Feminist spatial practices are multidimensional and multifaceted expressions of thinking and acting, with an aim to build spatial justice and enable better caring in a world defined by ideologies of injustice and regimes of inequity.

—Elke Krasny1

Feminisms are myriad and countless. In every region, specific movements and discourses about gender emerge, entangled with local political struggles and cultural histories. Ideas shift and move between geographies, gaining new allegiances, oppositions, and transformations. Individuals invent their own everyday methods of pushing on gender norms, with or without any affinity to the word “feminist.” These countless feminisms produce both methods of resistance—for critiquing and countering oppressive power structures—as well as alternative projections—for imagining and enacting more equitable, supportive, and sustainable worlds. A vast landscape of feminist spatial practices around the world, stretching back in time and forwards into the future, resists power and imagines new futures through experimental storytelling, community-building, educating, material testing, and fabricating new architectures.

Feminist spatial practices often defy disciplinary boundaries, slipping between art, architecture, theory, and social practice to enable more equitable social and spatial environments for intersectionally marginalized communities. Despite this kaleidoscopic range, the fields of the built environment continue to treat feminism as a numbers game: a quantitative problem of packing more, typically cis-gendered, women into practices, faculties, dean’s offices, and board rooms. Representation does matter, but representation without other changes leaves existing patriarchal, capitalist, and colonialist systems intact. In contrast, this project points to the range of intersectional, multiscalar, and relational practices that expand ways of thinking and making in the built environment.

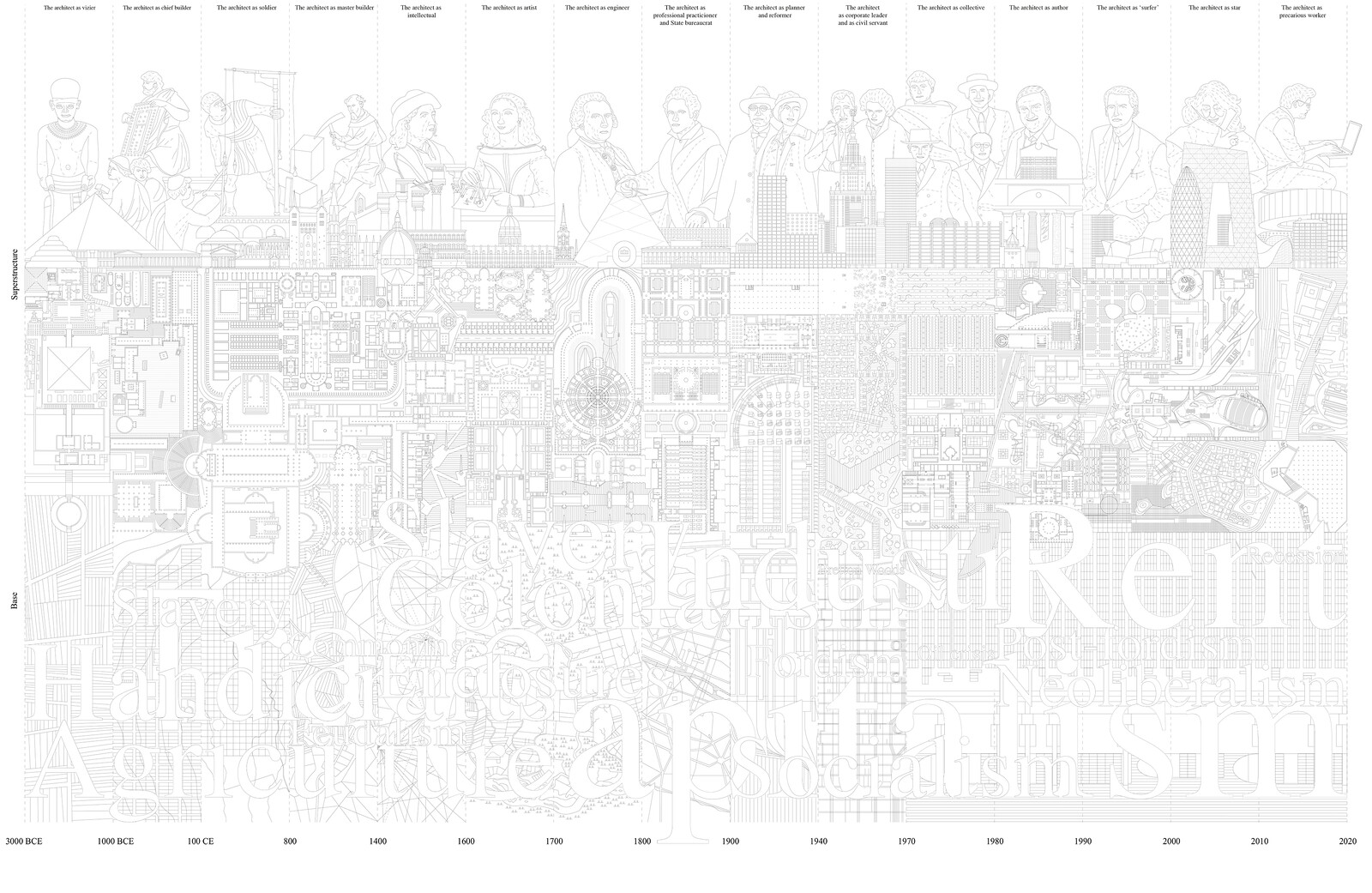

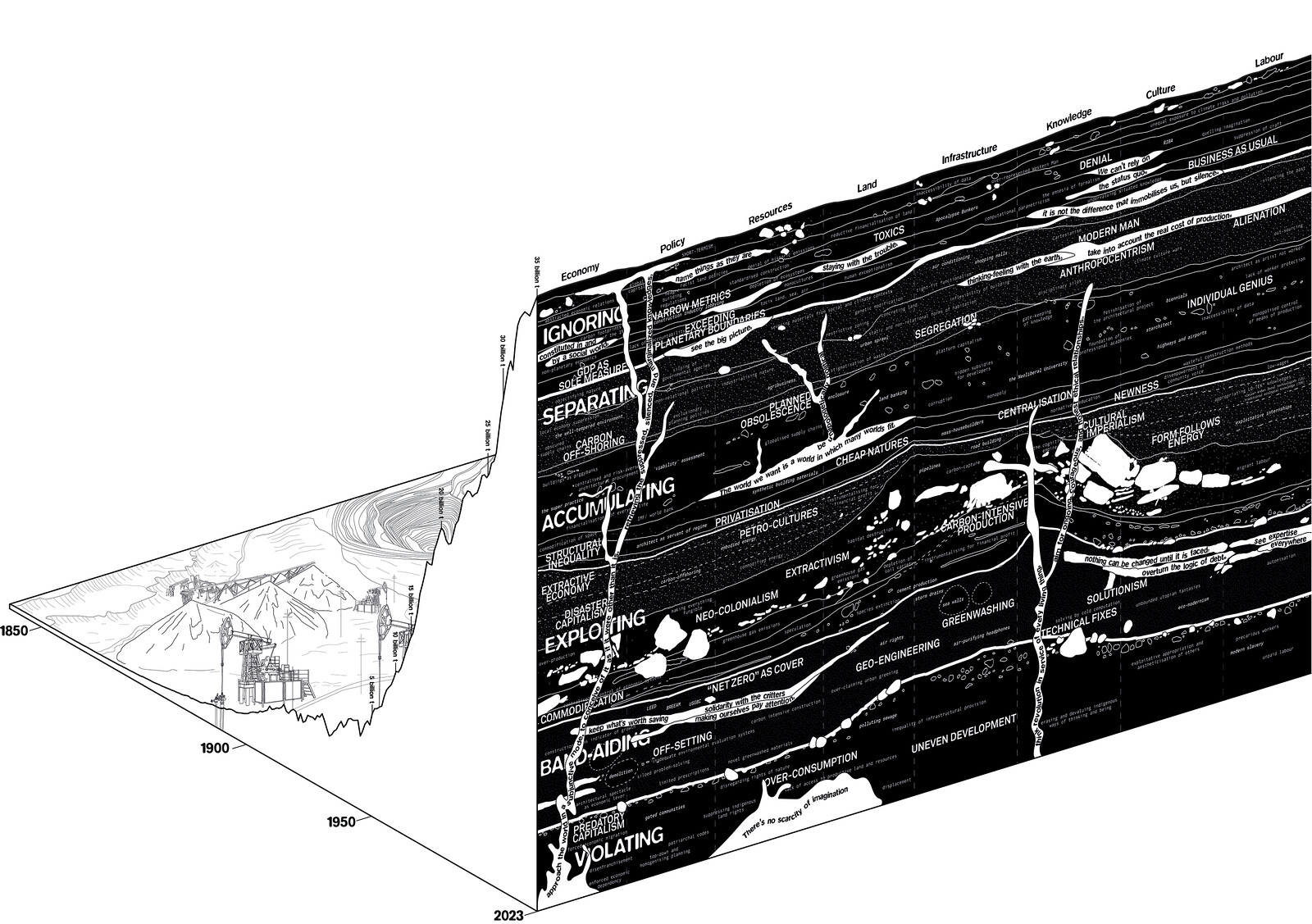

While it is impossible to depict the full range of global practices in one drawing, this diagram offers one vantage point onto the undulating terrain of interconnected feminist practices. It points to six ways in which contemporary feminist spatial practices are remaking the fields of the built environment: experimental pedagogies, expanded histories, embodied theories, collaborative practices, spaces for non-conforming bodies, and alternative materialities. These modes of practice emerge in relation to activist movements and political conflicts around the world, depicted here as a diagonal axis of ongoing political struggles. The diagram is the first part of a larger, participatory project to celebrate the range of contemporary feminist spatial practices, the goal of which is not to create a new canon, but to facilitate making kin. Visibility enables solidarity. The process of realizing the project aims to be a feminist practice itself, one of building community and celebrating global, situated perspectives.

The first part of the project—this diagram—works with the possibilities and limitations of a visual timeline to express relationships between contemporary feminist spatial practices, political movements, and theoretical discourses. It is meant to be a conversation-starter, an invitation to an ongoing global discussion. The second part will be an open-source, online platform that brings together feminist spatial practices from around the world to enable both visibility and community building, the format of which will be determined by its participants. If you would like to submit comments, ideas, or suggestions about any aspect of the project and/or to express interest in participating in the second phase, please follow this link.

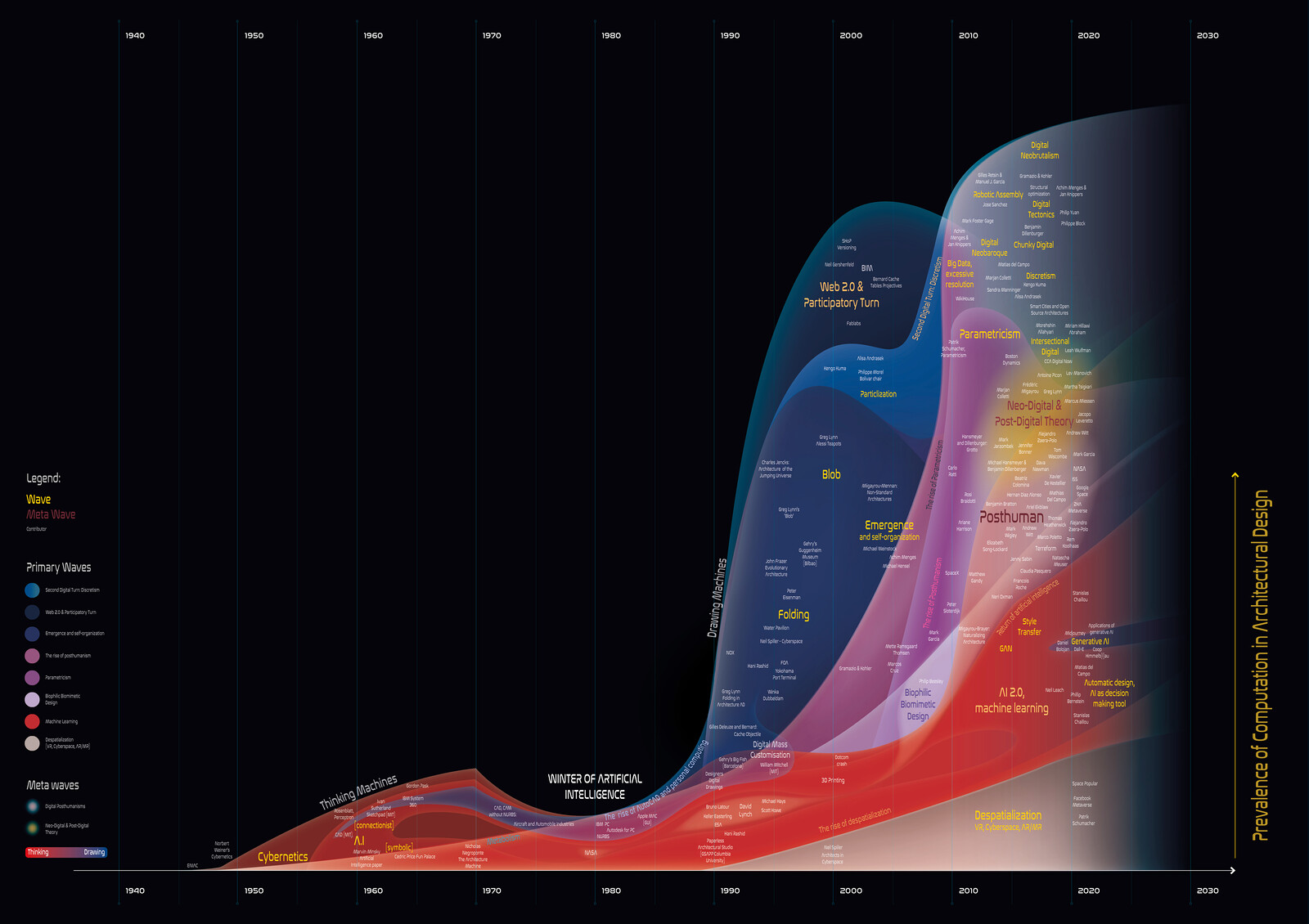

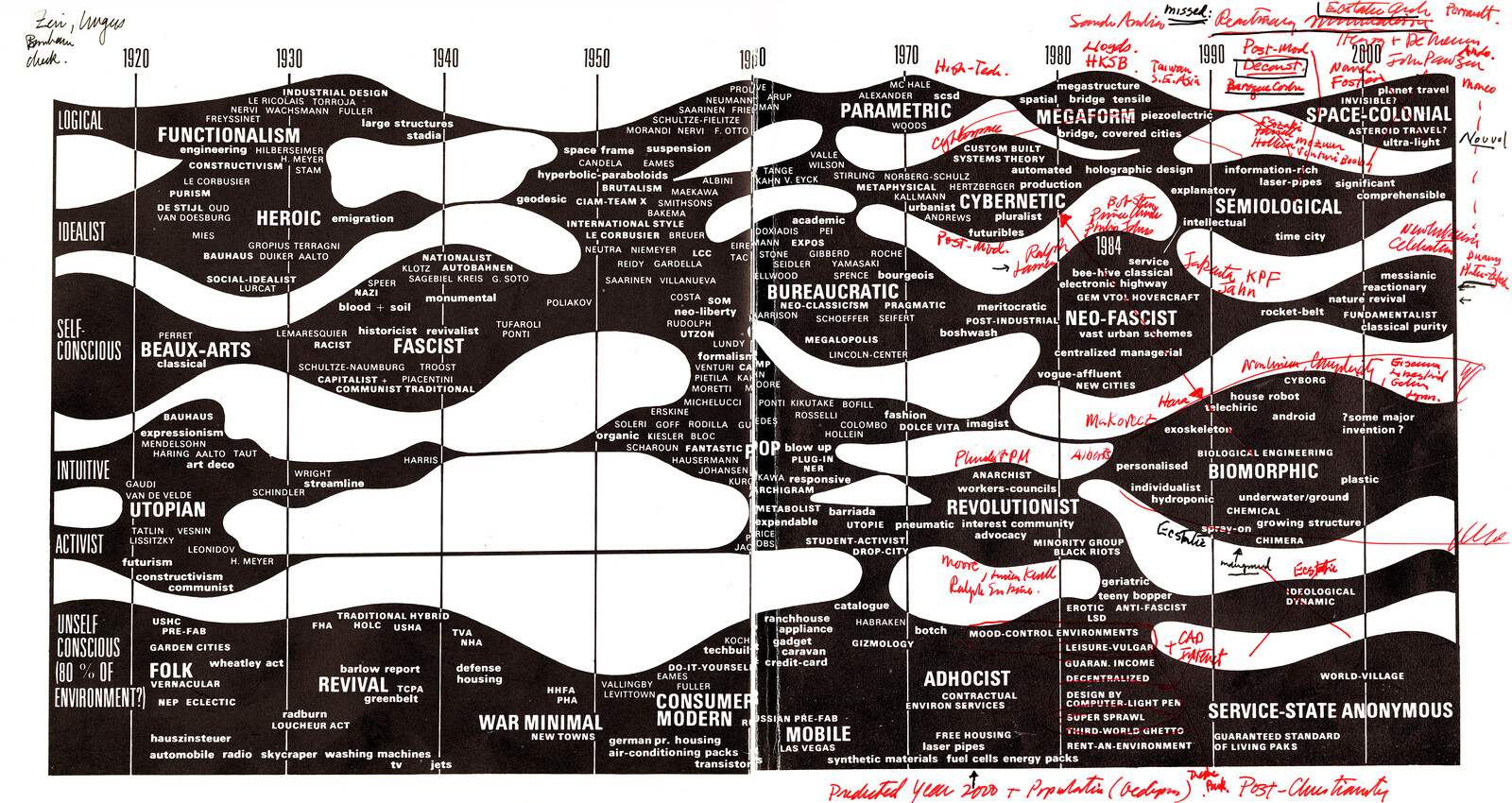

Part 1 wrestles with the dissonance between the format of a timeline and feminist epistemologies. Charles Jencks’s evolutionary diagrams, and the long lineage of historical cartographies of time he worked with, use visual expressions to map historical changes.2 The visual, relational format of these diagrams partially destabilizes the linearity of a written history and introduces slippages between form and content. Nonetheless, they reinforce a singular, all-knowing view of the world. Such omniscience is precisely what feminist theorists and historians have challenged, as beautifully manifested by the recent Feminist Architectural Histories of Migration project.3 The discourses of intersectional and decolonial feminisms emphasize that knowledge is partial and situated, emerging from lived experiences of individuals as well as the social, political, and economic contexts in which they dwell.4 Dialogue between many voices can identify overlapping experiences, but also dissonances, in an embrace of knowledge as relational and incomplete.

It is in this spirit that Part 1 grew from dialogue with many voices and, through its incompleteness, points to future iterations and participatory formats. We, Bryony Roberts and Abriannah Aiken, are both white cis women based in the United States with knowledge primarily of anglophone feminisms. The process of creating Part 1 aimed to learn from as many perspectives as possible within a limited time frame to expand beyond this positionality. It builds on many existing collective projects to gather and celebrate feminist practices and design activism.5 In addition, we held informative conversations with feminist scholars and practitioners: Kadambari Baxi, Lori Brown, S. E. Eisterer, Ruo Jia, Elke Krasny, Korantemaa Larbi, Ana María León, Ishita Shah, Anooradha Siddiqi, Tijana Vujosevic, Alla Vronskaya, Sumayya Vally, and Mimi Zeiger. Virginia Black, Lindsay Harkema, and Jerome Haferd offered further suggestions for the visualization. Each interlocutor offered conceptual and/or concrete suggestions for structuring the project.

The diagram was created through an interpretive process of visualization based on these conversations and feedback. The resulting visualization is a landscape of ideas and practices: a relational terrain of parallel, interrelated, and sometimes conflicting modes of feminist spatial practice. Inspired by geological maps, the diagram shows landforms of converging ideologies and activism that rise from seas of oppressions. The land masses morph over time, expressing the shifting relationships between activist movements, theoretical discourses, and modes of spatial practice, focusing primarily on contemporary practices, yet with nods to earlier influential projects and practitioners. Time travels along a diagonal axis of political struggles beginning in the late 1960s and moving to the present, indicating that political crises are often precipitating factors for feminist movements and discourses. The landscape also runs off the page in all directions, inferring that feminist spatial practices happened before the frame of this landscape and will continue to happen afterwards. Peaks of theory and practice emerge, but exist in all time periods and landscapes, showing ever-expanding relational conditions rather than hierarchy.

The seven geological masses emerge from a troubled body of water. The water exists within and around the mountains, flooding and eroding feminist spatial practices: white supremacy, homophobia, right-wing extremism, etc. The water and mountains are entangled in a landscape of tension and conflict; a swampy archipelago of both insidious erosion and persistent resistance on behalf of feminist artists, architects, and practitioners through time. At the top of the cartographic map is a hopeful imaginary of the future: an even more connected and impervious landscape of collaboration, resistance, and intersectional inclusion. In the supplementary diagram, an even more saturated reality emerges, with photographic examples of feminist spatial practices enriching the landscape. The two diagrams embrace instability and fluctuation as colors and textures flicker through time, pointing towards ever-changing, ever-shifting, and ever-growing feminist futurescapes.

The diagram is inevitably incomplete as the intertwined relationships between political, theoretical, and creative movements are complex and wildly different across geographies. Instead of a comprehensive historical survey, the diagram instead points to thematic groupings that describe how feminist spatial practices introduce expanded conceptual frameworks for pedagogy, historiography, theory, practice, programming, and materiality. Wherever possible, we aimed to show the range of work being done on each theme across different geographies and mediums as best we could from our vantage point. Across these disparate modes of practice, feminist thinkers and makers are showing how the fields of the built environment can move away from exploitative, oppressive systems towards more expanded worlds of intersectional solidarity. We hope that you will join us in creating Part 2, an evolving and dynamic platform for identifying, celebrating, and discussing feminist spatial practices.

Elke Krasny, “Scales of Concern: Feminist Spatial Practices,” Empowerment, Edited by Andreas Beitin, Katharina Koch, and Uta Ruhkamp (Wolfsburg: Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 2022), 185.

Daniel Rosenberg and Anthony Grafton, Cartographies of Time (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2010).

Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi and Rachel Lee, “On Collaborations: Feminist Architectural Histories of Migration,” Aggregate (2022); Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi and Rachel Lee, “On Margins: Feminist Architectural Histories of Migration,” Architecture Beyond Europe 16 (2019); Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi and Rachel Lee, “On Diffractions: Feminist Architectural Histories of Migration,” Canadian Centre for Architecture (2021–22).

Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color,” Stanford Law Review, Vol. 43, No. 6 (1991), 1241-1265, 1296-1299; Avtar Brah and Ann Phoenix, “Ain’t I A woman? Revisiting Intersectionality,” Journal of International Women’s Studies Vol. 5, No. 3 (2004), 75-86; Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575–99, ➝.

A.L. Hu, Elizabeth Keslacy, S.E. Eisterer, Dubravka Sekulic, Rebekka Kiesewetter, Pat Morton, Armaghan Ziaee, the FemArk Project, Mechtild Widrich, Ayala Levin, and Ana María León, eds., Space/Gender Reading List, on-going, ➝; Torsten Lange, Charlotte Malterre-Barthes, Daniela Ortiz dos Santos, and Gabrielle Schaad, eds., “Zeitgenössische Feministische Raumpraxis,” ARCH+, no. 246 (February 2022), ➝; Gilly Karjevsky and Rosario Talevi, “The Outdoors,” e-flux (October 2021), ➝; Meike Schalk, Thérèse Kristiansson, and Ramia Mazé. eds., Feminist Futures of Spatial Practices (Baunach: AADR, 2017); Lori Brown, Feminist Practices: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Women in Architecture (London: Routledge, 2011); Architexx, Now What?! Advocacy, Activism & Alliances in American Architecture since 1968, ➝; WAI Architecture Think Tank, A Manual of Anti-Racist Architecture Education, ➝; Beverly Guy-Sheftall, ”African Feminist Discourse: A Review Essay,” Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, 2003, No. 58, “African Feminisms Three” (2003), 31-36; Tatjana Schneider and Jeremy Till, Spatial Agency, ➝; Alla Vronskaya, et al, Women Building Socialism, ➝; Korantemaa Larbi and Ameena Walker, Design233, ➝; Mindy Seu, ed., Cyber-Feminism Index (Los Angeles: Inventory Press, 2022).

Chronograms of Architecture is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Jencks Foundation within the context of their research program “‘isms and ‘wasms.”

Thank you to Kadambari Baxi, Virginia Black, Lori Brown, S. E. Eisterer, Ruo Jia, Jerome Haferd, Lindsay Harkema, Elke Krasny, Korantemaa Larbi, Ana María León, Ishita Shah, Anooradha Siddiqi, Tijana Vujosevic, Alla Vronskaya, Sumayya Vally, and Mimi Zeiger for contributing suggestions and feedback to this project.