Nick Axel You founded the Architecture Machine Group (AMG) with Leon Grossier in 1967 at MIT to investigate and speculate upon the emerging relationship between computation and architecture. It started with the urgency of creating flexible, reconfigurable, personalized architectural systems, and designed the interface with which to interact with and redesign it. You took housing as the site to experiment with new systems and interfaces for participation, and perhaps even vice versa. This was over fifty years ago, but how do you see these questions of participation, of flexibility with regards to the built environment today?

Nicholas Negroponte I did not continue working with those specific concepts very much thereafter. Flexibility and participatory architecture had become something that many people were pursuing at the time. I was influenced by Yona Friedman, who had a particular way of going from a graph to a floor plan. We saw his ideas of flexible space as a great way to experiment with and develop what we were trying to do: make computers easier to use. Participatory architecture occupied our attention for a couple of years, but ultimately did not capture our long-term attention. Ease of use did.

NA This idea of flexibility and participation is very often just an idea. That was made very clear by the way your work progressed after the AMG and with the MIT Media Lab: that it’s not just about the idea, but about actually being able to do it. You are famous for championing the phrase “demo or die.”

NN Somebody else actually coined the term “demo or die” and I am not sure who. It might’ve been Muriel Cooper, because I arrived one day at her lab and saw it written on a wall clock where all the numbers had been taken out and were replaced with the letters, “demo or die.” I thought it was pretty good.

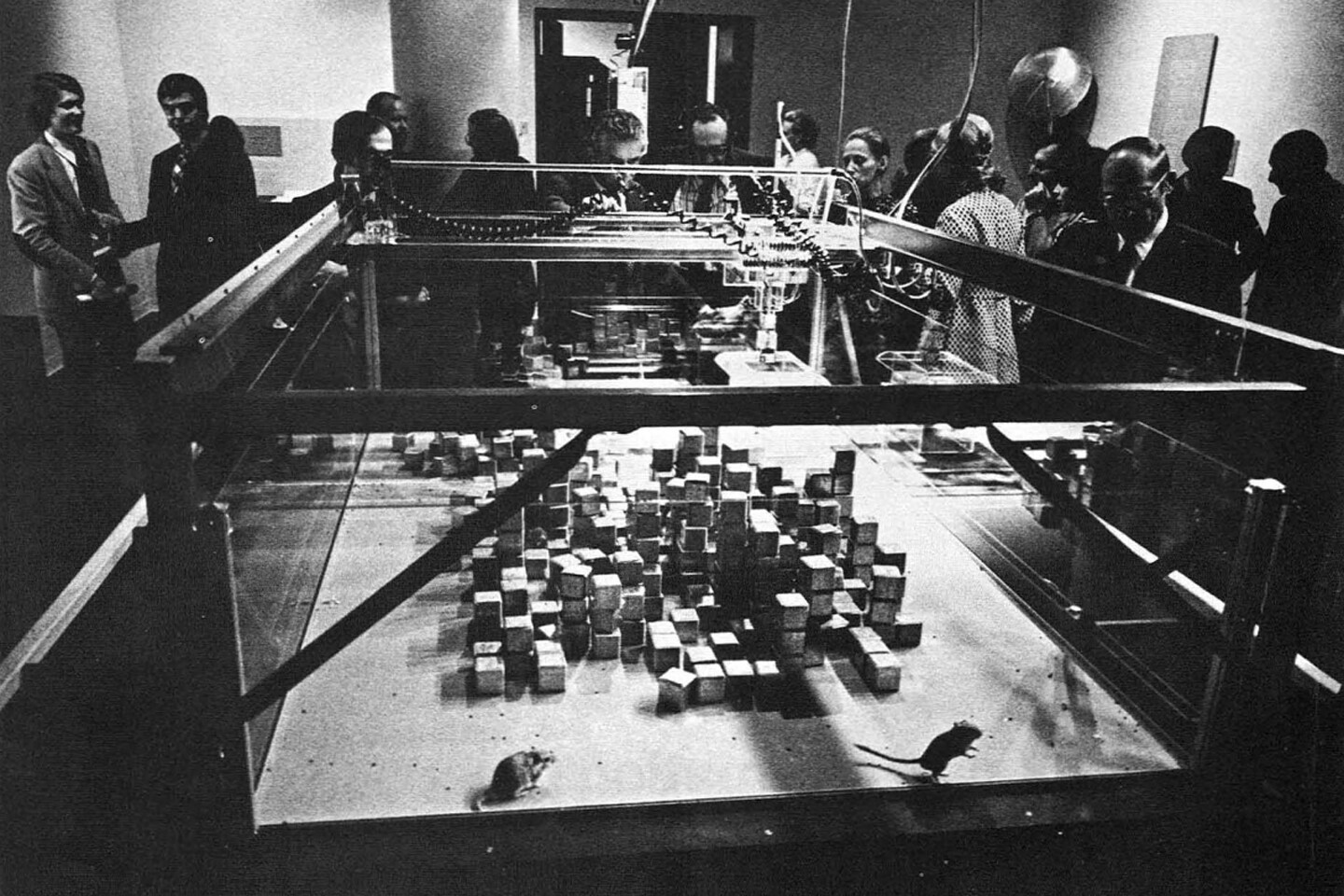

NA Your early URBAN experiments into human-computer interaction are exemplary in this regard. In particular, your URBAN 5: SEEK experiment, which was exhibited at the Jewish Museum’s Software exhibition in 1970, can perhaps be seen as a precursor to the contemporary ethos of tech innovation to “move fast and break things.” According to one description of the project, it “featured a Plexiglas pen filled with four hundred silvered wooden blocks, a robotic arm that tried to stack and order the blocks, and a horde of gerbils that inhabited the pen. The gerbils made chaos out of the blocks and SEEK tried to keep track of them.” But the “deeply personal dialogue” you envisioned that would emerge from the animal-computer interaction failed, and instead, SEEK “tended to kill the gerbils.”1

NN I just saw The Architecture Machine, my book from 1973, for the first time in a very long while. I really don’t see or hear people speaking about these topics very often.

NA I feel like the history of the early entanglement between computer science and architecture is just now being written, and practitioners such as yourself and Christopher Alexander are at its core.2 It’s part of the process of waking up from the distracting allure of new technologies and the image of the new. Historians and practitioners, not just from architecture but from all sorts of fields, are starting look back and search for the origins of the digital present, because we can see the same questions that we are facing today arising and being dealt with back then. So on the one hand, it provides a sense of historical continuity, to calm the nerves that the present tries to shock. But on the other, maybe it’s all done with the hope that if we understand the conditions which first brought the questions about, we can find answers to them that are more effective than the one’s we have today. Like those ideas that you started with, of participation and flexibility. Back then it was so often tied to the idea of democratization, but since then it’s become commodified as “personalization” and “customization,” and in a way that privileges convenience and ease at the expense of accessibility and knowledge. Much of your work, from the AMG to One Laptop per Child, seems to use technology as a tool for democratization, while at the same time democratizing technology.

NN “Democratize” is a funny word. A synonym for it is “vulgarize.” But if you look up the meaning of vulgar, it’s actually a rather good word. Albeit a bit dated as a definition, something vulgar is “characteristic of or belonging to the masses.”3 In some sense it means to popularize, or to make something common. My work has always been less about democracy and more about making common.

NA So in that sense, distributing rights, distributing agency?

NN It’s a little bit like how clean air is not necessarily trying to democratize air; it’s trying to make it clean for everybody.

NA In some of your early experiments, you were looking at the potential of incorporating sensors into architecture. This can now be seen within the genealogy of the multi-billion-dollar industry of the Internet of Things. How do you feel about the way this economy, this industry has developed, and how do you think it might change architecture and the relationship we have with the built environment in the future?

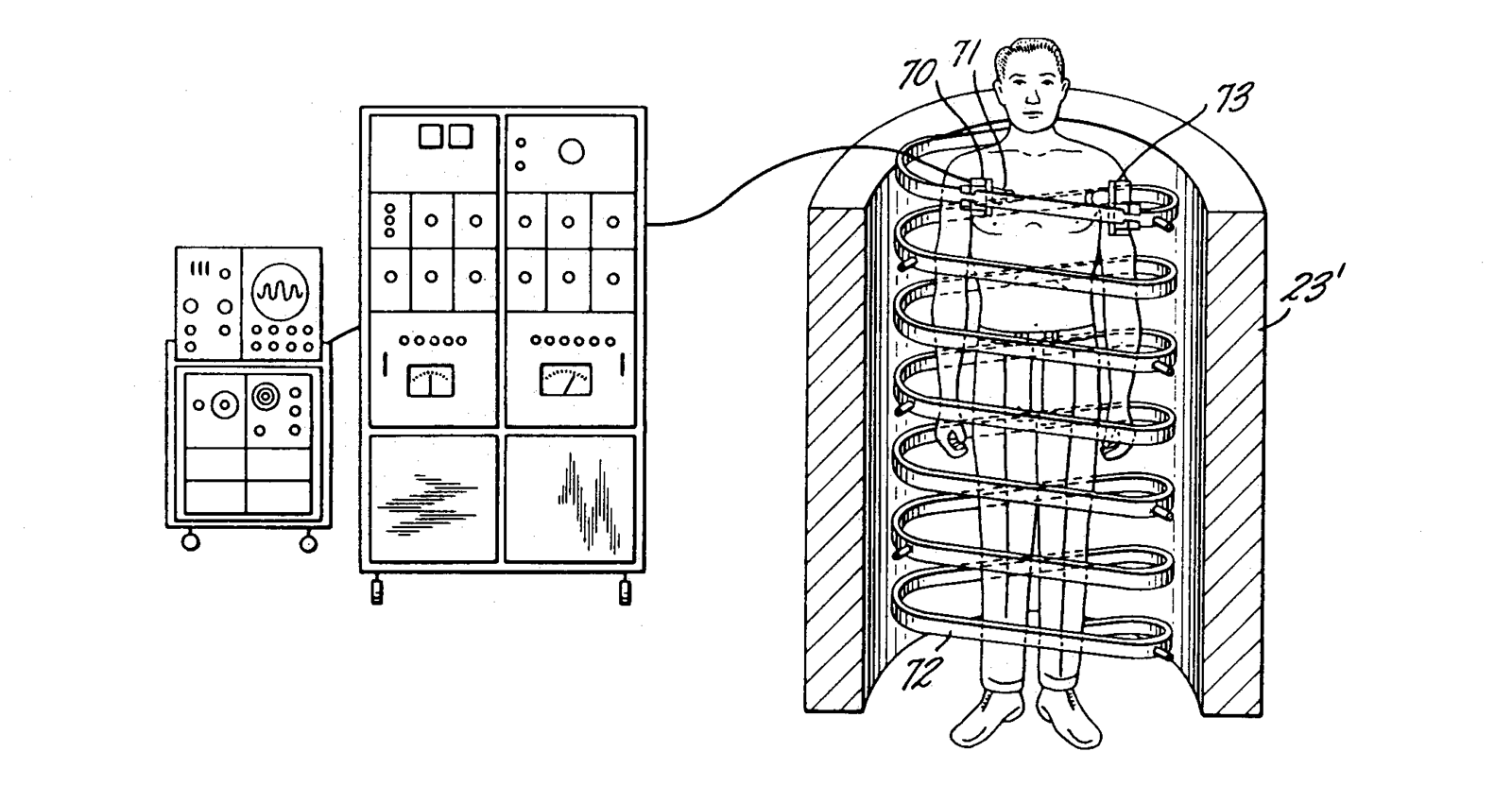

NN The question of bringing sensors and computational intelligence into architecture was never just been about a change in computing speed, but also, and perhaps even more importantly, a change in the physical size of devices. Back around 1970, when I started working with the idea of ambient computing, technology was starting to get small enough that it was possible to imagine a future where they would almost disappear. That was the trajectory they were on. And once that starts to happen, the line between what is and is not a computer disappears. That was a long time ago. Today, the boundary between the device and the environment in which it lives— which could be my body, clothing, or a building—is also beginning to disappear.

NA Technology is becoming smaller, faster, and cheaper, but that’s not what makes them “smart.”

NN Once you start inventing things that can talk to each other, you have to build a nervous system. One major tipping point for this was with the launch of the first GPS satellite in the early 1970s. GPS was so important because suddenly, anything could know where it was. That was never true before. Maybe something could know it was next to something else, but it couldn’t know where it was in the world, and it certainly couldn’t tell which way it was pointed. GPS pushed the idea of embedding computation in things, because, in a funny way, they started to know more about themselves.

NA But it seems like it’s really only starting to take off now, that computation is finding its way into “dumb” things and making them “smart.”

NN Forty years ago, when I gave talks about this, people would be confused. They wouldn’t understand why we would want things to be to be connected. So I’d give examples, like a Coke machine that’s able to say when it’s empty, or more sophisticated ideas like a thermostat reporting when it’s freezing, so that somebody can know to do something before the pipes burst. The logic behind it became self-evident very quickly, but people didn’t think it would become so granular and be everywhere. Now that’s become possible, but the so-called Internet of Things really talks about the performance of a thing, and not all of those things collaborating and performing together. Another example I would use decades ago was a doorknob that would recognize you and open the door. To make sure that it only opens for you, there would need to be a vision system, and lots of other computational parts in addition to the doorknob that work together in collaboratively figuring out you are you. And it doesn’t have to go back to a central black-box server to find your picture.

NA Yet it seems that the collection of this data, that uploading of a picture to a central server, is one of the prime drivers of the development of internet of things devices. What then, in your opinion, are some of the values or principles that should drive innovation today?

NN Let’s disentangle the word “innovation” from the projected market share increase from perceived novelty and so-called functionality. I was on the board of directors of Motorola for fifteen years, where we had to decide what the next product was going do that the previous one didn’t. There was this constant search for something, and then once you’d think you found it, you would keep it a secret until it gets released, and then somebody writes a positive story about it, or not, and you would have hit a home run, or not. It’s interesting to see what people dismissed in the beginning compared to what people use today. When cell phones were “invented,” early phone operators didn’t want data. They said people won’t use it; we were told all people want was voice. It was only when a few of us told the phone companies that they can communicate with their customer over SMS that they said it might be a good idea. That’s how texts got into the system.

NA They’re also messages that you can’t really ignore.

NN Yes. But nobody pointed out that if you can send them, your subscribers, a notice, they can send you back one. In other words, the service had a new mode of communication built in. But back then, people would still laugh if you would say that people will barely talk on the phone, but mainly message. But today, that’s what happens. Most people prefer to text. I have largely stopped using voice, and make less than one voice call per week.

NA Our behavior is quite easy to change, as we’ve seen over the past thirty years, particularly with regards to our relations with these devices. But our cities operate at a slower speed. How do you perceive these different temporalities of change?

NN One of the most dramatic changes in the recent past is that when I left university, everybody was exiting cities, but now everybody wants to live in them. Back then, they were unsafe, they weren’t clean, they didn’t have particularly good education. There were all sorts of reasons. And this mass migration out of the city left industry, business, and pretty serious poverty behind. These were actually the conditions that the early work of AMG was responding to in its push for flexibility and participation. But today, no millennial wants to live in the suburbs. Even most of the people who left the cities for the suburbs back then want to go back. This is particularly true for “empty-nesters” in the USA. People want to be in the city for its vibrancy, for its culture and diversity. Cities don’t go to sleep at eight or ten at night, which a business center might. It has a life. That has been a profound change to our cities, and it has happened just as fast as the changes that have been happening to our bodies and our habits. But not unlike the changes that are happening to our bodies, these changes to our cities come with their consequences. Because so many people are moving into cities, the cost of living in them has risen. Only the rich or young can afford it, albeit in different ways.

NA Young people often feel like they need to live in cities, and because they can’t afford to live on their own, they have to share housing with two, three, four, or sometimes even more people. Standards of living go down.

NN Well, for a twenty-year-old, maybe sharing is itself a quality. Maybe millennials moving into cities today don’t value privacy as much as previous generations, and think that having multiple roommates is more fun. I don’t want to judge whether it’s a higher or lower standard of living, but I don’t think it’s per se lower. Also, it’s important to note that contemporary housing is designed differently. Shared spaces, like barbeque areas, work spaces, and exercise facilities have become apartments’ common areas of today.

NA Do you see this this departure from the city that took place in the twentieth century as a historical blip, or do you see this kind of countryside-city migration as a cyclical pattern?

NN It’s hard to claim something to be cyclical when it’s only cycled once. It’s possible to understand why people moved out to the suburbs when they did, and especially in the United States, where public schools are funded by local real estate taxes, which is really a dumb and damaging idea. It’s also completely possible to understand why one would want to move back into the city. But what I have a harder time understanding today is why a person in the developing world with a beautiful life in a village wants to go into a city and live in a slum. I know why, but to “understand” something and to ask “why” is slightly different. There was a false promise that in cities, you would find jobs, educational opportunities, culture, all these things. But that really hasn’t worked out. The worst form of poverty isn’t the primitiveness of a village: it’s urban poverty, the slum.

NA In relationship to these questions of migration, what do you think are some of the most pressing and urgent issues facing the future of cities today?

NN I can think of many, but if I had to say which might be at the top, I’d have to look at the values to which people aspire in cities today, which is different from back when I was growing up. If you could get rid of roads and cars, and find other ways to do what they do, you would change everything. The impact of shared driverless cars on cities would be enormous, beyond most people’s imagination.

NA It would certainly allow space to be used more efficiently!

NN Well, if you want to call that efficient. Efficiency is a funny word because it’s not like the spaces that might be freed up by driverless vehicles will necessarily be replaced by parks or housing.

NA Not so stupidly, then?

NN Not so car-centric.

Molly Wright Steenson, “Architecture Machine Group: Artificial Intelligence Meets Architecture,” in The Other Architect, ed. Giovanna Borasi (Canadian Centre for Architecture and Spector Books, 2015), 393.

See recent books such as: Molly Wright Steenson, Architectural Intelligence: How Designers and Architects Created the Digital Landscape (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017), and Andrew Goodhouse, ed., When is the digital in architecture? (Montréal and Berlin: Canadian Centre for Architecture and Sternberg Press, 2017.

“Vulgar,” Merriam Webster, ➝.

Digital × is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Norman Foster Foundation within the context of its 2019 educational program.