In the past decade, as new aesthetics of “artisanal” food production circulated in architectural and popular media, architects responded with a bevy of proposals for urban farms. Beautifully rendered, well-intentioned, and offering advantages over the intensive pesticide use and labor abuses of industrial farming, many urban farms drawn in architecture studios nonetheless tended to minimize the work of people who had long grown food in cities—especially, as Ashley Gripper and Kyle Powys Whyte have pointed out in the US context, Black and Indigenous people—by suggesting that designers were necessary to “restore” food production to urban areas.1 Much of this work tended to oversimplify food systems, imagining that urban residents could feed themselves on microgreens and strawberries alone instead of the grains and proteins that make up so much of our diets, and did not engage issues of labor and maintenance.2 While many have studied the logistics and politics of large-scale food systems, it remains difficult to talk through the reigning binary opposition of “small-scale vs. industrial”—a binary which reduces the complexity of food systems, perhaps in order to make them subject to design interventions.

As food policy scholars and activists make clear, the challenges of repairing broken food systems in this time of dire climate crisis necessitates cross-scalar strategies: nurturing food sovereignty within smaller communities as well as transforming farms, policies, working conditions, and distribution networks at the industrial scales on which so much of what we eat is made, and where impact on emissions is the greatest.3 There are many challenges to address: securing and maintaining affordable land for farming, remaking agricultural subsidies, shifting away from animal agriculture, tending to pesticide residue and soil regeneration, coping with the financialization of agricultural commodities and financialization’s impacts on debt, simplifying distribution, and urgently addressing the ongoing injustices of land dispossession. Architects can work on the small-scale or the large scale, or thread between them: these approaches need not be exclusive, nor opposed.

To participate in food systems transformation, architects and designers can learn from a growing body of policy research, as well as from food growers and workers who have on-the-ground expertise in food production and its challenges. However, even with the benefit of this learning, architects who are interested in “redesigning” food systems should recognize the limitations and potential harm of solutionist-style projects that parachute into this complex world. Architects who want to engage in food system transformation can be of great service as part of interdisciplinary teams. They can also work from within their disciplines by assisting in the project of representing visions of an ecologically and socially sound food system.4 This is important, because a representational project can be advanced with disciplinary knowledge architects largely already have.

Renderers of future of food systems can learn from architectural history. One brief but instructive moment occurred during the last major transformation of agriculture—from a small-scale to an industrialized system—as the French agricultural minister Georges Monnet and the architect Charlotte Perriand collaborated to represent the potential benefits of a growing system that did not yet exist in France. After a political alliance of left parties, the Front Populaire, captured the French legislature in May 1936, the new socialist prime minister Léon Blum appointed Georges Monnet as the Minister of Agriculture. A member of the French Section of the International Workers’ Party, or SFIO, Monnet was deeply committed to promoting the rights of agricultural workers. He was also the owner of a 250-hectare model farm, and an experienced cultivator.5

Monnet began his work with policy: his program of “re-valorization of produits de la terre” sought to raise the cultural and monetary value of food grown in France. He promoted the interests of small-scale farmers and extended a number of social benefits to agricultural workers, hoping to negotiate higher wages.6 Monnet was especially committed to regulating when and how grain could enter the marketplace in order to maintain prices for farmers even in times of surplus. Fixing the market and regulatory systems for agriculture would, in theory, ensure a proper balance between the requirements of urban consumers—who need affordable food—and rural producers—who need better and more consistent wages.

Monnet also understood that there was an aesthetic and architectural component of his program of rural renewal. In the early 1930s, he had worked with Le Corbusier, who he assisted with finding both a site for the Temps Nouveau pavilion and sponsors for the CIAM 5 meeting in Paris in 1937.7 But Le Corbusier’s land policies didn’t entirely align with his own. Monnet instead turned to the architect, photographer, and interior designer Charlotte Perriand, who worked both on her own and in Le Corbusier’s office, to help visualize and communicate the Ministry’s new policy goals. Perriand was an obvious choice for this role. Aligned politically with the Popular Front, her enormous photomontage of scenes of everyday life in impoverished neighborhoods in Paris, La grande misère de Paris (The Great Poverty of Paris) had been shown at the Salon of Decorative Arts in 1936 and demonstrated her ability to use out-of-scale photographic images to map social challenges in the city.8

Perriand was commissioned by Monnet to decorate a waiting and meeting room of the Ministry of Agriculture.9 A collage of text and images at transformed scales, her project followed a similar graphic style to La grande misère de Paris. Perriand juxtaposed blow-ups of soil with the faces of workers, their expressions filled with emotion. She enlarged images of plants and set them among the cultivators at dramatic angles, suggesting that ordinary plants, people, and land were the basic elements of agricultural transformation. The realist photographs, which borrowed from the visual language of the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement, were also surreal because of their shifted scales. Perriand glued the images directly onto the plaster of the walls so that they could not be easily removed by a future administration without destroying the walls themselves.10 Anyone who entered the Ministry would be confronted with these literally indelible images, ones that corresponded to a new, humanist, pro-technology aesthetic language that accompanied Monnet’s desire to support the cultures and people who cultivated food.

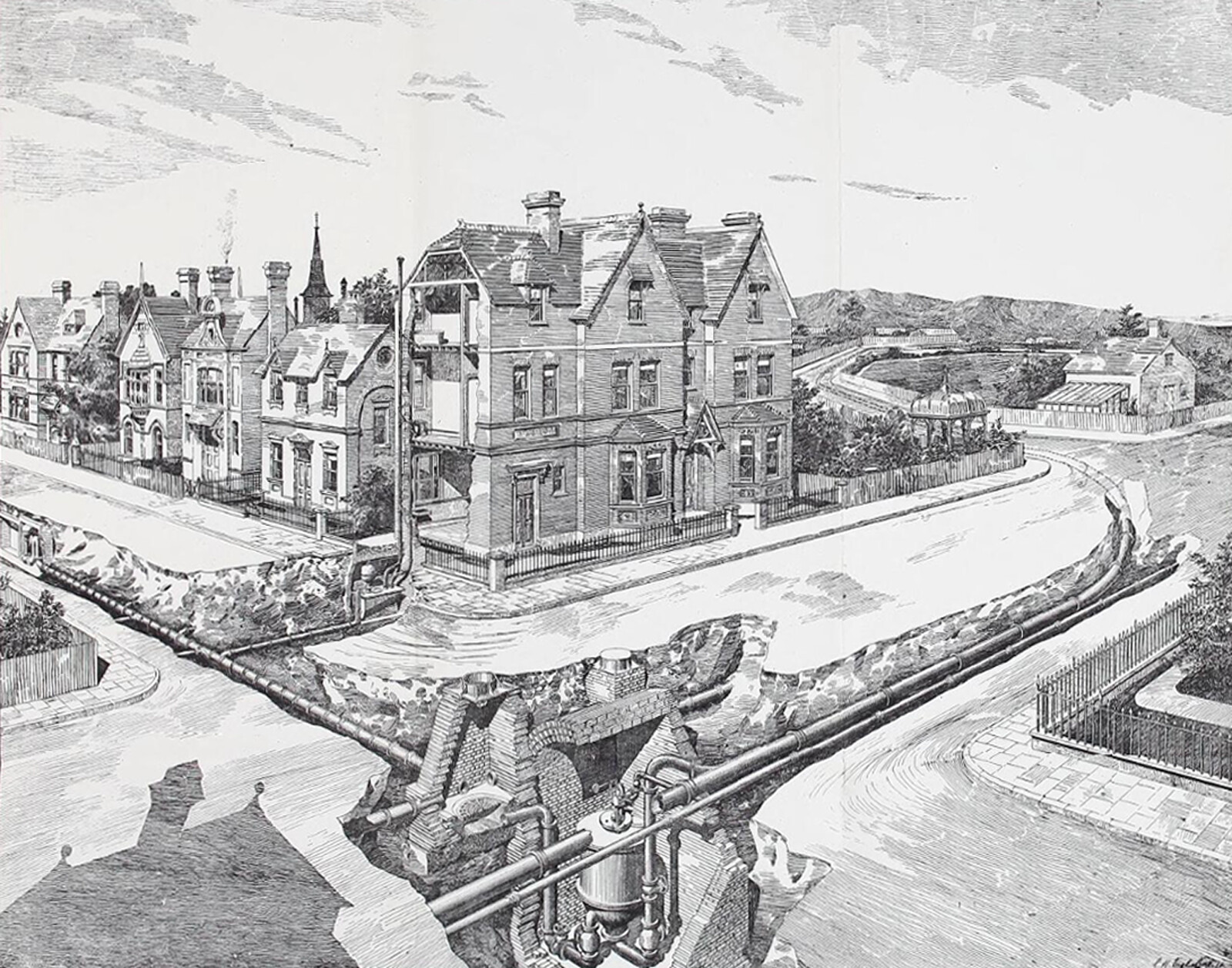

In order to gain support for Popular Front agricultural policies, rural transformations needed to be more visible to Parisians, who were often unaware of the source of their provisions and disconnected from the political economies of food production. As the 1937 World’s Fair approached, Monnet planned an agricultural pavilion that would illustrate the objectives of the Ministry. He hoped to use the exhibition pavilion to make clear the plight of rural workers, the potential of rural space, and the work his office intended to undertake to improve rural life. Monnet asked Perriand to cover the walls of the pavilion that was allotted to the ministry, which had been designed by the architects Henri Pacon and Andre Masson-Detourbet prior to the election of the Front Populaire.11 Perriand then asked Fernand Léger to collaborate with her on the murals. In simple graphic language, the photographs selected by Perriand were painted over by Léger and made the case that rural life included modern infrastructure. The collaged images show new power lines and the benefits of electrification, the iron structure of the Eiffel tower, and delicate flowers held in triumphant fists, representing how a modernized countryside could be a key part of a project for a renewed France. Popular Front proposals for the rural workforce were displayed along the interior of the pavilion: “collective bargaining,” “limits on the workday,” “retirement benefits for older workers,” “benefits for families,” and “paid holidays.”

Monnet understood that agricultural work supported the entire country, and with Perriand’s help, was able to depict what a modernized countryside—one with fair compensation for workers, and one which didn’t rely on democracy-busting syndicalism—could look like. Her work helped to clarify the aspirations of the Popular Front before they could be codified into policy; farmers were depicted as triumphant workers whose essential labor put them in solidarity with industrial workers. Local expertise and culture were represented in photographs, and seemingly would not be erased by mechanization of farming. Images of cooperation and connection between city and countryside made both the Ministry of Agriculture and its pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair into a vision of technologized and de-peripheralized rural space. Perriand wasn’t attempting to herself remake the food system, but instead to offer it an aesthetic language that could connect agricultural transformation to other Popular Front programs.

The Popular Front didn’t maintain power and the Second World War interrupted France’s shift towards farm modernization. Monnet’s vision of intensified farm production that would serve the needs of paysans was lost. After the war, architects who got involved with rural reform were enlisted as designers of rationalized farms that would replace those destroyed during the Second World War.12 These projects improved material working conditions for farmers, but not their economic power.13 The agricultural transformations that eventually occurred in France from the 1950s to the 1970s—including consolidating large-scale farms, intensively using pesticides, and producing surplus for export—changed rural standards of living, production practices, and distribution patterns, but were also detrimental to soils and watersheds. While they drew from Monnet’s ideals and Perriand’s modernist aesthetics (Monnet even was briefly given the post-retirement task of organizing a museum celebrating agricultural transformation during the early 1970s), they brought about challenges for small-scale farmers and ecological problems that impacted the entire country.

Even though they did not take hold as intended, Monnet’s valuing of farm workers’ lives and time, and Perriand’s practice of symbolizing and simplifying visions of agricultural futures could be still meaningfully revivified today. Renewed aesthetic and representational strategies could help designers trying to think beyond the troubled industrial model envision better labor conditions and ecologies in our food systems, and connect production to consumption not through the lens of “artisanal” nostalgia but through a language of justice and ecology.

Contemporary collaborations between designers, planners, and food systems experts offer many potential models for such futures. Landscape historian and architect Anita Bakshi and her students at Rutgers University collaborated with the Ramapough Lunaape Nation on an e-book, exhibition, and film (2019–2021) about Ringwood Mines, a Superfund site on Lunaape lands which left a legacy of cancer, illness, and toxic soil.14 Bakshi and her students collected and generated images of pasts and futures at the site, interviewing residents about how its toxic legacy has impacted them. As part of their work, students were in conversation with Chief Vincent Mann and Clan Mother Michaeline Picaro, who established the Munsee Three Sisters Medicinal Farm in 2019. This farm grows foods and medicines and maintains land in Sussex County, NJ as a practice of creating food sovereignty and community repair.15 As students documented demands for environmental justice, they helped to draw and represent visions of reparative farming futures. Their illustrations, diagrams, and maps were not readymade solutions, but instead are traces of a practice of community and conversation.

Plans developed from within growing communities offer other forms of representational and ecological promise. Soil Generation, a coalition of Black and Brown women and non-binary farmers in Philadelphia, draw from the insights of longtime urban farmers to guide recommendations for urban farm policy for the city and share knowledge about agroecological food production.16 As farmers with deep expertise in urban food production and community building, but also as a group threatened by land loss and gentrification-led displacement, Soil Generation promotes food sovereignty by working to preserve access to urban land for urban gardeners and farmers. Mapping and outlining land preservation and acquisition strategies for Black and Brown communities in particular, their work redresses the systemic racism that governs access to urban land. By writing plans as well as supporting small farmers, Soil Generation pushes beyond the binaries of artisanal-vs-systemic of the past decade, and instead towards a model of justice and repair in the design, planning, and maintenance of cultivated spaces.

In early twentieth century France, the new aesthetic language attached to the program of socialist agricultural policy helped communicate its benefits to people alienated from food production, offering a rapprochement between urban and rural spaces, and a vision of a world of cultivation that did not yet exist. Today, as we urgently attempt to adjust our food systems to cope with the climate crisis, it is important to center models of survivance and ecologically-sound food production that have long come in to being, as Soil Generation, the Ramapough Lunaape, and so many others have done. Architectural world-building can generate enthusiasm for policy, and architectural solidarity-building can support the repair of systemic injustices of land theft, speculation, and toxicity that have damaged so many food systems in the first place.

I have singled out these two thinkers for their focused critiques, but many others have made this point. See Ashley Gripper, “We Don’t Farm Because It’s Trendy; We Farm as Resistance, for Healing and Sovereignty,” Environmental Health News, May 27, 2020, ➝; Kyle Powys Whyte, “Food Sovereignty, Justice, and Indigenous Peoples,” in The Oxford Handbook of Food Ethics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), and “Settler Colonialism, Ecology, and Environmental Injustice,” Environment and Society 9, no. 1 (2018): 125–144.

I have argued this in more detail in “Labor in the Logistical Drawing,” Log 34 (2015): 139–142.

The Green New Deal Superstudio is a key example of this kind of work; 479 of 671 archived projects dealt with soil and agricultural transformation. For further details, see ➝. For more on how architects can and might understand the ambitions of the Green New Deal, see Billy Fleming, “Design and the Green New Deal,” Places Journal, April 16, 2019, ➝; Reinhold Martin, “Abolish Oil,” Places Journal, June 2020, ➝; Sam Velasquez, “Green and New,” Urban Omnibus, October 29, 2020, ➝.

Pierre Barral, Les agrariens français de Méline à Pisani (Paris: Armand Colin, 1968), 241.

John Bulaitis, Communism in Rural France: French Agricultural Workers and the Popular Front (London: I.B. Tauris, 2008), 106.

See Mary McLeod, “‘The country is the other city of tomorrow’: Le Corbusier’s Ferme Radieuse and Village Radieux.” In: Food and the City: Histories of Culture and Cultivation, ed. Dorothée Imbert (Cambridge: Dumbarton Oaks and Harvard University Press, 2014).

For more details on this project of Perriand’s, see Gabrielle de la Selle and Max Bonhomme, “La Grande Misère de Paris par Charlotte Perriand,” Photographie arme de classe: La photographie sociale et doucmentaire en France, 1928-36 (Paris: Centre Pompidou, 2018) and Romy Golan, Muralnomad : The Paradox of Wall Painting, Europe 1927-1957 (Yale University Press, 2009): 150-162.

For further details on this project see, Danilo Udovicki-Selb, “‘C’était dans l’air du temps’: Charlotte Perriand and the Popular Front,” in Charlotte Perriand: An Art of Living, ed. Mary McLeod (New York: Harry Abrams, 2004) and Golan, Muralnomad.

Ibid, 85.

Ibid.

The work of Jean Bossu is paradigmatic here. See Xavier Dousson, “La reconstruction du village témoin du Bosquel dans la Somme après 1940. Récit, ambitions et paradoxes d’une opération singulière,” In Situ. Revue des patrimoines 21 (July 16, 2013), ➝.

For more on the postwar history of rural modernization in France, see: Venus Bivar, Organic Resistance: The Struggle over Industrial Farming in Postwar France, Flows, Migrations, and Exchanges. (Chapel Hill: University Of North Carolina Press, 2018).

For more details, visit Our Land, Our Stories, which has links to the 2019 ebook Our Land, Our Stories, and a documentary about the site, The Meaning of the Seed (2021), ➝. See also Anita Bakshi, “The Settler Colonial Present: Contaminated Representations,” The Settler Colonial Present (e-flux Architecture, 2020), ➝.

See ➝.

See Soil Generation, “Agroecology from the People Volume 1” (2021), ➝.

Digestion is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the 2022 Tallinn Architecture Biennale, supported by the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC), the Estonian Museum of Architecture, and Friendship Products.