“This can’t be architecture…” Kali wrote on his yellow layout paper while gripping his clutch pencil. He sat obtuse against his chair looking at the ceiling moving his eyes across the steel GI conduit pipes that snaked over the studio room, feeding the gallery swivel lights with geothermal power. “Ehh! Kali, what’s up now?” Mumbi asked, as she peered over her monitor screen tilting her head to glance at him. “Ok Mumbi, angalia,” he said in Swahili, or “look here,” to get her attention as he lunged forward. “I know we signed to be the ‘enviable’ architects of record here to deliver the Origin Museum, and yes, it is a dream brief and our partners are insanely talented, but in all honestly it seems to mean nothing when you consider the intended or unintended disconnection of our lead shapeshifting architects with what is really happening here on the ground, in our so called cradle of mankind.”

He continued: “No amount of dezeening, archiloving, archdailying, or pinteresting of the latest African works by Francis Kere, Mariam Kamara, or Kunle Adeyemi, nor the so-called ‘project immersion workshops with the locals,’ will equip them to embed this project in the culture. It just feels like they’re exhuming some opaque colonial justification to generate an architecture, postulated from the global north to attract foreign tourist footfall to hear the story of humanity’s emergence from Africa. So, in the end, we can only just sit and enjoy the show, as we, the proverbial ‘architects of record’ get paid to plant this intricately beautiful aberration of our culture onto the land.”

“Eh kijana tulia basi, si twende lunch tu chambue hi mambo, ndio isikusumbue saana,” (“Eh young man, take it easy, let’s go for lunch and hash this out, so that it doesn’t bother you too much,”) Mumbi said. They left the bureau to a roadside stall on Lenana road in Kilimani, Nairobi. “Wakia Cucu,” Mumbi greeted in her mother tongue Kikuyu; a respectful greeting to the patron lady, who was old enough to be her grandmother. Joyce replied to Mumbi, “ehh mutugori wakwa, uhanatya?” “Yes my boss, how are you?” “Di mwega Shosho, tu rehere kawaida please.” “Yes, I’m fine, grandmother, please bring us the usual.” They soon got their plates and were piecing through their kale with beef stew and rice on bright yellow and purple Chinese plastic plates. They ate under the short-statured timber and plastic canopy in silence, save for some small talk about how chewy the beef was, before getting into the meat of the conversation.

“Kali, do you remember the late Binyavanga Wainaina’s piece about ‘How to Write About Africa?’” Mumbi said.1 “Well,” she continued, “I really think we’re dealing with the same challenge here, except we are looking at ‘How to create architecture in Africa.’ Let me see if I can tap into my inner Wainaina’s piercing satirical prose,” as she winked at Kali:

Always use the words “Indigenous,” “tropical,” or “African” in your broad postulations about architecture and its production on the continent of Africa. But when insisted upon, substantively skim the surface in your references about the communities and cultures you are dealing with, referring of course to “The culture,” “Natural materials,” “The climate,” “Social norms,” and not forgetting the “objects”—either manmade or not—that seem to have all, in equal measure, given shape (but never form) to your brave new architecture. Remember to speak of how the buildings emerged through a sensitive response to this unique sun kissed earth, where barefoot children play around their African mothers or aunts. Whatever characters and rugged artistic impressions you conjure up in your story to suit your international viewership, do not forget your as-built photos of a truly African product. Always remember that this need not be explicitly stated as such, but more intellectually implied. After all, you should not come across as neocolonial in your so-called Ingenious readings of a refreshing neo-regionalism in the way you practice architecture in Africa.

For formality sake, always remember to choose your African architect of record wisely. It should always appear that they are heard but never listened to, especially when they ramble on about a deeper immersion in the cultural positioning of the architecture in question. “Their” insistence on words about “identity,” “meaning,” “experience,” “belonging,” “spirituality,” and—God forbid—”God,” should be relegated to the archives for when there is enough time to ponder over these contextual niceties that would otherwise frustrate a speedy reproduction of your praxis—full stop!—towards your Pritzker prize stardom. Always avoid being entangled by their wild under-evolved thoughts that would otherwise corrupt your project’s deeply “democratic” design workshop formation.

Your architecture should conjure up the profound in a way that it can be seen by the architectural elite, but seldom by the locals, whom you can speak about in your expatriate social circles, saying: “they struggle to appreciate the often-subjective nature of architecture that should really, at the end of the day, have a universally neutral reading.” Remember to shun the over-refined and pristine logic of the land. Instead, embrace the jagged and near mammalian emergence of your work from the African soil, where earthen blocks, rammed earth, thatched roofs, and courtyard spaces are composed with the reductionist tendencies of the international modernist style. Do this until the African soul of architecture is sucked out and replaced with yours.

Kali looked wide-eyed at Mumbi, his jaw dropped, toothpick balancing from the side of his mouth. “You’re mad, Mumbi,” Kali said. “When do you come up with these thoughts?” “I don’t know Kali, Wainaina’s words were just fresh in my mind, I guess.” “Thanks, Mumbi for that, I think you just gave me a risky idea for the Origin Museum.” “Sawa Kali [any time]; I’m happy to have helped. You better run those wild thoughts through our baraza [design] session, lest you get us fired from the job!” Kali laughed with a squint as he imagined how plausible that was. “Okay, lunch is over,” Mumbi said. “Let’s get back to the cave.”

Interlude: Reading the Return

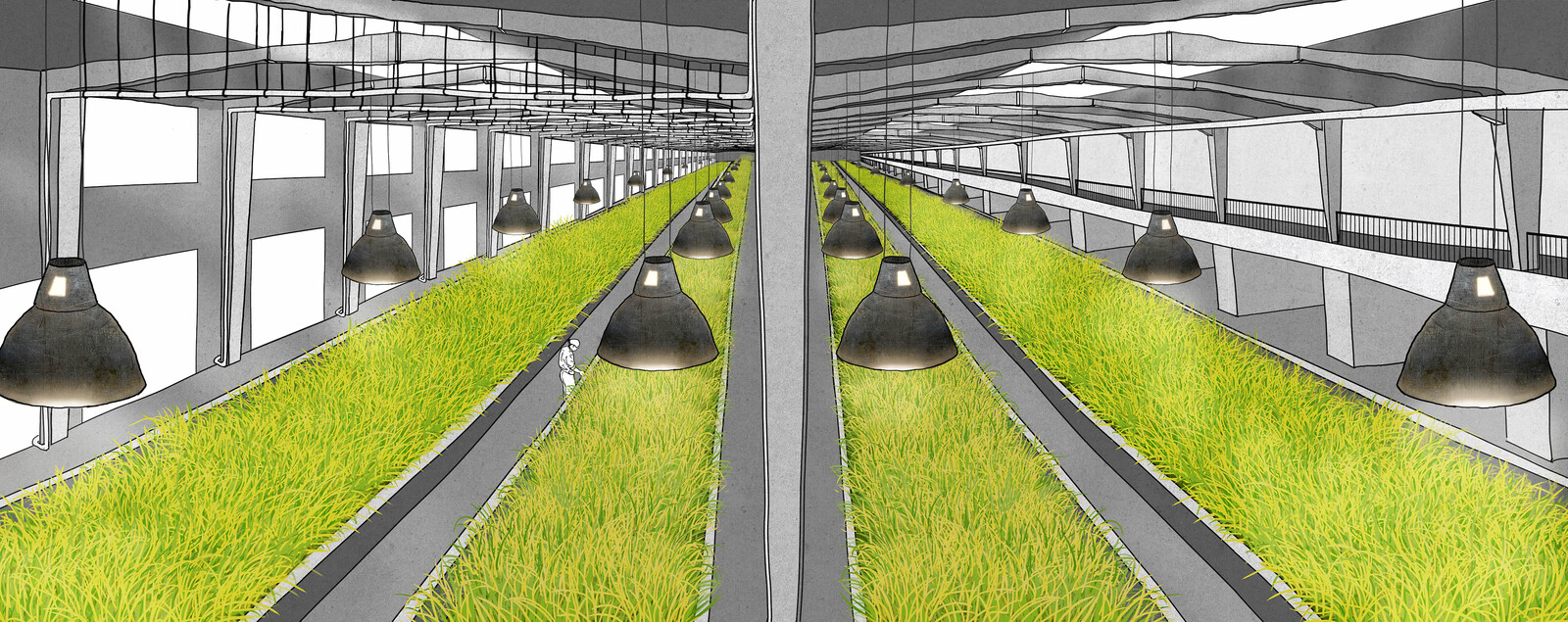

Martin Heidegger said that we only begin to understand technology when we cease to notice it. It can also be said that we only begin to understand architecture when we cease to notice it. Architecture has always existed, ever since the birth of the Earth four and a half billion years ago. Even further: to when vast masses of hot gas and matter rammed through space and time, pulled in by gravitational forces, framing spaces and cavities—caves—that eventually settled over millennia. It was through the movement of rocky masses around the endless number of suns that tectonic shifts within planets of rock-melting lava flows afforded the formation of spaces of shelter for living things to thrive. All humans—from our furthest distant Hominin relatives—the Sahelanthropus tchadensis—almost eight million years ago to our very own quarter-million-year-old Homo sapiens—share this architectural heritage. From civilization’s oral and recorded histories of religious revelations, to philosophical metaphors and narratives, and as a surface to embed our cultural thoughts and values, caves have formed an intrinsic part of our past, present, and soon-to-be future.

Our return back into the cave is coupled with our continuous fight against colonization. This journey was, and still is an ontological, epistemological, and architectural endeavor. Kenya’s vast network of caves along the Great Rift Valley cannot be disentangled from its understanding as the cradle of humankind. It’s also within these spaces that Mau Mau freedom fighters fought for independence and self-rule, reimagining and redefining the African and indeed, Homo sapiens state of the future.

The Anti-Museum Project

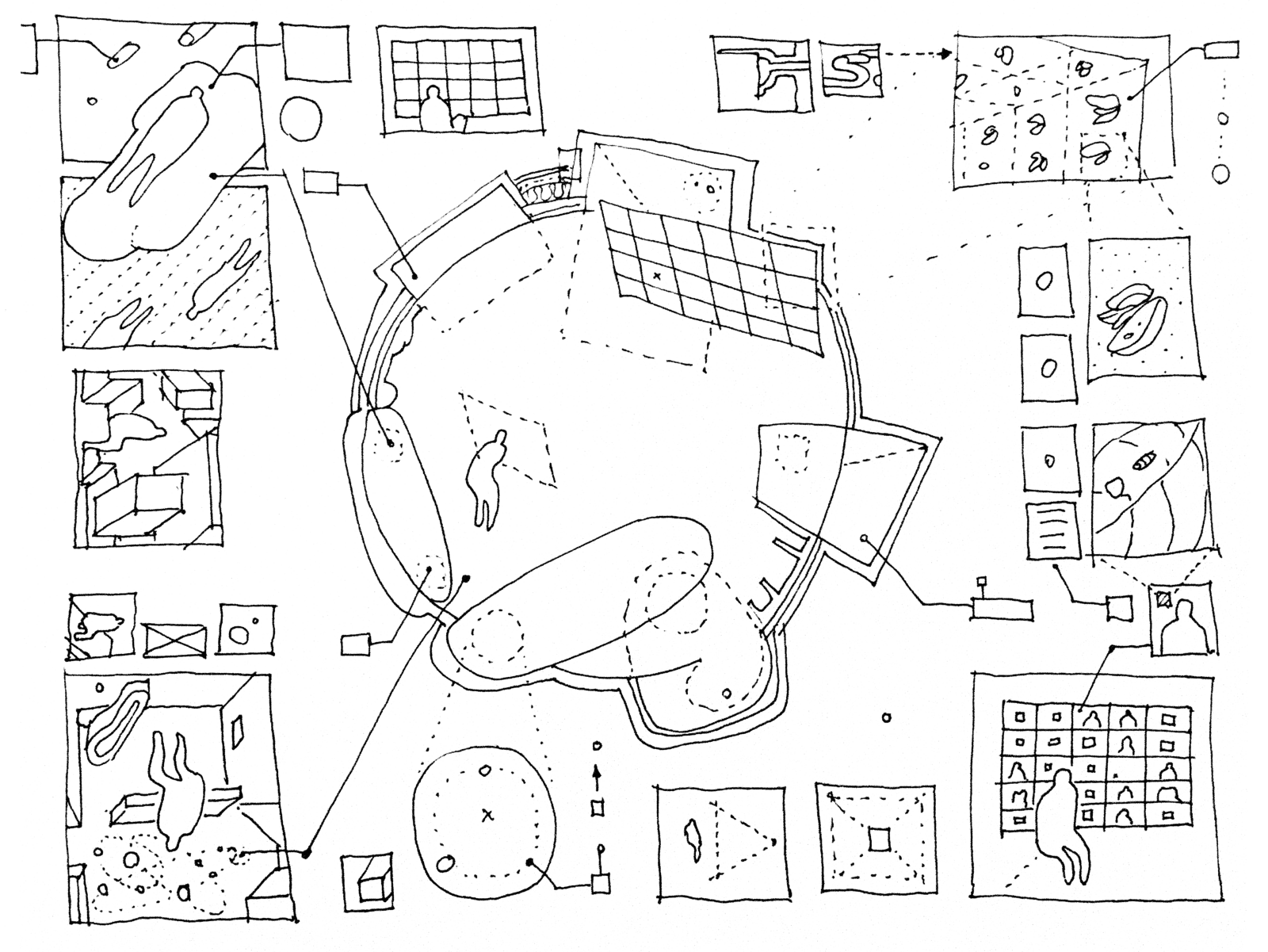

Kali took a deep breath while looking at the local team, the foreign architects, and the client, who all sat anxiously after being called for an urgent design meeting. He turned on the screen to present his “wild thoughts,” as Mumbi called them, in a few images. He said:

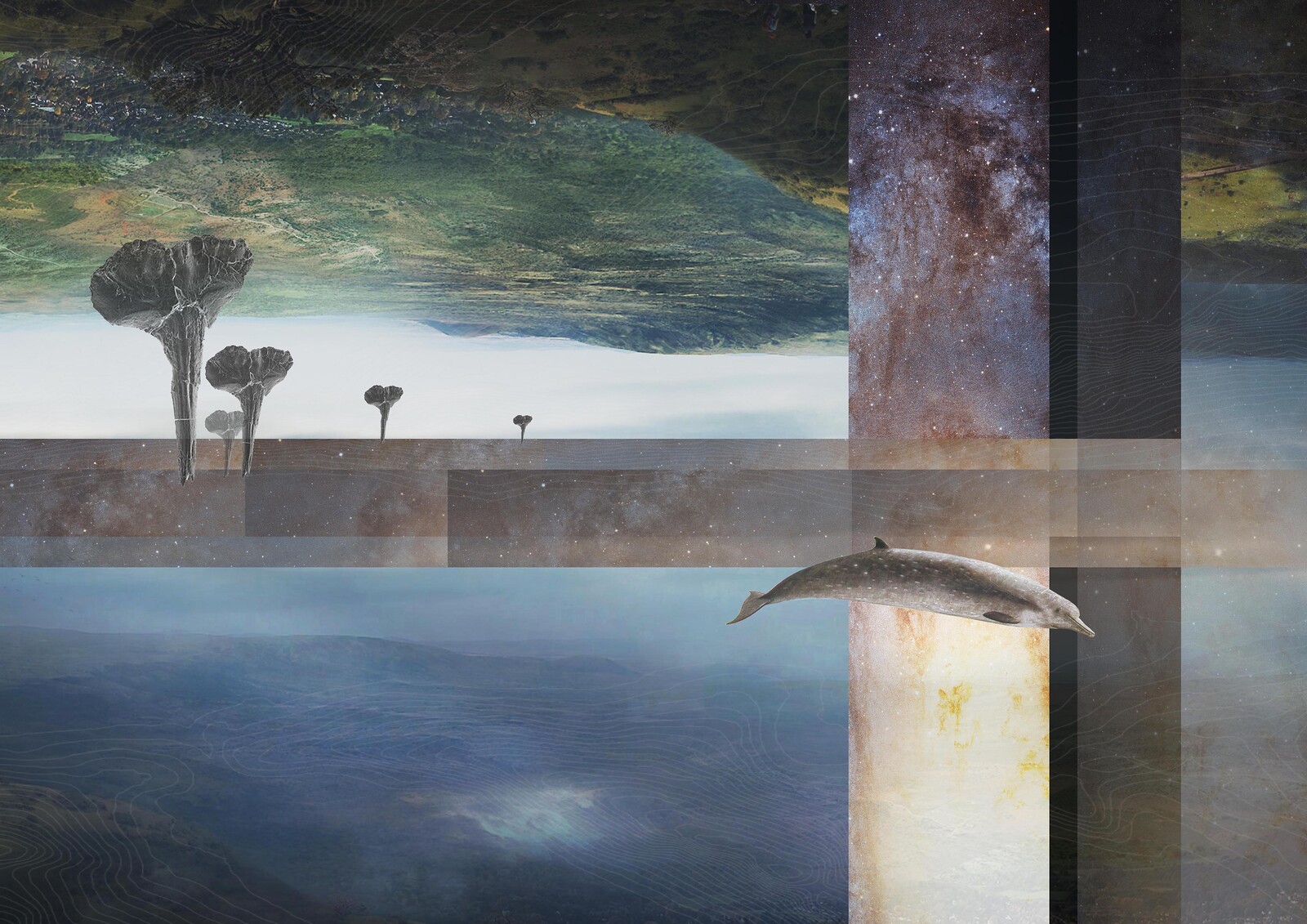

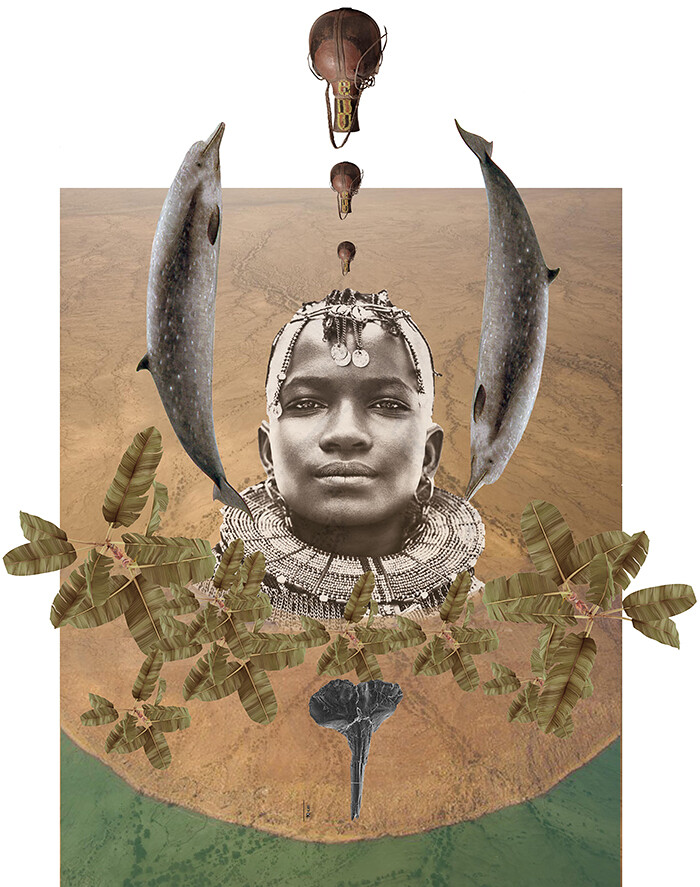

the real museum project resided in the space between the mind and spirit of the one-and-a-half-million-year-old Homo erectus Turkana Boy and that of the Homo sapiens Turkana Boy of today. Both are inextricably linked. After all, the Turkana people of today, or as they call themselves, ‘Ngiriturkana,’ meaning ‘people of the cave,’ have a shared architectural heritage. The next two images are phantasmagorical curations of present-day archeology. You can see ancient vestiges of a beaked whale fossil that was unearthed in the arid Turkana lands, miles away from the Indian Ocean. We place these whales in an atmospheric stasis over a vast territory that was once filed with sea water, and where the sublime mythical woman Nayece of the Turkana sets her eyes across the mirrored harmony of the Great Rift Valley.

The expressions in the room were an equal mixture debilitating fear and exhilaration. Kali continued by quoting John Lamphear:

Turkana traditions suggest that their society had not just one, monolithic “origin,” but rather what might be seen as a whole series of them. Highly dramatic and memorable tales of genesis provide vivid idioms of socio-political identity and also contain fundamental cosmological messages. But they also correspond to important stages of change in the development of the Turkana community, and, as such, they (together with less “formal” traditions associated with them) provide vital historical information. The factors which combined to enable the Turkana to carry out their vast and rapid territorial expansion are identified.2

Kali glanced over the audience and calmly said “I am happy to take your questions.” It was clear that the local team had been tipped off about Kali’s presentation during an internal baraza meeting. But like a young lion, left to finish the kill, Kali only had a few side smiles and winks of reassurance from the team to take the heat that was about to ensue.

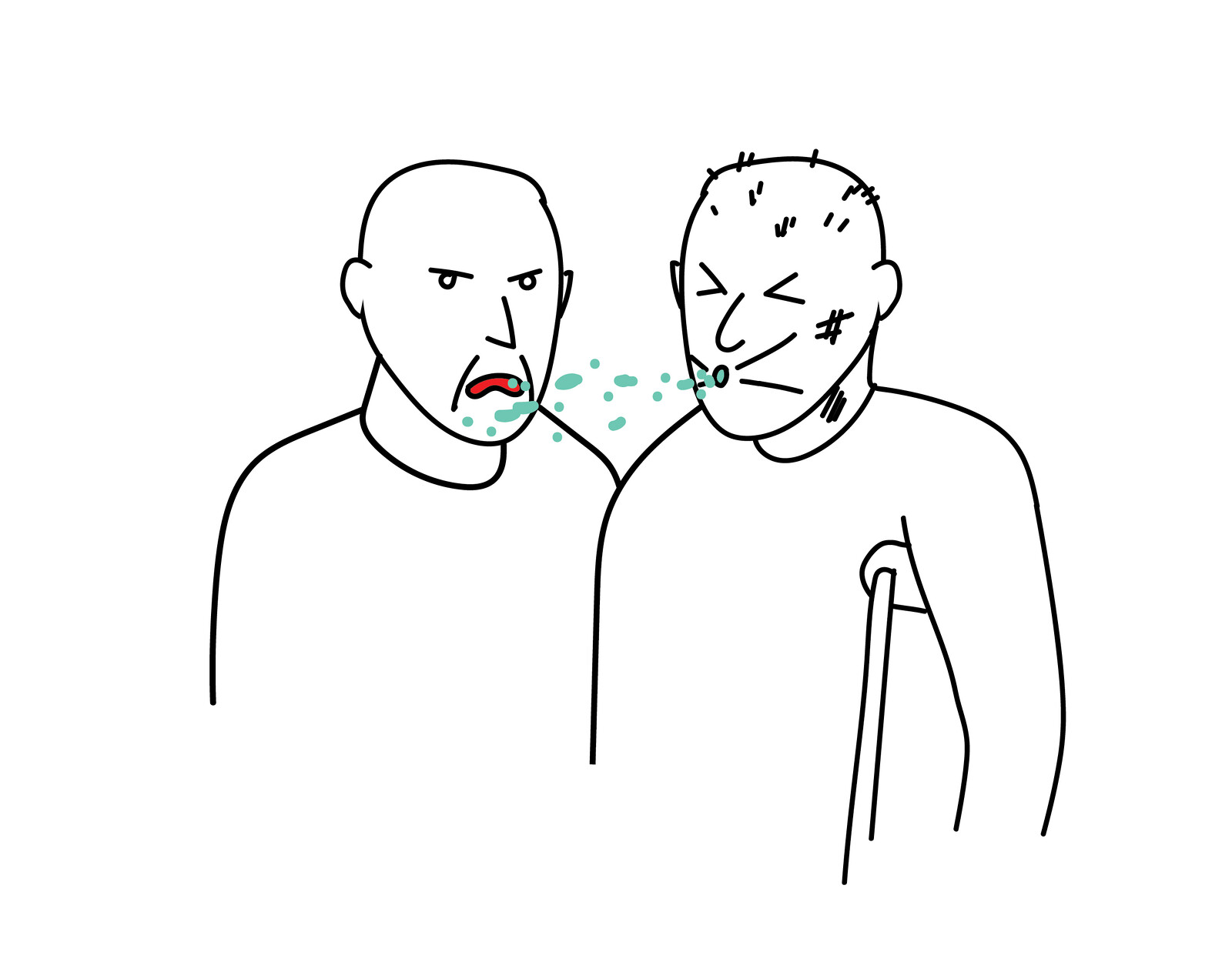

The patriarch client looked incensed as he squinted at the screen, his face turning a pale tomato red. Sensing an impending outburst, the foreign architect, who had decades of experience in defusing such situations, spoke abruptly. “Brilliant,” he said out loud, as his voice echoed. This left the client both wide eyed and jaw dropped. With confidence, the foreign architect continued: “This unique cultural reading of the Turkana people and their story of the origin needs to form part of the museum exhibition. There should be a room dedicated to this narrative about the Turkana people’s interpretation of the origin.” He continued, confidently, “We could even substitute or combine the visitor shop with this section just as they leave the museum. Your artwork could even feature on some merchandise.” All Kali could do was glance at Mumbi, as she raised her eyebrows prophetically at him.

Binyavanga Wainaina, “How to Write About Africa,” Granta 92, May 2, 2019, ➝.

John Lamphear, “The People of the Grey Bull: The Origin and Expansion of the Turkana,” The Journal of African History 29, no. 1 (1988): 27–39.

Cascades is a collaboration between MAAT - Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology and e-flux Architecture.