On December 7, 1927, Antonio Gramsci reached the island of Ustica after five attempts to cross the sea from Palermo. He was the fifth political prisoner landing in the island, imprisoned by the newly established fascist regime because he was the leader of the Communist party. Two weeks after his arrival, the political prisoners in Ustica became thirty. At the end, the confinement of Ustica came to accommodate about 3,000 people.

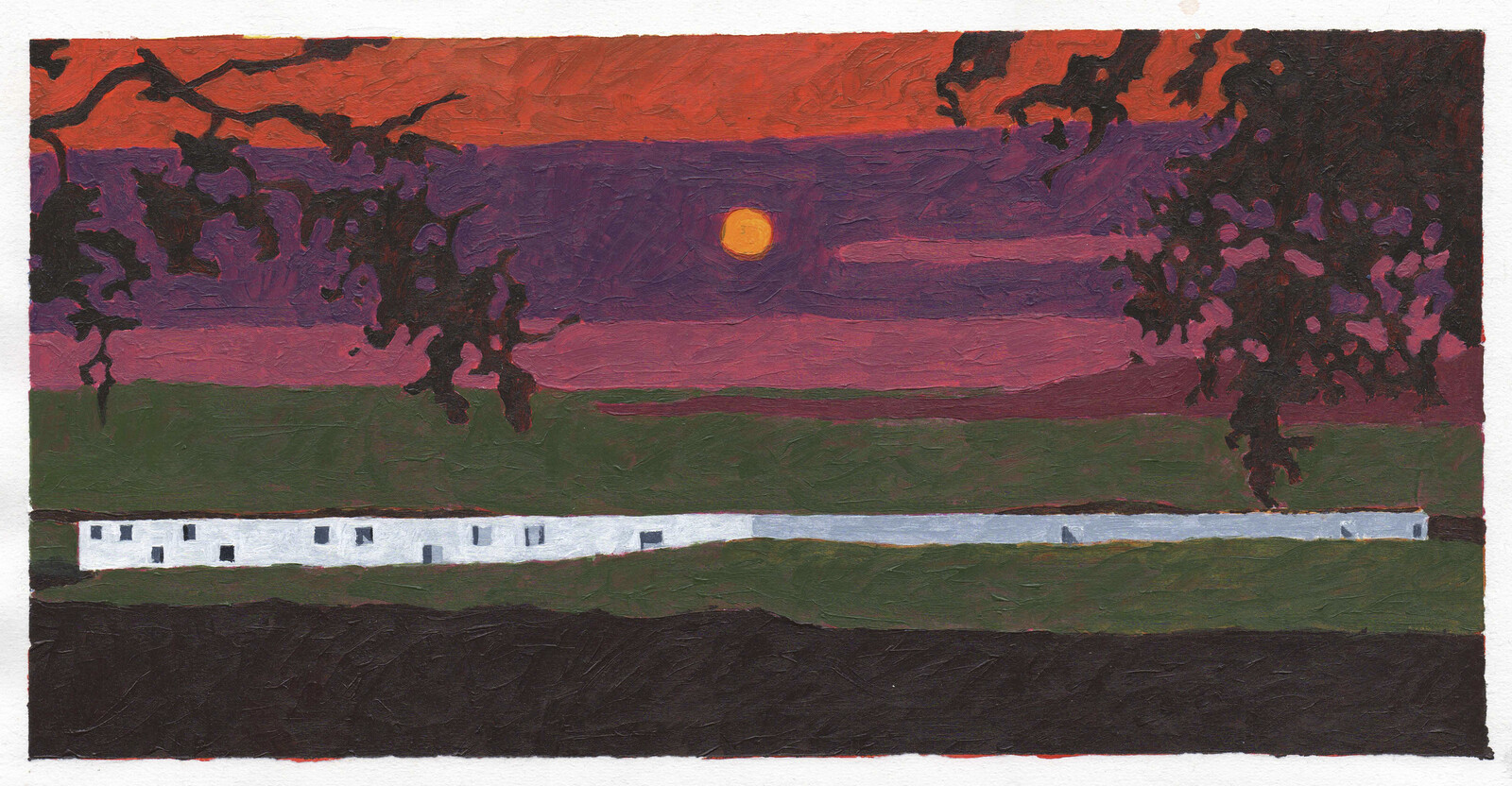

2A+P/A, The house, 2020.

Gramsci lived in a private house that he rented together with other five inmates: The house, he wrote, “consists of a room on the ground floor where they sleep two. On the ground floor there is also the kitchen, the toilet, and a closet that we have used as a toilet… On the first floor, in two rooms, we sleep in four, three in a large enough room and one in the corridor; a large terrace is over the biggest room and dominates the beach.”1

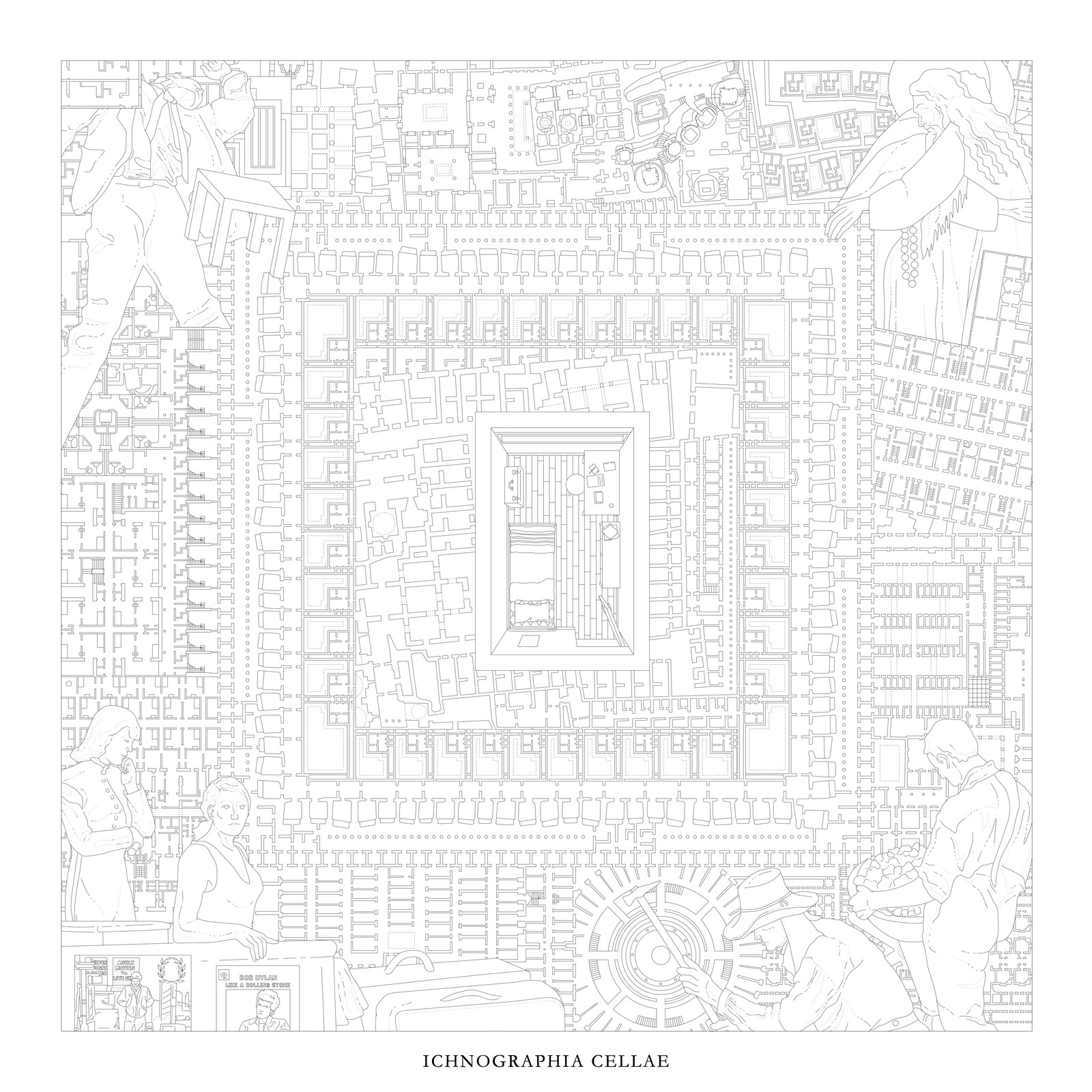

2A+P/A, The room, 2020.

The furniture in Gramsci’s small room was very basic: a bed, a cabinet, a desk over a small platform to see outside while sitting on a poor chair. It was similar to a monastic cell, but with more freedom. “The regime to which we are subject consists of: retiring home at 8pm and not leaving the house before dawn; not to go beyond the town limits without a special permit.”

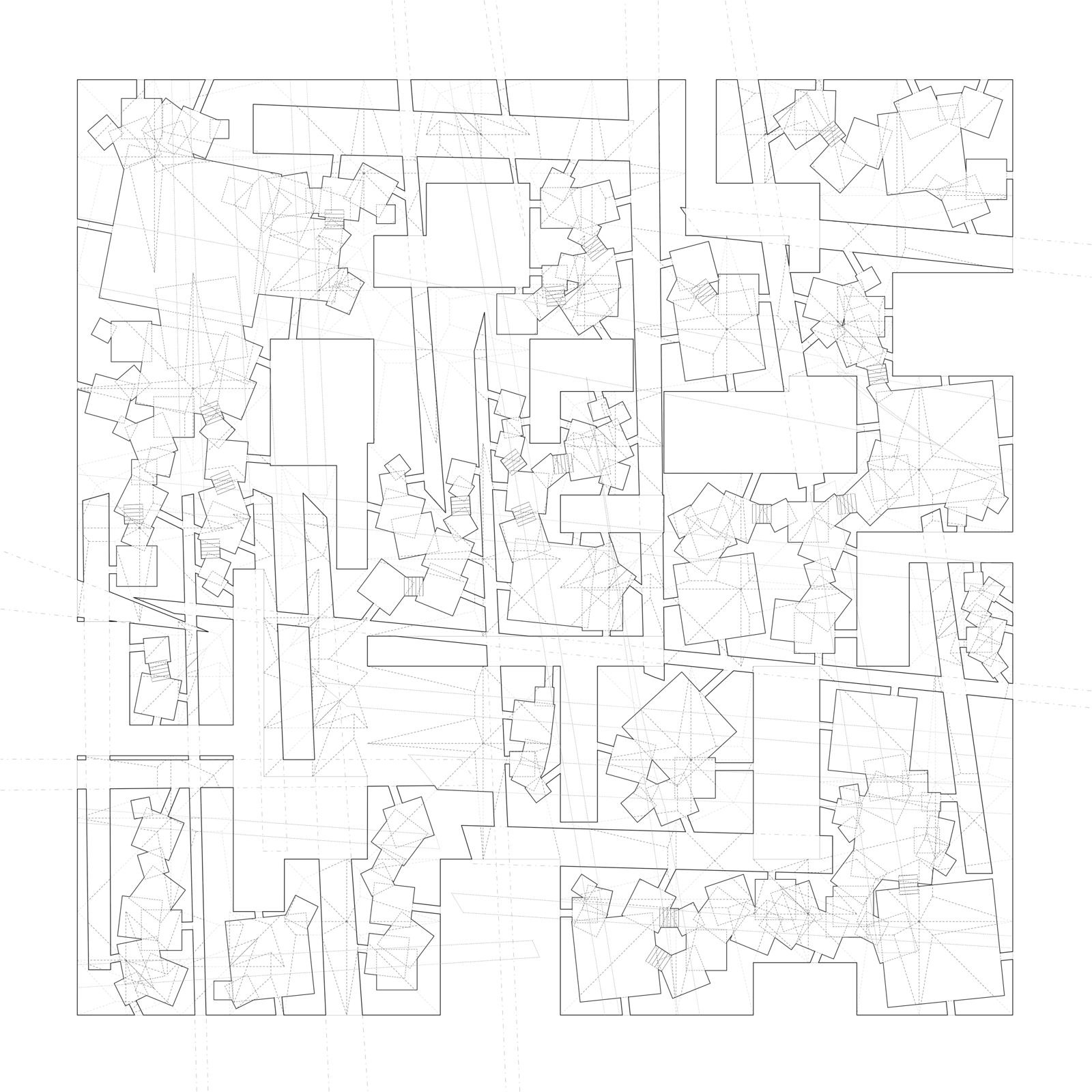

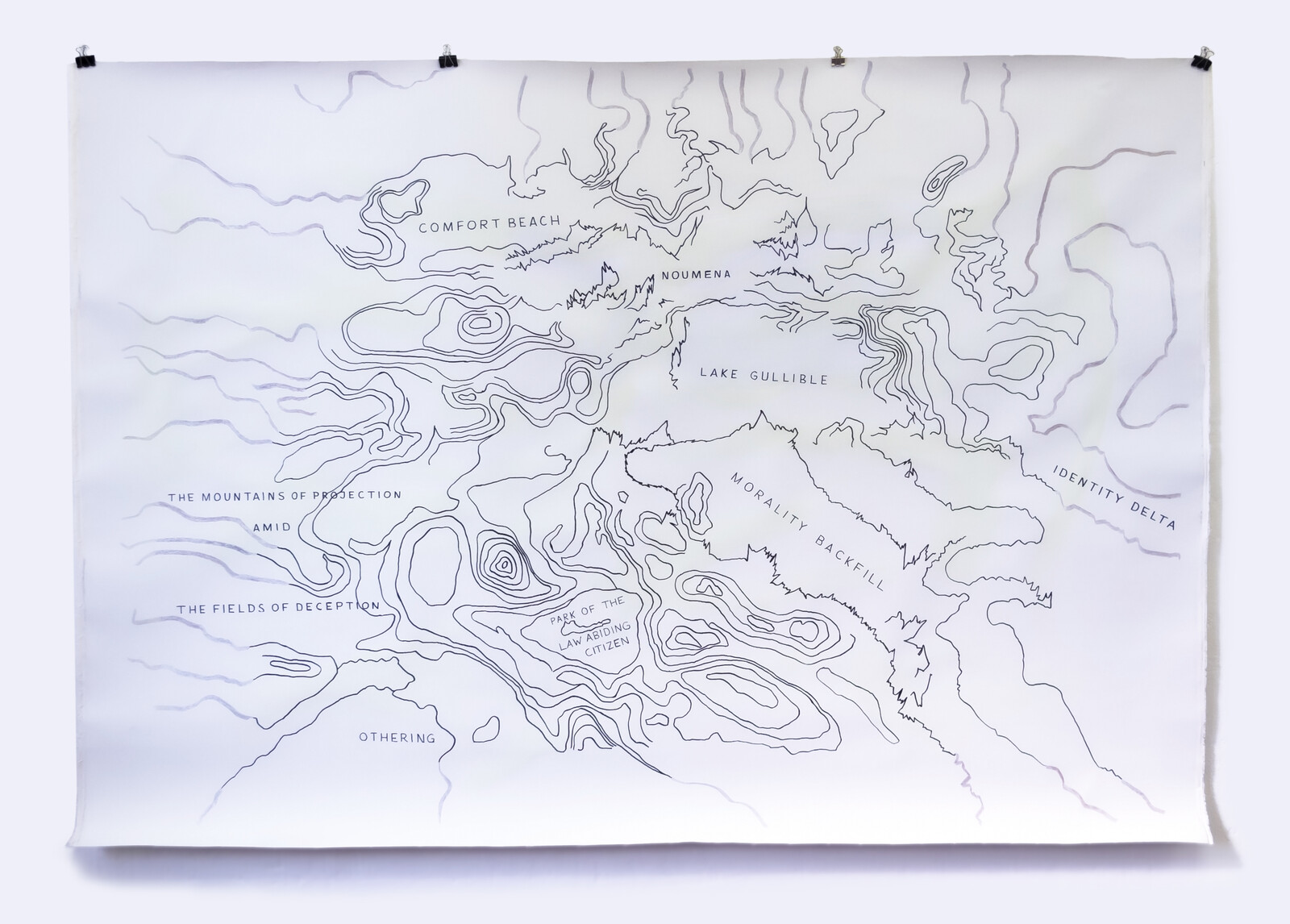

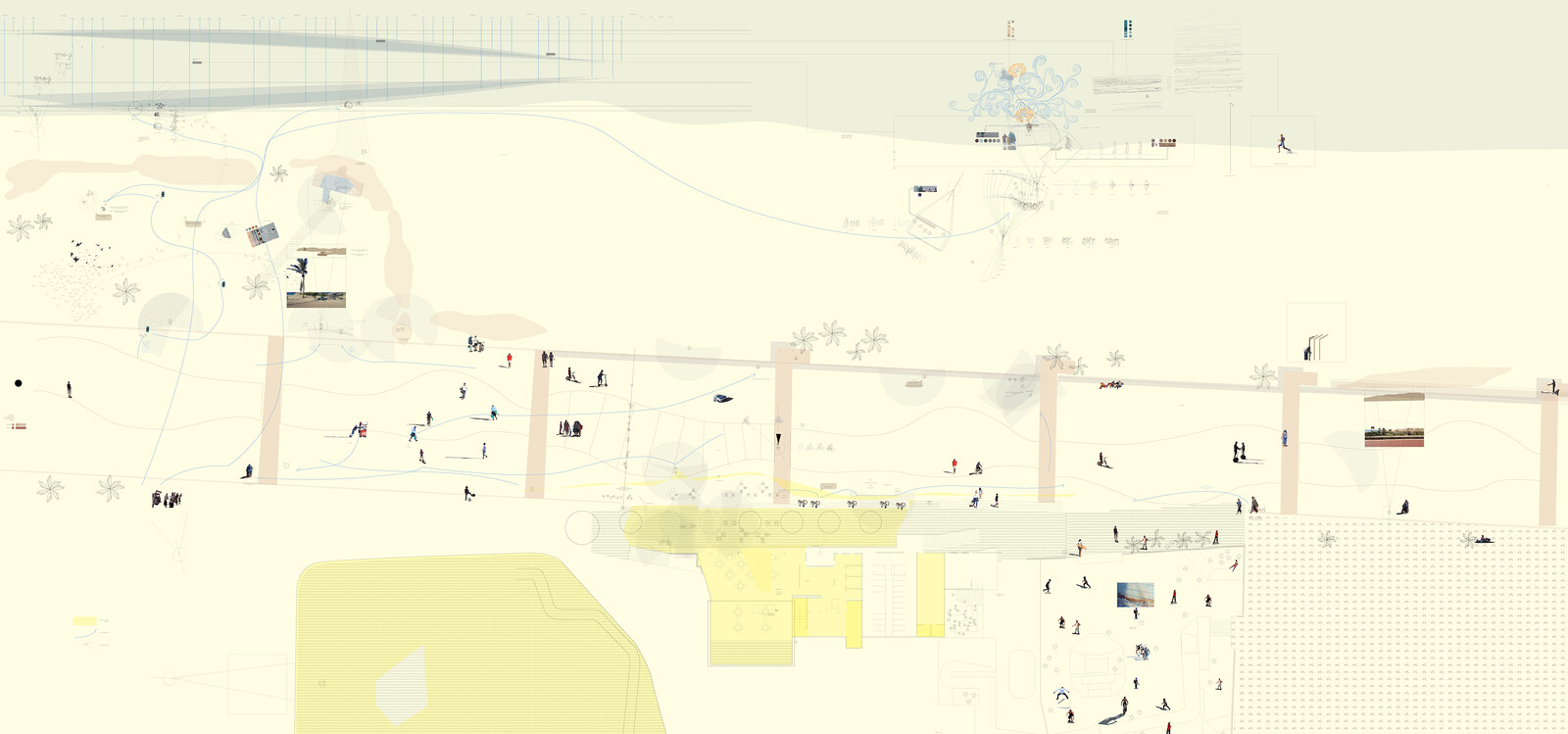

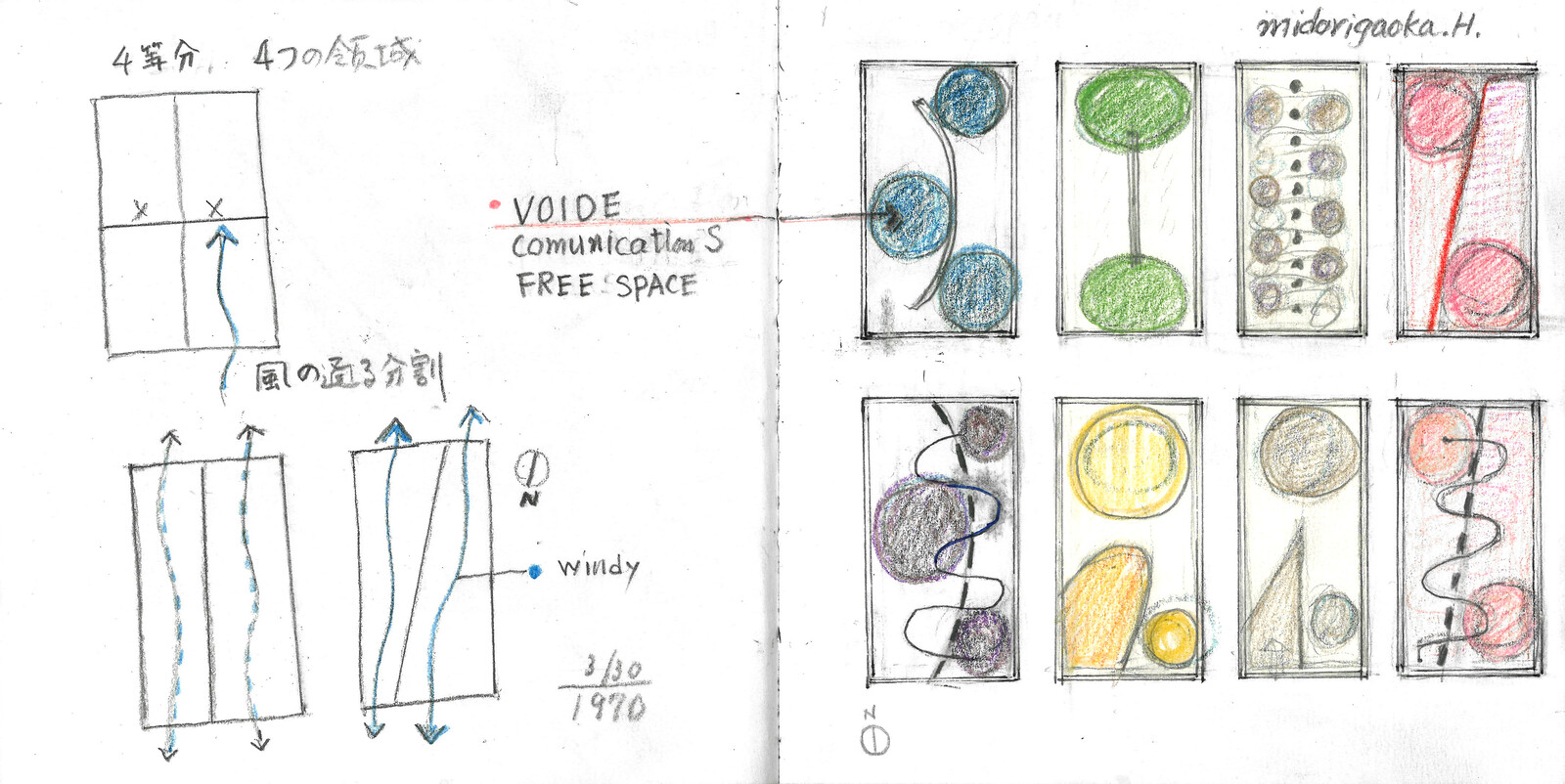

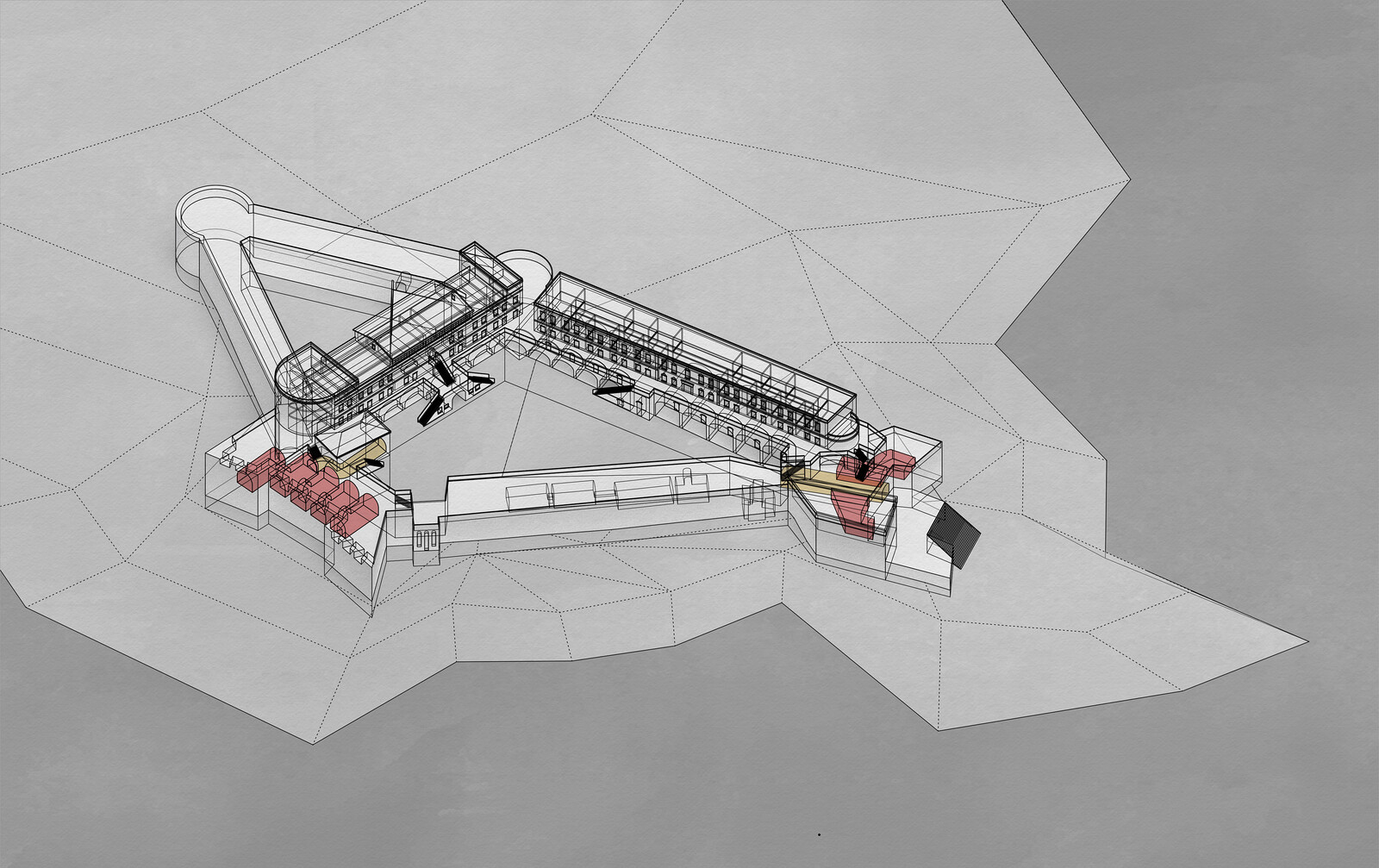

2A+P/A, The island, 2020.

From the window of his room he could see the landscape of the island. 1,600 people inhabited the island at that time; 600 were prisoners. “It is impossible to imagine the life of Ustica, the environment of Ustica, because it is absolutely exceptional, is out of every normal experience of human coexistence.”

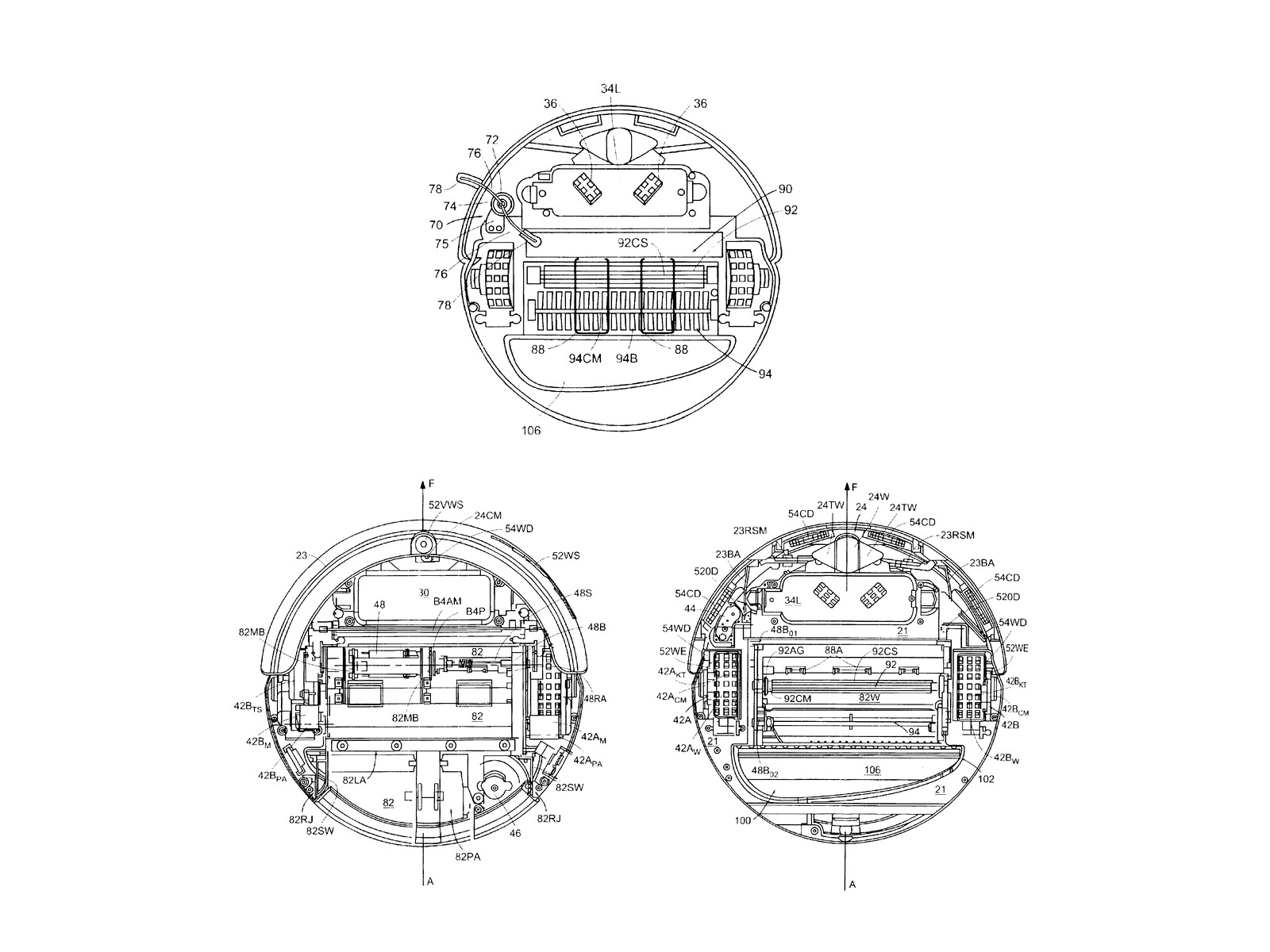

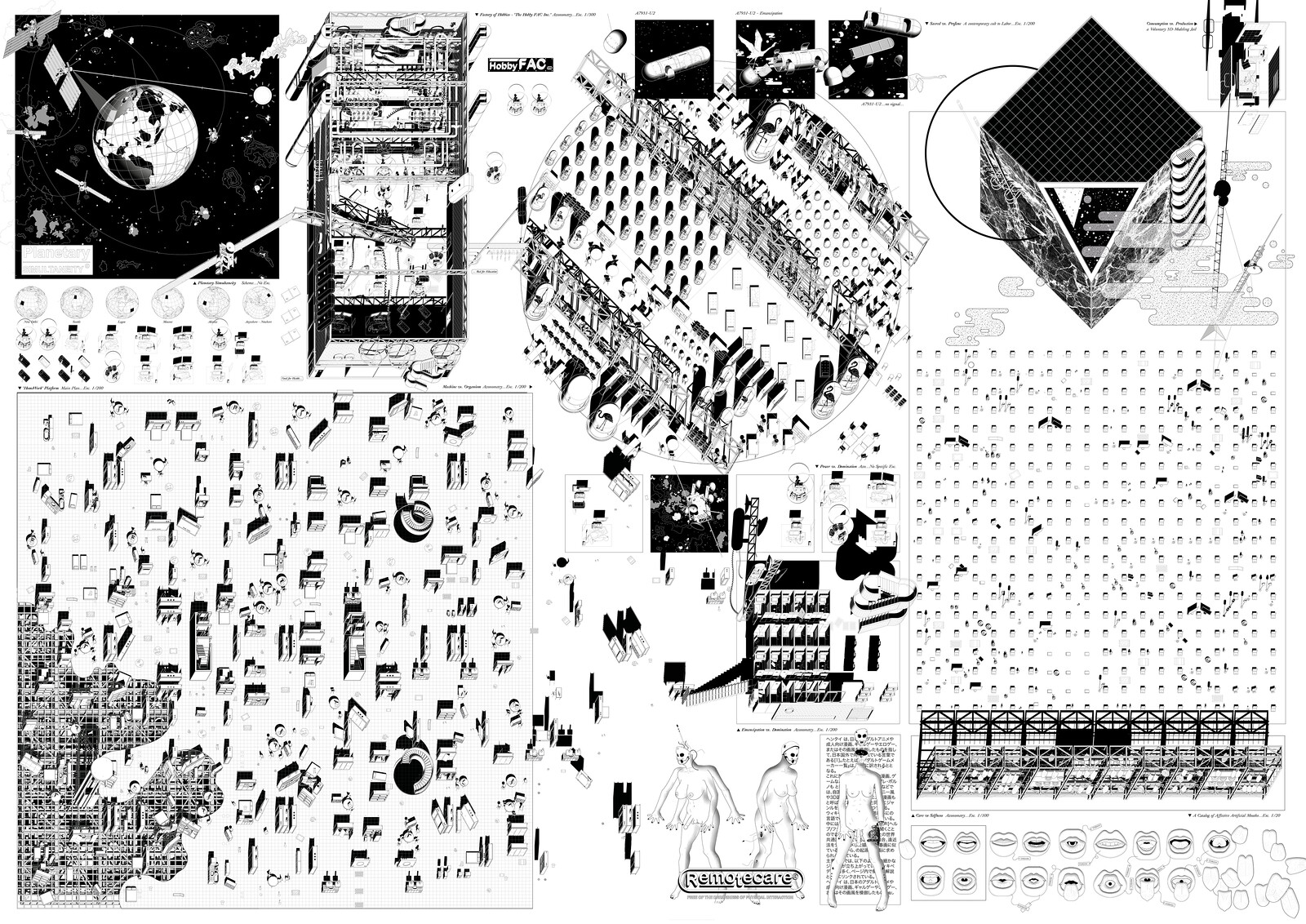

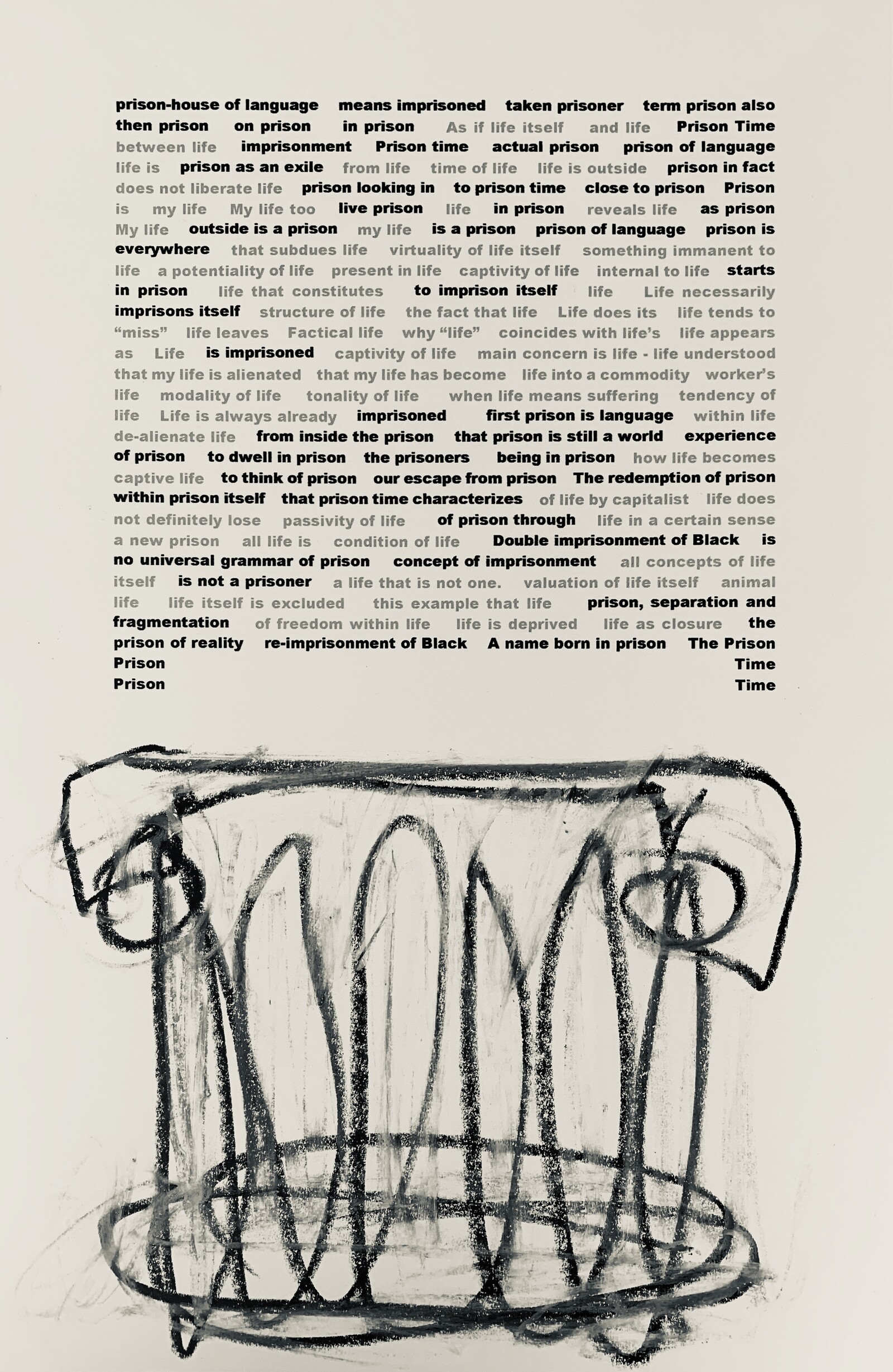

2A+P/A, The books, 2020.

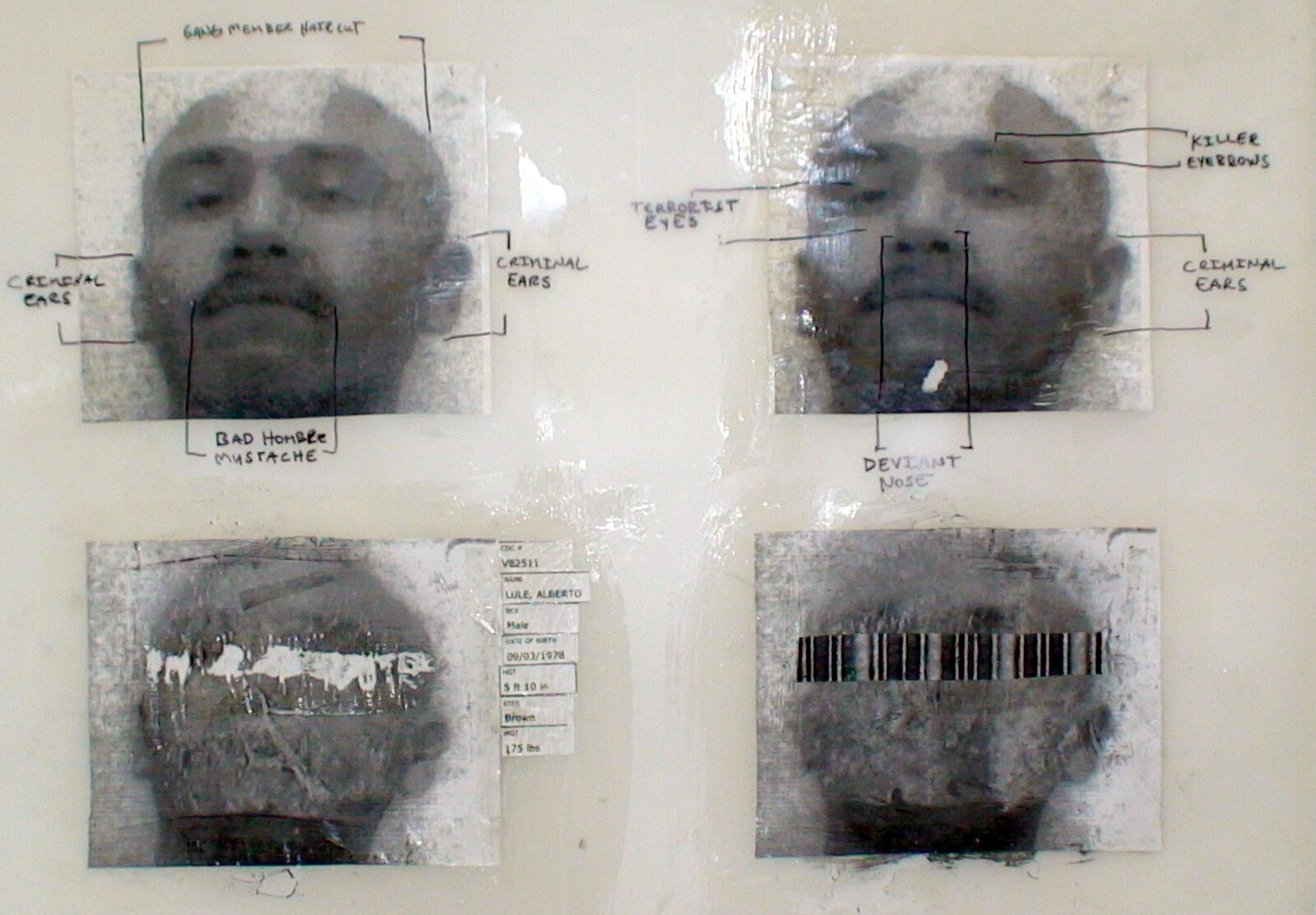

“This is a monstrous machine that crushes and levels. Sure I’ll resist.” Since the beginning of the imprisonment Gramsci understood that he would have to struggle to keep his dignity. His testament to this are the famous Quaderni dal carcere (Prison Notebooks)—a series of essays collected in about 3,000 pages of history, philosophy, and economic and social analysis.

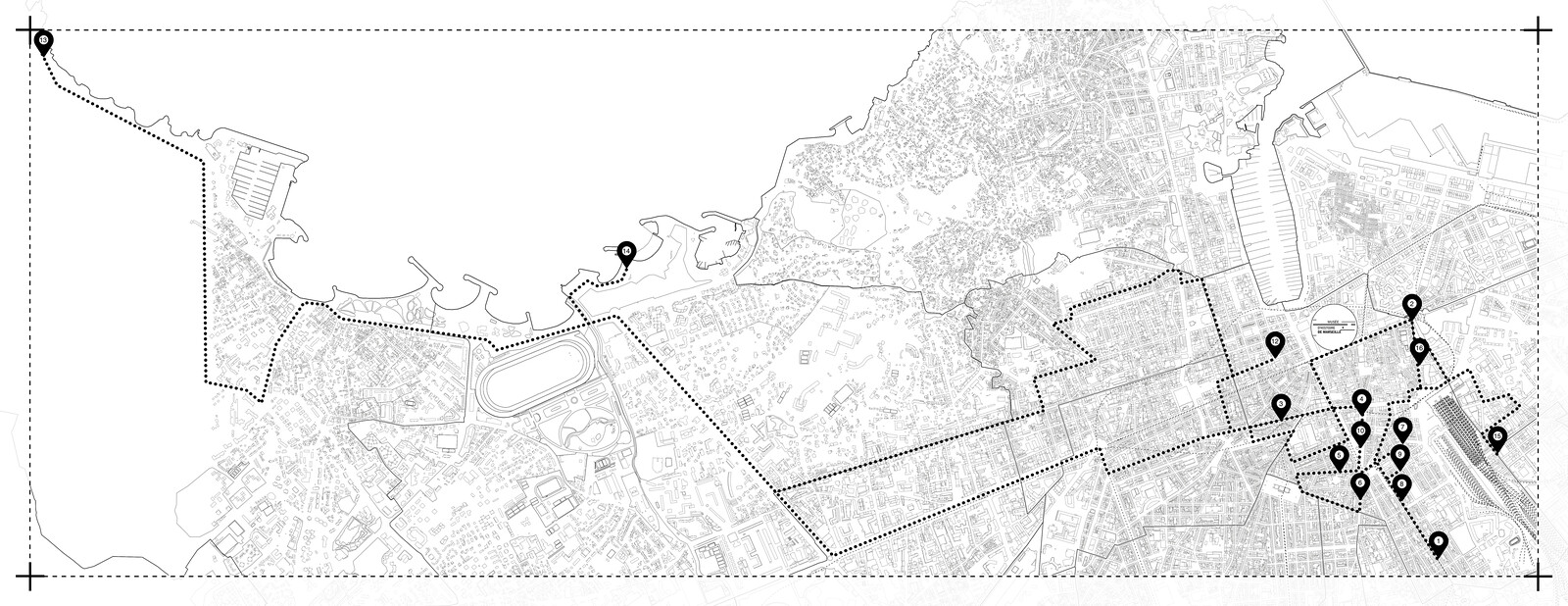

2A+P/A, The school, 2020.

The prisoners decided to start a school to share their different knowledges. “We have already started a whole series of courses, elementary and general culture, for the different groups of confined… We thus hope to pass the time without being brutalized and helping the other friends, who represent the whole range of parties and cultural preparation.”

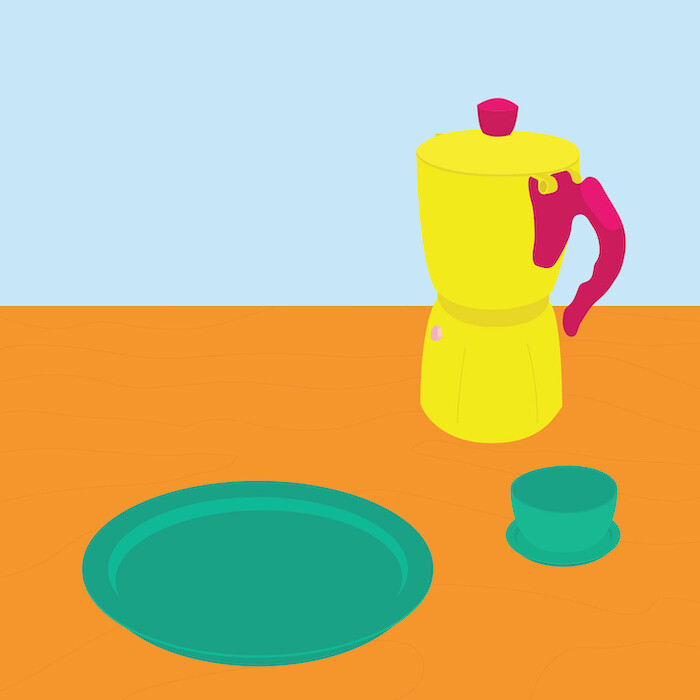

2A+P/A, Hot coffee, 2020.

A hot cup of coffee was the morning ritual, the first act of an infinite routine. “In the morning, I am usually the first to get up; the engineer Bordiga states that at this moment my step has special characteristics, it is the step of the man who has not yet taken the coffee and is waiting for it with a certain impatience. I myself make coffee.”

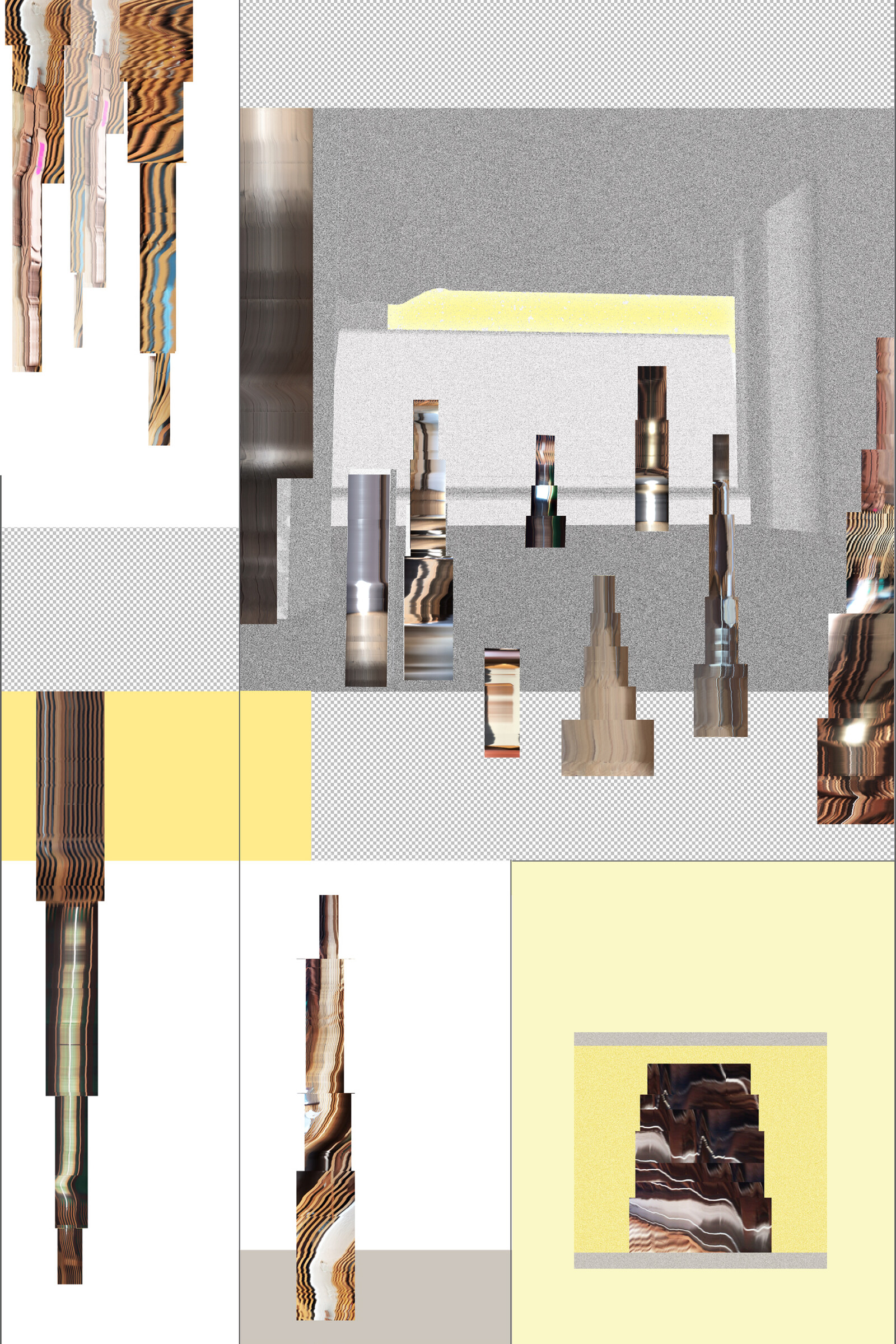

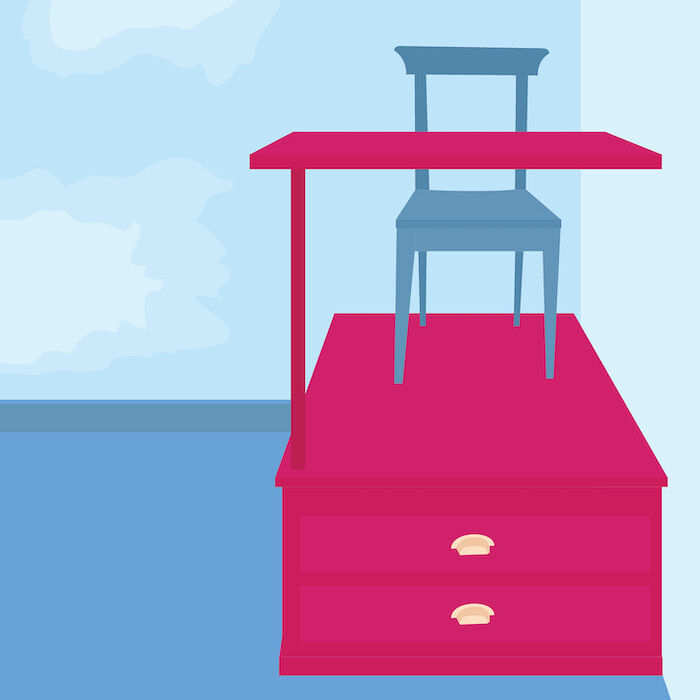

2A+P/A, Desk, 2020.

The epistolary contact with friends and family was crucial. It was his way to keep a sense of reality beyond the borders of isolation. “When I have no argument for a letter, and for me this is the most common case, I will send you at least one postcard, so as not to miss any postal travel: life goes by here monotonous, uniform, without jumps.”

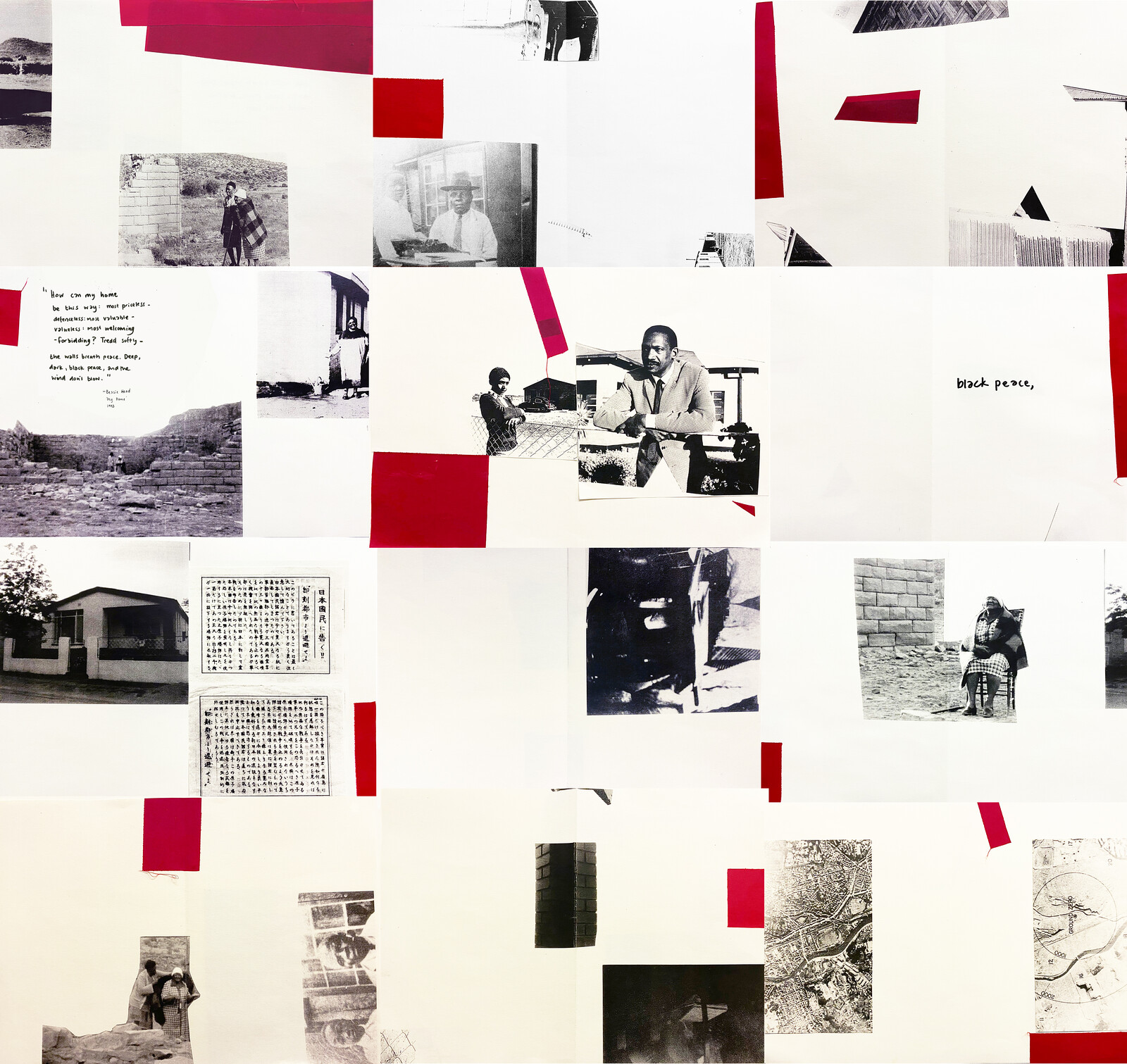

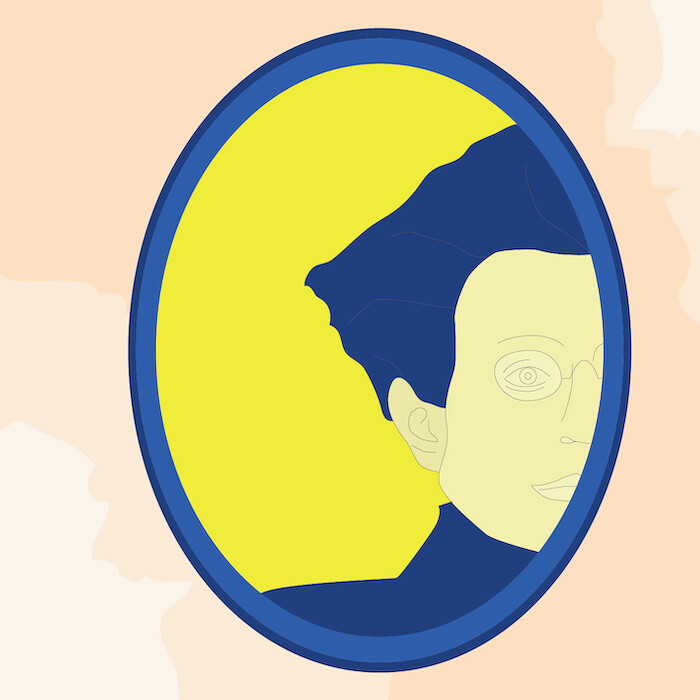

2A+P/A, The man, 2020.

Isolation brought Gramsci towards an intellectual and physical struggle that he fought with simple weapons: books, newspapers, and his didactic activities as teacher and scholar. His story, magnificently recorded in his writings, is a precious legacy, one that is capable, even today, of making us reflect on the ethical and moral value of our ideas.

All quotes come from the book Lettere dal Carcere (Letters from the prison), which collects all the mails that Antonio Gramsci sent to friends and family during the years he passed in prison, published by Einauidi in 1947. Antonio Gramsci, Lettere dal carcere, eds. Palmiro Togliatti and Felice Platone (Torino: Einaudi, 1947).

Confinement is a collaborative exhibition curated by gta exhibitions and e-flux Architecture, supported by the Adrian Weiss Stiftung and the ETH Zürich Foundation.