In Mumbai, the word “slum” carries not just a pejorative linguistic connotation, but also juridical weight. Since 1995, with passage of the Slum Rehabilitation Act (SRA), the designation “slum” has given its residents legal entitlement to rehabilitation—to be moved into a permanent structure, constructed by a private builder, at the behest of the government and at no cost to the “slum-dweller.”

The SRA gave flesh to a constitutionally enshrined right to live with human dignity, which has been interpreted in various Supreme Court rulings to include the right to adequate shelter. Between the 1960s and the 1990s, alongside and in spite of a slew of regulations designed to deliberately restrict population growth, Mumbai’s population soared. Throughout this time, very little housing was added to the city. As a result, informal housing and settlements became the means to provide housing en masse. The SRA provided a way of creating value from these sites for developers while also ensuring a better environment for the city’s poorly housed masses.

To be eligible for rehabilitation under the SRA, households had to prove that they had occupied that dwelling or have lived elsewhere in Mumbai since before 1995, popularly known as the “cut-off” date. This census strategy was employed not only to ensure that a massive stock of social housing could be created, but also to weed out more recent populations whose presence, the government claimed, could not be supported by the city’s infrastructure. By the same logic of not having sufficient resources, construction of this new housing was left to private developers. The government offered access to land cleared of slums as well as bonus air rights to developers who participated in the rehabilitation program for little more than the cost of constructing the free units. The private real estate sector, which was until then a rather sleepy industry, received a tremendous boost by the SRA. Benefits accrued up and down the food chain from builders and contractors to realtors, brokers, politicians, bureaucrats, and of course, buyers.

Initial activist support of the SRA as a way of kick-starting the production of much-needed social housing soon found that its application had unintended consequences. The goal of creating a just and equitable city became entangled with speculative practices of financialization, urban design, and new desires amongst residents for easy profits.

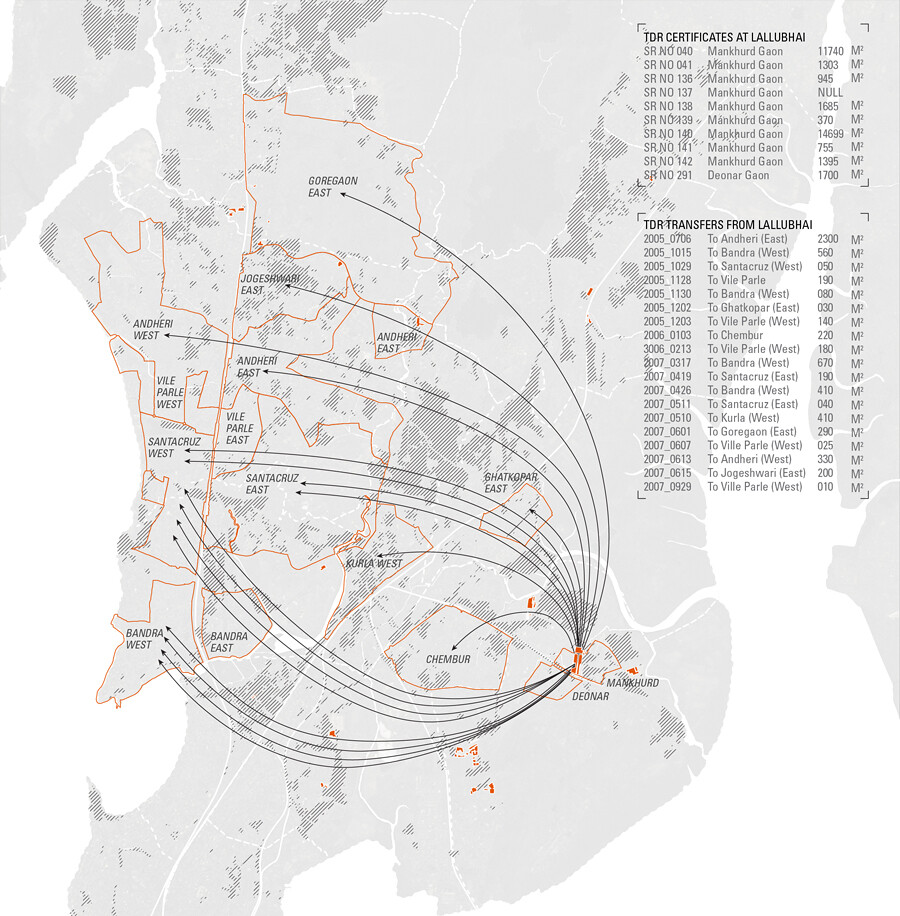

Viewed forensically, the Slum Rehabilitation Act, combined with a series of Development Control Regulations (DCRs) passed in 1991 that selectively increased FAR (Floor Area Ratio) on sites occupied by slums, turned slum redevelopment into a highly profitable game. The increase in FAR granted by DCRs was passed onto builders for the development of properties either in situ, or transferred onto other parcels as air rights. Thus, neighborhoods with lower land values, particularly along Mumbai’s eastern shore, became huge catchment areas for rehabilitation projects. Yet instead of using all of the newly-allotted FAR for the rehabilitation of these neighborhoods’ residents, they were used to generate air rights for more high-value, speculative parcels to the north and to the west.

Map of TDR transfers from Lallubhai. Drawing: Vineet Diwadkar.

Between 1995 and 2010, approximately one million people were resettled from slums and other dilapidated structures in somewhere around 225 million square feet of newly constructed buildings. Some were resettled in order to redevelop the land their settlements occupied, while others were moved to make way for new transport infrastructure. According to journalist Nauzer Bharucha, 130 million square feet of air rights (or transferable development rights, TDR) were used by developers from 1997 to 2017 to “build towers.” Of these, 80 million square feet were generated from the redevelopment of slums alone.1

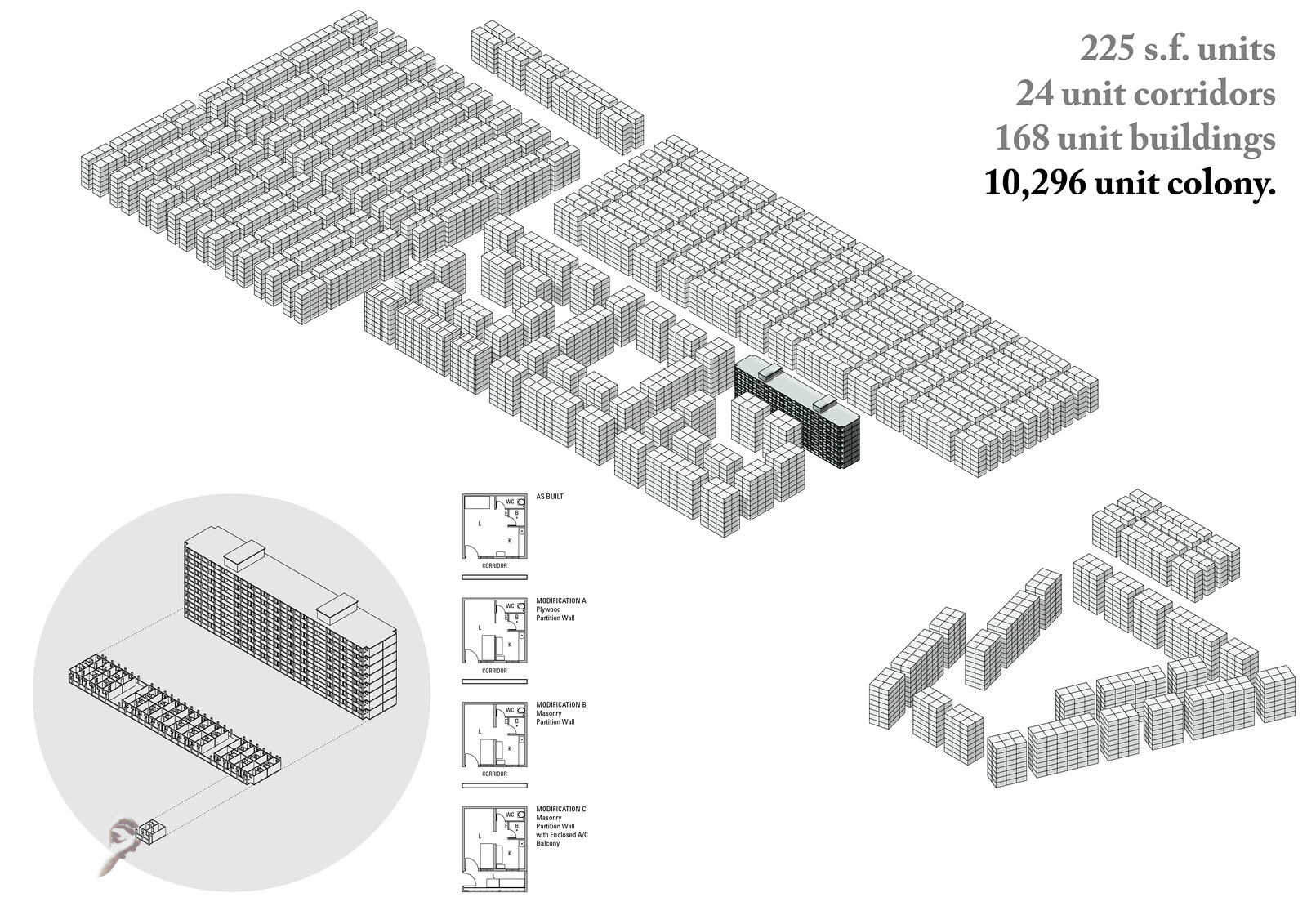

The active destruction and reconstruction of the urban fabric since the passage of the Slum Rehabilitation Act has radically transformed Mumbai’s physiognomy. From intimate to immense, these changes can be tracked through new morphologies and typologies emerging across the city. SRA resettles former slum residents into standardized units of 225 square feet, a figure presumably extrapolated from the 10×20 or 10×10 units common to many of the slum settlements in Mumbai. This is housing produced by the numbers, where the standard area of the rehabilitation unit is combined with the size of the rehabilitation site and the available air rights to determine the maximum number of units that can be double-loaded along dark corridors and dismal stairwells.

These new buildings embody an aspiration for producing mass social housing while at the same time building contempt for those very people they intend to resettle. Parcels of land become playgrounds for calculating the maximum numbers of people that can be squeezed into them, while creating maximum social distance between those resettled and wealthier classes. One housing typology this has resulted in, which places rehabilitation housing right next to new market-rate housing or commercial “towers,” has become common in certain parts of the city.

Sewri development, Mumbai, 2000 and 2015. Drawing: Vineet Diwadkar, Farzan Dalal, and Riddhima Khedkar.

This juxtaposed development is often seen in central Mumbai, once the city’s industrial hub with a concentration of more than 150 textile mills. One development in the Sewri neighborhood, located between the textile mill district and the docklands, took place on a site originally occupied by a slum of 144 households. These households were resettled on site, in one of three rehab buildings at the same location. But because rules dictated that the bonus FAR generated by this resettlement had to be consumed on the same plot, a twenty-four-story private apartment tower was constructed right next to the three slum rehab towers, placing them in a permanent shadow. The skyscraper next to the rehab building dominates the perspectival space around it. Furthermore, the process that brought it into being—the socioeconomic and technical envelope that configures its form and that of its companion, the rehabilitation building—is nakedly visible, producing a distance that is built into the future of this neighborhood and the lives of its residents.

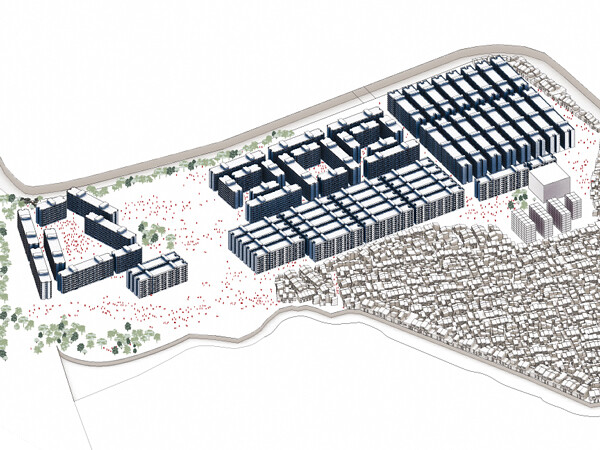

The other typology that has resulted from this process is that of the rehabilitation colony, where large numbers of buildings are clustered together on a single, large plot of land. Such colonies have been built mainly in Mumbai’s northern suburbs, where many industrial estates have been decommissioned as industries move out of the city. Lallubhai Compound (LBC) in northeast Mumbai, for instance, is a cluster of sixty-five resettlement buildings on an industrial brownfield site, adjacent to a large slum and cut off from visibility and transportation. Its five- to seven-story structures house approximately one hundred thousand people from distant corners of Mumbai. Many of LBC’s residents today were “project affected persons,” or PAPs, and displaced by the World Bank-funded Mumbai Urban Transport Project. Rehabilitation was promised within a small radius of their original homes, but for most, relocation meant moving more than twenty kilometers away and losing all connection to their networks of friends, family, and livelihood.

Lallubhai Compound next to Sathenagar Slum. Drawing: Vineet Diwadkar, Farzan Dalal, and Riddhima Khedkar.

LBC is barely fifteen years old and is already in an advanced state of decay.2 Many residents have been unable to afford the complex’s monthly maintenance fee, forcing them to sell their “free” units and move back into more precarious forms of housing. Most buildings at are separated by narrow alleys, some less than ten feet apart, leading only a fraction to have access to direct sunlight. A recent NGO study found that one in every ten households in LBC had a person infected with Tuberculosis. They concluded this was a direct result of the poor layout of buildings, the lack of open spaces, ventilation, and sanitation, declaring these buildings to be “designed for death.”3

Lallubhai Compound. Photo: Rajesh Vora.

Between buildings in Lallubhai Compound. Photo: Rajesh Vora.

Lallubhai Compound Spatial Allotments. Drawing: Vineet Diwadkar, Farzan Dalal, and Riddhima Khedkar.

Lallubhai Compound. Photo: Rajesh Vora.

Lallubhai Compound. Photo: Rajesh Vora.

The situation is even worse at Mahul, a former fishing village on Mumbai’s eastern shore that is now home to two oil refineries and a fertilizer plant. The Mahul rehabilitation colony, a densely packed cluster of seventy-two buildings, was empty when I first visited in 2009, waiting for residents to be allotted to live in them. Back then, it appeared as if these buildings had been constructed simply to harvest air rights for use elsewhere, where each square foot of development could fetch more than ten times its cost of construction in Mahul. Eventually the settlement became populated, but wave after wave of those who were allotted housing there initially refused to move in. Those families who had no choice but to live in it have been vigorously protesting against the toxic conditions in which they are forced to live out their lives.4

Perhaps a “topoanalysis” of the conditions under which urbanism is emerging is necessary to understand the effects of scaling up, of living at vertiginous heights, and the nightmare of being caught on the ground and off guard.5 The contemporary recipients of free housing constitute a new and diverse group, but they follow in the footsteps of earlier generations of Mumbaikars who adapted to multi-storied living over the course of the twentieth century. For these earlier generations, the shift to horizontal homes stacked on top of or beneath each other was both a formal and a cultural shift. From the barrack-like typology of working-class chawls, which shared toilet blocks and were strung along corridors open to the sky, to early vernacular experiments with multi-room, multi-story living still found in some of the older surviving neighborhoods of South Mumbai, there have been many iterations of form and feeling, construction and collectivity.6 Contemporary attempts at mass housing, under the auspices of the SRA, are qualitatively different insofar as they enfold and distribute density in completely new ways. They create new forms of congestion, trapping air, light, and people in new social and political dead-ends.

For Gaston Bachelard, the contrast between the house and the apartment alluded to the loss of intimacy in modern life. He describes a house as constituting “a body of images that give mankind proofs or illusions of stability,” images that are accessible in dream states.7 By contrast, the apartment buildings of Paris comprise dwellings that are “oneirically incomplete.” “In Paris there are no houses, and the inhabitants of the big city live in superimposed boxes… from the street to the roof, the rooms pile up one on top of the other, while the tent of a horizonless sky encloses the entire city.”8 Bachelard’s oneiric house and similar philosophical propositions appear deeply nostalgic today and may even constitute an “epistemological obstacle” to understanding the forms of housing, building and dwelling that unfold today under the “tent of a horizonless sky.”

One of the early residents of LBC, M., recalled to me how, shortly after moving, he only realized that the majority of the residents in the building across from his were Muslim when they celebrated Eid. At that point, he did not know many of his new neighbors who had been resettled there from all over Mumbai like him, so he decided to get those from his building together to celebrate the anniversary of the Dalit Buddhist movement leader Babasaheb Ambedkar. Through such gestures of show and tell, LBC has largely remained free of conflict. According to M., exercises in building collectivity such as these become necessary in places like LBC, since it is likely the first occasion that many of these families have lived with people whom they share no networks or relations with, aside from living in the same place.

Modern urbanism imagines cities to grow through systematic building, ensuring smooth continuity and collectivity into the future. Mumbai is a city that grows through systematic unbuilding. While with modernity, there were foundational events of violence that preceded building, here building itself is the violent event, albeit slow and suffocating rather than quick and sudden. Instead of a practice that generates continuity and collectivity, building in Mumbai generates ruins, uncertain conditions, and unlikely alliances. As infrastructure, rehabilitation buildings are manifestations of the broken contract between the state and its most vulnerable citizens. Rehabilitation buildings are thus forecasting tools, weathervanes of urban collectives to come. Behind, underneath, or within these buildings might be a way of reading architecture to reach a possible form of collective life.

Nauzer Bharucha. “TDR Buildings of last 20 years can fill up 9 Nariman Points and BKC.” Times of India, August 13, 2017, ➝.

dna Correspondent, “Mankhurd PAP building a vertical slum,” DNA, June 9, 2011, ➝.

There are several news reports documenting the plight of Mahul residents, their protests and the court cases against the Municipal Corporation demanding the relocation of residents who have become critically ill due to living at the Mahul site. See, among others: Pallavi Pundir, “We visited the Mumbai neighbourhood so polluted its been declared unfit for human habitation,” Vice, September 17, 2019.

Topoanalysis is a concept developed by Gaston Bachelard in The Poetics of Space (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994).

For a rich exploration of the chawl as building typology and of its various social, cultural and political resonances, see: Neera Adarkar, ed., The Chawls of Mumbai: Galleries of Life (Mumbai: imprintOne, 2011).

Bachelard, 17.

Ibid., 26

Conditions is a collaboration between the Sharjah Architecture Triennial and Africa Is a Country, Ajam Media Collective, ArtReview, e-flux architecture, Jadaliyya, and Mada Masr, within the context of its inaugural edition, Rights of Future Generations.

Category

Subject

This paper draws on research conducted in Mumbai during several periods between 2009 and the present. The stories and images form part of two book length projects. The first of these, titled Speculative City is an ethnographic account of Mumbai’s spatial and social transformation in the twenty-first century and its entanglement with speculative practices of financialization, design, development and air rights trading to unpack the complex ways in which citizens navigate conditions of flux and uncertainty. The second project, titled 50 Ways to Game a City (under contract, UR Books) is a collaborative project, co-authored with architect and planner Vineet Diwadkar, in which we examine closely the physical dimensions of this transformation, providing a map to understand these transformations within their surrounding urban space. 50 Ways brings together cases that we have investigated using the tools of what we call spatial ethnography, bringing together visual and narrative research. We thank Farzan Dalal and Riddhima Khedkar for their painstaking work on the models and Rajesh Vora for additional documentary photography.

Conditions is a collaboration between the Sharjah Architecture Triennial and Africa Is a Country, Ajam Media Collective, ArtReview, e-flux architecture, Jadaliyya, and Mada Masr.