I

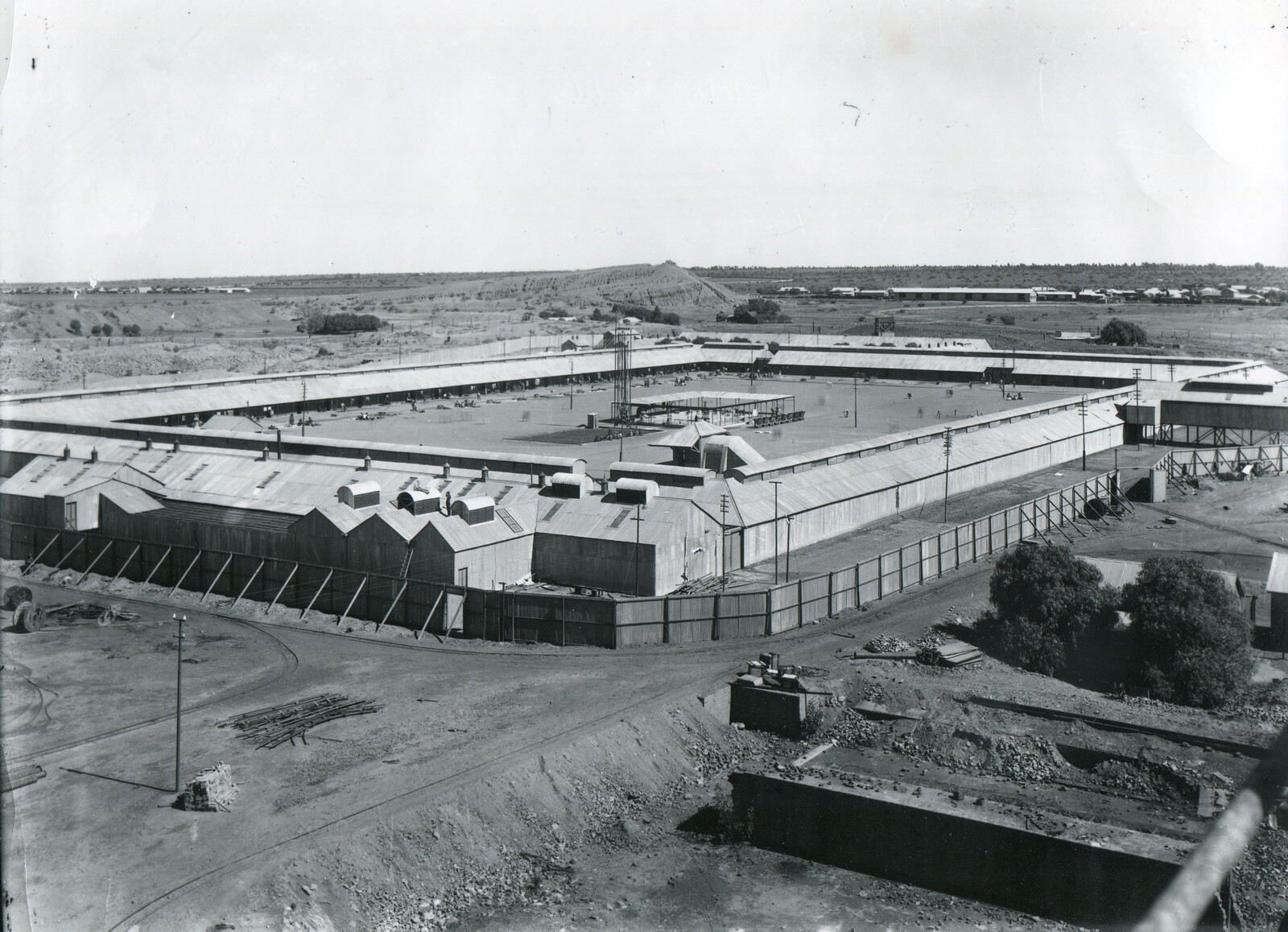

The Italian colonization of Libya began in 1911 and escalated under fascist rule, eventually leading to the brutal repression of the armed resistance led by Omar al-Mukthar (1922–1931) and the internment of over 100,000 people of indigenous origin in concentration camps.1 This persecution lasted until 1943, when Italy lost control of Libya following a series of military defeats in World War II. In 1951, newly independent Libya issued the first request for reparations to Italy, seeking a total of 100 million Libyan dinars. It was only after Muammar al Qaddafi overthrew the monarchy and brought about the revolution in 1969, however, that the request for reparations intensified. In 1970, Qaddafi expelled 20,000 Italian colonists who had remained in Libya after the war. Italy was then pushed to commit to wider reparations, including the construction of a hospital in Benghazi; the removal of landmines left by the Italian army during its retreat after the defeat at El Alamein (Egypt); the restitution of looted archeological artefacts, such as the Venus of Cyrene (which had been stolen by the Italians in 1915); and the return of the remains of Libyan rebels exiled to Italian islands in the early years of Italian colonization.

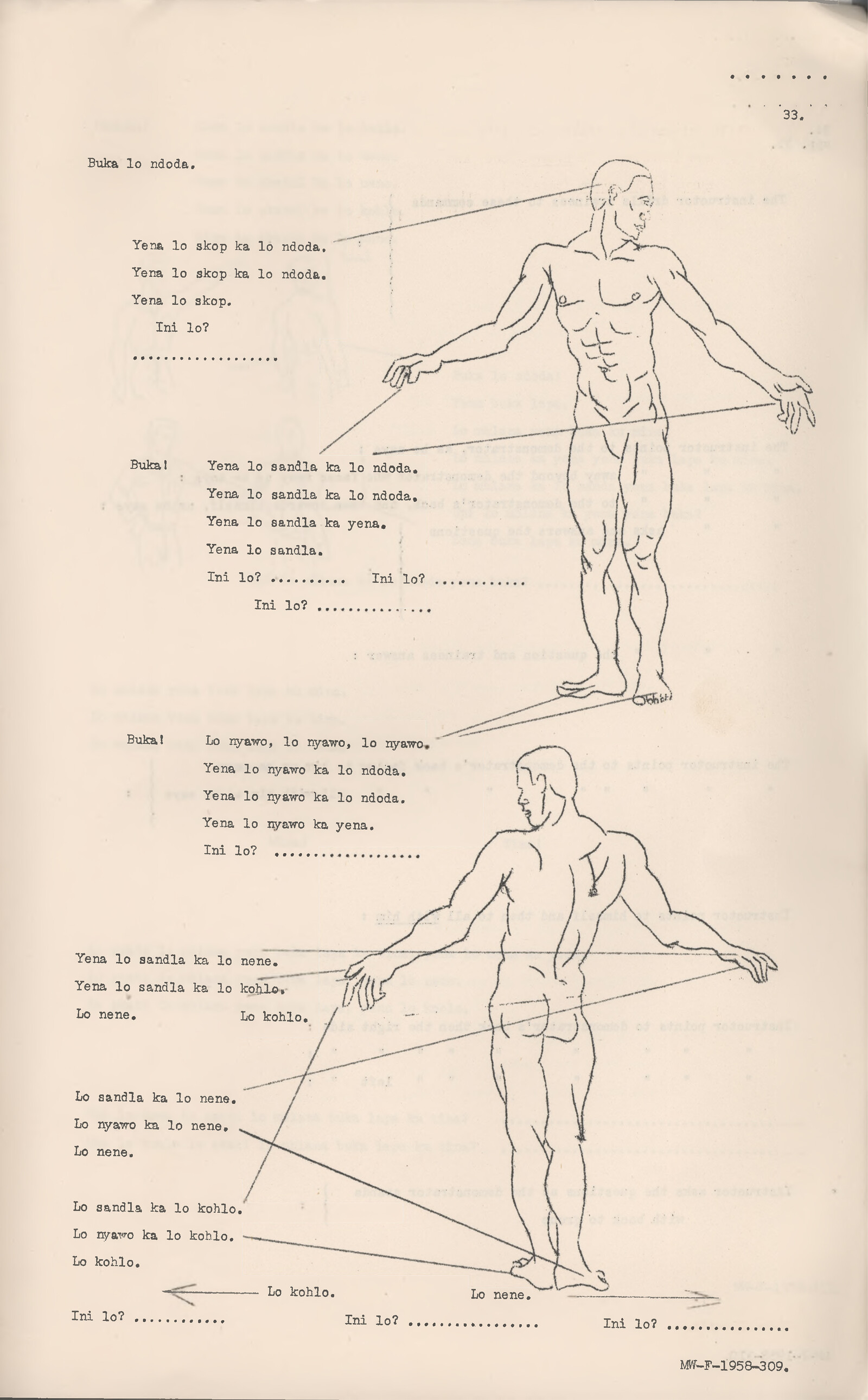

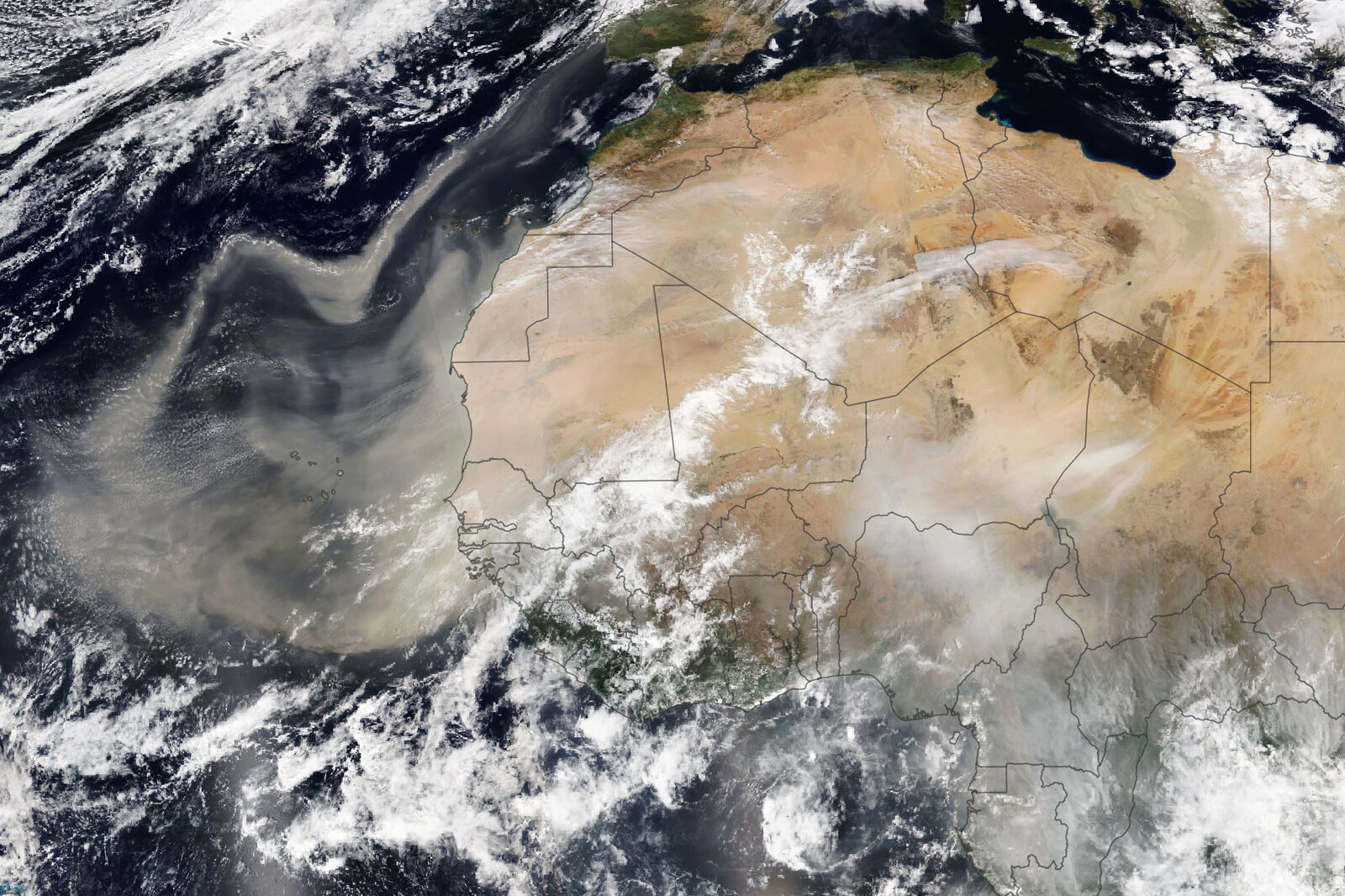

Qaddafi understood that reparations should revolve around infrastructural development. As soon as he came to power, his demand to replace the coastal highway that Mussolini inaugurated in 1937, a 1,000-kilometer stretch of asphalt running between the Tunisian and Egyptian borders, defined Libya’s strategy in its fight for reparations from the Italian state. Originally named the Strada Litoranea Libica, the Italian motorway linked coastal urban areas, highlighting Italy’s geopolitical ambitions in the Mediterranean basin and sealing the unity of a newly-created Libya (which had been divided into the regions of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica under Ottoman rule). The highway thus “made space” for new Italian settlers, enabling an infrastructural sprawl across the Sahara that linked together rural settlements, military outposts, wells, pipelines, aqueducts, cisterns, and fields. The racial principles underpinning “demographic colonization”—the Italian mode of settler colonialism—were the foundation of a modernizing and civilizational project that intended to impose racialized labor regimes, separate the natives from the conquerors, and crush indigenous nomadism.

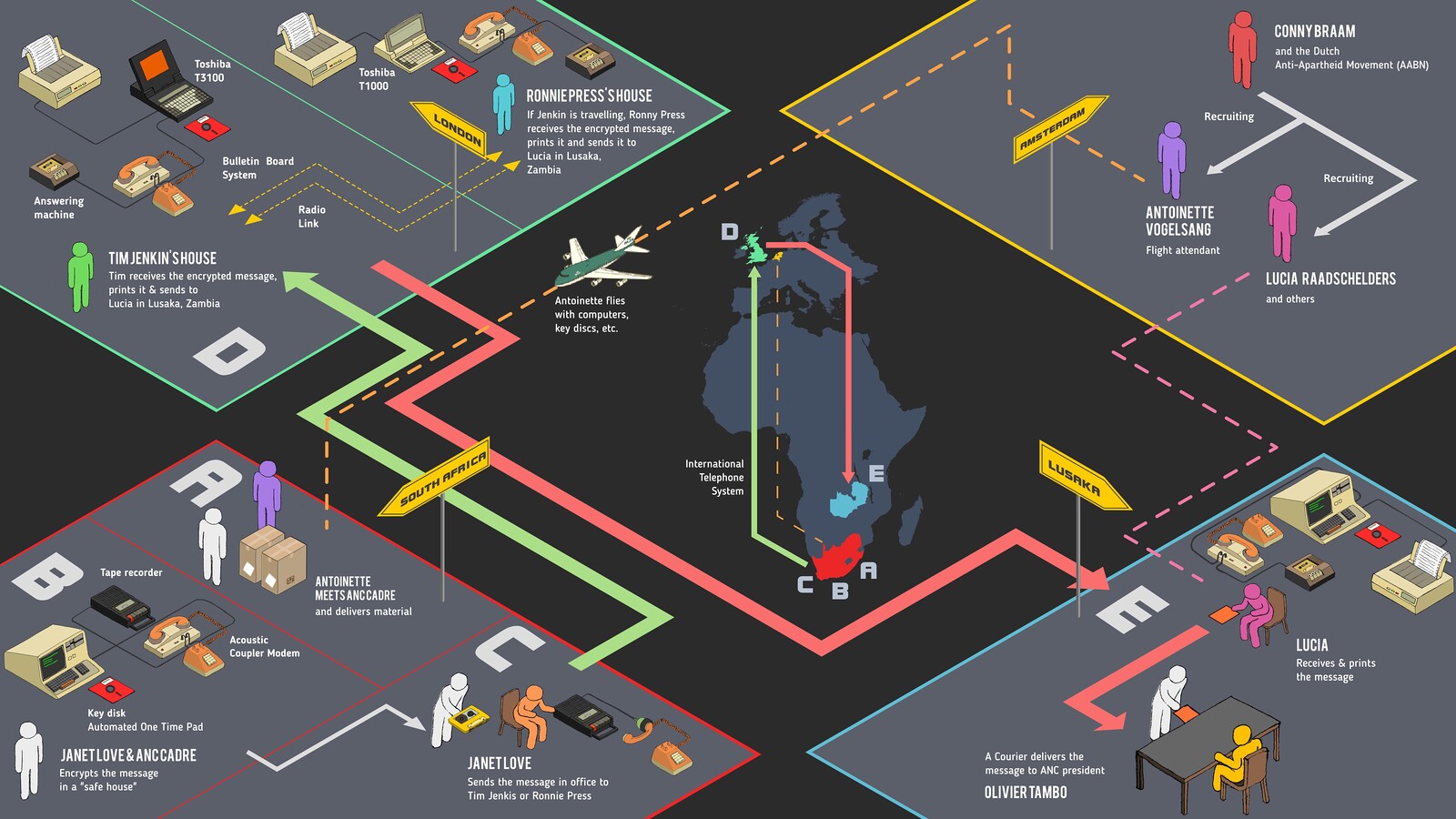

Despite Qaddafi’s anticolonial rhetoric and actions, Italian companies became increasingly influential in independent Libya. Throughout the 1970s, for instance, the Italian oil and gas company ENI (Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi) retained a key role in the country’s energy industry, and eventually became the main bridge between Tripoli and Rome. This lasted until the early 2000s, when Italy made a provisional gesture towards reparations on the condition that Libya would help control and prevent migrant flows across Libya’s southern land border and the Mediterranean. In 2008, Italy and Libya reached a historic agreement with the Treaty of Friendship, Partnership, and Cooperation. Also known as the Friendship Pact, the deal was shaped around a compensation scheme including development and investment programs totaling five billion US dollars, as well as funding for the long-sought after project of a new motorway.

While the Friendship Pact formally brought claims for reparations for colonial crimes to a close, it effectively established the Mediterranean as a policed and surveilled frontier, thus paving the way for new humanitarian crimes to be committed. Under the façade of reparations, the Pact eventually subverted the essence of posthumous justice. This all took place concurrently with Qaddafi backing the African World Reparations and Repatriation Truth Commission, which argued Africa should be given a permanent seat on the UN Security Council and $777 trillion US dollars in compensation for slavery and colonialism.

The Friendship Pact was unilaterally suspended by Italy as the Arab uprisings spread to Libya in February 2011, and subsequent NATO attacks led to the toppling and death of Qaddafi. Since then, successive Italian and interim Libyan governments have tried repeatedly to keep the Litoranea project alive. In 2013, the Italian industrial group Salini-Impregilo (today Webuild SpA) successfully tendered to build the first section of the motorway, the Ras Ejdyer–Emssad Expressway, running 400 kilometers from the city of Al Marj to Emsaad on the Egyptian border. In early 2019, Libyan media reported that the Italian ambassador to Libya and the Libyan transport ministry had been discussing a possible date to start works, pending guarantees of security for Italian contractors. Yet amid this continued focus on infrastructure, the core of postcolonial reparation processes—namely, the question of posthumous justice for victims and descendants of Italian colonial crimes—has been sidelined.

Omo river, Gibe III Dam in Wolayita, Ethiopia. Photo by Mimi Abebayehu, 2016.

II

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, Ethiopia was the first African nation to attempt to hold post-fascist Italy accountable for its occupation (1936–1941) and crimes by calling for reparations. After the 1947 Paris Peace Treaties declared the formal end to WWII, Ethiopia cited article 37, which stipulated the restitution of works of art and objects of archaeological, religious, and historical value purloined during the fascist occupation. Most iconic was the stele of Aksum, an ancient funerary monument and symbol of Ethiopian civilization, which was looted by fascist troops in 1938 and re-erected in Rome. After Ethiopia was denied membership of the United Nations War Crimes Commission, however, Italian crimes were never prosecuted, and the stele stayed captive in Rome.

In the decades following the Italian fascist occupation, Ethiopia underwent radical political transformations. In 1974, Haile Selassie and dynastic rule gave way to a Soviet-inspired military junta calling itself the Derg. Its leader, Mengistu Haile Mariam, wanted to wean Ethiopians from the iconography of monarchy and feudalism, and diverted the popular focus away from demands for Italy to return the stele. Only after the fall of the Derg did this aim reemerge as a priority, paving the way for an Italo-Ethiopian agreement in 2002 that led to the restitution of the stele.

The return of the stele to Aksum was the impetus for a more a wide-reaching act of reparation, which included the cancellation of Ethiopian debt and Italian participation in rural and hydropower development projects. One outcome of this was an Italian-Ethiopian loan agreement of €220 million euros for the Gilgel Gibe II hydropower project in the Omo River region in southern Ethiopia. To date, Gibe Dams I, II, and III have been built, while Dam IV is under construction and Dam V is being planned and reviewed by other international investors. Together, they comprise a cascade of structures along the Omo River designed for floodwater regulation and cheap electricity generation, all revolving around the management of land for extensive cultivation and food production.2 Four years after the 2002 agreement, the state-owned company Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation awarded—with no competition—the same construction company, Salini-Impregilo, a US$1.7-billion engineering and construction contract for Gilgel Gibe III. Then, in 2016, Salini was awarded another contract to extend the project to Dam IV.

Hydropower remains central to Ethiopia’s development strategy. It is also in line with Italy’s historic and colonial involvement in Ethiopia. For instance, during the occupation, fascist occupiers started constructing the Aba Samuel Dam on the Akaki River, and, in 1957, dam infrastructure was included in an initial reparation initiative in which Italy financed the construction of the Koka Dam in Oromia, which was then contracted to Italian companies.3 It is perhaps no surprise, then, that in the aftermath of the 2002 agreement’s ratification, Italian officials invoked the colonial argument of “backwardness” to describe how the dam would give millions of Ethiopian life-enhancing access to electricity.

Throughout many historical phases—Italian occupation, Haile Selassie’s state-building, the Derg’s modernist planning, and the infrastructure boom of recent decades—the ideology of modernization has propelled vast dispossession of indigenous populations. Land demarcated for dam projects, from the Awash Valley in the 1950s to the Omo Valley today, has been cyclically and cynically described as “unoccupied” and “underutilized,” while the inhabitants of those lands have been stigmatized as “backward,” “primitive,” and hence “disposable,” that is, suitable for resettlement.4 This is evident in the Gilgel Gibe dam project. Since 2015, the Omo River’s annual flood has stopped, which has placed entire communities at risk of food insecurity and conflict. The project’s developmental chain also threatens to exacerbate displacement and internal migration from north to south, intensifying inter-ethnic conflict. Furthermore, people of the region may be subjected to dependence on wage labor as well as social exclusion after undergoing expropriation and “civilization” by the Ethiopian state and Italian contractors.5

Under the pretense of closing a guilty chapter in Italian history by returning the stele to Aksum, the reparations process has again forced the wider question of postcolonial justice. As internal racialized inequalities and injustices grow, the modernizing ethos intrinsic to the Italo-Ethiopian agreement preserves separation between “modern” and “traditional.”

The Lion of Judah at the top of the fourteen steps fascist monument, Addis Ababa. Photo by Luca Capuano/Camilla Casadei Maldini in Nuovo Fiore, ISIA Urbino, 2020.

III

Despite their differences, the deals struck with Libya and Ethiopia were both intended to “wash out” colonial crimes and responsibilities via infrastructural development and state-building projects. In both instances, the subject of reparations was wedded to an uneven system of mobility: the hypermobility of commodities, materials, and capital as opposed to the immobility and displaceability of people in the ex-colonial world. They block people from fleeing the post-colony and forcibly “villagize” indigenous populations. The promise of infrastructure was used to legitimize a failed model of reparation that perpetuates the same injustices it was meant to fix.

For decades, this status quo has been challenged by those calling for new trajectories beyond economic reparation programs grounded solely on monetary compensation. Should a process of reparation exist solely within the sphere of bilateral agreements between governments and nation-states? In what other forms could reparations be imagined and re-arranged? From the histories and testimonies of the anti-slavery struggles of Afro-Caribbeans, Afro-Americans, and indigenous North Americans, we have learned that the struggle for justice must lead to epistemic reorganization.6 Having to deal with collective experiences of radical loss and broken existences, post-slavery and post-genocide communities have posed the question of reparation as part of the practice of “repair.”

Such repair requires a revolution of consciousness, an active process that aims to fix collective existences marked by centuries of race-based and structural violence.7 The reparation of such history cannot be reduced to mere “compensation” or “return” of looted objects. Indeed, it must embrace the recollection of historical traces, heritage-making, and the right to regenerate historical narratives. Christina Sharpe writes that, in the wake of slavery, “we yet reimagine and transform spaces for and practices of an ethics of care (as in repair, maintenance, attention), an ethics of seeing, and of being in wake as consciousness.”8 Achille Mbembe similarly calls repair a relational experience that can reconstitute a “lost” self towards freedom and self-determination.9 This process does not rely on the presence of the perpetrator, or even the state, but instead calls for epistemic justice and freedom from the yoke of civilizational and developmentalist narratives.

IV

During a trip to Addis Ababa in 2019, I participated in the symposium “Decolonizing Architecture” at The Urban Center, a collaborative space for active citizenship, debate, and co-work in Addis.10 The event took place during the opening of an exhibition curated by Rahel Shawl and her team from RAAS Architects, which showcased the legacy of Italian colonial architectural and infrastructural development built in Addis Ababa during the fascist occupation. Coming on the heels of the Asmara Heritage project, which led to the nomination of Eritrea’s capital as a UNESCO heritage site in 2018, the exhibition showed how Addis’s fascist colonial architecture is at risk of decaying and being overshadowed by the encroaching urban transformation that, since the era of the Derg, has symbolized a seemingly unstoppable path of modernization.

Architectural conservator Abel Assefa, who contributed to the exhibition, has explored infrastructural sprawl in Addis and the impact of massive infrastructure developments on heritage.11 Assefa notes, for example, that several monuments and statues are being damaged and removed from public spaces, including the removal of the 1941 statue of Abune Petros—the Ethiopian Orthodox cleric who opposed the Italians and was executed in 1936 by the occupation forces—to make space for a light-rail transit tunnel at Menelik Square. Meanwhile, new railway planning led to the 2014 transformation of Maichew Square (also renamed Mexico Square to honor Mexico’s refusal to recognize the Italian occupation in 1936). In the process, the public monument celebrating the battle of Maichew—the beginning of the Ethiopian resistance movement—was inadvertently destroyed.12 Such interventions, many irreversible, imperil the heritage of a city established only fifty years before being seized by Italy.

Rahel Shawl and her team from RAAS Architects responded to this issue by documenting and reactivating a network of existing built heritage—albeit one threatened by decay, abandonment, and forgetting. Beyond the role of infrastructure as an economic boon or a form of reparations from former occupiers, her process heralds an act of repair that is not predicated on creating something new, but on the contrary, advocates for an epistemic reorganization of the built environment. In this perspective, the architecture of the occupation provides an entry point to the complex and turbulent last seven decades of Ethiopian history, challenging the narratives of modernization. It triggers the need to desegregate this heritage from the tentacles of infrastructural development that now constitute a threat to the historic identity of Addis.

This impetus to resist violent modernization arguably comes from Ethiopia’s strong anti-colonial tradition and its desire to situate its heritage and history against Italian fascist colonialism. It traces back to the years immediately following liberation, when Ethiopian people had to resolve the question of what to do with prominent fascist “leftovers,” whether monuments, public buildings, or the strands of eucalypts along Italian-built highways. Still standing in front of Addis Ababa University’s Institute of Ethiopian Studies, for instance, is a staircase of fourteen steps built in 1936 (in front of what was then the royal palace) to celebrate the fourteen years since Mussolini came to power in 1922. When Ethiopia was liberated in 1941, the monument was not demolished, but preserved in an altered form: a statue of the Lion of Judah was installed on the last step, memorializing Ethiopia’s victory over the fascist occupier. It was an affirmative act of repair, where the original monument could only be preserved through an intervention that would, at least symbolically, fix what fascism had broken.

Repair comes after destruction. The staircase, originally built like a crude concrete edifice, was designed to symbolize an “escalator” of fascism ascending to imperial glory. Today it inspires us to imagine a less bleak future for infrastructure itself, and is proof that, after malfunctioning, infrastructure can still be activated in the lasting fight for reparative justice.

Ali Abdullatif Ahmida, Forgotten Voices. Power and Agency in Colonial and Postcolonial Libya (New York and London: Routledge, 2005).

Jon Abbink, “Dam Controversies: Contested Governance and Developmental Discourse on the Ethiopian Omo River Dam,” Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale 20, no. 2 (2012): 125–144.

Claudia Carr, “The Persistent Paradigm for ‘Modernizing’ River Basins: Institutions and Policies in Ethiopia,” in River Basin Development and Human Rights in Eastern Africa: A Policy Crossroads (Cham: Springer, 2017).

Asebe Regassa and Benedikt Korf, “Post-imperial statecraft: high modernism and the politics of land dispossession in Ethiopia’s pastoral frontier,” Journal of Eastern African Studies 12, no. 4 (2018): 613–631.

David Turton, “The downstream impact,” presented at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London, October 11, 2010.

Robin D.G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002).

Mari J. Matsuda, “Looking to the Bottom: Critical Legal Studies and Reparations,” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 22 (1987): 323–399.

Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 131.

David Theo Goldberg, “‘The Reason of Unreason’: Achille Mbembe and David Theo Goldberg in conversation about Critique of Black Reason,” Theory, Culture and Society 35, nos. 7–8 (2018): 205–222. See also Robert Westley, “Many Billions Gone: Is It Time to Reconsider the Case for Black Reparations?” Third World Law Journal 19, no. 1 (1998): 429–476.

Together with Alessandro Petti, Ana Naomi de Sousa, Fasil Ghiorghis, and others.

Abel Assefa, “Challenges and Advances on Cultural Heritage Management of Public Monuments and Statues in Addis Ababa,” presented at the 10th International Conference of the History of Arts and Architecture in Ethiopia (ICHAAE), Mekelle University, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2015.

Assefa, “Challenges and Advances on Cultural Heritage Management.”

Coloniality of Infrastructure is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, Critical Urbanisms at the University of Basel, and the African Centre for Cities of the University of Cape Town.