Nick Axel You have a background in healthcare, and in particular, in designing joints for prosthetic limbs. But you’re now heading the Directorate of Science, Technology and Innovation as Chief Innovation Officer for the Government of Sierra Leone. Can you speak about the relationship between these two things? Is technology like a social prosthetic waiting to be fit?

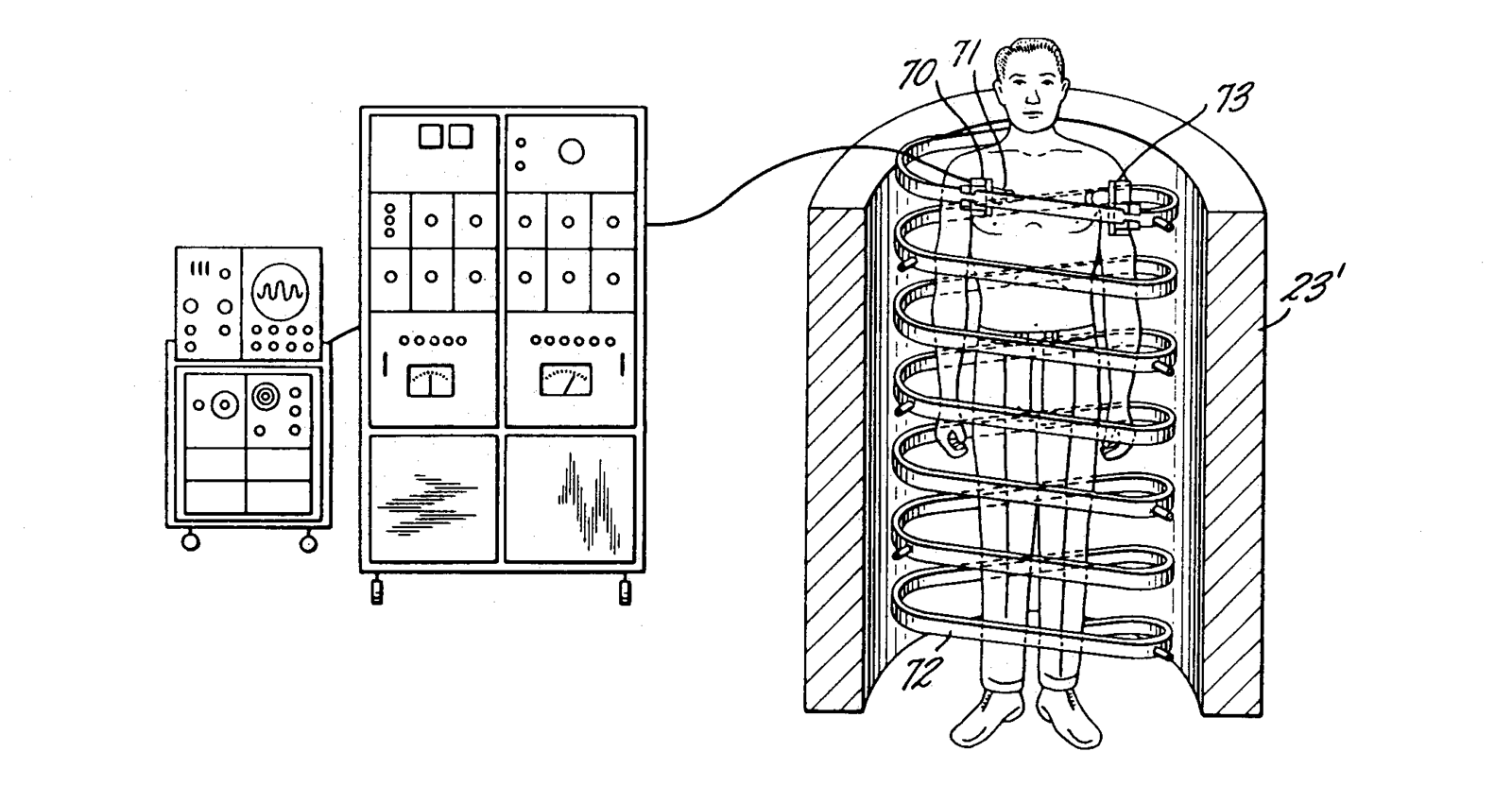

David Moinina Sengeh I’ve never thought about the idea of a social prosthesis… A prosthesis fills in a missing biological part, whereas with an orthosis, the biological part is there, you’re just enhancing it, adding to its function. I don’t know whether what I do in my role in Government is prosthetic or orthotic, but my interest in health and technology has always been there. When I was a kid, I went to clinics and shadowed my uncle in hospitals. I asked questions about the tools that were being used, why lights in the theater weren’t functioning in the way they should, why we couldn’t do surgery on a patient because the right imaging technology wasn’t available…

NA How did this lead you to where you are today?

DMS When I went to academia, I chose to study prosthesis and prosthetic interfaces because it combined the human body and soft tissue modeling with new materials and new manufacturing methods to solve a social problem. It was universal in application and was about pursuing knowledge and doing something that other people haven’t done before. That links with what we have been doing in government. This is the first time in the history of Sierra Leone, and I think in many other countries, that there is a Chief Innovation Officer. After many conversations with President Julius Maada Bio, our goal was to bring together science, technology, and innovation to address national development priorities that cut across sectors and industries. The hypothesis is that we can create an innovation ecosystem in Sierra Leone in which people are solving problems and addressing governance issues using technology.

NA You went into the field of prosthetics but you didn’t actually look at the object itself. For you, it was not about designing a better limb, it was about creating a better socket. So with regards to the Innovation Office you now head, maybe it’s not just about the data itself, but about thinking about the way that it interfaces with the daily lives of people?

DMS Developing new interfaces between the human body and prosthetics is driven by enhancing human comfort levels. It is driven primarily by an understanding of the way in which materials interface with our body and the impact it has on our soft tissues and internal systems. That is the main issue because how you measure the success of a prosthetic is whether patients use it, which often has to do with whether they get sores from using it or not. That is ultimately the same for my work now with governance. We don’t just want to deploy technology in government for technology’s sake. It has to have a change in people’s lives. They have to see the impact.

NA How have you begun to apply these techniques and technologies?

DMS Our pilot project was a study of the public education system in Sierra Leone, in which we collected data and analyzed relationships between the school’s facilities and the performance of its students. We found that there were key indicators of success, such as whether the schools had latrines and school gardens. If we were to go ourselves and look at a school and ask why its students aren’t performing well, those might not have been the first answer we would come to, but that’s what the data allowed us to see.

NA How did you go about coming across this as a solution?

DMS When we went into the data set for public schools, which includes, among many other things their facilities and learning outcomes measured by public exams, we didn’t know the answer. We probed the data with hypotheses; we developed research questions that allowed experts to explore the data. And what we’ve seen is that if you do unsupervised clustering and machine learning analysis on the data, you’ll be presented with things that you never would have thought about otherwise. If you’re an expert in school feeding, for instance, you will of course see in the data that school feeding has a big impact on learning outcomes. Which it does, but is school feeding the most efficient intervention that can be made to improve learning outcomes? What our analysis has shown is that we can discover important features that predict learning outcomes from our machine learning models. It’s not the final answer; it’s a model that needs to be probed and tuned. But it allows us to have conversations in much more structured ways.

NA Do you get to define the categories of data that are collected?

DMS No, we’ve been working with pre-existing government data, which was set up by experts who decided on the hundreds of data features to be collected.

NA That shapes the terrain for intervention though, no? You can compare latrines with food services and see which one actually had a stronger impact on learning outcomes, but not, for instance, sunlight or air ventilation, unless that’s been specified in the dataset categories.

DMS Sure.

NA Beyond this pilot project, what are some other spaces that you might start to work in? Or, said differently, what are some other datasets that you think can be used to change Sierra Leone’s cities?

DMS I think there are lots of opportunities to apply advanced analytics for developing and providing solutions for cities. Cities are ultimately networks, so it’s a network problem, which means that it’s a machine learning problem. Cities are networks of infrastructures: houses are nodes with links between; schools and hospitals are different kinds of nodes, with links between… Road accessibility is a feature of the link. You can use all different types of data—like demographics, accessibility, and social facilities—on an integrated GIS platform to help determine where is the optimal place for the next piece of infrastructure to be built. If a city has a limited amount of money, it has to decide what roads to build, what schools to build, which hospitals to build or renovate. How is that decided? Where is it placed? Models can identify hotspots that point us to places that might not have been apparent otherwise. It doesn’t give you the one and final answer, but it allows you to have more directed conversations with people about where infrastructure should be built.

NA One of two key questions to address for the future of this program seems to be the expansion of your data sets; the acquisition of more data and more detailed data about the city. The other is the generation of expertise within the country and within the state. You know how to work with these systems, so you’re able to pioneer this program, but in the end, it’s also about generating an base of knowledge throughout the population.

DMS It’s important that we develop the capacity for the country’s young people to do state-of-the-art analytics and that this expertise comes from Sierra Leone itself. Otherwise it’s never going to be the people’s answers. We don’t have a data science program in Sierra Leone now, but we are engaging with academic institutions both at home and abroad to create that infrastructure. We have to think about how we cultivate the pursuit of knowledge and build the systems that go beyond where we are today. The government can’t analyze all the data, and we don’t want to. We want to show what is possible.

NA Are there any plans to integrate data science into the curriculum for public schools?

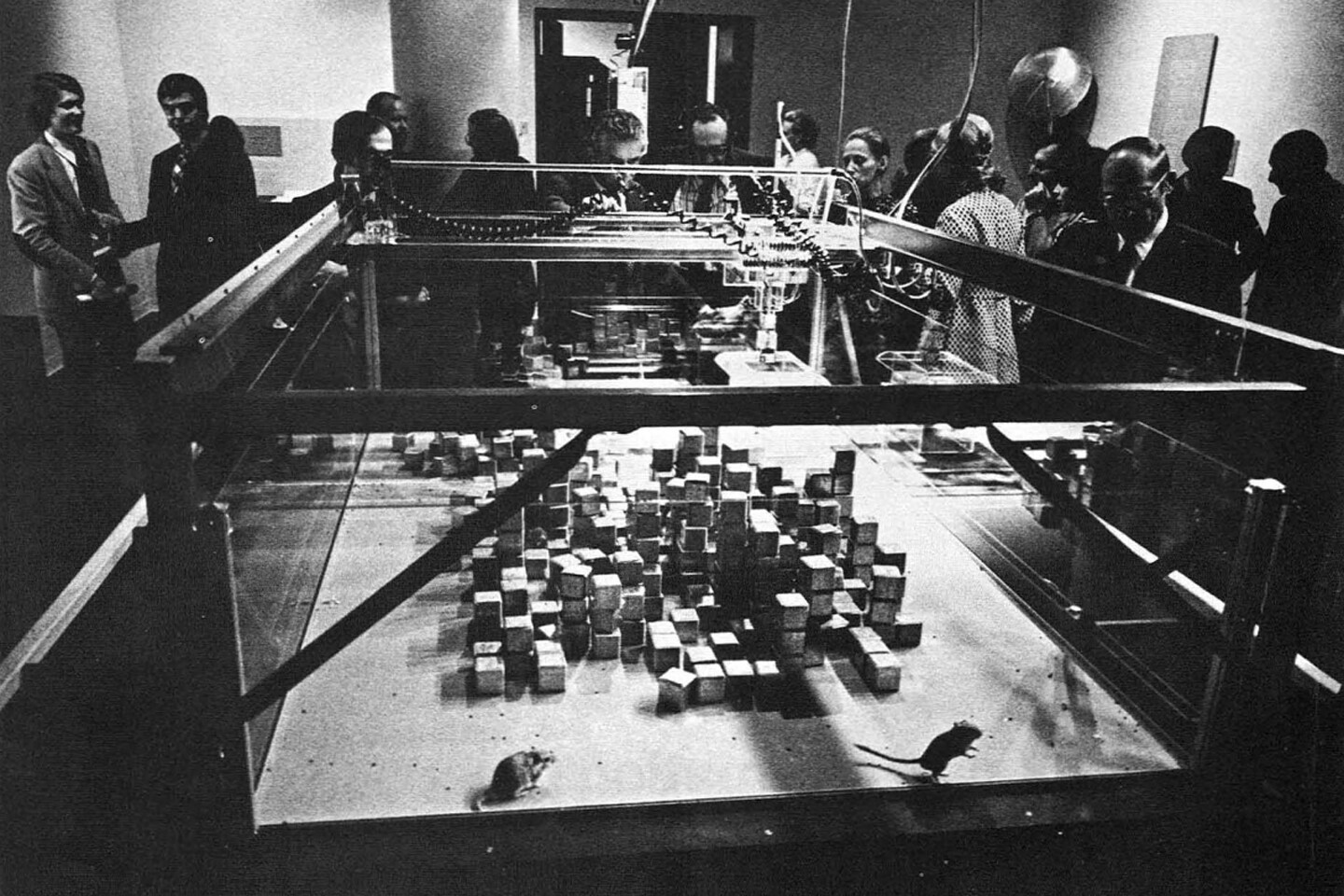

DMS The opportunities are enormous, but so are the challenges. Public education is a conventional institution, which by definition doesn’t easily change. Everybody should learn how to code. It should almost be a requirement, like learning how to read and write. Kids actually already have computational thinking. By building and playing with blocks, computational thinking is learned and developed. The problem is that we have systems in place that stop children from thinking computationally.

NA Or the lack of other spaces for those ways of thinking to continue and develop.

DMS Most certainly. And it’s not really just about what we can do as a Directorate, or as the Office of the President, or as the government. It’s how everybody gets to think about an opportunity to reimagine and propose new ways of thinking. So if there are architects who have crazy and interesting design solutions about popup labs and for spaces that allow for collaboration, engagement and learning, and very small ways that can expand, I’d love to see it. Ultimately, there are limits on how much we can do, but that doesn’t mean we have a limit on how we can think.

Digital × is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Norman Foster Foundation within the context of its 2019 educational program.