Every night on this planet, about six percent of humans sleep in tents. We can guess this figure based on the 1.6 billion who lack adequate housing and the 150 million who are homeless. We must also include the 65 million forcibly displaced people: refugees of war, climate change, economics or politics, and asylum seekers of every kind.

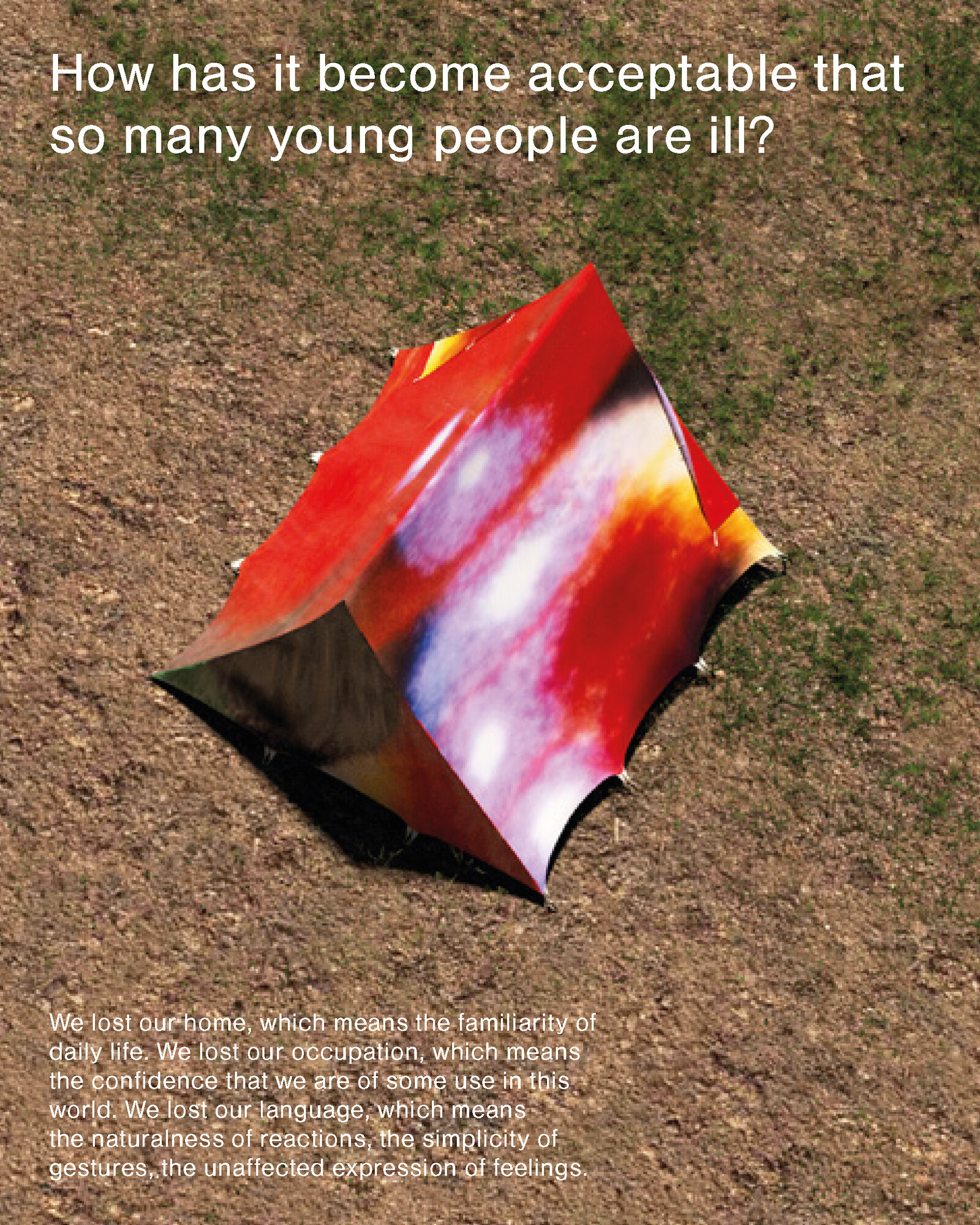

Some of the world’s tents are privately owned, others are provided by humanitarian agencies, others paid for by nation-states. Some tents are marshalled in camps, some are clustered by wasteland. A percentage move location every night, but the vast majority are immobile—a typical refugee spends more than a decade sleeping in one tent, in one camp.

Tents are as old as humanity; the Cro-Magnon made mammoth-skin structures at least 40,000 years ago. When the tent was invented, probably during the Late Paleolithic, it was at a time of primitive communitarian nomadism—before such concepts as property, ownership, territory, or family. The tent is thus an essential instrument of human mobility, liberty, and oneness with the natural order.

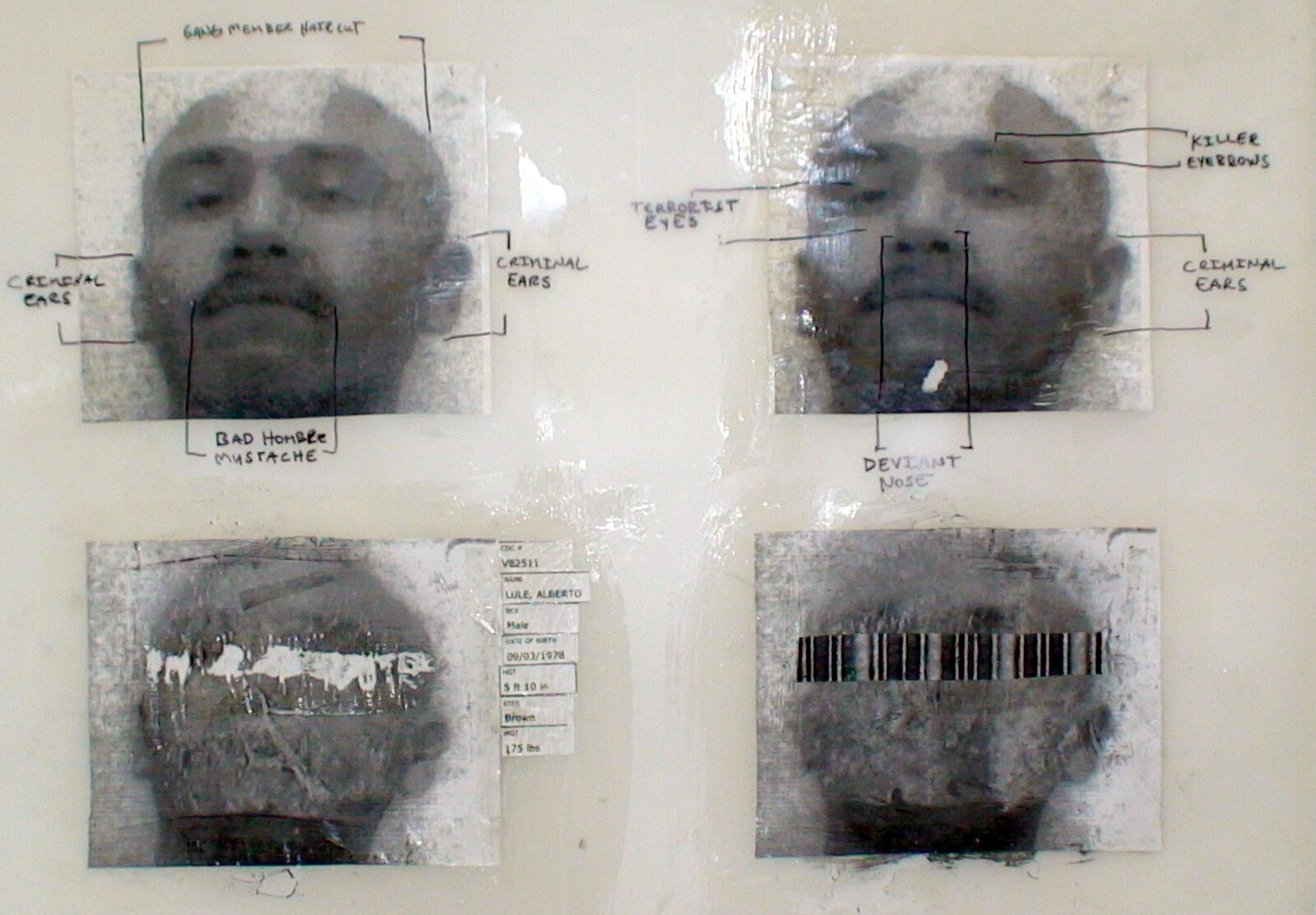

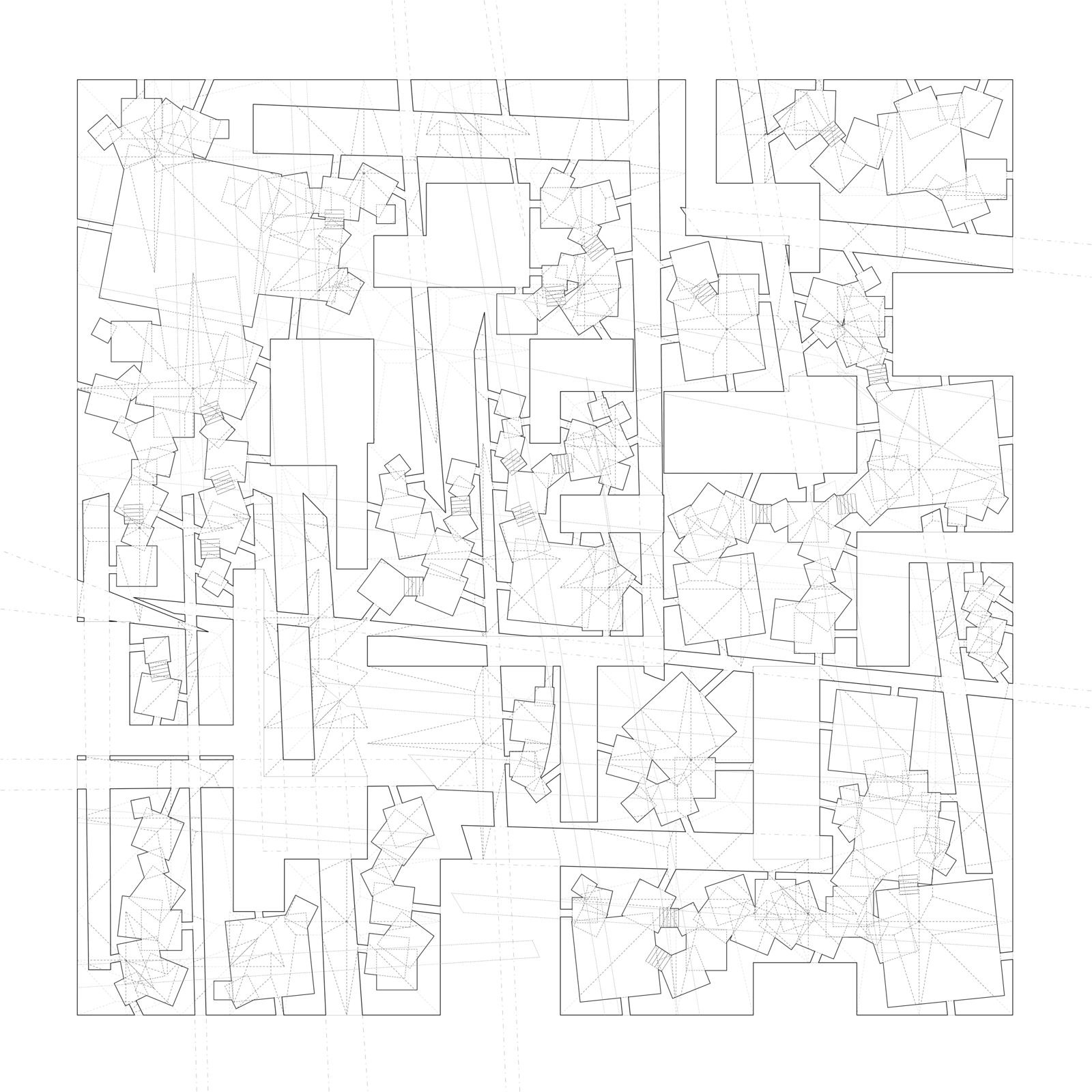

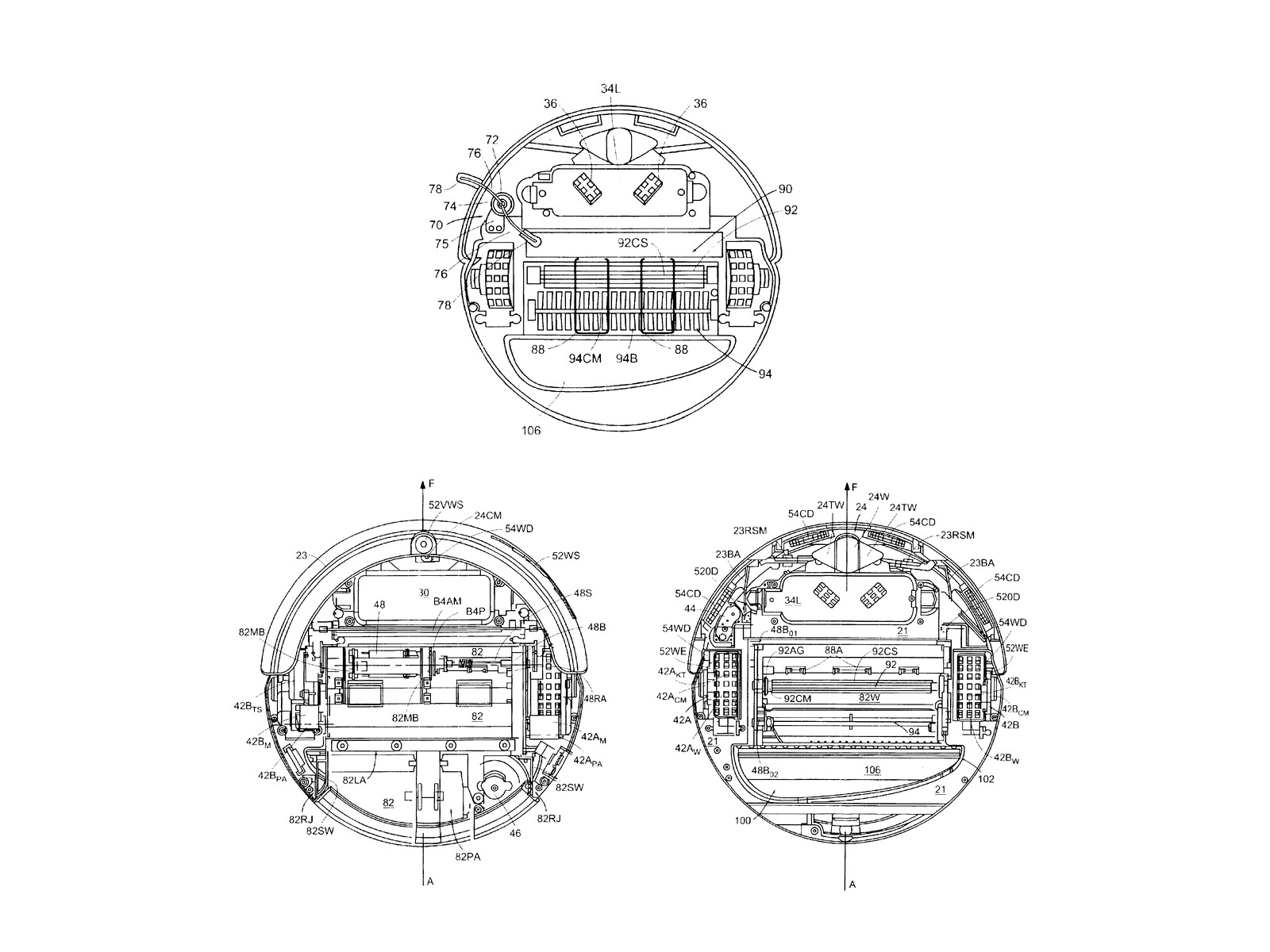

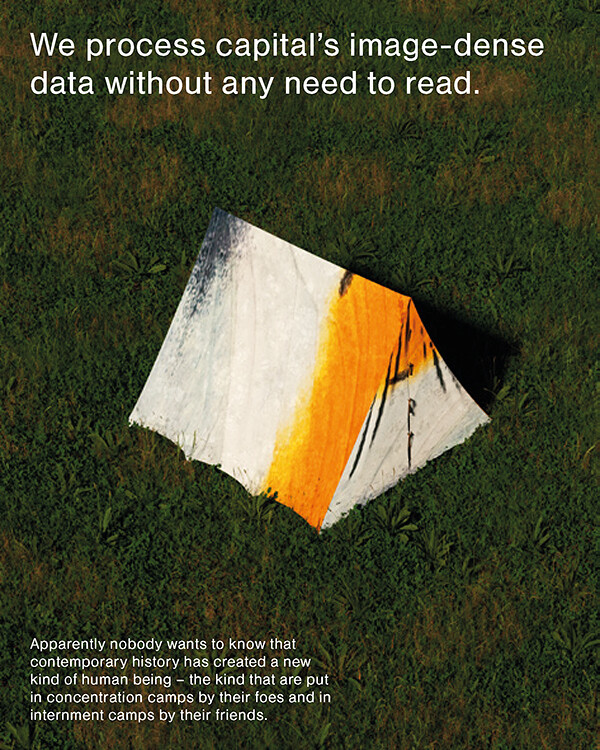

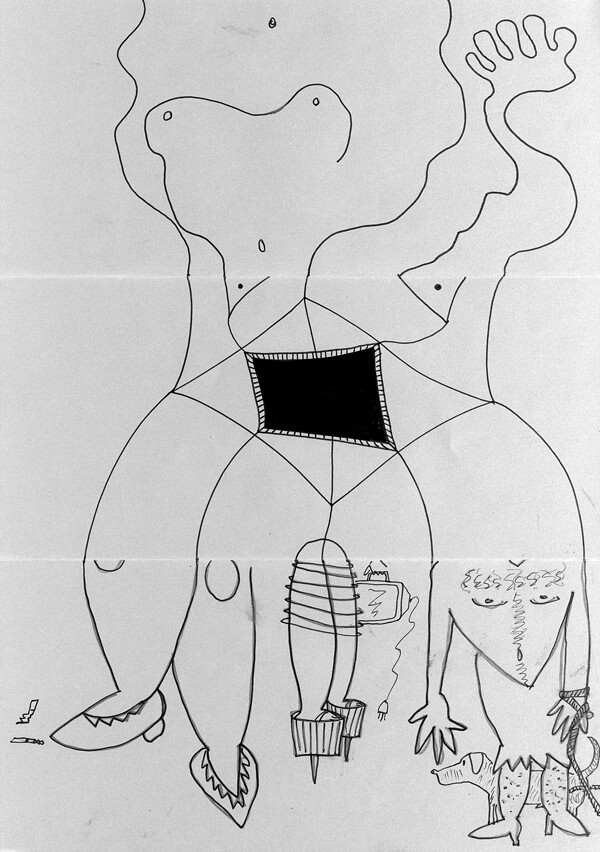

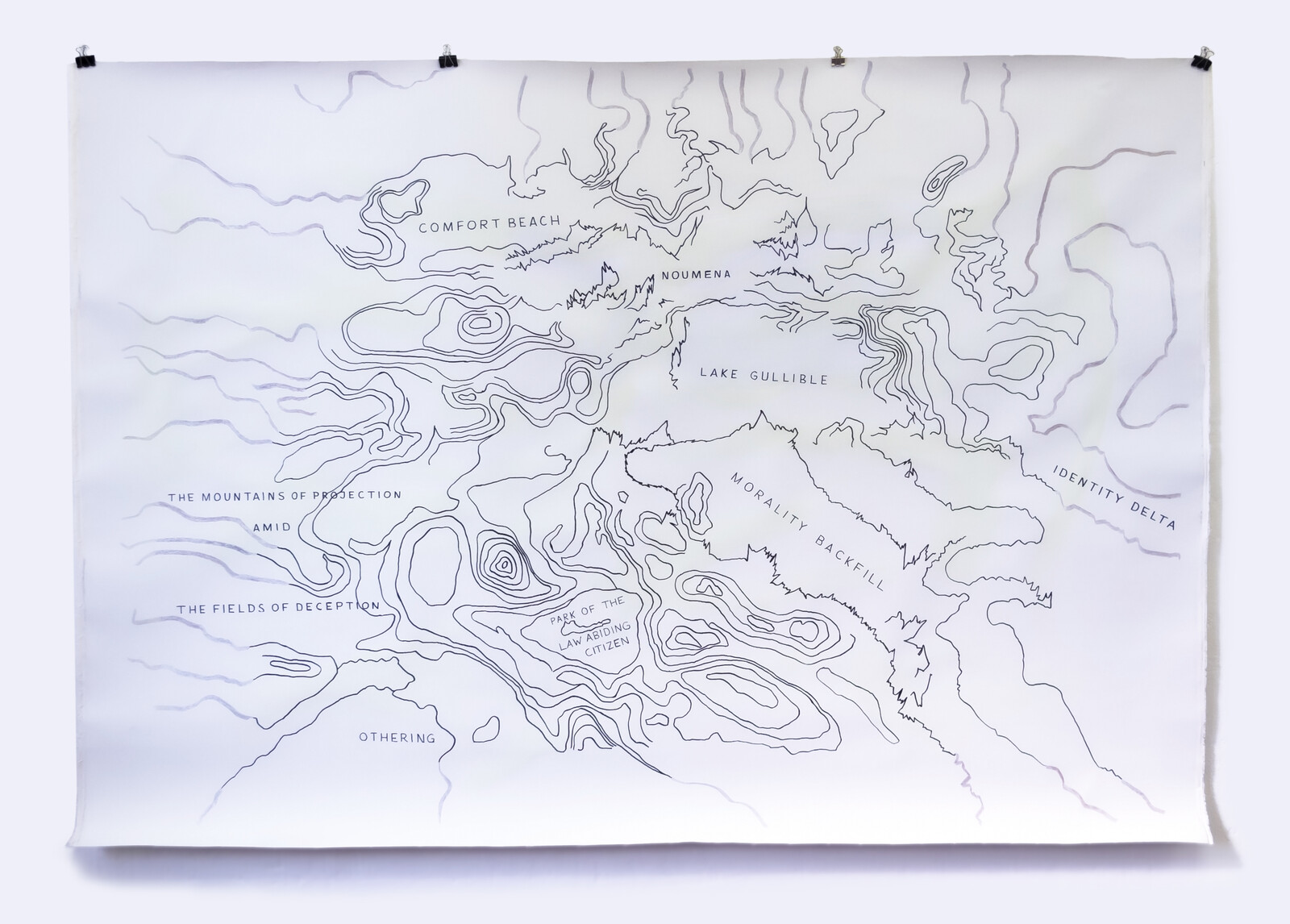

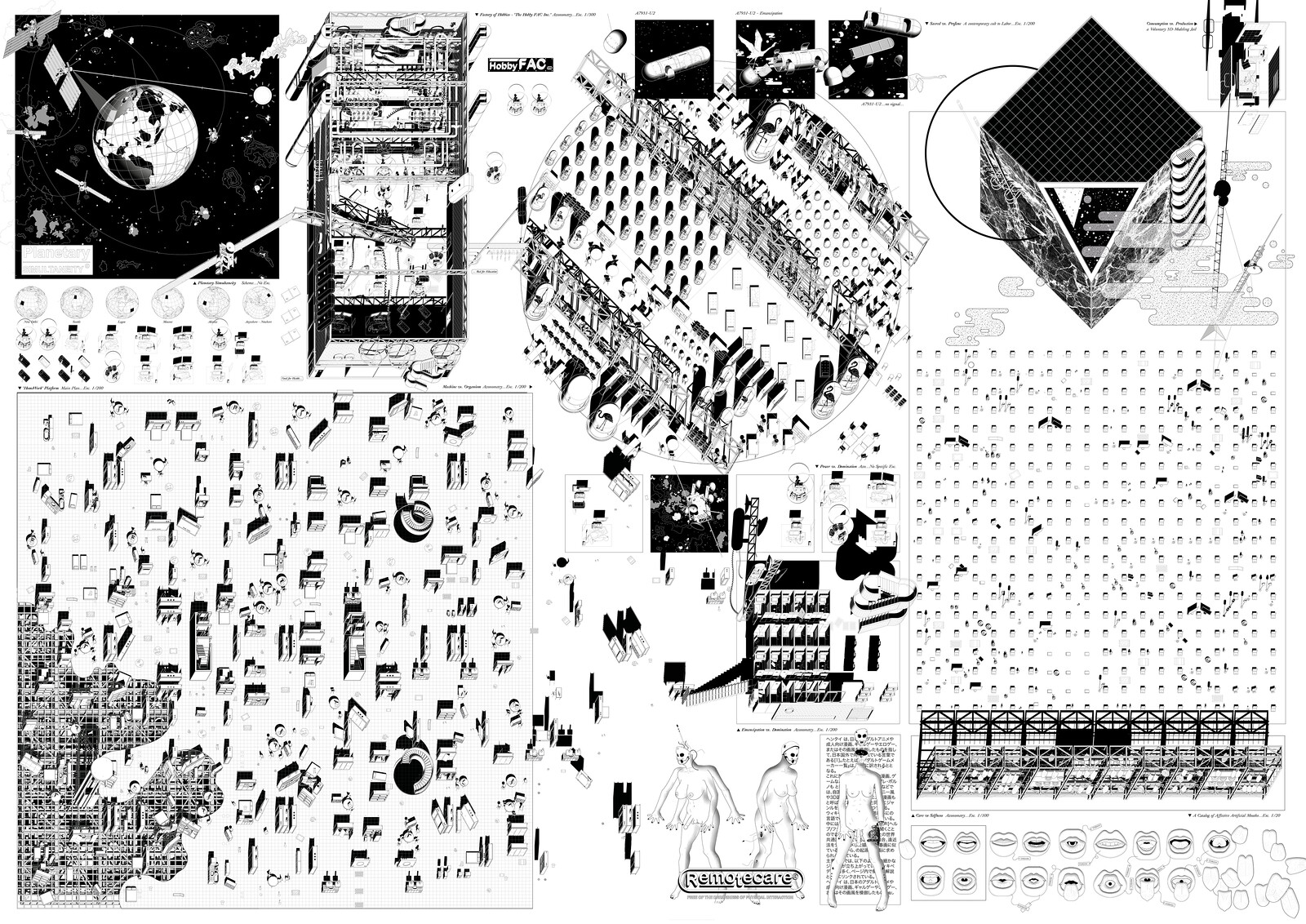

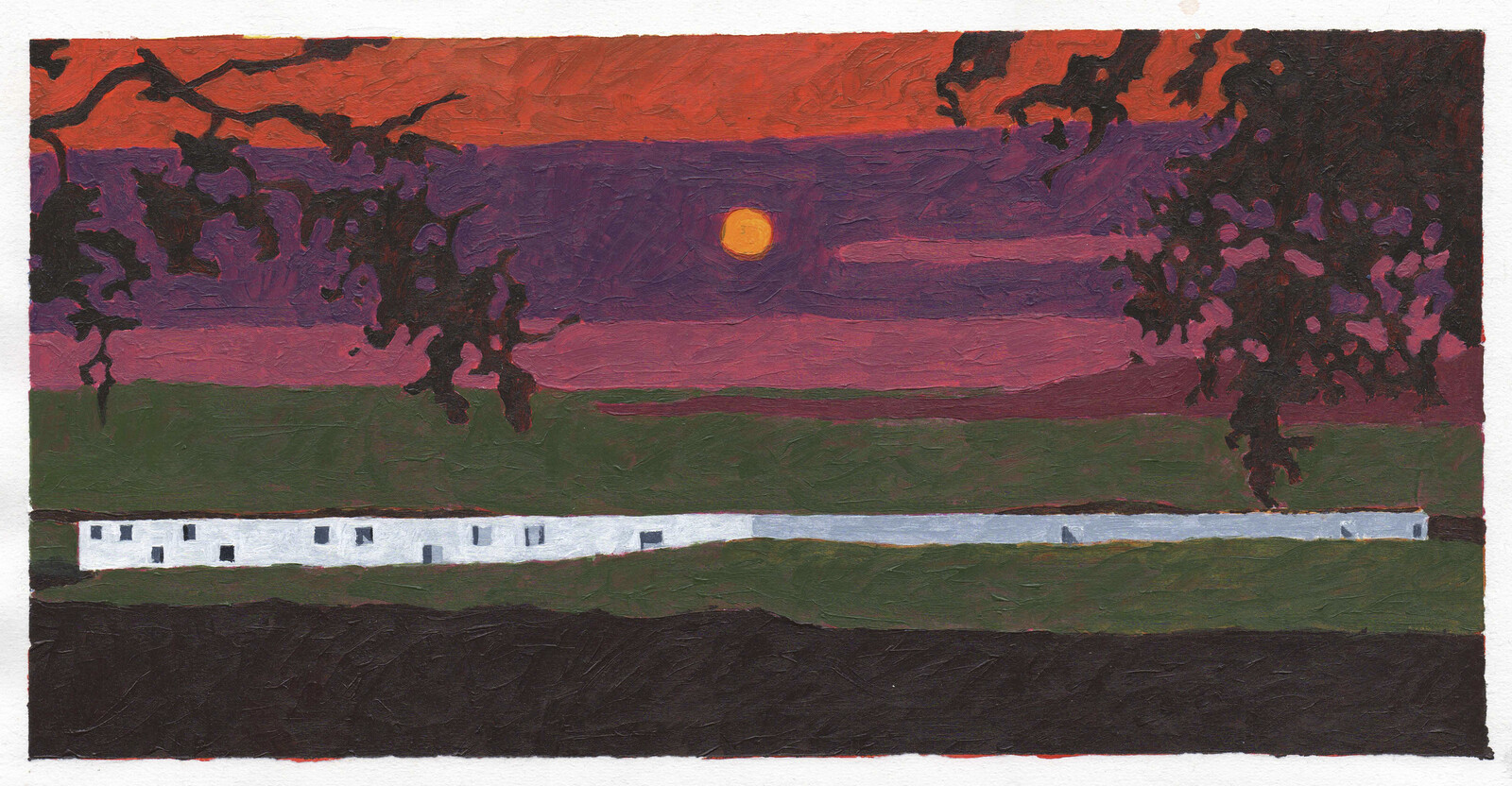

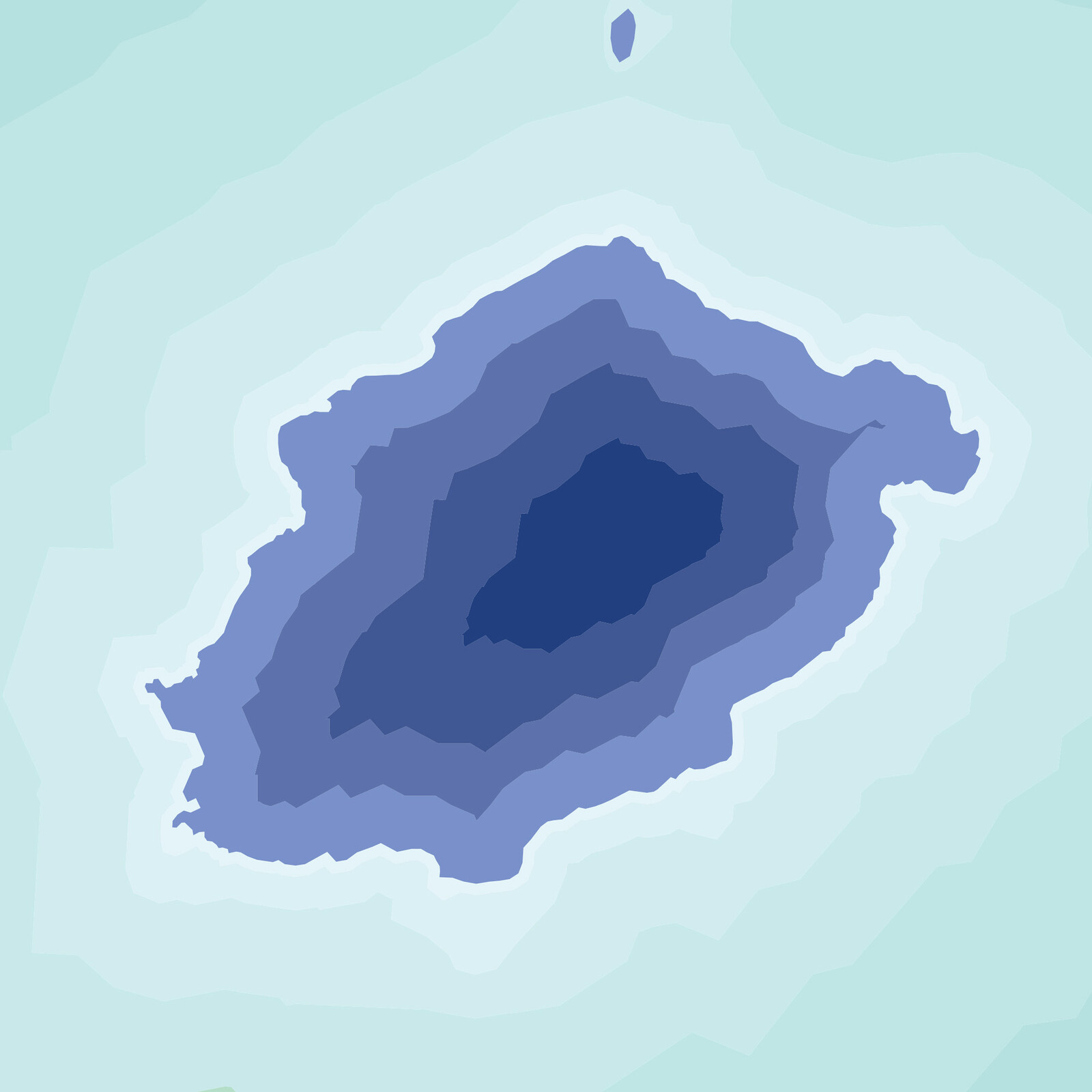

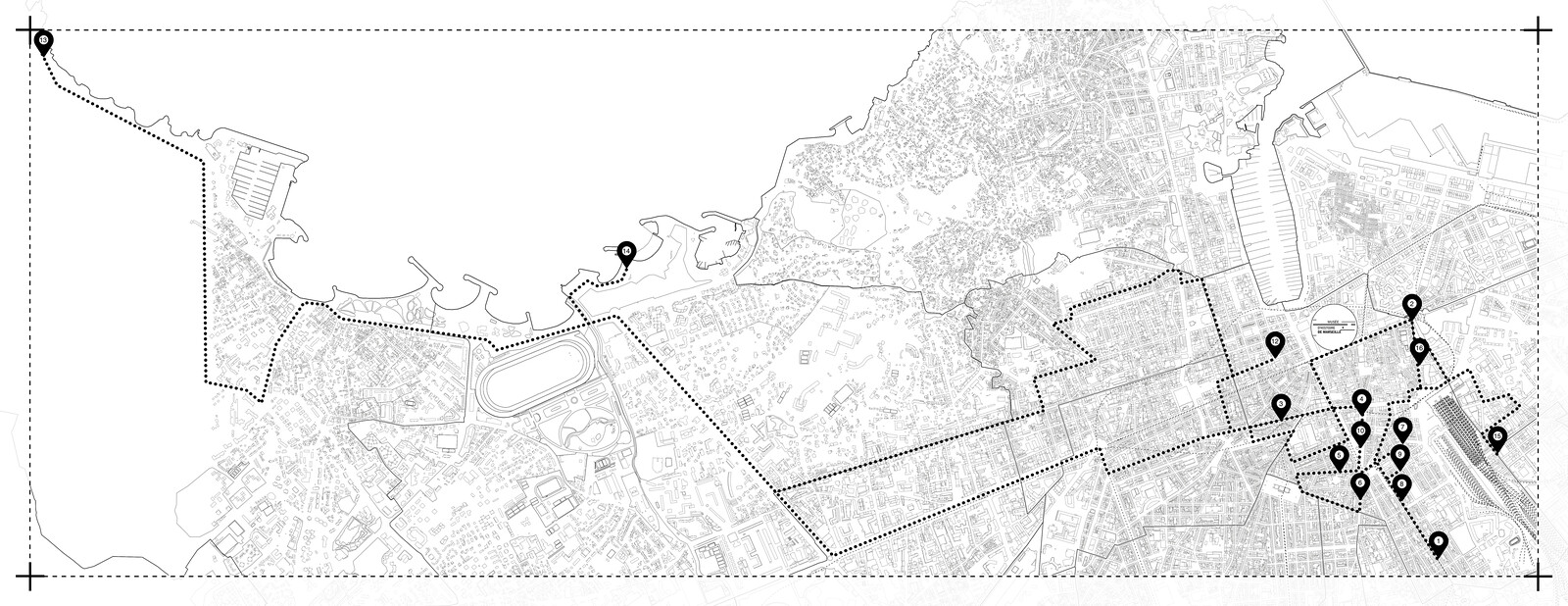

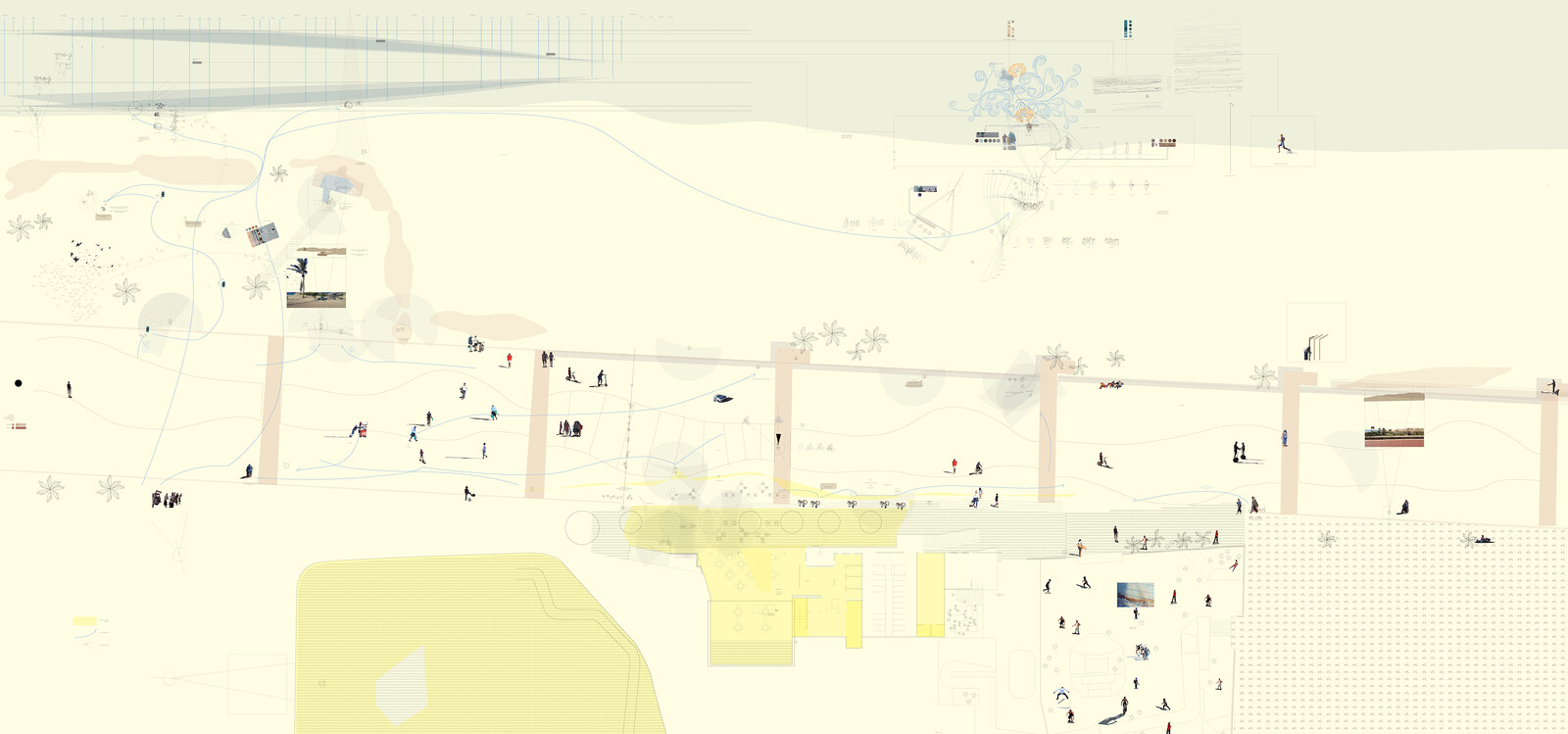

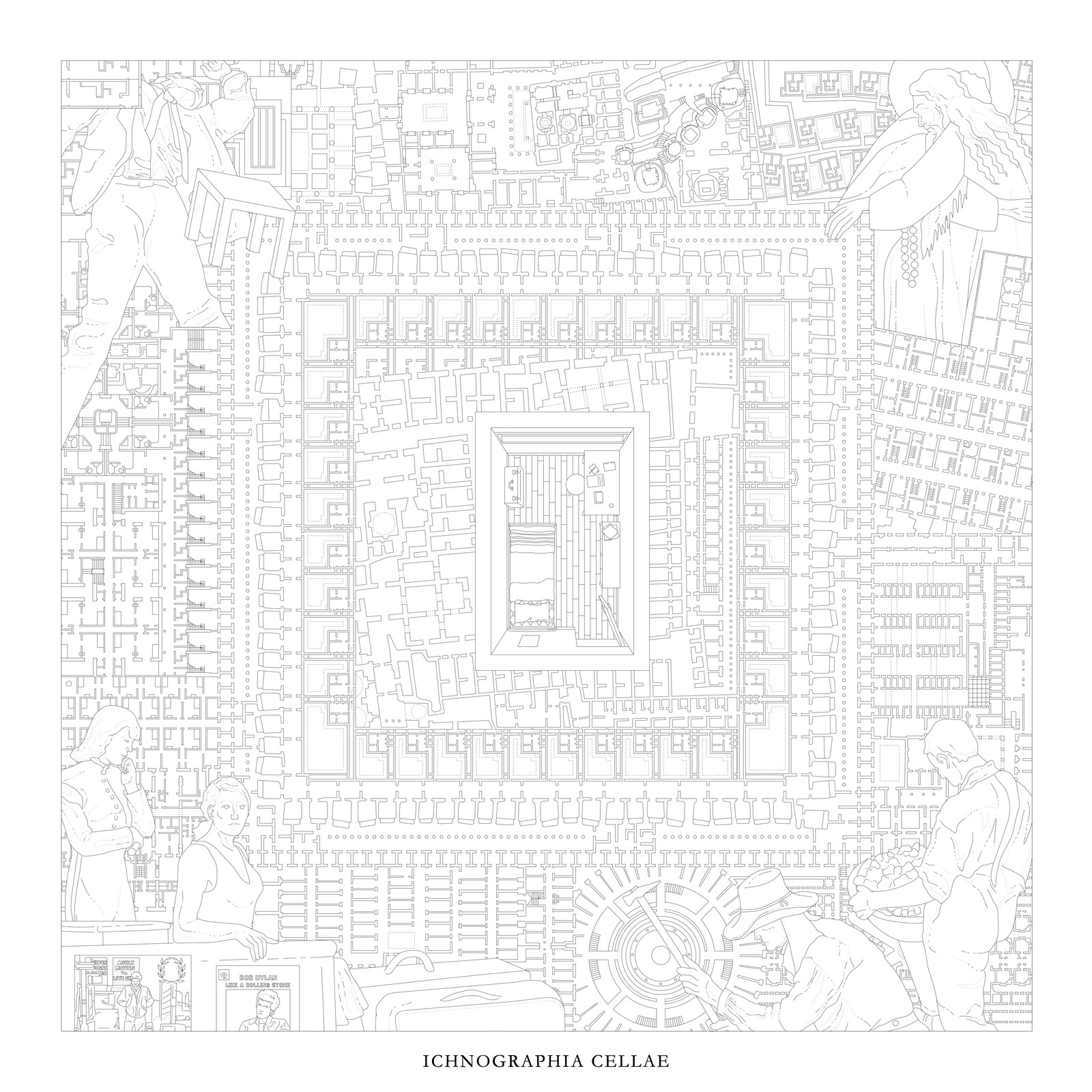

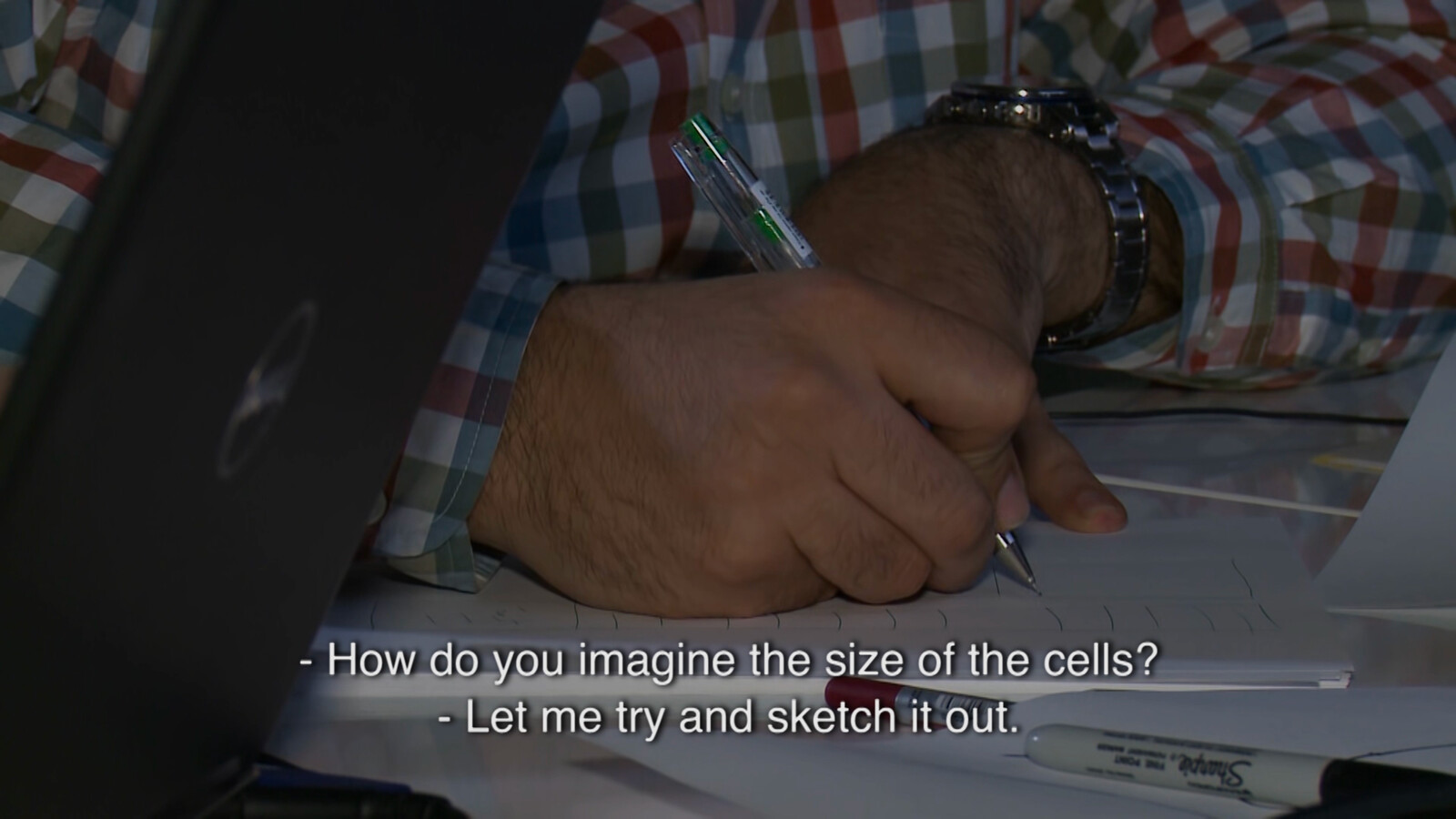

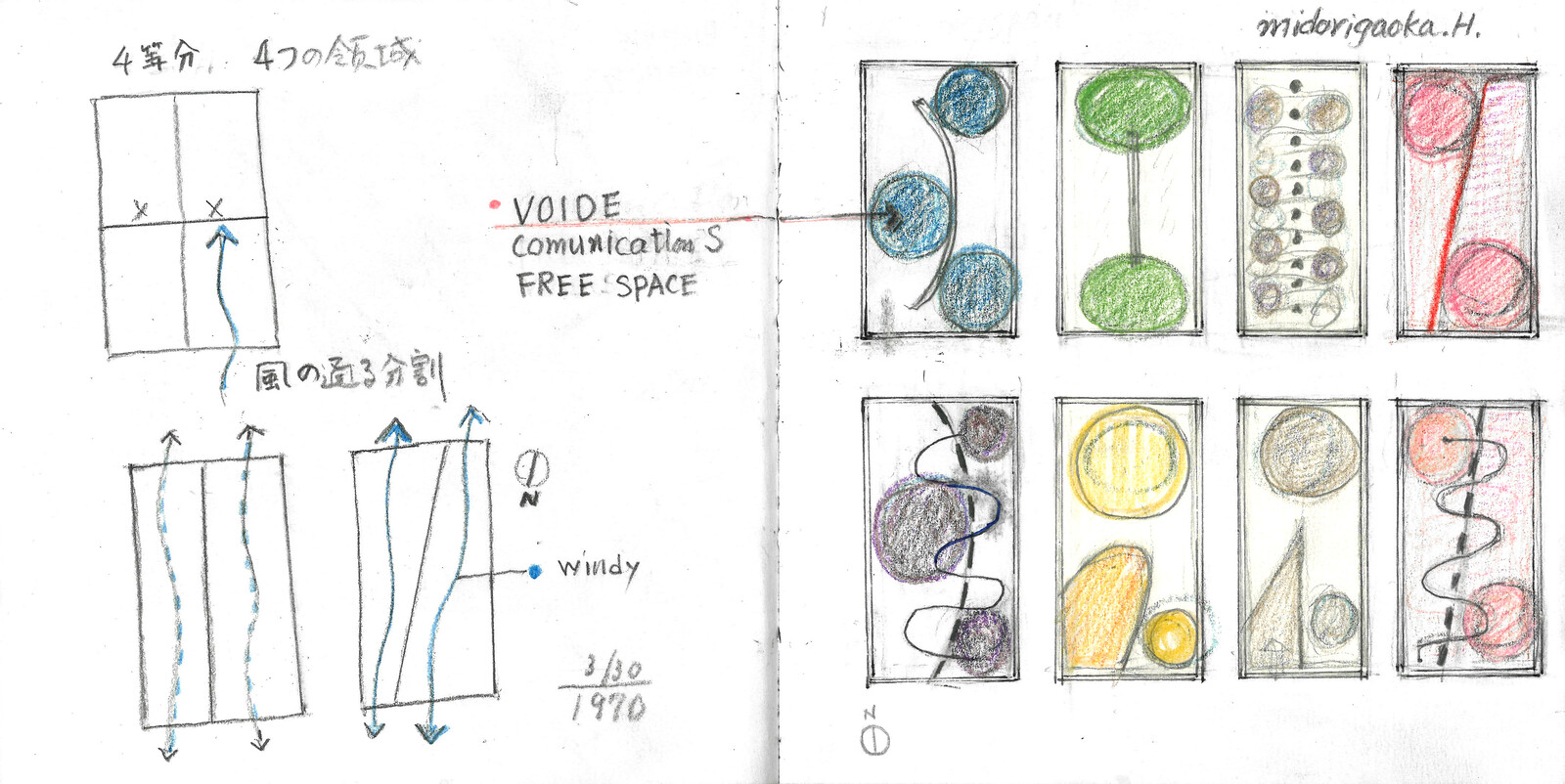

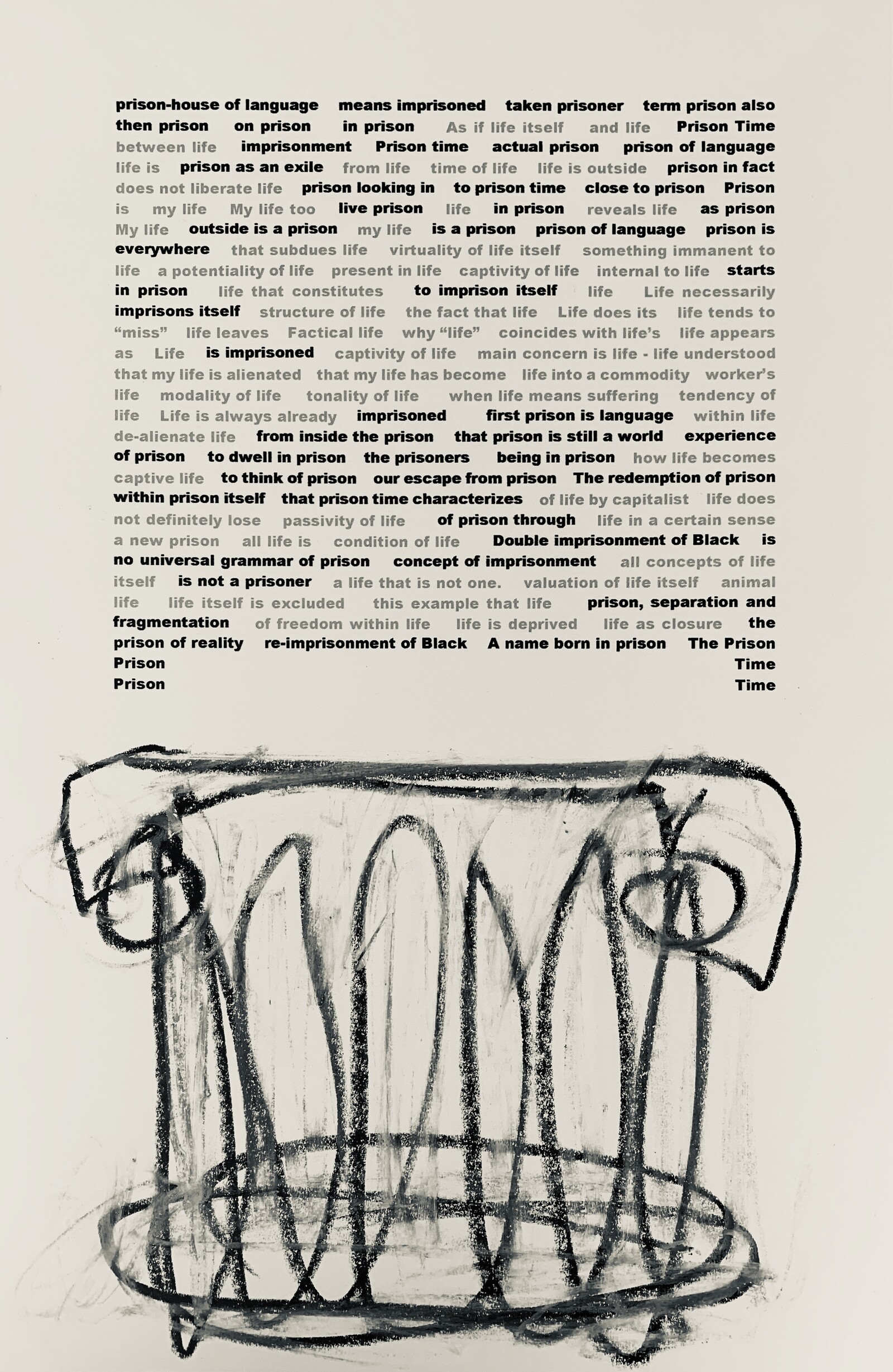

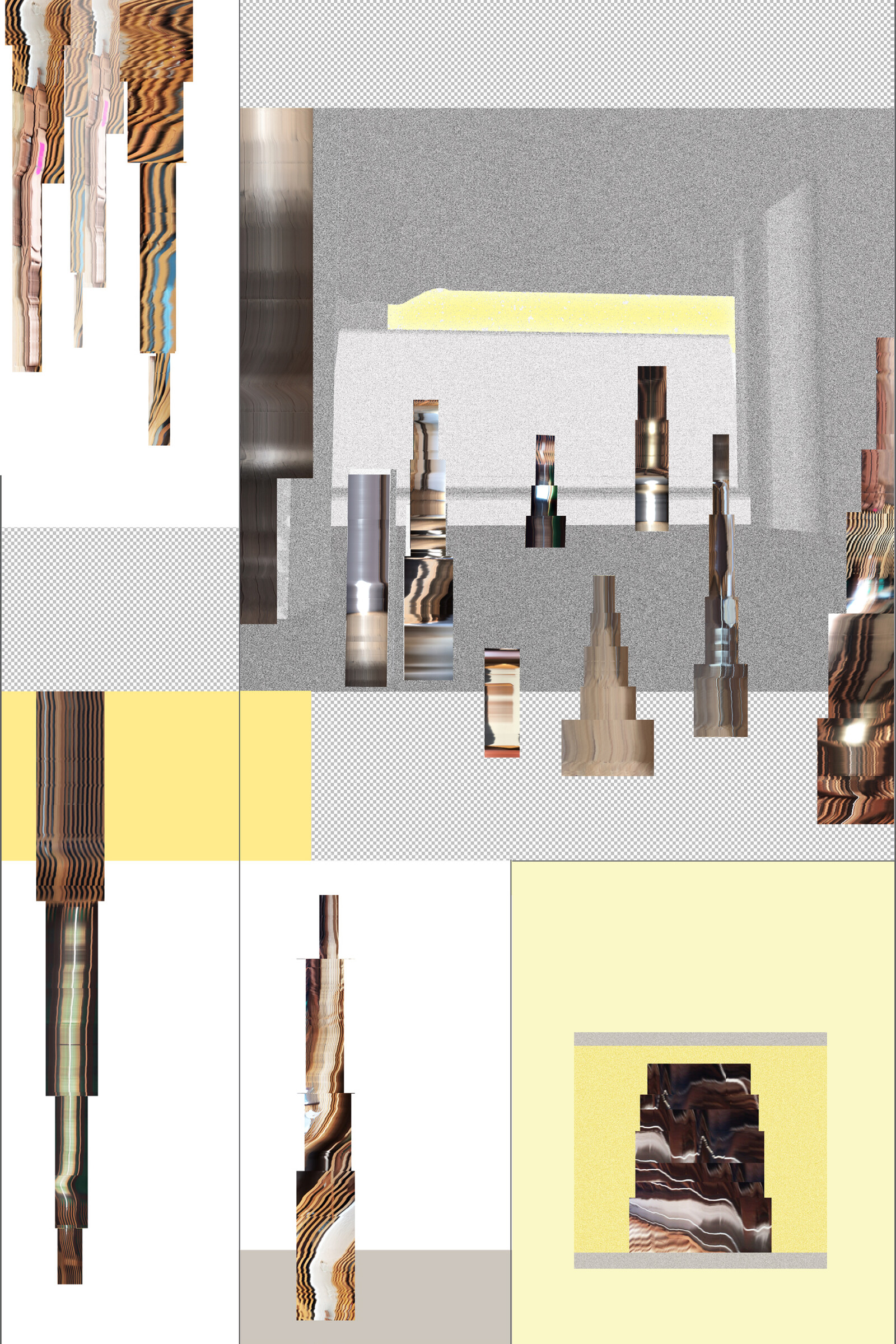

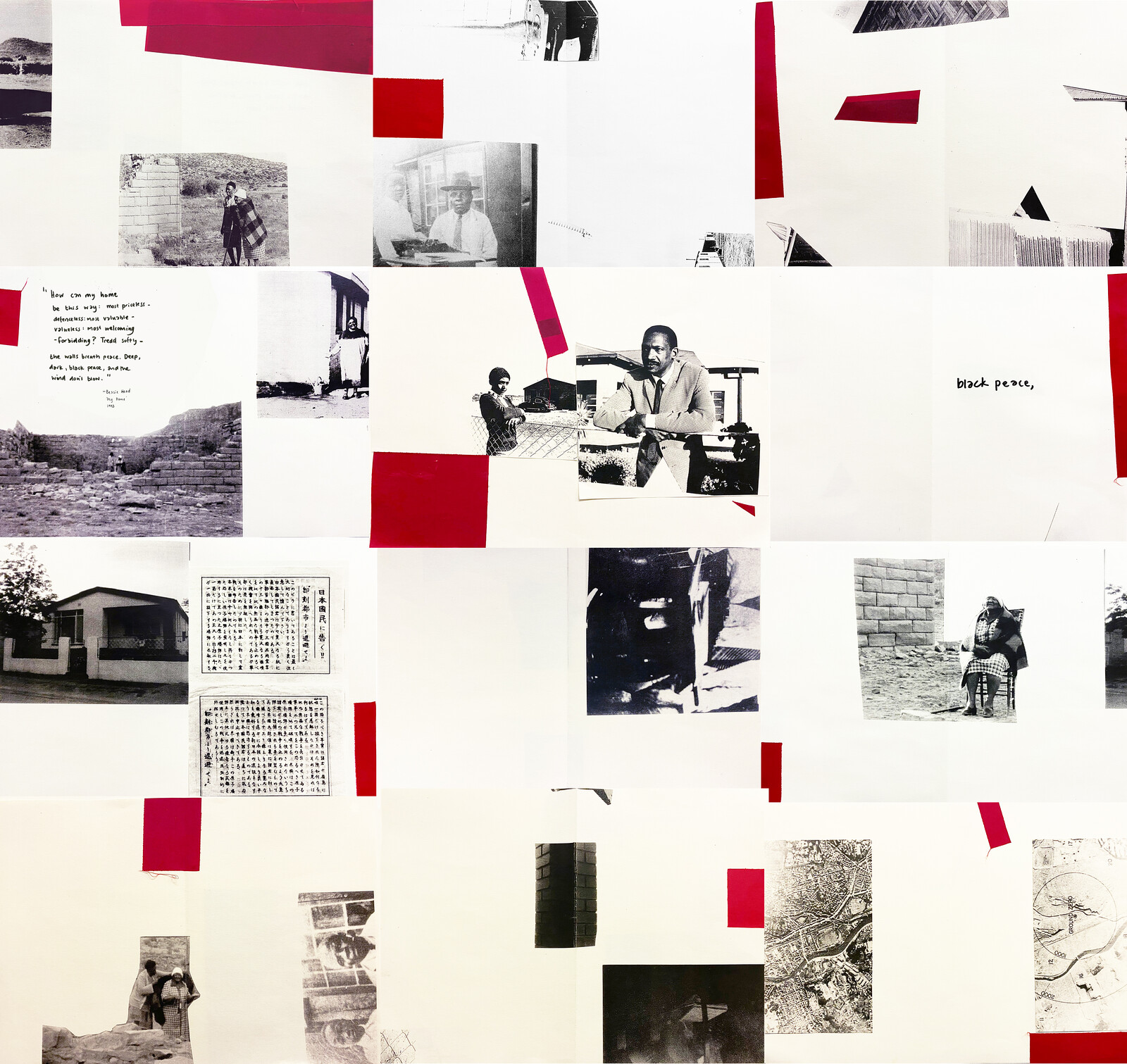

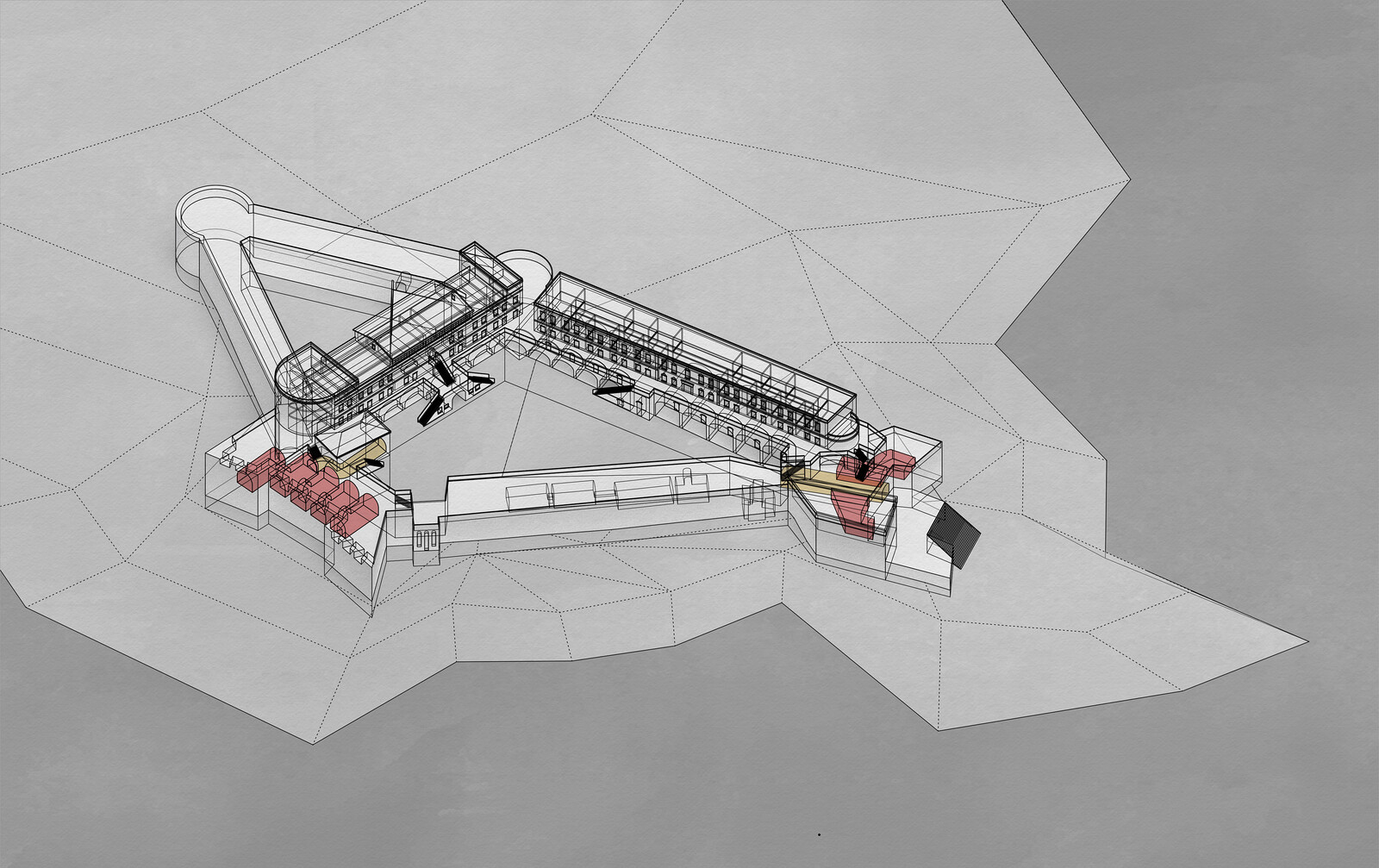

REAL, Campos, 2020.

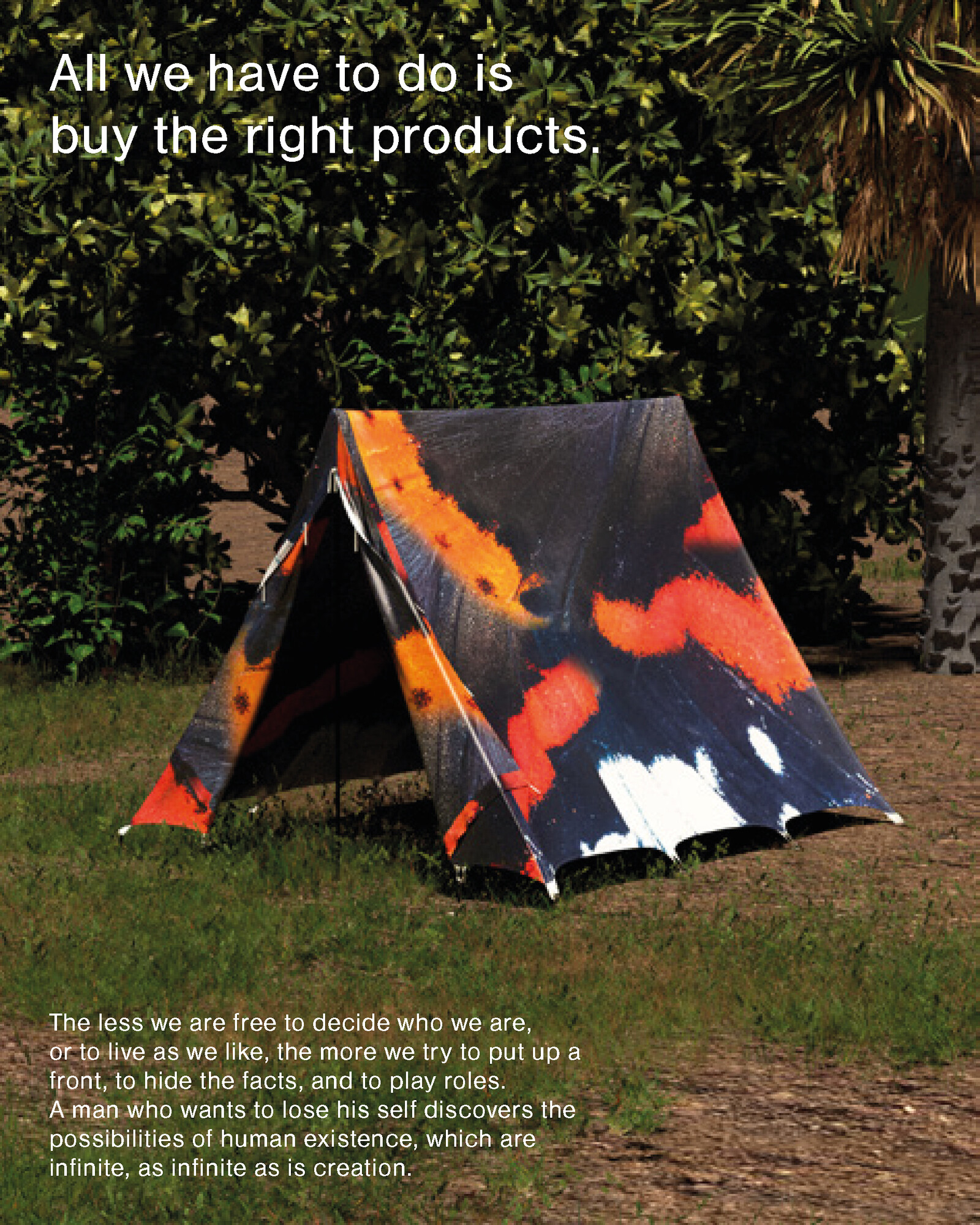

REAL, Campos, 2020.

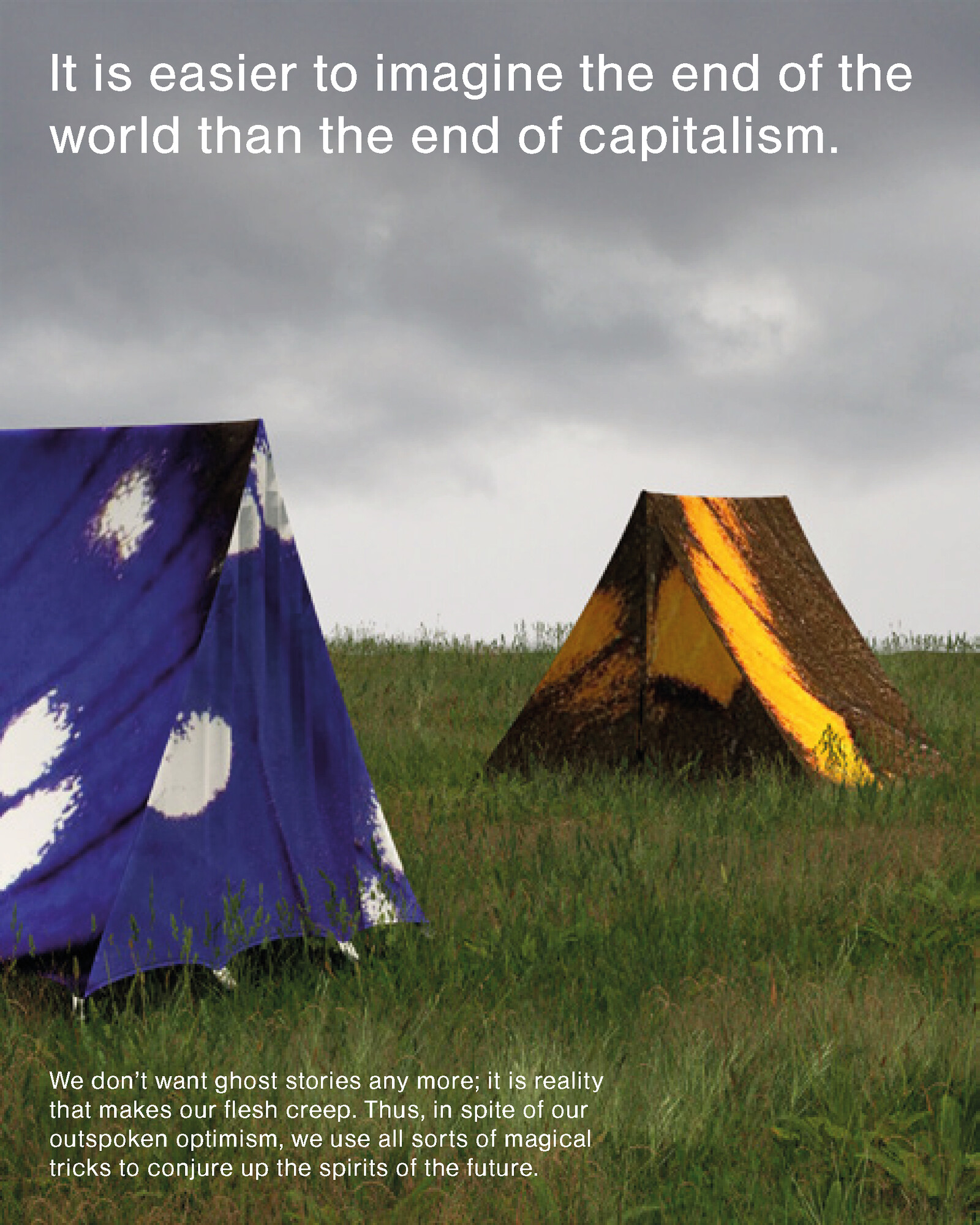

REAL, Campos, 2020.

REAL, Campos, 2020.

This might not be true, but it is an accepted myth—and not only by communists, but by the general public too. In the early twentieth century, Europe’s bourgeoisie dreamed of escaping the polluted landscapes of industrial capitalism to rediscover virgin nature. By combining the bicycle and the tent, they created recreational camping.

For at least the last 4,000 years, the tent has also been one of the most important military technologies. Without the tent, the Roman Empire would not have been possible. The Romans were the first to conceive of the tent as not only a temporary shelter but also a moveable building (and so the atomic element of mobile forts). Amongst the larger models of military tent was the pavilion, so named for its wing-like folded fabric which resembles a butterfly (or papillon). The pavilion is still associated with its late Middle Ages role as a place for neutral diplomacy.

In this sense, the tent—and by extension the pavilion—represents both the essential freedom of humanity and its terrible oppression by their own hand. The tent symbolizes both life and imprisonment. The utopian tent belongs to a species without war, without scarcity. The dystopian tent (which exists) is an instrument of violence, dispossession, and alienation.

Hannah Arendt’s text We Refugees reminds us that the legal concept of the refugee is barely eighty years old. Her words are partnered with excerpts from Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism. To give these ideas the greatest chance at being seen, they are accompanied by images of tents—each is decorated with the wing pattern of a rare or endangered British butterfly.

Confinement is a collaborative exhibition curated by gta exhibitions and e-flux Architecture, supported by the Adrian Weiss Stiftung and the ETH Zürich Foundation.