Life Support

What time is it? 6am? 10pm? I am once again waking up to the reflection of my face against the perpetual darkness outside, peppered by countless stars and planets in every direction. Timekeeping has been both difficult and somewhat pointless since I left earth. The only thing on this spaceship that really still operates on a “24-hour” cycle is my human body. I eat regularly, I use the restroom regularly, I work regularly, I exercise regularly, and I sleep regularly. I just have no idea what time it is anymore, unless I check my immaculate clock. I simply pass time regularly.

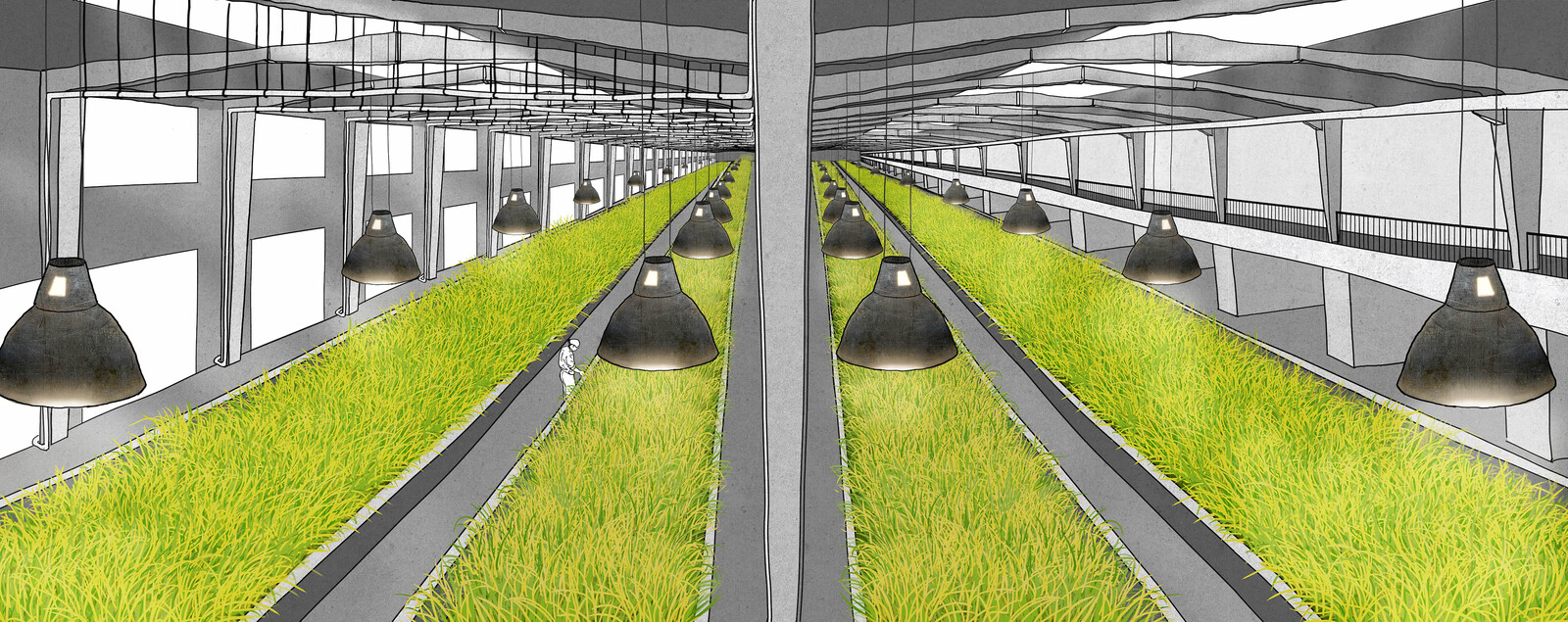

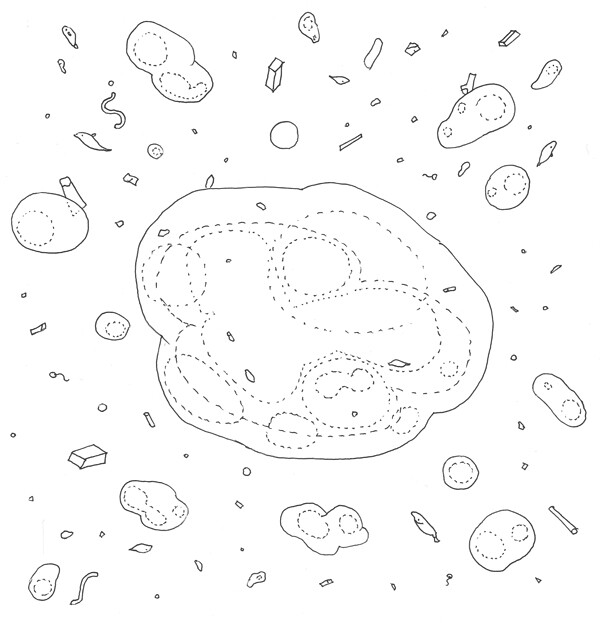

Life on this emergency survival pod has been… lucky. I am one of the very few who managed to escape the world-ending event that happened some time ago. How long ago? Sorry, I can’t remember. Months? Years? Could be years. Definitely months. I can check. I mostly make out the passing of larger units of time by watching the plants and fish grow in my in-unit micro-farm. My spaceship’s life-support agriculture and aquaculture system uses an efficient ultraviolet and hydroponic self-feeding and insta-harvesting automation technology carefully designed for a 2000-calories daily intake cycle. I have been able to eat a very nutritionally balanced, albeit bland, healthy diet.

Whenever I complete a bowel movement, the biomatter gets directly suctioned back into the compost that grows the food. Once a month I get to eat one tilapia. I have to keep at least thirty-six alive in the tank at all times. Sometimes I am a little sad to eat the only other earthlings that keep me company. Alongside my diet, it is vital to maintain a consistent fitness regiment, since my body easily weakens in an environment without gravity. Back on earth, if you told me I’d be eating some kind of a spinach-beet-parsnip-legume concoction as my primary meal for the rest of my life and doing resistance-band daily workouts, I might have said “kill me now.” But, here we are, and I am happy to be alive. The self-sustaining life-cycle on this living module means that I can remain alive “indefinitely.”

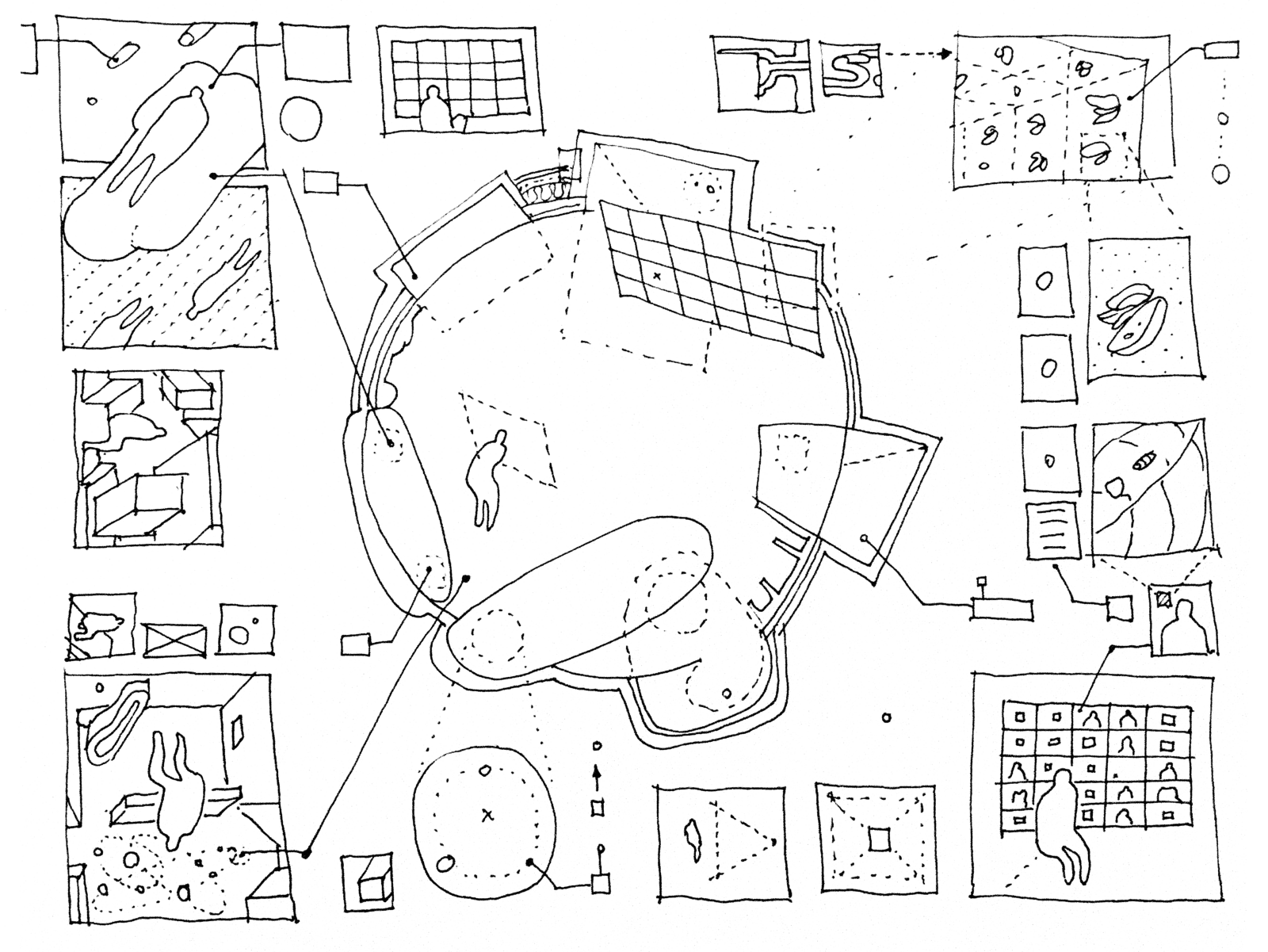

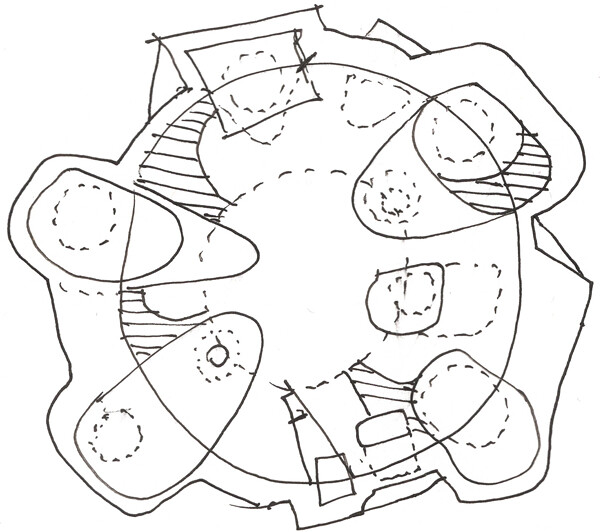

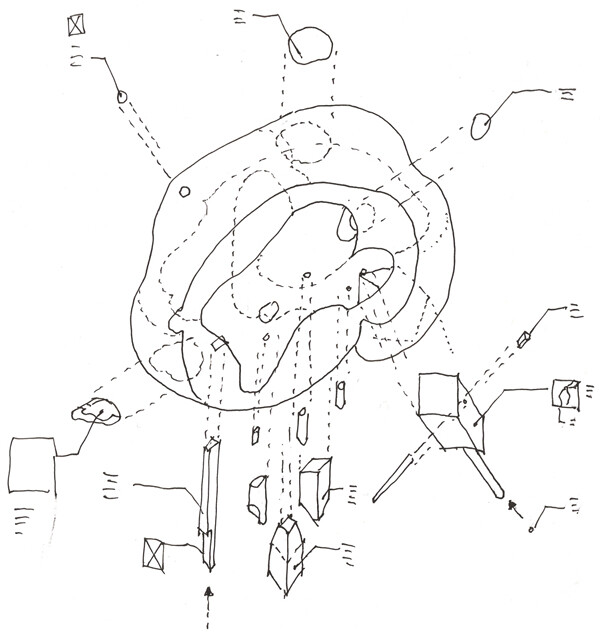

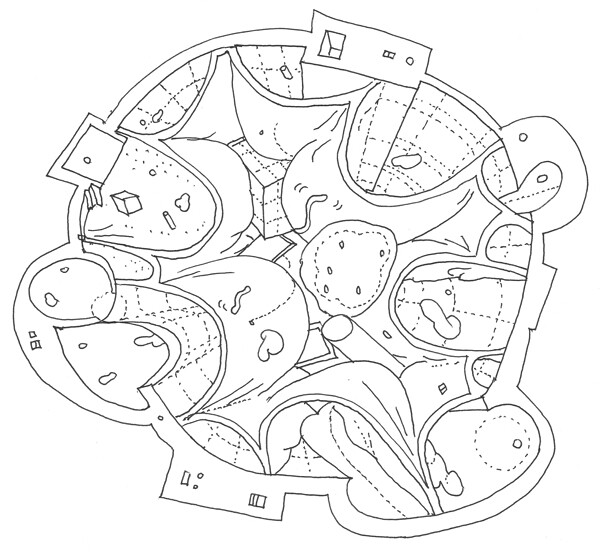

Home is a cylindrical capsule with an interior diameter of seven-and-a-half meters and roughly fifteen meters in length. Life without gravity means I am able to use every interior surface as I float from one zone to another. Architecturally, there are no such things as plans, reflected ceiling plans, elevations; it’s all one continuous surface. Most of the key functional elements are embedded around the parameter of this cylinder—bathroom, storage, communication station, sleeping area, etc. The heating-unit runs on a mini nuclear reactor with a heated recirculation fluid-pumping system that prevents liquid water from entering solid state. I keep the forced-air even at 22°C.

Jimenez Lai, Spaceship Hour, 2021.

The instruction manual recommends that I zip myself into the sleeping zipper and strap my head still so that I don’t wake up with a whiplash. On more reckless days, however, I just let myself go; I simply float about freely while I sleep. The interior is basically an oversized stuffed pillow with a layer of batting dotted by the tufts that pinch the fabric taut onto the structure of the fuselage. Soft surface textures and rounded corners are important when there is no gravity; you never know when you might bump into something that can injure you. It also dampens sound and improves your singing, when one may decide to sing to one’s self. Some surfaces are furry, some are smooth, and others are waterproof. Unrolled, the surface area of the cylindrical interior is 440 square meters. Back where I’m from, I could never afford a property this size.

It’s funny to continue to receive a salary while not being able to spend it. That is, unless you get creative with the idea of expenditure. I suppose my work now is like some kind of a space-janitor who maintains this spaceship while keeping myself alive. I am a space-cyborg custodian. My human body can no longer exist without this oversized exo-suit that wanders aimlessly in deep space, nor would this husk of a spaceship function if I were to die. This interface that I call home is now inseparably fused with me as an extension of my human body. Sustenance work aside, I still dedicate a hobby area to do some work that I still find enjoyable. To pass time. Every so often, I make drawings of people I remember back on earth.

Every now and then, we survivors organize teleconferencing parties so that we can touch-base and check in with one another. Whenever I see that grid of faces I have never met in real life, I wonder if I am happy simply to interact with another human because it is my instinct, or if I feel obliged to be happy because I want the other to be happy too. Some of us have formed task-force assemblies to troubleshoot caloric inefficiencies of our farms, or inventive clean-up concepts to keep our spaceships tidy. There are also support groups for people who mourn the depletion of their fish stock from overeating. One survivor came up with a clever strategy to help these people: for a small fee, you get a micro-dose of electricity through your wristband if you go near your aquarium when the fish-count is low. I personally don’t mind paying the fee, even for the premium account that provides a slightly higher wattage. Most of us really have no other way of spending our money. Plus, it’s nice to keep your fish alive so you can stare at them, or get mildly electrocuted. Both are good ways to pass time.

Jimenez Lai, Spaceship Hour, 2021.

You Up?

03:38am: “You up?”

I was awakened by a notification alert buzz on my wristband. Getting direct messages is rare, and never this personal. Socializing with other survivors is typically done in groups, and there are unwritten protocols that allow us to keep safe interpersonal distance so that no one gets too attached or depressed. When you contact someone there is usually a specific reason, like if there is a sudden mass-dying of your tiny school of fish, or if you are seeking advice about having been overcharged by an extra-planetary real estate broker. Besides, most of our spaceships are very far apart from each other, and they are not designed to travel. Some pods unfortunately got knocked around during the initial escape event and are now traveling near the speed of light perpetually. Others have latched onto the gravitational force of a moon or a planet in a foreign solar system, revolving regularly around another mass.

03:45am: “Hey, it looks like you are only fifty million kilometers away from me. Wow.”

I have no idea who is messaging me at this hour. All survivors share one singular time zone at this point, so there are no excuses to intrude anyone right now. But, it’s true: fifty million kilometers is comparable to what Earth was to Mars. No one is that close to anyone anymore. Last time I thought I was in some proximity with another human, I had to measure my distance almost in light years. How there is another human this close I do not know, but it’s reassuring to know someone is out there. Honestly, I don’t even know if I want to reply. I like singing in my pillow room to my team of tilapia by myself just fine. Plus, if I get distracted from the management of my investment trust account, it could be days or weeks before I collect my next dividend. That said, I think I do miss the presence of other humans. It is very nice to hear from this person.

03:48am: “Wanna chill?”

I once again stare at the reflection of my own face against the total darkness out there, being half-awake at this hour. Fleeting meteors slash against the countless stars and planets like an abstract painting I once saw in a museum on earth. 03:48am? Timekeeping is primarily done for medical reasons at this point, and I should try to go back to sleep. From the corner of my eyes I can see the tiny school of tilapia swimming back and forth. Like a flying fleet of disco balls, the fish scales glitter back at me. I am a monster. I eat my only companions. Perhaps it isn’t such a bad idea to try and meet a different companion that I can talk to in real life. Perhaps it’s time I experienced a social connection.

The stability of my status quo has made me forget the idea of time, joy, and purpose. The synchronized interfacing of my human body with this space-envelope that allows me to breathe air inside this vacuum is quite a miracle, but my relationship with my clock, my routine is the true marvel. The cylinder that keeps me alive is not just the cross-section of the fuselage, but the idea of a twenty-four-hour cycle that I exported with me from Earth. The constant maintenance of this oversized life-support metal jacket keeping myself alive is run on the unexpirable software of my unbreakable daily routine. Unlike on earth where every few years people not only reconstruct their exosuits—building or rebuilding buildings, designing or re-planing cities—but also the update their version of humanity—re-learning how to live together—neither the software nor the hardware up here can afford change. Here there is no maelstrom, no anguish, no social contradiction. I simply pass time regularly.

03:55am: “My place? There’s a gas giant nearby, really pretty!”

But maybe I want change. I’ve been staring at the same constellations in every direction since I don’t know when. A gas giant sounds nice. I hope it resembles Jupitar or Saturn—the swirl, the hexagon, the ring. Actually, anything. I would love to see something new. Even the moons around the gas giants back in our own solar system were interesting. I also wonder if other people are as well-organized as I am. It would be great to learn about someone else’s lifestyle.

03:58am: “My tilapia stock is teeming and thriving. Would you like to diversify your gene pool?”

This is either the strangest proposition I have ever received or a real conversation about pisciculture. A healthier fish stock in my aquarium? Ok. Fine. I’m sold. Send me the coordinates.

Jimenez Lai, Spaceship Hour, 2021.

A Flapping Cyborg

I figured if I just let out a little wisp of air, like releasing the valve of a pressure-cooker, I might be able to set my pod in motion. This small amount of air should create a momentum to push my spacecraft along a new vector, allowing me to eventually accelerate on a trajectory towards this gas giant. I should be able to reach my terminal velocity in about two months and arrive in another five. I can even use the gravity of the gas giant to slingshot myself back towards the coordinate and decelerate by mirroring the air-wisp strategy in the opposite direction. The control panel of the heating-cooling unit is lodged inside one of the caps of the cylinder. I can access the buffer vestibule to let out some air.

The moment I dialed the nozzle on the air supply, I had the air sucked out of my lungs. The vacuum of outer space rapidly forced a much higher volume of air out of the pod than I anticipated. Like a round of bullets fired by a Gatling gun, the tufting buttons flew out of the pillows towards me, loosening the room into more of a flaccid pile of cloth, with batting flapping in the gusting air. The structural members of the storage rooms bent out too, pulling off the nuts and bolts and tearing off the cladding fabric. Some of the plants outside of the greenhouse withered immediately, and the greenhouse itself collapsed. The toilet, connected to the compost ductwork was emptied immediately, and made this struggling noise when trying to siphon out any remaining fluids left in the system. Something was caught in the air gap and produced this flatulent sound, alongside the fluttering of my fitness resistance bands. A few of the buttons ricocheted off of the aquarium and cracked the glass. I scuffled as I tried to remember the emergency protocols from the instruction manual.

As I latched off the vestibule to restore cabin pressure and stabilize temperature, the aquarium ruptured and the tank exploded. Blobs of water spewed out and floated around in the spaceship, some of which contained tilapia helplessly trapped in the globular water bubbles. Some of the unlucky fish without water suffocated promptly. The inward-facing water pipe deformed due to the sudden change in temperature and pressure and started leaking more globs of liquid. The pillow is no longer taut, and greatly expanded in volume, vastly reducing the amount of occupiable interior space. Home is now a well-shaken snow globe full of buttons, batting, fiber, nuts and bolts, microchips, farm tools, utensils, broken glass, tooth, blood, soil, feces, urine, dead leaves, dead fish, and shimmering globs of water. Like every other confetti I saw on earth, I reckon it will take some time before I can properly clean up the debris.

Jimenez Lai, Spaceship Hour, 2021.

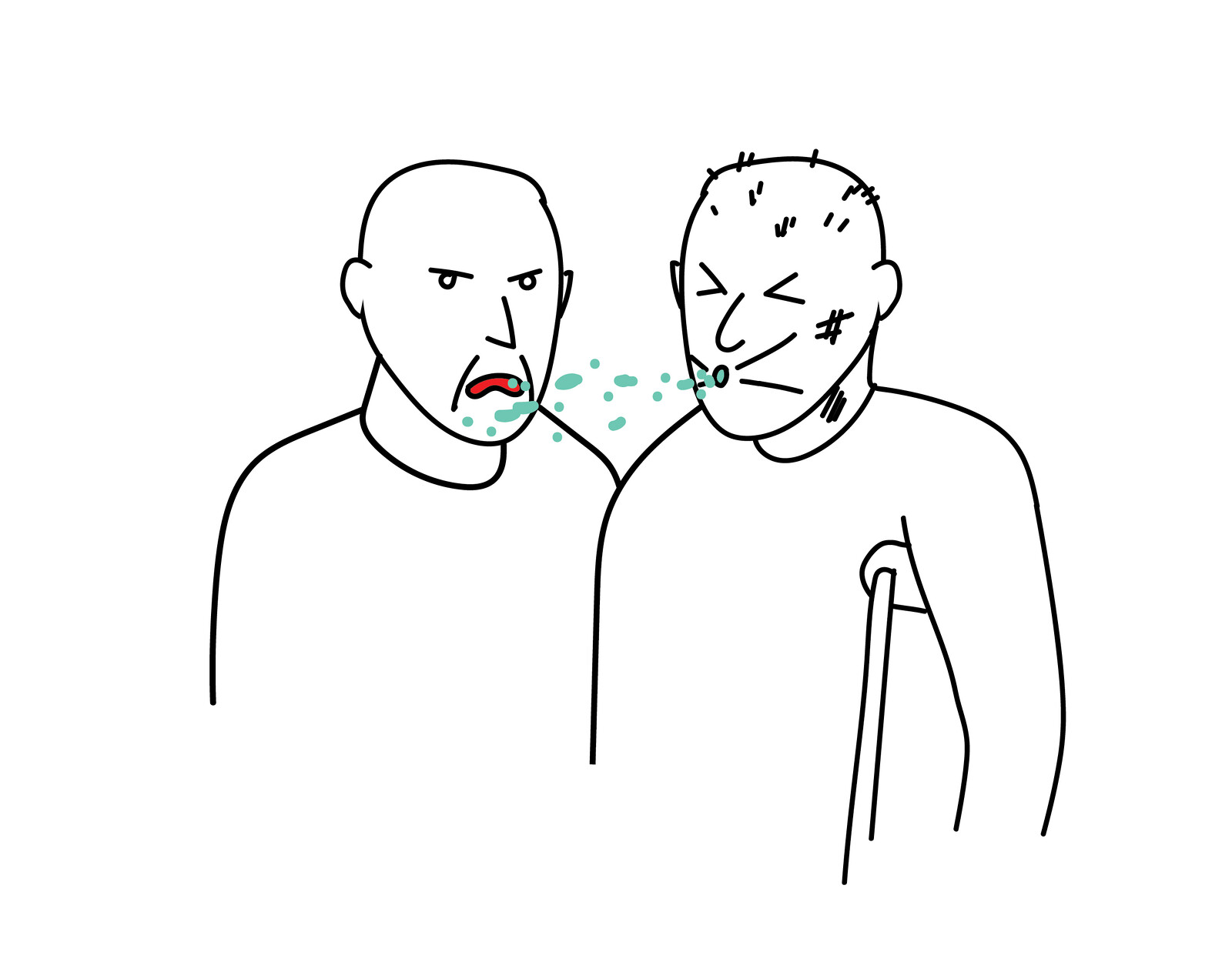

At the same time, my wristband has started sending electric shocks with a much higher intensity than I’ve been used to. I did just sign up for the highest fish-alert membership level last week. If I took the wristband off, however, the spaceship would think I was medically dead and shut off all vital functions to conserve energy. My body is badly bruised from the tufting buttons and other flying objects, my face is bloody. I can barely raise my arm; my shoulder was hit by some projectile. I think there might be a fracture on my left femur. I might have a broken ankle. I turn on my flashlight to access the medi-pack, only to remember that I used most of the gauze and surgical sutures last month for an arts-and-craft tele-party when we made stuffed animals. I also mixed most of my iodine supply in a nutrition supplement workshop some time ago. My medical supply is not in the best condition. I am lucky to be still alive.

I try to gather the disparate globs of water to form a larger and singular body. As I do this, my blood and some of the gear oil comes into contact with the clean water with the tilapia, which they now have to swim in. I try cleaning the floating water globe by picking out the contaminants, but that only worsens the situation, introducing even more debris into the blob. As I begin to tally the casualties, I count that the school of tilapia is down to five. Thirty-one fish are dead. My entire tomato patch is gone, as is the spinach colony and all of the legumes. Luckily, the onions, beets, parsnips, and potatoes survived the greenhouse implosion. I need to rethink my recipes moving forward. The nuclear reactor seems intact, despite the precarious state of the fractured control pad, flickering glitched digital numbers. I shut off the water to start the process of replacing broken pipes. The clock still seems immaculate. It looks like it’s 6am.

My pod is now accelerating and picking up velocity. I can see my injured face against the total darkness outside, now trickling with streaks of stars and planets rapidly moving behind me. I am fairly certain the trajectory towards the gas giant has the correct coordinates, but I really just need to take a moment to take my mind off my current plight. As I continue to sustain the electrocution on my arm and the throbbing pain all over my body, I am thinking about ways I might be able to preserve the dead fish for future consumption, as well as strategies that might keep the living ones alive. My eyes are closed. I am floating around. I think I need to take a nap.

Jimenez Lai, Spaceship Hour, 2021.

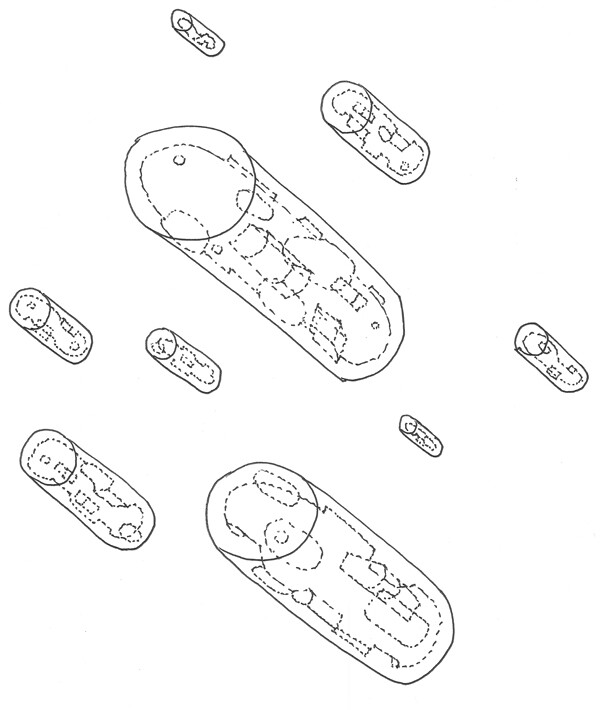

Gas Giant

How many months have gone by? Two? Ten? It’s even harder for me to assess larger volumes of time since I lost a good percentage of my plants and fish. My injuries have largely subsided, although I lost some vision in my left eye and have scars everywhere. I managed to repair most of the damages to the interior of my ship. Some of the consequences, however, are permanent. I collected all of the floating buttons and re-tufted the pillow room as much as I could, but I cannot re-shape the pillow room back to its original state. The tension of the tautness is not as tight as before, but it does help me regain some of the living spaces taken up by the batting. The five remaining tilapia are safe inside my floating water-sphere. They spawned a few offspring, which are now fingerlings. I had to reduce my daily caloric intake down to 1,500 to allow time for my farm to regrow. Luckily, I had thirty-one dead tilapia that I needed to eat as quickly as possible, which kept me nourished for a while.

I cancelled my fish-alert subscription so that the buzzing would stop. When I wanted to end the transaction, the conversation turned into a two-hour long attempt to persuade me to keep paying for my account but with a lower wattage. I thought about joining some of the post-traumatic-event support groups on some of the teleconferencing channels, but I did not feel comfortable showing my face after my ordeal. Due to the injury to myself and my ship, I was unable to maintain the same degree of upkeep, and as a result, I have received a cut to my salary. I sent a few direct messages to my late-night pen pal to explain my situation. At first, we chatted a lot. It was great to talk to someone about losing almost all of your tilapia stock. But recently, we haven’t been talking to each other so much. The unwritten protocols about attachment and depression did not consider resentment or bitterness. We have never even met, but I worry we’ve already fallen out.

I wake up to the reflection of my injured face against a glowing red-hot gas giant. No swirls, no hexagons, no rings. My digital pen pal dispatched a rescue receiver to catch me. I traveled fifty million kilometers to meet another human, and I finally arrived. I watched as our pods docked with one another slowly and my vestibule door opened for the first time since the disaster. I was elated that my journey is finally at a close, and honestly looking forward to meeting this other person. I am no longer just a perfect cyborg. I must have travelled this far because I longed for some change, some social contact after all. I chose to be a broken machine so I can be more human.

“Yeah… Do you not keep yourself organized? Looks like a mess in here.”

This is how we met for the first time. A pinched nose indicating a look of repugnance, arms crossed, eyes rolling and lips tight. We chatted briefly, and went back to our respective chambers. The vestibule door remained closed most of the time, except for the few occasions I asked for some help on my tilapia restoration project. We visited a few of the moons of the gas giant when their orbits got close, but each gathering would end in bickering by the end. For either of us to move away, one of us might have to trigger a similar misery I already experienced.

On rare days, though, we do have a good time eating together, reminiscing about life on earth, laughing about TV shows we both watched. My tilapia colony has regrown, my greenhouse is reseeded, and my spaceship is mostly back in full function. There is no longer just darkness against my reflection, but a glowing red ball. I no longer think about timekeeping solely for medical reasons, but sometimes for social reasons too.

Cascades is a collaboration between MAAT - Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology and e-flux Architecture.