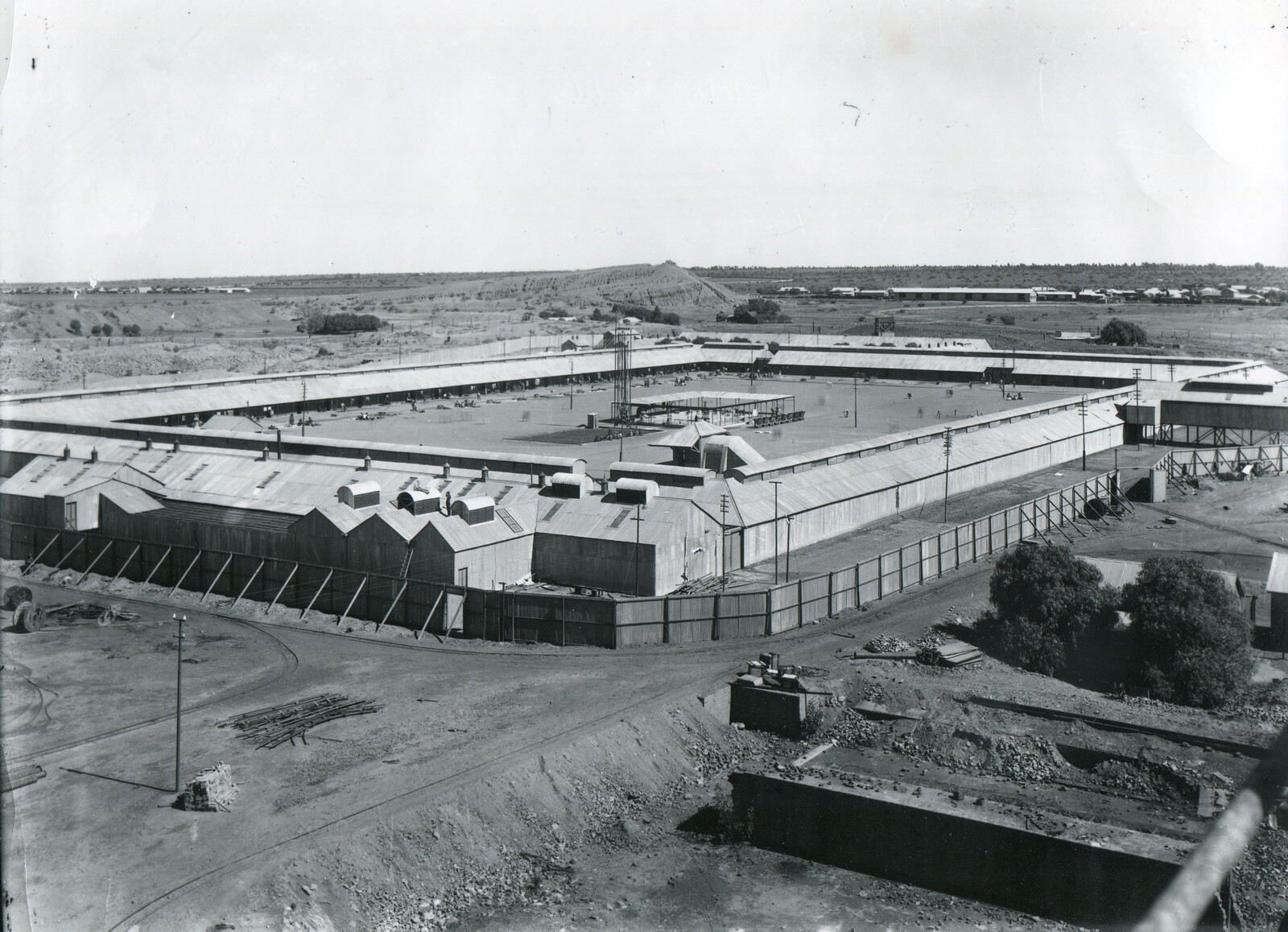

In the mid-twentieth century, apartheid South Africa was home to some of the largest, deepest, and most profitable mines in the world. Operating more than a mile below the earth’s surface, these mines simultaneously demanded the rigorous application of design standards, the extensive use of prefabricated material, and the flexibility to adapt to structurally unstable geological conditions. Deep underground, mineworkers soon found that the International System of Units—which shapes global standards—could not always generate the precise, accurate measurements that were necessary for their work. As a result, a new “creole” metrology was developed around the mines that not only challenged the universal logic of the metric system, but raised—and continues to raise—questions about the way the language of standards impacts the design and use of colonial infrastructure.

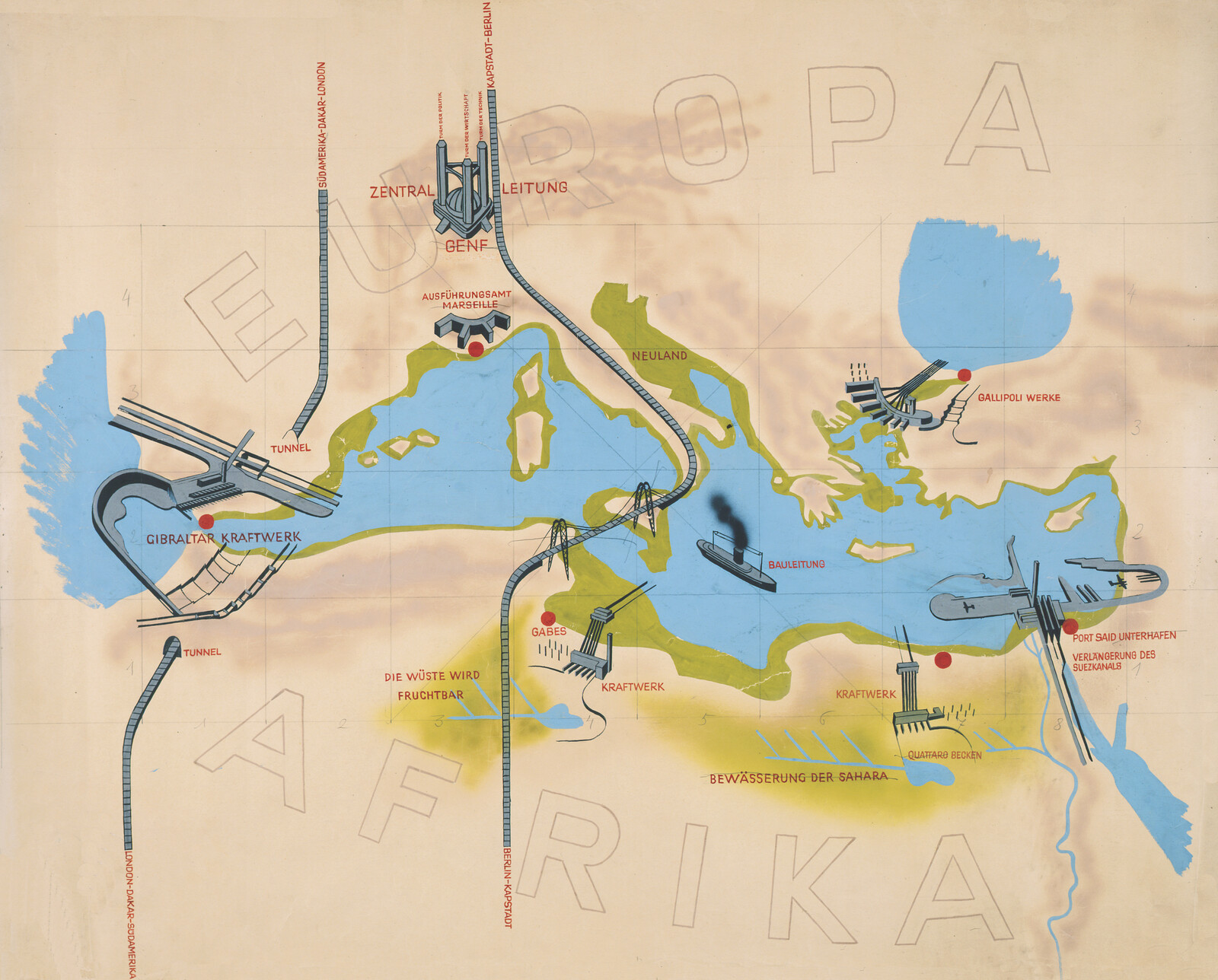

The notion of a “creole” metrology proposed here is tentative. It gestures to a longstanding debate among political theorists who have grappled with Léopold Sédar Senghor’s attempt to cast himself as a “Eurafrican cultural hybrid.” Historical studies suggest that the Senegalese president began to experiment with this sort of colonial language in the 1950s, in a bid to establish African leadership in the nascent European Union, and abandoned it by the mid-1960s.1 Yet his efforts to read a discarded colonial proposal—to make Eurafrica a political, economic, and cultural space that Africans and Europeans occupy as equals—raise fundamental questions about the material life of language, its organizational power, and its relation to physical infrastructure. While Senghor’s critics came to see hybridity as a concept that is overdetermined by biological relations of reproduction and inheritance, his questions about the material life of language have persisted.

After Senghor, Édouard Glissant turned to creoles—new languages that develop in relation to the oral contracts and linguistic negotiations that take place in trading zones—to analyze the unpredictable and unstable nature of shared space. Working against the logic of hybridity, Glissant questioned the value of tracing etymology, or form, back to the languages that creoles combine. Instead, he emphasized how the creolization process, which introduces parts of one language to another, is continuous and gathers momentum. Once it starts moving, it not only picks up speed, it also diffracts, so that the relationship between the languages that constitute the creole remain in flux. Its grammar, like its vocabulary, continues to bend and spread out so quickly that its standard can only be fluency. Speed, accuracy, and a certain ease-of-use tested in our bodies are critical to Glissant’s analysis. To account for a creole metrology, we too need to expand linguistic analysis to describe how the relationships between labor, design standards, and geological entities are negotiated.

I. Fanakalo ka lo nyuwan (Fanakalo for New Recruits)

Between 1953 and 2008, mining companies across South Africa required all new African laborers to pass a two-week course in a language called Fanakalo before they could be cleared to work underground. Recruits that did not speak a Nguni language had to master essential vocabulary very quickly. If they failed, they would lose their job and their right to reside in the Union of South Africa. For recruits that grew up speaking isiXhosa or isiZulu, however, the course would be a surreal experience—almost a beginner’s course in their native language.

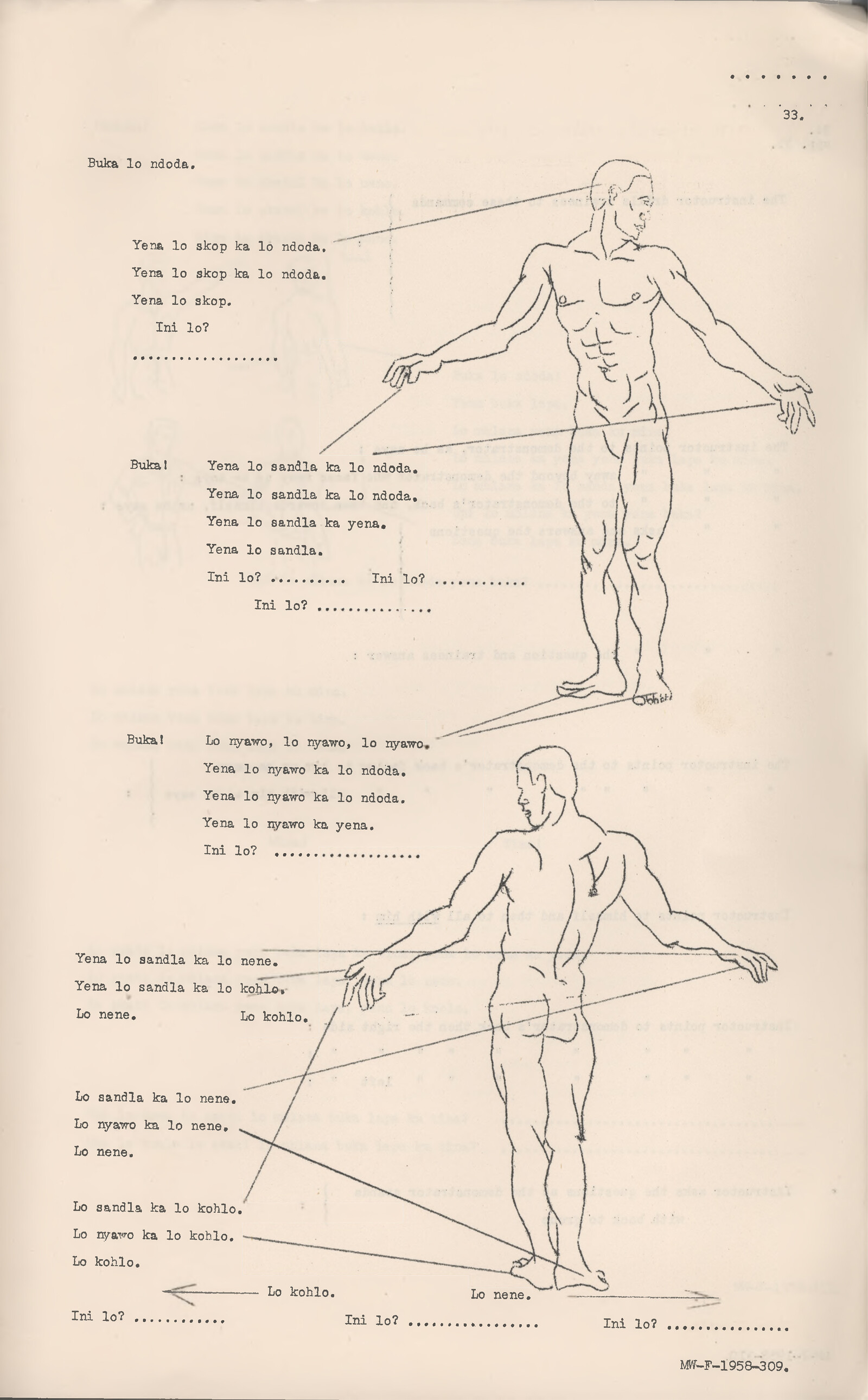

Ini lo? What is this?

Yena lo skop ka lo ndoda. This is the man’s head.

Yena lo skop ka lo ndoda. This is the man’s head.

Yena lo skop. This is the head.

Ini lo? What is this?

Linguists describe Fanakalo as a “pidgin of uncertain origins” and an “unusual contact language” whose lexicon draws heavily from isiZulu, while its syntax essentially conforms to the rules of English grammar.2 It is not clear exactly when or how Fanakalo entered the mining industry, but over the course of the twentieth century, miners and managers who needed to communicate across some forty different languages to complete their work in South Africa developed a “special register of technical terms” in this language.3

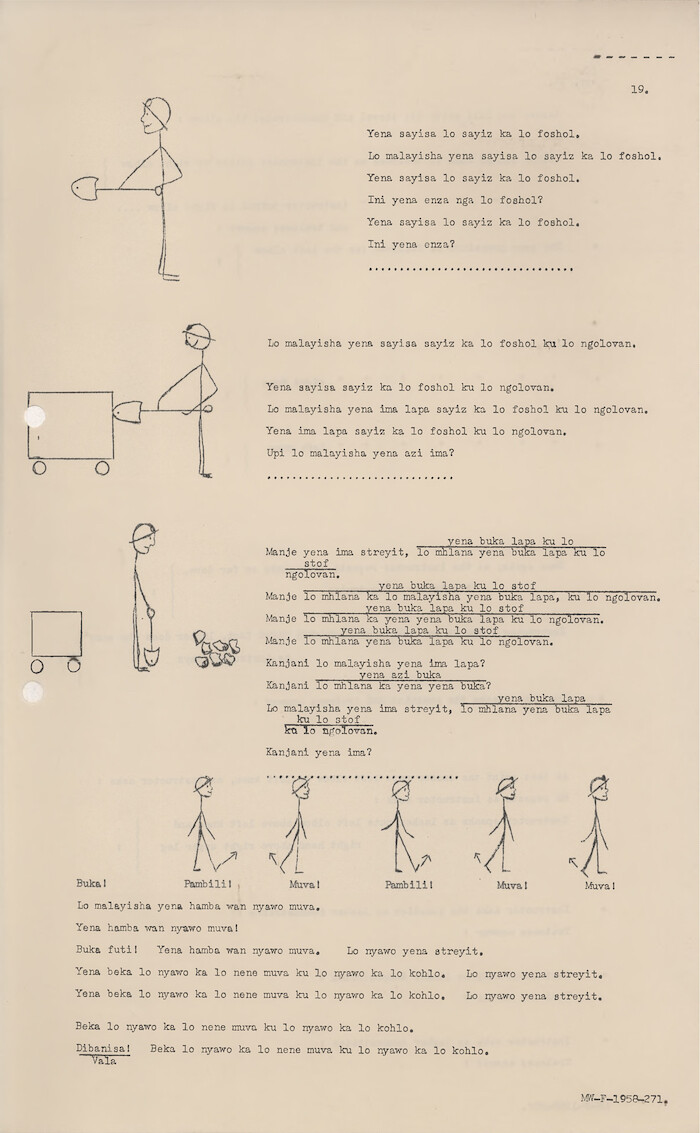

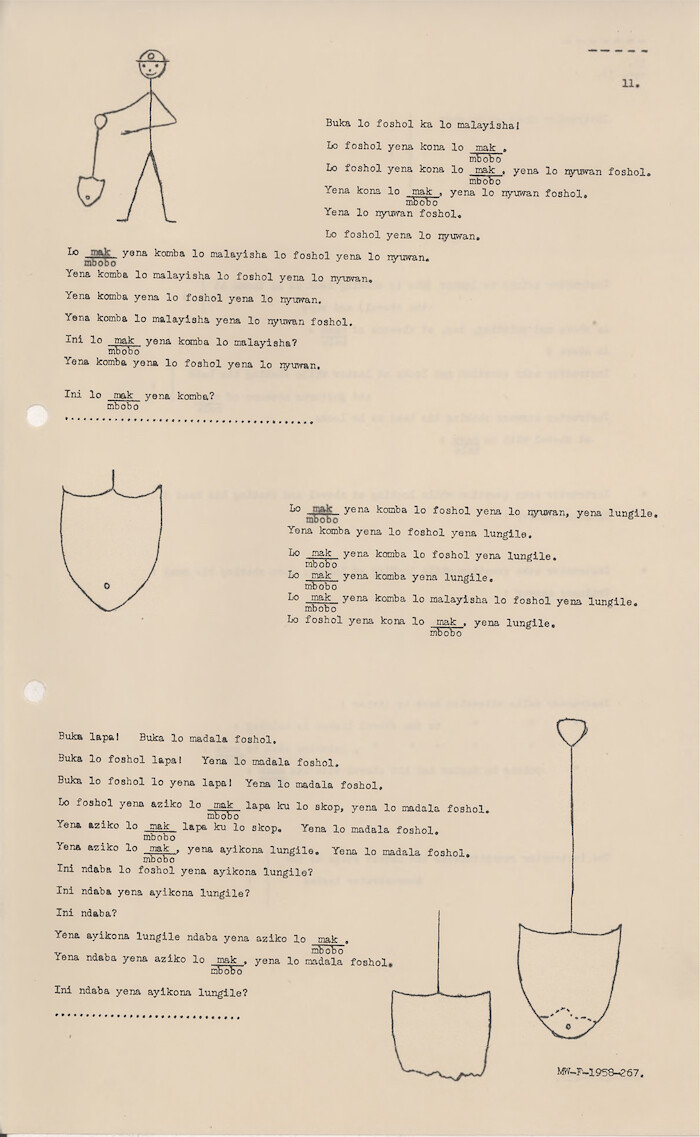

The two-week course was designed by Margaret Elizabeth Whyte, the wife of a Scottish missionary who worked to develop an adult literacy course for miners and sold her course documents to mining companies when she failed to attract students. Her course was designed to be implemented by a two-man teaching team. While the instructor would read out the names of each body part, he would point to the corresponding area on the body of his assistant. The word “skop” referred to the man’s head, but also the blade of the shovel. After saying the word, the assistant would then demonstrate how to choreograph the movement of the head and the shovel. The instructor would then proceed to drill the trainees on the new vocabulary with a question-and-answer sequence that articulated a number of distinct spatial relations between the rock, the workers’ bodies, and their tools.4

As new miners learned the parts of the body, they were also introduced to the sequence of movements that they would need to perform to shovel rock underground. After the recruits learned the words for head, hand, and foot, they learned how to hold, then how to use, the shovel. “Pick it up with your right hand, then take your left hand and place it a hand’s length away from the shovel’s head.”5 Proper technique lay in language as well as movement. The instructor’s training manual emphasized that every mteto, each response “must be given and acquired clearly and rhythmically, and the final linking must match the rhythm of the movement.”6 Recruits watched as the demonstrator bent his legs slightly at the knee, pushed the shovel under the pile of rock, and swung it up (across his body).

Lashers measure underground in M.E. Whyte’s Introduction to Oral Fanakalo, 1958. Bureau of Literacy and Literature, Historical Papers Research Archive, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. MW-F-1958-271.

II. Creole Metrology

This sequence of movements was fundamental to the operation of the mines, which required hundreds of thousands of “lashers,” the name for mineworkers who clear the rock and debris that falls after more highly-trained miners drill holes into rock, pack explosives, and detonate to advance deeper into the tunnel. The lasher’s job was to shovel rock into carts, which would be driven out of the mine to be crushed and treated in a series of chemical baths to extract precious metal. The lasher needed to be able to do this sequence without thinking, to pay attention instead to the dangers around him. In the deepest and most active shafts, mines struggled to keep the air temperature below 100ºF. New miners would need to vigilantly monitor their own bodies for signs of heat stress as well as focus on the movement of other men. They also needed to move in time with the team of lashers so that they would not hit anyone with debris or with the shovel by swinging at the wrong time. The movement of the shovel had to become as automatic as breathing.

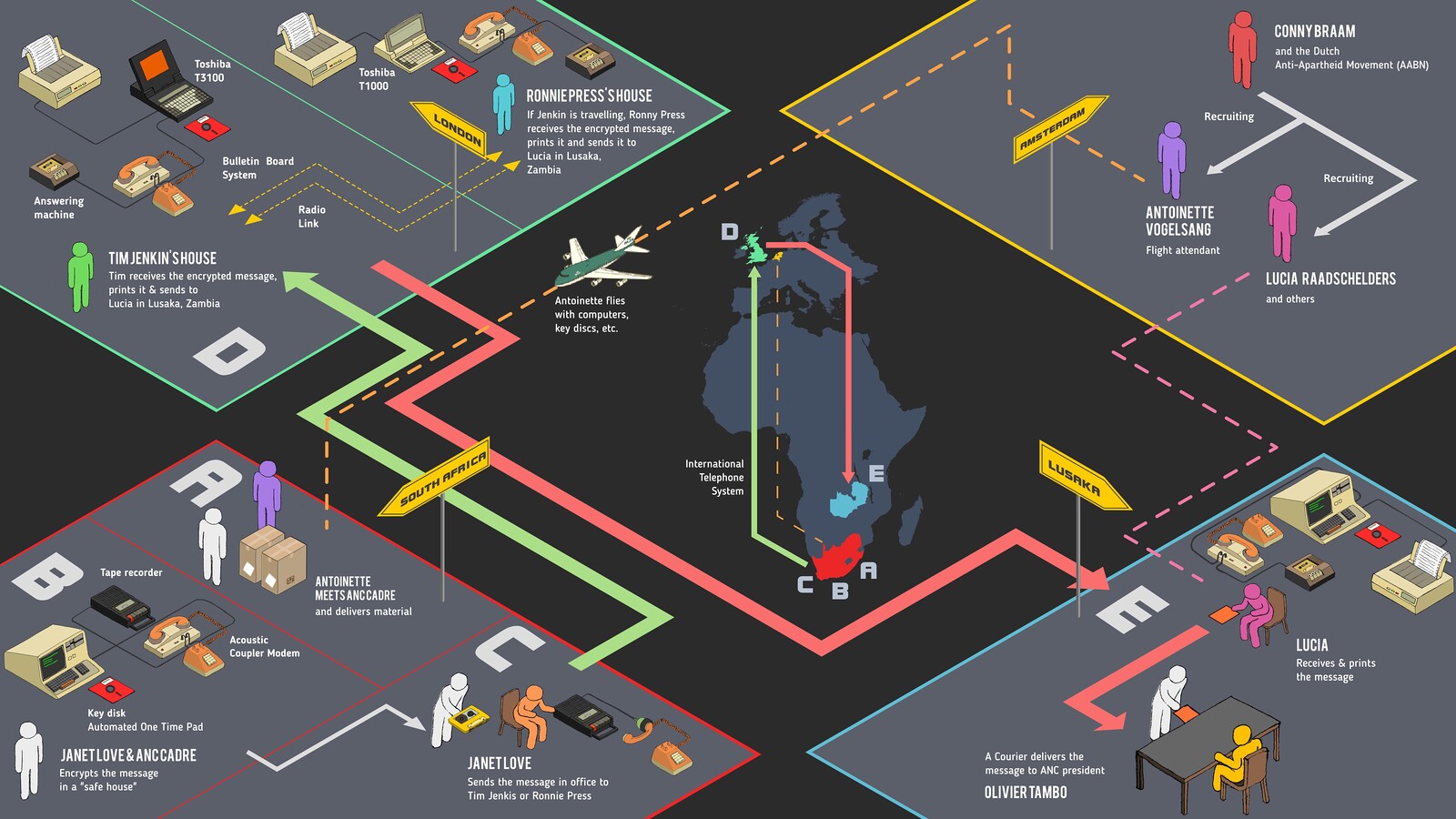

The Fanakalo course, which began by teaching miners the words necessary to the proper form for lashing, then taught new miners how to measure distance underground. Instructors started by calling the trainees’ attention to the way the lasher holds the shovel and stands up straight with his feet together. The lasher showed the trainees how to pick up the shovel by its handle with their right hand, to hold it level, horizontal, and pressed against the left side of their body to keep it steady, while indicating a shovel-length’s distance between himself and the cart.

The shovels used by mine workers were mass produced so that they could serve as meter sticks. Since earth and rock would wear down the tip of the blade with use, each shovel head was pierced with a small hole. Mine workers learned to check the condition of the shovel by looking at the eye of the blade. Thus, the extension of the deep-level mine was planned on the surface using standard international units, but realized by mine workers using a combination of standard units and “pit sense” that responds to and negotiates with the conditions of the earth. Moving between known units and unpredictable rock, the mine worker’s measurements made new space.

Trainees learned how to measure more than one shovel’s length and coordinate the movement of their bodies with the measured shovel. At the same time, they learned to say “Yena sayisa lo sayiz ka lo foshol,” which is not directly translatable. Literally, it means “I measure the size with the shovel,” but the verb “sayisa” is only used to describe the measurement of space or volume. One translation suggests that it means “to measure, to match, to take a size (rather of space or volume).”7 Perhaps, then, it would be more accurate to translate it as: “I make the match with the shovel,” or “I take the size with the shovel.” This translation depends on a kind of embodied knowledge that is difficult to transfer to another person by means of writing it down or verbalizing it. Fanakalo. Fana ka lo. Like this.

Lashers monitor the shovels’ wear in M.E. Whyte’s Introduction to Oral Fanakalo, 1958. Bureau of Literacy and Literature, Historical Papers Research Archive, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. MW-F-1958-267.

III. Theoretical Openings

Fanakalo was institutionalized in a colonial economy. It is unsurprising, then, that as the anti-apartheid movement consolidated power in the 1970s and 1980s, newly formed Black labor unions pressured the mining industry to use English rather than Fanakalo. Union leaders argued that the use of Fanakalo, which remained primarily an oral language used in the mines, limited worker training and job mobility. And yet, even after it was officially phased out of mine training programs in 2008, mineworkers have continued to use Fanakalo. Some have questioned the value of the National Union of Mineworkers’ campaign for standard or international English— and even argued that the use of English has helped blur the line between management and union officers. For instance, miners have reported that union officers help mines manipulate their safety records. Union representatives have also allegedly signed off on company reports that miscount work accidents, or claim that work injuries were sustained at home.8

In 2012, miners who rejected the leadership of the National Union of Mineworkers organized a wildcat strike at the Marikana platinum mine in Fanakalo. Strike observers were soon forced to reckon with the viciousness and the scale of the police response at Marikana, where South African police killed thirty-four people and injured hundreds when they fired live ammunition and rubber bullets at mineworkers assembled on a small hill. A number of studies have sought to reckon with the way the Marikana massacre reflects the changing nature of organized labor and strikes in (post)apartheid South Africa.9

The changing status of Fanakalo should also inform conceptual and methodological debates about (post)colonial infrastructure. While the National Union of Mineworkers recruited leaders that were literate and responsible for some of the most technically demanding jobs on the mines, new union movements promote mineworkers with little formal education. Their leaders are among the poorest paid mine employees, and some of those most vulnerable to the retrenchment campaigns that have left hundreds of thousands unemployed.

Modernist narratives of standardization have long centered on the use of written language. Architectural historians have demonstrated that efforts to standardize spelling and punctuation in the German Empire, for instance, fueled the development of the A4 paper system, the design of bureaucratic architecture capable of defining material and product quality, and, ultimately, a regulatory apparatus that promised to change production and distribution practices worldwide.10 But while European political theorists have emphasized the development of paper systems in the modern state, European governments failed to build robust bureaucracies in their colonies.11 In apartheid South Africa, the mining industry depended on Fanakalo to communicate with workers across many languages to secure reliable measurements in complex, dangerous, and quickly changing spaces. The creolization of international units presents further questions about the way experiments with language may come to pose a material challenge to colonial infrastructure. At the very least, the metrology it produced alerts us to the way measurement can create new and unstable space.

Trica Danielle Keaton, T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting, and Tyler Stovall, Black France/France Noire: The History and Politics of Blackness (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012); Gary Wilder, Freedom Time: Negritude, Decolonization, and the Future of the World (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015); Muriam Haleh Davis, “The Sahara as the ‘Cornerstone’ of Eurafrica: European Integration and Technical Sovereignty Seen from the Desert,” Journal of European Integration History 23, no. 1 (2017): 97–112.

Rajend Mesthrie, “Fanakalo as a Mining Language in South Africa: A New Overview,” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 258 (2019): 13–33.

Desmond T. Cole, “Fanagalo and the Bantu Languages in South Africa,” African Studies 12, no. 1 (1953): 1–9; Samuel D. Ngcongwane, “Fanakalo and the Zulu Language,” in The Languages We Speak, ed. Samuel D. Ngcongwane (KwaDlangezwa: University of Zululand, 1985); David Brown, “The basements of Babylon: Language and literacy on the South African gold mines,” Social Dynamics 14 (1988): 46–56; Crispen Chinguno, “Marikana massacre and strike violence post-apartheid,” Global Labour Journal 4, no. 2 (2013): 160–166.

“Fanakalo ka lo nyuwan,” Wits Historical Papers, BLL Records E5-6-1.

“Native Training Fanakalo Relating to Lashing, Adapted for Anglo American Corporation of South Africa Limited from Lo Foshal by M. Whyte,” Historical Papers Research Archive, University of the Witwatersrand, The Bureau of Literacy and Literature, 1945–1970, Collection Number AD1432, MW-F-1958-255.

Ibid., MW-F-1958-247.

Clement Doke, Daniel McKenzie Malcolm, and J.M.A. Sikakana, English-Zulu Dictionary (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1958).

Peter Alexander, Thapelo Lekgowa, Botsang Mmope, Luke Sinwell, and Bongani Xezwi, Marikana: A View from the Mountain and a Case to Answer (Aukland Park: Jacana Media, 2012): 52.

See for example: Alexander et al., Marikana; Keith Breckenridge, “Marikana and the Limits of Biopolitics: Themes in the Recent Scholarship of South African Mining,” Africa 84, no. 1 (2014): 151–161; Crispen Chinguno, “Marikana: Fragmentation, Precariousness, Strike Violence and Solidarity,” Review of African Political Economy 40, no. 138 (2013): 639–646; Don L. Donham, Violence in a Time of Liberation: Murder and Ethnicity at a South African Gold Mine, 1994 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011); Edward Webster, “Marikana and Beyond: New Dynamics in Strikes in South Africa,” Global Labour Journal: A Scholarly Forum for Global Labour Studies 8, no. 2 (2017): 139–158; Luke Sinwell with Siphiwe Mbatha, Peter Alexander, Immanuel Ness, Tim Pringle, and Malehoko Tshoaedi, The Spirit of Marikana: The Rise of Insurgent Trade Unionism in South Africa (London: Pluto Press, 2016).

See: Nader Vossoughian, “Standardization Reconsidered: Normierung in and after Ernst Neufert’s Bauentwurfslehre (1936),” Grey Room 54 (Winter 2014): 34–55; Nader Vossoughian, “From A4 Paper to the Octametric Brick: Ernst Neufert and the Geo-Politics of Standardisation in Nazi Germany,” The Journal of Architecture 20, no. 4 (2015): 675–698; Anna-Maria Meister, “Ernst Neufert’s ‘Lebensgestaltungslehre’: Formatting Life Beyond the Built,” BJHS Themes 5 (2020): 167–185; Jean-Louis Cohen, Architecture in Uniform: Designing and Building for World War II (Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture, 2011); Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure (London: Verso, 2014).

In South Africa, the mining industry sponsored research on fingerprinting and biometric registration in the absence of a state bureaucracy capable of governing the movement of African employees. See: Ivan Evans, Bureaucracy and Race: Native Administration in South Africa (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997); Fredrick Cooper, Africa Since 1940: The Past of the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002); Gaston Gordillo, “The Crucible of Citizenship: ID-Paper Fetishism in the Argentinean Chaco,” American Ethnologist 33, no. 2 (2006): 162–176; Keith Breckenridge, Biometric State: The Global Politics of Identification and Surveillance in South Africa, 1850 to the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Coloniality of Infrastructure is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, Critical Urbanisms at the University of Basel, and the African Centre for Cities of the University of Cape Town.