The beginning of the twentieth century in England saw an increase in social welfare and educational reforms, the birth of the Garden City movement, and the experimental Open Air School movement. These efforts were triggered by the problems of mass urbanization and the overcrowded, poor living conditions in the industrial towns and suburbs of the North and across the country.

This time also saw a fresh approach towards education, which would reshape traditional forms of education based on the total authority of the teacher, discipline, and obedience.1 Progressive ideas about education in the UK during the last decade of the nineteenth and into the early twentieth century manifested in a series of private experimental schools and culminated in the rise of global educational networks concerned with the development of progressive ideas in education and the liberalization of the child.2 The World Education Fellowship, for instance, which held influential conferences between 1921–1938, focused on “child-centered education, social reform through education, democracy, world citizenship, international understanding, and the promulgation of world peace.”3

It is within this context that David and Mary Medd worked on the intersection between architectural design and education. The Medds worked in postwar England; a time of optimism and experimentation, when governments “increased their commitment to the building or renewal of democracies through public schooling.”4 Yet it was also a time of austerity with limited materials, rationing, and labor-shortages. Postwar, bomb-damaged Britain was urgently in need of rebuilding. The haste with which cities were being (re-)built provided fertile conditions for the Medds to develop a body of work described as “humane functionalism,” one that greatly influenced subsequent thinking regarding design for education in the UK.5

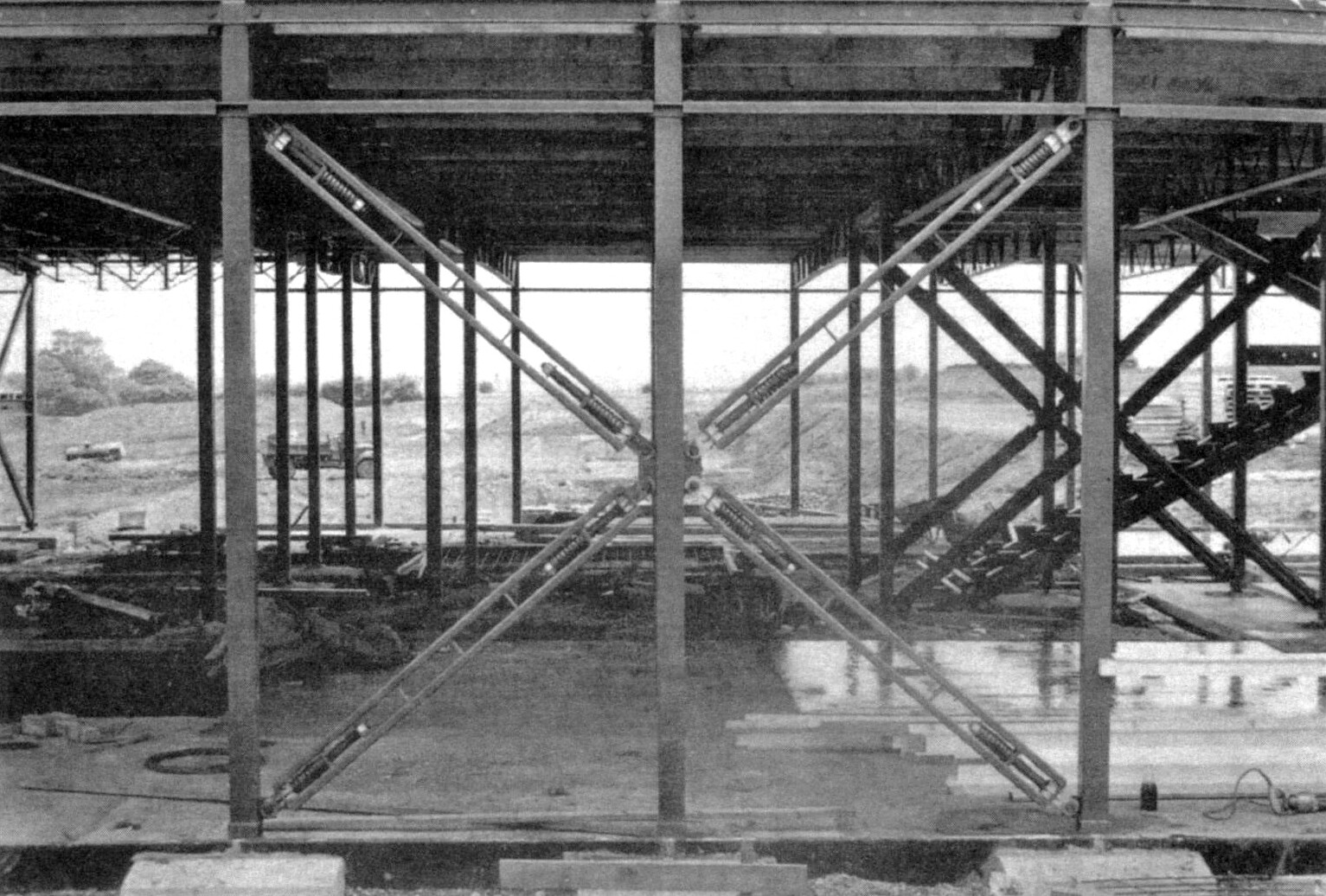

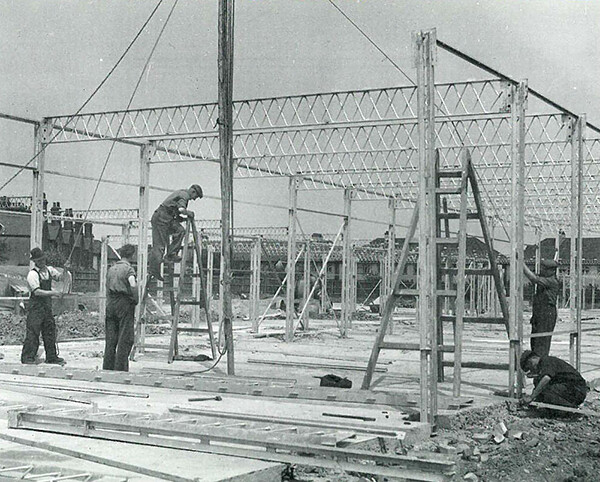

Burleigh Junior School under construction. Source: Andrew Saint, Towards a Social Architecture (1987). © Department for Education.

The Hertfortshire Schools

Both Mary and David joined the Architects Department of Hertfordshire County Council directly after the war. Under the leading influence of Stirrat Johnson Marshall, Hertfordshire was pioneering in the design and production of prefabricated school buildings. Using fast building methods and working with tightly rationed materials and budgets, the council was able to rapidly construct a large number of new schools for an exploding population.

David was instrumental in the technical design of the council’s new school buildings, which were based on a standardized, pre-fabricated set of steel components originally manufactured by Hills and Company for housing in the 1920s. Their delicate metal structure was exposed internally, and together with large areas of glazing, generated a “lightness in spirit,” which was very different to the traditionally heavy, closed, brick Victorian schools.6 Special attention was given to the details and fittings, and every component in the buildings was specifically designed, down to the light fittings.7

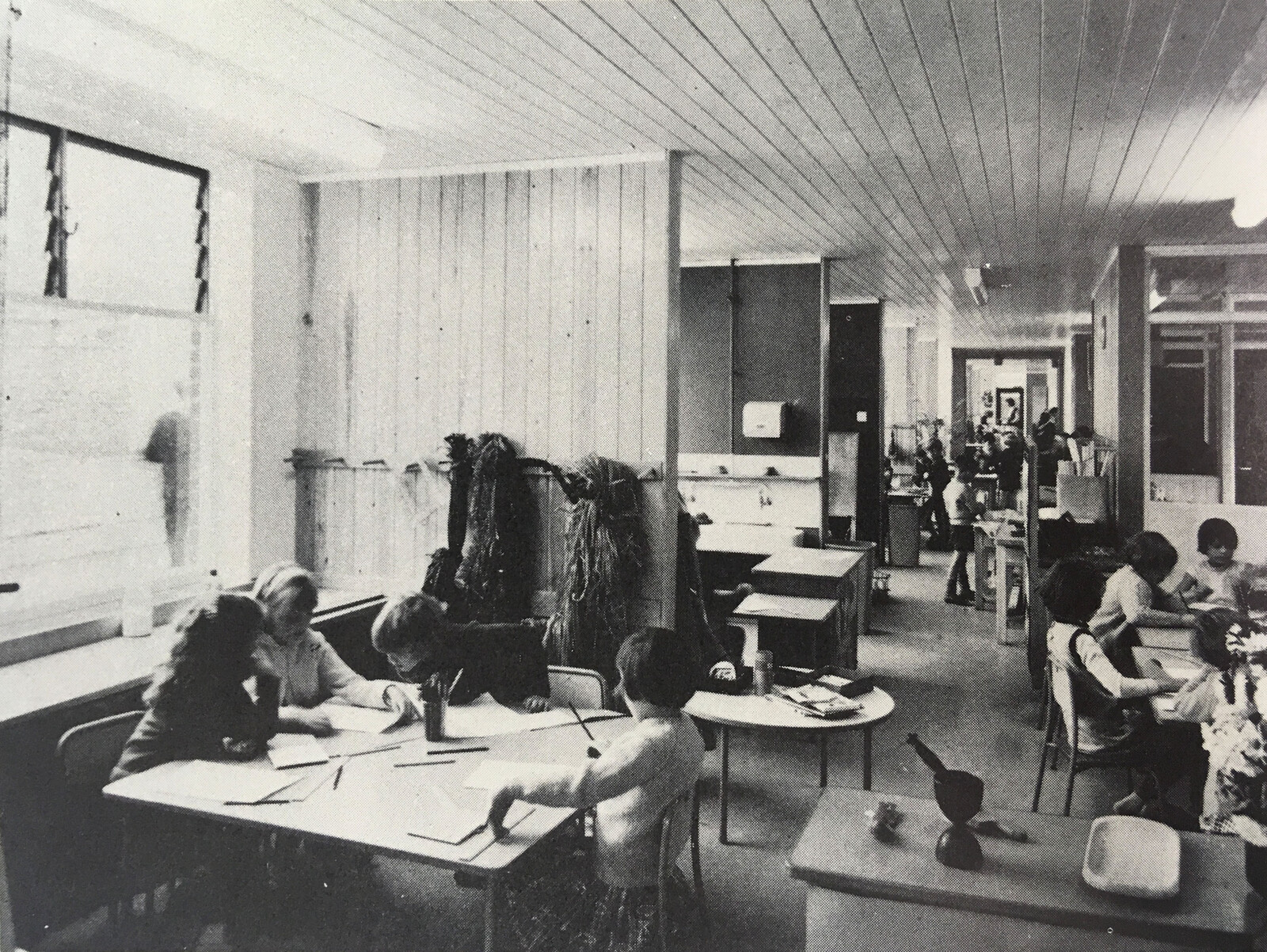

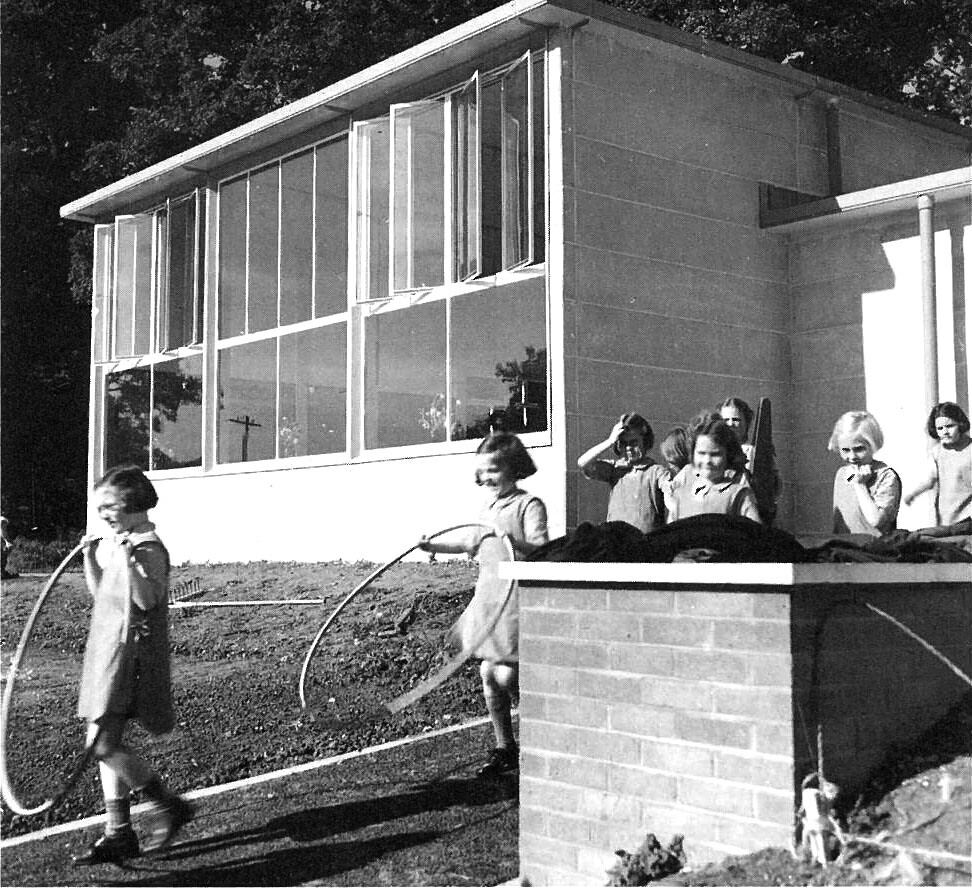

David and Mary Medd, Burleigh Infants School, Cheshunt, 1949. © Kristin Trommler & Aoife Donnelly.

David and Mary Medd, Essendon Primary School, Essendon, 1948, typical classroom. © Architectural Press Archive/ RIBA Collections.

Infants spilling out of their classroom at Essendon Primary School. Source: Andrew Saint, Towards a Social Architecture (1987). © Department for Education.

David and Mary Medd, Burleigh Infants School, Cheshunt, 1949. © Kristin Trommler & Aoife Donnelly.

Two main influences shaped the design of the early Hertfordshire schools. The first was the Henry Morris Cambridgeshire community village colleges from the 1930s; a progressive educational model where a school is combined with a community center, bringing education into the daily lives of the community it served.8 The second was the purpose-built experimental designs of Open Air schools. Part of a European-wide movement from the beginning of the twentieth century to tackle the spread of infectious diseases like tuberculosis in overcrowded city environments, these schools were built in areas away from city centers. They focused on making connections with outdoor environments through flexible walls to allow for maximum exposure to fresh air. Educationally, they recognized the role of nature and the outdoor world in the development of children, and focused on a balance between body, hands, and mind.

The layout of the Medds’ early Hertfortshire schools didn’t support progressive teaching practices; they were still based on self-contained classrooms. However, the architecture was tailored to the scale of the child, with low window sills to see out of, lightweight furniture easily moveable by children, connection to the outdoors in each classroom, and decorative arts integrated into the design for stimulating intellectual development. The Hertfortshire schools allowed for guiding principles to be established for a child-centered school design that was further developed by Mary in the following decades. “Schools had to be broken up in bulk and not look industrial… Children should be able to see out of windows… The main entrance of the school should be used by children as well as adults.”9

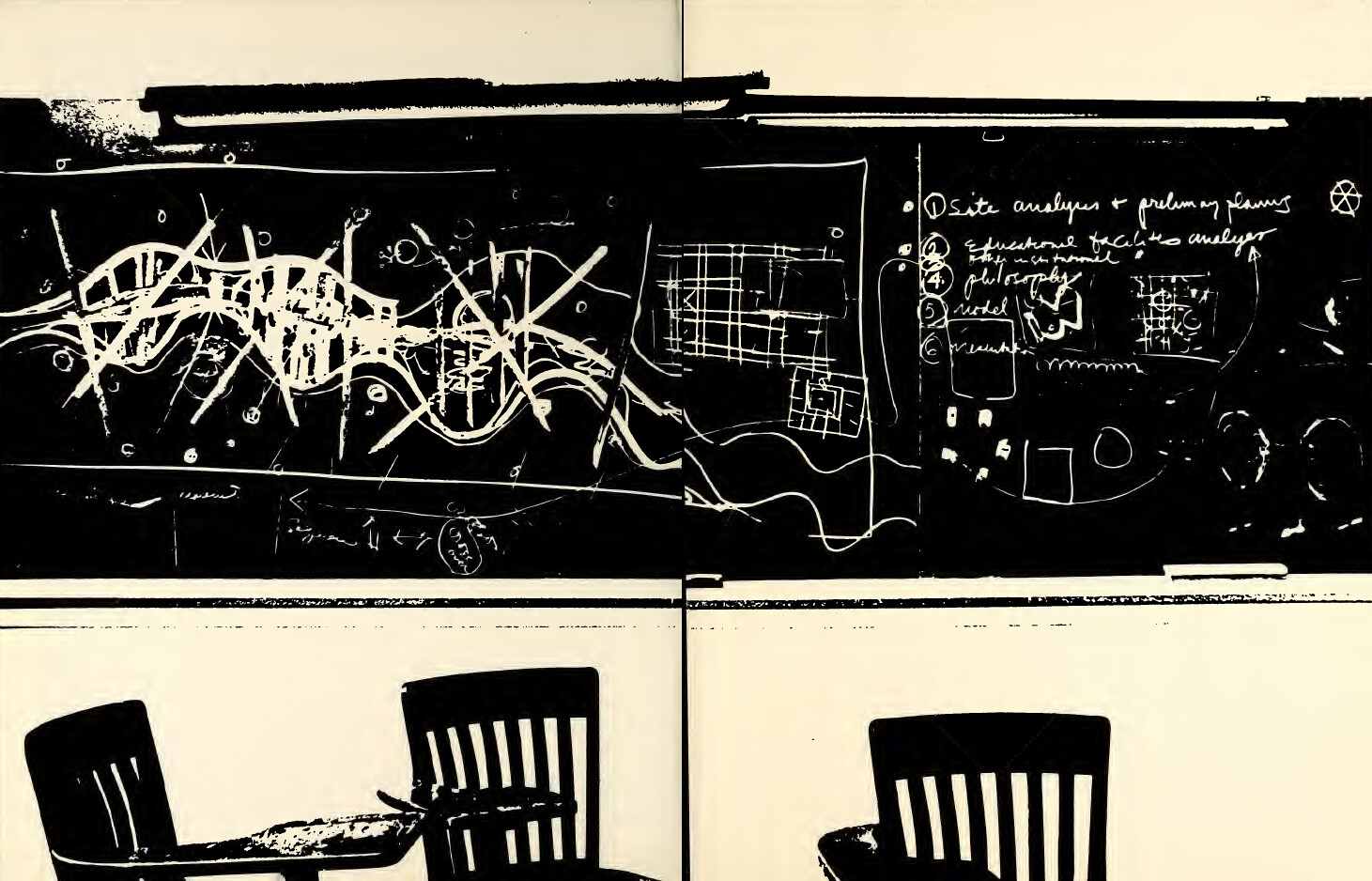

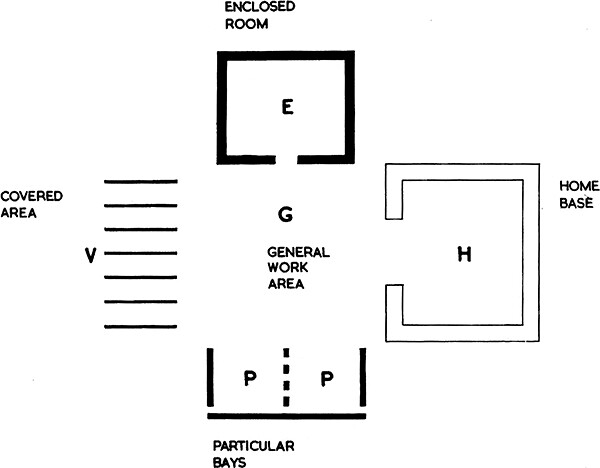

David and Mary Medd, Ingredients of Planning, diagram. Source: Institute of Education Archive, ME/M/10/2.

Planned Environment of Opportunities

Working later for the Architects & Building Branch of the Ministry of Education, the Medds developed a new democratic typology for education. Their “planned environment of opportunities” consisted of a variety of different, flexible and connected spaces, designed with the intention to support constantly evolving best practices in teaching, and stood in direct opposition to the prevailing classroom-corridor model.10

Key to the development of their model was a 1959 visit the Medds paid to the Crow Island School in Winnetka, Illinois (built 1940), a progressive public elementary school designed by Perkins, Wheeler, and Will in collaboration with Eliel Saarinen. The design of the building was regarded as highly influential and demonstrated how to combine a variety of different spaces. Classrooms consisted of a conventional teaching area and a workshop section for practical and creative work, an essential component of the curriculum. Also new was the integration of the domestic and homely character of the environment, featuring “a library, sitting room with bed and fireplace and cooking area.”11

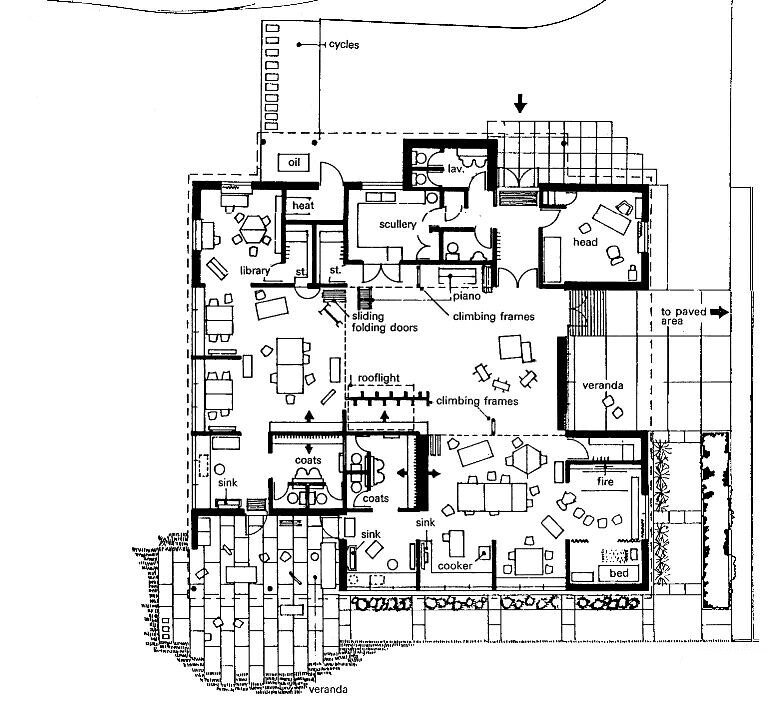

David and Mary Medd, Finmere School, Finmere, 1959, plan. Source: Institute of Education Archive, ME/Z/5/2/150.

After visiting Crow Island, the Medds developed their “5 ingredients for design in primary school planning”: the home base, the particular bays, the covered area or veranda, the general work area, and the enclosed room.12 First realized in the design for Finmere Village school, Oxfordshire (1958-1959), a single-story arrangement of clustered spaces forming a learning community, from then onwards, this model was applied to numerous developments by the A&BB that were either produced by the Medds or or influenced by their approach.

The Medds tirelessly continued their approach of combining research into the process of school design and testing it in practice. Every new school they built was an investigation into another topic, and the next school would be built upon the findings of the previous one. This evolving knowledge was disseminated through Building Bulletins, a documentation and evaluation made following each completed school and made available to local authorities across the country.

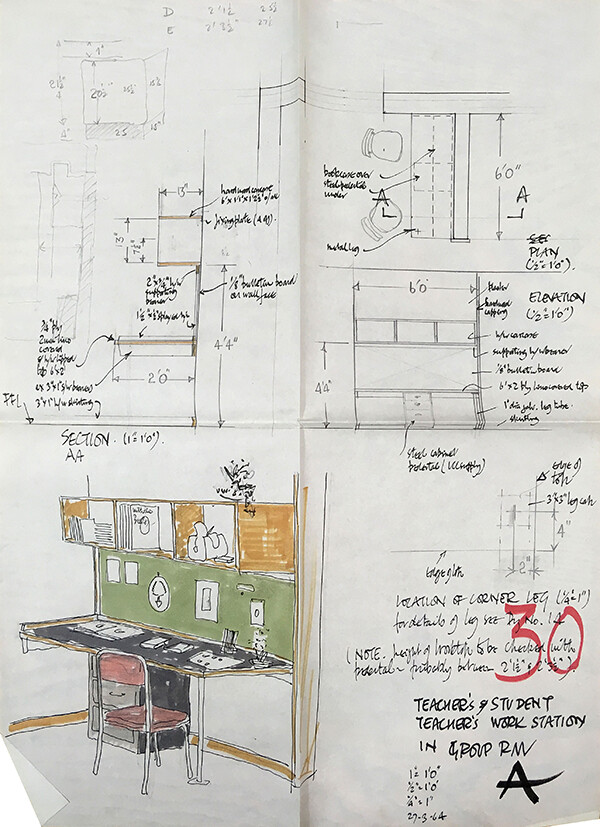

David Medd, Evelyn Lowe detailed interior study of teachers work station. Source: Institute of Education Archive, ME/E/7/28.

Evelyn Lowe: Built in Variety

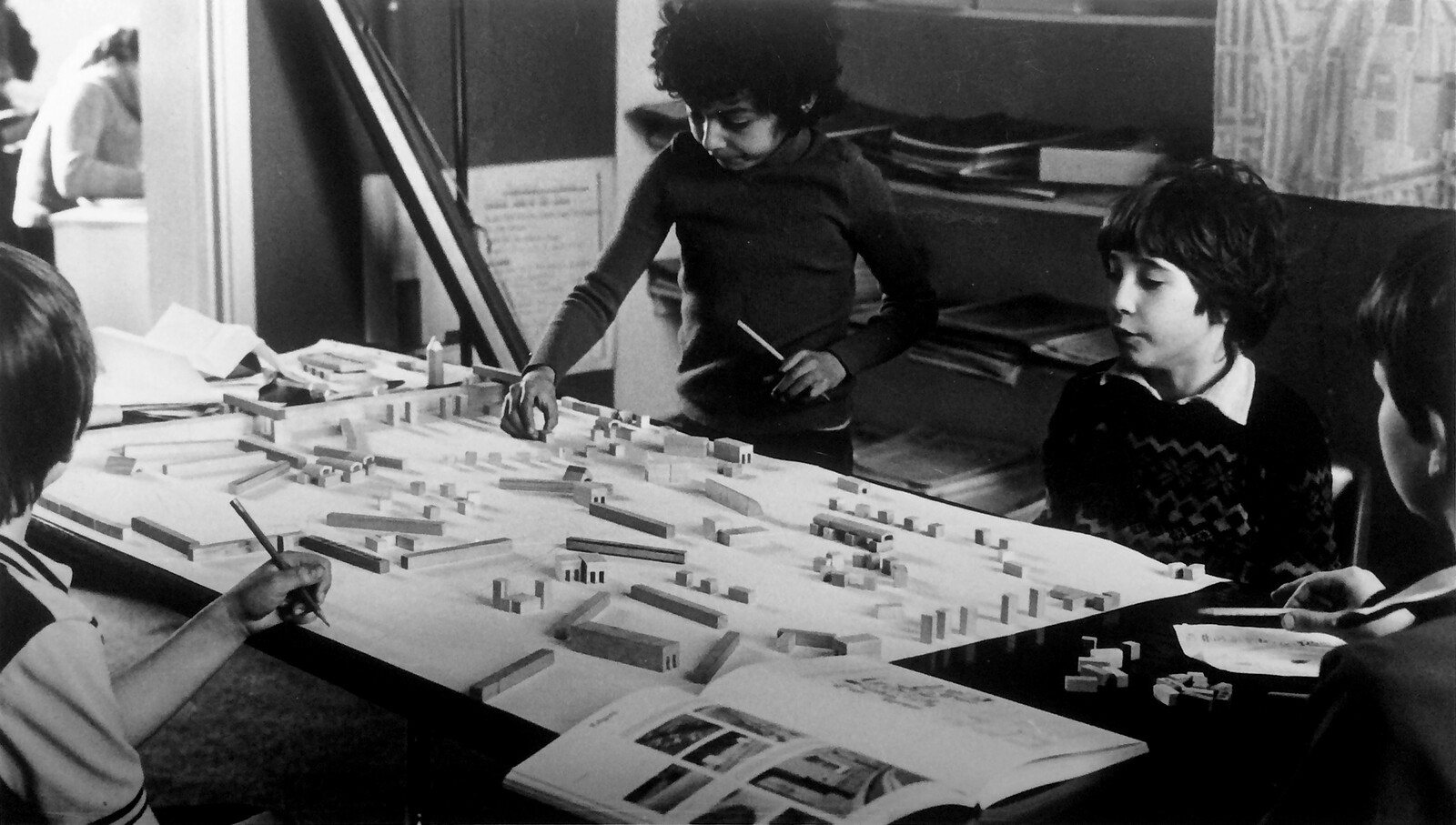

It was understood amongst designers, policymakers, and educators alike at the time that the needs of parents and children in a dense urban environment were very much the same as those dwelling in a village context. Evelyn Lowe, which the Medds designed following Finmere, sought to turn an institutional block “into a small village, that a child can wander around without being aware of the whole.”13 Employing techniques such as a low picket fences and a single-story arrangement—recalling the scale of a home environment—the project sought to draw parents and families into the site, including out of hours, and bridge the gap between the community beyond and the inner life of the school.

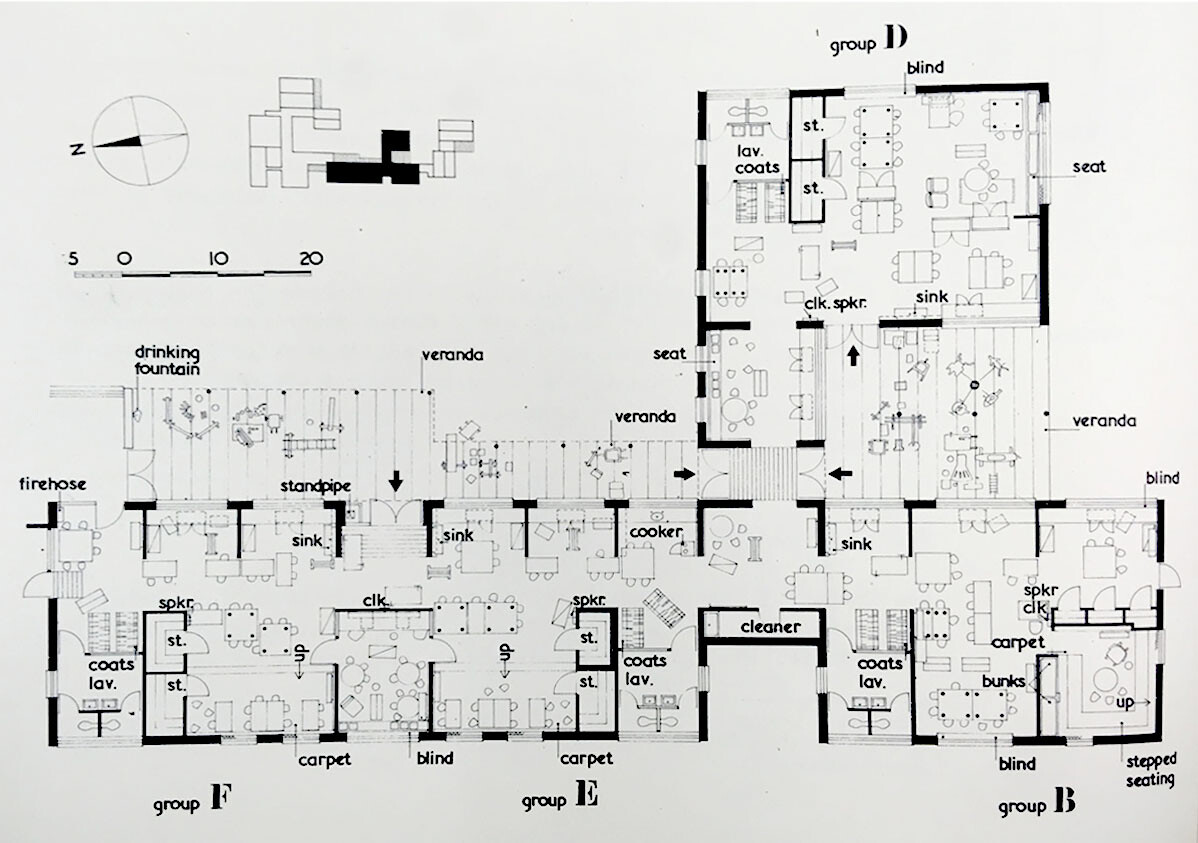

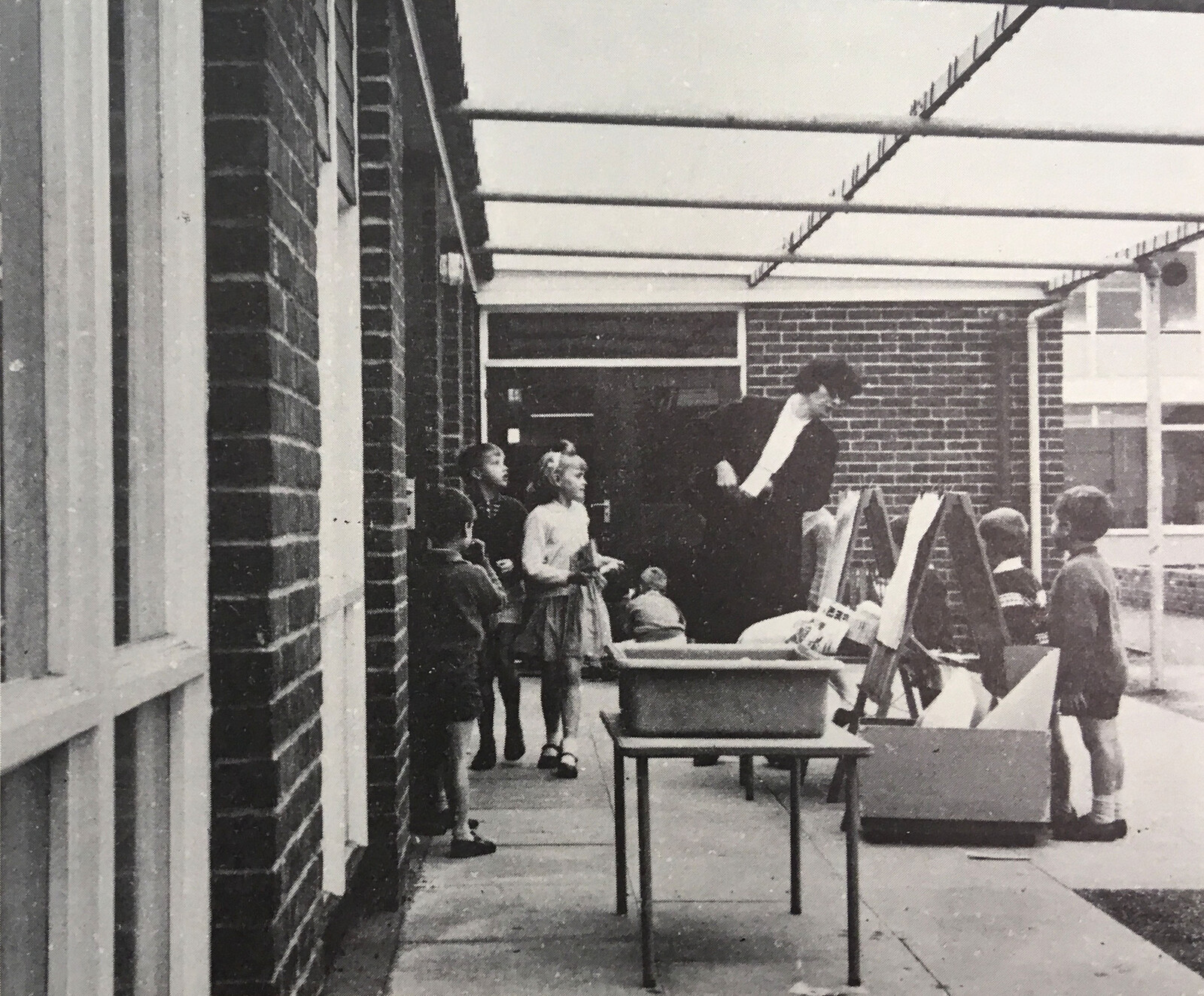

Situated within an inner South London context of major post-war infrastructural change and large-scale housing development, Evelyn Lowe was built on the site of a World War II bomb-damaged, two-story school that had to be demolished. The school itself appeared rather pedestrian from the exterior, resonating with the desire to create a modest and humanist architecture focused on being a vehicle for education. Each of the five “ingredients” established at Finmere were present at Evelyn Lowe. The school gravitated around an inner courtyard, allowing a separation from surrounding busy roads. The flow from external to internal spaces was a critical part of the project, with an inherent flexibility generated through a perforated and open elevational treatment, creating an ease of movement and access to the designed landscape that harnessed nature and the elements.

Integration of the arts was a key principle of the Medds model, not simply in support of core curriculum, but “as a means to growth and intellectual development.”14 Within a setting designed as a prepared landscape for learning, natural and man-made triggers allowed sketching and drawing to become crucial pedagogical methods, considered ways of investigating and researching, as well as communicating and producing imaginative work. Children could pursue art or making activities individually or in small groups, with the architecture supporting this through the particular bays and the home base spaces.

Evelyn Lowe detail plan (groups B, D, E, and F) and key plan. Source: Eveline Lowe Primary Building Bulletin no. 36, 1967, Institute of Education Archive, ME/R/3/36. © Department for Education.

Evelyn Lowe exterior, view from the internal court. Source: Eveline Lowe Primary Building Bulletin no. 36, 1967, Institute of Education Archive, ME/R/3/36. © Department for Education.

Evelyn Lowe interior, link between rooms D and B. Source: Eveline Lowe Primary Building Bulletin no. 36, 1967, Institute of Education Archive, ME/R/3/36. © Department for Education.

Evelyn Lowe exterior, view of veranda serving as outdoor classroom. Source: Eveline Lowe Primary Building Bulletin no. 36, 1967, Institute of Education Archive, ME/R/3/36. © Department for Education.

Evelyn Lowe detail plan (groups B, D, E, and F) and key plan. Source: Eveline Lowe Primary Building Bulletin no. 36, 1967, Institute of Education Archive, ME/R/3/36. © Department for Education.

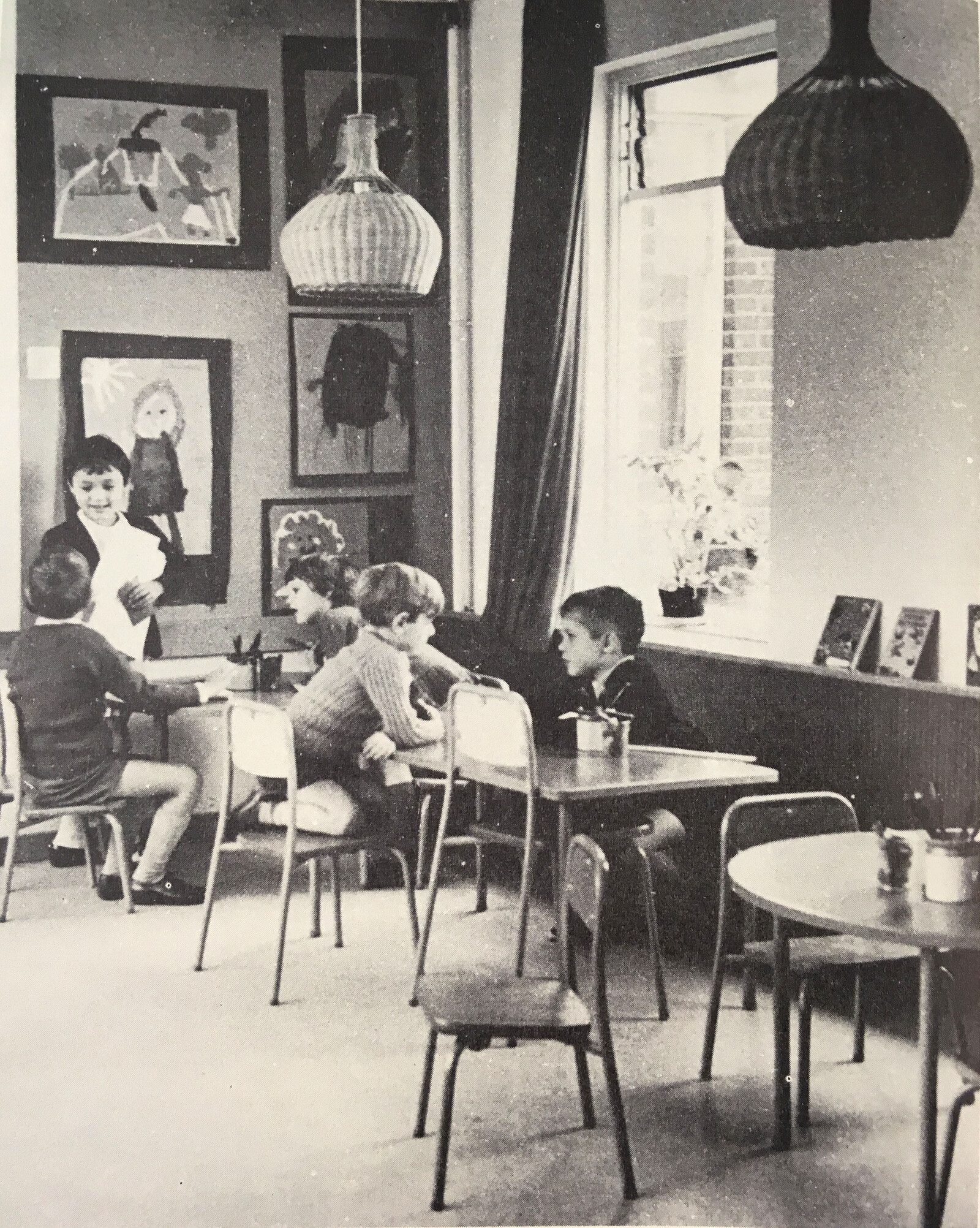

Meticulous care was taken in composing the interior, from attention to color, selection of materials and finishes, and detailed design in support of the proposed range of learning activities and varying scales of groups. The school community would gather around focal activities. Eating the school lunch was not just a functional activity but a part of the child’s social education, and the architecture created intimate, welcoming domestic scale settings to allow this. The piano in the music bay was considered a common activity and central to the life of the school community, with loose furniture, beautiful floor and wall finishes, and lighting supporting this.

At Evelyn Lowe there was a conscious move to design a flexible and more open classroom that could support progressive teaching models. This was in line with the 1967 “Plowden” report published by the Central Advisory Council for Education (England), which proposed abandoning traditional classroom structures and highlighted the importance of the role of parents and the school environment. The structure of the classes and teacher pupil ratio at Evelyn Lowe was based on that defined by the Inner London Education Authority, with fourteen children to one teacher, and was supported by education students to improve the ratios. Staff worked closely as a team, sharing preparation and setting up activities to support children collectively.

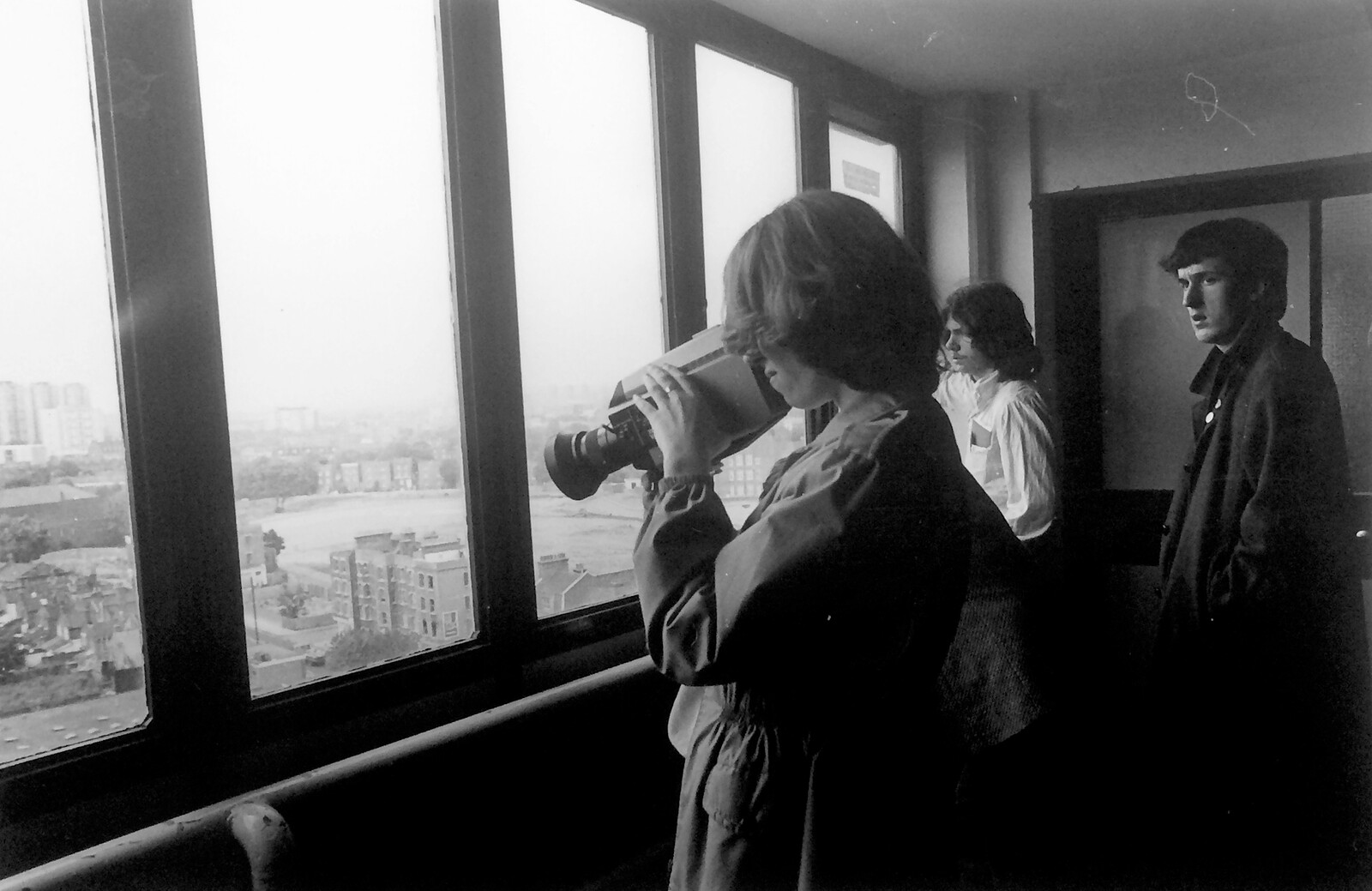

A documentary produced at the time by BBC titled “Expanding the Classroom,” noted that at Evelyn Lowe, it appeared there was little formal learning going on, and asked if this was “anarchy in action in the classroom.”15 In response, teachers observed that all learning was founded in interest, identifying that there was purpose evident in all that the children undertook. The “prepared landscape for learning” approach set out to suggest opportunities for the children to investigate in a self-lead way. Part of the research that fed into this method was based on establishing how much freedom children could take without feeling fear. This was built into the design through the scale, variety, and character of spaces, together with the distances for surveillance by teachers, which was determined on the basis of careful observation of children at play.

The Thatcher Revolution in Schools: “A Profession Brought to Heel”

Subsequent shifts in government, approach, and ambition coupled with a changing social and economic context ended the golden era of post-war school design in England. Margaret Thatcher, who served as Minister of Education from 1970–1974, clashed with the educational establishment at the time. Once in power as prime minister, she introduced “profound change in the ecology of education,” heralding the beginning of a new regime in education.16

With a shift in emphasis away from progressive child-centered education models to a more military style approach to education, teachers ultimately lost control of the classroom in terms of curriculum, design, and use of space. Architecturally, the introduction of the National Curriculum in 1988 resulted in locking down spatial opportunities and a return to the former hegemonic classroom model that the Plowden era schools had attempted to move away from.

The process of erosion of progressive values in public sector schooling, which began in the 1970s with Thatcher, has resulted today in an educational system far from what the Medds sought to support through their work. According to Michael Fielding and Peter Moss, the neoliberal agenda for education, which focuses on standardization, results, ratings, and increasing competition between schools, “impedes education’s ability to work with new and important understandings of children, knowledge and learning, which emphasize diversity and complexity.”17

Tightening regulation in school design coupled with today’s political context of austerity has effectively eliminated the opportunity for schools to make significant structural or curricular changes from within. With the annulation of the Building Schools for the Future program in 2010, building new or extending existing public sector schools in the UK is limited.18 Between 1950–1970, teachers could author both the content of the school curriculum and their method of delivering it. “By contrast now a range of external influences dictates the nature of the experience—measurable outcomes and answerability of schools and individuals within them to parental and government pressure.”19

Public education is a collective task, “a subject of civic interest and a responsibility of all citizens: the public in public education.”20 Faced with a crisis in terms of the climate emergency as well as the global rise of nationalism and individualism, emphasis in school design needs to return to becoming a more collective endeavor, focused on the creation of “caring” communities.21 Michael Fielding’s question remains of “how might we develop a radical education with democracy as a fundamental value and the common school as a basic public institution in a truly democratic society?”22

A common undercurrent in progressive educational thinking and associated architectural models are the core principles of the rights of the child.23 What these approaches have in common is the mutual desire to support the natural inquisitiveness of childhood by spatially providing for the multiple possibilities of learning. As Colin Ward advocates, “in the ideal city, every school would be a productive workshop and every workshop an effective school.”24 Perhaps it is time to revisit the humane functionalism of the Medds, where architecture might again acknowledge that “children are the basis of school design.”25

Kevin J. Brehony, “A new education for a new era: the contribution of the conferences of the New Education Fellowship to the disciplinary field of education 1921–1938,” Paedagogica Historica 40, issue 5-6 (2004): 1.

See New Ideals in Education (NIIE) conferences 1914–1937, New Education Fellowship (NEF) conferences 1921–1938, and World Education Fellowship (WEF) founded 1921.

“World Education Fellowship: An introduction,” UCL, Institute of Education LibGuides, ➝.

Catherine Burke, A Life in Education and Architecture: Mary Beaumont Medd (London and New York: Routledge, 2016), 211.

Geraint Franklin, “’Built-in variety’: David and Mary Medd and the Child-Centred Primary School, 1944–80,” Architectural History 55 (2012): 321–367

Burke, A Life in Education and Architecture, 80

Nikolaus Pevsner described the early Hertfordshire schools as “elegant and carefully considered into the smallest detail.” Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Hertfordshire (London: Penguin Books, 1953) as cited in Burke, A Life in Education and Architecture, 82

Henry Morris Cambridgeshire community village colleges were described by Andrew Saint as “the most prophetic expression of what a ‘community school’ might mean.” Andrew Saint, Towards A Social Architecture: The Role of School-Building in Post-War England (London and New Haven, Yale University Press, 1987), 41. Architecturally, the best known example is Impington Village College (1938–1940), designed by Walter Gropius and Maxwell Fry. What matters here is “the sense of congruity between form and social intention: the relaxed groupings of classrooms, community space and shared hall.”

Saint, Towards A Social Architecture, 80.

Burke, A Life in Education and Architecture, 122

Building Bulletin no. 18 (London: HMSO, 1961), 45, as cited in Burke, A Life in Education and Architecture, 187.

Burke, A Life in Education and Architecture, 214.

Interview with David Medd, in Principles of Primary School Design: From the Past to the Future, eds. C. Burke, P. Cunningham, A. Clark, D. Cullinan, R. Sayers, and R. Walker (London: Fielden, Clegg and Bradley, 2010).

Burke, A Life in Education and Architecture, 121.

BBC, The Expanding Classroom, dir. Eileen Moloney, April 20, 1969.

Peter Wilby, “Margaret Thatcher’s education legacy is still with us – driven on by Gove,” The Guardian, April 15, 2013, ➝.

Michael Fielding and Peter Moss, “Radical Democratic Education,” Submission to American Sociological Association, 107th ASA Annual Meeting (April 4, 2012), 2, ➝.

A Labour government’s ambitious school building program was cancelled by Michael Gove on his appointment as Minister of Education.

Geoffrey Sherington, “The death of progressive education: How teachers lost control of the classroom, by Roy Lowe” Journal of Educational Administration and History 42, no. 1 (2010): 100–101.

Fielding and Moss, “Radical Democratic Education,” 1, ➝.

Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality (New York: Harper & Row, 1973).

Fielding and Moss, “Radical Democratic Education,” 2, ➝.

The UN Convention of the Rights of the Child—the first comprehensive human rights treaty for children—states that children have the right to express their views “in all matters affecting the child” and that the views of the children should be given “due weight.” This involves the right to be consulted on their environment. See ➝.

Colin Ward, The Child in the City (London: London Architectural Press, 1977), 182.

David and Mary Medd, Building Bulletin no. 1 (1949).

Architectures of Education is a collaboration between Nottingham Contemporary, Kingston University, and e-flux Architecture, and a cross-publication with The Contemporary Journal.

Subject

This contribution derives from a presentation given at Nottingham Contemporary on November 8, 2019. A video recording of the presentation is available here.

Architectures of Education is a collaboration between Nottingham Contemporary, Kingston University, and e-flux Architecture, and a cross-publication with The Contemporary Journal.