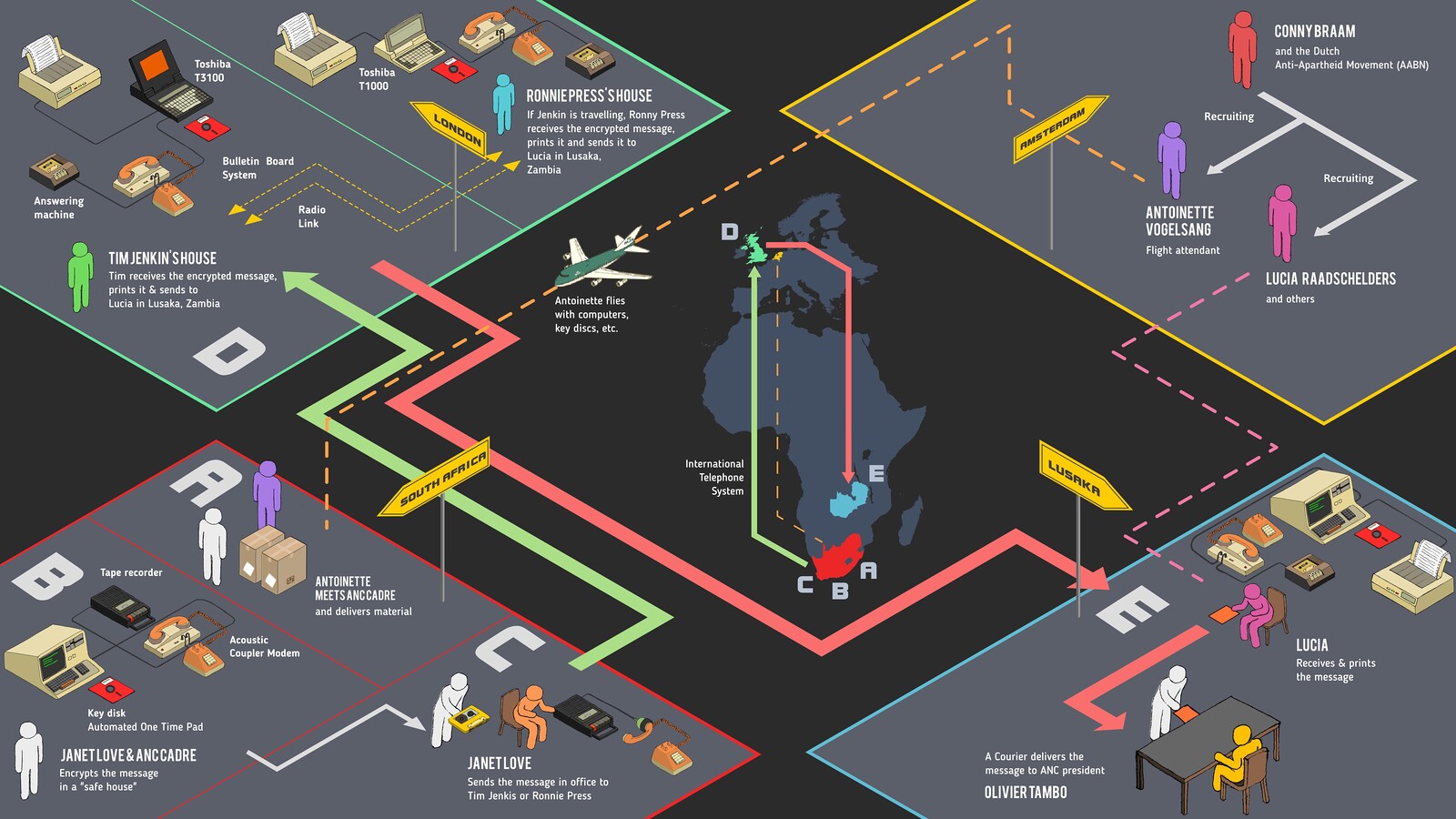

It is July 1990. Janet Love, an uMkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation,” abbreviated MK) commander, sits by herself in an office in Johannesburg she had lock-picked her way into, holding a small tape player/recorder next to a landline phone. Earlier that morning, she had typed a message on a laptop located in a safe house maintained by an anti-apartheid Canadian couple, using an encrypted floppy disk that was smuggled a few months prior by a Dutch flight attendant named Antoinette, who doubled as an anti-apartheid operative. Once the message was typed out, she encrypted it before passing it through the computer’s serial port to an acoustic coupler modem. The digital data was thus converted to sound, which she captured on a small cassette tape recorder—the same device she now holds up to the telephone receiver.

On the other end, in London, the phone is connected to a special answering machine configured by two freedom fighters, Tim Jenkin and Ronnie Press, with the express purpose of receiving just such a message from South Africa. Working on his computer, Jenkin plays the audio message back through an acoustic modem similar to the one used by Love, converting its analog signal back to digital, thus rendering it back into data that he can decipher using a floppy disk matching the one used by Love. At the end of this process, a simple string of plaintext appears on Jenkin’s computer screen:

Very Urgent, Very Urgent, Very Urgent. Please pass this to Lusaka immediately. This morning it looks like Paula has been taken by the police. Big problems with the communications because it seems that Paula was in the habit of carrying around the program disk and the files.1

After reading the message, Jenkin replied promptly:

Oh dear! It will indeed be serious if the enemy gets the disk as then they will be able to undo all previous messages sent using it. Dear me. What are we going to do?

Jenkin immediately forwards the message, repeating the encryption process, to Lusaka, where two Dutch anti-apartheid activists, Lucia and Ineke, receive the enciphered message, decipher it, and print it out in hard copy. A courier then picks it up and takes it to senior African National Congress (ANC) members. Through a communication system connecting the continents of Africa, Europe, and North America, Jenkin forwards the message to nodes in Zimbabwe, the Netherlands, and Canada, informing them of the critical situation and asking them to stay alert for further messages.2

This communication infrastructure was developed by the ANC Technical Committee during the final years of the South African liberation struggle. The system was fully operational from 1988 until 1992, and it was used throughout the major cities in South Africa (Cape Town, Durban, and Johannesburg), as well as Amsterdam (the Netherlands), York (Great Britain), Tallcree First Nation (Alberta, Canada), and Harare (Zimbabwe). It was also tested in Paris, but never operationalized. Long before its operationalization, however, the dream of secret and rapid long-distance communication had been brewing in the mind of South African freedom fighters.

Emergence of a Technical Committee

One of the earliest written mentions of a Technical Committee in official ANC literature can be found in a Mayibuye (“Take Back Our Country”) Operation document. The document was discovered by apartheid police on July 11, 1963, leading to the arrest of the leaders of the ANC, MK (the ANC’s armed wing), and the South African Communist Party (SACP). The arrests took place one-and-a-half years after the beginning of the sabotage campaign by the ANC, MK, and SACP, and following the declaration of armed struggle. The Mayibuye Operation set out a course of action to reclaim South Africa from white supremacist domination and to put in place a revolutionary democratic country based on the 1955 Freedom Charter. The document stated that the Technical and Supply Committee (as it was known back then) was to be responsible for manufacturing and building stocks of arms and explosives, organizing the storage of supplies and training, and acquiring equipment to facilitate communication.3 Leadership had planned to discuss the document on the day of their arrest, but were cut short by the apartheid regime’s intervention. Joe Slovo, one of the earliest members of MK, had fled South Africa with a copy of the Mayibuye document one month before, and was tasked with consulting about the plan with Oliver Tambo, the exiled president of the ANC, and other members of the external leadership.4

The arrest of the leaders was a terrible blow to the national liberation struggle, and pushed freedom fighters out of South Africa in what would be referred to as the “external mission.”5 The Technical Committee—made up of South Africans, amateur or trained scientists, and technologists initially based in South Africa—continued to exist in exile in the UK, where its members had relocated to manufacture technical and communication equipment and artifacts for the struggle. The Technical Committee’s approach was influenced by major Cold War events, such as the launch of Sputnik 1, technological and scientific developments in Russia and China, and the writings of Russian and Irish scientists, among others.6 In opposition to the Republic of South Africa’s investment in science and technology for the purposes of domination and oppression, based on a philosophy of scientific or biological racism and eugenics, the Technical Committee believed that devices and machines could be used for the benefit of people’s liberation.

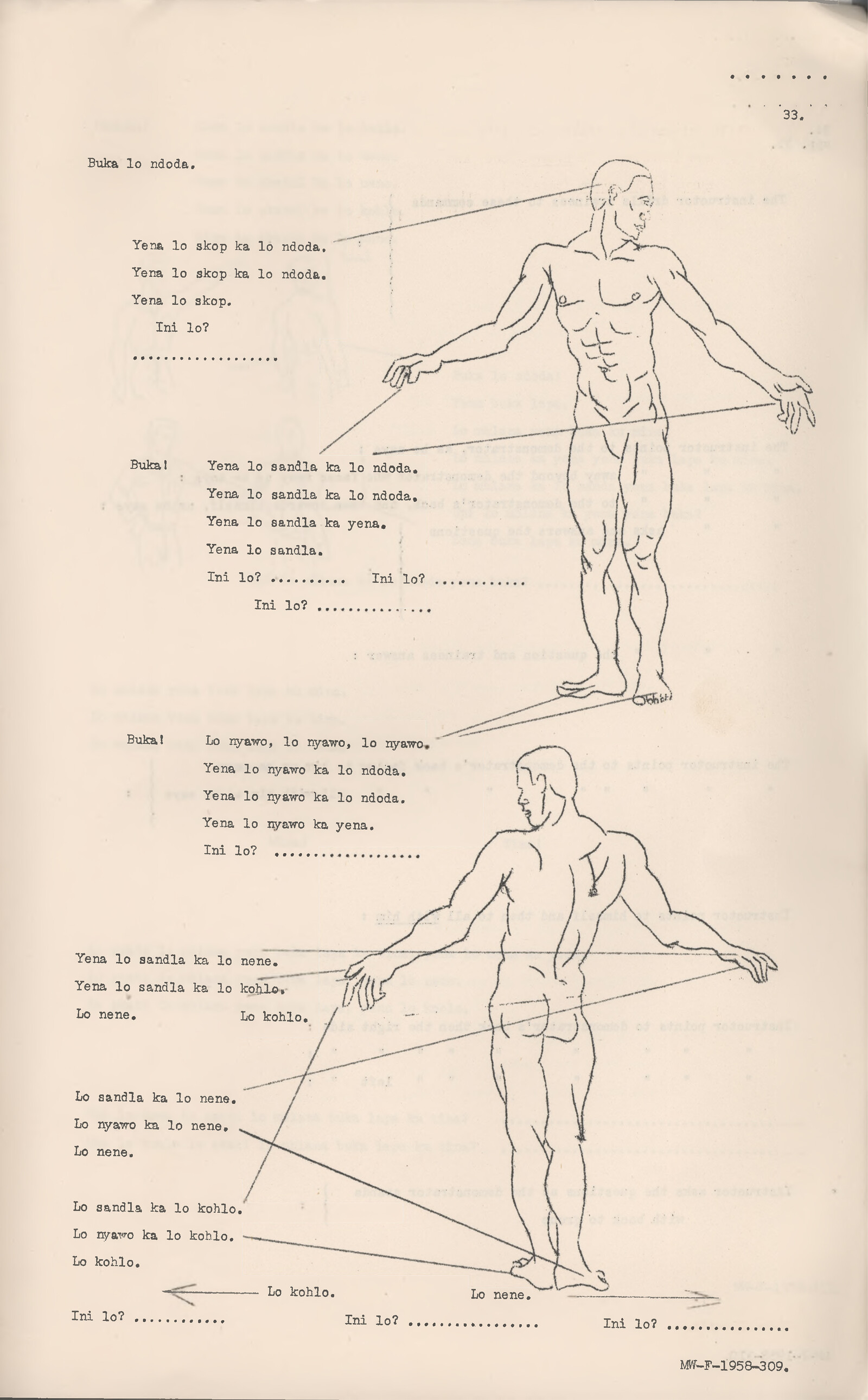

The apartheid apparatus of the South African state is remembered as “technologically advanced.” Early on, the regime pursued technological projects designed to differentiate South Africa from other African countries, in order to demonstrate its modernity through sophisticated technologies of surveillance and warfare and to impose various methods of population control, ranging from passbooks to what would later become a sophisticated biometric system.7 In the 1980s, anti-apartheid movements outside South Africa claimed that attempts were being made to automate apartheid using advanced computer technology, and called for a boycott on the purchase of computers and other technologies.8 The regime’s achievements were in part facilitated by international bank loans and trading activities with the international community.9

In contrast, the story of the Technical Committee is little known. The South African national liberation struggle is not remembered as being tech-savvy, despite the fact that the Technical Committee focused part of its attention on developing various technical devices. This strategy was made necessary by the exiled condition of many leaders, cadres, and rank-and-file members of the liberation struggle.10 Radio Freedom, for instance, was set up in a number of African countries to broadcast revolutionary narratives on short-wave radio, including statements from exiled leaders, news reports, and banned music, both within South Africa and abroad.11 This was enabled by the pan-African solidarity of countries such as Tanzania and Zambia.

Aware of the risk of the apartheid regime jamming the airwaves, the Technical Committee created another broadcast tool to ensure that South Africans could listen in using nearby signals. They designed small boxes that were easy to transport or manufacture locally, including an audio amplifier connected to a tape recorder. A freedom fighter could leave one of these devices in a crowded area and, after a delay, a short message (about five minutes) would play. The Technical Committee also built “leaflet bombs,” a less common form of broadcasting than radio for mass communication, where small detonators would launch leaflets with revolutionary messages into crowded areas.12 And due to the apartheid regime’s routine surveillance of phone calls and postal mail, and tracking of the movements of freedom fighters both inside and outside South Africa, the Technical Committee also relied on plain old hand-written cryptography for conveying private communications from one freedom fighter to the other.

Explosion of a leaflet bomb, seen in film still from Escape from Pretoria, 2020.

The Computer Turn

In the early 1980s, members of the Technical Committee, namely Ronnie Press—a professor of chemistry at Bristol Technical College and member of the outlawed SACP, who worked actively with trade unions—and Tim Jenkin decided to explore digital and transnational communication using newly available and affordable laptop computers and modems in the UK. Jenkin had just joined the Technical Committee after escaping from Pretoria Prison, following his imprisonment under terrorism charges as a leaflet bomber in Cape Town.13 After months of experimenting on laptops with programming and encryption, the Technical Committee found a way to encrypt their computer communications using an automatically-generated, one-time pad.14 They could also exchange messages between London and Bristol using Prestel, a videotext (television and phone) system developed by the British Post Office.15 Despite the commercial failure of Prestel and the UK’s later Telecom Gold system, they were essential to the Technical Committee’s vision of digital communication and the committee’s implementation of an encrypted communication infrastructure.

In 1986, when Tim Jenkin was visiting Lusaka to train freedom fighters to use the devices developed by the Technical Committee, he met with Mac Maharaj. Mac had been released a few years earlier from Robben Island, where he was imprisoned in the mid-1960s; his partner, Zarina Maharaj, was a mathematician who had dedicated her life to the struggle after a career as a system analyst at Xerox in the UK. Mac, who was the commander of a new secret operation named Vula, knew nothing about computers, but Zarina did, so he invited her to the meeting. Mac had previously learned that a group of technical subversives in the UK were testing ways to automate encryption with computers to communicate transnationally.16 Operation Vula was established to use the encrypted communication system as a way to bring key leaders back from exile to steer the machinery of mass movement against the apartheid regime from the ground.17

At the meeting, Zarina was assigned the task of testing a line of communication between Lusaka and London, but was unable to connect through the regular modem used in the UK because the Zambian phone lines would constantly drop.18 To counter this problem, Jenkin looked into coupler modems, which were already being used by journalists to communicate with their reporting agencies in Africa, including Zambia, where phone lines were usually noisy and full of static.19 The acoustic modem offered a particular advantage as it transformed textual data or, more generally, an electric signal, into an audio format that could be sent and received through telephone. Once the solution was proved to work between the UK and Zambia, it needed to be tested in South Africa. As all the members of the Technical Committee were personae non gratae in South Africa, they asked Frans, a Dutch activist to make an inventory of phone booths in three cities—Johannesburg, Pretoria, and Durban.20 Public phone booths were to be used by operatives as a means to send messages to London.

On July 31, 1988, senior ANC cadres filtered back into South Africa from Swaziland to start Operation Vula. A few months earlier, as the communication infrastructure was being fine-tuned and South Africans were getting ready for infiltration, Dutch and Canadian operatives—many of them women—were recruited to set up safe houses in Johannesburg and Durban to host the computer equipment and operate the system from Lusaka. The system was extended first to Tallcree First Nation and then to Edmonton in Alberta, Canada, where an exiled South African had been recruiting Canadians to support the struggle and to co-organize campaigns lobbying the Canadian government not to trade with South Africa.21

With the communication infrastructure fully functional, Janet Love and Susan Tshabalala—comrades operating the system from South Africa—sent information each day about the realities on the ground, in addition to communicating information about logistics and organization.22 The system allowed them to get banned publications, many of which were produced in London—such as the SACP quarterly newsletter Umsebenzi and the ANC newsletters Sechaba and Mayibuye—into South Africa. Now, each new newsletter issue could be received, printed, and distributed within South Africa at almost the same time as it appeared in Britain, with no need for foot couriers to deliver them from Lusaka or the UK.

In early July of 1990, the apartheid government’s Security Branch arrested two operatives in Durban, and found in their possession floppy disks containing a list of operatives’ names, safe house locations, and UK phone numbers, among other details.23 Following this discovery, more South African cadres and operatives were arrested, while others went deeper underground and the Dutch and Canadians fled the country. When the arrested operatives were granted amnesty a few months later and released from prison, exiled South Africans came back to the country. The release of Nelson Mandela after twenty-seven years in prison and the unbanning of the ANC, MK, and SACP at this same time ushered in the beginning of the political transition period in South Africa, which ultimately resulted in the country’s first democratic elections taking place in 1994. In this context, there were no further reasons to keep the secretive Operation Vula active, and so it ceased to exist.

From 1991 to 1992, Operation Eugene replaced Operation Vula. While the operation was largely dormant, it enabled the exchange of a few encrypted e-mails between the UK, where Ronnie Press was still based, and South Africa, where Jenkin had returned after more than thirteen years in exile. However, it was ready to be activated if negotiations failed or the upcoming elections were lost.24 In the meantime, Jenkin started working for the ANC, setting up a computer infrastructure throughout the country in the run-up to the 1994 election. The aim of this new system was to compile data from different regions of South Africa to understand election trends. Once the ANC was elected in April 1994, and once Black South Africans gained formal legal equality, Jenkin put together a team to create and manage the websites of ANC ministries and parliament and to install e-mails for the ANC.

Epilogue

Following the achievement of legal equality for all, the neoliberal post-apartheid era has been mired in gross inequalities, police brutality, state surveillance, gender-based violence, xenophobia, and corruption scandals of state capture that have brought state institutions to the brinks of collapse.25 Many activists, groups, and organizations, including Black women, students, journalists, the poor, and workers, are the unsung heroes of today, working and organizing relentlessly to create the conditions for collective freedom. Their commitment to liberating all people and reconstructing social relations is at the heart of the country’s new struggle for liberation.

Now in his seventies, Tim Jenkin too continues his work at the intersection of technology and social justice. In 2003, he developed the Cape Town Talent Exchange (CTTE), the first exchange group in what is now a larger Community Exchange System (CES). CES provides an online platform where goods and services are traded without using a national currency. It is based on the principle that non-monetary exchange helps build community by connecting people and providing a local support network. All transactions are recorded in an online database that Jenkin developed. As of now, the CES has grown to 1,147 exchange points in 102 countries. In an interview, Jenkin explained that, when developing the encrypted communication system, he believed that an economic system could be replaced by overthrowing a government.26 But he quickly came to understand that, even with the election of the ANC in 1994, they would not and could not change the economic system that prevailed globally. What was needed was an alternative economic system that did not rely on money and that could co-exist with the dominant system. Creating an autonomous, self-generated system that provides freedom from money with and through community is Jenkin’s new way to continue his activism. The struggle continues.

The message excerpts have been edited for ease of reading.

This short introduction focuses only on an early version of the encrypted system, which was frequently updated over the years. Further, it is very much influenced by the article: Sophie Toupin, “Gesturing towards ‘anti-colonial hacking’ and its infrastructure,” Journal of Peer Production 9, September 2016, ➝.

“Operation Mayibuye,” Historical Papers Research Archive, William Cullen Library, University of the Witwatersrand, ➝.

Garth Benneyworth, “Rolling up Rivonia: 1962–1963,” South African Historical Journal 69, no. 3 (2017): 404–417.

Stephen Ellis, External Mission: The ANC in Exile, 1960–1990 (London: Hurst, 2012).

Sophie Toupin, “Technically Subversive: Encrypted Communication in the South African National Liberation Struggle” (PhD diss., McGill University, 2020).

Keith Breckenridge, Biometric State: The Global Politics of Identification and Surveillance in South Africa, 1850 to the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014). See also Paul N. Edwards and Gabrielle Hecht, “History and the technopolitics of identity: The case of apartheid South Africa,” Journal of Southern African Studies 36, no. 3 (2010): 619–639.

NARMIC/American Friends Service Committee, Automating Apartheid: U.S. Computer Exports to South Africa and the Arms Embargo (NARMIC/American Friends Service Committee, 1982). See also Komitee Zuidelijk Afrika, Computerizing Apartheid: Export of Computer Hardware to South Africa, trans. Mohamed Munaf, Kirsten Olofsen, and Gert Slob (Holland Committee on Southern Africa, 1990).

South African Democracy Education Trust, The road to democracy in South Africa, vol. 3, International Solidarity Part 1 (Pretoria: Unisa Press, 2008). See also Part 2 of the same book.

AbdouMalik Simone, “People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg,” Public Culture 16, no. 3 (2004): 407–429.

See Sekibakiba Peter Lekgoathi, “The African National Congress’s Radio Freedom and its audiences in apartheid South Africa, 1963–1991,” Journal of African Media Studies 2, no. 2 (2010): 139–153; Guerrilla Radios in Southern Africa: Broadcasters, Technology, Propaganda Wars, and the Armed Struggle, eds. Sekibakiba Peter Lekgoathi, Tshepo Moloi, and Alda Romão Saúte Saíde (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2020).

The purpose of these airborne leaflets was to wake South Africans up to the anti-apartheid cause. See Tim Jenkin, Escape from Pretoria (London: Kliptown Books, 1987).

See Sophie Toupin, “Escape from Pretoria,” hack_curio, August 14, 2019, ➝.

A one-time pad is a form of symmetric cryptography that pairs a plaintext with a pre-shared secret key.

Prestel was seen as a way to deliver information services into British homes and display the content on television sets. As a declining power in geopolitics and global manufacture, Britain had decided to pivot to a new information economy in the 1960s, investing massively in videotext technology as a competitor to the American ARPANET system, the ancestor of the Internet. See John Carey and Martin Elton, “The Other Path to the Web: The Forgotten Role of Videotex and Other Early Online Services,” New Media & Society 11, nos. 1-2 (2009): 241–260.

Mac Maharaj in conversation with the author, November 2018.

See R. Kelly Garrett and Paul Edwards, “Revolutionary secrets: Technology’s role in the South African anti-apartheid movement,” Social Science Computer Review 25, no.1 (2007): 13–26. See also Padraig O’Malley. Shades of Difference: Mac Maharaj and the Struggle for South Africa (NY: Penguin Books, 2007).

Zarina Maharaj in conversation with the author, January 2019.

Tim Jenkin in conversation with the author, September 2018.

Conny Braam in conversation with the author, February 2019, and Frans in conversation with the author, February 2019.

Joe in conversation with the author, November 2018.

Janet Love in conversation with the author, October 2018, and Susan Tshabalala in conversation with the author, November 2018.

The two operatives, Mbuso Shabalala and Charles “Francis” Ndaba, were both killed by the apartheid regime.

Tim Jenkin in conversation with the author, September 2018.

Andy Clarno, Neoliberal Apartheid: Palestine/Israel and South Africa After 1994 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

Jem Bendell, “The Harry Potter of Jailbreaking: Tim Jenkin on Freedom,” YouTube, May 8, 2017, ➝.

Coloniality of Infrastructure is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, Critical Urbanisms at the University of Basel, and the African Centre for Cities of the University of Cape Town.