1989 was the year the Berlin Wall fell. The year of protests in Tiananmen Square. The year Frederik Willem de Klerk initiated the end of apartheid in South Africa. It was also the year that a radical techno-social invention started to reshape the way the planet operates, an invention intended to redefine the way finance, environments, cultures, and bodies relate to each other, yet one that was embedded so effectively in the contemporary architecture of power that it could hardly be perceived.

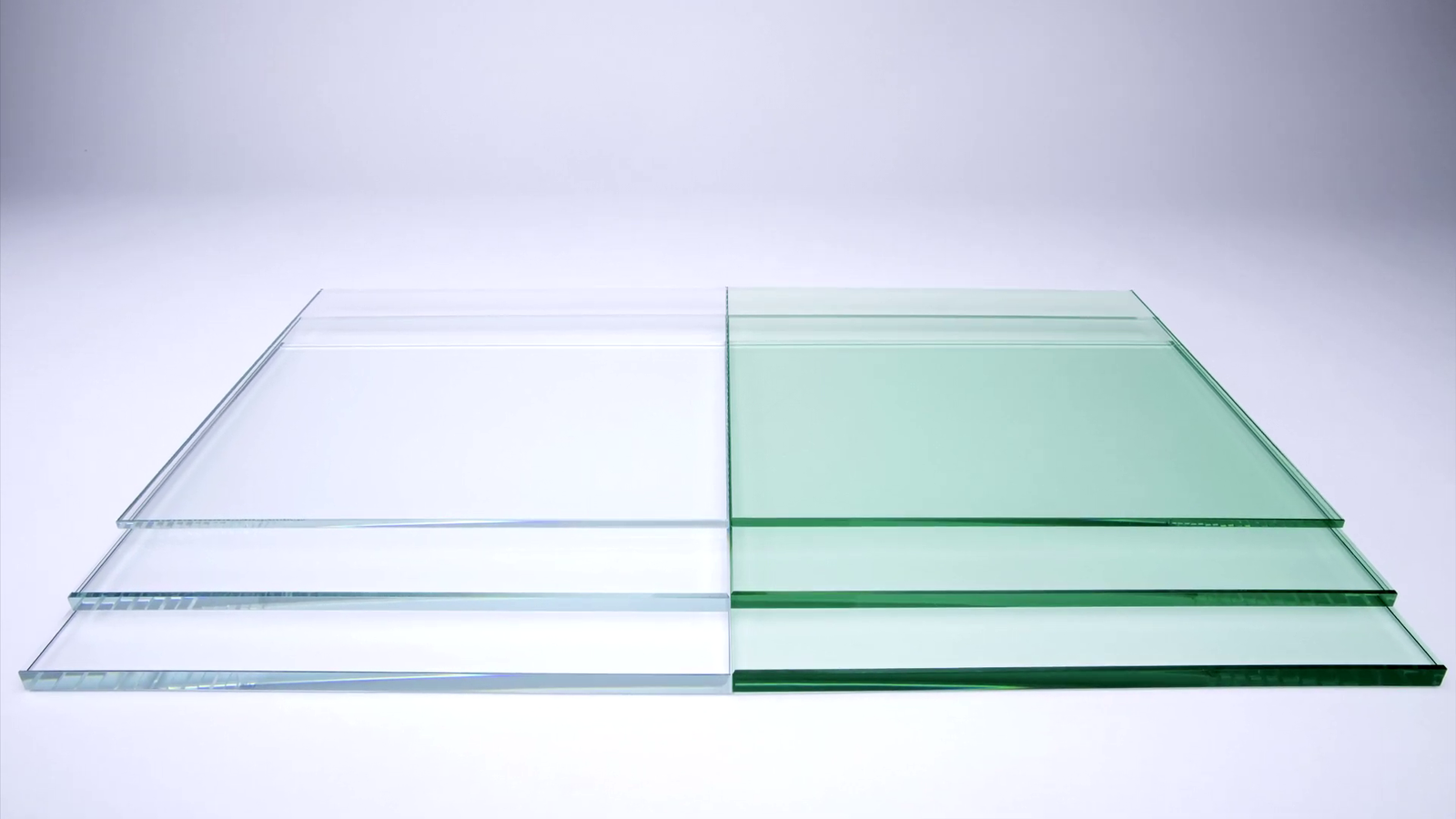

In 1989, PPG Industries patented Starphire, the first industrially produced low-iron floated glass.1 This surprisingly clear glass rapidly became a most desired architectural component and an indicator of global financial power. By 2008, four transnational corporate giants—Saint Gobain, Guardian Glass, Pilkington, and AGC—had stabilized a steady 6% annual growth in the production of Ultra-Clear Glass (UCG).2 With an annual production of 2,271,000 tons, the UCG industry is projected to reach a yearly revenue of $5.1 billion by 2021.3 It is commercialized under brands such as Starphire, Diamant, Clearvision, Optiwhite, and AGC Clear.

Fifty-nine years after Buckminster Fuller and Shoji Sadao imagined a three-kilometer glass dome covering Manhattan’s midtown corporate power, countless pieces of UCG, distributed worldwide, have encapsulated the daily life of the global wealth of the planet, enclosed in a consistently blue-skied environment of apartments, offices, engineered landscapes, and transportation devices. Sold as the top premium product of the glass industry, the price of UCG is at least 30% higher than any standard clear glass.4 Exceptional clarity. Optimum transparency. Unfiltered natural light. Unrestricted views. Colorless appearance. Purity of color. It has become so pervasive that it is invisible to those who inhabit it. Literally invisible. Ultra-clear invisible.

Since 2008, the consumption of UCG in the world has doubled.5 UCG has become a pervasive material in office, apartment, and commercial buildings in wealthy, global, urban settings. According to Vitro Architectural Glass’s online project browser, UCG can be found in the headquarters of Apple, Amazon, Alcoa, Google, Goodyear, Comcast, Ernst and Young, and Sinopec; in the $238 million penthouse at 220 Central Park South; in the $91 million condominium of 432 Park Avenue, the Seoul Hyatt Hotel, Cornell Tech’s educational hub, Terminal 5 of Chicago Airport, and the Langone Medical Center in New York; in Bentley, Audi, and Mercedes Benz cars.

UCG is composed of 73% SiO₂, 14% NaO₂, 10% MgO, and 1% Al₂O₃.6 With an iron content below 0.01% (ten times less than ordinary glass), UCG reaches up to 97% of light transmittance and allows for a high degree of control over what passes through it and what doesn’t.7 UCG is the best performing clear panel used to engineer the transmittance of incoming and outgoing radiation in buildings with glass envelopes.8

In UCG, light transmittance is higher in the cold fraction of the light spectrum—the blue zone that runs between the 450–550 nanometer wavelength.9 As a result, Ultra-Clear Glass makes everything look more blue. It makes the sky more blue than it really is to those who can afford to look out through it. Yet the yellows, oranges, and reds that are filtered out of the sky do not disappear; they are offsetted.

UCG requires silica sand with an almost non-existing content of iron oxide as a raw material. Companies providing high-quality, low-iron silica sand worldwide, such as Fairmount Santrol or US Silica, concentrate their production in Illinois and Wisconsin. The product is known as St. Peter Sandstone. Its use by both UCG and the fracking industries has led to a growth in surface mining in these areas,10 as well as the pollution of farmland and water bodies, an increase in atmospheric concentrations of CO₂ and NOx, and the exponential growth of lung-affecting diseases such as silicosis and carcinoma.11

The presence of iron oxide in silica sand, the raw material of all glass, both lowers its melting point and helps shorten its cooling time. The production of UCG thus increases the energy required to melt the sand by thirty percent and doubles the energy required to slow down the process of cooling. 73% of the energy fueling the production of UCG comes from natural gas, which at least in the United States, comes from fracking.12 Even though the production of a ton of Starphire glass generates 40% more CO₂, 400% more SO₂, and 400% more O₃ emissions than a ton of Portland cement, when applying for a LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) rating, two points are automatically earned when UCG, with its LEED-certified Environmental Product Declaration, is installed.13

UCG is not just a construction solution, but a socio-territorial apparatus. It segregates a blue-skied society from those who bear the environmental cost in locations not visible from their UCG-glazed interiors, no matter how tall the building is. Blue, offsetted skies have even become, perhaps unwittingly, emblematic of social inequality. According to Ryan Cohn, art director of Neoscape Inc., a full-service creative agency specialized in branding and visual storytelling for high-end and luxury real-estate ventures, “Clients always want it blue.”14 They want the glass in the renderings of their buildings to be UCG regardless of what kind of glass they will end up using.15 They want to see a blue version of the city sky, both through and reflected in UCG.16

In the words of Phillip Crupi, a CGI expert, this form of digitally manufactured clarity is meant to “produce the feeling of a simultaneous visual ownership of both the interior and the exterior.”17 As important as it is for prospective clients to gain access to helicopter views, so is the possibility for interiors to be constructed in chromatic and light continuity with those views they have privileged domain over. Clarity is how power stabilizes value. The capacity to represent clarity makes CGI an actor in the making of social difference.

Yet according to CGI expert Joseph A. Brennan, glass is the “only remaining artistic frontier.”18 The depiction of UCG with levels of light transmittance that make it almost invisible still challenges the capacities of the best CGI artists.19 Sometimes it is even depicted as a literal lack of cladding, with mullions floating in the air.

Vitro Architectural Glass, Sustainable in Every Light, December 2017, ➝.

“Global Ultra Clear Glass Market 2019 to 2023,” ReportsWeb, June 2019, ➝.

Ibid.

“Glass Price Calculator,” Crystal Glass and Mirror Corporation, accessed September 21, 2019, ➝.

“Global Ultra Clear Glass Market 2019 to 2023,” ➝.

Vitro Architectural Glass, Starphire Technical Product Data, October 2017, ➝.

Guardian Glass Industries, Guardian Clarity: Anti-reflective Glass in Architectural Applications, 2016, ➝.

“The Original Environmental Performer,” Vitro Architectural Glass, accessed September 21, 2019, ➝.

Vitro Architectural Glass, “Sustainable in Every Light,” ➝.

Steven Ralston, “Select Sands Begins Shipping Industrial Sand; Resource Estimate Increases 91%,” Seeking Alpha, May 10, 2016, ➝.

Sally Younger, “Sand Rush: Fracking Boom Spurs Rush on Wisconsin Silica,” National Geographic, July 4, 2013, ➝.

“Glass Manufacturing is an Energy-Intensive Industry Mainly Fueled by Natural Gas,” Today in Energy, U.S. Energy Information Administration, August 21, 2013, ➝.

Vitro Architectural Glass, EPD Vitro Architectural Glass Flat Glass Products, July 2017, ➝.

Ryan Cohn, interview with author, June 21, 2019.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

John Szot, interview with author, June 17, 2019.

Ultra-Clear Glass is only visible in CGI through three features: residual blueish tones, rainbowy edges and reflections, and slight reflections and fake imperfections on the invisible glass surface. J. Cseh and S. Chappell, interview with author, June 19, 2019.

Collectivity is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the 2019 Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism within the context of the “Collective City” thematic exhibition, and was made possible thanks to the support of the Creative Industries Fund NL.

Category

Research Team: Andrés Jaque, Marcos García Mouronte, Jesse McCormick, Eno Chen.

Collectivity is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the 2019 Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism within the context of the “Collective City” thematic exhibition.