Garissa Lodge

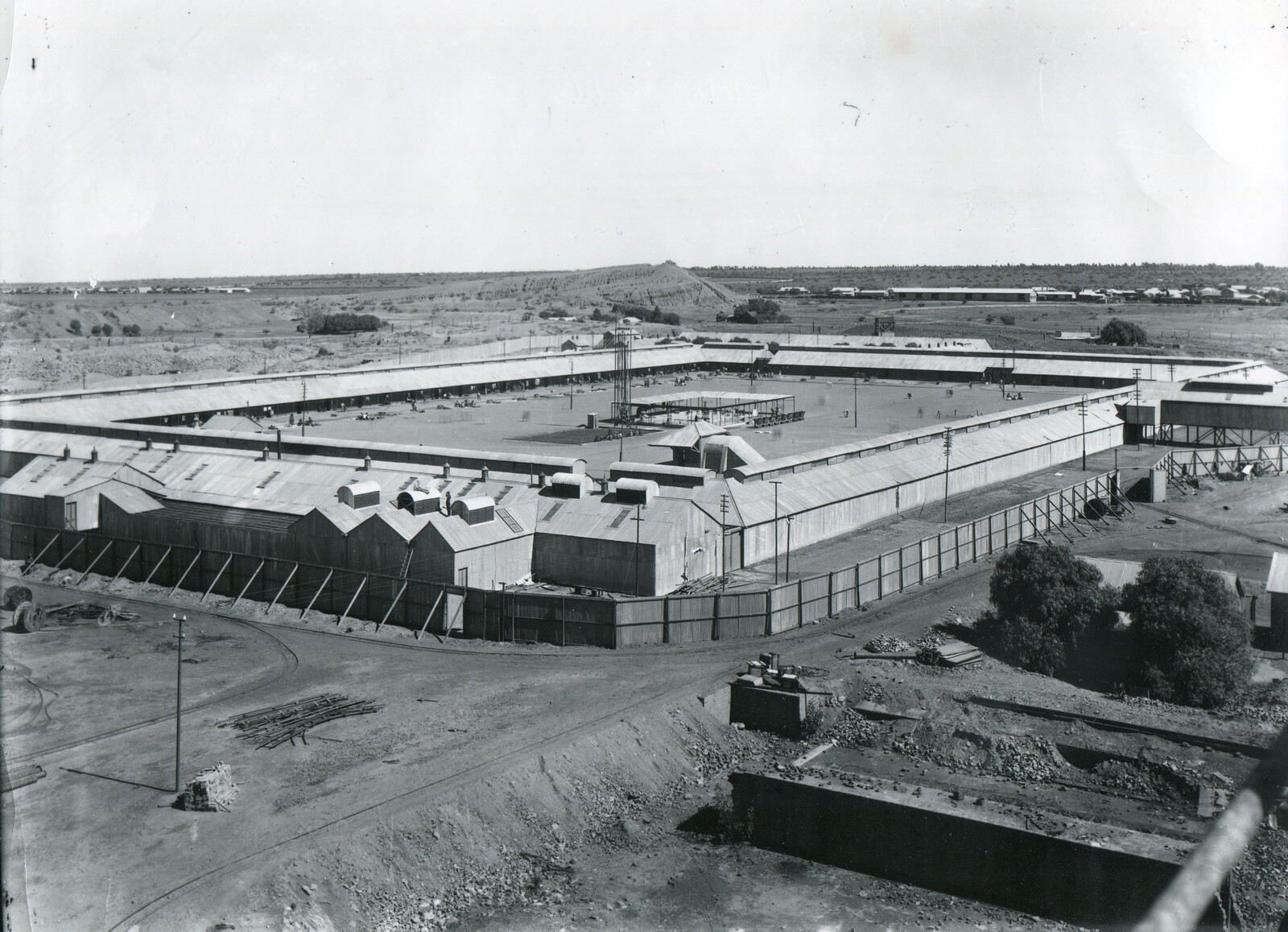

Garissa Lodge is widely known as the first “Somali mall.” A multi-story building hosting mixed-use shopping and residential accommodation, Somali malls define the built environment of Eastleigh, an area of Nairobi that was historically demarcated a “Somali” and “Asian” site in the 1948 Masterplan for Nairobi (1948).1 According to the “universal story” of Garissa Lodge, following an increase in the number of refugees arriving in Kenya from neighboring Somalia in the late 1980s, the small residential block began to be used for trade during the day and residential accommodation at night. In Nairobi in 2018, Mama Layla explained to me that, in the 1980s, “the Somalis started to come with their families and they used to sell their things on the bed in the day and sleep there at night. And then they grew and grew, so they expanded the building up to a second floor.”2 When it opened, it was the only one in the area, and catered specifically to “Africans,” meaning populations from northeastern Kenya, many of whom are ethnic Somalis or Kenyan Somalis.3 Although there are some variations in the narratives people tell about Garissa Lodge, certain details are common: it was owned by a blind Somali woman named Asha, it was a space for residential accommodation and trade, and it was the first of its kind.

Som City, Cape Town. Photo by author, 2014.

Som City

Although Garissa Lodge is widely known as the origin of Somali malls, I was first introduced to the idea and space of Somali malls at Som City (also known as Som Shopping Centre) in Cape Town, South Africa. Som City is a Somali mall established by Ahmed, a Somali refugee, near the train station in the northern suburb of Bellville in 2004. Ahmed says that the idea of a Somali mall with a lodge came to him from Eastleigh, which he passed through on the way to Cape Town. When this particular building in Bellville became available for rent in 2004, he got together with two friends and made an offer. They converted the ground and first floors into businesses, which today include a large restaurant, an internet café, and a laundry, among a series of shops run by women selling what are described as “Somali goods.” The upper three floors were turned into a residential lodge, offering shared short-term rented accommodation. In describing the process of starting the lodge, Ahmed notes the importance of this site as the first of its kind in the area. “You see people come in for buying, for the weekend, for Home Affairs documents. They were not having a place to sleep at that time.”4 Starting the lodge in Som City was therefore a response to a need for short-term lodging in the area for refugees from around the city.

When Ahmed first arrived in the city in 2000, he worked for four years as a street trader at Bellville station, an area that has increasingly become known as a safe space for migrants. He borrowed 1,000 Rand from extended family, bought a few items, and began hawking on the street, slowly expanding the scale of his trade. When the Som City building became vacant in 2004, rents were particularly low in the area. He and his two friends received help to pay the initial deposit from larger and more established Somali refugee-led businesses in the area. Ahmed noted the risk they took in starting the mall as it used up all their savings and put them in serious debt. At the time of speaking with him, however, the shops were all rented and the lodge was completely full three to four days a week. As a former office block, Som City is characterized by a series of small modular spaces. On my tour through the lodge, I was shown the various rooms, most of which were occupied by two to three beds. The bedrooms are fairly simple and unadorned spaces. Clothing and personal items were either stored on or under the beds. While walking through the building, Ahmed repeatedly referred back to his work as a street trader and noted that for the first two years of running the lodge, he lived in room 208. He saw himself in many of the new entrants.

2008

In 2008, urban areas across South Africa saw widespread xenophobic attacks that particularly targeted African migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees. The violence began in Alexandra township in Johannesburg on May 11, 2008, and within two weeks had spread across the country. Around sixty-two people were killed and 150,000 people displaced, many permanently.5 During the violence, many migrants and refugees from around the city and suburbs of Cape Town fled to Bellville, where Somali malls were increasingly seen as safe havens. Som City, along with neighboring lodges like Oriental Plaza, became “relief centers,” providing meals and free accommodation, supported by businesses in the malls.6 Most people stayed for two to three weeks, but some stayed for up to four months. Ahmed described the severity of the situation, and the need to provide free housing for those who could not afford alternative accommodation: “I could not tell the people just to go out and sleep outside. Especially that time, it was winter time, it was May, it was very cold outside. Everybody must come in, if they had money, they paid, if they did not, I said just stay. Some people lost everything.”7

The occupation of space and beds reflects migrant trading practices around Cape Town, the high levels of urban violence experienced more generally in South African cities, and the rhythm and regulation of being an asylum seeker or refugee in the city. Beyond the xenophobic violence of 2008, there have been sporadic yet frequent attacks targeting African migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers throughout South Africa. These lodges therefore operate in a liminal zone between temporary space of accommodation and safe and stable refuge from ongoing violence. As Parin Dossa and Jelena Golubovic point out, “interstitial locations should not be excluded from analyses of home-making simply because they are temporary.”8 In a different context, Dominique Malaquais similarly notes that, for many African migrants, “the plan to move on … is often several years old.”9 In the case of Somali refugees, multiple and forced displacement characterizes protracted refugee situations across generations. In these lodges, not only does the labor of home-making become visible, but also the quotidian processes of unmaking homes faced by refugees.

Outside moments of crisis, the lodges demonstrate the continued and everyday precarity of home. In the stories told of renting rooms, of saving for remittances or future prospects, the narratives that circulate emphasize an ambivalence about them as spaces of refuge and home in the wake of displacement, and signal the hope for another kind of communal future. AbdouMaliq Simone suggests that, in response to systemic structural violence, a kind of urban “politics of peripheral care” emerges by and for marginalized populations with limited provisions.10 These lodges seem to act in a similar manner, enabling a certain level of endurance against violence as part of a longer string of similar displacements through the provision of an emergency home in the absence of state support. The role of the lodges as sites of emergency housing in Bellville in 2008 is one of the reasons given for the rise in the number of lodges within Somali malls, and for the growth of the area as a whole.

Transnational infrastructures

Lodges and the spatial practices that occur within them are closely tied to their particular locations. But perhaps more than responding to the particularities of life in Cape Town, these lodges respond to populations in flux across the continent of Africa. All of these markets have formed in the wake of state collapse in Somalia and a large population that has become mobile by force. Ahmed’s idea to start a lodge originated in his brief stay in Eastleigh. His story has significant similarities with the stories told of other lodges and the proprietors who started them. In the case of both Mama Aisha, the founder of Garissa Lodge, and Ahmed, the lodge is narrated as ambivalently located between personal profit, the precarious present, and a potentially profitable and prosperous future. Ahmed’s description of Som City clearly positions it in relation to Eastleigh and Garissa Lodge. He therefore narrates his own experience as part of a “universal story,” situating Som City within a lineage of informal malls and lodges across the continent. The repetition of stories about Garissa Lodge and similar spaces is as much about the particular sites they refer to, which are very real, and the narratives of hope for physical and social mobility they suggest in their circulation. As such, these narratives offer us a subaltern form of spatial knowledge.

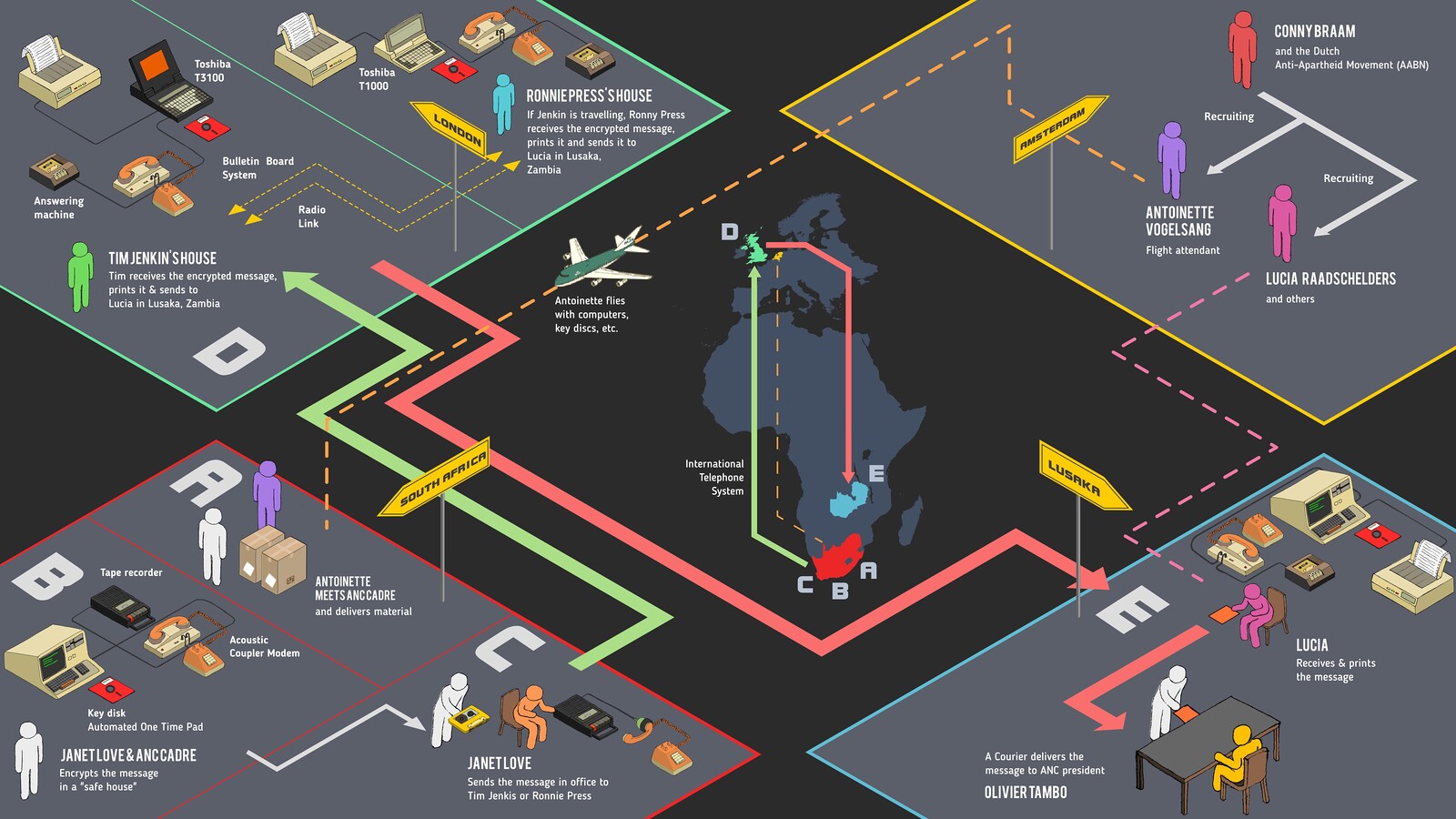

In recounting his experience of attempting to travel to South Africa, Mahmoud, a Somali refugee, described a motel of sorts in Lusaka, Zambia, run by a woman known as “Mama Asha.” He said of her, “this lady would allow the travelling Somalis and Ethiopians to stay at her home. She also owned a small motel there. If someone could afford to pay her for her hospitality, she would ask for payment. If someone did not have money to pay her, she would allow him or her to stay there free of charge.”11 This description closely echoes what was told to me in Cape Town and Nairobi, where the emergence of lodges as profitable businesses does not come at the expense of offering refuge and hospitality for those who cannot pay. The area where “Mama Asha’s Motel” was located was described as similar to Eastleigh. Mama Asha was a Somali refugee herself, and “everybody knew her.” Mama Asha’s “establishment” was part of a trajectory for Mahmoud that included Dhobley and Liboi refugee camps, on either side of the Kenya-Somalia border, and Dar-es-Salaam in Tanzania. These refugee infrastructures connect specific sites that exceed national boundaries.

For Homi Bhabha, stories have performative potential and telling them can be understood as a transgressive tactic for those without formal power. Bhabha describes the importance of these stories and their circulation through Ranajit Guha’s analysis of a peasant insurgency in India and the “chapati story” in relation to the 1857 uprising. In the chapati story, rumors of a planned uprising against the British were supposedly spread along with the distribution of chapatis, or flat Indian breads, that were hand-delivered to villages. As Bhabha explains, it is not known whether details of the uprising actually spread with the chapatis or not, yet this is irrelevant, as the circulation of the chapati story is very real and has a wide reach. He points out that the circulation of the story or rumor established a sense of solidarity among the colonized and created widespread unease amongst British colonizers. Bhabha therefore argues that the story itself holds a kind of performative power as it circulates in time and space with very real material effects.12 Although operating in a very different context, these various lodges offering refuge in times of need along with the stories that circulate about them can be understood as a form of infrastructure. They are constructed and circulated around and within Somali malls as more than improvised or ad hoc stories. They both perform and suggest a particular kind of spatiality associated with distinct spaces that are known to those who need them.

Black Infrastructures

Taking seriously the narrations and narratives of refugees themselves is a methodological and epistemological position aimed at recognizing forms of subaltern spatial knowledge and creating a radically different archive. Following Katherine McKittrick, understanding these networks as black infrastructures recognizes the way that colonial and racial violences “shape, but do not wholly define, black worlds.”13 For AbdouMaliq Simone, Black Urbanism similarly has the potential to draw the lives and spaces of displaced African populations out of the periphery.14 Recognizing networks of narration and physical sites as Black infrastructures enables an appreciation of the centrality of these spaces to the marginalized populations who inhabit them, while also acknowledging ongoing and durable precarity. This is an infrastructure of care that enables us to understand a “black sense of space” beyond the repeated suffering and violation of the black body. Black infrastructure is an idea as much as a physical network enabling the circulation of goods, people, and narrations.

The lodges and associated Somali malls might be the first point of entry for new arrivals; a temporary space for those passing through or the site for ongoing life and care. They represent spaces that are not reducible to or exhausted by mechanisms of control and violence.15 Beyond offering a temporary home, lodges exist in relation to each other. They symbolize refuge, yet are simultaneously material spaces tied into histories of colonial planning, refugee policies, and the ongoing racialization of migration. Within these spaces, refugee populations negotiate the deep, unequal terrains of global capital and global mobility while remaining active within a precarious politics of care.16 Displaced populations assemble new spatial and material nodes as a way of overcoming formal exclusion, and these black infrastructures constitute material and narrative spaces of refusal and recognition. They are sites of resistance against quiet and dispersed everyday suffering, offering instead spaces of sociability and support that extend across national borders.

The refugee is often discussed at the scale of the nation or continent and in relation to the physical border. Yet the daily lives and lived experiences of migrants and refugees are framed by the places they find shelter, work, and home: the spaces from which they negotiate everyday exclusion and displacement. While the physicality of the border and the practice of crossing might be considered a primary infrastructure of mobility and immobility, the stories told beyond the physical border evince a more complex view of the refugee and their own spatialities. It is in the small interiors of everyday spaces that daily lives are made livable. Looking closely and speaking to intimate and small-scale interiors is an example of what Anna Tsing calls “looking around rather than ahead”: a means of recognizing practices of care and refusal.17

Care is overwhelmingly understood in relation to female social reproduction; as such, it is both undervalued and highly gendered. Yet the intimate spaces of daily life can be understood as infrastructures, enabling livelihoods in the context of ongoing precarity. The interior offers an infrastructure for survival and care, made by refugees themselves, against a hostile world beyond. This is not to suggest that it is possible to separate practices of care from systemic inequality and existing power structures, but rather is a way to understand how people forge lives in the contexts of precarity. Somali malls and similar spaces offer vital infrastructures for “enduring precarious worlds.”18 Adopting a feminist ethics of care is therefore both a set of strategies for studying space and an approach for listening to how marginalized populations live with precarity and in entangled spatial histories. Listening is key to recognizing the transgressive role of narrative for those in subaltern positions, where the story contains both the idea and the spatial model. The repeated refrain acts as a form of spatial knowledge to reinforce, construct, and engender particular kinds of spaces. They offer networks of support and possibility despite remaining inherently precarious.

The area continues to be a contested space in the city, and can be read within a wider urban ecology of exclusion. Wangui Kimari, “The story of a pump: Life, death and afterlives within an urban planning of ‘divide and rule’ in Nairobi, Kenya,” Urban Geography 42, no. 2 (2019): 1–20.

Interview with Mama Layla, 2018.

Interview with Mohammed, 2018; interview with Mama Layla, 2018.

Interview with Ahmed, 2015.

Aurelia Segatti and Loren B. Landau, eds., Contemporary Migration to South Africa: A Regional Development Issue (Washington, D.C.: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank, 2011).

Interview with John, 2014; interview with Patel, 2014. See also Zara Nicholson, “Somalis Find a Safe Haven in Bellville,” IOL, May 11, 2011, ➝.

Interview with Ahmed, 2015.

Parin Dossa and Jelena Golubovic, “Reimagining Home in the Wake of Displacement,” Studies in Social Justice 13, no. 1 (2019): 171–186, 173.

Dominique Malaquais, “Douala/Johannesburg/New York: Cityscapes Imagined,” in Cities in Contemporary Africa, eds. Martin J. Murray and Garth A. Myers (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2006), 31–52.

AbdouMaliq Simone, Improvised Lives: Rhythms of Endurance in an Urban South (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018), 25.

English translation of Somali recording, July 13, 2014, Minnesota Oral History Project.

Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 289.

Katherine McKittrick, “On Plantations, Prisons, and a Black Sense of Place,” Social & Cultural Geography 12, no. 8 (2011): 947–963.

AbdouMaliq Simone, “Reclaiming Black Urbanism,” in City Life from Jakarta to Dakar: Movement at the Crossroads (New York: Routledge, 2010), 263–332.

Anooradha Siddiqi argues that taking seriously the refugee’s concerns and problematics requires an epistemic shift, while Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh points to the importance of understanding the refugee as not only and always a passive subject. See: Anooradha Siddiqi, “The University and the Camp,” Ardeth 6 (2020): 137–151; Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, “Introduction,” in Refuge in a Moving World (London: University College London Press, 2020), 1–19.

See: Francis B. Nyamnjoh, “Globalisation, Boundaries and Livelihoods: Perspectives on Africa,” Identity Culture and Politics 5, nos. 1–2 (2004): 37–59, 44; Simone, Improvised Lives.

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 22.

Hi‘ilei Julia Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart and Tamara Kneese, “Radical Care: Survival Strategies for Uncertain Times,” Social Text 142 (2020): 1–16, 2.

Coloniality of Infrastructure is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, Critical Urbanisms at the University of Basel, and the African Centre for Cities of the University of Cape Town.