There was nothing but land: not a country at all, but the material out of which countries were made.

—Willa Cather, My Antonia (1917)

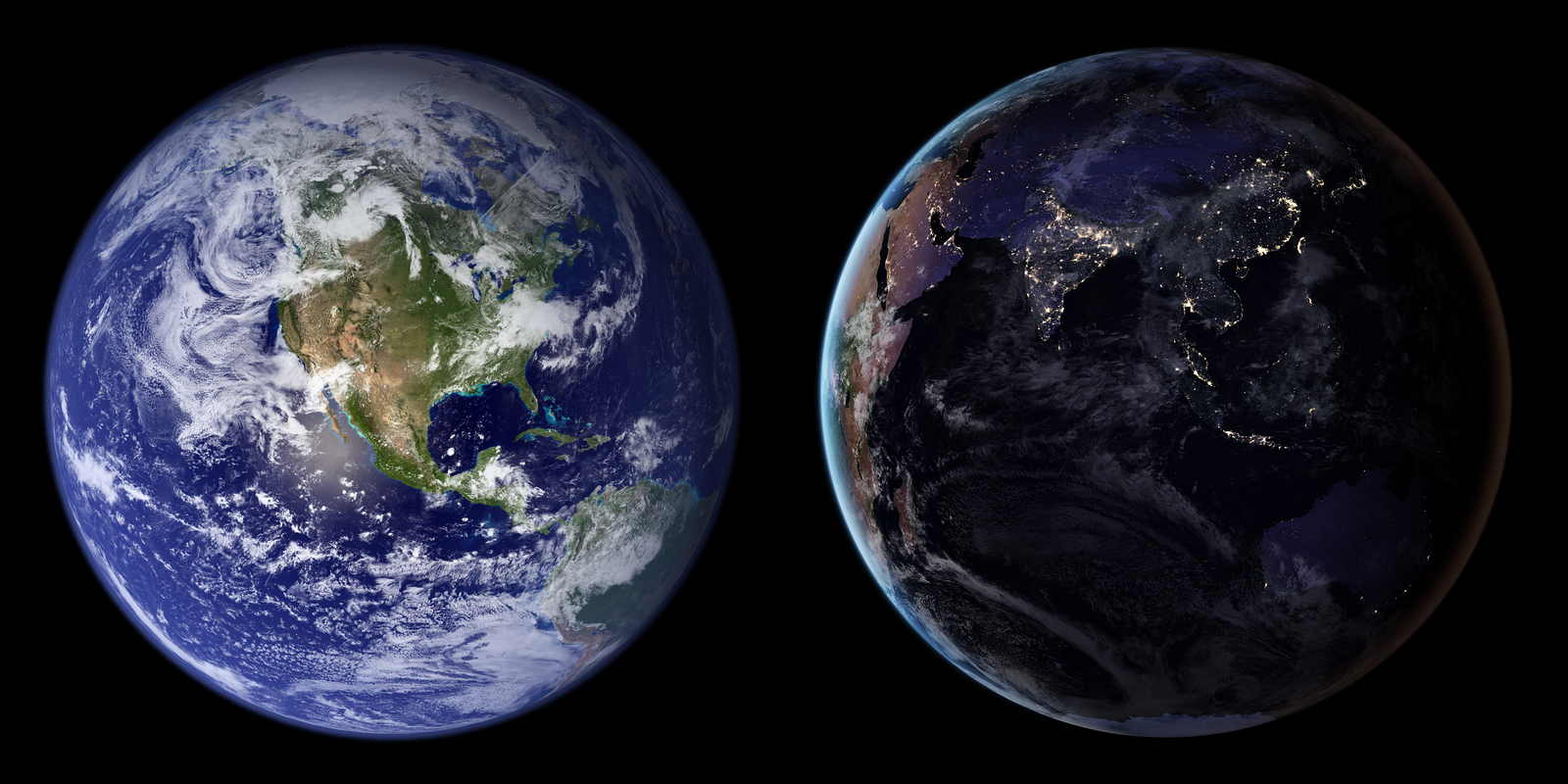

In the United States, land precedes the nation. Of course, historically speaking, all nations were defined in relation to a given territory, but land in America isn’t simply a territory. Rather, it is a civilizing entity through which citizenship is continuously negotiated. For centuries, the formation of Americans was described as the result of encounters with vast expanses of, rich deposits within, or the price per square mile for land. From carrying the word back east on gold found in the Sacramento River basin to the portrayals of farming paradise in railroad brochures, the cons of speculators or the architect’s imagination of a uniquely American way of building, the role of land’s description was paramount.

Land was thus transformed into a country through words. Different genres of writing—surveyors’ logs, personal diaries, public speeches, modern literature experiments, and gonzo-style architectural theory—have employed description in a variety of ways to shape an understanding of and meaning to American citizenship. While these modes first appeared in distinct historical periods, they are still present today, not only in the public sphere and literary circles, but also in architectural discourse. Throughout, land has been assigned different cultural roles far beyond its everyday functions, yet three stand out for their lasting presence throughout centuries of American development: liberation, speculation and history.

Liberation

One of the foundational myths of the United States is that the sheer quantity of land could spark a degree of freedom otherwise unheard of in the Old World. The association between the cultivation of land and the emergence of a new civilization became a prominent theme during the eighteenth century in the form of an agrarian myth. “He has become an American,” writes J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur in his widely popular Letters from an American Farmer of 1782, “by being received in the broad lap of our great alma mater.” Elsewhere, he argues that the land shapes civic virtue: “the instant I enter on my own land, the bright idea of property, of exclusive right, of independence exalt my mind.”1 Thomas Jefferson famously shared this sentiment when he wrote that “cultivators of the earth are the most valuable citizens. They are the most vigorous, the most independent, the most virtuous, & they are tied to their country & wedded to it’s liberty & interests by the most lasting bands.”2

These descriptions implicitly link cultivation, culture, and civilization, echoing the three terms’ shared origin in the Roman cultus, which was used in works such as Cicero’s De Republica or Virgil’s Georgics and which Jefferson likely knew well.3 In each, interaction with the land liberates one from the oppression of class structure and allows a republic of free people to arise. Yet even in eighteenth century America, Jefferson’s agrarian wonderland was mostly an illusion, inaccessible to large parts of society, deadly to others, and soon to be taken over by realtors and speculators. As American democracy matured, it became clear that farmers would be joined by workers and industrialists to build the nation. While reconciling the tensions between republic and democracy was a process that slowly unfolded throughout most of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, land maintained its capacity reject all forms of old world maladies. It was as if, as Alexis de Tocqueville observed, “the soil of America was entirely opposed to territorial aristocracy.” The result of this inherent opposition was a democratic nation with “simply the class of the rich and that of the poor.”4 The liberating and democraticizing potential of the land became a popular myth of its own, reflected in both patriotic hymns, “swearing allegiance to the land that’s free,” and individualistic folk lyrics, maintaining that “this land was made for you and me.”5

As working the land was no longer the essential task of all citizens, working with the land became synonymous with reinforcing American democratic principles. When Frank Lloyd Wright, for instance, advocated that all buildings should be “of the land,” manifest in “architectural features of true democratic ground-freedom [that] would rise naturally from topography,” or when the LSD soaked founders of Drop City declared that the land will be “forever free and open to all people,” they were reaffirming, each through his own set of values, the links between land and liberty, thus bringing its mythic narrative into the heart of postwar America.6

Curiously, even when land became an oppressor, land didn’t stop omitting an aura of liberty and promise. “[My parents] erred,” writes Ben Metcalf, “in their shared assumption, with so much of America, that ownership of the land was a natural right handed down from heaven, as opposed to a shameful ruse perpetuated by the banks… we were led to believe we had acquired the land, when in fact the land had acquired us; and whereas the land was, in my estimation, perfectly happy with this arrangement, in a remarkably short time we were not.”7

Speculation

While American leaders may have been musing on agriculture, it was always profit that led their way. The inherent gain to be found in vast expanses of land spawned a class of people whose task was to describe faraway places to potential buyers: speculators, boosters, and promoters whose words transformed the technical language of surveyors into frontier fantasy.

This practice was no stranger to the political elite. George Washington himself, a land surveyor by training, led the way. Having an eye for business, he became one of the most active land speculators in the country in the years before the American revolution. He was first involved with the Ohio Company which speculated on lands for the settlement of Virginians, and then partnered with neighbors to form their own Mississippi Company. In the 1760s, Washington developed his own schemes based on land granted to veterans, which he hoped to actively colonize while securing the best lands to himself. In 1770, he set on a “hunting trip” with the intention to describe lands around Fort Pitt, Pennsylvania and others nearby on the Ohio River. His descriptions of these lands, being “contrary to the property of all other lands I ever saw,” in which “the hills are the richest land; the soil of them being as black as coal and the growth walnut and cherry,” led to successful patents.8 In 1773, he advertised his 20,000 acres of acquired land to settlers, alluding that their value may increase dramatically if the plan to establish a new government on the Ohio “in the manner talked of” will materialize.

Boosterism, of course, was not always so elegant. As the westward race continued, it took an aggressive turn against the agrarian ideal. When describing the history of land in Southern California, Reyner Banham writes:

The Yankees stormed in on the crest of a wave of technological self-confidence and entrepreneurial abandon that left simple ranching little hope of survival. Land was acquired from the grant holders by every means in the rule book and some outside it, was subdivided, watered, put down to intensive cropping, and ultimately offered as residential plots in a landscape that must have appeared to anyone from east of the Rockies like an earthly Paradise.9

Paradise was often promised, and an entire history of financial bubbles—from the Yazoo land fraud in Georgia and Jay Cooke’s Banana Belt railroad lands to the countless boom cities in Kansas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, or California —followed. Throughout that history, richly illustrated promotional materials used architecture and urban design to color the often-exaggerated descriptions of instant cities in remote locations with a realistic tone.

Sarcastically referring to the hyper-optimism of such publications, one congressman from 1871 said:

I see it represented on this map, that Duluth is situated exactly half-way between the latitudes of Paris and Venice, so the gentlemen who inhaled the exhilarating airs of one, or based in the golden sunlight of the other, may see at a glance the Duluth must be a place of untold delights, a terrestrial paradise, fanned by the balmy zephyrs of an eternal spring, clothed in the gorgeous sheen of ever-blooming flowers, and vocal with the silver melody of the choice songsters.10

Echoes of boosters’ pompous statements of the past still resonate with contemporary real estate developers, marketeers, and their architects, narrating tracts of land for sale as “the future of Florida,” or marketing a bunker compound in South Dakota as the “largest survival shelter community on earth.”11 Long after the frontier closed and the entire country was colonized, land is still being described by speculators as enabling an American way of living, thus luring new immigrants, returning GIs, or retiring baby boomers to join the ride. In the Levittowns and the planned communities of New Urbanism, backed by government loans and sub-prime debt, one is invited to reaffirm his belonging to an imaginary nation of like-minded individuals. In these fantasy enclaves, carefully set up against a hostile environment of immigration, economic crises, and disappearing jobs that proliferate in the media, one becomes an American by living up to the land’s speculative promise. What lies outside these enclaves is mere fiction.

History

Beyond the reach of both agriculture and development there was always another category of land. The existence of immeasurable surfaces that were either out of reach or too difficult to cultivate, thus making them hard to be speculated upon has always been, and continues to be a defining element of American culture. “In the United States,” wrote Gertrude Stein, “there is more space where nobody is than where anybody is. That is what makes America what it is.”12

The emptiness where nobody (or at least nobody like us) is has been romanticized in countless accounts by scholars and popular media alike, from the lingering Jacksonian myth of the frontier as the condition in which the American character was defined, to Leonardo DiCaprio’s portrayal of surviving fur-trader Hugh Glass in The Revenant. While it was removed from human habitation, it was still associated with the natural rights of every (white) American. As James Fenimore Cooper wrote: “The air, the water, and the ground are free gifts to man, and no one has the power to portion them out in parcels. Man must drink, breath, and walk—and therefore each has a right to his share of earth.”13 The emptiness formed such a powerful image of American culture that vast areas were allocated by states and the federal government for its preservation, and citizens flocked by the millions to experience it. Nevertheless, it remains most difficult to express with words, overwhelming narrators with its complexity, strangeness, and sheer size. Landscape historian John Stilgoe writes that that “spatial immensity beggars designation,” urging intellectuals and designers to find words to confront “the continent itself,” and thus challenge their own disciplinary and social boundaries.14

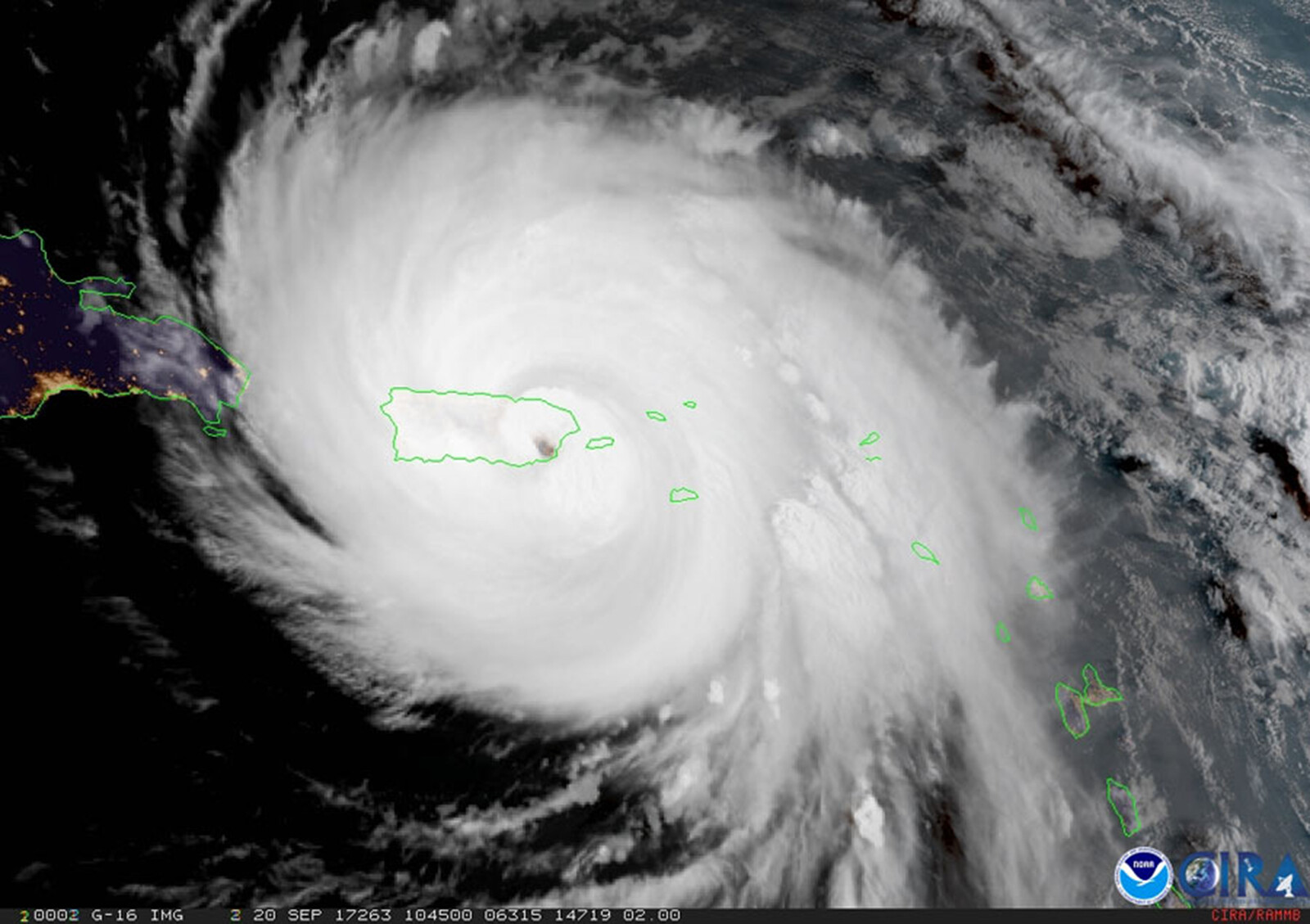

One such provocation was put forth by Aldo Leopold, based on years of attentive observations and detailed descriptions collected in his Sand County Almanac. Leopold’s concept of “land ethic” simply calls for enlarging “the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land.”15 Once the land is understood as part of a community of interdependent parts in which individuals compete or cooperate, the implications to notions of citizenship and natural rights become radical. For Leopold, the land ethic can become a lens through which the entirety of human history can be reconsidered: “Many historical events, hitherto explained solely in terms of human enterprise, were actually biotic interactions between people and land… The characteristics of the land determined the facts quite as potently as the characteristics of the men who lived on it.”16 In other words, the description of what was considered too difficult to describe—the complex systems that comprise the land and determine its interactions with humans—is a first step towards a more a new definition of an American way of life.

Future

In 2017, president Trump decided to roll back the decisions of his predecessors and cut down the size of two national monuments in Utah—Bears Ears National Monument and Grand Staircase-Escalanteby—by roughly two million acres. This decision was regarded by the liberal media as a dangerous precedent in which public lands will be made available to oil drilling and other extractive operations, thus betraying an American tradition of conservation. Yet Trump reasoned his decision by addressing the freedom of each citizen to take care of the land based on intimate first-hand acquaintance, rather than delegate it to professional bureaucratic sagacity: “Your timeless bond with the outdoors should not be replaced with the whims of regulators thousands and thousands of miles away. They don’t know your land, and truly, they don’t care for your land like you do.” In his view, a more direct democracy can emerge once the land will belong to the citizens who live on it. “I’ve come to Utah… to reverse federal overreach and restore the rights of this land to your citizens.”17 This perspective blends the understanding of land as liberation, speculation, and history almost seamlessly, moving back and forward in time to an imagined America. In this speech, as in other instances outlined above, description becomes more than a literary device, not only reflecting upon given realities of citizenship, as it is reflected in land allocation and manipulation, but actively pursuing the preservation or changing of such realities. In an era when words speak louder than action, how we choose to describe our environment and ourselves becomes even more crucial to the definition of a national identity, whatever the term may mean today. Then again, perhaps this was always the case in the United States.

J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur, Letters from an American farmer (London: Thomas Davies and Lockyer Davis, 1782).

Thomas Jefferson, Letter to John Jay, August 23, 1785.

Virgil’s ideal landscape and the pastoral ideal were of central importance to the American experience as it was outlined by both Europeans and Americans. See Leo Marx, The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (New York: George Dearborn & Co., Adlard and Saunders, 1838).

Irving Berlin, God Bless America (1938) and Woody Guthrie, This Land is Your Land (1939). Guthrie wrote his lyrics in critical response to Berlin’s song, emphasizing individual freedom: “Nobody living can ever stop me, / As I go walking that freedom highway; / Nobody living can ever make me turn back / This land was made for you and me.”

Frank Lloyd Wright, The Living City (New York: Horizon Press, 1958); John Curl, a Drop City founder, recalling the 1966 declaration in Curl, For All the People (Oakland: PM Press, 2012).

Ben Metcalf, Against the Country (New York: Random House, 2015).

George Washington, Journal of a tour to the Ohio River (1770), in The Writings of George Washington (Boston: Ferdinand Andrews, 1840).

Reynar Banham, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (Allen Lane, 1971).

Congressman J. Proctor Knott, a speech delivered in the U.S. House of Representatives (1871), quoted from A. M. Sakolski, The Great American Land Bubble (New York and London: Harper & Brothers, 1932), 305–6.

Quote from Howard H. Leach of Foley Timber and Land Company, as the company offered a 560,000 acres of land, roughly the size of the state of Rhode Island, for sale. See David Gelles, “560,000-Acre Swath of Florida Land Going on the Market,” New York Times, April 1, 2015. See also, Marketing materials for the Vivos xPoint project, ➝.

Gertrude Stein, The Geographical History of America (New York: Random House, 1936).

James Fenimore Cooper, The Prairie: A Tale (Paris: Hector Bossange, 1827).

John Stilgoe, “Wuthering Immensity,” Manifest – Journal of American Architecture and Urbanism 1 (2014): 12–19.

Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1949).

Ibid., 216.

Donald Trump, Remarks on the Antiquities Act at the Utah Capitol, December 4, 2017.

Dimensions of Citizenship is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the United States Pavilion of the 16th International Architecture Exhibition at La Biennale di Venezia.

Category

Subject

Dimensions of Citizenship is a collaboration between the United States Pavilion at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale and e-flux Architecture.

.jpg,1600)

.png,1600)