I’ve been walking along this mountain belt for hours. I think I’m getting close—at least, according to the footage my drone captured yesterday. There were no pathways throughout, but I’m determined to find it.

I’m at the northwest side of Yunnan Province, “where heaven is,” my granddad used to say. He was from a village in Yunnan, but I grew up as a city girl in the East. I’ve only seen photos of what it used to look like here from his worn photo album. In these photos, the landscapes were covered by all kinds of vegetation, so dense that you could hardly see the sunlight shining through. The large variance in mountain elevations once created the most biologically and culturally diverse areas in China. But now I’m stepping on dry soil, feeling somewhat melancholic.

Some years ago, they cut down the last bit of the rainforest left in the Amazon. Nowadays you can hardly find a natural forest anywhere on Earth. Deforestation led to soil erosion and desertification, which made it almost impossible for agriculture to take place on land. Farming has completely moved indoors.

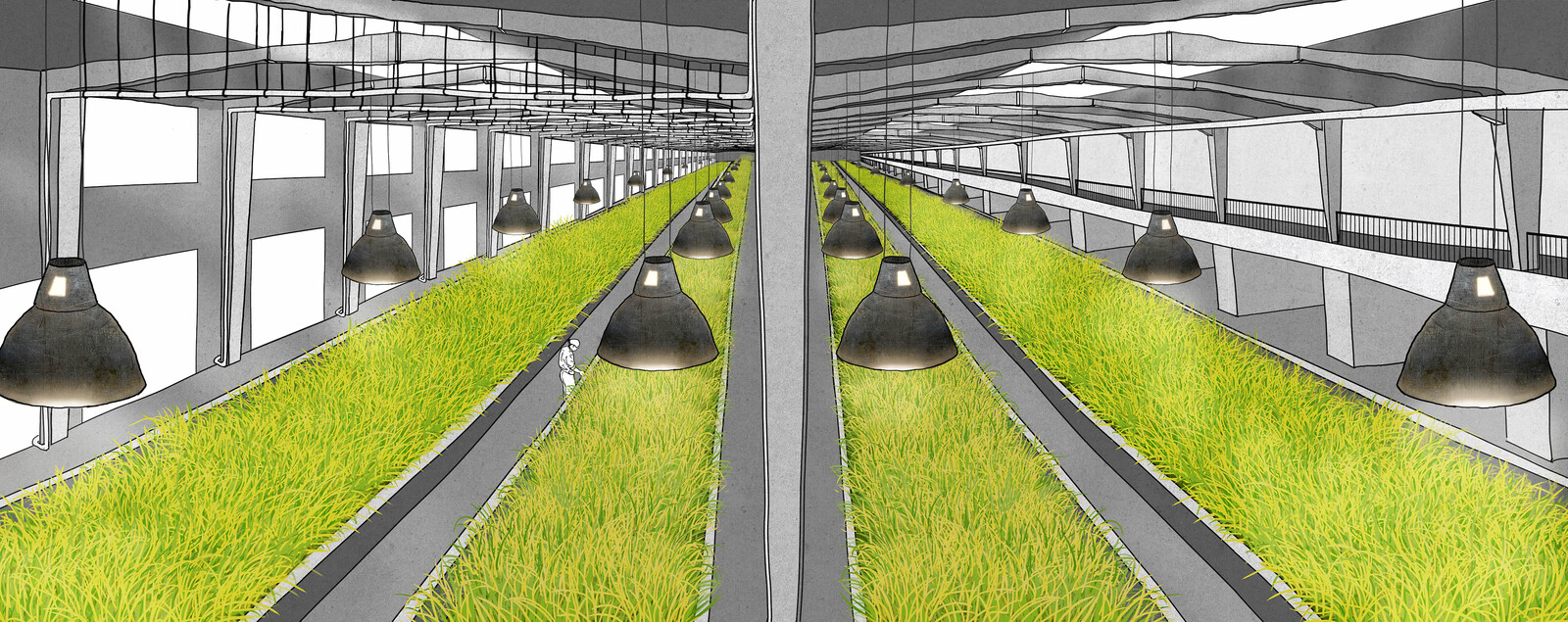

With the passing away of the boomers, as well as the ongoing decline of birth rates around the world, many architectures that were once built as a sign of surging economic progress have been left idle. Some of these abandoned structures were turned into urban plantation labs, and were given the name “infrastructure farms.” This phenomenon was especially prevalent in China, where the post-one-child-policy-society saw a sharp decrease in population, and many idle factories, schools, or even trains were converted into these semi-greenhouse, semi-laboratory spaces. The factory my grandfather worked at was in one of these “factory cities” that got turned into a giant “farm.” Although he was a farm boy since he was little, modern agriculture was too technical and complex for him to recognize.

Grandpa was from the Derung ethnic group, most of whom live in autonomous regions in north Yunnan. He was one of the two young boys from his community who made it to the cities. He worked multiple jobs while studying at night school, which is where he met my grandma. Like most Derungs, he believed in his tribe’s animist spirituality; that anything in this world has a spiritual essence, regardless of whether it is human or nonhuman, living or non-living, object or place. This created a special relationship between Derungs and nature. He loved telling me how life was when he was a boy in the village—the animals, the forest, the mushrooms, the fields… He would say things in Derung, and eventually I picked up the language.1 He would get really upset about what people have done to nature: deforestation, mining, pollution, animal extinction etc. When he used to say, “What if the spirit of the forests and animals came back and haunt us one day?” I thought he was just being paranoid and superstitious. But now, looking around this barren landscape, maybe he was right all along.

***

Industrial soil transportation wasn’t uncommon decades ago, but it became ubiquitous with the boom in indoor farming. The sheer scale of these farms enabled extreme monocultures. There were areas hundreds of acres large just for growing rice, or for potatoes, or tomatoes etc. Soilless cultivation was popular and profitable, but people became increasingly nostalgic for things that grew from soil.

In the middle of the twenty-first century, while intensively logging the natural forests such as the Amazon and Southeast Asia’s rainforests, Western developers figured out that they could make a fortune from not only the land and trees, but also the soil. Amazonian soil, with its historic fame and the rich biodiversity it once hosted, became popular around the world for growing exotic fruits and vegetables for high-end markets.

The success of Amazonian soil triggered an extraordinary trend of soil exploitation around the world, often following the clear-cutting of natural forests. Their business quickly extended into trading seeds, sometimes along with the soil, to be grown in infrastructure farms with strictly monitored artificial environments. Moreover, a handful of companies emerged as middlemen—importing soil for a cheap price, growing certain crops, generating seeds, and selling out for a much higher price to other farms.

Soil trading and transportation suddenly became one of the world’s most prosperous industries; every country wanted to be part of it. Nonetheless, most developers of the infrastructure farms were owned by developed countries, and they would make profits from the large price gap between buying cheap fertile soil from developing countries and selling the crops at scale.

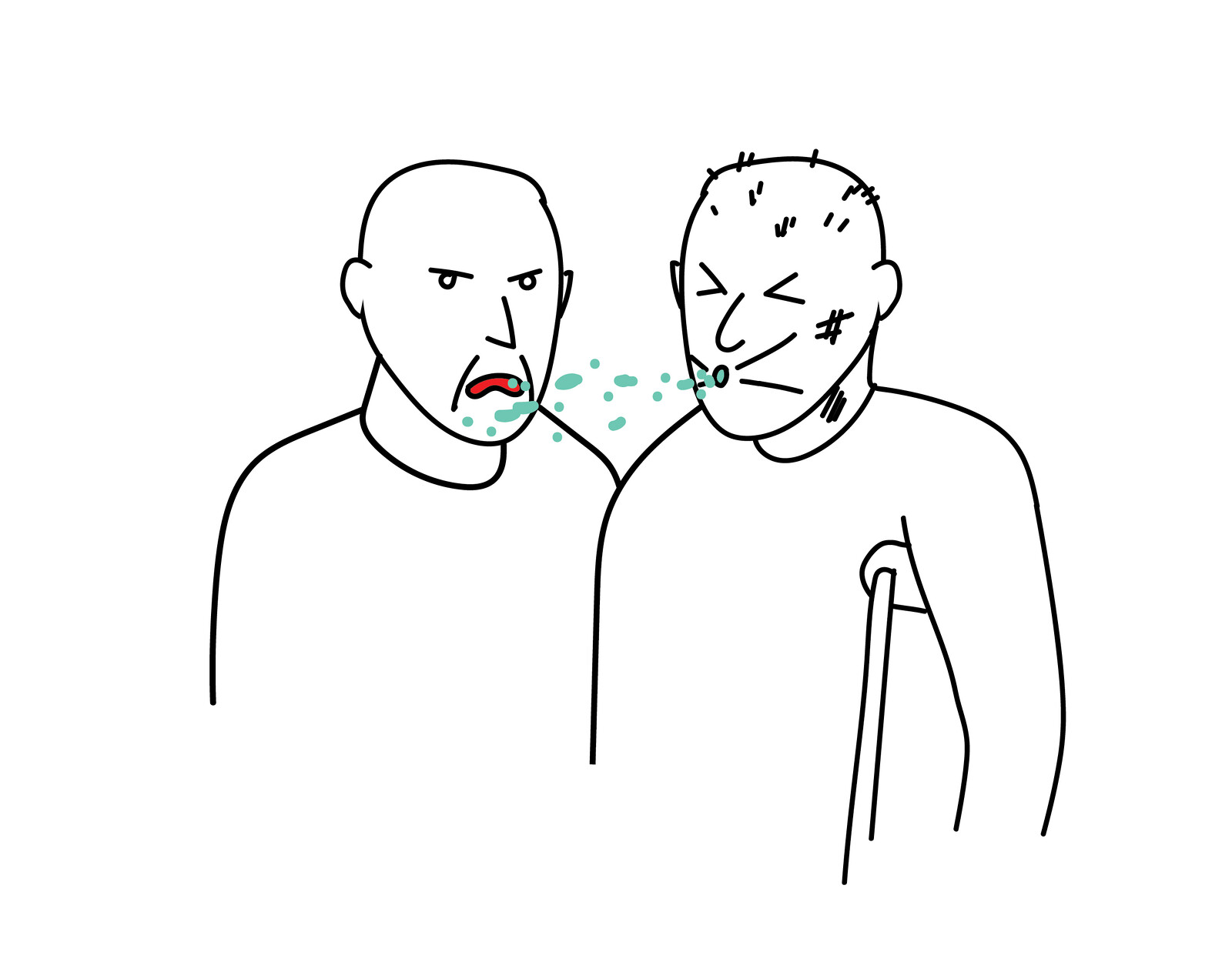

It all seemed right until it went wrong. Soil started to get mixed up during transactions, intentionally or accidentally. No one was sure exactly where, or when the so-called “super pathogen” appeared. But this bacterial pathogen hidden in the soil killed all vegetations that grew on it. The intensive (and careless) practice of mixing soil made it extremely challenging to find its origin.

We knew that this soil-borne pathogen was probably contained by its endemic location, but that either during transportation or cultivation, it was brought to new, extremely vulnerable environments. The pathogen did not only infect and kill, but also spread and evolved into variants. Initially, scientists did not understand why plants were failing so badly; they suspected that something was wrong with the program of the artificial environment. And by the time they found out about the pathogen, it was too late.

During the peak of these infrastructure farms, the majority of the industry abandoned applying pesticides so that their products would be certified organic. The sudden appearance of this “super pathogen” led to the discreet return of chemical pesticides, but they didn’t work as expected. After a short-lived decrease in the infection rate, the “super pathogen” soon came back in an evolved pesticide-resistant strain. The pesticide-permeated agriculture during the previous centuries had overloaded the soil with residues that eventually left them immune to chemical agents. Furthermore, as healthy indoor crops were made to grow in impeccably maintained, pest-less environments, they too became too fragile to survive from chemicals. Crops were dying on a tremendous scale, resulting in a global food shortage.

Despite endless efforts to eliminate the pathogen, no feasible solution was found. Panic and famine proliferated. Out of desperation, each nation began organizing their own teams to look for any possible leftover fertile lands within their territories, with the hope of experimenting with alternative agricultural techniques. Yunnan, despite its history of deforestation, was chosen as one of these sites for its once-abundant wildlife and rich biodiversity.

***

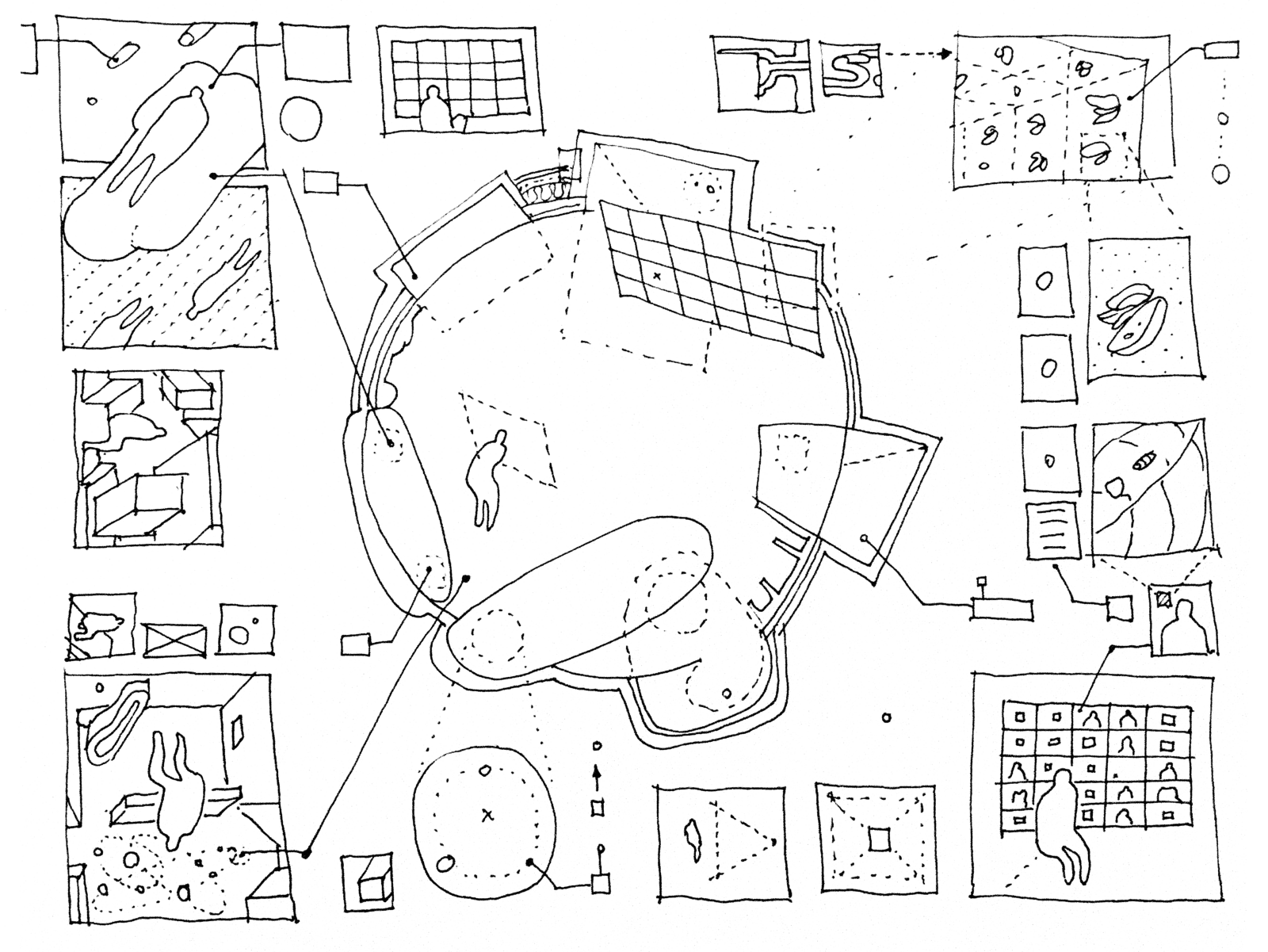

Yunnan is known to be a tough area to survey; it ranges from canyons in the west to plateaus in the east, with its mountainous terrain extending all the way up north to the Himalayas. Its famously complicated landscapes have shielded its indigenous inhabitants from invasion by the outside world throughout history.2 Although much of the area has gone through modernization, there are still patchy areas left unexplored. Without infrastructure for cars or even helicopters, no one wanted to come here.

But I volunteered. It was of course to seek hope, but there’s more to it. In Chinese, we have this old word Xun Gen (寻根), which translates as “seeking roots,” and means to look for where we come from. Grandpa was from around here, so this is where my “root” is. I had always wanted to come here and see it myself. Now I was finally here, only for a different purpose as had I originally imagined.

Unlike last century, satellite imagery has now become one of the most difficult kind of information to access. During the last upsurge of deforestation, a series of articles published by groups of NGOs and environmental activists showed comparisons of satellite images from public sources and their own drone footages taken secretly on the same land. Their differences made it evident that satellite data had been frequently manipulated by public and private investors to erase or modify their footprints. The scandal quickly attracted attention from the media who dug out more similar cases around the world, and revealed how scarred our landscapes really were.

People were shocked and furious. Under immense pressure, nations were forced to react. Some denied the accusations; some promised tougher supervision on public mapping sites; some banned all sales and ownership of unlicensed drones. But official responses only prompted more people to voice their distrust and outrage towards governments and large corporations.

Decentralized protests and strikes were organized around the world. But a difference in opinion over what they were advocating for quickly emerged among the protestors: should they demand absolute transparency and openness, or banning satellite imagery altogether to protect privacy? As the debate went on, so did deforestation. Meanwhile, the public gradually lost access to satellite and drone imagery, which eventually became state-owned.

When the pathogen was first discovered, many countries focused on discovering its origin and inventing an antidote at the expense of dealing with the effects of the global famine and the great economic recession it brought about. Funding was suspended to some of our highest-budged government agencies, including the National Space Administration. With limited technical support, then, a group of us were sent to various locations to physically carry out site surveys. We were, however, given state-owned drones to aid us in our journeys.

During the past months in Yunnan, I’ve been to most mountainous areas in the north. I let my drone take me to many places, but I enjoy exploring by foot too. Through the camera I saw a very different world than the one my grandfather had described: the rivers had dried, the mountains had degraded, the dwellings had been abandoned. I’ve been to some clusters of neo-traditional architecture mimicking vernacular ethnic styles for ecotourism, which have become ghost towns now. I’ve hardly met anyone along my path. I can’t begin to imagine how tough life must have been for those whose lives depended more heavily, more directly on nature since this crisis began.

But yesterday, my drone accidentally captured something that overwhelmed me with excitement. Even farther north than where I had been, in a valley within an uninterrupted mountain chain, I saw smoke. I first thought was that it must have been a wildfire, which made me nervous. But when I looked closer, I saw that the smoke was coming out of the chimney of a primitive-looking house, sitting beside small patches of light green and golden fields. I couldn’t believe my eyes. Could this be fertile land, being cultivated by someone? I had to see it for myself. After plotting a path last night, I set off first thing this morning.

***

It hasn’t been an easy journey; clearly no one has been here before. Exhausted, and after a long while, I finally arrive. Behind some scattered conifers I see this beautiful village, with crops growing in the fields, although I’m not sure what they were. Among the houses, I instantly recognize the one I saw from the aerial footage. After working up the courage, I knock on the door.

To my surprise, the door opens straightaway. Behind the door stands an old lady, her one hand holding the door handle, the other with a bowl of food in it. I am completely caught off guard and lost for words.

“Hi.” She breaks the silence, and with a warm smile says, “Please come in.”

I did not expect to be welcomed without being asked any questions, but she makes me feel at ease. She speaks in a language that sounded very similar to Derung, so I have no trouble understanding her.

“Thank you.” I follow her and enter the house. It has a simple but spacious layout: there is a square table with a stove in the middle, above which is a pipe extending up to the roof. She leads me to sit on the bench with her at the table.

“Welcome, young girl! Please have a cup of tea.” She picks up the teapot that was heating on the stove and serves me butter tea. “I haven’t had a guest for a long time! You speak our language, but you don’t seem to be from around here. What brought you here?”

I tell her that I grew up in the east, but I was the granddaughter of a Derung man. I find it hard to begin to explain my reason for being here, so I ask her instead: “Are you aware of what’s going on in the world right now?”

“The… world?” She shakes her head. “I’ve lived here all my life. I’ve never seen the ‘world.’ Our existence has always been a secret.” She pauses for a moment. “We are the Bador people. Just like Derung, we were part of the Qiang ethnic group before being divided into different subgroups. To protect our people from seemingly perpetual wars, our ancestors isolated themselves after escaping to this hidden valley. We have kept our culture and traditions, remaining nomadic and self-governed ever since. We were not completely detached from the outside, though. We knew something was going wrong. The birds stopped singing, the monkeys stopped visiting, and the abnormal weather had made it hard for crops to grow. Our lives became more difficult than before. Now I’m the last one left.”

Her words leave me speechless. It seems cruel at this moment to tell her the disastrous situation the rest of us humans have caused for ourselves, as well as my intention of being here. She seems to have figured out my frustration. “For whatever reasons you’re here, you’re my guest. Come, let me show you around.”

The woman seems to be around eighty years old. Her back is slightly arched, but her footsteps are fast and stable. She points at the crops and tells me they are Tibetan barley and potatoes, which have been here ever since she could first remember. They apparently used to have dozens of yaks, lambs, and other herding animals, but now there is only one yak left, who has become her only friend. They used to graze over the mountains to other territories. Nomadic groups, despite being from different communities, acquiesced in cross-territory herding and foraging; it was their unspoken agreement to keep peace. During the past decades of destruction, however, ethnic communities and wild animals started to move away or diminish. The secrecy of the Badors protected them from being discovered, exploited, and vanished, but this also meant they had to strictly remain in their own territory and never leave. “Everything that’s given to us by nature was a gift. I’m the last remaining guardian of my land.” She says to me softly but firmly.

I am stunned. This lady standing in front of me has devoted her whole life to guard her land, which is probably one of the last pieces of fertile land on Earth. How was it that this primitive and simple way of living has survived all this time? Were we too greedy, or were we just too arrogant to admit that we were not as powerful as we believed ourselves to be? The thought of my intention of being here suddenly consumes me with guilt. What would happen to this beautiful place if people found out about it, through me? I can’t begin to imagine, and I don’t want to. So many homes have been destroyed and erased, including my grandpa’s. I don’t want her to lose hers too.

***

The next morning, I bid farewell. As much as I would like to stay longer, I know that the only way to keep this place a secret would be to safely return to my team. Only when I hug her goodbye, I realize I never asked her name, and she never asked mine. But it doesn’t matter to me. I want to be an anonymous guardian of this land too, by keeping it a secret.

Derung is a language that belongs to the Sino-Tibetan language family.

James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009).

Cascades is a collaboration between MAAT - Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology and e-flux Architecture.