Dimensions of Citizenship is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the United States Pavilion of the 16th International Architecture Exhibition at La Biennale di Venezia, commissioned by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the University of Chicago. The project approaches the relationship between architecture and citizenship through essays reflecting a series of telescoping scales: Citizen, by Adrienne Brown; Civitas, by Ana María León; Region, by Imre Szeman; Nation, by Dan Handel; Globe, by Jennifer Scappettone; Network, by Ingrid Burrington; and Cosmos, by Nicholas de Monchaux. Responses to current events will be published over the course of the Biennale by Javier Arbona and Bryan Finoki, Sukjong Hong, Kian Goh, Enrique Ramirez, and Mabel O. Wilson.

[O]ne irony of late modern walling is that a structure taken to mark and enforce an inside/outside distinction—a boundary between “us” and “them” and between friend and enemy—appears precisely the opposite when grasped as part of a complex of eroding lines between the police and the military, subject and patria, vigilante and state, law and lawlessness.

—Wendy Brown, Waning Sovereignty, Walled Democracy (2010)

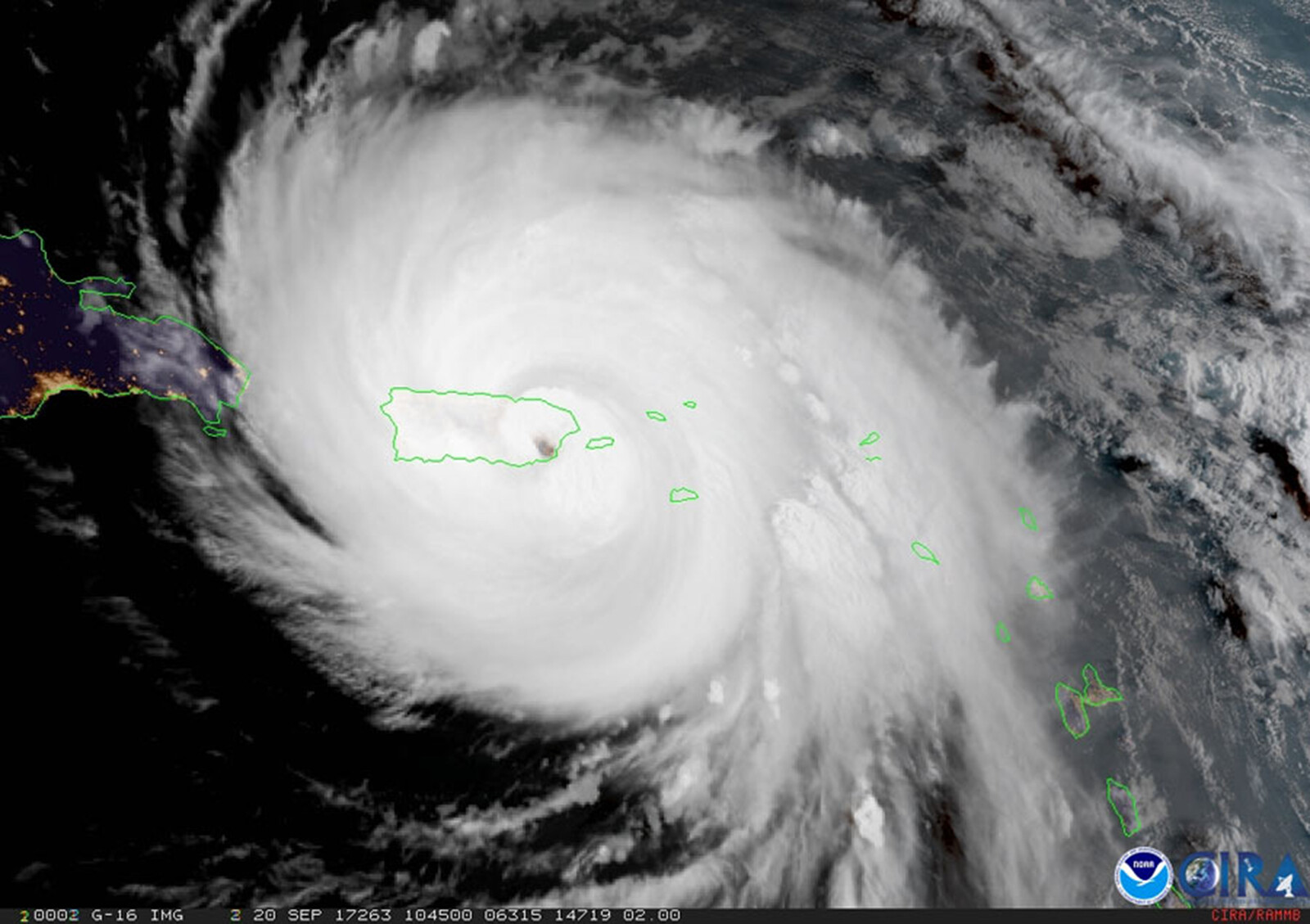

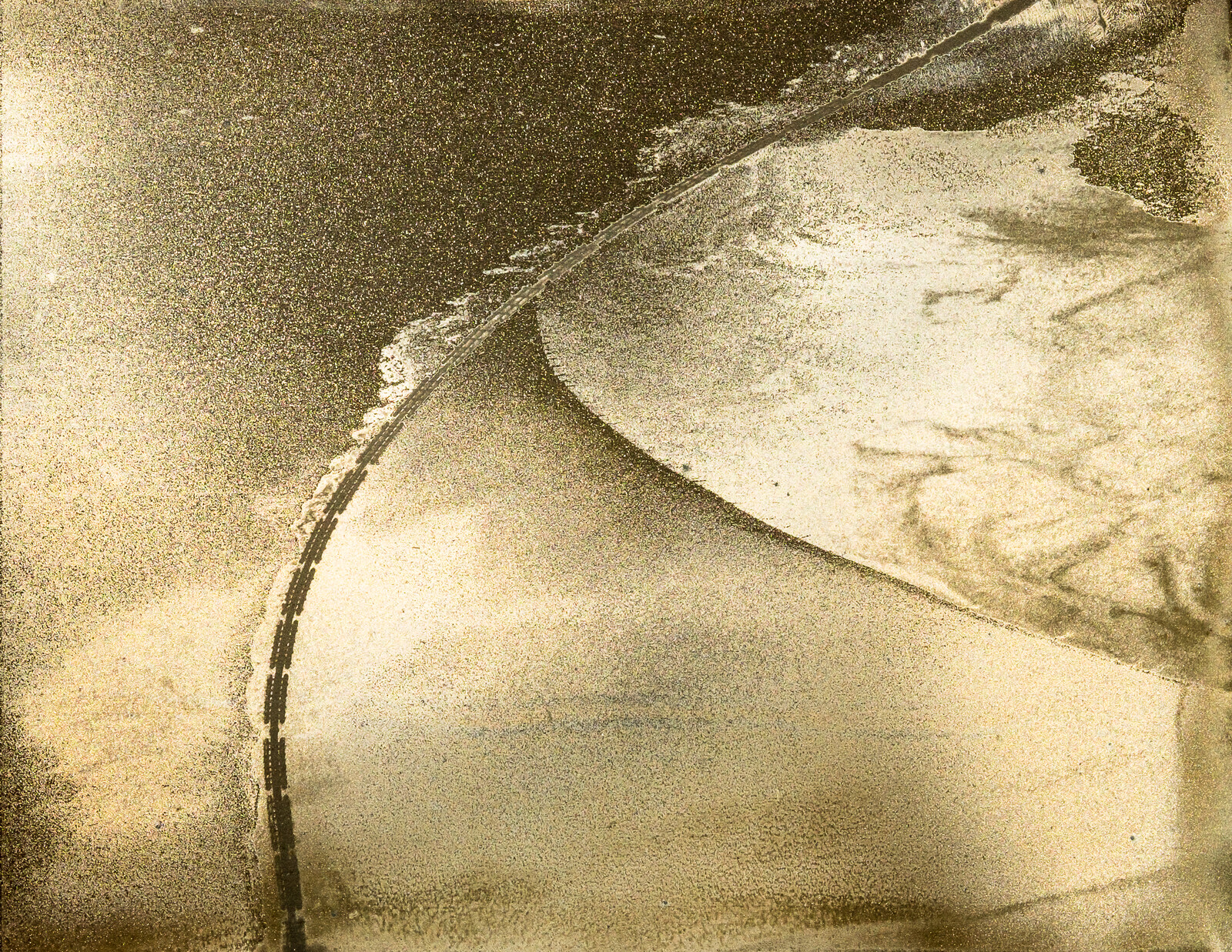

Paradox is at the heart of the relationship between architecture and citizenship. For every act of fortified inclusion and exclusion, there is a counter, perhaps informal or subversive, act that strives to undermine distinctions. Border walls are the default architectures that describe nationhood, but also just one of many architectural expressions of citizenship. The US-Mexico border on the west coast, for example, reveals its existence within conditions of increasingly “blurred distinctions.” The militarized wall disrupts social and economic bilateral exchanges and pollutes the natural watershed of the Tijuana River. The very architecture of this symbol of nation is constructed from steel fencing and technologies procured from around the globe.

Brown calls border walls across the world “an ad hoc global landscape of flows and barriers,” and the recognition of this conjoined condition is important as we apply the lessons of the border to less overt sites. Paradoxes of belonging are everywhere we look: airports, bathrooms, Starbucks coffee shops. Citizenship has never been constituted as a singular, monumental edifice, reducible to any one institution of power or construction of identity. As a cluster of rights, responsibilities, and attachments, the lived experience of citizenship speaks to the plural, complex, and intimate relations we have with the actual and virtual spaces we inhabit.

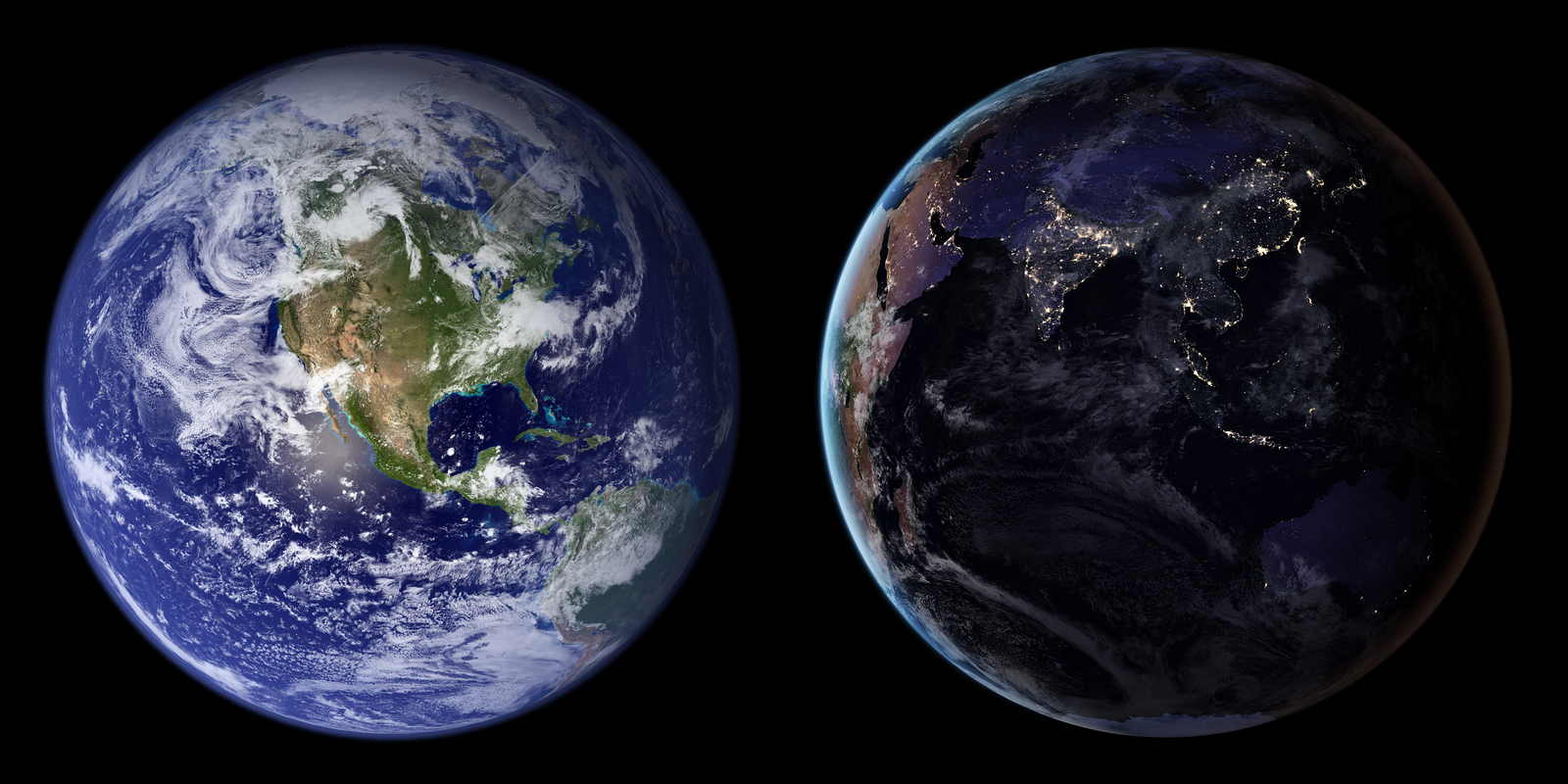

While 2018 is a moment when ideologies are most vociferously cast in binary rhetoric, the lived experience of citizenship today is rhizomic, overlapping, and distributed. Paradoxical forms of citizenship comprise twentieth century aspirations of the “global village” and the current and unavoidable impact of such globalization: the violence of forced expulsions and transnational capital manifested in refugee camps or free-trade zones. Informal or subversive acts operate on a smaller scale, bringing us together in old and new ways that may defy or enforce outmoded divisions and segregations, such as affiliations emerging from neighborhoods, voting districts, or off-grid mesh networks.

The privilege to occupy multiple spaces of citizenship independent from the delineations of a formal boundaries comes with the responsibility to recognize the ongoing conflicts and endemic biases at the root of architecture and citizenship. These are old fights, ones that cannot be contained by any one administration or set of governmental figures. They ongoing and pitched against systemic conditions and policies of inclusion/exclusion that are almost infrastructural in scope.

The paradox inherent to architecture and citizenship, then, shouldn’t suggest a soft or relaxed position—it is tactical and a queering of outdated assumptions. In the face of rising populism and nationalism, hardening of physical borders, and enactment of restrictive migration policy in the US (and abroad), it is necessary to point and begin to speculate upon the ways that architectures, infrastructures, and urban policies might act in what Keller Easterling calls “productive piracy.”

Instead of being stymied by the traditional limitations of the architectural discipline, by the practice’s frequent complicity with power and capital, Dimensions of Citizenship asks architecture to look at how citizenship can teach us about the built environment—and vice versa—through a series of telescoping scales: Citizen, Civitas, Region, Nation, Globe, Network, and Cosmos. It pursues spaces, vocabularies, and methodologies traditionally outside the professional or disciplinary perview, asking who is uncounted by the census; what territories are unaccounted for by maps; which places do the shapes and colors of our bodies allow us to enter or from which are we denied entry; what is an architecture of survival after a history of fugitivity? These questions expose the loopholes, glitches, and other ways in, around, and under the lines that divide and suggest how architecture might begin to produce new forms of belonging outside of outdated strictures.

Unlike the fixity of a border wall, this type of expression is unstable and transitory, but not without the kinds of cautious optimism expressed in Jack Halberstam’s introduction to The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. Halberstam writes, “It ends with love, exchange, fellowship. It ends as it begins, in motion, in between various modes of being and belonging, and on the way to new economies of giving, taking, being with and for and it ends with a ride in a Buick Skylark on the way to another place altogether.”

The explorations expressed in Dimensions of Citizenship suggest possible assertions of architecture’s renewed agency in the political sphere while uncovering new actors and territories for design. The breadth of citizen-related characters, institutions, and spaces includes those that ask us to consider non-anthropomorphic views of the world, such as those of non-human actors like animals, rocks, or ecosystems. They also implicate figures (transnational corporations, governments, entrepreneurs with an eye on Mars)‚ that in exploiting opportunities for global/cosmic expansion or resource extraction, compromise the rights of individuals, indigenous peoples, and landscapes due to racial bias, greed, or willed ignorance.

Architecture, urbanism, and the built environment form a crucial lens through which we can better understand what we perhaps already know: that more than a legal status, citizenship ultimately evokes the many different ways that people come together—or are kept apart—through geography, economy, or identity. If citizenship itself designates both a border and the networks that traverse and ultimately elude them, then what kind of architecture might be offered offer in lieu of “The Wall”? What designed objects, buildings, or spaces might speak to the heart of what and how it means to belong today?

Dimensions of Citizenship is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the United States Pavilion of the 16th International Architecture Exhibition at La Biennale di Venezia.

Category

Subject

Dimensions of Citizenship is a collaboration between the United States Pavilion at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale and e-flux Architecture.

.jpg,1600)

.png,1600)