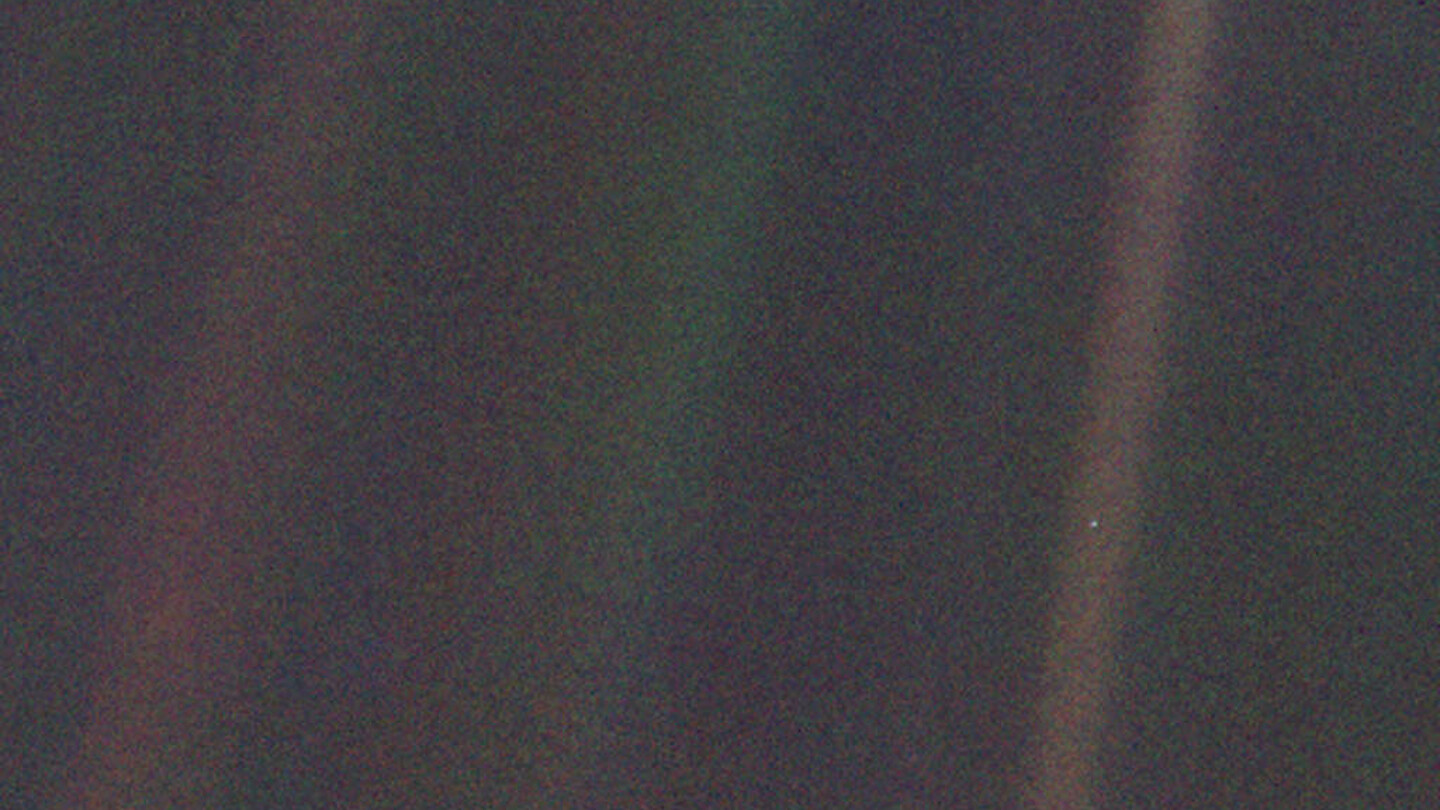

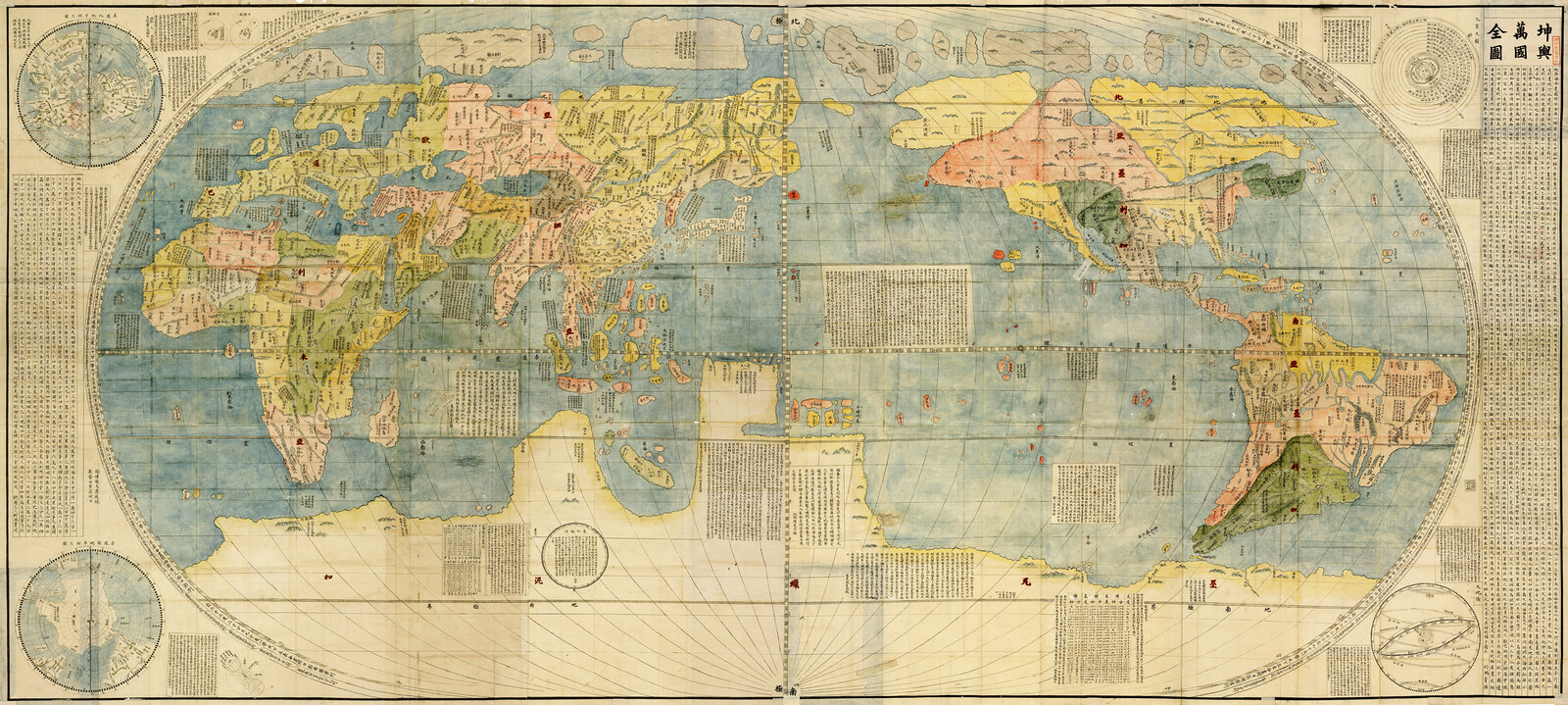

What are the sites that architecture must navigate today? How can these sites speak not only about contemporary architectural production but also of the wider socio-political relations that underpin it? This syllabus examines a set of sites through which architecture can be questioned not only as an object to observe or an interior to inhabit, but as both a vehicle for and a product of complex global forces: the infrastructures that serve it, the technologies that makes it possible, the capital it mobilizes, the labor it calls for, the environments it constructs, and the society it envisions. If the planet is confronted with interrelated concerns and common crises, this syllabus offers an alternative way of reading its multiple entanglements and partitions in order to leverage neglected resources, struggles, and histories.

As a whole, the syllabus presents inseparable spatial relations: between a world that is seamlessly connected in terms of physical, digital, and financial infrastructures and one that is simultaneously partitioned through domestic enclaves, islands of affluence, shifting boundaries, and other spatial forms of social and racial segregation. This is the context in which architects increasingly operate. On the one hand, there are a few celebrated masters, designing increasingly extravagant buildings that function as specific identities on the surface of a world almost entirely indexed by money. On the other hand, most buildings today are generated by technical, legal, and financial requirements that do not leave much room for expression. In this context, architects are called to act not only as experts unlocking the specific qualities of a given site, but also as consultants projecting abstractions onto these sites that go far beyond architectural expertise. This syllabus provides a framework aiming to both think this complexity and explore the conditions of possibility for a transformative architecture to come.

Sites are points of departure for a cogent and critical evaluation of the present by which we can begin to introduce critical forms of seeing and thinking about architecture that extend beyond the classroom. Each session focuses on a different site. These sites do not share stylistic or typological consistencies; rather they speak about spatial conditions that challenge and produce contemporary space. The sites are both generic and specific. Only through theoretical analysis can their geopolitical relations, their multiple histories, and their contradictory narratives be uncovered; in brief, the veneer of their neutrality. It is through situating their specificity that their entanglement with histories of power, of capitalism, of productive labor, of domesticity, of financialization, of automation, and of environmental concerns can be observed. To enquire into these somehow familiar spaces is to be concerned not only with understanding our present but with the possibility of re-imagining it. Thus, these sites navigate across both the specific and the generic, as well as the local and the global, the authentic and the homogenous, and the universal and the particular. One cannot simply oppose some presumed authentic locality to the homogenizing forces of globalization, just as one cannot overlook local particularities in the name of some supposedly universally applicable scheme.

Conceived as a template, the list of sites examined in each session are neither definitive nor absolute, but rather provisional and contingent. The selections that follow could be replaced by many others depending on the spatio-political reality in which and with whom such a methodology is applied. For these reasons, the sites are presented alphabetically, imagined as an open-ended assemblage. It is an invitation to unfold multiple narratives, to expose parallel conditions, to resist linear histories and to avoid defining hierarchies among them. And, yet, while the sites can be isolated, they are entangled with each other, disclosing the underlying connections and tensions that give shape to the worlds of our present. The material accompanying the sites are conceived as argumentative threads that bring together case studies, references and miscellanea. Because of the generic nature of the sites proposed, case studies should not be understood as paradigmatic or as canonical examples that in themselves create certain typological or stylistic consistencies. They speak of various forms of life, moving across different geographies and scales. For these case studies to serve as pedagogical tools, they must be contextualized not only in relation to architectural discourses, but also in relation to wider economic, cultural, political and geographical shifts. They must be understood against a network of other histories, discourses, practices, and artifacts. In doing so, we hope to contribute in writing alternative architectural histories, in which architecture does not stand alone and is not self-referential, but instead provides a history of intersections. The syllabus below is an open invitation to start this process questioning architecture as it participates in the construction of our contemporary planetary concerns.

CAMP: Sites of Suspension

As much as the planet can seem financially, environmentally, infrastructurally, and politically continuous, it is also partitioned through boundaries that differentiate subjects and their capacity to move across them. What are the spatial and temporal uncertainties of dwelling in transit? How do refugees, migrant workers, and asylum seekers dwell while in transit? How do spatial organizations of camps distribute services and resources? What are the internal and external forces shaping life within them? And how, in turn, do camps impact socio-spatial relations beyond their boundaries?

Cases

‧ Azraq Refugee Camp, 2014, Azraq, Jordan.

‧ IKEA, Better Shelter, 2015.

‧ Calais migrant camp, 2015, Calais, France.

References

‧ Andrew Herscher, “Humanitarianism Housing Question: From Slum Reform to Digital Shelter,” e-flux Journal 66 (October 2015), ➝.

‧ Didier Fassin, “Architectures of Inhospitality,” in After Belonging: The Objects, Spaces, and Territories of the Ways We Stay in Transit, eds. Lluís Alexandre Casanovas Blanco, Ignacio G. Galán, Carlos Mínguez Carrasco, Alejandra Navarrete Llopis, and Marina Otero Verzier (Zürich: Lars Müller, 2016), 162–165.

‧ Michel Agier, “Humanity as an Identity and Its Political Effects (A Note on Camps and Humanitarian Government),” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development 1, no. 1 (Fall 2010): 29–45.

Miscellanea

‧ Submarine Channel, Refugee Republic, 2012–ongoing, ➝.

CAMPUS: Sites of Knowledge

Having grown to constitute a new economy, digital platforms are also generating new forms of production sites. Many of these companies consolidate their operation in campuses, merging work and leisure, and incorporating an increasing number of activities. What are the urban implications—namely, on housing and transportation infrastructures—of corporate campuses? What ways of living (i.e. healthcare, entertainment, education, and recreation) are implied by these spaces of labor and leisure? What is the future of labor organized by large multinational corporations? What effects do cognitive capital enclaves have on the city?

Cases

‧ Hog Farm Commune, Tent City, 1972, Skarpnäck, Sweden.

‧ Foster and Partners, Apple Campus, 2017, Cupertino, California, USA.

‧ Google Hudson Square Campus, 2018–ongoing, New York City, USA.

References

‧ Lina Malfona, “The Circle: Geographies of Network vs. Geometries of Disjunction,” Avery Review 30 (March 2018), ➝.

‧ Felicity Scott, “Woodstockholm,” in Outlaw Territories: Environments of Insecurity/Architectures of Counterinsurgency (Brooklyn: Zone Books, 2016), 115–166.

‧ Nick Srnicek, Platform Capitalism (Cambridge and Malden: Polity Press, 2016), 9–35.

Miscellanea

‧ David Fincher, director, The Social Network, 2010, film.

CLOUD: Site of Computation

In a world of ubiquitous computing and networked information technology, the spatiality and materiality of its distributed power remains largely overlooked. While architecture is increasingly shaped by computation, the architectures that host the computational stack in which we live has yet to be critically analyzed. What are the physical and digital infrastructures that support our ever growing and expanding networked ecologies? From phone to data center to cloud and back again, how do we begin to identify and understand the computational and the material supports that enable continuous connectivity, and what are the architectural opportunities and challenges of designing such infrastructure?

Cases

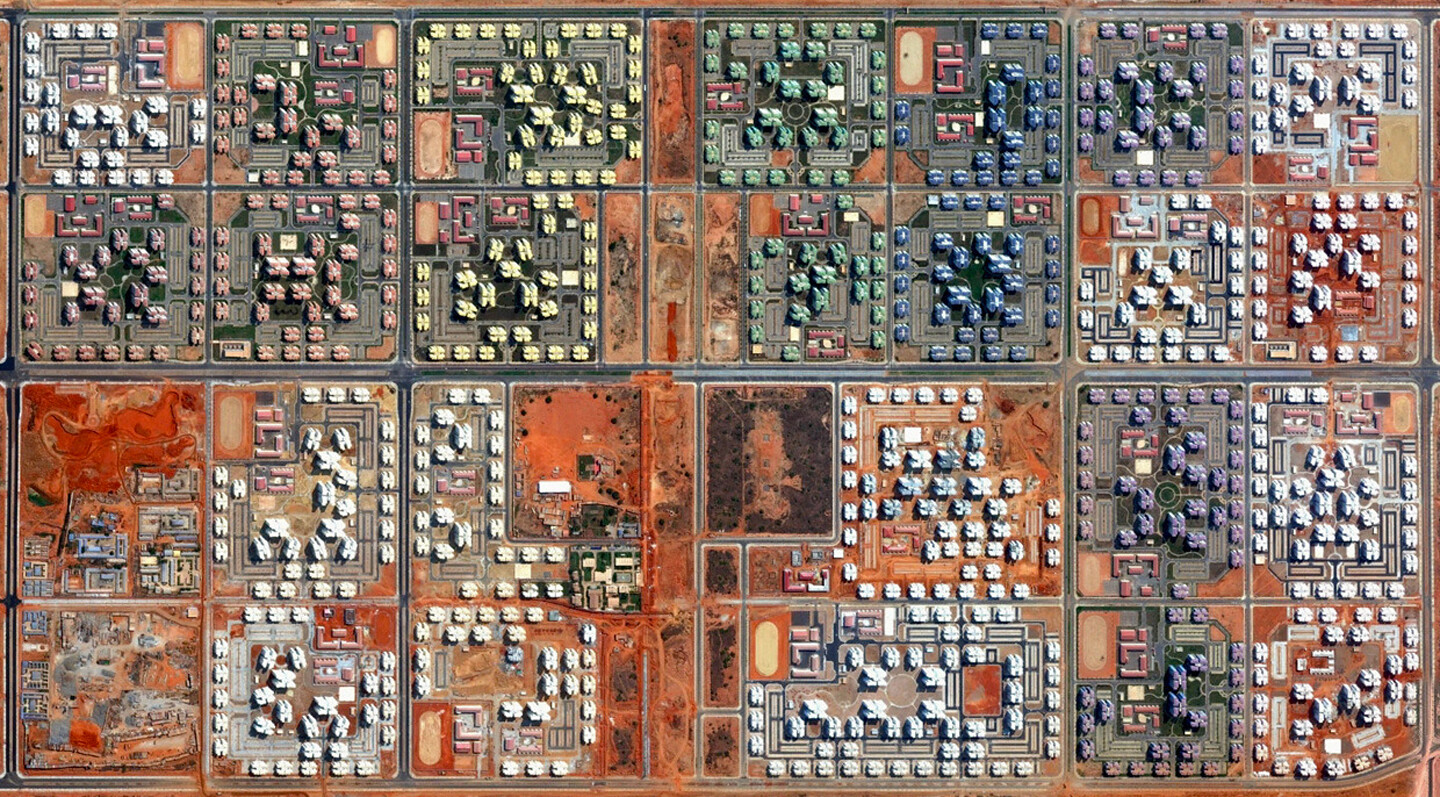

‧ Songdo International Business District, Smart City, 2010, Incheon, South Korea.

‧ Sidewalk Labs, Sidewalk Toronto, 2017–ongoing, Toronto, Canada.

‧ Apple and Facebook Data Centers, 2017–ongoing, Des Moines, Iowa, USA.

References

‧ Benjamin H. Bratton, “The Stack,” Log 35 (Fall 2015): 129–159.

‧ Orit Halpern, “Test Bed Urbanism,” Public Culture 25, no. 2 (2013): 273–306.

‧ Adam Greenfield, “Smartphone: The Networking of the Self,” in Radical Technologies: The Design of Everyday Life (London: Verso, 2017).

Miscellanea

‧ Trevor Paglen, photographs of network infrastructure, 2016–ongoing.

DESK: Sites of Cognitive Labor

What are the limits of work, and what are its spaces? How has the spatial organization of desks as the site of immaterial labor, as the specific domain of white collar work, transformed standards of productivity and personal expectations? By tracing a brief history on the relation between architecture and immaterial labor from the postwar to the present, we can explore how the re-imagination of the sites of immaterial labor have transformed not only office spaces but also the city itself.

Cases

‧ Eberhard and Wolfgang Schnelle, Bürolandschaft, 1950s.

‧ Hans Hollein, Mobile Office, 1969.

‧ DOGMA, Everyday is Like Sunday, 2015, Zaventem, Brussels and Zellik, Belgium.

References

‧ Maurizio Lazzarato, “Immaterial Labor,” in Radical Thought in Italy: A Potential Politics, eds. Paolo Virno and Michael Hardt (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 133–146.

‧ Shannon Mattern, “Sharing is Tables: Furniture for Digital Labor,” Positions (e-flux Architecture, October 9, 2017), ➝.

‧ Andreas Rumpfhuber, “Leisure as the Extended Field of Labor,” in Into the Great Wide Open (Barcelona: DPR Barcelona, 2017), 19–32

Miscellanea

‧ Christian Marclay, The Clock, 2010, video.

FACTORY: Sites of Production

The “post-industrial” world in which iconic architectural projects have proliferated in the past decades has proven to be little more than a western-centric myth. Industrial production remains ubiquitous; from “Foxconn City” in Longhua China to the Maquiladoras along the northern Mexican border, factories are growing. Given the tendency within architecture to marginalize these spaces from architectural knowledge and design, how can the factory reclaim its position within architectural discourse and production in a way that moves beyond speculative interventions in the landscapes left behind by modern industry? How do local and regional issues of gentrification, real estate speculation, and segregation speak to geopolitical processes of invisible labor and outsource manufacturing?

Cases

‧ Inner Harbor, 1976–ongoing, Baltimore, USA.

‧ Lounghua Science and Technology Business Park “Foxconn City,” 1988–ongoing, Shenzhen, China.

‧ HafenCity, 2002–ongoing, Hamburg, Germany.

References

‧ Joshua B Freeman, “Foxconn City,” in Behemoth: A history of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World (New York: Norton Company, 2018), 270–312.

‧ David Harvey, “A view from Federal Hill,” in The Baltimore Book: New Views on Urban History, eds. Elizabeth Fee, Linda Shopes, and Linda Zeidman (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991), 227–249.

‧ Neil Smith, “The evolution of gentrification,” in Houses in Transformation: Interventions in European Gentrification, eds. Jaap Jan Berg, Tahl Kaminer, Marc Schoonderbeek, and Joost Zonneveld (Rotterdam: NAI Publishers, 2008), 15–26.

Miscellanea

‧ Wang Bing, Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks, 2003, video.

GALLERY: Sites of Exhibition

As museums have become the primary program for architectural expression and the circulation of cultural capital, the gallery has progressively moved outside the artworld to colonize other domains, from commerce to housing. What does the ubiquitous position of the white cube in both art and architecture reveal about our contemporary exhibitionary complex? With the relocation of industrial production to the Global South, and the more generic figure of the gallery gaining a new prominence in the West, what futures does the white cube offer our collective desire for blank space?

Cases

‧ Philip L. Goodwin and Edward Durell Stone, 1939, MoMA, New York, USA

‧ Lacaton & Vassal, Palais de Tokyo, 2012–2014, Paris, France.

‧ OMA, The White Cube, 2017, Lusanga, DRC.

References

‧ Brian O’Doherty, “Notes on the Gallery Space,” in Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of The Gallery Space (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999 [1986]), 13–35.

‧ Jeremy Lecomte, “Blank Space: About the White Cube and the Generic Condition of Contemporary Art,” in Theatre, Garden, Bestiary, A Materialist History of Exhibitions, eds. Tristan Garcia and Vincent Normand (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2019).

‧ Kai Bosworth and Steve Lyons, “Museums in the Climate Emergency,” in Museum Activism, eds. Robert R. Janes and Richard Sandell (New York: Routledge, 2019).

Miscellanea

‧ Andrea Fraser, Little Frank and his Carp, 2001, video.

HOME: Sites of Ownership

In liberalized economies, a home is not only a shelter, a site of intimacy, of rest and belonging. It is also an investment, a desire, a debt, a right, a means of regulation, administrative control, and social standing. The confluence of these issues at the site of housing make it a rich and complex site of enquiry. Given the range of material, spatial, formal, and contextual qualities, everything from high-end condos and communal living to single family homes and micro dwellings share a common history within a narrative of global capital. How can we understand the home as more than a site of architectural intervention and experimentation? Beyond its spatial qualities and contextual relations, what are its financial, legal, administrative, cultural, and social dimensions?

Cases

‧ Le Corbusier and Max du Bois, Maison Dom-ino, 1914.

‧ Housing and Development Board, Block 838, 1970s, Yishun, Singapore.

‧ Tatiana Bilbao, Ciudad Acuña, 2014, Coahuila, Mexico.

References

‧ Markus Hesse, “Into The Ground. How the financialization of property markets and land use puts cities under pressure,” ARCH+ 231 (Spring 2018): 78–83.

‧ Ivonne Santoyo-Orozco, “From the Right to Housing to the Right of Credit. The Drama of Ownership in Mexico,” in A House is Not Just a House, ed. Isabelle Kirkham-Lewitt (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City. 2018), 114–135.

‧ Peter Marcuse and David Madden, “Contradictions of Urban Renewal,” in Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis (New York: Verso, 2016).

Miscellanea

‧ Mercedes Alvarez, Mercado de Futuros, 2011, video.

PIT: Sites of Extraction

How do we image nature today? What are the representational regimes that dominate its production? What material demands does global capitalism place on our planetary resources and natural reserves? What are the histories and futures of material life cycles (i.e. production, consumption, waste) required by planetary urbanization and financial speculation? What are the spatial effects of extraction, understood here in a wide sense, including, but not limited to: fisheries, forestry, agriculture, mineral mining, oil mining, hydroelectric power, wind farming, solar harvesting, etc? What systems enable and support the extractive practices, colonial activities, and transportation infrastructures that claim and make territory?

Cases

‧ Neme Studio, Nine Islands, 2016.

‧ Lateral Office, States of Disassembly, 2017.

‧ Kadambari Baxi, Jordan H. Carver, Laura Diamond Dixit, Lindsey Wikstrom Lee, and Mabel O. Wilson with Tiffany Rattray and Beth Stryke, Who Builds Your Architecture? A Critical Field Guide, 2017, ➝.

References

‧ Meredith Miller, “Views from the Platisphere: A Preface to Post-Rock Architecture,” in Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary, eds. James Graham, Caitlin Blanchfield, Alissa Anderson, Jordan Carver, and Jacob Moore (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City and Lars Müller Publishers, 2016), 68–78.

‧ Pierre Bélanger, ed., Extraction Empire: Undermining the Systems, States, and Scales of Canada’s Global Resource Empire, 2017—1217 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017).

‧ James Graham, “Making Coal Historical (a Road Trip),” Avery Review 35 (December 2018), ➝.

Miscellanea

‧ Jia Zhangke, director, Still Life, 2006, film.

RESERVE: Sites of Preservation

In times confronted with an unprecedented ecological crisis, how are natural reserves defined? What is reserved in the reserve and what is not in turn? How are their boundaries determined, drawn, and modified? How is nature defined? Who has the right to live, access, monitor, profit from, and administer the spaces and resources of a reserve? In which ways does the reserve reflect or contradict forms of urban living beyond its boundaries? In what role do reserves play in the construction and maintenance of global environmental imaginaries? How do these techniques developed in the enclosure of reserves translate in turn to techniques that we can find in emerging practices of design?

Cases

‧ Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, 1868, North Dakota, USA.

‧ Forest Conservation Act, 1980, India.

‧ Yasuní National Park, 1989, Kichwa Añangu, Ecuador.

References

‧ Ana María Durán Calisto. “For the Persistence of the Indigenous Commune in Amazonia,” Overgrowth (e-flux Architecture, February 5, 2019), ➝.

‧ Alon Schwabe, Daniel Fernández Pascual, and Forager Collective, “The Forest Does Not Employ Me Anymore,” in Cooking Sections, The Empire Remains Shop (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2018), 29–34.

‧ Nick Estes, “Fighting for Our Lives: #NoDAPL in Historical Context,” The Red Nation, September 18, 2016, ➝.

Miscellanea

‧ Les Blank, director, Burden of Dreams, 1982, film.

RESORT: Sites of Tourism

Architecture has a complicit relation with the history of tourism. Architecture as destination has increasingly gained geopolitical relevance as its shares its history with that of the tourist industry; an industry whose history dovetails with histories of post-colonialism, exoticism, resource extraction, mobility, and labor migration. What, then, is a resort, and what are the histories of these spaces? How has architecture given visibility to the resort, and how has the resort given rise to the tourist industry? How has the resort been superseded by other spatial diagrams, or has begun to inhabit other spatial sites?

Cases

‧ Florestano di Fausto, Uaddan Hotel and Casino, 1935, Tripoli, Libya.

‧ Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio, SuitCase Studies: The Production of a National Past, 1991, installation, Walker Art Center.

‧ Rem Koolhaas, letters regarding The Dalieh of Raouche, Lebanon, 2015, ➝.

References

‧ AMO, “Context,” in Rem Koolhaas, ed., Content (Köln: Taschen, 2004), 96–105.

‧ Boris Groys, “The City in the Age of Touristic Reproduction,” in Art Power (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2009), 101–110.

‧ Brian McLaren, “Colonial Tourism and the Experience of Modernity,” in Architecture and Tourism in Italian Colonial Libya. An Ambivalent Modernism (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006), 43–78.

Miscellanea

‧ Armin Linke, Alpi, 2011, video.

SHED: Sites of Logistics

From data centers and automated processing lines to the protocols and sensing devices enabling the diffusion of what is now called the “internet of things,” logistics has expanded its realm, its meaning, and its role in the global economy. Information technology is indifferent to architectural specificity, thus eliminating the need for design. If logistics designs buildings, landscapes, and infrastructures according to cost, size, and technical requirements, is the generic category of the shed a harbinger of architectural production in an age of automation?

Cases

‧ Walmart, 1950–present.

‧ Google Data Centre, 2009–2014, Hamina, Finland

‧ Amazon Logistics Center, 2018, San Bernardino, USA.

References

‧ Jesse Le Cavelier, The Rule of Logistics. Walmart and the Architecture of Fulfillment (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016).

‧ Yossi Sheffi, Logistics Clusters, Delivering Value and Driving Growth (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2012).

‧ Victor Muñoz Sanz, “Researching Automated Landscapes,” in Work, Body, Leisure, Marina Otero Verzier and Nick Axel, eds. (Italy: Hatje Cantz, 2018), 103–113.

Miscellanea

‧ Robert Wyatt, Pigs… (in there), 1993, song.

SLUM: Sites of Uneven Development

What defines a slum and why have they received such interest from design practitioners? Is the word “slum” the most accurate and productive analytical category to characterize the plurality of urban practices and diversity of dwellings, environments, and habitats that follow from what can otherwise be described as unplanned modes of settlement? What consequences do such “tactical urbanisms” have on the distribution and access to public space, housing, mobility, health care, education, and work, and how can environmental conditions and issues of spatial justice be improved at a range of scales through policy and design interventions? Are slums really a reservoir of innovative ideas to move beyond planning? Or are they, on the contrary, symptoms showing how much planning needs to be recalled and rethought?

Cases

‧ Robert Taylor Homes, 1961, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

‧ Slum Rehabilitation Scheme, 2003–ongoing, Dharavi, Mumbai, India.

‧ Urban Think Tank, Metro Cable, 2010, Caracas, Venezuela.

References

‧ Reinhold Martin, “Financial Imaginaries; Toward a Philosophy of the City,” Grey Room 42 (2011): 60–79.

‧ Ananya Roy, City Requiem, Calcutta: Gender and the Politics of Poverty (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2002).

‧ Saskia Sassen, “Beyond Inequality: Expulsions,” in: Critical Perspectives on the Crisis of Global Governance, Stephen Gill (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 69–88.

Miscellanea

‧ Adam Curtis, 40 Minutes: Bombay Hotel, BBC Two, 1987, video.

SQUARE: Sites of Publics

The square is one of the most paradigmatic sites of politics, yet one whose history has shifted dramatically over the past century. Neoliberal privatization marked not only a new economic paradigm but also an urban one. Increasingly, many local institutions and basic services crucial for the management of urban life became sites of compromise, partnership, and negotiation between public and private interests. Alongside concerns of finance and urban management, this transformation presses on political urgencies, such as inclusivity, equality, and tolerance. What relevance does the square have today, at a time when so much social and political exchange takes place off-site and online? What do contemporary spaces used for gathering, leisure, and demonstration tell us about public space and participation today?

Cases

‧ Lina Bo Bardi, MASP, 1957-1968, São Paulo, Brazil.

‧ Andrés Jaque, Ikea Disobedients, 2011.

‧ Eyal Weizman, Ai Wei Wei, Peter Eisenman, et al., Gwangju Folly Project, 2013.

References

‧ Dolores Hayden, “Domesticating Urban Space,” in Redesigning the American Dream (New York: W.W. Norton), 225–238.

‧ Anna Minton, Ground Control: Fear and Happiness in the Twenty-First-Century City (London: Penguin, 2012).

‧ Adrian Blackwell, “Tar and Clay: Public Space Is the Demonstration of a Paradox in the Physical World,” in Public Space? Lost & Found, eds. Gediminas Urbonas, Ann Lui, and Lucas Freeman (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017), 19–38.

Miscellanea

‧ Marisa González, Ellas Filipinas, 2012, documentary.

TERMINAL: Sites of Mobility

Mobility and its associated techno-positivist ideals have become unconscious cultural fetishes. But what does mobility mean exactly in terms of global and local transportation infrastructures, including but not limited to: streets, sidewalks, subway stations, train stations, airport terminals, ferry terminals, airports, and other formal and informal modes of transportation? What practices and techniques of control enable or prohibit the freedom of movement, passage, and migration in an unevenly distributed post-national geopolitical landscape? What are the economic, political, psychological, and social costs of restricting one’s freedom of movement? And how do terminals participate in the invention of future transportation?

Cases

‧ Luis Callejas, Heathrow Airplot: Weightlesss, 2010, London, England.

‧ Foster + Partners, FR-EE, and NACO, Mexico City International Airport, 2014, Mexico City, Mexico.

‧ Norman Foster Foundation, Droneport, 2016, Rwanda.

References

‧ Ana María León, “Air Nationalism: Norman Foster and Fernando Romero’s Mexico City Airport,” Avery Review 2 (October 2014), ➝.

‧ Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson, “Zones, Corridors, and Postdevelopmental Geographies,” in Border as Method, or, the Multipplication of Labor (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2013), 205–242.

‧ Hannah Appel, Nikhil Anand, and Akhil Gupta, “Temporality, Politics, and the Promise of Infrastructure,” in The Promise of Infrastructure (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2018), 1–31.

Miscellanea

‧ Allan Sekula, Fish Story, 1995, video.

WATERFRONT: Sites of Environmental Speculation

The development of coastlines, riverbanks, and lakeside properties has intensified as sites investment, growth, and real estate speculation throughout the world. For many architects, these sites offer a canvas for design invention filled with sunset fantasies and colorful promenades. Yet behind this picture lies another story, one that not only intersects with real estate speculation, but also with the global threat of sea level rise. The meeting of these two narratives yields a contradiction: the consumption of nature that is manifest in planetary urbanization, the rampant extraction and circulation of resources, and the degradation of the natural world produces effects that now threaten the very coastlines that developers seek to exploit. How does architecture make visible or invisible these contradictions?

Cases

‧ Kunlé Adeyemi, Makoko Floating School, 2008, Lagos, Nigeria.

‧ BIG, OMA, Interboro Partners, et al., Rebuild by Design Hurricane Sandy Design Competition, 2014.

‧ Seasteding Institute, 2017–ongoing.

References

‧ Ross Exo Adams, “Notes from the Resilient City,” Log 32 (2014): 126–139.

‧ Stephanie Wakefield, “Oystertecture: Infrastructure, Profanation, and the Sacred Figure of the Human,” in Infrastructure, Environment, and Life in the Anthropocene, ed. Kregg Hetherington (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019).

‧ Ashley Dawson, Extreme Cities: The Peril and Promise of Urban Life in the Age of Climate Change (London: Verso, 2017).

Miscellanea

‧ David Simon and Erik Overmyer, Treme, HBO, 2010-2013, TV series.

Theory’s Curriculum, a project by e-flux Architecture and Joseph Bedford, is produced with the support of the Global Architectural History Teaching Collaborative; Virginia Tech Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, College of Architecture and Urban Studies, and School of Architecture + Design; School of Architecture, Syracuse University; John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design, University of Toronto; Department of Architecture, Wentworth Institute of Technology; and Department of Architecture, Iowa State University College of Design. Special support for the project in its initiation, fundraising, and guidance was provided by Joseph Godlewski.