We are outfitted with senses that convey the surfaces of things…our ways of probing the viscera of the world is to turn them into yet more surfaces.

—Lorraine Daston1

1. Prison Caves

Herman Melville’s 1856 short story The Piazza reverses Plato’s cave metaphor of prisoners and their illusions.2 Platonic elements of light, darkness, and shadow no longer signify truth, ignorance, and illusion; instead, knowledge, distance, and vision are entangled.3 It is a story about the peril of admiring the natural world from afar: perceiving it through frames, reflections, and surfaces. A lonely narrator speaks of his newly-found solace in mountain views; he admires them from his home’s outdoor piazza. One day he sets out to discover a glowing spot that he noticed far away in the mountains. Along his way, he finds a house where a woman named Marianna lives alone. She spends her days looking at shadows; projections of natural phenomena coming through her windows—clouds, a tree, a rock—which she imagines as creatures who become her companions. She perceives these phenomena without looking outside. Sunlight coming from the window blinds her vision.

When the story’s protagonist falls ill and thus becomes confined indoors, he finally manages to look closer and clearly into things. The transition from outside to inside helps him to develop a vision of truthful forms, and not idealized ones. Interiority here relates to the pursuit of knowledge: darkness and staying inside can reveal truth while venturing outside produces illusions.

In the parable of Plato’s cave, the prisoner’s knowledge—or the origin of forms—is produced by an artificial source—fire—and not by the sun. For Plato, it is the artificiality of the light source that produces illusions. In Melville’s story, however, this is reversed: it is sunlight that induces illusions and darkness that reveals the truth.4 At the story’s end, having traveled and confronted the real, the narrator prefers to retreat into his artificially lit “stage,” his piazza. In his words, he prefers “to stay with the illusion.” The narrator’s piazza and Marianna’s windows are frames which flatten landscapes and phenomena onto surfaces. A primordial interior, the cave can either reveal or obscure truth.

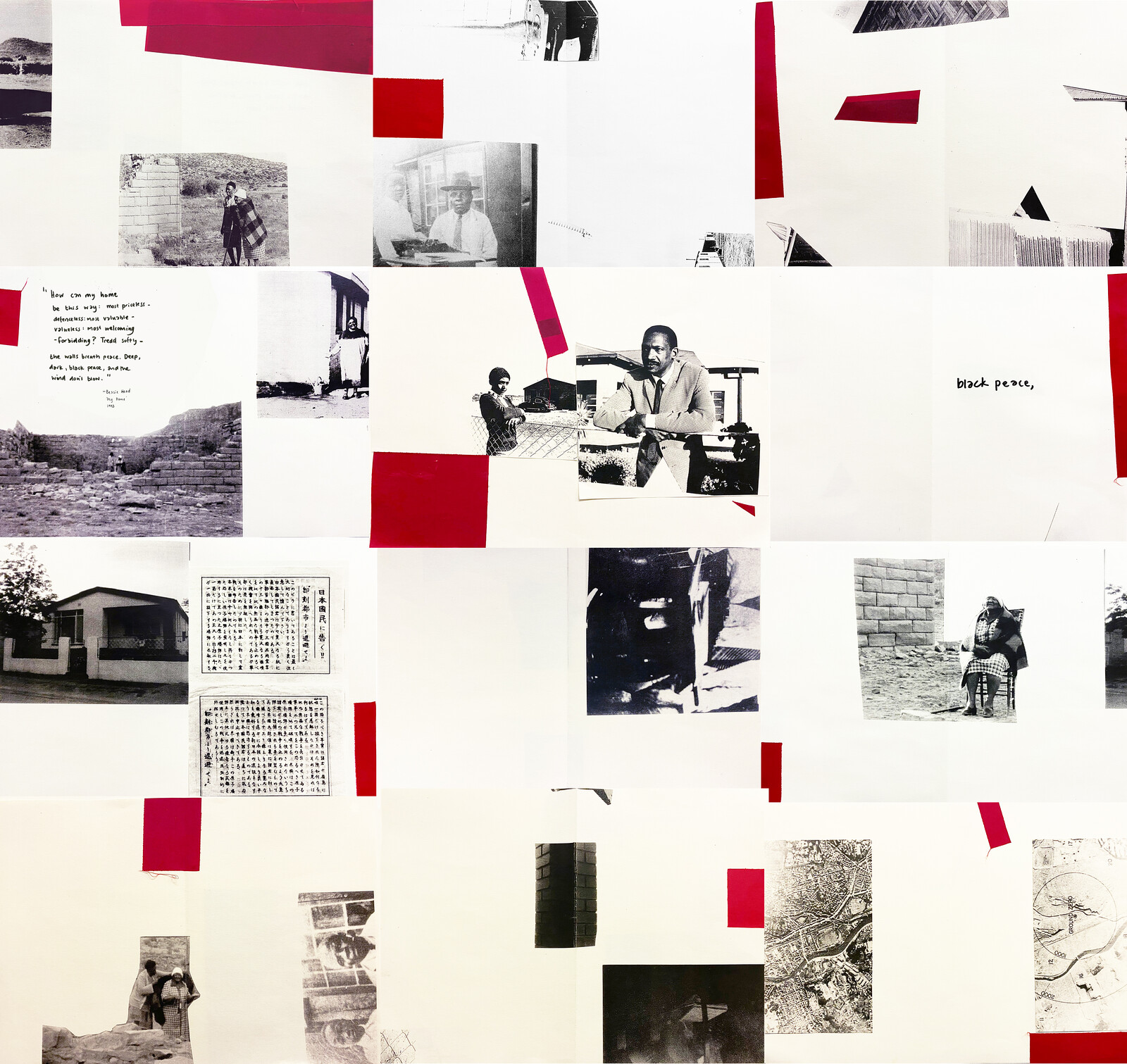

2. Cave Communities

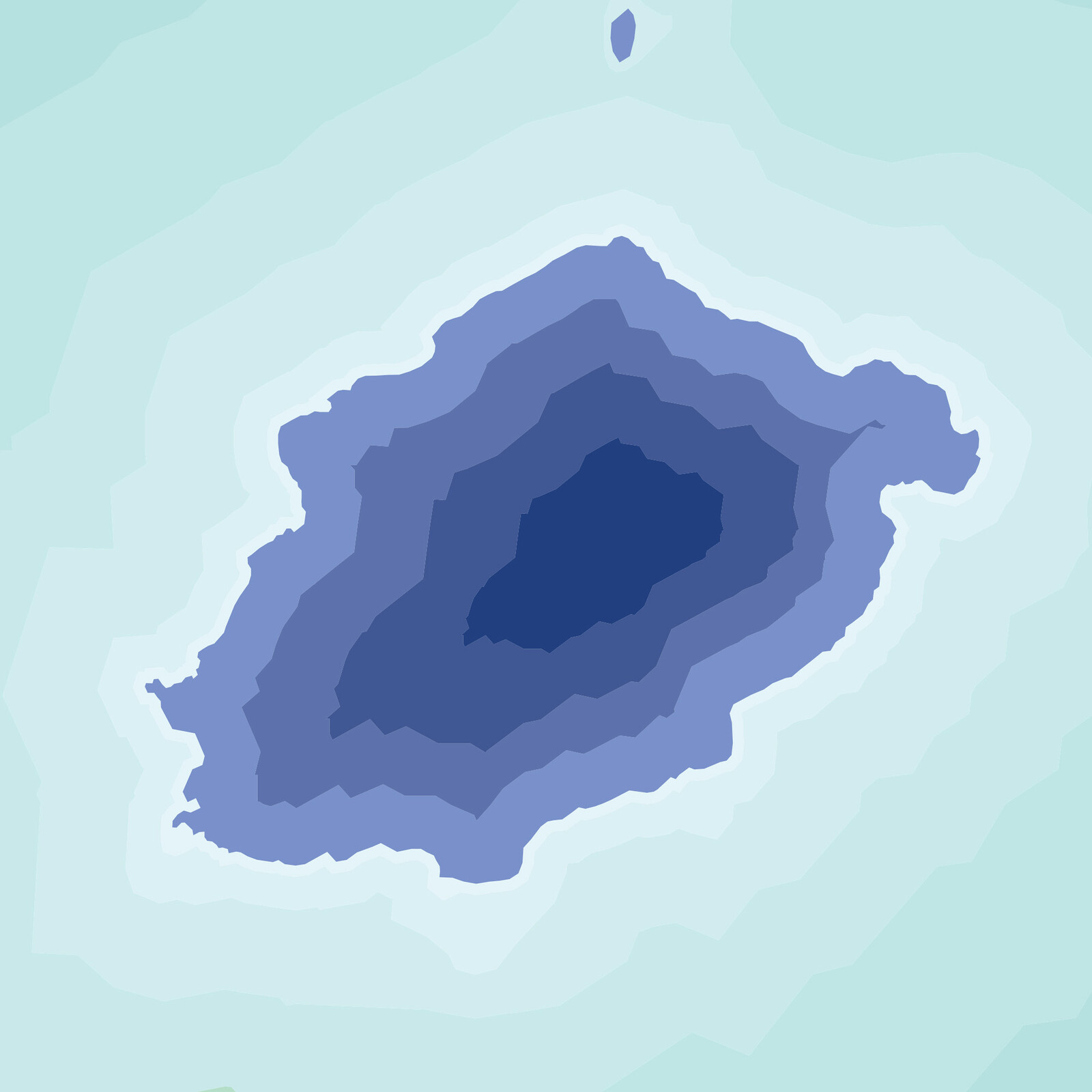

What is striking about caves is their static nature. Once cave-forming processes have ended, their environments might not change for thousands or potentially millions of years.5 For a cave to be formed, a rock type is needed that can dissolve in water. Caves are usually formed by limestone being dissolved by a mixture of carbon dioxide and rainwater. Characterized by a weak acidic chemical consistency, once the water meets the soil, it seeps into the cracks of subterranean rocks. As the rock dissolves, fractures are carved out, which form caves.6 Cave interiors are a result of external environmental chemical processes. Their interiority is conditional upon their contact with the outside.

Cave environments have a unique community ecology. “Biocoenosis,” a term coined by Karl Möbius in 1877, defines an assemblage of different species living in a particular space and time. There are many members of the cave community.7 Troglobionts have adapted to cave life with slow metabolism and a loss of eyesight. They cannot survive in over-ground, non-hypogean habitats, so troglobionts are often endemic to one specific cave. Trogloxenes are guests who frequent caves for their shelter and favorable microclimate, but return periodically to the surface for food. Troglophiles are common inhabitants of caves but can also be found elsewhere in similar over-ground environments with cool, sheltered, and moist conditions.8

As one enters a cave and moves deeper into its interior, the abundance and the diversity of organisms progressively decreases. The twilight zone, which is the cave’s entrance is a potential site for food, and thus dense with fauna. Meanwhile the energy-deprived deep interior is poorly populated. The biocoenosis of the twilight zone is characterized by species who cannot adapt to the dark, subterranean nature of the cave interior. “In contrast, true troglobionts dominate the deep subterranean domain, where strong selective pressures promote a highly specialized community and, at the same time, limit diversity and abundance.”9

Caves are good habitats for bats. Wuhan-based virologist Shi Zhengli has explored numerous caves throughout China, taking samples from their bat colonies. From these she has identified dozens of deadly SARS-like viruses. Viruses that start from bats in caves reach us through the trade of wildlife animals in wet markets and due to the human’s encroachment of non-human habitats.10

Researchers in Zhengli’s team quickly soon found out that Covid-19 in bats was ephemeral. Her research method, Polymerase chain reaction (PCR), can quickly copy billions of DNA samples. The virus was then cultivated in a petri dish, where it interacted with lung cells. From cave, to bat, to pangolin, to humans, to the world: the shallow surface of the petri dish produces the knowledge of a deep imminent disaster.

3. Cave Breathing

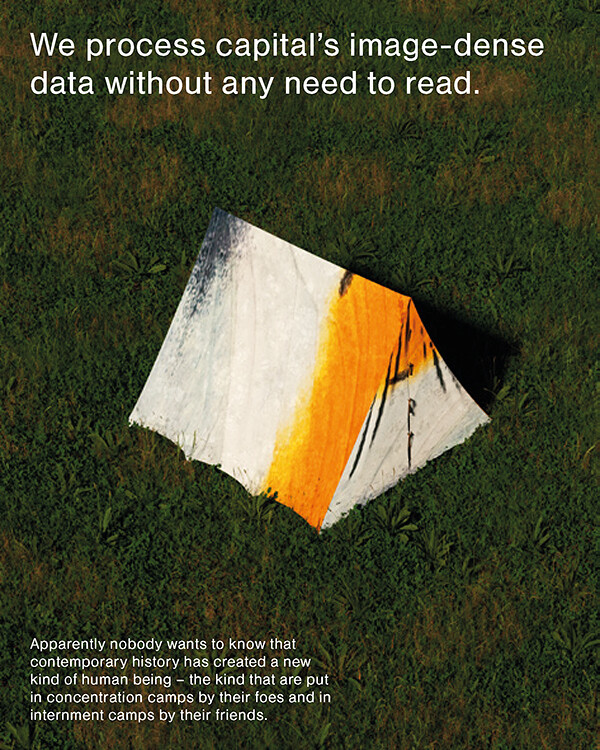

In antiquity, speleotherapy referred to the use of underground mineral and hot water springs. This underground balneo- and hydrotherapy was well documented by Hippocrates in his treatise Air, Water, and Places. There, he writes about respiratory remedies practiced by the ancient Greeks such as the inhalation of steam from salt water. Caves continued to be sites for healing in Roman times and throughout the medieval period, particularly for the breathing ailments of miners. In caves, a special microclimate prevails: their atmosphere is saturated with water vapor and is free of any suspended particles, whether mineral, organic compounds, or biological materials (e.g. pollen). Among other things, their environment is characterized by the absence of ozone, radioactive particles, and acid reaction which—from a microbiological point of view—means that salt cave sites are completely unsuitable for the growth of bacteria. Hospitals for speleotherapy begun to appear in the nineteenth century to treat respiratory illnesses and continue their operation until today, even if their claims for healing are questioned by traditional medicine. From the murder of Eric Garner and George Floyd to migrant ships being turned away from land and searching on Google for “coronavirus symptoms,” the right to breathe has never been more urgent.

4. Freedom Cave

The Cave of Eileithyia is a sacred cave in Crete that was dedicated to Eileithyia, goddess of childbirth, protector of pregnant women, daughter of Zeus and Hera, and mother of Eros. Rock formations in its interior resemble female figures, most notably a stalagmite whose shape resembles a pregnant woman’s abdomen. From the Neolithic to the Roman eras, pregnant women would bring offerings and rub their bellies on a small depression that forms the navel with the belief that it would ensure an easy childbirth. Cave worship in the darkness brought new life. To this day, women visit the cave and leave flowers. However, a Christian saint has replaced the worship of Eileithyia: St. Eleutherius is now the protector of pregnant women. Eleutheria (phonetically very close to Eileithyia) means “freedom” in Greek. A pagan goddess mutated under the Christian filter into a male saint. Confinement during the pandemic has led to a rise in domestic abuse.11 Unable to leave the house, threatened women have been unable to reach for means of support.

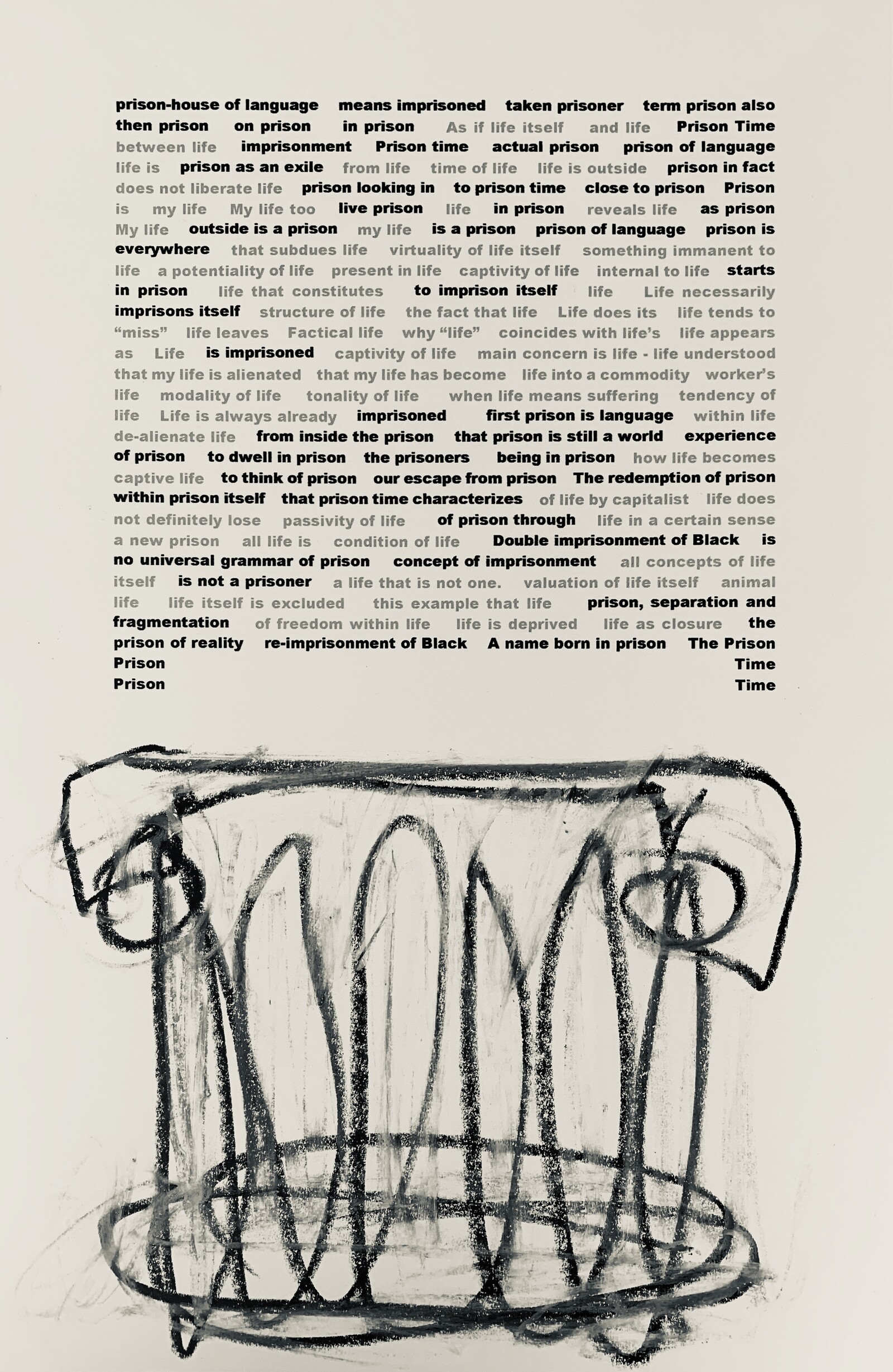

5. Man Cave

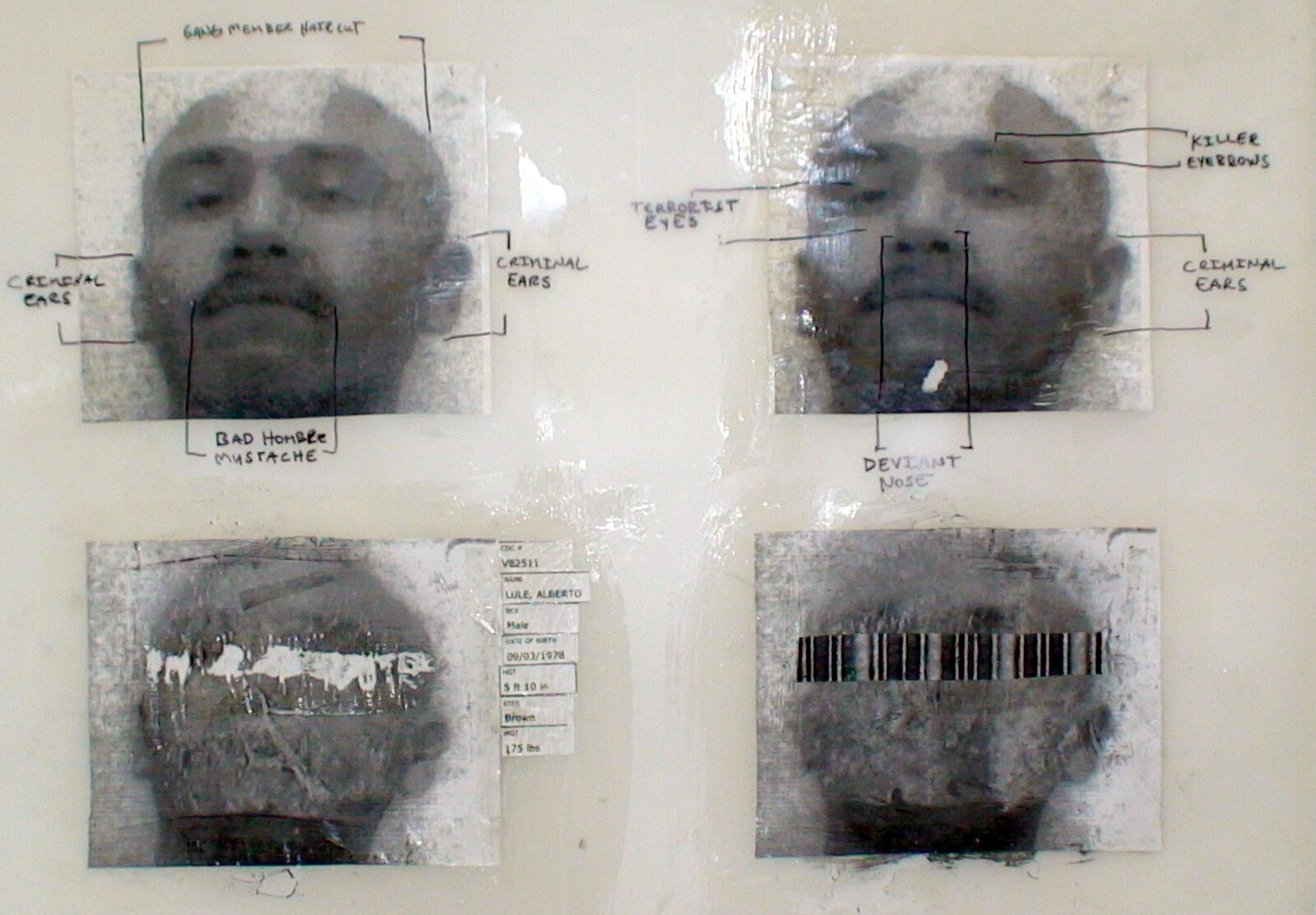

According to Wikipedia, “a man cave is a male retreat or sanctuary in a home…[it describes] a room where one or more male family members and optionally their friends are supposed to be able to do as they please, without fear of upsetting any female household members with their interior design choices.” Scientific literature about life in the Paleolithic era points to women as those mostly bound in caves. Texts predominantly speak of the stone age man. In comparison, there are few mentions how women spent their time.12 Recent research, however, supports the theory that most cave art was drawn by women.13 The interiority of cave life led to the development of female creativity, as cave surfaces became the means of communication.

The DIY Network television show Man Caves ran for almost ten years (2007–2016). In the show, hosts help men convert rooms into a male sanctuary, outfitting it with things like giant TVs screens, a bar, and plush couches.14 In the contemporary cave, surfaces become outfitted with more surfaces to aid the creativity of men. The pandemic led to a rise in home-improvement, with major US retailers catering to DIY projects like Home Depot seeing their profits and stock value rise exponentially.15

6. Cave of Quarantine

Due to the lack of daycare during lockdown, my kitchen table became my office. It was close to good light and views of nature (the garden), but quiet, uninterrupted work was still impossible. Dismal figures point to “hundreds of thousands of women, for whom the crisis has decimated their work opportunities, and for millions more, substantially increased their unpaid care work.”16

I moved a desk into the quiet, dark environs of the attic. The only sources of light up there were coming from two dormer windows on the roof above me. I could not see the sun, but the light was still blinding. I kept moving the desk during the day to avoid it, like Marianne in Melville’s story. Without any view to the outside, the only outlook in this newfound cave were its surfaces: striated wood patterns in the changing light. Never before have we become so attuned to surfaces. Over the course of weeks, we have become experts on how long the virus can live on mail, grocery bags, stainless steel, plastic, and fabric. We try to make sense of what we can’t see. Sanitizing, wiping, cleaning, or avoiding touch altogether; the banality of everyday surfaces has become a battleground, hosts of an invisible enemy.

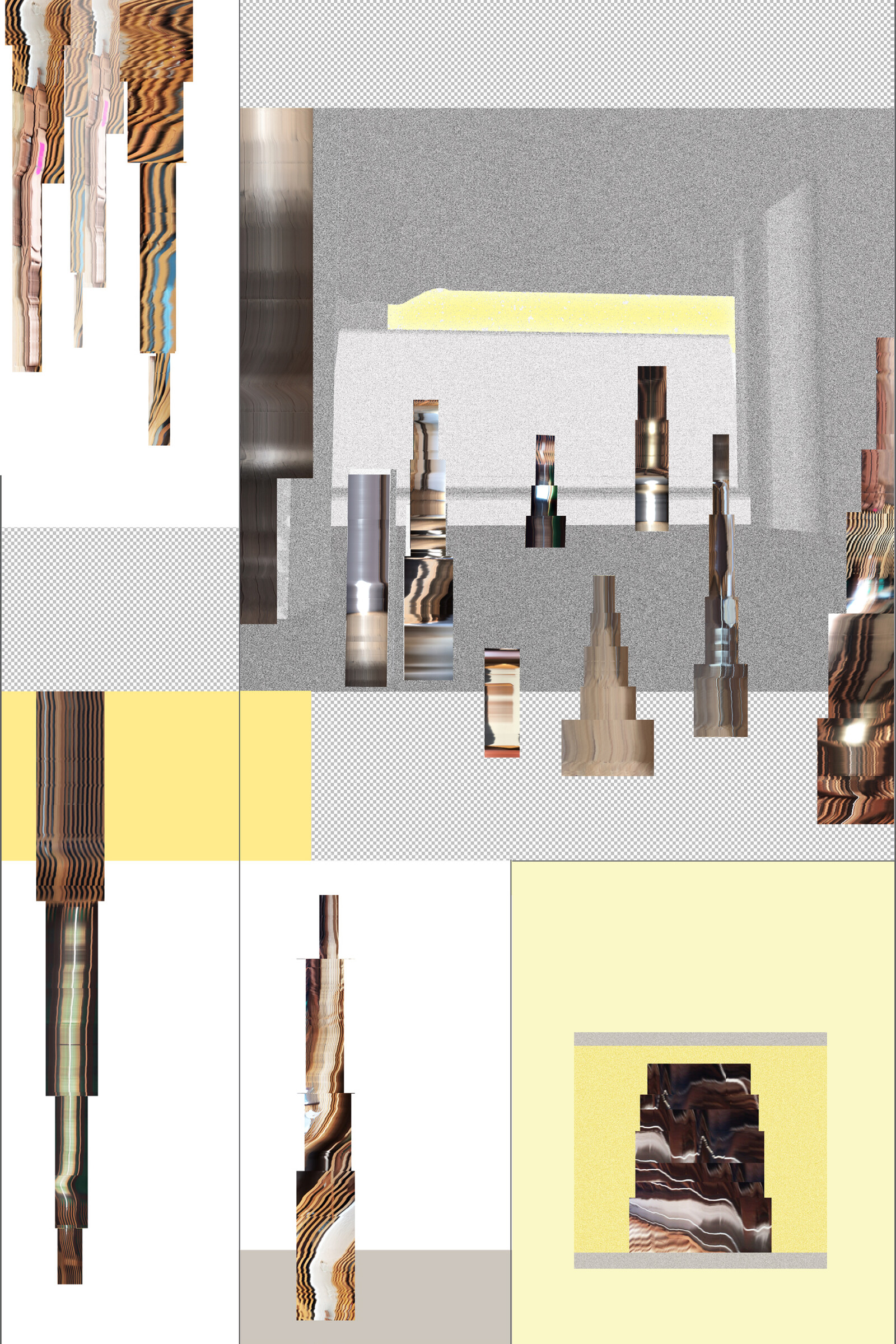

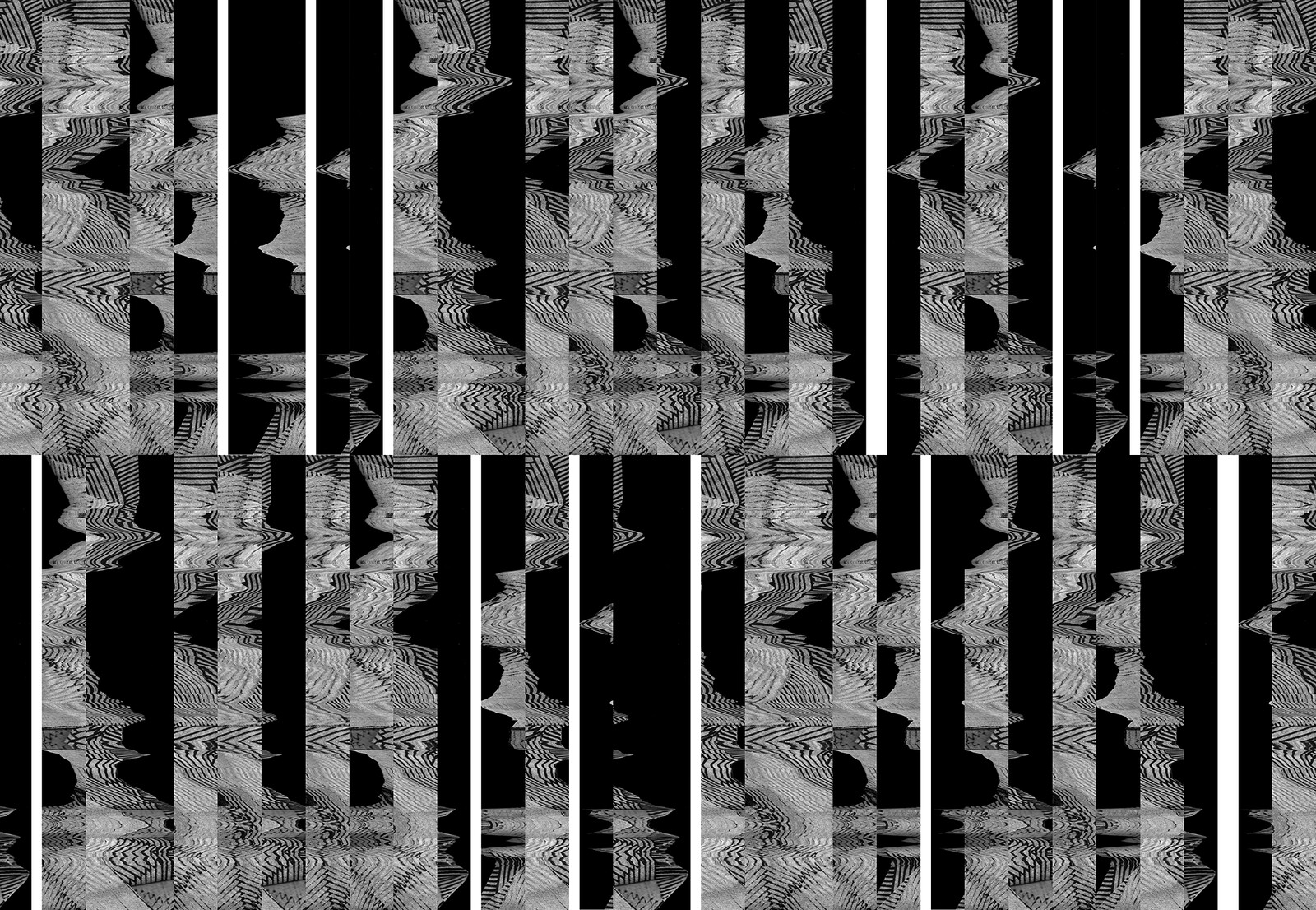

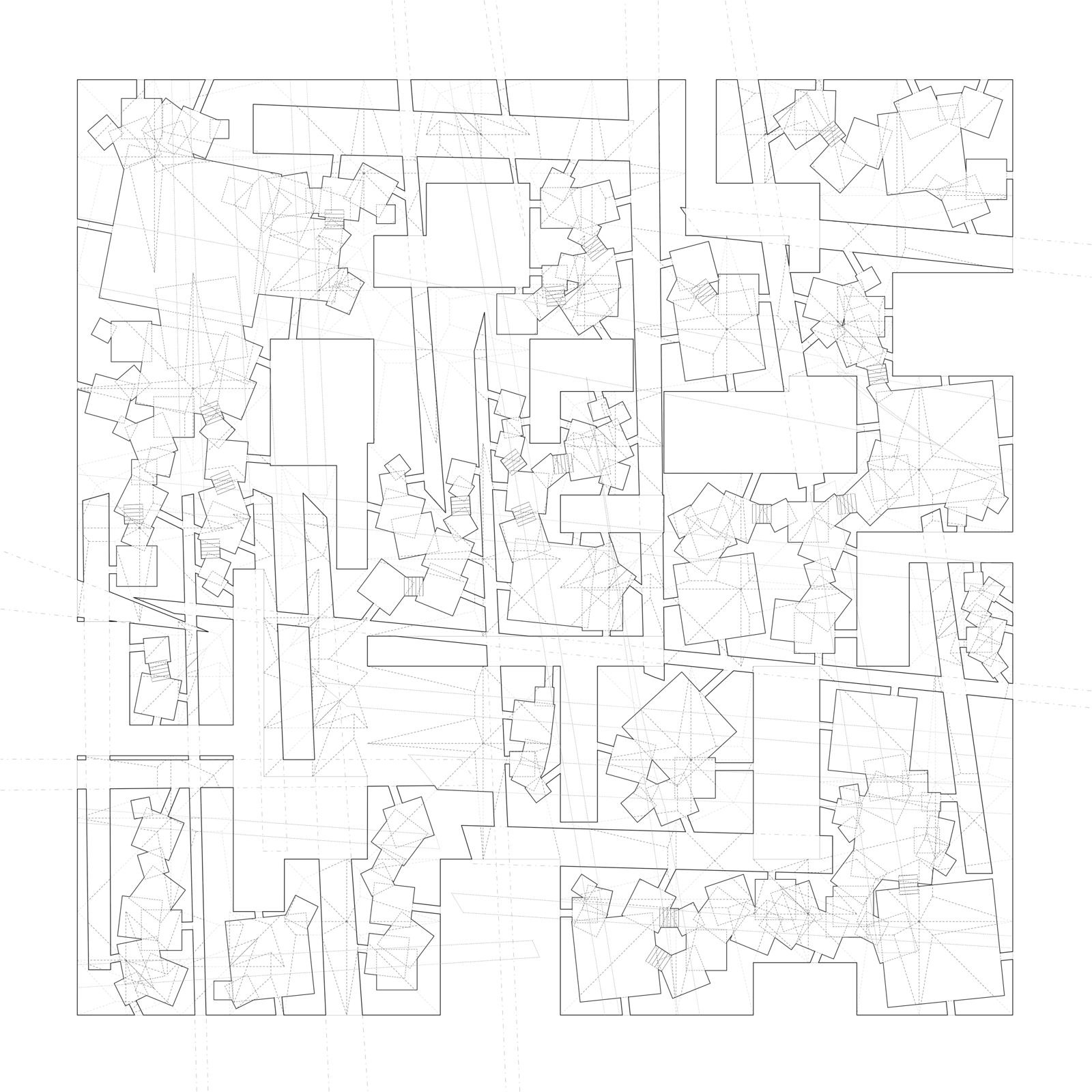

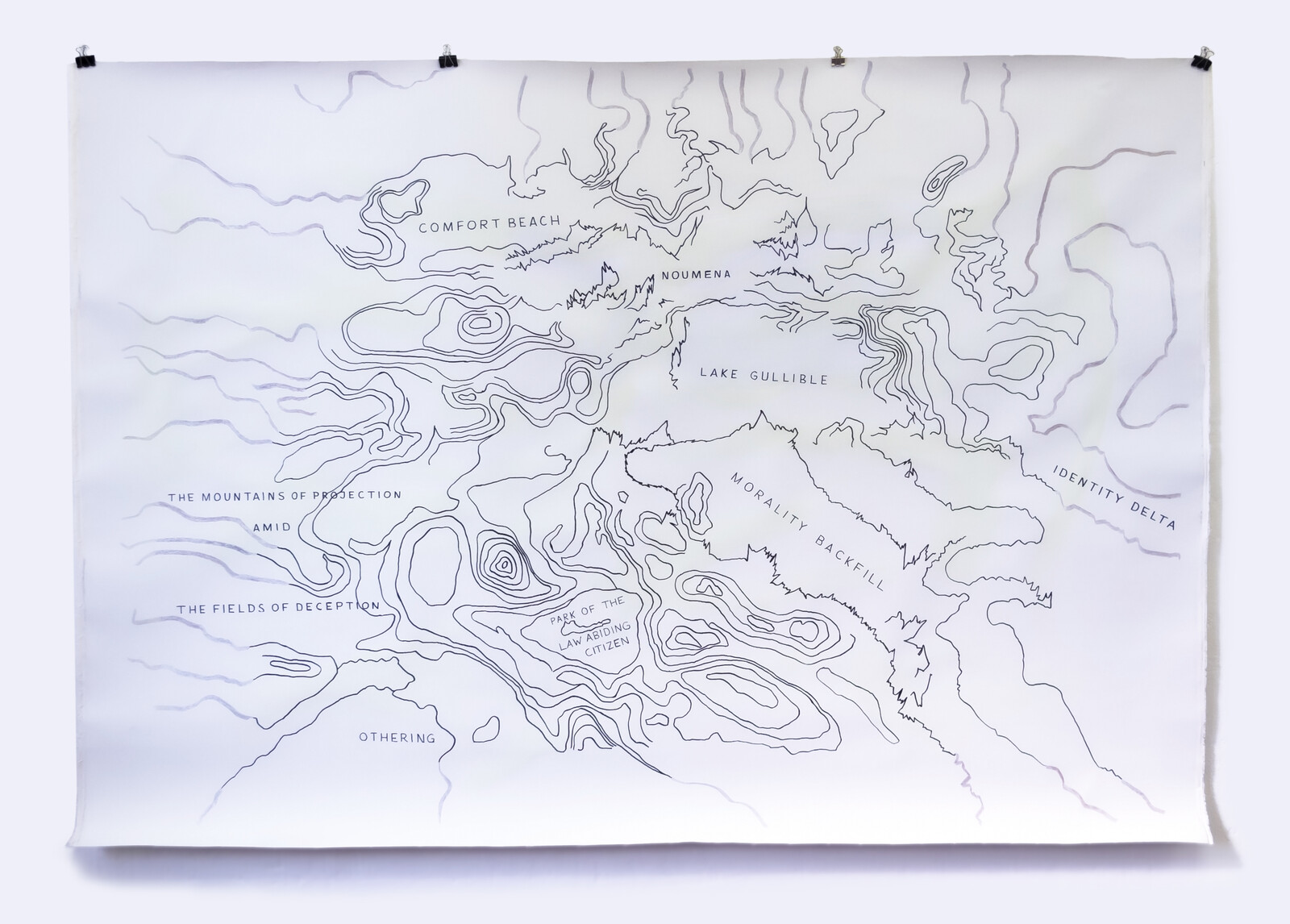

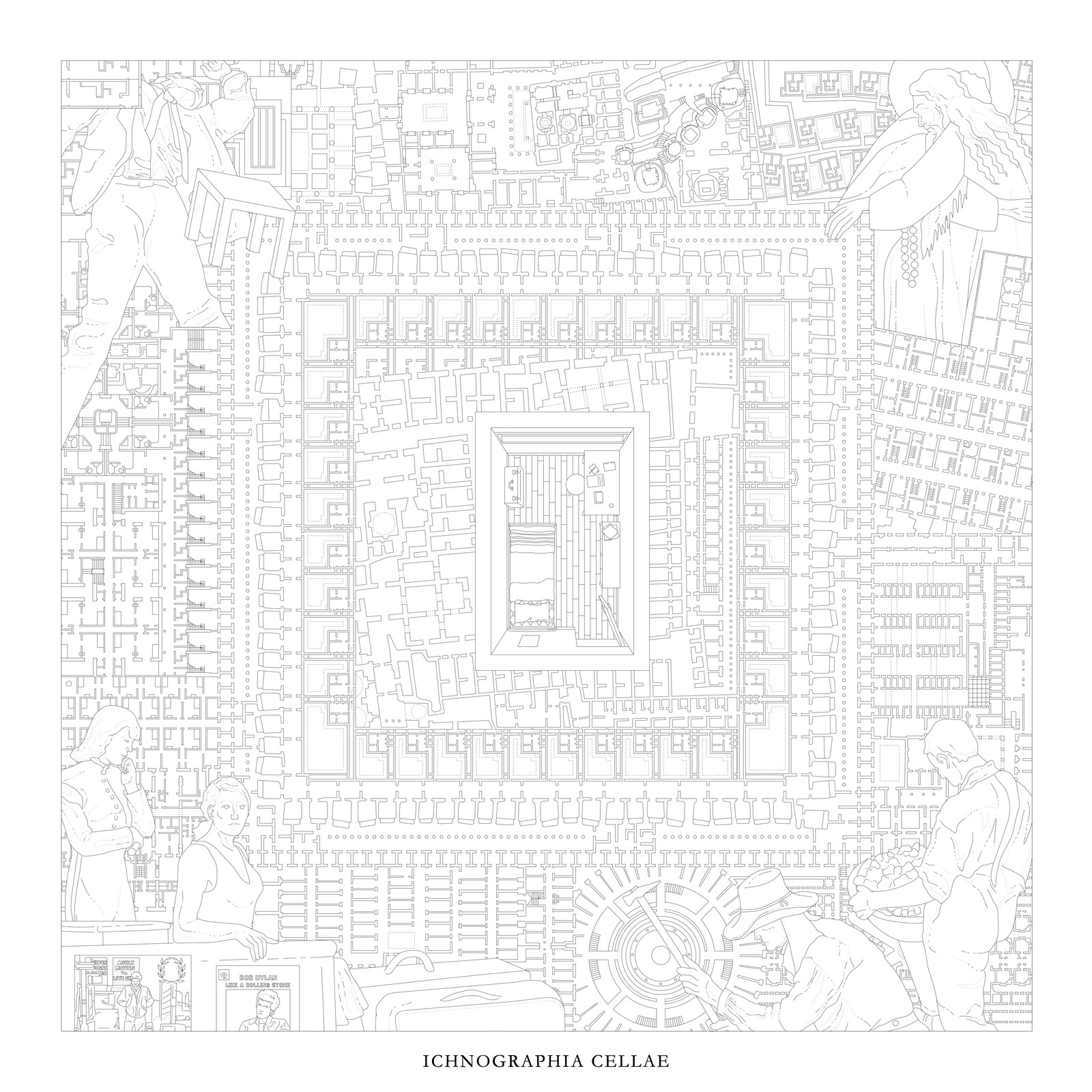

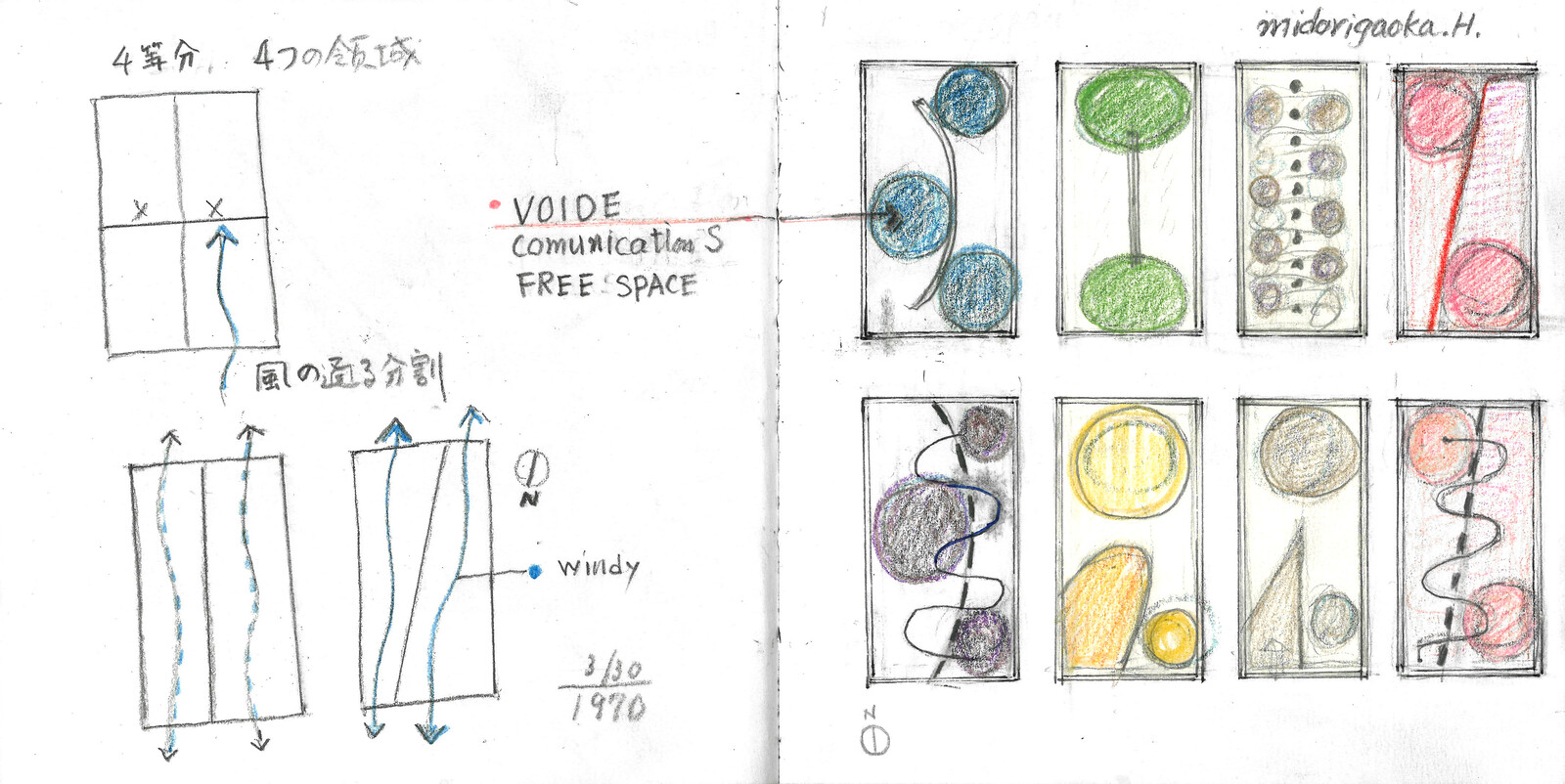

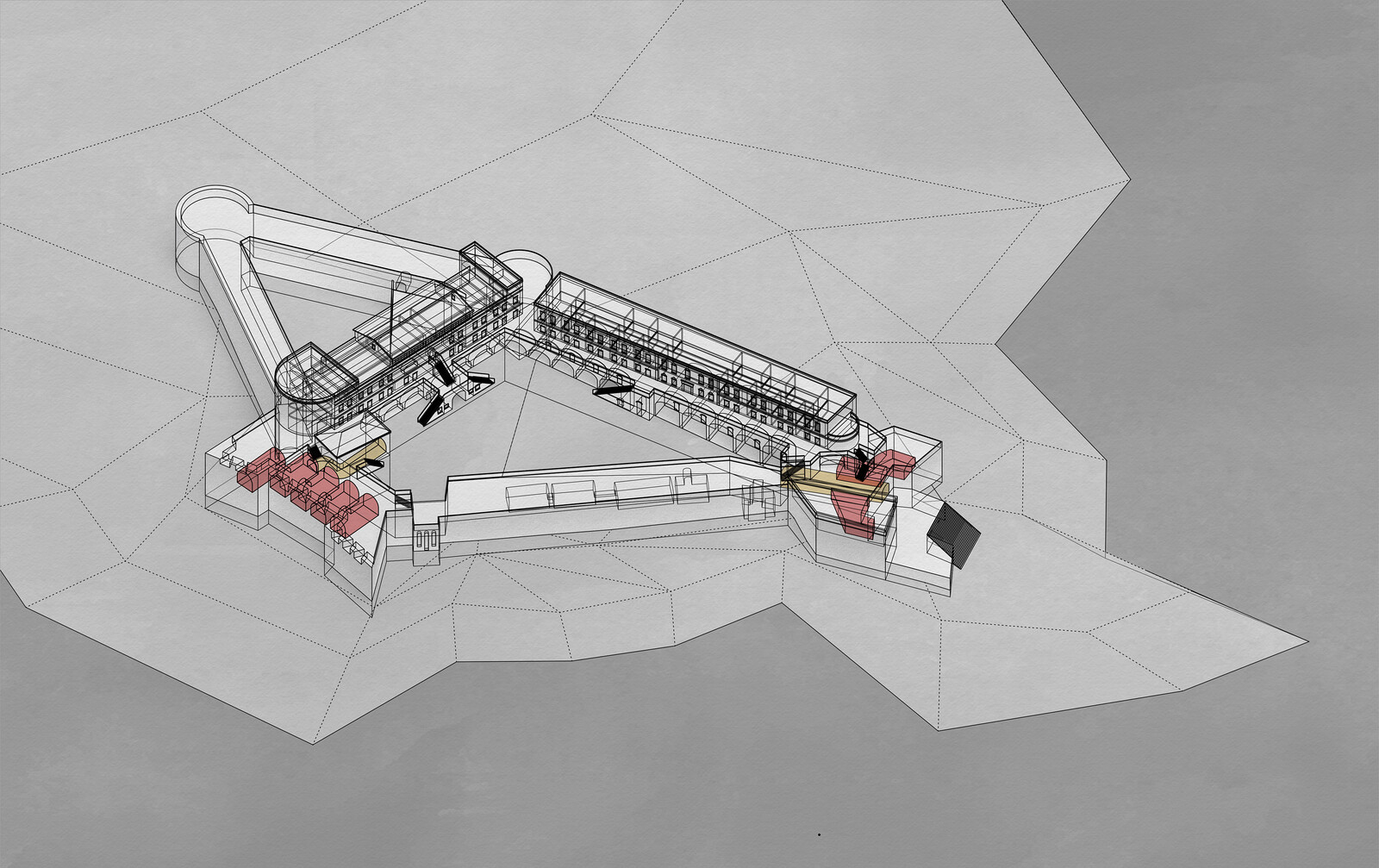

7. Cave Drawing

The drawing is composed of accumulated surface scanning of my attic. This slow scanning process distorts the surfaces of an ordinary timber roof structure, a mundane pile of bricks, reflections from the window, plastic sheathing, and turns them into geological strata. A new space is composed out of these scans, a cave of sorts, made of artificial surfaces; stalactites and stalagmites of time. The period spent in confinement resonates with the slow process of cave-making. It is a drawing of slowing down, with an occasional reflection. A breathing space made of surfaces without depth, yet with some illusion.

Lorraine Daston, Against Nature (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2019), 63.

I was inspired to write about Melville’s The Piazza as a response to the conversations in Nature Writing, a seminar taught by Michael Hampe in the fall of 2019 at ETH Zurich.

In Plato’s cave allegory, men chained deep in a cavernous interior face a wall; this is the limit of their vision. Behind them, people pass in front a fire while carrying different objects. Shadows of their movement are projected onto the cave wall. Hearing the voices of the men above them, the prisoners perceive the projected shadows as true forms. One of the men escapes his chains and manages to climb out. Seeing the sun for the first time, he realizes the falsehood of his previous experience: the forms on the wall, which he perceived as true, are mere projections. They are shadows and not “real” objects. He returns into the cave to tell the other chained men of his discovery. However, they are not interested in knowing the real source of the shadows produced into the wall.

Shadows are always a double, a duplicate of a form, created by a light source. In the cave allegory there are two light sources, the fire and the sun. Both cause objects to cast shadows, but for Plato it is only the sun that reveals truth.

Olivia Hershey and Hazel Barton, “The Microbial Diversity of Caves,” in Cave Ecology, eds. Oana Teodora Moldovan, Ľubomír Kováč, and Stuart Halse (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018), 70, ➝.

“How caves form,” British Geological Survey, 2017, ➝.

Thomas C. Barr, “Cave Ecology and the Evolution of Troglobites,” Evolutionary Biology 2 (1968): 43.

Ibid.

Stefano Mammola and Marco Isaia, “Cave Communities and Species Interactions,” in Cave Ecology, 255, ➝.

Jane Qiu, “How China’s ‘Bat Woman’ Hunted Down Viruses from SARS to the New Coronavirus,” Scientific American, June 19, 2020, ➝.

Kathryn Weedman Arthur, “Feminine Knowledge and Skill Reconsidered: Women and Flaked Stone Tools,” American Anthropologist 112, no. 2 (2010): 228–43.

Rachel Nuwer, “Ancient Women Artists May Be Responsible for Most Cave Art,” Smithsonian Magazine, October 9, 2013, ➝.

Theresa Howard, “Alltel website takes interactive campaign into man cave,” USA Today, August 16, 2007, ➝.

Trefis Team, “Home Depot’s Stock Up A Robust 65%: What’s Next?” Forbes, June 22, 2020, ➝.

Celina Ribeiro, “‘Pink-Collar Recession’: How the Covid-19 Crisis Could Set Back a Generation of Women,” The Guardian, May 23, 2020, ➝.

Confinement is a collaborative exhibition curated by gta exhibitions and e-flux Architecture, supported by the Adrian Weiss Stiftung and the ETH Zürich Foundation.