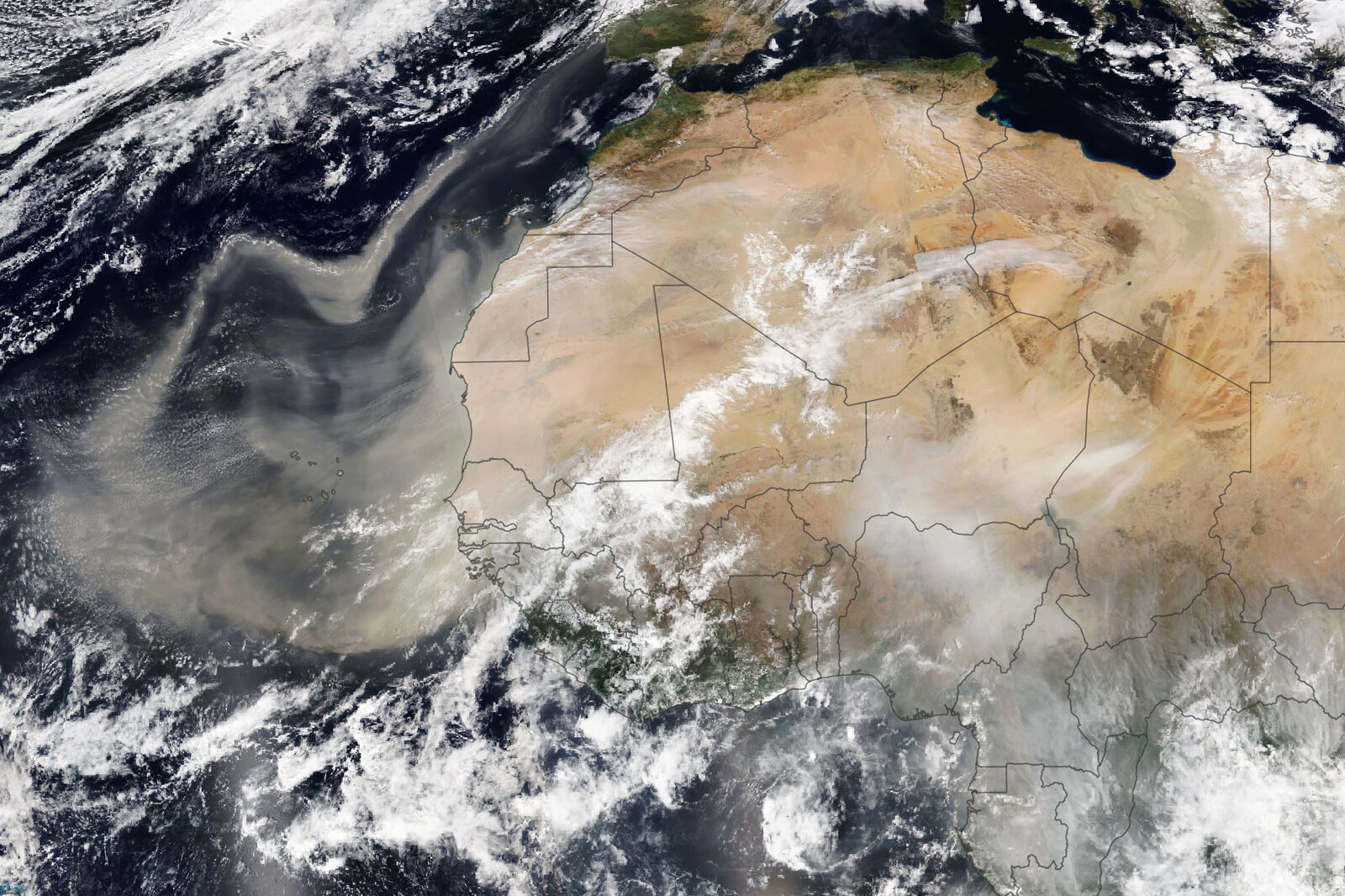

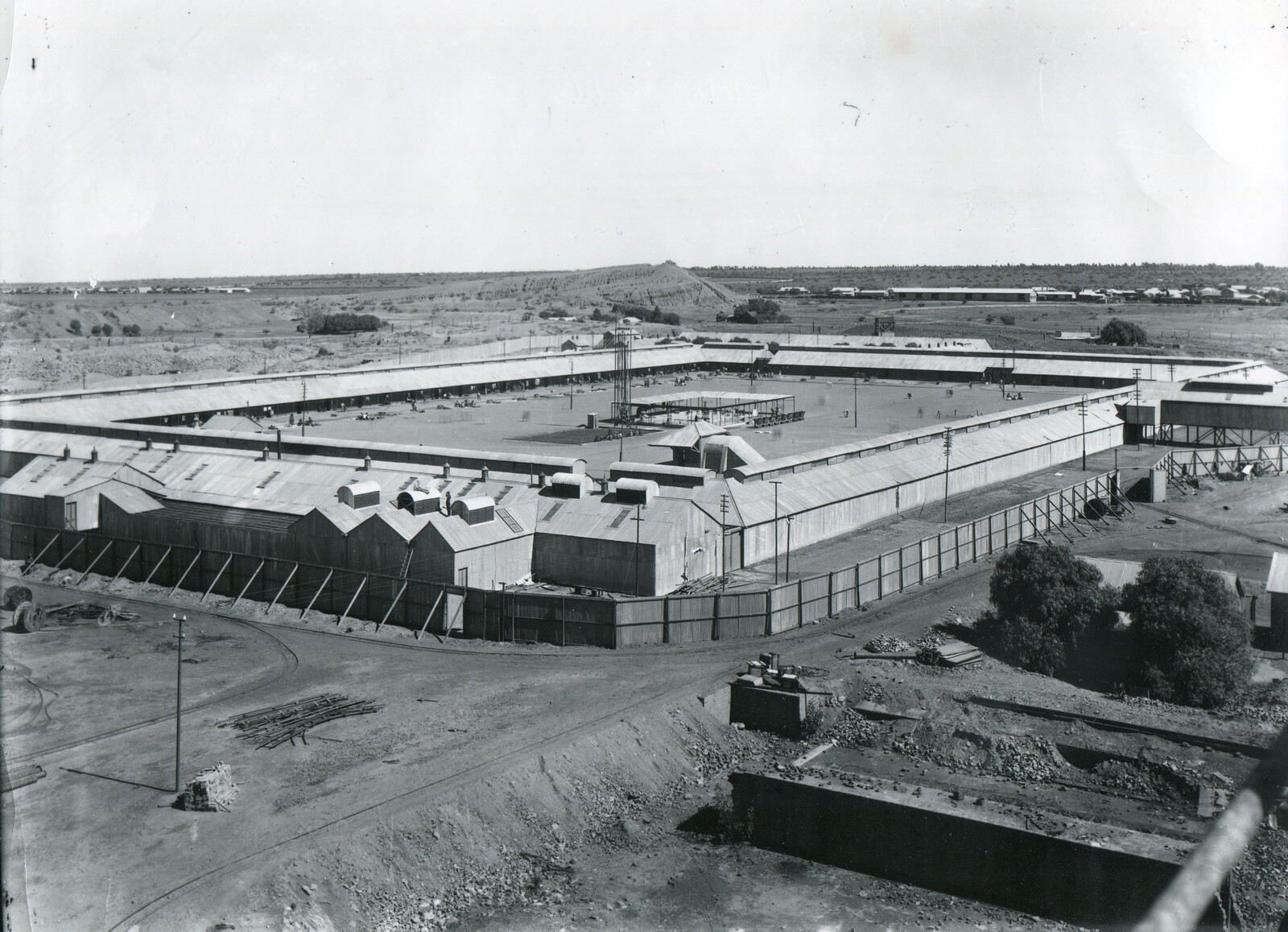

In her 2019 novel The Old Drift, Namwali Serpell writes about the Kariba Dam, southern Africa’s largest hydroelectric power source, and the great Zambezi River that flows through six African countries on its way to the Indian Ocean. She does this with a sense of historical acuity, ambiguity, and irony. The dam was commissioned by the Rhodesian government in the late 1950s, and was built by British and Italian engineers and a large African workforce at a place on the Zambezi that was known by waves of colonists and explorers as “the Old Drift.” Its construction forced 57,000 Tonga people, who had previously lived on, and from, the riverbanks and flood plains, to resettle inland. Kariba formed one pole of the new Zambian nation’s modern technological markers, as did Edward Nkoloso’s project to send Afronauts to the moon. One a wet, watery history; the other, a dry history of rising up to the skies from African grounds.

The novel opens at the Victoria Falls, as it was named by David Livingstone, and with a joke: “It sounds like a sentence. Victoria Falls. A prophecy.”1 The reader is then taken specifically to the drift five miles to the north of the falls, where the river is at its deepest and narrowest—the best spot, according to early colonists and marauders, for “drifting a body across,” and home to “excellent river-boys,” as the local Barotse are described in coloniality’s violent and racist discourse.2 This was also the port of entry into Northwestern Rhodesia, which would become Zambia upon independence. The opening of the story with a colonial archive is addressed, and partially undercut, by the mosquito chorus—an African and non-human riff on the ancient Greek chorus, which works as a metanarrative and eventually as a techno-animist hive-mind throughout the story. “This is the story of a nation—not a kingdom or a people,” they buzz, “so it begins, of course, with a white man.”3 Yet “if the story of a place is the story of its water,” as the chorus avers, where there is water there are mosquitoes. And where there is a river, it is not in its origin but in its capacity for drift, in its “chaos of capillarity,” that the story of history resides.4

As she parses early colonial drifting, wandering, violence, and appropriation along the Zambezi, Serpell renders the colonizing discourses of settler and native, woman and insect, with acuity and wit. She turns to the scene of the dam-building itself early in the book. In one of the novel’s major historically-rendered scenes, the Kariba Dam is nearly complete, and the Zambezi River is flooding earlier than usual:

Despite the rain, it was crawling with men, fly-like amongst the beetling machines. It looked like a mammoth corpse, half-dissected or half-rotten. They had already lost so many men to it.5

The flooding water seeps through a fault-line and starts to fill the inside of the unfinished dam; “a swirling thrusting deluge, read as blood because of the copper in the dust.”6 Within the next few months, the river valley would be underwater and multiple lives lost, including many Tonga, especially those who refused to be resettled away from their ancestral lands.

We could think of the history of Kariba as a history of planned violence. Making use of such a rubric, we can note, following Rob Nixon, that mega-dams like Kariba are “diversionary” in three senses:

They divert water—and through water, land—from the powerless to the powerful. But they also divert attention, their glistening enchantments throwing into shadow unimagined communities.7

This is echoed by Luck Makuyana, who researches colonial constructions of Kariba and Tonga water cosmologies:

In colonizing water, the Rhodesian government accomplished at least three imperial ends: the generation of “cheap” electricity, the establishment of a tourist resort (a white enclave of game reserves); and alienated human and non-human life from the Zambezi River Basin.8

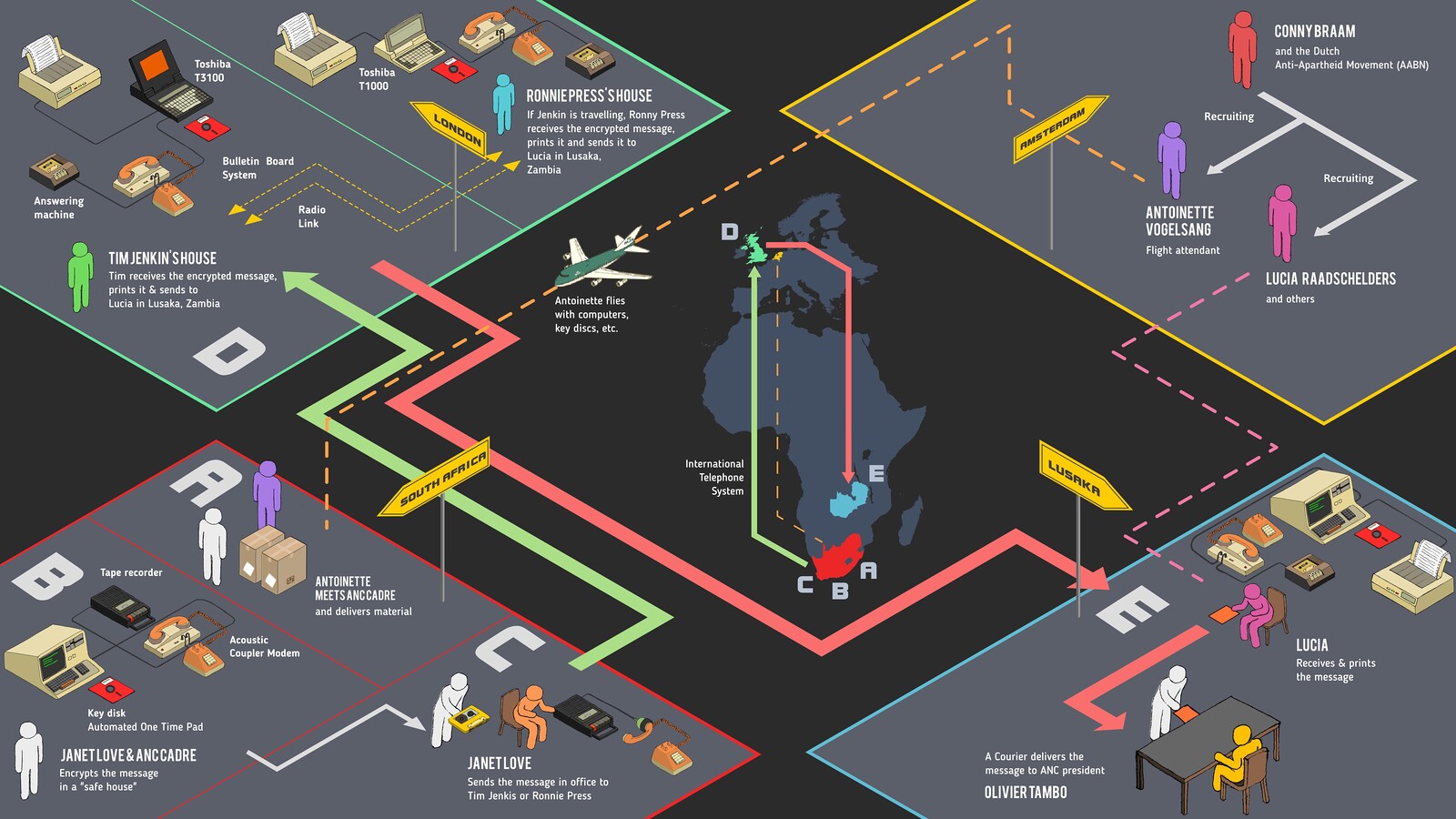

In their book Planned Violence, Elleke Boehmer and Dom Davies elaborate on the titular phrase—by reading Frantz Fanon’s views on urban planning in Algiers, amongst other sources—as an important concept for thinking about the coloniality of infrastructures.9 Planned violence plays out through the infrastructural materializations of colonialism’s exploitative agendas and its aftermaths, which can serve to cement and expand territorial control, to seize or exploit territory. If planned violence (as analyzed by Boehmer and Davies) draws from postcolonial studies that emphasize dialectical, relational, and entangled relationships between Africa and Europe, then coloniality articulates a chasm, as Arjun Appadurai sets out, often based on indigenous epistemologies from countries of the Global South.10 Tonga hydro-cosmologies play a significant role in Serpell’s rendering of the story—but so does climate change, a rubric that coloniality and its articulations often simply leave out.

The Old Drift is often referred to as a Zambian novel, but one of its many subversions is to reveal itself equally as a novel of southern Africa and of the Zambezi watershed itself. In the scene of the Kariba Dam construction, the site becomes something more monstrous than its modernist aspirations would allow: men appear as insects, crawling like flies in the mud, on a vast cement contraption that appears corpse-like in the rain, subject to a red deluge of copper dust that resembles blood. The scene reveals the multiple deaths and violent histories of labor and displacement contained in the dam’s construction, as well as its uncontainability—subject as it is to a river known for its extensive flooding—in “watertight” narratives of human progress and enlightenment.

We might also approach the coloniality of megastructures like Kariba through the notion of hydrocolonialism. The term, drawn initially from the work of Isabel Hofmeyr, understands water as an empire-wide space networked by oceans and rivers, one not only organized around the colonization of surface and groundwater and articulated by port cities, amongst other hydrological formations and systems, but also animated by competing hydrological traditions and hydro-epistemologies.11 As recognized by “the hydrocolonial,” southern African cities and regions are indelibly shaped by imperial and apartheid uses of water and through biopolitical violence against what human life hydrologically entails. The human, infrahuman, and nonhuman bodies that are defined as waste and effluent in the pursuit of affluence and a colonizing modernity, as Louise Bethlehem has shown, subtend the hydrocolonial.12 Water interlinks environmental, oceanic, and infrastructural histories, and a deepening engagement with the materiality of water requires that we think about southern Africa at large as a hydrological formation. Such work also speaks to the affective dimensions of water infrastructures—like how Kariba figures as memory, cultural reference point, and historical understanding in the lives of Serpell’s intergenerational characters.

In the later parts of her book, Serpell deals with questions of postcolonial and post-independence infrastructural neglect, or what analysts of the infrastructural turn have sometimes referred to as infrastructure’s zero worlds.13 Serpell embeds such questions in a materialist turn, engineering an understanding of the processes of water on rock and in relation to earth minerals. This materialist understanding is urgent, for the Kariba Dam has been in a dangerous, potentially fatal state since at least 2014. Infrastructural neglect and climate change have acted together to make a breech of the dam wall imminent. The torrents from the spillway, which were built on a seemingly solid bed of basalt, have eroded the bedrock over the years and carved a vast crater that has undercut the dam’s foundations. Heavy rain is likely to release water from the dam, in which case “a tsunami-like wall of water would rip through the Zambezi valley, reaching the Mozambique border within eight hours” and requiring tens of thousands of evacuations.14

Towards the final sections of Serpell’s novel, members of the youngest generation are plotting revolution, this time against the postcolonial state and its multiple modes of social neglect and oppression, including its unchecked and technologically-enhanced state power. The displaced Tonga, relocated to inland settlements when the dam was first being built, are “finally to be revenged.”15 Nodes of state-controlled digital systems, embedded in the walls of Kariba, are to be disarmed. But due to what characters refer to as “The Change,” “unseasonal rain” is pouring down heavily, again swelling the Zambezi and flooding the dam with a force that is unprecedented and unaccounted for in revolutionary schemes. The sluices flood and the dam walls break. A massive torrent of water is let loose. The dam’s foundations collapse. Extensive flooding creates a hydrological mashup of recombinant parts.16

At the end of the book, the human protagonist of the final section is submerged, mid-sentence, by the flood waters. In some respects, this is a wry return to the beginning of the novel, as well as to the time before Kariba was built: the power of the river itself breaks the modernist fictions of twentieth-century industrial and colonial modernity. And along with the river, it is the mosquitoes who persist: “we roil in the oldest of drifts—a slow, slant spin at the pit of the world, the darkest heart of them all.”17 The oldest drift of them all, the planet’s biochemical heart, its darkest heart, is again a wry invocation of the oldest adage of them all, of Africa as the heart of darkness, from which such brilliance is assumed not to emanate. Perhaps the mosquitoes are Serpell’s ultimate decolonizing gesture and signal.18

Serpell’s novel is, in a sense, the story of a flooding river that breaches the wall of political and narrative power and, in so doing, revenges coloniality’s violent disavowals of African shoreline communities and non-human worlds. Serpell also seeks to rewrite and decolonize the powers of drift, contesting its colonizing histories. Drifting, as Bronislaw Szersynski has written, can lead to a deeper understanding of the way all things move within the extended body of the earth.19 Acutely aware that drifting has a politics (mzungu, the southern African word for white people, means “people who wander”), Szersynski asks if there is a different means to approach drifting as critical practice, precisely in a planetary sense. The opposite of drift, he asserts, is locomotion, which has a front and back and moves differently through the world. But drift is what built the world we inhabit—that setting of sediment that became sedimentary rock; those concentrations of minerals into ores and deposits by hydrological flows.

One of the many decolonizing moments in Serpell’s novel is its rereading of “drift” as an alternative political, narrative, and material etymology of water and time in the aftermath of colonial violence. In his 2013 essay on the politics and poetics of infrastructure, Brian Larkin reminded us that infrastructures are conceptually unruly.20 Serpell’s novel, likewise, enables us to imagine what we could term infrastructure’s drift. Specifically, her book opens up registers of rain and flooding, what I call the pluvial or pluviality.21 The temporal dimensions of the pluvial as event and condition are what I have referred to as pluvial time, composed of multiple and unfolding temporalities. As we have seen, it rains with frequency across the novel, and flooding is seasonal, ubiquitous, and climate-change induced. Serpell’s novelistic attention to pluviality is what we might refer to as an earth infrastructure in the making, one that is biospheric in its capacities. One of the many tasks this novel sets for us is to consider how rain and flooding produce inhabitations of infrastructures outside the classical registers of engineering, architecture, and urban planning.

Namwali Serpell, The Old Drift (London: Penguin Random House, 2019), 3.

Ibid., 4.

Ibid., 1.

Ibid., 2.

Ibid., 70.

Ibid.

Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011).

Luck Makuyana, “Hydrocolonialism: A Hydro-critical Reading of Tonga People, Nyami-Nyami and Zambezi River Representations in Chosen Rhodesian/Zimbabwean Texts,” M.A. thesis, University of the Witwatersrand (2020).

Planned Violence: Post/Colonial Urban Infrastructure, Literature and Culture, eds. Elleke Boehmer and Dominic Davies (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

Arjun Appadurai, “Beyond Domination: The Future and Past of Decolonisation,” The Nation, March 9, 2021, ➝.

Isabel Hofmeyr, “Provisional Notes on Hydrocolonialism,” English Language Notes 57, no. 1 (2019): 11–20.

Louise Bethlehem, “Hydrocolonial Johannesburg,” forthcoming in Interventions, special issue on “Reading for Water,” Isabel Hofmeyr, Charne Lavery, and Sarah Nuttall eds. (2022).

Sarah Nuttall, “Afterword,” in Planned Violence, eds. Boehmer and Davies.

Chris Haslam, “The marooned baboon: Africa’s loneliest monkey,” BBC News, October 3, 2014, ➝.

Serpell, The Old Drift, 554.

“Lake Kariba would soon become a river. The dam would become a waterfall. And miles away, the Lusaka plateau … would become an island.” Ibid.

Ibid., 563.

For a more detailed, extended, and wide-ranging discussion of Serpell’s novel, see Sarah Nuttall, “On Pluviality: Reading for Rain in Namwali Serpell’s The Old Drift,” forthcoming in Interventions, special issue on “Reading for Water,” Isabel Hofmeyr, Charne Lavery, and Sarah Nuttall eds. (2022).

Bronislaw Szersynski, “Drift as a Planetary Phenomenon,” Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts 23, no. 7 (2018): 136–144.

Brian Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” Annual Review of Anthropology 42, no. 10 (2013): 327–343.

See especially Sarah Nuttall, “Pluvial Time/Wet Form,” New Literary History 51, no. 2 (2020): 455–471.

Coloniality of Infrastructure is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, Critical Urbanisms at the University of Basel, and the African Centre for Cities of the University of Cape Town.

Thanks to Kenny Cupers for his helpful suggestions while revising this essay.

Coloniality of Infrastructure is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, Critical Urbanisms at the University of Basel, and the African Centre for Cities of the University of Cape Town.