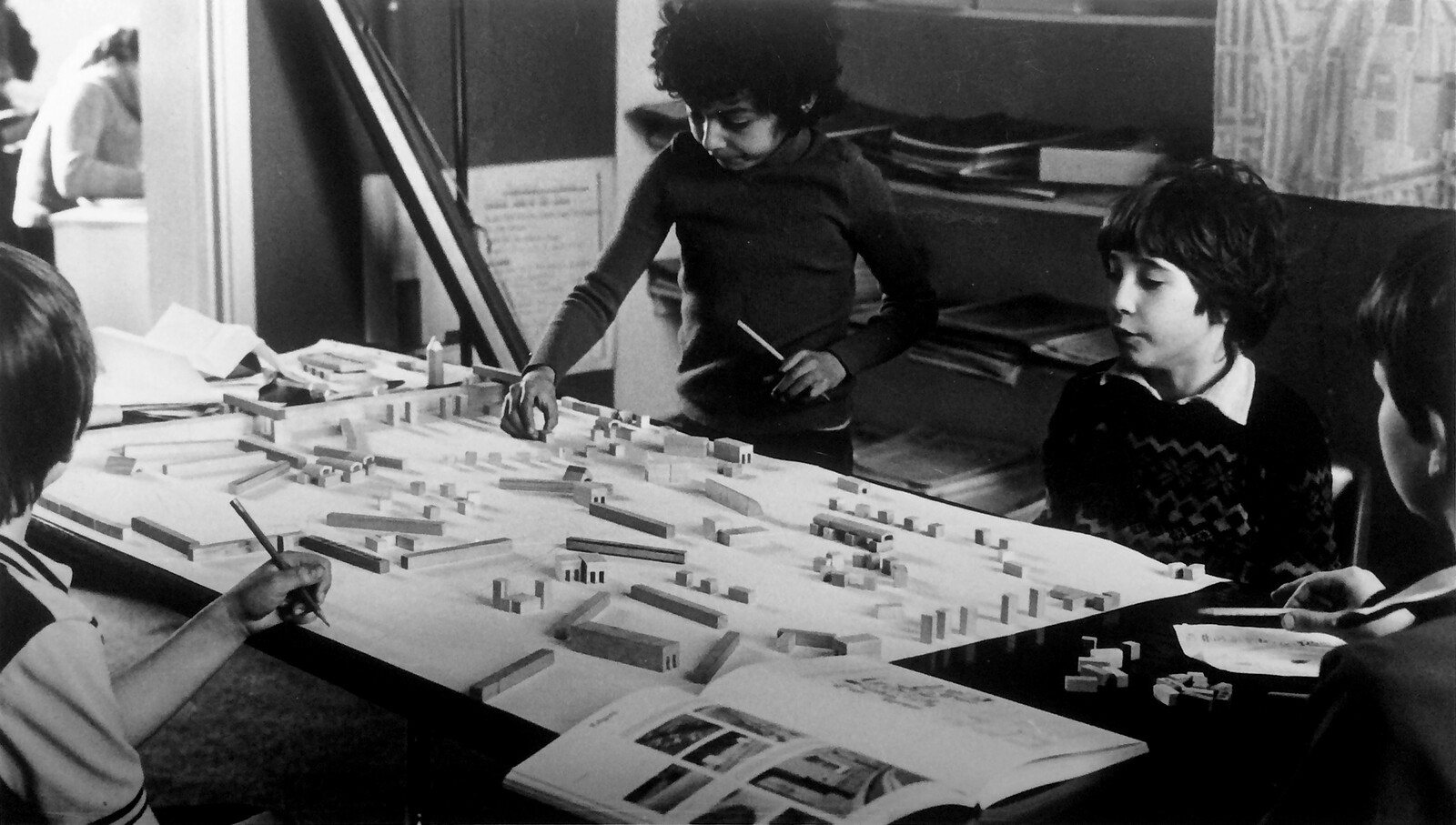

The urban trails and the learning methods of BEE mostly took place outdoors and in community spaces outside the school, ideally in an Urban Studies Centres (USC). USCs were independent organizations based on the idea that only people with environmental literacy would be able to participate meaningfully and have agency in the construction of their surroundings. Advocated by the TCPA and created by self-organized interdisciplinary groups, USCs were spaces that promoted learning from the built environment and, like the deschoolers, encouraged education for participation, action and self-help.39

Centers had the double function of integrating citizens in the building process, while at the same time making professionals aware of the relevance of hearing people’s needs. According to Fyson, the USCs “would provide the neutral ground through which local government information about the environment and planning could flow to both the schools and the adult population, giving space to channel public opinion back to the planners.”40 As such, the creation of the USCs was a direct response to the government’s concern to include people in planning,41 allowing as well to crystalize an institutional interest at the TCPA to democratize city making.

Advocated by Ward and Fyson through lectures around the country and in BEE, USCs lacked a defined framework and an overarching institution, which meant they varied in structure, scale, activities, and funding.42 However, they shared two aims that allowed communities and especially young people to become aware and take action over their local built environment: firstly, to provide resources for critical inquiry, and secondly, to offer a meeting space to discuss environmental issues.43

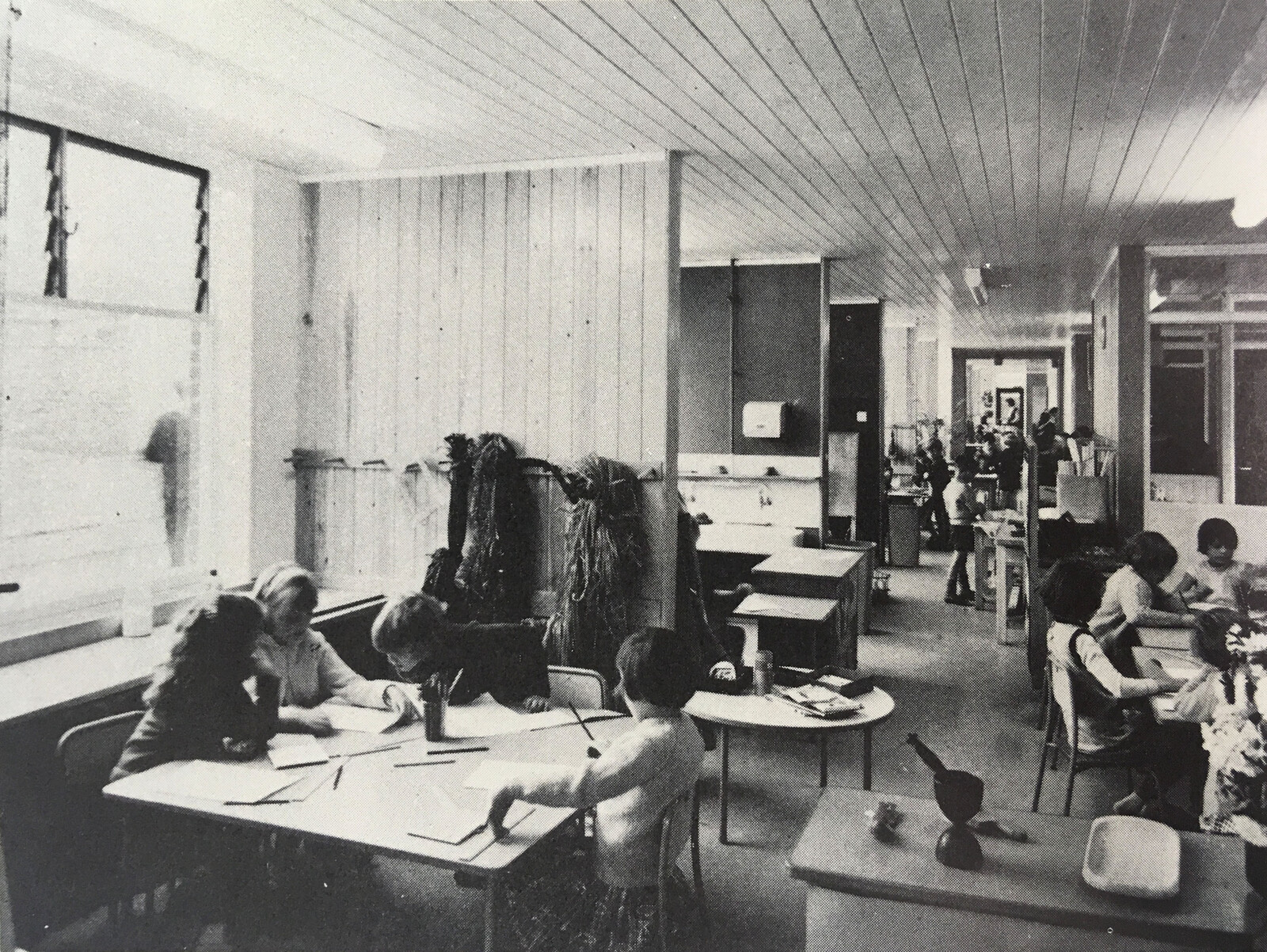

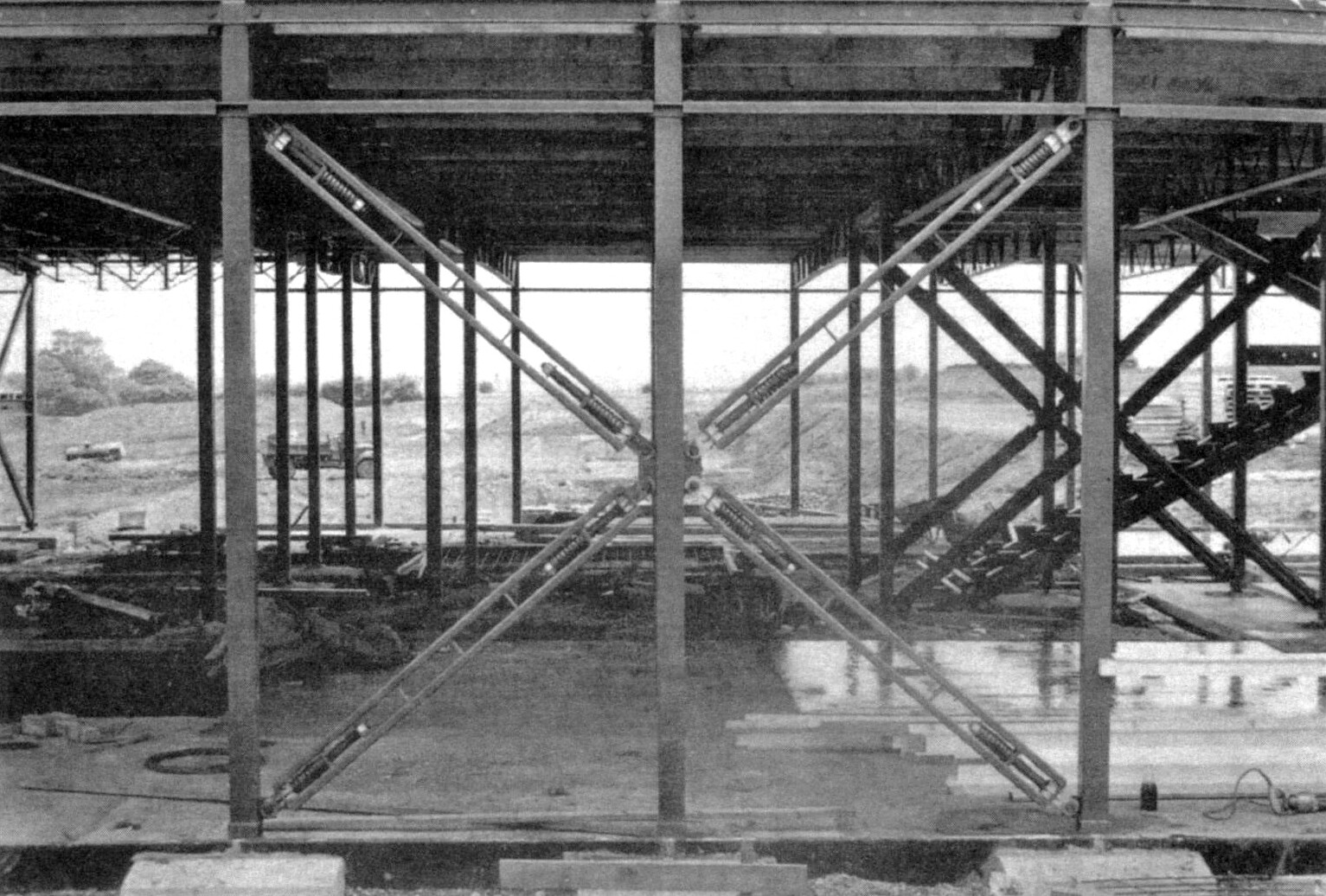

Based on an interdisciplinary collaboration between environmental professionals and teachers, pedagogical activities used the local urban environment as a primary resource. Through the USCs, Ward advocated for issue-based learning and place-based methods, which gave an active role to the learner and considered learning as a situated practice. To set up a center, the TCPA encouraged the use of derelict buildings in city centers.44 In 1973, an article in BEE proposed the following functions for USCs:

a learning base for visiting local schools, which in some cases, included residential accommodation

a teaching resource center where teachers from different schools and subjects, who were interested in environmental education could gather

a visitor center, following the lines of the architectural interpretation centers championed by Ewan McEwan and implemented around the same time

a connector between planners/architects and the public, as a space for planning consultation

a venue for community forums following the Skeffington Report

an archive of urban resources

a catalyst for meaningful urban change

as an alternative institution to the school.45

The education unit refrained to “prescribe a single blueprint for center development” since they envisaged that the needs of these multi-purpose centers would “vary from place to place.”46 They encouraged using existing places like libraries, museums, churches, schools, or teachers centers that could be extended or combined with the USCs, reinforcing that “purpose-built centers are not needed.”47 Similar to community schools and following deschooling ideas, the Centres would break down “the firm distinction between education and leisure,” transforming the whole physical environment into a learning opportunity.48

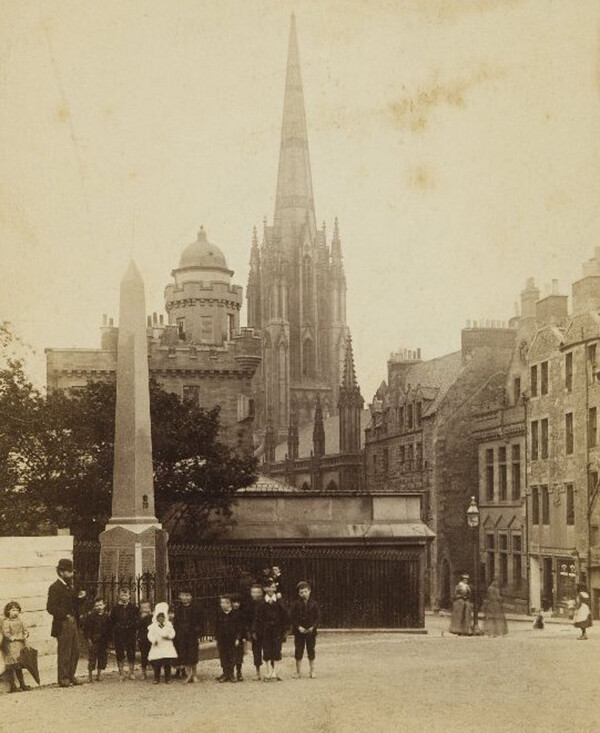

Patrick Geddes directing an urban trail next to Outlook Tower. Source: Centre for Research Collections, University of Edinburgh, CRC Gallimaufry, Coll-1167/PSE/X/1, Catalogue No.A2.139.

5.

In an article in BEE, Ward acknowledged that the Scottish thinker Patrick Geddes had developed a prototype of the USC eight decades earlier.49 With a display curated by Geddes in 1892, Edinburgh’s Outlook Tower aimed to connect citizens with their surroundings.50 The building was organized as a “civic observatory” where people could see their local environment from a new point of view.51 The tower delivered a more effective and affective kind of learning, which encouraged citizens to be active and involved in the construction of their environment. Geddes insisted on the relation between “young humans” and the environment because he believed that an understanding of and sympathy with the environment would lead to awareness, value, and its potential improvement.52

The origins of Urban Studies Centres lie in Field Studies Centres; a set of buildings scattered around rural Britain since the 1940s that allowed children to explore the outdoors and learn about the natural environment. By 1973, the number of Field Study Centres was growing rapidly thanks to the teacher’s demand for fieldwork as an effective pedagogical method. Some sites were overused and there was a clear need to create more facilities.53 Picking up on the observation that that “schools are exploding into the environment,”54 Ward and Fyson advocated for the creation of an urban alternative.55 Their main activity would be “streetwork”: fieldwork in an urban setting, as the inquiry of the cities and towns where most children lived and learned.56

The TCPA education unit established the Council for Urban Studies Centres (CUSC) to support the Centres’ initiatives through advocacy and connect to academics, politicians, and professionals in the creation of centers around the country.57 Among CUSC’s thirty-two members were MPs, professors, advisors, and trustees. The last report of the CUSC in 1984 presented thirty-seven centers that approached built environment education with different strategies.58 Even though their evolution was extensively covered in BEE until 1988, there are almost no publications about Urban Studies Centres after that date, apart from brief mentions in texts by Roger Hart,59 people involved in BEE,60 and scholars studying the work of Ward, yet none of whom delve into their methods or history.61

6.

Among the Urban Studies Centres developed throughout Britain, one stood out in terms of its impact in the local community, and was used by Ward as an exemplary enterprise of community development in his seminal book The Child and the City.62 Founded in 1974 in an area of west London confronted with the effects of decades of top-down planning, the Notting Dale Urban Studies Centre was the first of its kind. Its director, Chris Webb, described Notting Dale as a difficult part of London, affected by “improvement” plans, divided by concrete sky-high motorways, peppered with high-rise towers, and dealing with rampant inequalities among neighbors.63

John Reese was aware of the difficulties of the community living in this area. As an economics teacher at Harrow School—a private boarding school on the outskirts of London—Reese was involved in the Harrow Youth Club that the school had run as part of its missionary work at Notting Dale since 1883.64 After he heard Colin Ward advocating for the creation of an Urban Studies Centre as a way of improving the relationship between people and the urban environment, he argued that Notting Dale would be the right context in which to try out this model. Shortly after, Harrow School supported the initiative, transforming the old vicarage next to the Harrow Club into “Britain’s first fully fledged Urban Study Centre.”65

Notting Dale had the double aim of serving local needs while welcoming visitors and enabling Harrow students to visit an inner-city area. The Centre had residential capacity in order to support an in-depth study of the area, allowing groups of students and their teachers to spend the night and become embedded in the concerns and opportunities available. According to Webb, the Centre had “a pedagogic, social and indeed political purpose” in the local area, using urban studies as a “powerful form of political education.”66

The learning experience at Notting Dale was “autonomous, collaborative, and self-generating,” with “no right or wrong answer, but a range of beliefs and opinions.”67 The Centre described its ethos as “a fluid and flexible learning context, within which students and adults generate much of the information and opinion on their area themselves.”68 It was created as an enabling place, where people could experience the possibilities of participation.

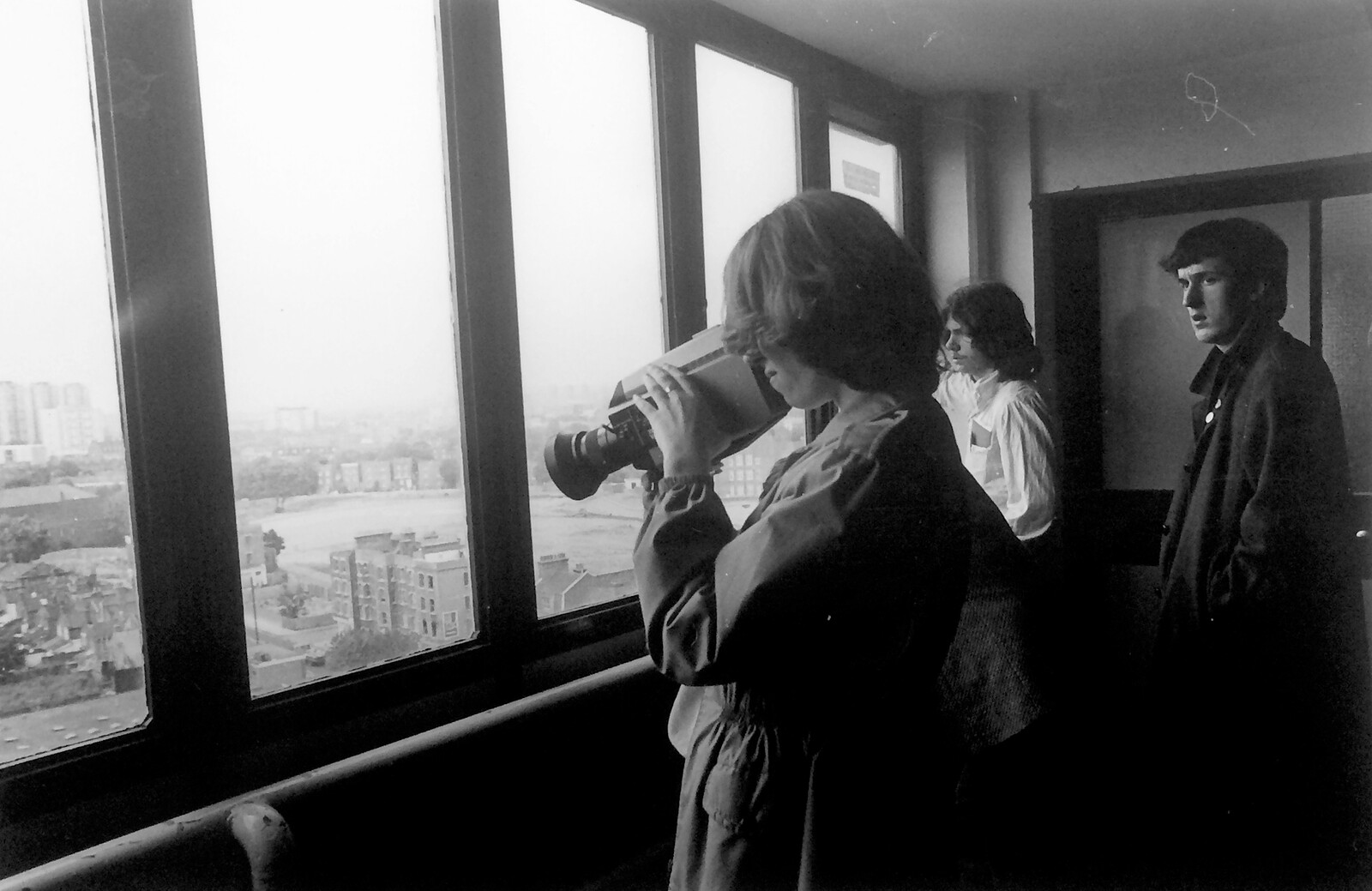

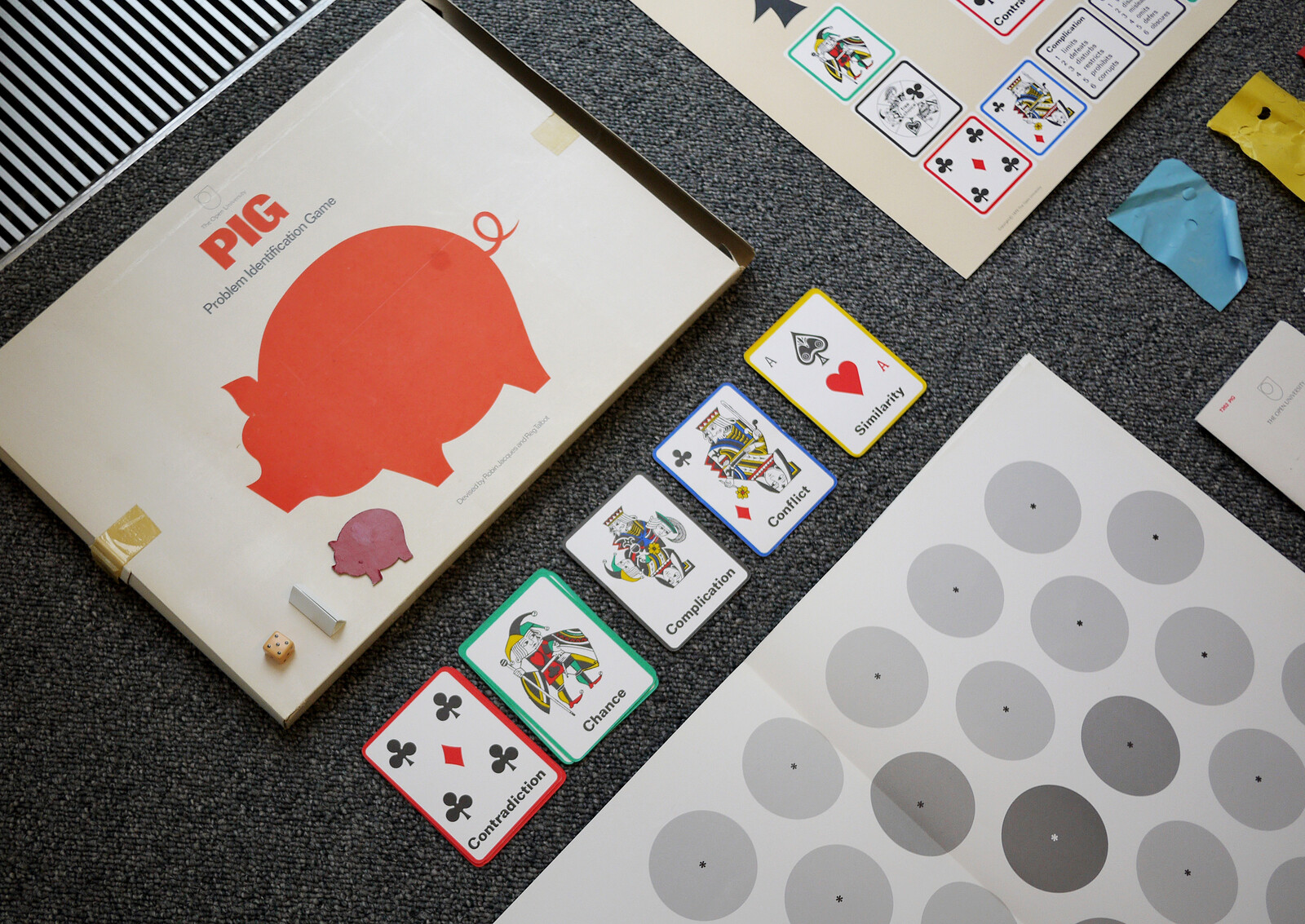

In order to engage his students, Webb used active learning, learning by doing, and collaborative problem-solving.69 The Centre included three large working rooms, two large dormitories for sixteen students, and accommodation for their teachers. There was a dark room and a wet room to process photographs, a media room with state-of-the-art printing machines, a large communal kitchen, and administration facilities.70 The equipment—which was available to anyone who visited the Centre—included recorders, cameras, projectors, developing and printing equipment, typewriters, and other tools not ordinarily accessible for schools or local groups.71 Three people were employed full time—the director, a teacher/researcher, and a secretary—but Webb described the work environment as horizontal, with everyone doing everything.

A typical day at Notting Dale would include an urban trail prepared by the USC’s team in which visitors recorded their points of interest, followed by a group discussion about the issues present in the neighborhood. After lunch, students would use design thinking and architectural exercises to look for solutions to the issues identified. The city was the resource, and the questions asked were “what is it, how does it work, and why?”72 This process would help students realize that architecture and urban fabric are malleable and not “God-given.”73

In addition, the Centre worked as a community forum, with groups like tenants associations holding meetings and exhibitions in their space. It was also a teacher’s resource center, where new pedagogical methods could be tried. More importantly, however, the Centre was an archive of material about the urban environment, available for everyone to use and explore. After the first year, booking was needed, often a term in advance.74

An example of the Centre’s achievements was a self-built community center that sprung out of an urban trail and research project created by local children at the Edward Woods council estate. With the help of Webb and an architect, the community designed and constructed a building that was well used in the following years, completing the full urban studies learning process from awareness through to action.75

7.

In a city opened up to people, teaching materials which are now locked up in storerooms and laboratories could be dispersed into independently operated storefront depots which children and adults could visit without the danger of being run over.

—Ivan Illich76

The urban studies movement developed an educational network of spaces for built environment education across the UK operating outside the remit of the school. Urban Studies Centres made available learning resources for the community, including equipment, staff and information of the urban environment to assist people in their process of exploring and improving their local area. They offered a space for peer learning, where local professionals and community members could share their place-based knowledge with visitors and students. In some cases, the Centres also made mentoring accessible for people who needed help with their homes or gardens through community technical aid. Thus, the USCs covered the four approaches to learning proposed by Ivan Illich’s deschooling theory: reference services to educational objects, skill exchange, peer-learning, and guidance for incidental learning.77

In 1971, Illich explained that his idea in Deschooling Society was not to abolish schools, but rather to liberate schooling and “move control to socially organized grassroots movement.”78 Illich wanted the secularization of teaching and learning, diversifying who is allowed to educate others and multiplying the opportunities for education. Urban Studies Centres had a similar aim in taking built environment education outside of planning and architecture schools and making it accessible to all citizens. For Illich, “the best teacher of a skill is usually someone who is engaged in its useful exercise.”79 Who would be better to teach built environment education than built environment professionals themselves?

While there was no impact assessment or evaluation to determine what worked or not, the idea of an Urban Studies Centre has become relevant again today as new groups attempt to “deschool architecture” by taking architectural and urban education into the public realm and widen participation in the built environment.80 The interdisciplinary nature of the USC and its strong connection with then-current and past educational theory and practice was crucial by any measure of success, as well as Ward’s free rein and charismatic leadership. Ward was a unique figure, one capable of bridging the built environment with the fields of education and politics. Inspiring a wide array of practitioners, including architects, artists, geographers, planners, and teachers to work in urban environmental education, Ward also made an active effort to connect with a longer tradition of urban learning in Britain. We can learn from Ward, and from the Urban Studies Centres network, in that deschooling architecture not only has the potential to democratize city-making and offer built environment professionals a path to a more socially engaged way of practice. More importantly, it can help people “cherish their environment because it is theirs.”81

Ivan Illich, Deschooling Society (London: Marion Boyars Publishers Ltd, 1995), 32.

Ibid., 72.

Ibid., 80.

Ibid., 64.

George H Wood, “The Theoretical and Political Limitations of Deschooling,” The Journal of Education 164, no. 4 (1982): 370.

Gaylord Nelson, “The Gaylord Nelson Newsletter.” Gaylord Nelson Papers, November 1969.

Adam Rome, “The Genius of Earth Day,” Environmental History 15, no. 2 (2010): 194.

Colin Ward and Anthony Fyson, Streetwork: The Exploding School. Routledge & K. Paul, 1973: 7.

Colin Ward, “Art and the Built Environment,” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 1, no. 2 (1977): 89.

T. Harris, M. O’Brien Castro, Monia O’Brien Castro, Preserving the Sixties: Britain and the “Decade of Protest” (Springer, 2014), 4.

Roy Porter, London: A Social History (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1994).

Ellis Wasson, A History of Modern Britain: 1714 to the Present, 1st edition (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), 298.

Anne Power and Katherine Mumford, The Slow Death of Great Cities? Urban Abandonment or Urban Renaissance (York: YPS for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 1999), 70.

A third of the housing provision of the country—four million houses—were damaged by bombing. Wasson, A History of Modern Britain, 305.

Becky Tunstall and Stuart Geoffrey Lowe, “’Breaking up Communities’? The Social Impact of Housing Demolition in the Late Twentieth Century: Record of a Study and Information Sharing Day, 2 November 2012, York,” (York, UK: Centre for Housing Policy, 2012).

Power and Mumford, The Slow Death of Great Cities, 69.

Covent Garden Community Association and Coin Street Action Group are two well-known examples during the 1970s. Coin Street Public Inquiry was called “one of the longest, costliest, most important and most confused planning inquiries ever held in Britain.” Iain Tuckett, “Coin Street - There Is Another Way,” Community Development Journal 23, no. 4 (1988): 249–257.

Joan Kean, “Environmental Education for Community Action,” Children’s Environments Quarterly 6, no. 2/3 (1989): 60.

Lucy E. Hewitt, A Brief History of the Civic Society Movement (Civic Voice, 2014), 31, ➝.

Dennis Hardy, From New Towns to Green Politics: Campaigning for Town and Country Planning, 1946-1990 (Taylor & Francis, 1991), 120.

Joan, “Environmental Education for Community Action”: 60.

Hardy, From New Towns to Green Politics, 121.

Hugh R. Jones, “The Russell Report on Adult Education in England and Wales in the Context of Continuing Education.” Paedagogica Europaea 9, no. 2 (1974): 65–75.

The TCPA was initially set up in the 1890s to lobby for the implementation of garden cities in Great Britain. Later, in the post-war period, it became associated with a broader framework of town and regional planning. “Our History,” Town and Country Planning Association, ➝. See also Donald L. Foley, “Idea and Influence: The Town and Country Planning Association,” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 28, no. 1 (February 1962): 10–17.

Howard’s vision connected social reform with the environment, which permeated the activities of the association in the years to come. If town planning as a professional activity was located in the Royal Town Planning Institute, as a social movement, it was based at the TCPA. Foley, “Idea and Influence”: 10–17.

“Our History,” Town and Country Planning Association, ➝.

Catherine Burke and Ken Jones, eds., Education, Childhood and Anarchism: Talking Colin Ward (London and New York: Routledge, 2014), xviii.

Ibid., xxiv.

Interview with Anthony Fyson by Sol Perez Martinez, August 21, 2016.

Eileen Adams, Eileen Adams: Agent of Change: In Art, Design and Environmental Education (Loughborough Design Press Ltd, 2016), 29.

Council for Urban Studies Centres. Urban Studies in the 80’ : The Council for Urban Studies Centres’ 3rd Report (London, 1981).

Colin Ward and Anthony Fyson, “To the Reader. Explaining the BEE,” Bulletin of Environmental Education 1 (May 1971): 1.

Interview with Joan Kean by Sol Perez Martinez, November 25, 2016. BEE was first edited by Colin Ward from 1971 to 1979 at the TCPA, followed by Anthony Fyson from 1979 to 1980. Anne Armstrong, Graham Russell, and Liz Hirst took over until the mid-1980s and the publication closed in 1988, while Paul Rasmussen was the editor.

Brian Goodey, “Urban Studies in Search of a Future,” Bulletin of Environmental Education 61 (May 1976): 9.

However, Hart also criticized its bias towards the urban environment, claiming that the discipline was lacking a publication or center that balanced the natural and human-made in environmental education. Roger A. Hart, Children’s Participation: The Theory and Practice of Involving Young Citizens in Community Development and Environmental Care (Routledge, 1997), 79.

Catherine Burke, “’Fleeting Pockets of Anarchy’: Streetwork. The Exploding School,” Paedagogica Historica 50, no. 4 (July 2014): 433–442.

Including “Geography for the Young School Leaver,” “Art and the Built Environment,” and “Learning through Landscapes.”

Interview with Chriss Web by Sol Perez Martinez, August 26, 2016.

Illich, Deschooling Society, 64.

Anthony Fyson, “Education and Participation” in City Landscape: A Contribution to the Council of Europe’s European Campaign for Urban Renaissance (Elsevier, 1983), 155.

Skeffington Committee. People and Planning: Report of the Committee on Public Participation in Planning, HMSO, 1969.

Interview with Anthony Fyson by Sol Perez Martinez, August 21, 2016.

Ward and Fyson, Streetwork, 77–78.

Tony Champion and Peter Congdon, “An Analysis of the Recovery of London’s Population Change Rate,” Built Environment 13, no. 4 (1987): 193.

“Urban Studies Centres – Educational Focus for European Architectural Heritage Year 1975,” Bulletin of Environmental Education, 34 (February 1973): 9.

Ibid., 10.

Ibid.

A contemporary voluntary organization with similar aims that took the opposite approach to the USCs was Inter-Action directed by Ed Berman. He fundraised to create the first purpose-built arts community center in Britain designed by Cedric Price. A year before it was finished, Berman said in a RIBA conference that he regretted his decision and he recommended using abandoned properties. “Art without Architecture,” Architect’s Journal, April 21, 1976, 771. See also “Urban Studies Centres,” Bulletin of Environmental Education: 10.

Colin Ward, “The Outlook Tower, Edinburgh: Prototype for an Urban Studies Centre,” Bulletin of Environmental Education, December 23, 1973.

Geddes, as well as Peter Kropotkin, were regular references for Ward’s work. Both men were interdisciplinary thinkers with an anarchist outlook. Colin Ward, Influences: Voices of Creative Dissent: Quiet Voices of Dissent, 1st edition (Green Books, 1991).

Patrick Geddes, Cities in Evolution: An Introduction to the Town Planning Movement and to the Study of Civics (London: Williams, 1915), 287.

Keith Wheeler, in Dennis Hardy, From New Towns to Green Politics: Campaigning for Town and Country Planning, 1946-1990 (Taylor & Francis, 1991), 129.

Ward and Fyson, Streetwork, 72.

Ward and Fyson, Streetwork, 5.

J.M. Higson, “Introducing CUSC – the Council for Urban Studies Centres,” Bulletin of Environmental Education, February 22, 1973.

Ward and Fyson, Streetwork, 10.

Anthony Fyson, “News of CUSC – Council for Urban Studies Centres,” Bulletin of Environmental Education, March 23, 1973.

Anne Armstrong, Graham Russell, and Liz Hirst, Council for Urban Studies Centres. State of the Art Report (Town and Country Planning Association and Streetwork Ltd, 1984).

Hart, Children’s Participation, 79.

Jeff Bishop, Eileen Adams, and Jean Kean, “Children, Environment and Education: Personal Views of Urban Environmental Education in Britain,” Children’s Environments 9, no. 1 (1992): 49–67.

Myrna Margulies Breitbart, “Inciting Desire, Ignoring Boundaries and Making Space: Colin Ward’s Considerable Contributions to Radical Pedagogy, Planning and Social Change,” in Education, Childhood and Anarchism: Talking Colin Ward (London, New York: Routledge, 2014).

Colin Ward, The Child In The City (New York: Penguin Harmondsworth, 1979), 199.

Chris Webb, “Politics and Participation in London Planning,” Seminar paper, March 17, 1981.

“Guide to Records. Notting Dale Urban Studies Centre c.1900-2001,” North Kensington Community Archive.

“Notting Hill Urban Study Centre,” The Harrovian, July 5 1975.

Interview with Chris Webb by Sol Perez Martinez, August 26, 2016.

Chris Webb, Notting Dale Urban Studies Centres. Annual Report 1975-1976 (London: Notting Dale Urban Studies Centre, August 1976).

Ibid.

All of these methods were also advocated by Ward in BEE and in his public lectures, one of which Webb attended.

Webb, Notting Dale Urban Studies Centres. Annual Report 1975-1976.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Interview with Chris Webb by Sol Perez Martinez, August 26, 2016.

Interview with Joan Kean by Sol Perez Martinez, November 25, 2016.

Illich, Deschooling Society, 84.

Illich, Deschooling Society, 78–79.

Rosa Bruno‐Jofré and Jon Igelmo Zaldívar, “Ivan Illich’s Late Critique of Deschooling Society: ‘I Was Largely Barking Up the Wrong Tree,’” Educational Theory 62, no. 5 (2012): 577.

Ivan Illich, After Deschooling, What? (London: Pluto Press, 1987), 23.

For example the Urban Rooms Network, Liveworks by Sheffield University, The Civic School by public works and the Mobile Museum by Verity Jane Keefe, among others. In Sol Perez-Martinez, Urban Rooms, Civic Schools and Urban Learning, exhibition brochure, Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London, 2018.

Ward and Fyson, Streetwork, 3.

Architectures of Education is a collaboration between Nottingham Contemporary, Kingston University, and e-flux Architecture, and a cross-publication with The Contemporary Journal.